Executive Summary

Since the summer of 2019, protests have become a fixture across Hadramawt in reaction to the poor provision of electricity. Although the governorate is far from the frontlines and home to most of the country’s oil reserves, it has not escaped destabilizing aspects of the conflict, including the erosion of the rule of law and the emergence of war profiteering.

In the face of growing electricity demand, Hadramawt’s local authority has commissioned the construction of new power plants and the repair of existing ones, and become increasingly reliant on electricity purchase agreements with private companies. However, the lack of transparency or oversight of these deals, in violation of the competitive bidding requirements of national tender regulations, benefits a select group of actors while providing negligible improvement to the broader electricity crisis. In addition, the use of expensive diesel to fuel most of Hadramawt’s power plants increases the cost of electricity for both the government and consumers, enriching the well-connected political and business actors involved in procurement. Powerful actors involved in such deals have avoided accountability and continue to misuse public funds earmarked for electricity production. The government-aligned Parliament highlighted many of these issues in a recent fact-finding report that investigated corruption in the oil, electricity, communications, and financial sectors. Meanwhile, about 45 percent of Hadrami residents do not pay their power bills, which feeds a vicious cycle in which demand for more electricity increases in the absence of the necessary revenues and investment to meet it.

Adhering to tender regulations in public contracting would ameliorate many of the problems plaguing Hadramawt’s electricity sector. To address the problems, the policy brief recommends four courses of action: investigate illegal and corrupt contracting practices; build the capacity of local government agencies sidelined during the war; encourage community participation to enhance transparency and accountability; and roll out a governorate-level electronic database for public contracts.

The investigation of potentially illegal and corrupt contracts must involve the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, as well as the local authorities in Hadramawt, and relevant oversight bodies including the Central Organization for Control and Auditing (COCA), the Supreme National Authority for Combating Corruption (SNACC), and the High Authority for Tender Control (HATC). Investigations should identify contracts (past and present) that violate key provisions of the tenders law; namely, that contracts must be awarded through a public and competitive bidding process. Contracts found in violation of the tenders law should be referred to the attorney general’s office and specialized courts. To overcome failures in past investigations, COCA, SNACC, and HATC should be reorganized with an eye toward reactivating their oversight roles. Coordination between the anti-corruption agencies and the judiciary should be enhanced, and the judiciary should be insulated from interference from the executive authority. Yemen’s national strategy to combat corruption should also be updated and strengthened by incorporating best practices in investigation, law enforcement, and asset recovery.

To build the capacity of local authorities involved in public contracting, training courses should be conducted on rules of professional conduct, ethical guidelines, and accountability, with an emphasis on adhering to regulations of the tenders law.

Transparency and accountability in the electricity sector can be enhanced through increased engagement of local communities in the public contracting process. Local authorities, anti-corruption agencies, and civil society groups can accomplish this by organizing public consultations at which citizens can air grievances and address transparency, oversight, and other issues affecting the electricity sector. Avenues for anonymous participation should be made available to encourage broader participation from those who may be concerned about speaking out publicly. Prioritizing fair and transparent contracts, rather than potentially corrupt quick fixes to appease short-term public dissatisfaction, would help build public confidence in local authorities.

Digitizing the public contracting process at the governorate level would also help promote transparency by making information available to the public, potential bidders, and other relevant stakeholders. An open, online bidding process would make it more difficult for corrupt actors to negotiate secretive contracts, and could help reduce costs in the cash-strapped electricity sector by making the contracting cycle more efficient.

The Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen (SDRPY) recently announced US$1.2 billion in investments in Hadramawt, including the construction of a gas-oil separation and processing facility and a 100-megawatt (MW) power plant in Seyoun. These investments could serve as test cases to incorporate this policy brief’s recommendations and address the complaints of protesters.

Introduction

Hadramawt is the largest governorate in Yemen, constituting more than one-third of the total area of the country and having one of its longest coastlines.[1] It is part of the Yemeni government’s so-called “triangle of power,”[2] and together with neighboring Marib and Shabwa governorates contains all of the country’s oil and gas production. In April 2015, Hadramawt’s capital Mukalla city fell under the control of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). One year later, forces from the 2nd Military Region in Coastal Hadramawt, with the support of the UAE, expelled the AQAP militants and regained control of Mukalla and surrounding areas. This marked the only period of frontline fighting in Hadramawt during the war.

In 2017, Hadramawt’s local authority signed an agreement with the central government to retain 20 percent of oil revenues generated in the governorate for local development.[3] However, despite the availability of abundant natural resources and associated revenue streams, Hadramawt’s provision of electricity has failed to meet the growing demands of the populace, which have been increasingly expressed through street protests during summer months when high temperatures lead to higher electricity demand.[4]

In response to these public demonstrations, which have gained momentum since 2019, the local authority has pursued deals to procure new power plants, maintain and repair old ones, and expand power supply through purchase agreements with private electricity providers. However, many of these multi-million dollar deals, often negotiated in secret, violate the regulations governing public tenders while enriching well-connected politicians and business leaders and failing to improve electricity provision in Hadramawt.

This policy brief provides an overview of Hadramawt’s electricity industry and highlights the proliferation of illegal contracts and the corrupt practices associated with the sector in recent years. It then lays out the legal framework governing public contracts in Yemen before exploring efforts to combat corruption in the electricity sector.

