The Sana’a Center Editorial

Aid Must Do More Good than Harm

Many of the challenges facing humanitarian operations in conflict zones today are well known. Any package of assistance must survive the politics of individual donor countries before it even starts the journey down the pipeline to the United Nations and other aid agencies. From there, it navigates a maze of bureaucracy between headquarters and destination countries, often running the gauntlet between warring parties and local realities before hopefully making its way to people in need. Humanitarian operations, wherever in the world they occur, are almost certainly flawed.

The politicized and financially constrained structures that international aid must traverse mean no single agency bears responsibility. While many individuals working within the humanitarian community certainly do their best to make the system work better where they can, it remains reasonable to expect that humanitarian aid does more good than harm. At a bare minimum, humanitarian aid should reduce the suffering of the most vulnerable. Whether that is the case in Yemen today is, at best, unclear.

Last week, the Sana’a Center published a six-part report series examining UN-led humanitarian operations in Yemen since 2015, when the war escalated and the humanitarian emergency response began. While the UN regularly claims that Yemen is the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, the findings of the research would suggest that instead Yemen hosts among the world’s worst humanitarian responses. The fault lies first and foremost with the aid system and its leadership, both within and outside of Yemen. This stands in stark contrast to the tendency of senior leaders in the humanitarian effort to blame the failures of the response exclusively on the warring parties.

Yemen’s fundamental challenges are rooted in longstanding development issues, which have only been exacerbated by the current conflict. After the onset of war, long-term international development projects stopped and humanitarian operations began. But the latter are meant to be short-term responses to sudden, large-scale catastrophe, and to some degree such aid will continue to be required until there is peace. Humanitarian aid does not solve systemic problems, and should not be expected to do so.

The humanitarian response to the war started poorly in 2015. It supported institutions run by warring parties, centered almost all operations in Houthi-held Sana’a and failed to branch out substantively beyond the capital; it also prioritized security over aid delivery and lost sight of basic principles of independence and neutrality. And there was no course correction. Instead, these mistakes became entrenched as institutional investment built behind them, aided by the extraordinary success of the UN’s fundraising effort, which was galvanized by its claim that Yemen is on the brink of famine. To date, humanitarian operations in Yemen have received more than US$17 billion, making Yemen the most expensive international relief effort in the past decade, other than Syria.

The UN’s consistent narrative that famine is imminent, however, misrepresents the situation. Famine is not the key issue facing Yemen. Rather, the key issues are food security, malnutrition, access to water and problems related to purchasing power. There is food available, but people struggle to afford to buy it. Endlessly delivering food baskets does not help people develop the means (or the money) to feed themselves. In fact, this form of rapid response helps to reproduce the kinds of food insecurity that Yemenis experience because it diverts attention from the deeper structural issues at play – and the emergency food supplies are readily diverted to fund the war.

The UN’s flawed narrative regarding Yemen has gone generally unchallenged because the humanitarian response has normalized the use of incomplete, skewed, and decontextualized data to guide its operations, which has then been easily reframed or discounted according to the prerogatives of the senior leadership. The activities of the response have also been dominated by security priorities rather than humanitarian ones, allowing the former to undermine rather than enable the latter. This has prevented aid workers from venturing into the field to collect the data necessary to gain an accurate assessment of population needs and to work more directly with local communities, improving acceptance, safety and appropriate response. The humanitarian response has also outsourced many of the basic functions of data collection and aid delivery to the warring parties themselves, who have a vested interest in what the data shows and where the aid goes. In doing so, the response has in many ways become a support system for the warring parties, in particular the armed Houthi movement.

In the runup to publishing this series of reports, we at the Sana’a Center wrestled with the question of whether going ahead could ultimately do more harm than good to vulnerable Yemenis. The country’s needs are real and massive, even if the broken and misdirected humanitarian response is not addressing them effectively. We also debated whether publication would give donor countries an excuse to throw up their hands and abandon Yemen. Such moral abdication on the part of the international community, to leave unfixed a mess they helped create, would only amplify Yemen’s ongoing tragedy for years to come. Our hope is that this does not happen and that, instead, our series of reports prompts the UN and other donors to admit that how they are currently pursuing the humanitarian response in Yemen is failing to meet basic benchmarks and that they begin the difficult endeavor of reforming their processes – for which our reports offer several key recommendations.

Moreover, as a Yemeni research center whose core mission is the production of knowledge, we should not be in this position. The UN should have in place mechanisms and frameworks for accountability to prevent situations such as this. Donor countries should make sure that the funds they provide genuinely address the needs of the intended recipients, and actually reach them. It is hard to miss the irony of a Yemeni organization struggling with the ethical implications of holding the international humanitarian effort and its donors to account, while those same agencies and frameworks regularly refuse to support local Yemeni organizations for fear that they are at a higher risk of corruption or misusing funds.

Ultimately, when something is badly broken, it must be fixed. Those most in need deserve the support of the international community. Yemenis deserve an aid system that does not sustain the war and that is not preoccupied with preserving its own bureaucratic structures and processes.

Contents

- How Outsiders Fighting for Marib are Reshaping the Governorate – By Casey Coombs and Salah Ali Salah

- Forgotten War, Abandoned Refugees: The plight of Yemenis in Lebanon – By Ali al-Dailami

- Book Excerpt: The Day the Gunmen Came – By Abdulkader al-Guneid

October at a Glance

The Political Arena

By Casey Coombs

Developments in Government-Controlled Territory

STC-Islah Forces Clash in Aden

On October 1, clashes broke out between Security Belt forces and fighters loyal to an Islah-affiliated Salafi commander known as Imam al-Noubi in Aden’s Crater district. At least 10 combatants were killed and dozens more were injured in the two-day battle, which erupted as part of a wider conflict over control of the interim capital and competition across southern governorates.

The fighting started after Al-Noubi’s forces carried out a jailbreak from a police station in the district to which Security Belt forces responded. Al-Noubi, whose real name is Mohammed Ahmed Abdulsalwi, is the half-brother of Brigadier General Mukhtar al-Noubi, a former commander of the 5th Support Brigade in Al-Dhalea governorate and current commander of the Abyan axis, both of which are loyal to the Southern Transitional Council (STC). In 2015, Imam al-Noubi led an armed group fighting Houthi-Saleh forces, helping to drive them out of Aden. In the process, he established control of an important military base in Crater known as Camp 20. Although Al-Noubi officially resigned from his command a few days after President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi ordered the closure of the camp in late October 2017, he remained in Crater. The UN Panel of Experts on Yemen investigated several cases of harassment, torture and assassinations allegedly carried out by Al-Noubi’s forces at Camp 20 against journalists, pro-secession southern activists and suspected atheists in Aden.

UN Envoy Visits Aden in First Official Trip to Yemen

On October 5, the new UN special envoy to Yemen, Hans Grundberg, arrived in Aden for a day of meetings with officials in the STC and the internationally recognized government. In his first official visit to Yemen in his new role, Grundberg met several senior Yemeni officials, including Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed, Aden Governor Ahmed Lamlas, STC Chairman Aiderous al-Zubaidi and Taiz Governor Nabil Shamsan. The envoy also spoke with members of the Hirak movement, the Inclusive Hadramawt Conference and civil society organizations as well as women’s rights activists.

Aden Governor Targeted by Car Bomb

On October 10, a car bomb explosion targeted the convoy of Lamlas, Aden’s governor, and Agriculture Minister Salem al-Soqotri in the interim capital. At least six people died in the attack, including three civilians, and 11 were injured. Lamlas and Al-Soqotri, both of whom are STC members, escaped the attack unharmed. The explosives-laden car was parked on the side of the road in Aden’s Al-Tawahi district. Security sources told AFP that the governor and the minister were not in the armored vehicle targeted in the attack, which Hadi called a “terrorist operation”.

Taiz Islah Leader Assassinated

On October 23, a top leader in the Islah party in Taiz, Dhia al-Haq al-Ahdal, was shot dead in the governorate capital, Taiz city. Unidentified gunmen on a motorbike fired on Al-Ahdal as he left his home in the city. Early on in the war, Al-Ahdal had helped form anti-Houthi resistance forces in the city and was involved in negotiations for prisoner exchanges throughout the conflict. A week before he was killed, Al-Ahdal participated in a meeting at which he supported an alliance between UAE-backed National Resistance Forces based on the Red Sea Coast and the pro-Islah Taiz Military Axis, which is aligned with the internationally recognized government, to fight the Houthis. On October 28, the STC announced its willingness to partner with the National Resistance Forces against the Houthis.

Car Bomb Explodes Outside Aden Airport

On October 30, a car bomb detonated near the entrance to Aden’s airport, killing at least 12 civilians and injuring at least 30 others. The attack happened a day after a high-ranking European diplomatic delegation left the interim capital and 20 days after a car bomb attack targeted the convoy of Aden’s governor in Al-Tawahi district.

