Members of the Security Belt forces stand at attention in Aden 15 minutes before dozens were killed in an attack on their military ceremony on August 1, 2019 // Photo Credit: Rajeh Al-O’mary

The Sana’a Center Editorial

The March on Al-Mahra

The reasons the Yemen War began are fundamentally different from why it continues today. All parties to the war – local, regional, and international – have exploited the chaos and collapse of the state to pursue their own vested interests. Among these: powerful actors in the armed Houthi movement have accrued vast sums of wealth through aid diversion and exploiting their control over imports into northern areas, particularly fuel. The Islah Party, which opposes the Houthis, has sought to establish fiefdoms of power in Taiz City and Marib governorate. Southern separatist groups are seeking to fracture the country in two and reestablish an independent South Yemen; in this pursuit they are backed politically, financially and militarily by the United Arab Emirates, which has regularly undermined the internationally recognized Yemeni government even while fighting on its behalf. Meanwhile, Iran has been able to heavily antagonize its arch-nemesis, Saudi Arabia, through providing the armed Houthi movement with political and financial support and military expertise, such as sophisticated drones and weapons capacities.

The reasons the Yemen War began are fundamentally different from why it continues today. All parties to the war – local, regional, and international – have exploited the chaos and collapse of the state to pursue their own vested interests. Among these: powerful actors in the armed Houthi movement have accrued vast sums of wealth through aid diversion and exploiting their control over imports into northern areas, particularly fuel. The Islah Party, which opposes the Houthis, has sought to establish fiefdoms of power in Taiz City and Marib governorate. Southern separatist groups are seeking to fracture the country in two and reestablish an independent South Yemen; in this pursuit they are backed politically, financially and militarily by the United Arab Emirates, which has regularly undermined the internationally recognized Yemeni government even while fighting on its behalf. Meanwhile, Iran has been able to heavily antagonize its arch-nemesis, Saudi Arabia, through providing the armed Houthi movement with political and financial support and military expertise, such as sophisticated drones and weapons capacities.

Al-Mahra, Yemen’s most easterly and isolated governorate along the Omani border, has become a new epicenter for vested geopolitical interests, as recently published Sana’a Center research has shown.[1] Being many hundreds of kilometers from the nearest frontline, the governorate has been under no threat from Houthi offensives during the ongoing conflict. Despite this, Saudi attack helicopters have carried out airstrikes against local tribal checkpoint this year. Since 2017, Saudi forces have taken control of and converted the governorate’s main airport in the capital, Al-Ghaydah, into a military complex, seized control over ports and border crossings, established almost two dozen military bases, and recruited both locals and Yemenis from other governorates into paramilitary and proxy-security forces. The Saudi military expansion in Al-Mahra has spurred a growing popular opposition movement with frequent local protests. These have at times been violently broken up and devolved into gunfire. Protest leaders, civil society activists and journalists have also been threatened and arrested.

Riyadh originally justified its military push into Al-Mahra as necessary to counter arms smuggling through the governorate to Houthi forces farther west, and since then the Saudi presence has taken on the tone of counterterrorism. Indeed, Saudi troops and their proxies seem to be doing a degree of both – as evidenced by Saudi special forces arresting the leader of the so-called Islamic State group, or Daesh, in Al-Ghaydah in June this year. However, the intensity of the Saudi effort to exert security and military control in Al-Mahra seems to suggest broader ambitions in the governorate.

Neighboring Oman, which has kept a relatively neutral image thus far in the wider Yemen conflict, has also been trying to safeguard its interests in Al-Mahra. Oman has long viewed Al-Mahra as key to its security and opposes Riyadh’s encroachment in what Muscat considers its historical sphere of influence. Omani officials are politically and financially supporting the Mahri protest movement, and at times have turned a blind eye to smuggling across the border. Muscat plays host to prominent figures who are publicly critical of the Saudi and Emirati-led military coalition intervening in Yemen, while also building a web of influence beyond Mahra, funding actors in other southern governorates. Doha also appears to have its hands in Al-Mahra, sponsoring and providing a media platform for anti-coalition figures. Notably, a Qatari intelligence officer was arrested at a border crossing with Oman in May 2018. Emirati attempts to assert influence in the governorate early in the Yemen War were rebuffed by local opposition, following which Abu Dhabi’s attention shifted to establishing military dominance on the island of Socotra, which has strong historical and cultural ties to Al-Mahra.

The internationally recognized Yemeni government – though ostensibly backed in its fight against the Houthis by the Saudi and Emirati-led military coalition – has often been at odds with the UAE and protested the Emirati moves in Socotra all the way to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). The Yemeni government, which is largely based in Riyadh and is almost completely beholden to Saudi Arabia for its continued existence, even felt compelled recently to break its silence on the Saudi military expansion Al-Mahra: “The Yemeni government wanted our allies in the coalition to march with us north, not east,” Yemeni Interior Minister Ahmed al-Misri said in May this year.

The geopolitical power struggle underway in Al-Mahra is reckless, in that it is destabilizing one of the few places in Yemen that has been untouched by the primary conflict. UNSC Resolution 2216 of April 2015 condemned the Houthi seizure of Sana’a, called for the Yemeni government’s reinstatement to power, and noted that the government had requested Gulf countries assist in this regard. The Saudi and Emirati-led coalition have since used the document as legal legitimacy for military intervention in Yemen. Prolonged foreign military intervention inevitably brings about shifts in the interests, agendas, allies and actions of the interveners. However, in the case of Yemen, coalition member states have drifted far outside the word and spirit of Resolution 2216, meaning it is highly likely their pursuits of political and military control far from the frontlines are illegal under international law.

Contents

Developments in Yemen

- Military and Security Developments

- Economic Developments

- In Focus: Houthi Authorities Sentence 30 Detainees to Death

- Humanitarian Developments

International Developments

- Iran and Rising Regional Tensions

- At the United Nations

- In the United States

- In Europe

- Other International Developments

- Endnotes

Developments in Yemen

Military and Security Developments

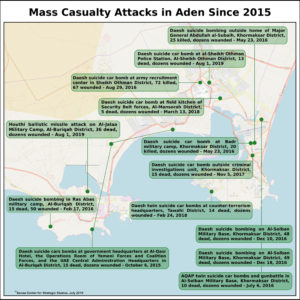

An Interim Capital of Carnage

The pervasive insecurity of the internationally recognized Yemeni government’s interim capital of Aden was on gruesome display August 1, when a pair of attacks – a Houthi-claimed missile or drone strike on a military parade, and an Islamic State suicide bombing near a police station – killed at least 49 people, including a powerful military commander.

At roughly 8 a.m., a suicide bomber blew up an explosives-packed vehicle just outside the gates of the Sheikh Othman police station, killing 13 police officers, in an attack claimed by Islamic State militants who said the attack targeted security forces in league with the Emirati government.[2] An hour later, a missile or drone struck a graduation ceremony at Al-Jalaa military camp in Buraiqa, in western Aden, where UAE-allied Yemeni forces are based, killing Brig. Gen. Muneer al-Mashali, better known as Abu al-Yamama, and 35 other soldiers. The Interior Ministry provided the casualty figures,[3] and witnesses to the attacks noted there were many injured, several seriously. The Yemeni government and coalition member states quickly condemned the attacks, which Prime Minister Maeen Abdul Malik claimed were coordinated and directed by Iran.[4]

The armed Houthi movement claimed the attack on the military camp, with spokesman Yahya Sarea saying the group had launched a Qasef-2K drone and a medium-range ballistic missile.[5] However, multiple witnesses who spoke to the Sana’a Center reported hearing only one explosion, and there was only one impact crater at the scene. Witnesses also reported seeing a drone overhead minutes after the explosion, which then left the area without further incident. A senior military official told the Sana’a Center that Aden’s Patriot surface-to-air missile system, capable of intercepting incoming missiles, was turned on but in “sleep mode”. He did not say why. Another security source, speaking about the suicide bombing at the police station, said the Political Intelligence Department had issued a report three days earlier warning that bomb-laden cars were being sent into Aden. There were no visible signs of increased security ahead of the blast.

Witnesses attending the ceremony told the Sana’a Center that Abu al-Yamama had stood up from his chair during the ceremony and walked to the back of the stage, possibly taking a phone call, when the strike occurred some meters behind the stage. The soldiers killed were in the back area. Video circulating online showed hundreds of soldiers marching in place to a military drumbeat; the marching and drumming paused and senior officers sat chatting quietly on the stage when a loud explosion sent grey smoke billowing behind the stage and soldiers running.

Following the attacks, public rage against northern Yemenis surged and reports came from across Aden of northerners being rounded up and driven out of the city in buses, and northern-owned businesses being vandalized. Security Belt forces also established checkpoints at the entrances of the city to prevent northerners from entering.