Methodology

This policy brief undertook a desk review of literature on contracting policies in the governorate and anti-corruption legislation in order to better understand the shortcomings of the electricity sector in Hadramawt. Structured interviews were also conducted with decision makers in the central government and in local institutions at the governorate level, and local residents. These interviews focused on financial resources and spending priorities, contracting processes, compliance with relevant laws and regulations (in particular, Prime Minister’s Resolution No. 53 of 2009 of the Executive Regulations of Law No. 23 of 2007 Concerning Tenders, Auctions, and Government Storehouses);[5] and levels of public satisfaction with electricity provision in Hadramawt. The decision to focus on the electricity sector in this policy brief was informed by meetings of the Hadramawt Strategic Thinking Group, a platform that seeks to achieve a greater understanding of local dynamics and propose solutions to address the core needs of residents of the governorate.

An informed consent process was followed, and interview practices followed professional ethics guidelines. Due to the sensitive nature of issues related to corruption and poor governance discussed during interviews, considerations were made to ensure the safety of interview participants. Study participants came from a range of positions and backgrounds, including community leaders, decision makers in the central and local government, and civil society organization (CSO) representatives.

The Electricity Industry in Hadramawt

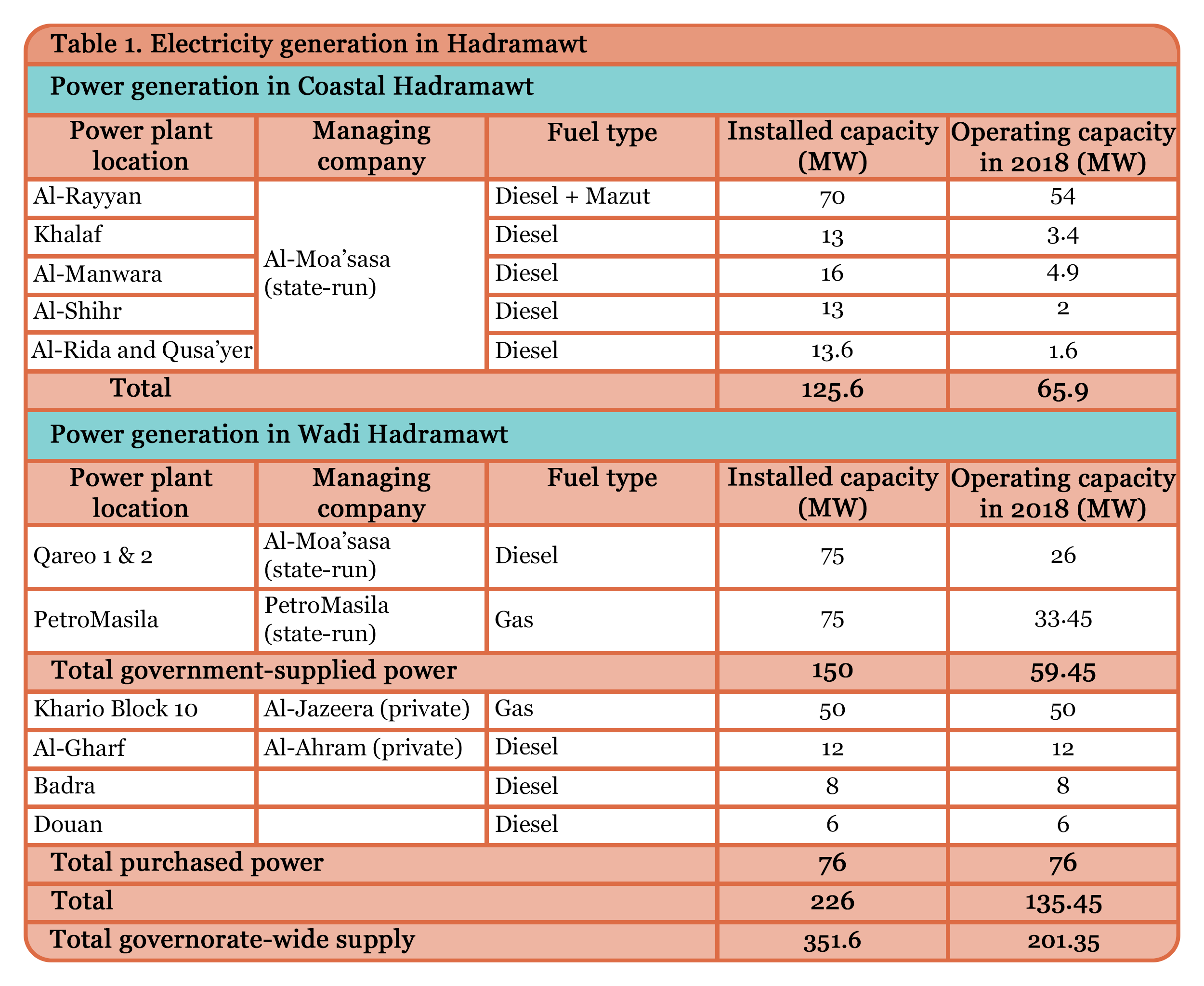

Electricity production in Hadramawt is divided into two regions: Wadi Hadramawt, the inland area of the governorate surrounded by oil fields, and Coastal Hadramawt. Electricity services are provided through both the government-owned Public Electricity Corporation’s power plants, as well as several private power plants. In the Wadi Hadramawt region, which relies on gas- and diesel-fired power plants, roughly one-third of the electricity is generated by government-owned plants. The two largest plants in Wadi Hadramawt are the government-owned PetroMasila plant, which currently operates at 33.45 megawatts (MW), and the private Al-Jazeera plant, which currently operates at 20-25 MW.[6] Only two of PetroMasila’s three turbines are currently in use, meaning the plant is operating at approximately 45 percent capacity. The Al-Jazeera plant’s capacity was 50 MW when it went online in 2010, but has been reduced to nearly half that rate due to a lack of maintenance and an inability to meet operational costs following the state’s failure to pay for purchased electricity.[7]