Journalists Detained, Targeted and Killed

Journalists in areas nominally controlled by the internationally recognized government were targeted by a variety of actors in recent weeks. On October 8, security forces affiliated with the STC arrested sports journalist Ammar Makhshef at his home in Crater district. Ten days earlier, the STC’s Security Belt forces in Mansoura district stormed the building of Aden FM Radio in search of its director, Raafat Rashad Baki. When Baki reported to Security Belt forces headquarters a day later to inquire about the incident, he was detained and transferred to a base in Aden’s Al-Tawahi district. Baki’s relatives said that despite submitting an official inquiry to the Aden Security Department, they had not received any information about his condition, location or why the arrest took place. Makhshef and Baki remained in STC custody as of the time of writing.

On October 10, the Aden governor’s press secretary, Saleh Bussalh, and photographer Tariq Mustafa were killed in the car bomb that targeted the governor’s convoy.

On October 22, photojournalist Mofeed al-Ghilani was attacked by three unidentified gunmen while working near Bab Musa in the center of Taiz city. Al-Ghilani said he filed a police report on the incident but the authorities had yet to open a case. In March 2020, Al-Ghilani was attacked in another neighborhood in the Taiz capital where he was filming.

The Yemen Journalists Syndicate’s latest quarterly report on violations against journalists and media throughout Yemen stated that between July 1 and September 30, eight journalists were kidnapped, arrested or prosecuted, four were tortured in detention, four were denied medical care in detention, four received threats, three photographers were prevented from doing their work or had their cameras confiscated, two media outlets had their operations suspended and the homes of two journalists were raided. The report attributed nearly half (13) of the 27 documented violations to the Houthis, eight to forces loyal to the internationally recognized government and three to STC-affiliated forces. Three other incidents were carried out by unknown parties.

Developments in Houthi-Controlled Territory

Houthi Authorities Tax Citizens for the Prophet’s Birthday

In early October, Houthi authorities in the capital of Ibb governorate imposed a range of new taxes and fees on merchants and residents ostensibly to fund celebrations of the Prophet Mohammed’s birthday on October 18. Residents in Al-Zahhar and Al-Mushnah areas of Ibb city said Houthi officials delivered letters to their homes, citing special conditions to justify the new levies. Meanwhile, students in several schools in the district of Jibla, just south of Ibb city, were required to pay 1,000 Yemeni rials. Many residents reportedly refused to pay the fees, complaining about recent taxes imposed for the seventh anniversary of the Houthis’ September 21, 2014, coup in Sana’a. In addition to paying the taxes, NGOs and private businesses were required to hang flags and other green decorations in their buildings on the Prophet’s birthday.

On October 3, the Houthi-run government in Sana’a approved a proposal by senior leader Mohammed al-Houthi to deduct an annual fee from the salaries of public servants to establish medical facilities in the name of the Prophet, according to Houthi-run Saba news agency. The move was widely criticized, as the Houthi government has not paid the salaries of civil servants in areas it controls for years while regularly spending on religious and patriotic occasions and military operations in the war. The Houthis regularly use religious justifications to collect money from residents and merchants in the group’s areas of control.

Houthi Authorities Restrict Real Estate Transactions in Sana’a

On October 22, Houthi officials issued a circular preventing real estate transactions in the capital Sana’a without the approval of the Houthi authorities. Activists on social media denounced the move as a new way to extract money from the populace to fund the war efforts. Elsewhere in Houthi-controlled territory, the group recently established Sharia trustees, who oversee all real estate transactions in line with sectarian rules. New taxes are associated with the transactions.

International Developments

Iran Resumes Exports to Saudi Arabia After Year-Long Trade Freeze

On October 18, the latest report of Iran’s Customs Administration listed Saudi Arabia as an export destination for the first time following the complete suspension of bilateral trade during Iran’s last fiscal year. The resumption of Saudi-Iranian trade was viewed by some observers as a positive sign that relations between the regional foes are warming.

Ambassadors Hold Call with Marib Governor

On October 21, the ambassadors to Yemen from China, France, Russia, the UK and the US held a video briefing with the governor of Marib, Sultan al-Aradah, on the dire humanitarian situation in the governorate. The diplomats, whose countries constitute the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, repeated their calls for an inclusive political solution to the Yemen conflict.

Saudi Arabia Holds First Round of Talks with Iran’s New Government

On October 3, Saudi Arabia’s minister of foreign affairs, Prince Faisal bin Farhan al-Saud, announced that the kingdom had held its first round of direct talks with Iran’s newly elected government. The talks, held on September 21 at an undisclosed location, were reportedly part of a process that began in April 2021 to reduce tension between the regional rivals in conjunction with US efforts to revive a nuclear deal with Tehran. Iran’s new President, Ibrahim Raisi, delivered a speech at the UN General Assembly in New York on the same date as the reported meeting.

“These discussions are still in the exploratory phase. We hope they will provide a basis to address unresolved issues between the two sides and we will strive and work to realize that,” Prince Faisal said at a joint press conference during EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell’s visit to Riyadh.

Ex-German Soldiers Sought to Form Mercenary Force in Yemen

On October 20, German police detained two former German soldiers on suspicion of trying to form a mercenary group of up to 150 members to “pacify” the war in Yemen. The men had decided in early 2021 to form a paramilitary unit consisting of former German army soldiers and police members, according to a statement from federal public prosecutors. According to German prosecutors, the suspects were motivated by the prospect of earning about US$45,000 each per month and had unsuccessfully sought financing from Saudi Arabia.

Biden Administration Inks $500 Million Military Cooperation Contract With Saudi Arabia

On October 27, The Guardian reported that the US State Department had authorized a US$500 million contract with Saudi Arabia to support the Royal Saudi Land Forces Aviation Command’s fleet of Apache, Blackhawk and Chinook helicopters. The deal includes training and service involving 350 US contractors for the next two years, as well as two US government staff. First announced in September, the deal calls into question one of the Biden administration’s early foreign policy objectives to end American support for “offensive” Saudi military operations in the war, according to critics. Other analysts argued that the helicopters had been used for defensive missions along the Saudi-Yemeni border. The vague distinction between defensive and offensive operations was a “purposeful attempt to create leeway to pursue military cooperation,” Yasmine Farouk, a scholar at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told The Guardian.

Saudi Arabia and Lebanon fall out over Lebanese minister’s comments on Yemen war

On October 29, Saudi Arabia expelled Lebanon’s ambassador to the kingdom and banned all Lebanese imports in reaction to critical comments made by Lebanon’s Information Minister George Kordahi about the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen. In turn, senior Houthi leader Mohammed Ali al-Houthi urged a boycott of all Saudi imports to Yemen. The controversy stems from an August 5 interview in which Kordahi, a prominent television personality who had worked for Saudi-owned media and was speaking before his appointment as minister, said the Houthis were “defending themselves … against an external aggression.”

Bahrain and Kuwait have followed Saudi Arabia and expelled Lebanon’s ambassadors from their capitals, while the United Arab Emirates has withdrawn its diplomats from Beirut.

Casey Coombs is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and an independent journalist focused on Yemen. He tweets @Macoombs