Abu al-Yamama was the powerful Aden-area commander of the Emirati-backed al-Hizam al-Amni, or “Security Belt” forces. He was known as stolidly loyal to the UAE and as a strong voice for southern independence. He was also influential in his nearby home region of Yafea, Lahj governorate, where many residents have joined up with southern security forces backed by the Emiratis. Beyond being loyal to the UAE, Abu al-Yamama gained prominence as an effective fighter on the frontlines in Mansoura and Lahj. Still, Abu al-Yamama’s death isn’t likely to have a significant impact militarily, his position being primarily a security rather than frontline post, and one for which there are other capable officers available to step up.

Emirati forces have worked with and trained local soldiers and militias in southern Yemen. The UAE drawdown, which came to public attention in June, took the international community by surprise. Coalition intervention in 2015 – led by Saudi Arabia in the air and the UAE on the ground alongside local militias and parts of the former Yemeni military – altered the course of the war, stopping the armed Houthi movement’s rapid advance from north to south. Fighting continues, though territorial control has been relatively stable since 2016, except for a coalition-backed advance along Yemen’s west coast to Hudaydah City.

Only 10 days prior to the attacks in Aden, a senior UAE official described the troop drawdown in southern Yemen as a shift from a “military-first” strategy to a “peace-first” plan, but one that would not create a security vacuum because highly capable Yemeni forces would continue to receive support from the Saudi-led coalition.

Anwar Gargash, the UAE minister of state for foreign affairs, urged in a July 22 Washington Post commentary the international community prevent any side from exploiting or undermining the Emirati decision. Gargash said the UAE would continue to advise and assist local Yemeni forces and “will respond to attacks against the coalition and against neighboring states.”

Operational Changes Expected Following UAE Drawdown in Yemen

Coalition spokesman Colonel Turki al-Malki said the UAE along with other coalition members states remain committed to the restoration of the Hadi government, and a senior Emirati official said the redeployment decision had been fully coordinated with Riyadh.[6]

The Emirati military played a central role in anti-Houthi operations on Yemen’s west coast, including last year’s Hudaydah offensive. This involved training and coordinating between local and southern Yemeni troops who did the frontline fighting, and providing air cover. The Emirati redeployment from Hudaydah followed extensive dialogue within the coalition, “and we agreed with Saudi Arabia on the strategy of the next phase in Yemen,” Gargash, the Emirati junior foreign minister, tweeted Aug. 2.

A new joint command comprised of the heads of these Yemeni groups will centralize leadership of anti-Houthi military operations on the west coast under the command of Maj. Gen. Saghir Hamoud Aziz.[7] Aziz has been the top Yemeni government representative on the UN-backed Redeployment Coordination Committee (RCC) and was a senior figure in the Republican Guard during the rule of Ali Abdullah Saleh. Abu Zarah al-Mahrmi, the head of the Giants brigade – the largest troop contingent on the west coast number some 20,000 fighter – has thus far refused to participate in the joint command center, according to Sana’a Center sources at the joint command center.

Despite reports that Saudi troops have arrived at vacated bases on the Red Sea Coast, Sana’a Center sources say that these personnel were largely already present prior to the UAE drawdown.[8] Yemeni news outlets also reported the withdrawal of Sudanese troops from positions in Hays, Dahrami and Al-Tahita in Hudaydah governorate.[9] [10] General Abdul Fattah al-Burhan, Chairman of Sudan’s Transitional Military Council, said in a television interview on July 30 that no withdrawal was taking place and that Sudanese forces would remain in Yemen.[11] Military sources and senior Yemeni government officials told the Sana’a Center that these redeployments were made in preparation for a full Sudanese withdraw from Yemen by the end of the year. Though no exact numbers are publicly available, Sudan contributes thousands of troops to the Saudi-led coalition. Since the ousting of former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in April this year, Sudanese military leaders had reiterated Khartoum’s commitment to the coalition.[12]

The UAE also has removed its personnel and military equipment from Marib governorate – though its presence there has been minimal since the early stages of the intervention, where Saudi Arabia has been the dominant coalition actor.[13] There are also no signs of any drawdown from bases in Hadramawt and Shabwa governorates, suggesting that claims of a “UAE withdrawal” are mischaracterizing changes to only one aspect of the Emirati presence in Yemen. The drawdown appears to be largely limited to areas of contestation between the Houthis and the Yemeni government, while the UAE-led campaign against Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and presence in strategic areas in the south and southeast of the country remain unchanged. Meanwhile, Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan assured Sultan al-Barakani, Yemen’s parliamentary speaker, that Yemen’s security and stability remained of vital importance, according to the official Emirati news agency, WAM, during a visit by Al-Barakani to the UAE in July.

Houthi Cross-Border Attacks Continue, Exhibition Displays New Drone Capacities

Throughout July, Houthi forces continued to launch missiles and armed drones at targets in southern Saudi Arabia. Jizan and Abha airports remain the most frequently targeted, with a July 2 attack on the latter injuring nine people, the state-run Saudi Press Agency said.[14] The Houthis also claimed to have hit a power plant in Abha on July 9 and to have launched drones targeting King Khalid Air Base near Khamis Mushait on multiple occasions during the second half of the month.[15]

The coalition also said they intercepted an explosive-laden Houthi boat on July 8 as it was heading toward a commercial vessel in the southern Red Sea.[16] The Houthis denied the accusation, calling it a “baseless fabrication.”[17] There is currently intense international attention focused on the waterways around the Arabian Peninsula following a series of incidents involving commercial vessels, and amid escalating tensions between Iran and the US and its Gulf allies (see ‘Iran and Rising Regional Tensions’). The Houthis have previously targeted vessels in the waters off Yemen; last summer, Saudi Arabia temporarily suspended oil shipments through the Bab al-Mandab Strait after a Houthi attack on two of its crude oil tankers.

There has been an increase in Houthi extraterritorial attacks this year, following a lull in the second half of 2018. The targets of these attacks are economic as well as military, with armed drones increasingly eclipsing missiles as the Houthis’ weapon of choice. The Houthis displayed some of their new weapons capabilities at an exhibition in Sana’a on July 7. Mahdi al-Mashat, head of the Supreme Political Council – the governing body in Houthi-controlled areas – unveiled new long-range combat and surveillance drones, as well as ballistic and cruise missiles, Houthi-run Al-Masirah news reported.[18] Among them was the latest incarnation of the Samad drone, which the Houthis claim has a range of 1,700 kilometers and said was used in attacks on airports in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Houthi forces spokesman Yahya Sarea said that the new weapons were made in Yemen and were the product of domestic innovation and manufacturing.[19] While there has been no independent assessment of the new weapons, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen concluded in their 2018 report that certain models of drones in the Houthi arsenal or their components originated from Iran.[20]