In 2023, the median electricity demand in Wadi Hadramawt region is 220 MW, peaking at about 250 MW during the hottest summer months. However, existing power plants can only provide about 110 MW at any given time, meaning that only 44 to 50 percent of the already insufficient power supply is available to residents. As such, nearly half of the year is dominated by power cuts.

Wadi Hadramawt also suffers from the poor supply of electricity in remote areas. Ameliorating this would require extensive infrastructure and entail high costs. The Ministry of Electricity and Energy envisioned three lines for electric power transmission in remote areas, including an 80-kilometer line, a 45-kilometer line, and a 67-kilometer line, but their combined cost – at more than US$300 million – proved an untenable challenge.[8]

The cost of electricity for consumers in Wadi Hadramawt is about YR120-150 per kW.[9] This cost could be reduced if all power plants in Wadi Hadramawt were gas-fired, given that gas is produced domestically.

In Coastal Hadramawt, the diesel-powered, government-run Al-Shihr and Al-Rayyan stations are the main power plants in the region. The operational capacity of Al-Rayyan power plant was 70 MW when it was built in 1997,[11] but it is currently operating at a capacity of 13 MW. According to experts, the plant’s capacity can be increased to 45-48 MW after maintenance work is completed, which was scheduled to occur by the end of summer 2023 but has been delayed due to financial issues.[12]

The Al-Harshiyat power station[13] in Mukalla is one of the least expensive for the government to operate in Coastal Hadramawt. This is due to the fact that it is powered by inexpensive mazut fuel, allowing the government to pay as little as US$.01 per kW in 2023. By contrast, the government pays about US$.34 per kW at diesel-powered plants due to the higher price of fuel. Because Coastal Hadramawt relies heavily on diesel to operate its plants, the cost of electricity production ranges from YR220-250 per kW for consumers. Experts have told the Ministry of Electricity and Energy that this price could be reduced to as low as YR170 per kW if mazut was used rather than diesel.[14]

The local authority typically helps the central government pay the high cost of fuel for power plants by tapping into its 20 percent share of oil revenues, but this revenue stream has dried up since the Houthi attacks on the Al-Dhabba oil terminal in Al-Shihr district on October 21, 2022, forced the government to suspend oil exports.