State of the War

By Abubakr al-Shamahi

Pro-Government Tribes Struggle to Hold the Line in Marib

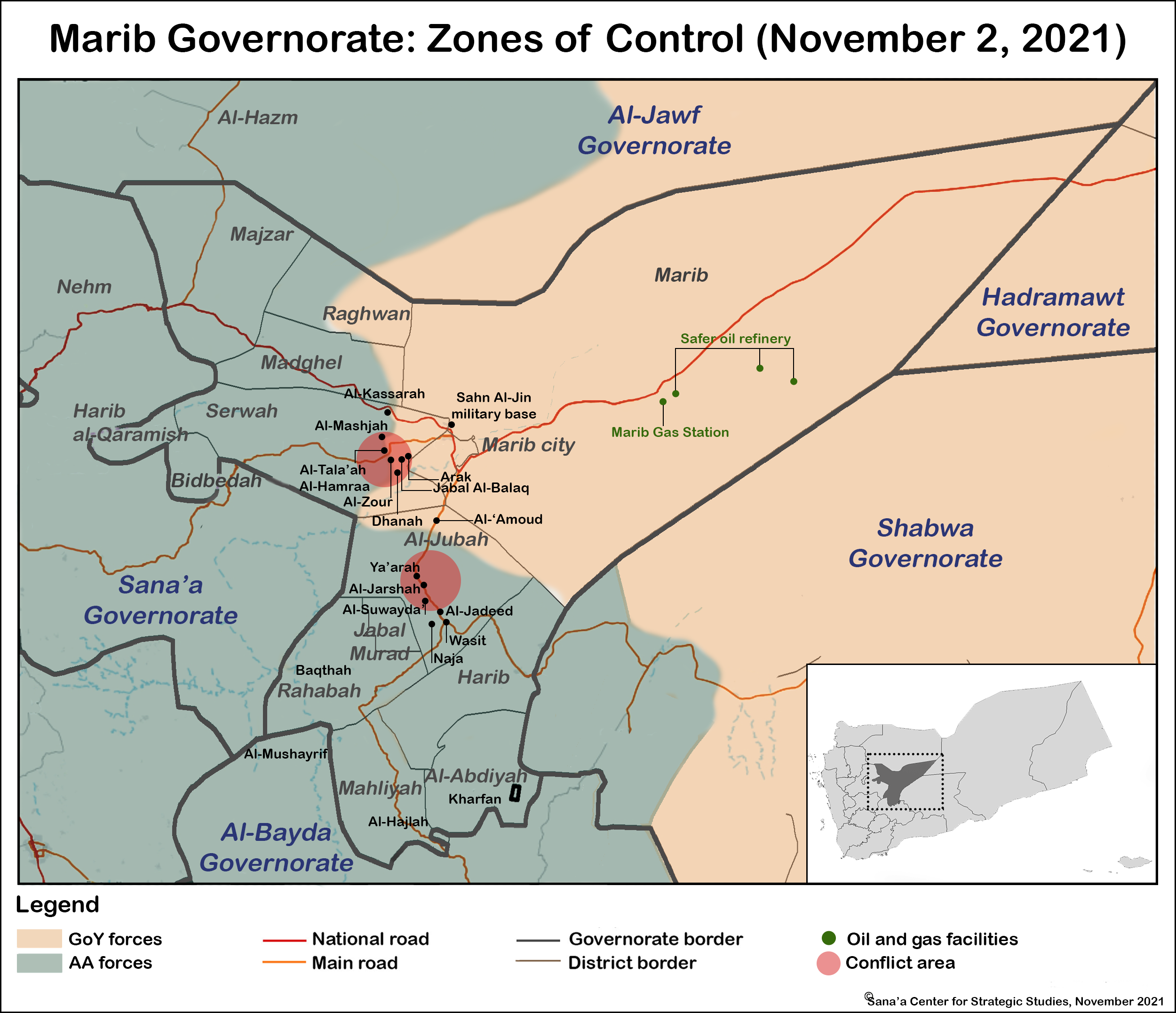

Movements on the military map of Yemen continued to favor Houthi forces in October, with the group making further military advances in Marib and taking territory from government forces in the southern part of the governorate. Perhaps most notable was that to secure this territory, Houthi forces defeated fighters from Marib’s pro-government tribes, especially Murad and Bani Abd. Marib’s tribes have formed the backbone of the fight against the Houthis in the governorate, but without a change in their fortunes – which seems increasingly unlikely – they appear unable to sustain their resistance against Houthi forces.

Houthi advances during the previous month, September, meant that Al-Abdiyah district, in southern Marib, was besieged, with humanitarian conditions there growing increasingly desperate. On October 11, after years of resistance in Al-Abdiyah from the local Bani Abd tribe, the Houthis captured their first village in the district, Al-Masjed. On the same day, Houthi forces advanced deep into eastern Al-Jubah district, a stronghold of the Murad tribe. The next day, on October 12, the Houthis took the Wasit area, in central Al-Jubah. The rapid nature of the Houthi advance into Al-Jubah highlighted the state of disarray among pro-government forces. This was despite the October 11 appointment of a new Yemeni military commander, Brigadier General Mohammed Ahmed al-Halisi, to lead the fight in the district.

In Al-Abdiyah, an increase in Saudi-led coalition airstrikes did little to slow Houthi advances. Bani Abd tribal fighters were left to confront the offensive themselves, with no government reinforcements. On October 15, the Houthis captured the Al-Abdiyah district capital, after local tribal leaders surrendered. Some pockets of resistance held out in western and northern Al-Abdiyah, but the Houthis quickly cracked down on their opponents, raiding villages and arresting them, according to locals who spoke to the Sana’a Center.

The victory in Al-Abdiyah allowed the Houthis to focus additional resources on Al-Jubah, where the Houthi goal was to knock the powerful Murad tribe out of the battle for Marib. On October 25, the Houthis successfully took the Al-Jubah district capital, Al-Jadeed, and cut the sole Yemeni government supply route to neighboring Jabal Murad district, another part of the Murad heartland to the west. Jabal Murad did not hold out for long. On October 26, Murad tribesmen in the district surrendered and, following negotiations facilitated by local tribal sheikhs aligned with the Houthis, Houthi forces entered the district. The agreement stipulated the peaceful handover of Jabal Murad to Houthi forces on the condition that houses would not be raided and residents would not be detained, according to local sources who spoke with the Sana’a Center.

By the end of the month, fighting was taking place in northern Al-Jubah, centered on Al-Amoud village, approximately 20 kilometers from Marib city’s southern entrance. If the Houthis advance farther, they will be able to link up with their forces near Jabal al-Balaq, southwest of Marib city, specifically in an area called Al-Falaj, which government forces have heavily fortified. Since the start of the year, government forces have been able to hold off the Houthis in Jabal al-Balaq and along frontlines to the west of Marib city, but a new attack from the direction of Al-Jubah would pose a significant threat to Marib city..

Houthi missiles continued to target the government’s last stronghold in northern Yemen during the month. On October 20, a missile strike killed six soldiers in the Sahn al-Jin military camp. The civilian death toll from missile strikes also jumped; on October 28, a Houthi missile attack on the home of a tribal sheikh in Al-Amoud killed or injured 13 civilians. Another missile attack on a Salafi religious center in the same village on October 31 killed at least 36 civilians, according to local sources.

Anti-Houthi Forces Fail to Unite in Shabwa

Despite the increasing nature of the Houthi movement’s threat in Shabwa – the group took control of the northwestern districts of Bayhan and Al-Ain and parts of Usaylaan district in September – anti-Houthi forces in the governorate remained divided. Throughout October, there were few signs that these forces would put their differences aside and unite to push the Houthis back. Instead, figures within the internationally recognized government and the STC blamed each other for Houthi forces’ entry into the governorate. Meanwhile, government security forces arrested several pro-STC figures.

The arrests continued a trend that emerged in the district following its full takeover by government forces in August 2019. Then, pro-government forces defeated STC fighters in Shabwa, but many remnants of the main pro-STC grouping in the governorate, the UAE-backed Shabwani Elite forces, remained. Government authorities often accuse these forces of causing instability.

In October, one of the most prominent STC figures arrested in Shabwa was Hassan al-Miti al-Qumayshi, commander of the rapid intervention unit of the Saudi coalition-backed Special Forces and Counterterrorism Brigade, which includes pro-STC members. He was detained in Habban city on October 17. He had been on his way to join Adel al-Mus’abi, the General People’s Congress (GPC)-affiliated commander of the Special Forces and Counterterrorism Brigade. According to tribal sources, this unit has established a training camp in Al-Talh district, near the border with Hadramawt. The establishment of the camp, with backing from the Saudi-led coalition, particularly the UAE, has led to tensions between anti-Islah elements in the governorate and the government authorities in Shabwa, some of whom are affiliated with the Islah party. Figures regarded as Islah allies, such as Shabwa’s governor, Mohammed bin Adio, view the establishment of a new military camp in the governorate, headed by a pro-GPC figure, as an attempt to weaken Shabwa’s current local administration, and replace it with one that will be more friendly to the UAE, local sources told the Sana’a Center.

Against this backdrop, the head of the STC in Shabwa, Ali al-Jabwani, claimed on October 16 that government authorities had rejected an offer from the STC to unite militarily to confront the Houthis. This claim was followed on October 21 by a video widely shared on social media showing Brigadier General Ali Saleh al-Kulaibi – the former commander of the government’s 19th Infantry Brigade who was dismissed from his position in August – claim that the loss of Bayhan, Al-Ain and parts of Usaylaan resulted from the Islah party dismissing and replacing brigade commanders in the districts. The veracity of Al-Kulaibi’s claims could not be confirmed, but frustration with local authorities in Shabwa has increased. Defections from government forces to the STC were also reported in local media outlets toward the end of October.

After a brief lull, fighting in the governorate between government and Houthi forces continued in the second half of October. While there were no real advances for either side, anti-Houthi forces remained on the back foot.

On October 26, UAE forces stationed at Al-Alam military camp, in central Shabwa’s Jardan district, withdrew overland to Saudi Arabia, according to local sources. The withdrawal was also confirmed by Mohsen al-Hajj, an adviser to Shabwa’s governor, who added that Emirati forces would also be withdrawing from the Balhaf LNG facility in the governorate. In August, the local authority led by Governor Bin Adio pressured the UAE to vacate the Balhaf camp. Bin Adio has emerged as a consistent critic of the UAE’s presence in Shabwa and its support for the STC, and has claimed that the UAE tried to kill him in the past.

The Emirati moves appear to be an attempt to avoid any direct confrontation with the Houthis, should the group’s forces expand farther into Shabwa. However, their departure from Al-Alam left a security vacuum; Shabwani Elite forces stationed at the camp refused to hand it over to Yemeni government forces, which led to clashes, the forceful takeover of Al-Alam by pro-government forces, and the subsequent arrest of 30 Shabwani Elite fighters on October 30, who were released on Bin Adio’s orders the next day.