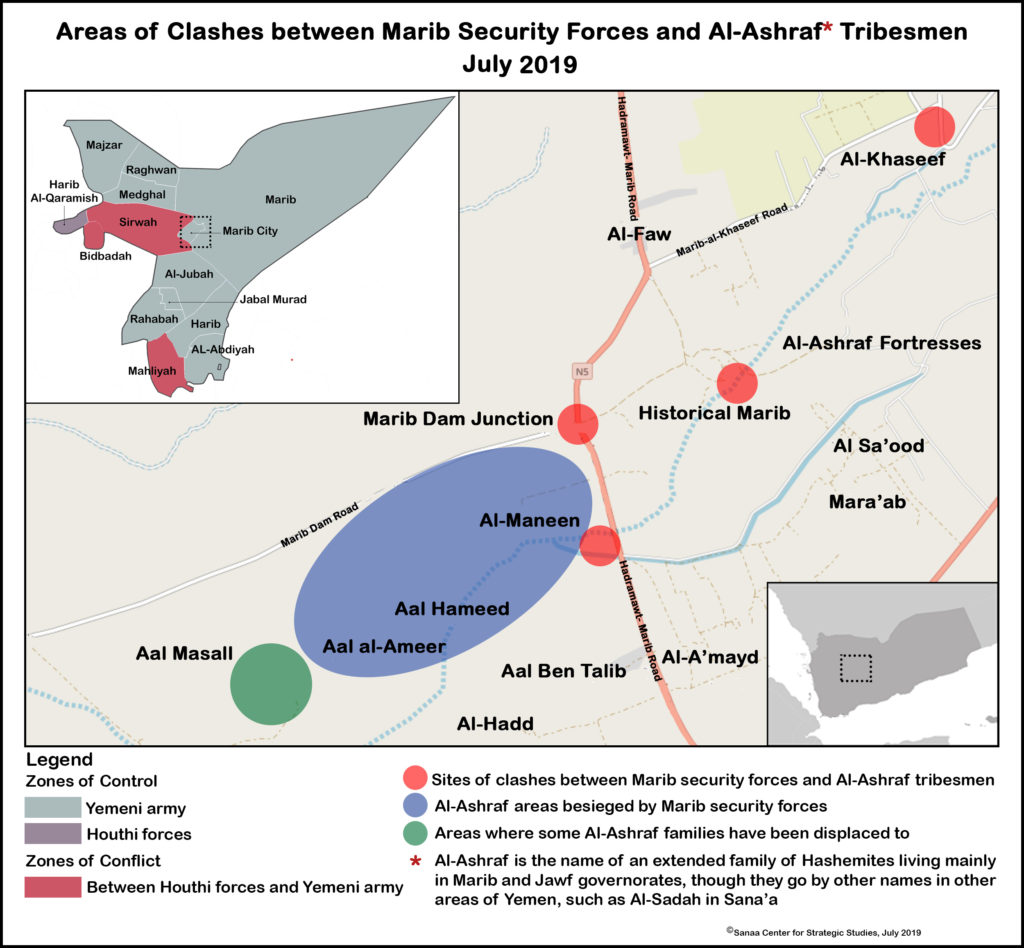

Marib Security Forces Clash with Al-Ashraf Tribesmen

Clashes between security forces and tribesmen in Marib in early July resulted in deaths on both sides, the destruction of homes and the displacement of many residents, local sources told the Sana’a Center. Hostilities began on July 1 when two members of Marib’s security forces were killed during a patrol in the Marib Dam, or Al-Sadd, junction area south of Marib. A security campaign was announced to arrest members of the Al-Ashraf tribesmen who were accused of being involved in the incident.

Local eyewitnesses and a community leader interviewed by the Sana’a Center in Marib said that security forces besieged the Al-Maneen area on July 3, spurring further clashes, which ended with their taking control of the area and arresting 37 tribesmen who the public prosecutor’s office accused of being in alliance with the Houthis. The three days of fighting resulted in the deaths of five civilians, five tribesmen, and nine members of Marib’s security forces, including deputy security director Lt. Col. Mujahid Mabkhout al-Sharif. The local sources added that houses were destroyed during the hostilities and over 100 families displaced from areas where the Al-Ashraf tribesmen dominate.

Military and Security Developments in Brief

- July 3: Fighting between members of the Reyam and Abbas tribes in the contested Rada’ district, Al-Bayda governorate, left 11 dead – including three bystanders – and a further 18 injured.[21]

- July 7: Clashes broke out between the UAE-backed Shabwa Elite Forces and Mihdhar tribesmen in Markah al-Sufla district, northeastern Shabwa.[22] The southeastern governorate is rich in oil and gas resources and has been the site of frequent armed clashes between local actors – even prior to the current conflict. In January, fighting between the Shabwa Elite and Mihdhar tribe in the same area left 15 dead.

- July 11: President Hadi dismissed a senior military figure who criticized the Saudi-led military coalition and said in a media interview that the Saudi-led coalition has not provided the Yemeni armed forces with sufficient resources to defeat the Houthis.[23] Maj. Gen. Mohsen Khosrov, the director of the army’s moral guidance department, has been referred for investigation by the defense ministry for “violations of professional rules and regulations.”

- July 11: Yemen’s Interior Ministry launched a security campaign in Aden’s Dar Saad district after clashes between rival armed groups left dozens dead in recent weeks.[24] As the interim capital’s northern gateway, Dar Saad’s buildings and infrastructure were heavily damaged during the attempted Houthi-Saleh takeover of the city in 2015, and the district has since been contested by the internationally recognized Yemeni government and southern separatists. There were several more assassinations near the end of July.[25]

- July 20: Houthi forces killed Ghawla tribal sheikh Mujahid Qashira in Amran and dragged his body through the streets, with a gruesome video of the event subsequently posted online in a display many commentators said was reminiscent of the Islamic State.

- July 28: A fire broke out at two oil wells in Marib belonging to the government-run SAFER oil company, after tribesmen opened fire on the facilities.[26] There were clashes between members of the Abeida tribe and security forces on July 30 when tribesmen blocked a road near the SAFER oil fields and demanded the return of a vehicle, seized in July, containing weapons, a local source told Al-Masdar.[27]

Economic Developments

Analysis: The Challenges to Implementing Decree 49 to Regulate Fuel Imports

At the end of June this year, the internationally recognized Yemeni government issued Decree 49 regarding the regulation of fuel imports. It is a supplementary framework that broadens and builds upon Decree 75, which the government issued in September 2018. The stated aims of Decree 49 are: to limit illegal trading in fuel imports, which have been a major Houthi revenue generator; to reactivate government revenue collection on fuel imports through taxes and customs fees; to improve the health of the fuel trading market and prevent fuel shortages; and to protect the value of the Yemeni rial, given that fuel import financing is widely regarded as the largest factor contributing to currency instability in Yemen. Decree 49 tightens the procedures and controls for importing fuel through making the Aden Refinery Company (ARC), the country’s sole legal importer of fuel, with the ARC responsible for certifying that the fuel was sourced legally and is of acceptable quality. There is, however, an exception in the text that would allow the private sector actors to import under the supervision of the ARC.

An important question is whether the ARC has enough institutional and human resource capacities, as well as the needed experience, to carry out the tasks Decree 49 asks of it. As of the end of July, the ARC appeared to lack the essential expertise and overall capabilities to facilitate fuel importing procedures, such as carrying out technical examination of the fuel when it arrives and having a platform to sell the fuel to potential distributors.

Another issue is embedded in the implementation mechanism for purchasing fuel from the company in Aden. Decree 49 mandates that in-country distributors purchase fuel from the ARC in local currency, though without stipulating whether this should be in cash or by check. Given the hard currency liquidity crisis, this omission is salient, as transferring cash from Houthi-controlled areas to government-controlled areas has become increasingly difficult as the conflict has progressed. Due to insecurity along the road networks, transferred banknotes are exposed to risks of theft, confiscation, and higher transportation costs. Moreover, the authorities in Sana’a are heavily restricting traders and banks from transferring cash out of Houthi-controlled areas.

Approved private sector fuel importers would have to meet the requirements of Decree 75, including depositing receipts of fuel sold locally in a Yemeni commercial bank, paying government taxes and customs for offloading shipped fuel, and abiding by any other regulatory provisions issued by the Aden-based central bank and Economic Committee. Houthi authorities have resisted, and threatened traders against following, any of these provisions. Thus, fully implementing Decree 49 will likely be difficult given the conflicting policies and regulations issued from Aden and Sana’a. These conflicts also have the potential to limit the quantities of fuel supplied to the market in northern areas and spur critical shortages.

Imposing taxes and customs on imported fuel would also potentially increase the cost of locally sold fuel, directly because of the immediate financial burden, and indirectly because fuel importers and traders have an incentive to keep their profit margins high, as well as the added costs of the new, complicated procedures surrounding fuel imports.

Another issue surrounding the ARC monopolizing most fuel imports is that it would contribute to the depletion of foreign currency reserves at the central bank in Aden. Aden is a secondary money exchange market where it would be difficult to source enough foreign currency to finance the country’s fuel import needs other than from the central bank, whereas in Sana’a – the center of the country’s financial and business activity – fuel importers are generally more able to source foreign currency from the market. The Sana’a Center Economic Unit’s analysis is that centralizing the country’s fuel imports through the ARC misses the opportunity of having a broadly diversified tool in which foreign funds are extracted from a wide variety of financial sources.

Aden Announces Preferential Exchange Rate on Most Import Financing

On July 14, the central bank in Aden announced that it would offer traders a fixed exchange rate of YR506 per US$1 to finance all imports – with the exception of luxury items – that are not covered under the current financing mechanism, in which five basic foodstuff categories are financed at YR440 per US$1. The YR506 rate is more than 10 percent cheaper than buying foreign currency on the open market, relative to the average July exchange rate.

The Sana’a Center Economic Unit analysis is that the new import financing regime could play a major role in helping to restore the value of the Yemeni rial, which was trading at an average of YR580 per US$1 in July.

Corruption Investigation Launched Against Al-Mahra Governor

On July 10, the Yemeni government’s Public Prosecution Office launched a corruption case against the governor of Al-Mahra governorate, Rajih Bakrit. In a letter posted to the central bank in Yemen’s Facebook page, central bank governor Hafez Muayad called on the central bank’s Al-Mahra branch to freeze a local government account while the corruption case proceeds.