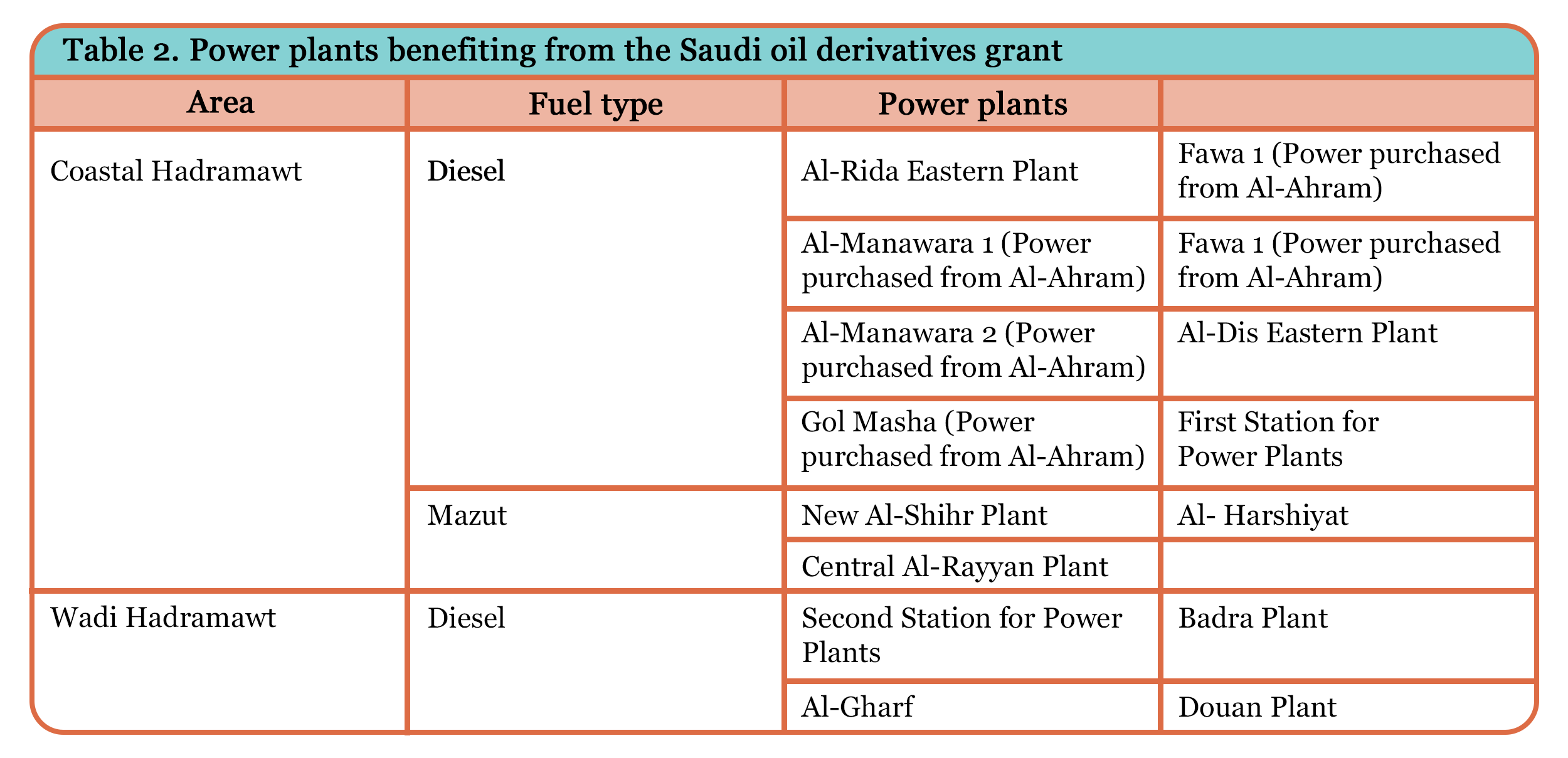

The Yemeni government, in coordination with the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen (SDRPY), has tried to alleviate the situation with the Saudi Oil Derivatives Grant (SODG). Since its establishment in 2021, the SODG has provided over 769,000 metric tons of oil derivatives in four batches. As a condition of receiving the grant, standards were set to raise production efficiency and reduce electricity costs and losses. In both Wadi Hadramawt and Coastal Hadramawt, local authorities have worked towards these goals, but with limited success.[15]

Other challenges the government faces in providing electricity to a cash-strapped populace include an inability to regularly collect electricity bills from residents, the loss of electricity due to dilapidated distribution networks, and the proliferation of consumers tapping into the grid illegally.[17] It is estimated that up to 31.5 percent of electricity is lost in Wadi Hadramawt,[18] and 43.5 percent is lost in Coastal Hadramawt.[19] In the former, 55.6 percent of electricity bills were collected in 2018;[20] 55.4 percent of bills were collected in Coast Hadramawt.[21]

In the face of growing electricity demand,[22] the government has increasingly purchased electricity from private companies.[23] Although an effective stopgap measure, these deals have saddled the government with debt, raised prices for consumers, and created an environment conducive to secretive deals that benefit powerful public officials and business moguls.

Illegal Contracting

Existing public contracting processes in Hadramawt’s electricity sector are an extension of previous unlawful practices, which often involve directly negotiated deals without the competitive bidding required by tender laws.[24] Directly negotiated deals undermine opportunities for a diversity of investors to play a role in the sector. In the absence of a competitive bidding process, bribes, nepotism, and other corrupt practices play a decisive role in who secures a contract. Furthermore, the lack of oversight and transparency makes it difficult to determine whether the deals are implemented according to the contractual obligations.

This pattern can be seen in the construction and operation of the Al-Dhlia’ah central power plant project. The plant, which has a capacity of 20 MW, was awarded a contract in 2021 to supply electricity to Al-Dhlia’ah, Yabuth, and Douan districts in western Hadramawt.[25] The US$17.6 million contract was awarded directly to the Itihad al-Mawarid Trading and Contracting company without a competitive bidding process.

Direct contracting methods were again used for a US$40 million deal with the Al-Ahram Taqa company, which completed construction of the 40 MW Awadh Al-Socatri power plant in Al-Shihr district in 2021,[26] and for a US$25.5 million contract with the Finnish Wartsila Company in 2022 for the maintenance and rehabilitation of the Al-Rayyan Central Power Plant.[27] As of September 2023, Wartsila is more than a year behind schedule in completing the project.[28]

Directly negotiated electricity contracts signed between the Public Electricity Corporation in Hadramawt, the Ministry of Electricity and Energy, and the privately owned Hadramawt Investment Power Company also entailed corrupt practices. Prominent among them was the use of government-subsidized fuel to power an iron and steel factory affiliated with the Hadramawt Investment Power Company rather than to power the Al-Harshiyat plant to provide electricity to the public.[29] In July 2022, armed forces and local authority officials raided the Al-Harshiyat power plant and suspended its operations.[30]

These lucrative and secretly negotiated electricity deals have burdened the government’s budget while failing to meet increasing electricity demand in Hadramawt. In June 2020, the central government was US$94.7 million in debt to the Hadramawt Investment Power Company for electricity purchased between 2010 and April 2022.[31] The government is US$33 million in debt to the Al-Ahram Taqa Company for electricity purchased from 2016 to 2022.[32] According to Minister of Electricity and Energy Manea Benyamin, Hadramawt is now trapped in a vicious cycle, in which “demand is increasing but not matched by an increase in energy production.”[33] This has not only discouraged investment but left residents with chronic electricity shortages and little hope for improvement.