There does, however, appear to be tentative progress in other areas toward bringing together disparate anti-Houthi groups in a common front. Brigadier-General Tareq Saleh announced on October 28 that his Red Sea coast-based Joint Forces were ready to support the Yemeni government’s military against the Houthis across all frontlines. While Saleh has made similar announcements in the past, which have been rejected, his October 28 message specifically mentioned that his forces would work within the government, rather than represent a rival force. On the same day, the STC announced that it would fight alongside Saleh’s forces against the Houthis. Saleh, like the STC, is backed by the UAE.

Abubakr al-Shamahi is an editor and researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

Economic Developments

By the Sana’a Center Economic Unit

Oman’s Salalah Port and Maersk Establish Logistics Partnership to Service Yemen

On October 18, the Port of Salalah in Oman published a press release announcing the launch of an end-to-end logistics service in partnership with Maersk, the Danish international shipping container company, to facilitate the overland transportation of containerized goods through the Al-Mazyunah free zone to Yemen.[1] Services are expected to include the securing of customs clearances and the provision of trucking services to Salalah and Al-Mazyunah free zone hubs under carrier haulage. The partnership will aim to deliver goods to multiple destinations inside Yemen, including Aden, Mukalla, and “other inland destinations.”

During the current Yemen conflict, trade and financial links between Oman and Yemen have expanded. Some Yemeni importers are already importing containerized goods via Salalah port and then overland via Al-Mazyunah and into Yemen via the Shahin land border crossing in Al-Mahra governorate. For some importers, it is more cost-effective to move containerized goods via this trade route than to import them directly via Aden port and the Aden Container Terminal (ACT). Cost factors vary by trader, including demurrage, customs fees and insurance premiums. With a limited number of containers currently being imported via Hudaydah port, ACT accounts for the vast majority of container traffic to Yemen, while Mukalla port also saw a sharp increase in container traffic during the conflict up to the end of 2020.[2]

The partnership between Maersk and Salalah port to target Yemen-bound container business is likely to negatively impact Yemeni seaports in the Gulf of Aden, with reduced container traffic decreasing port revenues. War risk insurance rates could make Salalah port more cost-effective for some traders than having vessels call at Yemeni seaports. Such premiums already have discouraged shipping lines from using Aden for any transhipment operations, with Salalah, Jeddah and Djibouti ports now preferred intermediate destinations.

CBY-Aden Suspends the Licenses of Dozens of Money Exchange Companies

In October, the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) issued several directives and circulars to suspend the businesses and licenses of 71 money exchange companies and seven financial transfer networks. Almost all of these money exchange and financial hawala business establishments were referred to judicial and security authorities for failing to comply with Law No. (19) of 1995, amended by Law No. (15) of 1996, as well as with the CBY-Aden instructions regulating exchange and hawala business activities. CBY-Aden accused the listed exchange companies of engaging in currency speculation and called on traders, citizens and licensed money exchange companies to stop dealing with them while their licenses were suspended.

The flurry of directives from CBY-Aden represents its latest attempt to introduce tighter regulations against money exchangers and assert its authority in the ongoing economic competition with the Houthis and the Central Bank of Yemen in Sana’a (CBY-Sana’a).

The first decree came on October 16 when CBY-Aden announced the suspension of licenses for 54 money exchange companies.[3] These included several prominent businesses, such as Al-Nasser Exchange Company, Al-Jazeera Bros. Exchange Company and Al-Morisi Exchange Company. Two days later, CBY-Aden suspended the licenses of 17 additional money exchange companies and outlets.

Eleven of the license suspensions were implemented on October 20 and 28, after CBY-Aden issued third and fourth directives as part of its campaign to measure and inspect the compliance of dozens of financial transfer and money exchange companies operating in the sector. This resulted in the license suspension of two of the largest money exchange companies in the country: the first, Al-Akwa Exchange Company, is headquartered in Sana’a but covers territory in both Houthi- and government-controlled areas; the second, Al-Qutaibi Exchange Company, is headquartered in Aden and serves southern Yemen.

On October 18, CBY-Aden lifted suspensions on two exchange companies, Al-Mihdhar Company and Alhudna Company, after they agreed to abide by the money exchange law and CBY-Aden’s instructions.

Two days later, CBY-Aden warned Yemeni merchants and citizens against opening accounts or maintaining balances with all money exchangers to avoid the risk of having funds confiscated or frozen. In the announcement, CBY-Aden indicated that its Banking Supervision Sector would be commencing inspections and field visits to monitor money exchangers’ compliance. By law, the operations of money exchange companies and outlets are limited to buying and selling foreign exchange, as well as conducting financial transfers; they are not allowed legally to accept money deposits.

During the ongoing conflict, the financial services provided by money exchangers have expanded to include a number of offerings, such as credit provision, that are technically in violation of previous central bank legislation and the law regulating money exchange businesses. The expanded services are a reflection of the weakening of Yemen’s formal banking sector and the strengthening and increased importance of money exchangers, not least in terms of trade finance.

The October 20 announcement was followed by a separate directive issued three days later that called on CBY-Aden-licensed exchange companies and outlets to start networking their automated teller systems with CBY-Aden headquarters, granting the central bank the full authority to monitor the transaction data of money exchange companies.[4] CBY-Aden stated that connecting automated systems is one of the requirements for having their licenses renewed and warned that failing to do so could lead to the revocation of their licenses. Law No. 19 of 1995, regulating the work of money exchangers, grants the central bank the right at any time to request any data, records and statistics from licensed money exchangers, including periodic statements on their financial positions detailing the total foreign transfers sent and received as well as foreign exchange transactions.

On October 25, CBY-Aden issued another circular directed to exchange companies and outlets, prohibiting them from dealing with eight financial transfer networks. These included several prominent hawala networks, such as Al-Najm Network for Financial Transfers, Al-Imtiaz Network for Financial Transfers, Al-Akwa Remittance network, Al-Hitar Express Network for Fast Transfers, Al-Yabani Remittance Network, and Mal Express Network for Financial Transfers.

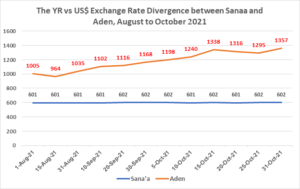

Local Currency Depreciation, Price Hikes Continue in Non-Houthi Areas

The price of goods and services continued to rise in non-Houthi areas during the last week of October in response to the depreciation of the Yemeni rial (YR). At the start of the month, October 2, the exchange rate was YR1,190 per US$1 in non-Houthi areas. The value of the rial continued to depreciate as the month progressed. On October 20, the exchange rate was YR1,325 per US$1,[5] and by October 28 it had reached YR1,330 per US$1.[6] The devaluation of the local currency and subsequent price hikes and worsening economic conditions fueled scenes of civil unrest in several governorates that fall under the administrative umbrella of the internationally recognized Yemeni government. These scenes were akin to those witnessed in August and September 2021.

Some of the major pricing developments that occurred during the last week of October, by governorate, included:

- Al-Mahra: On October 26, petrol was being sold at a rate of YR950 per liter/YR19,000 per 20 liters, up from YR610 per liter/YR12,000 per 20 liters at the end of August.[7]

- Hadramawt: On October 26, the Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) branch in Mukalla announced the resumption of the sale of petrol at YPC-run stations in coastal Hadramawt.[8] Prices were announced at YR850 per liter/YR17,000 per 20 liters for petrol and YR800 per liter/YR16,000 per 20 liters for diesel. The YPC Mukalla branch stated that the above prices would remain in place until an agreement was reached with traders who sell fuel to YPC Mukalla.

- Aden: On October 23, State owned-telecoms provider Aden Net announced increased internet tariffs due to local currency depreciation and the need to cover higher operating costs.[10] The following rates were set for different 30-day packages: YR3,000 for 20 GB, YR6,000 for 40 GB, YR9,000 for 60 GB, and YR12,000 for 80 GB.

Houthi-Run YPC Regulates Consumer Petrol Purchases

During the month of October, the Houthi-run part of the YPC started issuing daily lists of YPC stations in Houthi-controlled territories that would be selling petrol at the official price of YR8,500 for 20 liters.[11] The daily circulars began on October 11 and in addition to outlining the specific stations where petrol is to be available, different terms and conditions for consumers were also listed. Consumers were permitted to purchase up to 40 liters per vehicle within set time periods during the day. They were then not allowed to purchase any additional fuel for five days. The circulation of the YPC station lists seemingly began in parallel with the receipt of two different petrol shipments at Hudaydah port during the second week of October. These carried a combined total of 30,000 metric tons (MT) of fuel.

Features

How Outsiders Fighting for Marib are Reshaping the Governorate

Analysis by Casey Coombs and Salah Ali Salah

Marib governorate has emerged as a pivotal battleground between the armed Houthi movement on one hand, and the internationally recognized government and their respective allies on the other. The opposing forces are pressing with all of their might to achieve military victories in Marib, knowing that the outcome of the battle for the governorate holds the potential to decisively change the national balance of power.