Governor Bakrit has been ordering the local tax and customs authorities to deposit what are regarded as central government revenues into an account opened for the local government. He is not alone in this, however. Governorates in areas ostensibly controlled by the Yemeni government – specifically Al-Mahra, Hadramawt, Shabwa, and Marib – have, during the conflict, pursued financial and decision making autonomy from the Yemeni government, which is weak and essentially non-existent at the subnational level in many areas. These kinds of moves by local authorities are illegal, in that they contravene the Local Authority Law of 2000 that governs the activities of local authorities.

Aden Central Bank Issues New YR100 Banknote

In the first half of July, the Aden central bank issued a new YR100 banknote, printed in a different color and with different characteristics than the former YR100 banknote, including a new depiction of the famous Dragon Blood Tree, unique to Socotra. The Houthi authorities in Sana’a have had a standing policy banning in areas they control the use of new banknotes issued in Aden – particularly for banks, which are not allowed to have the new banknotes in their treasuries. The obvious differences between the new and former YR100 bill will make it easy for the Houthi authorities to identify which business and financial institutions have accepted the new banknote. Indeed, on July 11 the Houthi authorities issued a statement reiterating that any quantities of new bills issued from Aden would be “confiscated and destroyed” and the businesses that accepted them would be shutdown. The issuance of the new bills will thus likely add to the chaos of the country’s already fragmented monetary policy. The absence of a unified policy on currency printing and circulation during the war has made financial transactions for individuals, businesses and financial institutions increasingly difficult.

In Focus: Houthi Authorities Sentence 30 Detainees to Death

A Houthi-run court sentenced 30 people to death on July 9 in a mass trial of 36 detainees described as a sham by human rights groups, lawyers and detainees’ relatives.[28]

Speaking to the Sana’a Center, lawyer Abdulmajeed Musleh Sabra, who represented 26 of the defendants, said those on trial had been detained between October 2015 and January 2017, mainly by members of Houthi popular committees. Most were arrested in night raids on defendants’ homes, Sabra said, while some had been pressured to give themselves up after Houthi authorities detained their relatives. Defendant Sadam Dukhan handed himself in after his father and three brothers were arrested by Houthi authorities, Sabra said. The arrest of relatives was also used by Houthi authorities as a tactic to force the detainees to make false confessions, he added.

Houthi authorities did not confirm they were holding the detainees for several months and defendants were transferred between prisons without their families’ knowledge, their lawyer and relatives said. According to their lawyer, detainees were taken to the Criminal Investigation Department and Al-Thawra prison before being moved to the prison of the Political Security Office – Yemen’s intelligence prison where terrorists suspects are usually held and where some Houthis had been imprisoned during Sa’ada wars in the 2000s.

Most detainees were accused of association with the Saudi-led military coalition or of membership in “armed gangs,” Sabra said. He added that the detentions were politically-motivated: the detainees disagreed — politically or religiously — with the Houthis, said Sabra, who was appointed to their case by the Abductees Mothers Association.

Houthi authorities used torture to force false confessions, their lawyer and relatives said. The confessions were videotaped and broadcast on Houthi-affiliated TV stations and social media, a practice which is illegal under Yemeni law, Sabra said. This harmed the defendants’ right to the presumption of innocence and a just trial, and damaged their reputations, he noted.

‘Students and Scholars’

The wife of Mohammed Yahya Akiri, 46, said he was convicted of instigation against the armed Houthi movement and sentenced to death. The family tried to negotiate Akiri’s release with Houthi authorities through neighbors who are Houthi leaders, but failed; some family members joined the Houthi movement to try and free him but this also yielded no result, his wife told the Sana’a Center. She said Akiri was among the prisoners listed to be released under the stalled UN-led prisoner exchange, which was part of the December 2018 Stockholm Agreement.[29] She is allowed to visit her husband fortnightly, but not for more than 10 minutes.

Akiri’s wife urged the international community to work to overturn the convictions, which she said were unjust. “They are students and scholars,” she said; her husband holds a PhD with honors from studying in Sudan. Akiri’s mental health is strong because he is confident of his innocence, his wife said, but she and her seven children are struggling as he was the sole breadwinner.

The sister of Mohammad Hezam al-Yemeni, 40, said she did not know what he was convicted of, as the family had heard multiple different accusations. Al-Yemeni, who was among those sentenced to death, has three children aged between 11 and 16. Al-Yemeni’s sister said she heard he was to be included in the prisoner exchange but had not been able to confirm it.

‘Captured for Extortion’

Another detainee has only been allowed one family visit of a few minutes since he was detained in 2016, his brother said. “We did not know anything about him for a year until tribal mediators intervened and we were told he was arrested by Houthis,” he told the Sana’a Center, on condition of anonymity due to fears for his brother’s safety.

Houthi authorities contact the family with different requests from time to time, asking for money through mediators or to send family members to fight on the frontlines, he said. The trials are a sham, the relative said, and family members are only informed of developments through the media. Initially, the detainee was accused of membership in the Islah party, and then of affiliation with Saudi Arabia, his brother said. The latest accusation is that the detainee is a spy for the Saudi-led military coalition, he said, adding that his brother is not a member of any political party.

Family members were not allowed to send the detainee anything until this year, when they were given permission to send medicine, the brother said, but they do not know if he receives it. The detainee has two children aged 5 and 7 and is suffering mentally from his detention and cruel treatment, his brother added.

Houthi authorities assigned his lawyer after they rejected the lawyer the family appointed. The detainee was also among those listed in the stalled UN-led prisoner exchange, his brother said.

Family members who spoke to the Sana’a Center said the detainees were held in unsanitary conditions, in some cases in dark rooms without sunlight, and have developed a number of diseases in custody. Houthi authorities arbitrarily forbid relatives from sending certain items, such as groceries, fruit, winter clothes and colored underwear.

The Abductees Mothers Association says the detainees are suffering from multiple health problems, including infections, broken bones, kidney disease, heart problems and epilepsy. They have been tortured physically and psychologically, placed in solitary confinement and denied medical treatment, the association said.

In July, the Abductees Mothers Association held demonstrations in Sana’a, Marib, Aden, Taiz and Ibb to protest the death sentences.[30] The organization condemned the death sentences in a statement.[31] The detainees’ families and their lawyers said they will appeal the sentences. The UN office for human rights urged the Appellate court to consider the allegations of torture and violations of fair trial rights of those convicted.[32] It said it was “alarmed” by the sentences. The UN Special Envoy and the US State Department also expressed concern.[33]

The Houthi-run Ministry of Justice in Sana’a published on its facebook page a statement after the trial announcing the death sentences of the 30 detainees, as well as the innocent verdicts of the other six defendants.[34] The statement said they were convicted of belonging to an armed gang that carried out bombings and assassinations, as well as communicating with and supporting “the enemy”.

Humanitarian Developments

WFP, Houthis Reach Agreement to Resume Food Aid to Sana’a

World Food Programme (WFP) Executive Director David Beasley told the UN Security Council on July 18 that his agency had made “substantial progress” in negotiations with the Houthi movement to resume food aid deliveries to Sana’a City and that an agreement had been reached “in principle.”[35] The WFP in June partially suspended assistance to Sana’a over the diversion of food aid in Houthi-controlled areas. The move followed a breakdown in negotiations with Houthi authorities to introduce controls that would ensure aid reached vulnerable Yemenis.[36] The disagreement centers on the use of biometric data registration to identify beneficiaries and monitor distribution, which Houthi authorities regard as a threat to “national security.”[37] On August 4 the WFP and Houthi leadership signed an agreement to reinstate aid deliveries in Sana’a.[38]

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments in Brief

- July 3: Yahya al-Sewari, a Yemeni journalist and photographer specializing in al-Mahra and Socotra governorates, was arrested by security forces in al-Mahra.[39] Al-Sewari had been conducting research on Al-Mahra for the Sana’a Center for the previous six months.

- July 9: A Houthi-run court sentenced 23-year-old Asma’a al-Omeissy to 15-years in prison.[40] A mother of two, Al-Omeissy was convicted of aiding an enemy state. Al-Omeissy had been sentenced to death in a Houthi-run court in January 2018, along with two other defendants; her father Matir Al-Omeissy was sentenced to 15 years at the same trial.[41] At the time, Amnesty International said the trial followed “a catalogue of grave violations and crimes under international law, some of which may also amount to war crimes.”