The massive deficit in power supply and a lack of improvement in the management of electricity services have inevitably led to widespread protests and unrest across Hadramawt.[34] This has included citizens blocking roads, setting fires, and staging public demonstrations in front of government institutions. In June 2023, citizens took to the streets in Al-Shihr and Al-Ghail Ba Wazir districts to protest power outages that exceeded five hours a day.[35]

Legal Framework Governing Public Contracting

In order to understand corruption related to public procurement in Hadramawt, it is important to review the existing contracting legislation and its application.

- Under Article 16 of the Executive Regulations of Law No. 23 for the Year 2007 Concerning Tenders, Auctions, and Government Storehouses, the public contracting process should be conducted through a public tender and announced both inside and outside of Yemen, depending on the tender type.

- Under Article 60, a Tenders Committee shall be established, with the authority to award all tenders. The article also stipulates that various figures in the local authority should assume certain positions within the committee. (For example, the governor should serve as the committee’s chairman.)

- Under Article 511, public tenders should be announced in the name of the relevant body in the central authority and in the name of the concerned local council. Announcements should be published on the relevant body’s website and in two official daily newspapers that are widely circulated for three consecutive days. Additionally, the announcement should be published in at least one foreign newspaper, in both Arabic and English, in order to attract international bids.

- Under Article 611, bids should be submitted no more than 30 days from the date of publication of the first announcement. For tenders where the estimated value exceeds YR500 million (approximately US$343,000, as of October 2023), bids should be submitted within 45 days. In this case, tenders will be referred to the High Authority for Tenders and Auctions, as the local authority’s financial ceiling is capped at YR250 million (approximately US$171,000).

According to experts, many policies currently in place violate these regulations. Calls for tenders are not publicly issued. Tenders are rarely announced, instead “the authority resorts to signing contracts with a specific party” that then becomes the sole supplier for the project.[36] On rare occasions where tenders are issued, they are usually announced for only half of the legally required period. Furthermore, calls for tenders are often issued only in local districts, while the vast majority of tenders and auctions in Hadramawt’s capital Mukalla are “conducted by awarding direct contracts.”[37]

To combat this pattern, the cabinet approved the Transparency and Anti-Corruption Action Plan on October 9, 2012, which obligated central and local authorities to post tenders and announce bidding documents for contracts worth more than YR50 million. It also worked to put all government tenders on the national tenders’ portal, known as the Procurement Management Information System (PMIS).[38] Finally, the plan stipulated that payment should not be released under directly awarded contracts, or those not posted on the PMIS, and parties who engage in these practices should be penalized.[39]

Nonetheless, contracts continue to be awarded directly and opaquely, with little regard to existing policies or legal safeguards. This has resulted in a lack of transparency throughout contracting processes and resulted in deals that are made with questionable rationale and poor criteria.[40]

Efforts to Combat Corruption

Hadramawt has for the most part been spared the on-and-off frontline fighting experienced in other governorates during the war. The exception occurred between April 2015 and April 2016, when Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) took control of Hadramawt’s capital Mukalla city, before being expelled by 2nd Military Region forces, with support from the UAE.[41] However, the jihadist takeover had lasting effects on the governance of Coastal Hadramawt in particular, and the wider governorate. After Mukalla’s liberation from AQAP in April 2016, the role of local councils was suspended,[42] leaving a significant void in local governance. The administrative bodies of the local councils[43] also stopped their work. In the absence of the local councils and their affiliated administrative bodies, the majority of government contracting decisions were passed with little to no oversight. As the situation calmed down, local councils resumed some of their work, but in general have “remained idle.”[44] This has impeded oversight at both the district and governorate levels. As a result, “internal controls in government institutions have declined and their role has become very weak.”[45]

Hadramawt’s contracting process also suffers from a lack of judicial accountability, as many violations are not brought before appropriate courts. According to one government official, even when cases are brought before the court, the judiciary is often unresponsive, causing many cases to be thrown out.[46] Simultaneously, civil society organizations concerned with transparency and corruption do little to hold local authorities accountable, preferring to avoid confrontation on the issue.[47]

As stipulated by Article 64[48] of the tenders law, tenders committees are subject to supervision by three main bodies: the High Authority for Tender Control (HATC),[49] the Supreme National Authority for Combating Corruption (SNACC), and the Central Organization for Control and Auditing (COCA). During the war, however, the governor’s office has monopolized decision-making in issuing contracts. This has made tenders committees at the governorate and district levels effectively obsolete, leading to an absence of competitive bidding and allowing the governor to hand-pick contractors. Many of these deals also lack feasibility studies, which opens the door to a host of other problems.

In October 2022, COCA issued a report that called on Hadramawt’s newly-appointed governor, Mabkhout bin Madi, to establish tenders committees at both the governorate and district levels, review existing directly-awarded contracts, and terminate all contracts that were directly awarded but had not yet gone into effect.[50] Although there appears to have been no progress in implementing COCA’s recommendations, they were an important step in identifying corrupt practices in Hadramawt’s electricity contracting processes and providing a road map for the next steps.