In the early months of Yemen’s civil war, Marib emerged as a safe haven for internally displaced people (IDPs) fleeing Houthi-controlled areas. Marib’s small pre-war population of about 400,000 is estimated to have grown to between 1.5 million and 3 million people, with the bulk of the new arrivals settling in the capital, Marib city.[12] Amid this influx of IDPs, the internationally recognized government chose Marib as the headquarters for several departments in the Ministry of Defense, regional army commands formerly based in Houthi-held areas and training camps affiliated with these military units.[13] The Saudi-led coalition built army bases and installed Patriot missile defenses outside Marib city to protect oil infrastructure and support government forces, providing a security umbrella over the growing urban center, and thereby facilitating its growth.

After a four-year lull in fighting in Marib since late 2015, in January 2020, Houthi forces renewed their efforts to seize the governorate and have pursued this goal relentlessly. Since then, the frontlines in Marib have routinely been the bloodiest of the civil war.

The battle for Marib has attracted a growing number of military and security forces from outside the governorate. At the same time, political groups have sought to gain a foothold there. As part of broader strategies aimed at winning Marib, these outside actors have reshaped the local landscape in many ways, including through the installation or co-optation of tribal sheikhs who are more welcoming to their presence, and the appointment of loyalists in military, security and political institutions.

Identifying the most influential outside actors fighting for control of Marib and the strategies they are using to impose their will on the governorate is important to an understanding of how the socio-political landscape has changed during the war and what that means for the future.

While both Houthi and government forces have recruited Maribi locals to varying degrees, many of these individuals named to leadership positions do not wield as much power as their titles would indicate. Both warring parties have sought to highlight the presence of Marib locals on the frontlines and in decision-making roles to foster tribal and local legitimacy for their combat operations.[14]

After a brief overview of Marib’s pre-war indigenous population, this paper will identify the main military, security and political actors affiliated with the warring parties in Marib and describe how they are trying to reshape the governorate in their own image. The paper concludes by examining how Marib could change in the long term in the event of a decisive military victory by either of the warring parties.

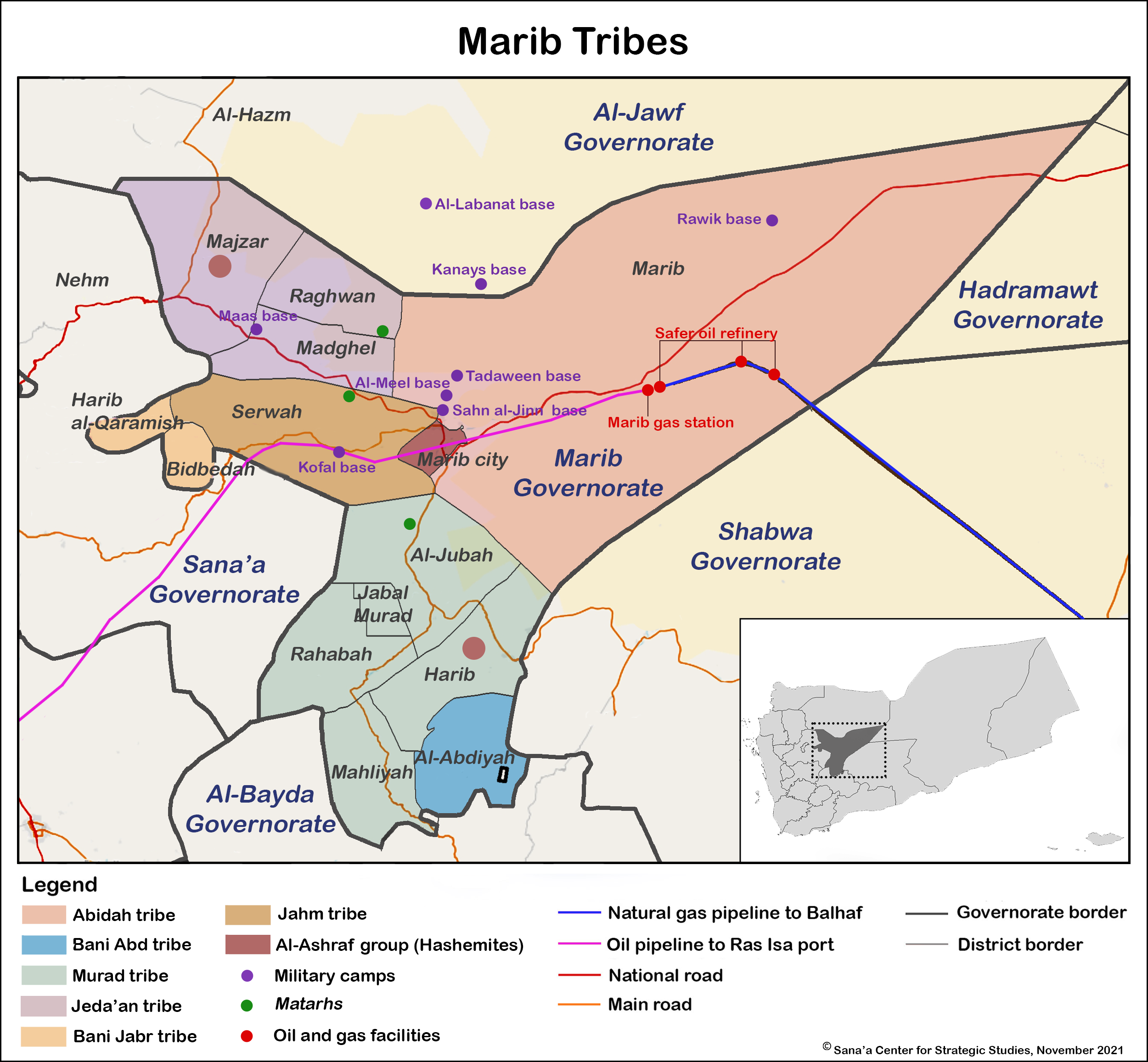

Marib’s Indigenous Population

Generally speaking, Marib’s indigenous population is composed of five tribal groupings – the Abidah, Murad, Al-Jadaan, Bani Jabr and Bani Abd – whose rules and customs regulate society, politics and economic life in the absence of an effective state. The two largest and most powerful tribes are the Abidah and Murad.

Abidah tribal lands cover the eastern half of the governorate, where oil and gas fields and infrastructure are concentrated. Marib’s governor, Sultan al-Aradah, is from the Abidah tribe. Although the capacity of local governance has greatly expanded under Al-Aradah’s leadership and eased the burden on tribes to perform the functions of the state, tribal identity remains strong.

The Murad, which is the largest tribe in Marib in terms of numbers, has the second-largest geographical footprint, predominantly located in five districts in southwest Marib: Rahabah, Al-Jubah, Jabal Murad, Mahliyah and Harib. In recent decades, Murad tribesmen enjoyed a strong presence in government and military leadership positions, owing to the greater access to formal education in their tribal areas, which stemmed from the tribe’s affiliation with the ruling General People’s Congress (GPC) political party of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Rather than invest in the development of a strong state presence in Marib, Saleh exercised influence in the governorate by co-opting influential tribal leaders to protect oil and gas pipelines and electric power lines, while rallying tribal fighters to weaken tribes that threatened the interests of the president. This tribal elite, which was for the most part affiliated with the GPC, benefited from the weakness of the state.[15]

In addition to Marib’s tribes, a network of families known as Al-Ashraf make up another important social group in the governorate. Concentrated in Marib city and in some parts of Harib and Majzar districts, the Al-Ashraf are Hashemites, or descendants of the Prophet Mohammed. Unlike the Zaidi Shia Hashemites prevalent in the Houthi-held highlands in northwest Yemen, the Al-Ashraf in Marib follow the Shafei branch of Sunni Islam. The vast majority of tribespeople in Marib are also Shafei Sunnis, while most of those in the neighboring highlands are Zaidi Shia. Historically, sectarian differences have not been a significant factor in conflicts between Marib’s inhabitants. Tribal disputes over land and access to resources have been a more common source of conflict.[16]

Government Military, Security and Political Forces in Marib

When Houthi forces seized the capital Sana’a in September 2014, Marib’s tribes formed a fighting force known as the ‘popular resistance’ in anticipation of Houthi incursions into the governorate. These resistance forces found a willing military partner in the internationally recognized government, which, after being driven out of Sana’a, quickly transformed Marib into its de facto capital in the north and military hub from which it could launch operations against the Houthis.

The Islah party, which has a great deal of influence in the internationally recognized government, also established Marib as a base after losing its presence in most northern governorates when the Houthis swept to power. The relative stability in Marib attracted a number of middle-ranking and lower-ranking Islah party leaders to the governorate.[17] As the war has dragged on, Marib has continued to be a destination for other Islah officials and supporters, such as those driven out of parts of southern governorates as the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) has consolidated control of Aden and surrounding areas.[18]

Although Islah had a presence in Marib before the war,[19] Saleh’s GPC party dominated the governorate’s political landscape. Support for the GPC, however, began to decrease across Marib after Saleh’s ouster in 2012 following Yemen’s 2011 Arab uprisings. This decline in support accelerated after Saleh allied with the Houthis to take over Sana’a in September 2014 and expand militarily across the country. In 2014, the Marib branch of the GPC, led by Murad tribal leaders Abdulwahid al-Qabli and his father, Ali Nimran al-Qabli, rejected a request from Saleh to remain neutral and not fight the Houthis.

The subsequent deaths of several prominent GPC leaders, including Saleh, who was killed by the Houthis in December 2017, have further eroded GPC support in Marib. Some of these former Saleh loyalists, such as Al-Qablis, established a GPC wing aligned with President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, while others shifted their support to the Islah party, which has used its powerful presence in the Hadi government and presence on the ground to capitalize on these shifting political winds. For example, Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, who is technically registered as a GPC member, but has long supported Islah, has been the top government official overseeing military operations in Marib since 2016. Saudi Arabia has also attempted to co-opt a number of senior GPC figures during the war.[20]

Marib’s Abidah tribe has, indeed, become a center of gravity of the Islah party during the war. Abidah areas historically voted for the GPC in parliamentary elections. A number of prominent Abidah tribesmen, including Governor Al-Aradah, who was formerly a member of the GPC Standing Committee and a Member of Parliament with the party, have gravitated toward Islah in recent years. This shift has been based more on pragmatism than ideology, as Islah has emerged as a dominant power in Marib with ample resources. These stem in large part from the party’s close relationship with the central government and Saudi Arabia.

While tribal identity remains stronger than party affiliation or other factors, the Islah party has been relatively successful in partnering with Marib locals. This alliance is primarily rooted in the common goal of preventing Houthi incursions into the governorate, but is strengthened by a shared adherence to Shafei Sunni Islam, which has a long history of opposition to inroads by the Zaidi Shia groups that ruled parts of northwest Yemen, on and off, over the last millennium.

However, Islah’s relations with Marib’s locals have been strained at times by the party’s appointment of unqualified loyalists to military, security and public administration positions. A frequent complaint from political leaders and social figures who are not affiliated with the Islah party is the presence of a large number of teachers affiliated with the group, who previously worked in public schools, Quran memorization schools or the education ministry, in civil and military institutions.[21]

Islah has directly supported Marib sheikhs who are perceived as loyalists at the expense of sheikhs aligned with other political parties, such as the GPC and the Yemeni Socialist and Nasserist parties.[22] Individuals from these parties also accuse Islah of installing loyalist military and security leaders from outside Marib over those from the local population.[23] Some GPC figures and sheikhs who were influential before the war, when Islah and the GPC were competing intensely in local and parliamentary elections, say they have since been marginalized.[24] Members of the Islah party have also gained a large presence in business and real estate activities in Marib city’s booming economy.[25] The party’s widespread influence within the governorate has led many Marib residents to engage with Islah on a pragmatic basis in order to advance their own interests.[26]

As the governor and one of the Abidah tribe’s most respected leaders, Al-Aradah has played a crucial role in managing relations between Marib’s indigenous population and power brokers like the Islah party, as the governorate grew into a major government stronghold during the war.[27] Al-Aradah was selected as the ultimate arbitrator of tribal disputes on September 18, 2014,[28] when Marib’s tribes agreed to postpone feuds in order to focus on protecting the governorate from Houthi advances. They agreed that Al-Aradah, in his capacity as an Abidah tribal sheikh and Marib governor, would mediate any future disputes. The agreement helped define the balance of power between the governorate’s tribes and the state, in this case mostly meaning the Islah party.[29]

Houthi Forces in Marib

The majority of Houthi commanders overseeing the Marib fighting hail from the group’s northern stronghold in Sa’ada governorate along the Saudi border. Most of these commanders fought during the six Sa’ada wars between 2004 and 2010 in which Houthi forces variously battled army forces loyal to Saleh, and military units loyal to General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar. Some of the most senior Houthi commanders in the Marib campaign are related to Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi. These include his brother, Abdelkhaleq al-Houthi (Abu Younes),[30] commander of the Central Military Region, which includes Marib. Yusuf al-Madani,[31] who leads Houthi forces in Hudaydah, Hajjah, Mahwit and Raymah governorates as commander of the Fifth Military Region, was recently assigned to the offensive in Marib. He is married to one of the daughters of the Houthi founder, Hussein Badreddine al-Houthi, another brother of Abdelmalek. The Houthis’ security supervisor in Marib also hails from Sa’ada. Only a handful of Houthi military and security leaders in Marib are from the governorate, such as Mubarak al-Mishn al-Zayadi, commander of the Third Military Region, which covers Marib and Shabwa governorates.[32] However, Al-Zayadi’s duties are limited to formal inspection visits, meaning that in practice, he does not exercise substantial influence.[33] The power is thus concentrated in the hands of Houthi leaders from outside the governorate, such as Abdelkhaleq al-Houthi and Yusuf al-Madani.

Most of the rank-and-file Houthi forces fighting in Marib come from Amran, Sana’a and Dhamar governorates.[34] The small numbers of Houthi forces from Marib are mainly from the Hashemite Al-Ashraf group or the Zaidi minority of the Bani Jabr tribe and its Jahm subtribe in Harib al-Qaramish district.[35] In addition, a few figures from the Murad tribe, such as the prominent sheikh, Hussein Hazeb, along with a few other minor tribal leaders, sided with the Houthis for political and other reasons unrelated to religion.[36]

The Houthis have struggled to recruit Marib locals to their cause for a number of reasons. The vast majority of people in Marib follow the Shafei branch of Sunni Islam, including the Al-Ashraf group. The Houthis’ divisive sectarian rhetoric during the war has exacerbated distrust between Shafei and Zaidi communities. From a tribal perspective, Marib locals have cited the Houthis’ double-dealings with the tribes that facilitated their entry into areas in Amran, Hajjah, Sana’a and other Houthi-controlled governorates as evidence that the group does not respect tribal norms and cannot be trusted. Indeed, the Houthis regard tribes as inferior to the Hashemite sayyid class to which the Houthi family belongs. The Houthis, like the Zaidi Hashemite dynasties that ruled parts of Yemen on and off for a millennium, have strategically manipulated tribal norms in order to gain religious and political legitimacy, while also relying on the tribes to supply fighters.[37]

There are also deep historical rifts between populations in Marib and Sa’ada governorate, which is a traditional Zaidi stronghold and the Houthi movement’s homeland. Starting in the 1930s, Marib’s two dominant tribes, Abidah and Murad, fought back military incursions by the Zaidi imams of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen. In 1948, Sheikh Ali Nasser al-Qardae’i, one of the most prominent sheikhs of the Murad tribe, assassinated Imam Yahya Hamid el-Din, ruler of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom. It is widely believed in Marib that the Houthis seek to build a theocratic state modeled on the Zaidi imamates that were first based in Sa’ada, and later controlled larger areas of northern Yemen.[38]

Changing Tribal Dynamics

Like Saleh before them, Houthi and government forces have tried to coerce and co-opt local tribal leaders to control Marib. The warring parties have recruited a new class of sheikhs who are more welcoming of their presence and objectives. This has led to a rebalancing of tribal power in the governorate reminiscent of former President Saleh’s patronage politics.

Throughout the war, the Houthis have sought to empower loyalist sheikhs in areas where the group has geographical and cultural ties with local tribes.[39] The Houthi movement used this tactic in its six wars against the Saleh regime between 2004 and 2010, and has subsequently relied on it to consolidate power when it started expanding beyond Sa’ada governorate in 2011. Houthi inroads into other parts of Yemen greatly benefited from the group’s alliance with Saleh, whose tribal loyalists facilitated Houthi advances that culminated in the takeover of Sana’a in September 2014.

The Islah-dominated internationally recognized government has used similar tactics in Marib during the war. Some sheikhs affiliated with the GPC who benefitted from Saleh’s patronage system have been neglected, or their powers reduced, as resources have been diverted to new sheikhs.[40] Often, the newly-favored sheikhs work alongside the traditional sheikhs, but with financial and official support, their authority becomes dominant over time.

Conclusion: What’s Holding Marib Together? How Long Will it Last?

The outcomes of the battle for Marib will change many of the parameters of the current political equation, whether in the event of a forcible Houthi takeover of the governorate, or if government forces stem recent Houthi advances – or even if an accommodation is reached.

As the internationally recognized government’s last stronghold in northern Yemen and a source of abundant oil and gas reserves, Marib is a strategic and highly prized governorate in the war between the Houthis and the government.

Marib is also unique in that the diverse grouping of anti-Houthi forces there have not turned on each other, as witnessed in other major cities in non-Houthi controlled areas, such as Aden[41] and Taiz.[42] This is largely due to the fact they have set aside differences to focus on the urgent need to fight the common Houthi enemy. Another factor is Marib’s relative economic prosperity in recent years, which has helped diminish a key source of grievances in other governorates nominally controlled by the internationally recognized government. However, the growing power of the Islah party has strained these relations.