- July 18: In a briefing to the UN Security Council, UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock said more than 300,000 people had been displaced in Yemen in 2019.[42]

- July 29: Fourteen people were killed, including four children, and 26 were injured in an attack on Al-Thabit market in Qatabir district of Sa’ada governorate, according to local health authorities.[43] Fourteen children were among the wounded who were taken to hospitals in Sana’a and Sa’ada. Houthi authorities said Saudi forces had bombed the market, while the Yemeni government and Saudi-led military coalition blamed Houthi forces for the attack.[44]

- July 30: Some 1,689 children were killed in the Yemen War in 2018, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said in his report on children and armed conflict.[45] Of these, 729 were killed by the Saudi-led military coalition, and 398 by the armed Houthi movement, the report found. Save the Children criticized Guterres for not including the Saudi-led military coalition on its “list of shame” in the annual report.[46] It accused Guterres of placing politics above children and said the lack of accountability showed “states with powerful friends can get away with destroying children’s lives with impunity.”

Shopkeepers mind their stalls in Old Sana’a on July 21, 2019 // Photo Credit: Doaa Sadam

Shopkeepers mind their stalls in Old Sana’a on July 21, 2019 // Photo Credit: Doaa Sadam

International Developments

Iran and Rising Regional Tensions

US Planning Multinational Coalition to Patrol Waters Off Iran and Yemen

US Central Command (CENTCOM) said in July it was forging ahead with plans to create a coalition to safeguard the passage of commercial vessels through waterways in the Gulf. “Operation Sentinel” is to include surveillance and naval escorts in the Strait of Hormuz, the Bab al-Mandab Strait, the Arabian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, CENTCOM said July 19 in a statement.[47] The announcement followed a series of alleged sabotage attacks on vessels in the region’s waterways, which the US has blamed on Iran.

Joseph Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said July 9 that plans were in motion for the coalition and that the Strait of Hormuz and the Bab al-Mandab Strait would be the main focus of the campaign.[48] The Pentagon’s top general said the US role would be restricted to “command and control,” with other countries in the coalition providing the patrol vessels and escorting their own nations’ commercial ships. In later comments, a Pentagon official said the coalition was intended as a deterrent focused on surveillance and would not constitute a military coalition against Iran.[49]

The reaction to the plan has been lukewarm, according to diplomatic and official sources who spoke to Reuters.[50] European and Asian importers of oil from the Gulf have questioned the viability of providing escorts for every one of their commercial vessels and are wary of taking part in what could be seen as an anti-Iran coalition.

Germany’s Vice Chancellor and Finance Minister Olaf Scholz put it plainly in speaking to German media: “I think this is not a good idea.” This réticence will likely be problematic for US designs given that senior American officials have implied the US is seeking a hands-off approach and expects those relying on Gulf oil – particularly Asian countries – to shoulder the costs and manpower requirements of the operation.[51]

The United Kingdom has shown resistance to the US proposal, despite Iran’s seizure of a British tanker in the Strait of Hormuz on July 19 (see ‘Iran Seizes British-flagged Tanker’).[52] Whitehall has instead advocated a European maritime alliance which would either coordinate with the United States or form part of a broader coalition of countries.[53] On July 30, the Guardian quoted Whitehall sources as saying the UK has invited the United States and France to a meeting in Bahrain – which hosts British and American naval bases – to discuss safeguarding of Gulf waters.[54] The three countries already carry out joint anti-mine exercises in Bahraini waters.

Rising tension in the Gulf prompted the United States to send troops to Saudi Arabia in July after a 16-year absence from the kingdom.[55] The deployment comprises 500 troops, a US official said, and is part of a larger authorization of 1,000 additional troops to the Middle East announced in June.[56][57] The troops were sent to Prince Sultan Air Base near Riyadh – a major hub for US military aircraft from the Gulf War up until the withdrawal of its troops from Saudi Arabia in 2003 following the Battle of Baghdad during the invasion of Iraq.

Separately, President Donald Trump said a US warship shot down an Iranian drone that came within “very near distance” of the vessel over the Strait of Hormuz on July 18.[58] Iran said that it had received no information about the loss of a drone and the country’s deputy leader suggested that the US had shot down its own aircraft by mistake.

Iran Seizes British-flagged Tanker; UK Proposes European Protection Force

Iran seized a British-flagged tanker July 19 in the Strait of Hormuz and forced it to sail to the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas, prompting the UK to propose a European protection force off the Iranian coast. Iran’s defense minister, Brig. Gen. Amir Hatami, suggested the Stena Impero was seized in retaliation for the UK seizing a tanker off Gibralter that was suspected of violating EU sanctions by carrying Iranian oil to Syria. Other government officials denied any retaliatory motive, with Iran’s state-run news agency reporting the ship was seized because it had hit a fishing boat, requiring investigation.[59]

Britain announced plans July 22 for the UK to work with European countries to create a protection force in the Gulf, though it was not clear how many and to what extent European governments would be willing to participate. Jeremy Hunt made the announcement a few days before being replaced as Britain’s foreign secretary, saying the force would not include the United States because Britain does not ascribe to Washington’s policy of asserting maximum pressure on Tehran.[60] How the new UK leadership might alter that plan was not immediately clear, but new British Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab told BBC Radio 4 on July 29 that the government still wants to see a European-led approach.[61] Britain announced July 25 that the Royal Navy had begun escorting British-flagged ships through the Strait of Hormuz.[62]

Meanwhile, on July 18 the International Maritime Organization (IMO) executive council, meeting in London, urged ship owners and operators to review and improve their safety plans as needed given recent attacks on commercial ships in the Strait of Hormuz and off the coast of Yemen. Secretary-General Kitack Lim urged IMO states to work harder to resolve the situation.[63] The United States, United Kingdom and United Arab Emirates sit on the 40-member IMO executive body; Iran, Saudi Arabia and Yemen are also IMO member states.

EU Tries to Salvage Iran Nuclear Deal, Provide Sanctions Relief

European Union foreign ministers sought in July to salvage the Iran nuclear deal, agreeing their emerging back-channel trading system needs improving if it is to provide real sanctions relief and acknowledging it may be used for Iranian oil sales.

Federica Mogherini, the EU foreign policy chief, acknowledged July 15 that European shareholders in the new system, known as INSTEX (Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges) have discussed allowing oil sales.[64] This prompted the United States to warn against trying to evade its sanctions.[65] Iranian officials, frustrated the Europeans have yet to provide any sanctions relief, called INSTEX a step forward, but said it must include oil and financial transactions.

INSTEX creates a channel to trade with Iran that can circumvent US sanctions by avoiding cross-border money transfers via the SWIFT international payment network. It functions much like a barter system in which no money is transferred in or out of Iran. Instead, a European country wanting to import from Iran pays a second European company wanting to export a product to Iran. It is operational, processing its first transactions, but is slow and currently restricted to humanitarian trade, such as food and medicine.

European countries are keen to ease tension in the Gulf, and have been trying to do so by pressing Iran to stick with the 2015 nuclear deal despite Washington’s withdrawal from it and decision to reimpose sanctions on Tehran. On July 15, European foreign ministers discussed the risk that a miscalculation could lead to war between Iran and the United States.[66] Leaders of France, Germany and Britain – signatories to the nuclear deal – issued a joint statement July 14, urging dialogue and saying the risks were such that all parties must “pause and consider the possible consequences of their actions.”[67]

Iranian FM: Trump Doesn’t Want War, His Aides Do

Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif said in an interview July 16 with NBC News that Tehran is willing to negotiate nuclear issues after US President Donald Trump lifts the sanctions he has imposed since 2017. Zarif, who was interviewed while attending UN meetings in New York, downplayed talk of war, saying he does not believe Trump wants war, “but I believe that people are around him who wouldn’t mind.”[68] Trump, who withdrew the United States from the nuclear deal last year, repeatedly has said he wants to renegotiate it, but also has been enacting additional sanctions.

On July 31, The Trump administration imposed sanctions on Zarif after threatening to do so the previous month. The unusual move of sanctioning another country’s chief diplomat further hurts the chances of diplomatic talks between the United States and Iran to lower the current tensions. Washington also said it would review Zarif’s requests for travel visas to New York to visit the United Nations on a case by case basis.[69] The United Nations expressed concern to the United States over increased travel restrictions on Zarif during his visit to New York in July, a UN spokesperson said July 15.[70}

At the United Nations

Warring Parties Meet Regarding Hudaydah Ceasefire

Representatives from the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the armed Houthi Movement met July 14-15 to discuss steps to jumpstart the implementation of the Stockholm Agreement. The fifth meeting of the UN’s Redeployment Coordination Committee (RCC) – hosted by its chair General Michael Lollesgaard aboard a ship on the Red Sea – was the first since February 2019 and followed a recent increase in ceasefire violations in Hudaydah City and the wider governorate. The rival delegations boarded the UN vessel in separate locations off the coast of Mokha and Hudaydah.