In January 2023, in an effort to reinstate competitive bidding in Hadramawt and curb corruption, SNACC sent a memorandum to Governor Bin Madi, directing his office to submit copies of bidding contracts from all offices and government departments as soon as they were concluded. Importantly, the memorandum did not concern previous contracts that had been concluded in violation of the law.[51] Three months later, in response to the memo, the local authority in Hadramawt and SNACC signed a memorandum of understanding pledging to “promote the principles of integrity, transparency, and good governance.”[52] Since then, virtually no progress has been made to pursue these principles or address malpractice in the contracting process, indicating that there is insufficient political will to curb corruption.

Conclusion

Electricity provision is one of the largest challenges facing government officials in wartime Hadramawt. There is steadily rising demand in a governorate that experiences extremely high temperatures in summer,[53] and whose population is widely dispersed across remote, rugged terrain. The local authority has sought to meet these challenges by procuring new power plants, maintaining and repairing old ones, and negotiating agreements to expand the grid through the purchase of electricity from private providers. However, many of these deals violate tender regulations, lack transparency and oversight, and have served to enrich influential public officials and business moguls rather than improve electricity provision. In order to increase transparency and combat corruption in the public contracting process, interested parties must work to expose corrupt practices, undermine any gains from these practices, and impose penalties on those who engage in future such deals.

Recommendations

To Local authorities, national authorities, and local stakeholders:

Investigate Corrupt Practices in Public Contracting

Relevant parties, including the executive, the cabinet, parliament, the judiciary, local authorities, the COCA, and the SNACC should first work to investigate corrupt practices in the electricity sector. This should include a formal review of previous contracts to identify whether contracts were competitively awarded and publicly announced in accordance with the tenders law. To overcome the COCA and SNACC’s failures in similar efforts, these bodies should be restructured in line with the outcomes of the Riyadh Agreement of 2019, reorganizing and reactivating their oversight role. Their respective leaderships of COCA and SNACC should also be replaced. The HATC must also be reconstituted.

Contracts found in violation of the tenders law should be referred to the attorney general’s office and specialized courts. In order to overcome the unresponsiveness of the judiciary, coordination between the anti-corruption agencies and the judiciary should be enhanced, and safeguards should be implemented to insulate the judiciary from interference from the executive authority. In addition, steps should be taken to strengthen Yemen’s national strategy to combat corruption utilizing modern techniques of investigation, law enforcement, and asset recovery.

Build the Capacity of Local Government Institutions

Local authority employees dealing with public contracting should be trained on good governance principles[54] in order to ensure future deals are conducted in accordance with existing tender and anti-corruption laws, with a particular focus on adhering to legal provisions set out by the tenders law. This can be accomplished through courses on the rules of professional conduct, ethical guidelines, and accountability. The training should be mandatory to provide a deeper understanding of relevant laws and promote sound practices in public contracting processes. The national anti-corruption agencies could conduct these trainings.

Encourage Community Engagement

Local authorities, anti-corruption agencies, and civil society groups should organize public consultations, citizens’ committees, and community forums to increase public engagement in decision-making processes concerning public contracting. These community spaces should address specific issues that plague the electricity sector, including transparency in awarding contracts, weakness of supervisory bodies, and financial accountability. An anonymous forum or message board could also be included to protect the identity of concerned citizens, mitigate risk, and encourage open participation.

Local authorities should simultaneously work to placate civil unrest by continuing to improve electricity services through investment in infrastructure, increasing power plant capacities, and ensuring regular maintenance. It is imperative, however, that these efforts are not undertaken at the expense of good governance principles. Officials should prioritize fair and transparent contracts, rather than potentially corrupt quick fixes to appease short-term public dissatisfaction.

Digitize Public Contracting Processes

The local authority should adopt a governorate-level electronic system to digitize public contracting in Hadramawt’s electricity sector. This will help reduce costs by simplifying and optimizing the contracting cycle and reducing the number of workers involved in the contract-awarding process. The system should be designed to enhance information sharing, ensure policy compliance, and promote transparency by making information available to the public, potential bidders, and other relevant stakeholders. This will promote an open bidding process, discourage direct contracts, and help archive contractual records, thus ensuring overall transparency in contract-awarding decisions. A governorate-level system is needed because the national system, known as the Procurement Management Information System (PMIS), is run by HATC, a Sana’a-based body under the control of the Houthi authorities. The services of foreign companies experienced in designing and operating such systems can be solicited.

This policy brief was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies in partnership with Saferworld, as part of the Alternative Methodologies for the Peace Process in Yemen program. It is funded by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO).