The outsize role of Al-Aradah in managing relations between local tribes and outside forces cannot be overstated; if something were to happen to the governor, the stability of Marib would be at great risk. Since the UAE removed its Patriot missile defense system from Marib in 2019, the Houthis have launched missile strikes numerous times against his homes – including his official residence in a government complex – most recently on September 26.[43] If the Houthi offensive is neutralized and the common enemy uniting Marib’s anti-Houthi alliance fades away, existing tribal feuds and tensions from new imbalances in power may emerge, if figures with the standing and respect of Al-Aradah are not in power to address them.

Rapid Houthi military advances in Marib’s southern Al-Abdiyah, Harib, Al-Jubah and Jabal Murad districts since late September have also now created a potential opening for them to attack Marib city from the south. A Houthi victory in Marib would usher in profound tribal, religious and cultural changes. As has occurred in other Houthi-controlled governorates, the group would appoint loyalists as supervisors (mushrifeen)[44] and to other key positions of power. New religious leaders, promoting an extreme version of Zaidi Shiism, would also be appointed. Indeed, after Houthi forces seized control of Harib district in Marib and Bayhan district in Shabwa in September 2021, the group immediately replaced the imams of mosques in these areas with extremist loyalists from Sana’a, Amran and Sa’ada governorates and started preaching in schools.[45] One of the major roles of the religious leaders is to conduct cultural lectures and summer camps aimed at indoctrinating children and other populations in Houthi-held areas.[46]

In the event of a Houthi takeover, Marib tribes, for their part, would likely resume sabotaging power lines leading to Sana’a, as they did at various times prior to the war as a means of leverage over the Saleh and Hadi governments. However, the tribes do not consider the Houthis to be a legitimate government and would likely not attack the pipelines simply as a tool for concessions, but more likely as part of an insurgency and a tactic to weaken Houthi power.

Even in the event of a Houthi takeover of Marib, the victory could therefore be pyrrhic. Local tribesmen share a deep cultural memory that considers Zaidi Hashemite groups like the Houthis to be outsiders seeking to dominate and subjugate them, rather than incorporate them into the ruling system.

Casey Coombs is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and an independent journalist focused on Yemen. He tweets @Macoombs

Salah Ali Salah is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

This analysis was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies as part of the Leveraging Innovative Technology for Ceasefire Monitoring, Civilian Protection and Accountability in Yemen project. It is funded by the German Federal Government, the Government of Canada and the European Union.

Forgotten War, Abandoned Refugees: The Plight of Yemenis in Lebanon

By Ali al-Dailami

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published at Public Source.)

When Saad was told by an employee at an office of UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, that the resettlement option was not available to Yemeni applicants in Lebanon, he felt devastated.[47] His thoughts went immediately to his aging mother in Yemen, who had squeezed every last drop of her savings to pay for her son’s ticket to Lebanon — a destination they saw as their last chance for a future away from violence and starvation.

Why wasn’t the resettlement option available to Yemenis, like it was to Syrian refugees, wondered Saad?

Yemen, one of the poorest countries in the world, is now in its seventh year of a brutal war that the UN has deemed “the worst humanitarian crisis in the world.” More than 4 million Yemenis have been driven from their homes.

Lebanon is one of a few remaining countries Yemenis can enter without onerous visa restrictions. While they still need a visa, they can obtain a three-month-long tourist one upon arrival at the Beirut airport — as long as they are carrying $2,000 in cash and proof of a hotel booking.

Before the start of the war in 2015, Yemenis were frequent visitors to Lebanon. They came for medical treatment, on business, as students and tourists.

Today, as life in Lebanon has become extremely difficult for most of its residents, Yemenis face compounded challenges: trying to survive economically while navigating a procedural labyrinth for refugee status that leaves them in limbo and uncertainty.

Daily Life for Yemenis in Lebanon

For the average Yemeni in Lebanon, navigating a cost of living that is 55 percent higher and rent that is 276 percent higher than in Yemen is no easy feat — especially when they cannot legally work. The Lebanese Labor Act bars any visiting foreigner from work except for those with a work permit issued by the Lebanese Ministry of Labor, which requires applicants to meet conditions that are very difficult to fulfill. For example, one condition is that prospective migrants receive pre-approval from the ministry before arrival in Lebanon. Fearing imprisonment and deportation, Yemenis stay away from work in Lebanon.

Students, who make up the majority of the Yemeni community in Lebanon, face the biggest hurdles. Some of them relied on scholarships and a regular stipend from the Yemeni government before the war, but now continuous delays in payments have had many of them go hungry or be kicked out of dorm rooms when they couldn’t pay rent.

Although students protested these conditions in front of the Yemeni Embassy in Beirut in 2016, their acts were not picked up by Lebanese or international media, and the situation has not improved.

Those students without scholarships relied on their families in Yemen for financial support, but six years of war has almost depleted this source.

Even renewing their residency permit, which the Lebanese state requires be done annually, is a source of stress for students. Costing around 300,000 L.L., the renewal process requires identification papers, proof of a foreign source of income, a certificate by an institution or university that specifies the enrollment period, proof of domicile in Lebanon, and an attestation signed by a notary that the student will not work.

“It is frustrating. I no longer know whether I should focus on my studies, or on how to spend the little money I have to survive for as long as possible,” confessed Sam, a Yemeni student who came to Lebanon in 2013 to attend university.

Forced to choose between hunger or an education, dozens of Yemeni students have dropped out of school.

Yet, many Yemenis do find life in Lebanon personally enriching and enjoy the eye-opening exposure to multiple cultures, rich history, different languages and lifestyles. Personal freedoms are also crucial: Yemenis can move freely around the country, provided they carry their visa or residency permit, and they are not concerned about any direct religious oppression.

Becoming a Yemeni Refugee

According to UNHCR figures, only 25 Yemenis in Lebanon counted as refugees in mid-2020.

Under the 1951 Refugee Convention definition used by UNCHR, a refugee is an individual who “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or owing to such fear is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

To apply for refugee status, Yemenis first fill out a form at the UNHCR office in Lebanon, and then await an interview with an official. For the interview, the applicant should bring supporting certificates and documentation. At the interview, questions revolve around the applicant’s background, health status, family status, future plans, political issues, life in Lebanon and the way an individual is coping with it. Next, the office checks the legal status of the applicant and whether or not their yearly residence permit has expired. The office also checks if the applicant has a criminal history with the Lebanese General Security.

Pending refugee status, UNCHR deems an applicant an “asylum-seeker,” or “an individual who has sought international protection and whose claims for refugee status have not yet been determined.”

In 2020, there were 104 Yemeni asylum-seekers in Lebanon.

According to UNHCR statistics, between 2017 and 2019, the number of Yemeni asylum-seeker applications in Lebanon decreased from 50 to 29. Out of a total 121 asylum applications in this period, 40 were approved. It is unclear why 81 were “otherwise closed” by UNHCR.

UNHCR also provides resettlement options, in which refugees request to migrate to a third state that has agreed to admit them and grant permanent residence. This mandated solution is intended for refugees who cannot return home because of continued instability, wars, or persecution.

As the war in Yemen is ongoing, with widespread poverty, famine, fear and destruction throughout the country, Yemenis abroad cannot return.

“I applied because I saw no future left for Yemen. I, and later my family, wanted to be recognized as UNHCR refugees and be resettled in another country that has a better life,” said Yaser, a Yemeni man who moved to Lebanon with his wife and children to pursue his studies

Yet becoming a UNHCR-approved refugee is its own arduous journey.

Interviews conducted in May 2021 with 14 Yemeni men and women who had applied for refugee status at the UNHCR offices in Lebanon revealed a joint sentiment that the resettlement process takes too much time and that they do not have hopes of their applications being accepted, with some describing the whole process as “fruitless.”

“After being done with the interview, once accepted, we were given a UNHCR asylum-seeker certificate. This means we have not yet been granted the refugee certificate, even if getting to this stage of the application process took over a year,” said a Yemeni man who had applied with his family three years ago.

Interviewees also believe that UNHCR treats Yemeni applicants differently than applicants from other nationalities.

“Unlike other nationalities, Yemeni applications take a very long time, even though the number of Yemeni applications is tiny compared to others. I am losing faith in the UNHCR,” one Yemeni asylum seeker said.

Another asylum-seeker recalled what one UNHCR employee said to him: “You don’t have a Yemeni government that would bring our attention to its scattered citizens. No comparison can be made between the millions of Syrians who left their country and are staying in Lebanon, and the Yemenis whose numbers are negligible.”

Recently, a few Yemenis have been accepted to be resettled and granted refugee certificates by the UNHCR, but their resettlement process is still pending. When speaking to these applicants, it seemed that at least two were actively supported by a UN official and a member in the UN panel of experts in Yemen.

The research for this article found that only one Yemeni refugee had been successfully resettled in Europe — and that his case was connected to a senior politician wanted by a warring party in Yemen.

Average Yemenis who cannot appeal to political influence seem to not progress through the internal processing at the UNHCR office.

The reasons behind this remain unclear, and UNHCR did not respond to the author’s request for comment at the time of this writing.

“When I told a UNHCR employee that it was my right to become a UNHCR refugee and be resettled,” recalled Saad, “she replied: ‘We do not grant Yemeni applicants the resettlement solution.’”

Another asylum-seeker put it bluntly: “I realized that on paper, I am told that I could become a refugee and be resettled, but in the reality of this world, I totally couldn’t.”

The Limits of UNHCR Assistance

Yemeni asylum-seekers expressed frustration that the UNHCR does not help them navigate complications with Lebanese state institutions.

Such is the case with arrests and deportations of Yemenis who hold asylum-seeker status.

According to procedure, a Yemeni individual with a UNHCR asylum-seeker certificate must carry it with them at all times. In case of arrest by Lebanese General Security officials for an expired residency permit, the asylum-seeker must call the UNHCR office, which is supposed to assign them a lawyer to work for their release.

Yet this process did not work for Adam, who held asylee status from the UNHCR office when he received a deportation notice in 2016 issued by Lebanese General Security as his residency permit expired. Adam alleges he did not receive any attention from the UNHCR and had to eventually ask Lebanese friends for help.

The threat of deportation afflicts Yemenis beyond Lebanon. In Jordan, deportations this year led to an outcry among the Yemeni diaspora and human rights organizations against deportations of Yemeni asylum-seekers registered with UNHCR.

Most of the interviewees affirmed they received financial and humanitarian aid from the UNHCR office.

“I received $280 per month from the UN for about six months, and then it stopped a few years ago. When I asked why, I was told that monthly financial aid is given based on priority and for a limited period of time,” a Yemeni applicant stated.

Another applicant recounted: “The office gave me 40,500 L.L. per month for a while before it stopped…that was when the exchange rate of a US dollar was 1,500 L.L. Once I got the certificate, the monthly support lasted for only three additional months. The following year the aid increased to 100,000 L.L., after the change in currency exchange rates, but continued for only four months. This year, I have yet to receive anything.”

The UNHCR office also offered an annual one-time winter aid. In January, one asylum-seeker received 900,000 L.L. Last year, as the exchange rate differed, he received 400,000 L.L.

Finding their lives in limbo, and amidst confusion about the timing and amounts of financial assistance from UNHCR, Yemenis feel they are treated as passive, short-term aid receivers.

Forgotten War, Forgotten Refugees

Amidst what is practically a media blackout on the devastating conditions inside their country — and in the absence of powerful advocacy campaigns by Yemeni civil society and human rights activists — Yemeni refugees feel that their fate, like that of their home, is not a priority for the international community.

Every year, a limited number of submissions by the UNHCR are considered for refugee resettlement programs. Those programs are usually established and determined by resettlement countries.

Some of these countries are also involved in the war in Yemen or are complicit with the war crimes and perpetuate the war through massive arms deals, the United States of America, the United Kingdom, France, Canada, among others.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a UN source familiar with the matter stated, “Unfortunately, Yemenis are not listed by the prominent countries. Those countries control the scene of resettlement, and politics play a big role in that. Yemen is considered a problem by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. See, Syria exerted a big pressure on Europe by the flows of refugees from Turkey but Yemen is not a close problem to such countries. The latter would always work on the problems that are internally affecting them.”

By comparison, Lebanon and Yemen host more migrants than many of the world’s wealthiest states.

In 2018, Yemen received more migrants than all of Europe. In 2019, 11,500 people on average boarded vessels each month from the Horn of Africa to Yemen, making the Red Sea the busiest maritime migration route on earth — though it receives almost no attention in comparison with the Mediterranean. Yemen also hosts the second-largest number of Somali refugees in the world.

Lebanon has also placed more powerful and wealthy states to shame by opening its doors to millions of refugees from around the world, even though it is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol.

Amidst Lebanon’s financial and economic crisis, UN agencies and international advocacy organizations must do more to assist and support Yemenis within the country and abroad.

Ali al-Dailami is a researcher and program manager at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

Book Excerpt: The Day the Gunmen Came

By Abdulkader al-Guneid

(Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from Abdulkader al-Guneid’s book ‘Prison Time in Sana’a’, published in September by Arabian Publishing.)

The gunmen came for me at 3:00 in the afternoon. When they drove me away an hour later, I didn’t know if I would ever see my home again.

It was August 5, 2015, and I was being abducted from the home my wife Salwa and I had built together – the home where we had celebrated my 66th birthday just three days previously.

After a short drive, I was taken from the car and led – handcuffed and blindfolded – into a building. I was made to stand facing a wall. And then my interrogation began. It would continue for five exhausting hours.

Two men questioned me. By their accents, one was from Taiz and the other was from the north. I asked which branch of the security forces they were from, and the northerner claimed they were merely ‘God’s supporters’.

(Editor’s Note: Ansar Allah, Supporters of God, is the official name for the armed Houthi movement.)

Later they passed me on to another man, Mohammed al-Sharafi, who searched my pockets and demanded my identity card. I explained that I didn’t have it with me, having been kidnapped from my own home with no chance to bring anything. “Yes, you were innocently doing nothing. They just took you like this, for no reason,” he mocked. Then, rather more threateningly, he growled: “You are ISIS”.

I couldn’t contain myself and laughed: “Not that again!”

He reappraised me scornfully, drawing out every syllable: “Mog-aaaaaa-wameh” (Resistance).

I smiled to myself grimly as Al-Sharafi blindfolded me and bundled me inside the building. Now I had become one of the ‘forcibly disappeared’, vanishing into the Houthi-occupied capital. I was manhandled along a high-ceilinged, cold corridor, which I could occasionally glimpse below my blindfold. It was expensively tiled, carpeted in the middle and with luxurious wooden doorways leading off it – an Ottoman-era building repaired and refurbished by President Ordogan to revive the Turkish legacy in Yemen.

Before I was given a space on the floor to sleep, I asked to use the bathroom, and Al-Sharifi grudgingly released one hand from the cuffs, led me to the facilities and warned me not to “do anything heroic.” I was then ordered down onto the red carpet and told to sleep, having been refused a blanket. Despite the chill, I felt the tension seep from my tired body and was quickly overcome with sleep. Shortly afterwards, though, I was awoken by someone having difficulty breathing and I realized I wasn’t alone.

Someone moved toward the struggling man and was rudely ordered back to his spot.

“I have to help him,” a voice replied. “He’s my brother. He’s sick and just had an operation on his chest in Jordan.”

Soon, however, the man’s tortured breathing eased, and he seemed to fall asleep – as did I. When I next awoke, I could see the morning light coming from the end of the corridor. It was eerily quiet.

“Is there anyone around?” I called out. “I need the bathroom.”

There had been a change of guards and a new one led me to the end of the corridor and unshackled my right wrist. I went inside and undid the blindfold. From the window, I caught a glimpse of the top of one of the city’s characteristic old buildings, confirming that I really was in the 200-year-old building that had been taken over by the security services and used first by Saleh and later by the Houthis as an interrogation and internment center.

I put my blindfold back on and came out, but I could still make out a masked and khaki-clad soldier with a Kalashnikov on his shoulder. He placed my handcuffs, tightened the blindfold and then led me back to my place, where I was ordered to lie down.

A considerable time later, I was given a small breakfast of bread and beans, which I ate hastily while still bound and blindfolded. It was the first food I had eaten in almost 24 hours. Around me, I could glimpse several other prisoners. We were not allowed to sit, stand or speak, being instructed to “lie down and keep your mouths shut”.

Later came a simple lunch of rice, potatoes and a small piece of meat. I ate with reluctance. The silence was total and, due to the blindfold and my ordeal the previous night, I dozed intermittently until the evening – which was when my interrogation began.

Darkness had descended and it was quiet and still when I heard heavy footsteps along the corridor, the buzz of voices and the banging of doors. By now there were more people sitting along the corridor. I remained handcuffed on the carpet in the middle, peeking from behind the blindfold. I could hear people being questioned beyond the closed doors. Soon, I was ordered to my feet and taken into one of the rooms.

Glancing from under my blindfold I could see three men sitting Yemeni-style on a carpet-covered mattress, their arms resting on rectangular bolsters. Their leader was dressed in a pressed white thobe, over which he wore a tailored dark waistcoat. He turned his head aside as I entered the room, wary that I might be able to see his face. I was ordered to sit on a battered sofa, from where I could make out someone on a chair in front of me dressed in a ma’awaz – similar to a long Scottish kilt. From his accent I could tell he was from my home region.

Sitting next to the leader was the one asking the questions, though he clearly wasn’t the one directing the interrogation. In the middle of some questions, he would suddenly halt and then ask something out of context. Whenever he stopped in the middle of a sentence, it was as if someone was signaling him not to proceed or not to press me so hard. The real bosses were in the background, unseen and unspeaking.