In a statement after the gathering, Lollesgaard said the parties had agreed on mechanisms to monitor the ceasefire in Hudaydah.[71] The RCC also finalized “concepts of operations” for Phases I and II of the mutual redeployment of forces from Hudaydah City, Lollesgaard said.[72] The UN has previously said that the two-phased withdrawal plan envisioned fighters pulling back 18 to 30 kilometers from Hudaydah to allow for the total demilitarization of the city and the return of civilian life.[73]

With these agreements, Lollesgaard said the committee had finalized its technical work and awaited decisions from political leaderships to proceed with implementation. Major stumbling blocks remain unresolved, including the issue of what to do with revenues from the three ports around Hudaydah,[74] the composition of local security forces to replace withdrawing troops, and governance post-withdrawal.

In his briefing to the UN Security Council on July 18, UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths congratulated Lollesgaard for the meeting’s agreements, which he described “an important breakthrough.” He also thanked Lollesgaard for “his collegiality, perseverance and wisdom.” Lollesgaard’s contract is set to expire in early August, and his last day as RCC chair was scheduled for July 31, according to Sana’a Center sources. As of this writing, no official announcement has been made regarding his departure or potential replacement.

Griffiths pledged to increase his efforts to solve the outstanding hurdles to the Hudaydah withdrawal – most notably on local security forces and port revenues. He said that solving the issue of Hudaydah may allow the UN to renew its focus on Yemen’s political process before the end of the summer.

On July 15, the Security Council voted unanimously to extend the mandate of the UN Mission to support the Hudaydah Agreement (UNHMA), which leads the RCC, to January 15, 2020, and called for the deployment of a full contingent of observers. Though the mission is mandated to have 75 staff, only 20 are present on the ground, due largely to the armed Houthi movement refusing to grant visas for the additional observers.[75]

UN Envoy Engages in Shuttle Diplomacy on Yemen Peace Process

UN Special Envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths met with Yemeni parties to the conflict and international stakeholders in a whirlwind July tour to jumpstart the flagging Yemen peace process. These included visits to Russia, the UAE, the US, as well as meeting Houthi officials in Muscat and Sana’a. Griffiths also met with President Hadi in Saudi Arabia on July 15, their first meeting since Hadi threatened to stop cooperating with the envoy in late May. While in Saudi Arabia, Griffiths also met with Yemeni Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, and with Saudi Deputy Minister of Defense Khalid bin Salman in Jeddah.

In the United States

Trump Vetoes Resolutions to Block Expedited Weapons Sales to Saudi Arabia, UAE

President Trump vetoed three resolutions that sought to block emergency weapons sales to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, including the type of missiles used by the coalition in Yemen. In his veto message published July 24, Trump said blocking the sales would harm US-Saudi relations and security cooperation.[76] He justified the weapons as defensive, citing Houthi cross-border attacks into Saudi Arabia and the threat to US citizens residing in the kingdom. In three votes on July 29, the Senate failed to reach the two-thirds majority required to overturn the vetoes.

In May, the Trump administration used an emergency powers provision to push through $8 billion worth of weapons transfers to Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Jordan, citing the threat posed by Iran and its regional proxy forces.[77] This includes $2 billion worth of proposed sales of precision-guided munitions (PGMs) to Saudi Arabia held up for over a year by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee due to concerns over their threat to civilian lives in Yemen.

The US House of Representatives had voted to block emergency the sales on July 17.[78] Two of the resolutions passed the Democrat-led House 238-190, and the third 237-190, with only four Republicans and one independent crossing the aisle. These were three of 22 bills relating to the arms transfers that already passed the Senate in June.

Vetoing the resolutions, Trump said PGMs reduced the risk of civilian casualties — a common refrain among those supporting continued offensive weapons sales to coalition member states. Others have argued the civilian casualty figures from the coalition airstrike campaign — which includes use of such precision weapons — discredited this argument.[79]

In Europe

New UK Foreign Secretary: A Brexiter with Limited Mideast Experience

Britain’s new prime minister, Boris Johnson, has replaced UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt with Dominic Raab, a Brexit hardliner with limited Middle East experience. To date, Britain has played a key role in the Yemen war, both as the second-largest arms supplier to the Saudi-led coalition and as penholder of the Yemen file at the UN Security Council – meaning the British mission drafts all council products related to Yemen. Martin Griffiths, the British diplomat turned UN special envoy, runs the world body’s peace efforts in Yemen, while Britain is also part of the “Quad”, a multilateral group including the US, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which is working on the Yemen crisis in parallel to the UN process.

As Griffiths’ efforts to implement the Stockholm Agreement foundered this year, Hunt traveled to Riyadh and Dubai trying to get the deal back on track (See ‘“Last Chance Saloon” for Peace Process: UK Foreign Secretary – The Yemen Review, March 2019‘). Hunt became the first Western foreign minister since 2015 – and the first UK Foreign Secretary since 1996 – to visit Yemen, meeting in Aden with officials from the internationally-backed Yemeni government. He also met with the Houthi authority’s chief negotiator, Mohammed Abdel Salam, in Oman.[80]

Dominic Raab, a former junior minister in charge of Brexit policy and former Foreign Office lawyer, was appointed UK foreign secretary on July 24. His record has focused primarily on European and UK issues, though he has in the past shown wariness of British involvement in Middle East disputes.[81]

Other International Developments

China Eyes Bigger Role in Yemen

Yemeni Prime Minister Maeen Abdul Malik and China’s ambassador to Yemen, Kang Yong, spoke July 21 in Riyadh about a role for China in rebuilding post-war Yemen, according to the official Saudi Press Agency. It gave few details, but also reported Abdul Malik was confident China would use its influence on the UN Security Council to pressure Iran “to stop its destructive role in Yemen.”[82] A day later, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan, crown prince of Abu Dhabi, received a red-carpet welcome in Beijing, where he and Chinese President Xi Jinping discussed further cooperation, including in trade and energy. Sheikh Mohammed also welcomed a bigger role for China in maintaining Middle East peace and stability, China’s official Xinhua news agency reported.[83]

Hamas Member Killed in Marib

A member of the Palestinian movement Hamas was killed at a checkpoint in Marib governorate on July 12, according to a Palestinian security source that spoke to Reuters. The security source said Salim Ahmed Maarouf, 36, had been living in Yemen for more than 15 years but did not comment further regarding his activities.

Other International Developments in Brief

- July 9: Canada’s leftist New Democratic Party (NDP) criticized the government for failing to deliver a timetable for its review of arms exports to Saudi Arabia more than eight months after committing to it, complaining Canadian weapons continue to fuel the Yemen war.[84] The Canadian government has come under heavy criticism for a multi-year, US$11.5 billion arms deal with Riyadh, and a review of export permits is reportedly underway. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has noted cancelation penalties could approach US$1 billion.[85] The NDP also urged Canada to skip next year’s G20 summit in Riyadh.

- July 16: Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) denied any connections to the Bahraini government after an Al-Jazeera report alleged one of its Bahraini supporters had accepted a royal request to target Manama’s political opponents.[86] The AQAP statement also denied ties to other regional governments, specifically the UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as any past links to the late Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh. Bahrain’s government-run media denounced the report repeatedly as lies and Qatari meddling.[87]

- July 20: The Saudi Press Agency reported that Saudi authorities transferred an injured Iranian sailor from the Iranian ship Safiz, anchored northwest of Hudaydah, Yemen, to Oman after he was treated in Jizan, Saudi Arabia, according to the official Saudi Press Agency.88 SPA noted the kingdom treated and then transferred the sailor at Iran’s request “despite the threat being posed by this suspicious ship.”

This report was prepared by (in alphabetical order): Ali Abdullah, Waleed Alhariri, Ryan Bailey, Hamza Al-Hamadi, Maged Al-Madhaji, Farea Al-Muslimi, Spencer Osberg, Hannah Patchett, Ghaidaa Al-Rashidy, Susan Sevareid, Sala Al-Sakkaf and Holly Topham.

The Yemen Review – formerly known as Yemen at the UN – is a monthly publication produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. Launched in June 2016, it aims to identify and assess current diplomatic, economic, political, military, security, humanitarian and human rights developments related to Yemen.

In producing The Yemen Review, Sana’a Center staff throughout Yemen and around the world gather information, conduct research, and hold private meetings with local, regional, and international stakeholders in order to analyze domestic and international developments regarding Yemen.

This monthly series is designed to provide readers with contextualized insight into the country’s most important ongoing issues.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Endnotes

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606.

- “Daesh claims the attack on the Sheikh Osman police station in Aden and announces the name of the attacker” Al-Masdar Online, August 3, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/170257.

- “Urgent: Ministry of Interior issues an important statement on the targeting of Al-Jalaa camp and the bombing of Sheikh Othman police station and publishes the results of the two operations,” Al-Wattan, Aug. 1, 2019, http://alwattan.net/news/80783.

- Maeen Abdul Malik, remarks on his official Twitter account, August 1, 2019, https://twitter.com/DrMaeenSaeed/status/1156890013155676160

- “Air Force Command and missile force targeted a camp for invaders and mercenaries of Aden and killed and wounded dozens,” Al-Masirah, August 1, 2019. https://almasirah.net/details.php?es_id=43128&cat_id=3.

- Anwar Gargash, twitter account of the minister of state for foreign affairs, August 2, 2019, https://twitter.com/AnwarGargash.

- “The decision of the President of the Republic to appoint Maj. Gen. Aziz bin Aziz as commander of the Joint Operations of the Armed Forces and Brig. Muhsin al-Da’ari as Assistant Commander,” Saba Net, July 11, 2019, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/51666.

- Aziz El Yaakoubi and Mohamed Ghobari,“Saudi Arabia moves to secure Yemen Red Sea ports after UAE drawdown,” Reuters, July 11, 2019, https://ca.reuters.com/article/topNews/idCAKCN1U61YJ-OCATP.

- Shukri Hussein, “Sudanese forces partially withdraw from Yemen,” Anadolu Agency, July 24, 2019,https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/sudanese-forces-partially-withdraw-from-yemen-/1540335.

- “Sudanese troops withdraw from three positions on West Coast front,” Al-Masdar News, July 2, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/article/sudanese-troops-withdraw-from-3-positions-on-west-coast-front.

- “Evidence confirms the presence of Sudanese forces in Yemen,” Yemen News Now, July 31, 2019, https://www.yemenakhbar.com/2057841.

- Ali Mahmood, “Sudanese forces not withdrawing from Yemen’s Hodeidah, spokesman says”, The National, July 25, 2019, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/sudanese-forces-not-withdrawing-from-yemen-s-hodeidah-spokesman-says-1.890502.

- “Military source: UAE withdraws its last soldier from Marib,” Al-Mawqea Post, July 1, 2019, https://almawqeapost.net/news/41447.

- “A number of countries, organizations condemn Huthi attack on Abha Int’l airport,” Saudi Press Agency, July 2, 2019. https://www.spa.gov.sa/1940820.

- Twitter Post, Al-Masirah TV, @MasirahTV, July 8, 2019, https://twitter.com/MasirahTV/status/1148319395191689216.

- “Maliki: Houthi Iranian boats: We will work to ensure freedom of navigation.” Sky News Arabia, July 10, 2019, https://bit.ly/2GB8kCv.

- Twitter Post, Al-Masirah TV, @MasirahTV, July 8, 2019, https://twitter.com/MasirahTV/status/1148254046047952896.

- “Detection of new weapons in the Martyr Al-Samad exhibition for the Yemeni military industries,” Al-Masirah, July 7, 2019, https://almasirah.net/details.php?es_id=42137&cat_id=3..

- “A Spokesman For The Armed Forces Reviews In A Press Briefing New Details About The Yemeni Military Industries,” Ansar Allah official website, July 9, 2019,https://www.ansarollah.com/archives/262426.

- pp.32, “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen,” United Nations, 26 January 26 2018, https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2018/594. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- “Al-Bayda: 11 people killed and 18 wounded in tribal clashes in Rada,’” Al-Masdar News, July 3, 2019,. https://almasdaronline.com/articles/169227. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- “Renewed clashes between Elite forces and tribal gunmen in Shabwah,” Al-Masdar News, July 7, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/169361.

- “Presidential directives to suspend the director of the Department of Moral Guidance and refer him to the investigation,” Saba Net, July 11, 2019, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/51632.

- “A large security campaign under the supervision of al-Misri and Brigadier Rashid, commander of the UAE forces to impose security,” Aden al-Ghad, July 11, 2019, http://old.adengd.net/news/396492/#.XT9G-pMzYWp.

- “The third assassination in 72 hours. Unidentified gunman kills two young men in Dar Saad, north of Aden,” Al-Masdar News, July 27, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/170009.

- “Fire breaks out in two oil wells in Marib’s “Safar” fields due to fire shoots,” Al Masdar, July 28, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/article/fire-breaks-out-in-two-oil-wells-in-maribs-safar-fields-due-to-fire-shoots.

- “Military campaign clash with tribal gunmen near Safar oil fields in Marib,” Al-Masdar, July 30, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/article/military-campaign-clashing-with-tribal-gunmen-near-safar-oil-fields-in-marib.

- “Yemen: Huthi-run court sentences 30 political opposition figures to death following sham trial,” Amnesty International, July 9, 2019, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/07/yemen-huthi-run-court-sentences-30-political-opposition-figures-to-death-following-sham-trial/.

- “Full text of the Stockholm Agreement,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, December 13, 2018, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/full-text-stockholm-agreement.

- Facebook posts, Abductees Mothers Association, https://mobile.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=1113322522188767&id=505200403000985&_rdc=1&_rdr;

- Twitter post, Abductees Mothers Association, July 20, 2019, https://twitter.com/abducteesmother/status/1152538573402443776?s=20.

- “Press briefing note on Yemen,” UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, July 12, 2019, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24816&LangID=E.

- Twitter post, Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, July 14, 2019, https://twitter.com/OSE_Yemen/status/1150392978395009025?s=20; Twitter post, US State Department media liaison office, July 14, 2019, https://twitter.com/USAbilAraby/status/1150341097756987392?s=20.

- Facebook Post, Yemeni Ministry of Justice, July 9, 2019, https://www.facebook.com/652894871548615/posts/1242644132573683/?sfnsn=mo&_rdc=2&_rdr.

- “World Food Programme (WFP) Executive Director briefs UN Security council on situation Yemen,” World Food Programme Insight, July 18, 2019, https://insight.wfp.org/world-food-programme-wfp-executive-director-briefs-un-security-council-on-situation-in-yemen-c4065b2223f6.

- “World Food Programme begins partial suspension of aid in Yemen,” World Food Programme, June 20, 2019, https://www1.wfp.org/news/world-food-programme-begins-partial-suspension-aid-yemen.

- “UN gives ultimatum to Yemen rebels over reports of aid theft,” The New Humanitarian, June 17, 2019, http://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2019/06/17/un-yemen-rebels-aid-theft-biometrics.

- “الحوثيون يوقعون اتفاقاً مع برنامج الغذاء لاستئناف توزيع المساعدات“ (“Houthis sign agreement with food program to resume distribution of aid”), Al-Mushahid, August 4, 2019, https:// https://almushahid.net/47423/

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606.

- “Yemen: Huthi-run court sentences 30 political opposition figures to death following sham trial,” Amnesty International, July 9, 2019, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/07/yemen-huthi-run-court-sentences-30-political-opposition-figures-to-death-following-sham-trial/.

- “Huthi-run court sentences three to death after enforced disappearance and alleged torture,” Amnesty International, February 15, 2018, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2018/02/yemen-huthi-court-sentences-three-to-death-after-enforced-disappearance-and-alleged-torture/.

- “Hodeidah Ceasefire Holding But Faster Progress Key to Stopping Yemen from Sliding into Regional War, Deepening Humanitarian Crisis, Speakers Tell Security Council,” United Nations, July 18, 2019, .https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sc13887.doc.htm.

- “Statement by the Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen, 30 July 2019: Children are among scores of civilians, killed and injured by an attack on a market in Sa’ada [EN/AR]”, ReliefWeb, July 30, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/statement-humanitarian-coordinator-yemen-30-july-2019-children-are-among-scores.

- Sharif Paget, Ghazi Balkiz and Tara John, “Four children killed in attack on Yemen market,” CNN, July 30, 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/30/middleeast/yemen-market-explosion-saada-intl/index.html.

- “Record Number of Children Killed and Maimed in 2018, Urgent to Put in Place Measures to Prevent Violations,” United Nations, July 30, 2019, https://childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/record-number-of-children-killed-and-maimed-in-2018-urgent-to-put-in-place-measures-to-prevent-violations/.

- “Save the Children on UN report on children in armed conflict: ‘States with powerful friends can get away with destroying children’s lives,’” ReliefWeb, July 30, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/save-children-un-report-children-armed-conflict-states-powerful-friends-can-get-away.

- “U.S. Central Command Statement on Operation Sentinel,” U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), July 19, 2019, https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/STATEMENTS/Statements-View/Article/1911282/us-central-command-statement-on-operation-sentinel/.

- Phil Stewart, “U.S. wants military coalition to safeguard waters off Iran, Yemen,” Reuters, July 10, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-iran-usa-coalition/us-wants-military-coalition-to-safeguard-waters-off-iran-yemen-idUSKCN1U42KP.

- Phil Stewart, “Exclusive: U.S. Gulf maritime proposal not military coalition against Iran – Pentagon official,” Reuters, July 18, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-iran-usa-maritime-exclusive/exclusive-u-s-gulf-maritime-proposal-not-military-coalition-against-iran-pentagon-official-idUSKCN1UD2O5.

- Sylvia Westall and John Irish, “Allies play hard to get on U.S. proposal to protect oil shipping lanes,” Reuters, July 19, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-iran-tanker-allies/allies-play-hard-to-get-on-u-s-proposal-to-protect-oil-shipping-lanes-idUSKCN1UE0KI.

- David B. Larter, “Don’t expect the US to secure Arabian Gulf shipping alone, a top general says,” Bloomberg, June 18, 2019, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2019/06/18/dont-expect-the-us-to-secure-arabian-gulf-shipping-alone-top-general-says/.

- “Iran seizes British tanker in Strait of Hormuz,” BBC News, July 20, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-49053383.

- “”Situation in the Gulf,” House of Commons Hansard, Vol. 663, 22 July 2019, https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2019-07-22/debates/1436057A-CE0D-4FBB-AF23-CD93E4AFFA0A/SituationInTheGulf.

- Dan Sabbagh, “UK calls meeting with US and France to discuss Hormuz plan,” The Guardian, July 30, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/30/uk-us-europe-shipping-strait-of-hormuz.

- “U.S. Central Command Statement on movement of U.S. personnel to Saudi Arabia,” U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), July 19, 2019, https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/STATEMENTS/Statements-View/Article/1911277/us-central-command-statement-on-movement-of-us-personnel-to-saudi-arabia/utm_source/hootsuite/.

- Anthony Capaccio, “U.S. Says 500 Troops Sent to Saudi Arabia on Mideast Deployment,” Bloomberg, July 18, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-07-18/u-s-preparing-to-send-500-troops-to-saudi-arabia-cnn.

- “Statement From Acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan on Additional Forces to U.S. Central Command,” Department of Defense, July 17, 2019, https://dod.defense.gov/News/News-Releases/News-Release-View/Article/1879076/statement-from-acting-secretary-of-defense-patrick-shanahan-on-additional-force/.

- “US destroyed Iranian drone in Strait of Hormuz, says Trump,” BBC News, July 19, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-49040415.

- “UK-flagged oil tanker seizure; Iran’s will to respond to threats: Defense Minister,” IRNA, July 24, 2019, https://en.irna.ir/news/83406347/UK-flagged-oil-tanker-seizure-Iran-s-will-to-respond-to-threats

- “Situation in the Gulf,” Hansard, transcript of UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt’s remarks in the House of Commons, July 22, 2019, https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2019-07-22/debates/1436057A-CE0D-4FBB-AF23-CD93E4AFFA0A/SituationInTheGulf.

- Dominic Raab, interview with BBC Radio 4, 2:23:33, July 29, 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m00075hl.

- “Iran tanker seizure: Royal Navy frigate to escort UK ships,” BBC News, July 25, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-49110331

- “International Maritime Organization Council condemns tanker attacks in Strait of Hormuz and Sea of Oman,” IMO press briefing, July 18, 2019, http://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/15-IMO-Council-condemns-tanker-attacks.aspx.

- Lisa Bryant, “EU announces strides in Iran trade mechanism amid nuclear deal scramble,” VOA, July 15, 2019, https://www.voanews.com/europe/eu-announces-strides-iran-trade-mechanism-amid-nuclear-deal-scramble.

- Rob Crilly, “US warns Europe not to develop barter system to evade Iran sanctions,” Washington Examiner, July 26, 2019, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/us-warns-europe-not-to-develop-barter-system-to-evade-iran-sanctions.

- “Foreign Affairs Council, 15/07/2019,” Council of the European Union, July 15, 2019, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/fac/2019/07/15/.

- “Joint statement by the heads of state and government of France, Germany and the United Kingdom,” Elysee Palace, July 14, 2019, https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2019/07/14/joint-statement-by-the-heads-of-state-and-government-of-france-germany-and-the-united-kingdom.

- Dan De Luce, “Door is ‘wide open’ to negotiation if Trump lifts his sanctions on Iran, Zarif says,” NBC News, July 16, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/mideast/door-wide-open-negotiation-if-trump-lifts-his-sanctions-iran-n1030021.

- Jeff Mason, “U.S. puts sanctions on Iranian foreign minister Zarif, who says they won’t affect him,” Retuers, July 31, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-iran-zarif/us-puts-sanctions-on-iranian-foreign-minister-zarif-who-says-they-wont-affect-him-idUSKCN1UQ2O1.

- “Michelle Nichols, “U.N. concerned by U.S. curbs on Iranian foreign minister while in New York,” Reuters, July 15, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-iran-usa-zarif/un-concerned-by-us-curbs-on-iranian-foreign-minister-while-in-new-york-idUSKCN1UA29P.

- “Redeployment Coordination Committee Chairman’s Summary of the Joint Meeting of the Redeployment Coordination Committee,” United Nations Secretary-General, July 15, 2019, https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/note-correspondents/2019-07-15/note-correspondents-redeployment-coordination-committee-chair%E2%80%99s-summary-of-the-joint-meeting-of-the-redeployment-coordination-committee-scroll-down-for-arabic.

- “Redeployment Coordination Committee Chairman’s Summary of the Joint Meeting of the Redeployment Coordination Committee,” United Nations Secretary-General.

- Edith Lederer, “UN Envoy: Yemen parties agree on initial Hodeidah withdrawals,” The Associated Press, April 15, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/8f254a6838f54166bf7a5ab50f7904a8.

- Spencer Osberg and Hannah Patchett, “An Unending Fast: What the Failure of the Amman Meetings Means for Yemen,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 20, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7433.

- UN envoy Griffiths arrives in Sanaa after redeployment meetings between Yemen sides,” Arab News, July 15, 2019, http://www.arabnews.com/node/1526061/saudi-arabia.

- “S.J. Res. 38 Veto Message,” Presidential Memorandum, July 24, 2019. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/s-j-res-38-veto-message/.

- “Amid Escalation with Iran, Trump Administration Expedites Arms Sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE – The Yemen Review, May 2019,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, June 6, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7504#In-the-United-States.

- Richard Lardner, “House votes to block sale of weapons to Saudi Arabia,” The Associated Press, July 18, 2019. https://www.apnews.com/4f7a8c7cd10a45ca9f1b54bd068d1dc7.

- William Hartung, “Trump’s Saudi Arms Vetoes, Deconstructed,” LobeLog, July 26, 2019, https://lobelog.com/trumps-saudi-arms-vetoes-deconstructed/.

- “Last Chance Saloon” for Peace Process: UK Foreign Secretary – The Yemen Review, March 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7269#Last-Chance-Saloon-for-Peace-Process-UK-Foreign-Secretary.

- “UK’s new chief diplomat warned of limits of influence,” The National, July 25, 2019, https://www.thenational.ae/world/europe/uk-s-new-chief-diplomat-warned-of-limits-of-influence-1.890820.

- “Yemen, China discuss bigger role in the region, Saudi Press Agency, July 21, 2019, https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewstory.php?lang=en&newsid=194922.

- “China, UAE pledge to boost comprehensive strategic partnership,” Xinhua, July 23, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-07/23/c_138248606.htm.

- “NDP Statement on the Upcoming G20 Meeting in Saudi Arabia,” NDP press release, July 9, 2019, https://www.ndp.ca/news/ndp-statement-upcoming-g20-meeting-saudi-arabia.

- Jesse Ferreras, “Saudi Arabia expects Canada to proceed with $15B arms deal, but there’s ‘no final decision’,” Global News, March 5, 2019, https://globalnews.ca/news/5021709/saudi-arabia-canada-arms-deal/.

- Written statement released by Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, dated July 16, 2019; image posted by Long War Journal, https://www.longwarjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/D_oED3EVUAAcMWK.jpg; Charles Stratford, “Former al-Qaeda member claims he was hired by Bahrain as assassin,” Al-Jazeera (English), July 19, 2019, Arabic report aired July 14, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/07/al-qaeda-claims-recruitment-bahrain-govt-assassin-190719121811157.html.

- “More Bahraini families reiterate loyalty to royal leadership,” BNA, July 25, 2019, https://www.bna.bh/en/MoreBahrainifamiliesreiterateloyaltytoroyalleadership.aspx?cms=q8FmFJgiscL2fwIzON1%2bDi78QaQsdDkV2tip8YXvIUE%3d

- “Foreign Affairs Ministry’s Official Source: Iranian Citizen Transferred to Sultanate of Oman after Necessary Medical Care Provided to him in Saudi Specialized Hospital,” SPA, July 20, 2019, https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=1948743#1948743.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

S

S