- “Overview of Hadramawt governorate [AR],” National Information Center, accessed September 4, 2023, https://yemen-nic.info/gover/hathramoot/brife/

- Ammar al-Aulaqi, “The Yemeni Government’s Triangle of Power,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 9, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/11542

- “Governor Al-Bahsani: The government transfers, for the first time, Hadhramaut’s percentage of oil revenues,” Aden Al-Hadith, December 3, 2017, https://aden-alhadath.info/posts/26036

- Mohammed Rajeh, “Darkness Generates Wealth: Yemen Electricity in the Grip of Corruption and Warlords [AR],” The New Arab, November 26, 2022, https://tinyurl.com/yck2ma5u; “Yemen… Protests in Mukalla due to a power outage [AR],” The New Arab, July 16, 2019, https://tinyurl.com/4sra4t43; “What is behind the mass protests in Hadramawt? [AR],” Qposts, September 16, 2021, https://tinyurl.com/3y8bdnwd

- “Prime Minister’s Resolution No. (53) of the Year 2009 of the Executive Regulations of Law No. (23) for the Year 2007 Concerning Tenders, Auctions and Government Storehouses,” High Authority for Tender Control, 2009, https://hatcyemen.org/upload/iblock/0aa9d7246323bd4f3bd3f9e8c692e2a8.pdf

- The government purchases electricity from this plant at a cost of US$.06 per kilowatt (kW).

- Interview with Minister of Electricity and Energy Manea Benyamin, May 20, 2023.

- Ibid.

- Based on an exchange rate of YR1,000 per US$1 quoted by Minister of Electricity and Energy Manea Benyamin.

- “Annual report of the activities in the liberated areas for 2018 [AR],” Ministry of Electricity and Energy, General Administration of Planning and Statistics, Aden, 2018, pp. 34 and 39. This is the most recent year for which comprehensive official statistics were published on Hadramawt’s electricity sector.

- Abdullah al-Shadli, “The electricity sector in Hadramawt: between influence struggles and marginalization of investment [AR],” South24, January 5, 2022, https://south24.net/news/news.php?nid=2366

- Interview with the Minister of Electricity and Energy Manea Benyamin, May 20, 2023.

- Al-Harshiyat is affiliated with the Hadramawt Investment Power Company Ltd., a private company led by businessman Sheikh Yahya Abdelrahman Bajrash. Al-Harshiyat was omitted from the Ministry of Electricity and Energy’s annual report of activities in the liberated areas for 2018 and is thus not represented in Table 1 above.

- Interview with Minister of Electricity and Energy Manea Benyamin, May 20, 2023.

- Ibid.

- “List of stations benefiting from the grant,” The Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen (SDRPY), https://saudioilgrant.org/ar/province

- “Report of the Parliamentary Fact-Finding Committee on Allegations of Irregularities in the Oil, Electricity, Communications and Financial Sectors (May – July 2023) [AR],” Parliament of Yemen, August 24, 2023, pp. 16-17.

- “Annual report of the activities in the liberated areas for 2018 [AR],” Ministry of Electricity and Energy, General Administration of Planning and Statistics, Aden, 2018, p. 37.

- Ibid, p. 32.

- Ibid. p. 37.

- Ibid, p. 32.

- Prior to the war, Hadramawt’s annual rate of increase in electricity demand ranged from 6-9 percent, but rose to 17 percent annually between 2016 and 2023 due to the relative stability in Hadramawt compared to other governorates, reflected in part by the growing electricity demands by factories in the governorate. Interview with the Minister of Electricity and Energy Manea Benyamin, May 20, 2023.

- A power purchase agreement (PPA) is typically between a private developer of power generation projects and a public sector purchaser of the electricity generated through these projects. In this policy brief, we usually refer to the Hadramawt’s Public Electricity Corporation as the purchasing party, which is responsible for distribution of the electricity purchased from private energy companies. Under certain conditions, PPAs can be beneficial to all parties involved, including consumers. During Yemen’s war, PPAs have emerged as a stopgap measure that allows the government to expand the electricity supply to meet demand, but in doing so gives the private power companies significant leverage over both the government and consumers. Because PPAs are paid in US$ and Yemen’s central bank has a shortage of foreign reserves, the government’s payments are often late and large debts accrue. The power plants, in turn, suspend services which fuel street protests against the government and are used as leverage to make the government pay the debts.

- In the era of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, officials would adhere to tender laws only on select contracts. For Saleh’s pet projects, he would award clients and/or allies exorbitant contracts with no strings attached. Interview with Yemeni political analyst, September 8, 2023.

- “The Governor of Hadramawt signs an agreement to launch project of central power plant of Adh-Dhlia’ah [AR],” Aden Al-Ghad, March 16, 2021, https://adengad.net/public/posts/533088

- “Implemented by Al-Ahram Taqa, Prime Minister inaugurates the 40 MW power plant named after late Engineer Al-Socotri in Al-Shihr [AR],” Maz Press, April 27, 2021, https://mazpress.com/news6713.html

- “25.5 Million dollars – Hadramawt governor signs contract for the rehabilitation of Al-Rayyan power plant [AR],” Al-Ayyam newspaper, March 26, 2022, https://www.alayyam.info/news/8YBHEHLO-VIK5W4-31F3

- “Hadramawt governor inspects the progress of work in the rehabilitation of Al-Rayyan power plant and stresses commitment to the schedule [AR],” Aden Al-Ghad, February 25, 2023, https://adengad.net/posts/668339

- “Official documents reveal major corruption in the electrical power purchasing station in Hadramawt [AR],” Al-Rai Press, November 10, 2020, https://m.alraipress.com/news57966.html

- “Bajrash: A military force closed the Al-Harshiyat coastal electricity station [AR],” Al-Ayyam, July 17, 2022, https://www.alayyam.info/news/92RJ4I7N-HFS570-A025; Saeed Nader, “Details of stopping the work of a power station in Hadramawt [AR],” Al-Mushahid, July 17, 2022, https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:VksPzLKaVbMJ:https://almushahid.net/97874/&cd=11&hl=ar&ct=clnk&gl=eg

- Hadramawt TV, “The director of purchased energy in Coastal Hadramawt to Hadramawt TV [AR],” Facebook, June 20, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/hadramouttv/posts/pfbid02sys25xvWLrW879tfeQJgumm5hmsZ2kzfgiAD6mJKjFvit1zCsMwLHZaneeswek38l

- Ibid.

- Interview with Minister of Electricity and Energy Manea Benyamin, May 20, 2023.

- “Yemen… Protests in Mukalla due to a power outage [AR],” The New Arab, July 16, 2019, https://tinyurl.com/4sra4t43; “What is behind the mass protests in Hadramawt? [AR],” Qposts, September 16, 2021, https://tinyurl.com/3y8bdnwd

- “Hadramawt witnesses protests against power outages [AR],” Al-Mahriah, June 19, 2023, https://almahriah.net/local/29178

- Interview with Hamdi Abboud Shaaran, a member of the Tenders Committee in Seyoun district, January 23, 2023.

- Interview with a source in the Central Organization for Control and Auditing (COCA), January 22, 2023.

- “Procurement information system project [AR],” High Authority for Tender Control (HATC), https://hatcyemen.org/about_us/info_unit/; HATC, the body that manages the portal, is based in Sana’a and has been under the control of Houthi authorities and their allies since the start of the war, which prevents pro-government authorities in governorates like Hadramawt from utilizing it.

- “Yemen Accountability Enhancement Project (PI48288) [AR],” World Bank Report, 2014, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/491961468196174232/text/PIDA2529-PID-ARABIC-P148288-Appraisal-Box394882B-PUBLIC-Disclosed-4-4-2016.txt

- Interview with a source in the Central Organization for Control and Auditing (COCA), January 22, 2023.

- Tawfeek al-Ganad, Gregory D. Johnsen, Mohammed al-Katheri, “387 Days of Power: How Al-Qaeda Seized, Held and Ultimately Lost a Yemeni City,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, January 5, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/12247 Tawfeek al-Ganad, Gregory D. Johnsen, Mohammed al-Katheri, “387 Days of Power: How Al-Qaeda Seized, Held and Ultimately Lost a Yemeni City,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, January 5, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/12247

- “Local governance is the engine of Yemen’s stability,” Globalview, October 2017, https://pdsp-yemen.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Towards-local-governance.pdf, p. 14. The local councils were suspended as a precautionary step because most of its leaders were linked to former President Saleh’s General People’s Congress party, whose military units in Mukalla city handed over the city to Al-Qaeda fighters.

- For a chart showing key administrative structures of local authorities in pro-government governorates, see Omar Saleh Yaslm BaHamid, “Wartime Challenges Facing Local Authorities in Shabwa,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 10, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/11641

- Interview with an official at the Central Organization for Control and Auditing (COCA), January 22, 2023.

- Interview with an official in the Executive Office of Wadi Hadramawt, February 1, 2023.

- Interview with an official in the Executive Office of Wadi Hadramawt, February 1, 2023.

- Interview with Hamdi Abboud Shaaran, member of the Tenders Committee in Seyoun district, January 23, 2023.

- “Prime Minister’s Resolution No. (53) of the Year 2009 of the Executive Regulations of Law No. (23) for the Year 2007 Concerning Tenders, Auctions and Government Storehouses,” High Authority for Tender Control (HATC), https://hatcyemen.org/upload/iblock/0aa9d7246323bd4f3bd3f9e8c692e2a8.pdf, p. 38

- HATC is also referred to as the High Authority for the Control of Tenders and Auctions and the Supreme Authority for the Control of Tenders and Auctions in English-language publications.

- Interview with a source in the Central Organization for Control and Auditing (COCA), January 22, 2023. Details mentioned were taken from the report submitted to the Hadramawt governor’s office.

- Interview with Judge Afrah Badwilan, head of the Supreme National Authority for Combating Corruption (SNACC), February 4, 2023. This is within the authority’s legal right, as stipulated by Article (8) of Anti-Corruption Law No. (39) of 2006, which allows the central government to terminate any contracts found to be in violation of applicable laws. See “Law No. (39) of 2006 regarding combating corruption [AR],” Yemen Parliament, December 2, 2018, https://yemenparliament.gov.ye/Details?Post=483

- “Signing in Mukalla of a memorandum of understanding between the local authority in Hadramawt and the Supreme National Anti-Corruption Authority to promote the principles of integrity, transparency and good governance [AR],” Supreme National Authority for Combating Corruption (SNACC), March 1, 2023, https://www.snaccye.org/2018101/1644-2023-03-01-15-10-54

- Coastal Hadramawt experiences temperatures that exceed 35 Celsius (95 Fahrenheit), combined with high humidity.

- According to UNDP, “Good governance is characterized as participatory, transparent, accountable, effective, equitable, and promoting the rule of law.” See “Governance for Sustainable Human Development: a UNDP policy document,” United Nations Development Program, Jan. 1997, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/492551?ln=en, pp. 2-3.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية