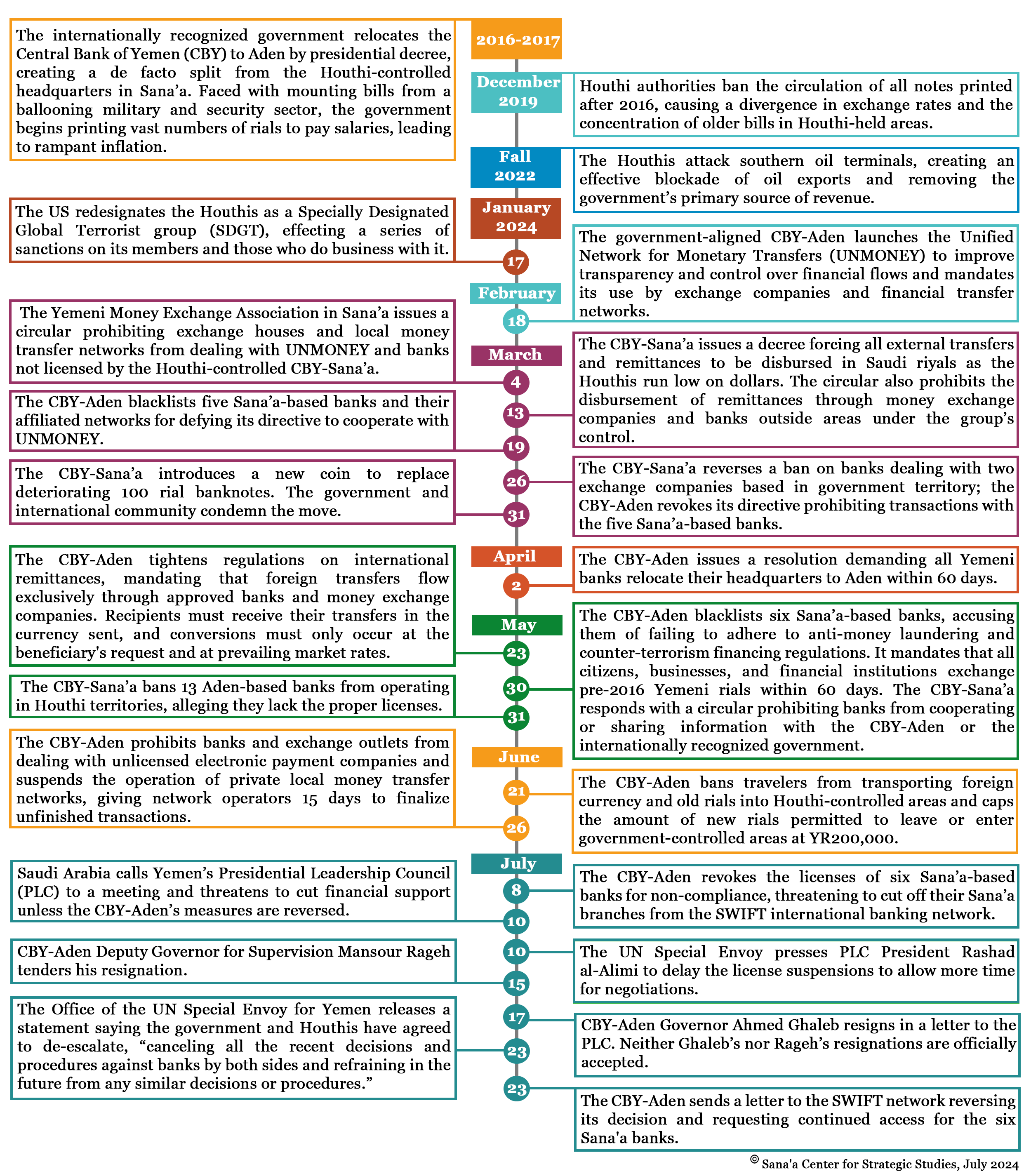

Threatened with new attacks, Saudi Arabia has forced the Yemeni government to abandon efforts to cut off the Houthi group (Ansar Allah) from the international banking system. Financial sanctions enacted by the government-aligned Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) were perhaps the government’s last card in its efforts to negotiate economic relief or affect the power imbalance ahead of presumptive peace talks. Under enormous Saudi pressure, Yemen’s Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) canceled measures to consolidate control of the banking sector and financially isolate the Houthi-held north. The CBY-Aden’s position quickly became untenable without political support, and it has been forced to reverse course. The UN Special Envoy’s Office (OSESGY) has now announced that the government and the Houthis have agreed to de-escalatory measures, including the repeal of banking and financial sanctions, and to forgo similar actions in the future.

The long-running regulatory war between Yemen’s rival central banks came to a head on July 8, when the CBY-Aden revoked the licenses of six banks,[1] threatening to cut them off from the SWIFT international banking system. The move was the culmination of a series of measures the CBY-Aden had undertaken with government support in an attempt to wrest control of the national financial system. Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi responded in two public addresses, threatening to resume attacks on Saudi Arabia if the kingdom did not intervene and to target Yemeni ports and airports if the government did not back down.[2] Riyadh had been seemingly content to remain on the sidelines as Yemen’s economic war escalated, but it moved quickly once its own interests were at stake.

A regulatory squabble may seem an unlikely catalyst for the threatened renewal of violence between the Houthis and Saudi Arabia, who remain publicly committed to a peace deal. But much is at stake, and an acute crisis has been brewing since February (see timeline). Political violence in Yemen has declined dramatically since an April 2022 truce, but economic warfare between the Houthis and the internationally recognized government has escalated substantially. The Houthis blockaded hydrocarbon exports with attacks on southern oil terminals in late 2022 and have captured customs revenues after restrictions were eased on the port of Hudaydah. The government has been pushed to the brink of bankruptcy and is now wholly dependent on Saudi grants. In response, the CBY-Aden sought to wrest control of the financial system, leveraging international sanctions and access to the SWIFT banking network in an attempt to pressure the Houthis into making concessions. In particular, the central bank hoped to broaden the financial dispute to negotiate the resumption of oil and gas exports – once the government’s primary source of revenue.

The CBY-Aden’s threat to cut off banks and financially isolate the Houthi-held north carried significant weight in the current economic environment. The economic deterioration wrought by a decade of war has taken a severe toll across the zones of control. The Houthis are facing a long-term liquidity crisis. Public sector salary payments in Houthi-controlled areas are years behind, and dissatisfaction with their suspension fueled rare protests last fall. The Houthis’ redesignation by the US as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist group (SDGT) and the group’s international pariah status complicate its financial access. Yemen is highly reliant on imports and remittances, and any interruption to cash flows or trade financing would be highly consequential. The Houthis also field a massive army, which has swollen with new recruits since the Gaza war began. The group extracts significant resources through taxation and remittance fees simply to feed its troops. In this context, isolating banks and restricting money transfers was a genuine threat to cripple the economy and destabilize Houthi control, and the policy has always carried the risk of military escalation.

It was not a risk Riyadh was willing to take. According to sources who spoke with the Sana’a Center on condition of anonymity, Saudi Ambassador Mohammed al-Jaber pulled out all the stops to coerce the government to backtrack. After a series of threats and enticements failed to move defiant CBY-Aden Governor Ahmed Ghaleb, Al-Jaber made clear the stranglehold that Riyadh holds over the PLC, summoning them to a meeting and threatening to cut off funding for the government entirely unless the CBY-Aden’s measures were reversed. Fuel grants, cash deposits, and development aid would all be canceled. He further implied that if the Houthis retaliated against the government militarily, they would be left to their fate.

Saudi instrumentalization of Yemeni politics has been a defining feature of the war. The council rapidly acquiesced to the demands, laying bare the fiction of its legitimacy as an independent government. Had it stood firm, it is not clear how far the Saudis would have gone. Al-Jaber leads the kingdom’s peace talks with the Houthis and has overseen a series of concessions to appease the group. If Riyadh saw the choice as the government’s security against its own, it might well have made good on its threats. The disconnect between Saudi and Yemeni priorities was made explicit by Al-Jaber, who reportedly told the PLC that “the bank’s decision represents a declaration of war, and no one is ready for that.” The Saudis may have concluded their active role in the conflict, but in Yemen, the fighting and suffering have not stopped.

UN Pushes for Deescalation

The Houthis initially rebuffed UN efforts to mediate, but the Special Envoy’s Office sent a letter to PLC chief Rashad al-Alimi, urging him to delay the central bank’s decision. The involvement of the OSESGY highlights a vital aspect of the crisis, which should not be lost in the political brinksmanship: the economic and financial division of the country will have serious and potentially devastating costs. Cutting off banks and money exchanges from international systems would negatively impact businesses and remittances. The economy has been crippled by a decade of conflict, and further stressors could have severe humanitarian consequences, not least by hampering the ability to disburse assistance. Yemen already operates two exchange rates, and while the continued bifurcation of the banking system and institutions of state may ultimately be inevitable, it will also be exceptionally painful. The UN has made efforts to ameliorate economic fragmentation, working to harmonize commerce rather than weaponize it. Furthermore, the Saudi road map is still the only game in town with regard to peace talks, and both sides have now signaled their recommitment to the plan. Whether or not the UN was instrumentalized by Riyadh to provide political cover, it was always likely to oppose further escalation.

The episode partly recalls the problematic UN-brokered 2018 Stockholm Agreement, which halted a UAE-backed advance up the west coast over concerns about aid flows through the port of Hudaydah. Yemen’s precarious humanitarian situation fueled fears that the port’s closure would plunge the country into famine. But a withdrawal agreement was never fully implemented, and the Houthis retained full control of the port, which is now used to smuggle weapons and facilitate naval attacks against commercial shipping. The risk of famine and humanitarian fallout should never be minimized, but it must be balanced against longer-term considerations of conflict outcomes and the suffering they produce. All coercive action carries risk. As the government side is able to be dissuaded from escalation, it has now twice been forced to abort attempts to rebalance power in Yemen. The Saudi-led coalition and the international community have been unsuccessful in extracting similar forbearance from the Houthis. The result is an amplification of the power disparity between the sides.

Government Weakness Exposed

The central bank crisis lays bare a number of political realities in Yemen, none of which augur well for a negotiated settlement. The first is Saudi Arabia’s near-complete dominance of Yemeni politics. The PLC was hand-picked by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and the government has been dependent on their support throughout the conflict. But with its revenues cut off, the government has repeatedly flirted with insolvency and now relies entirely on Saudi money to pay salaries, provide essential services, and stabilize the currency. The necessary result of this dominance is the subversion of the government to Saudi interests and policy objectives. Riyadh has been transparent about its desire to make a deal and leave the Yemeni quagmire, seemingly at any cost. Having come this far, it will not jeopardize its exit. Riyadh has intentionally kept the PLC weak and incapable of putting significant pressure on Houthi forces. When the government mobilized the last piece of leverage it held – international recognition of its financial regulatory authority – this, too, was neutralized by the Saudi threat of abandonment, and the collapse and chaos that would necessarily follow.

The government’s retreat has also made clear the incredible leverage the Houthis now wield. The group controls a majority of Yemen’s population, including the capital Sana’a. They retain military supremacy, uncowed by years of airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition and undeterred by US, British, and EU efforts to counter drone and missile attacks against commercial shipping. With the government entirely beholden to Saudi Arabia, and seemingly no limit to Riyadh’s concessions, the Houthi leadership is in the unique position of being able to dictate both sides of the conflict. It is free to wage military and economic warfare, and then to insist that the government not retaliate. Meanwhile, frontlines in Yemen remain active, and there is serious concern that the group could press their growing advantage in another bid to wrest control of the strategic oil and gas fields outside Marib.

The way forward is unclear. Both Riyadh and the PLC have been humiliated. With Yemen’s independence sacrificed on the altar of Saudi security concerns, any negotiated settlement to the conflict will need to accommodate both the dramatic power imbalance and the kingdom’s other priorities. The situation in Riyadh is reportedly tense. After its rapprochement with Iran, Saudi Arabia is hoping to secure a formal defense agreement with the US in exchange for the normalization of relations with Israel. US security guarantees could conceivably give it a stronger hand in talks with the Houthis, but America’s inability to suppress attacks in the Red Sea and recent Israeli airstrikes on Hudaydah complicate matters. Riyadh appears to be waiting for the war in Gaza and associated regional violence to play out before it restarts the peace process, with Yemen meanwhile condemned to economic and military purgatory.

The United Arab Emirates, Riyadh’s junior coalition partner, has been notably absent from the crisis. Abu Dhabi previously rejected overtures to join Saudi-Houthi talks, seemingly content to support its proxy forces in the south and await a potential division of the country. Emirati-backed PLC members Tareq Saleh and Aiderous al-Zubaidi have made clear that their respective parties support the central bank’s policies, even if they fell in line with Riyadh as part of the council. Other political parties have also made public their approval of the bank’s stance, particularly Islah, and popular demonstrations have condemned the UN for intervening. The tenuous legitimacy of the PLC has been further undermined, and its apparent betrayal of the central bank will only deepen fissures in the government camp.

The Future of the Central Bank

For the CBY-Aden, the government’s capitulation to Saudi coercion represents a catastrophic surrender. In effect, it has relinquished its autonomy as the internationally recognized monetary authority in Yemen. Internally, the CBY-Aden’s image as a credible financial institution will deteriorate, and its regulatory power diminish, emboldening war profiteers and black market operators. Externally, its global recognition as Yemen’s central bank will be irrevocably undermined. According to the OSESGY’s statement, the agreed climbdown could go far beyond the six sanctioned banks, dismantling the entire regulatory framework the CBY-Aden has painstakingly built since February.

CBY-Aden Governor Ghaleb’s unprecedented resolve in the face of government and Saudi pressure has won him widespread praise in Yemen, and he reportedly still enjoys the backing of the central bank’s board of governors. But he has now tendered his resignation, as has his deputy, Mansour Rageh, who recruited much of the bank’s technical team. Their resignations are unlikely to be accepted – their departure would further damage the central bank’s credibility and independence, which already lie in tatters. Regardless of whether they go, the damage to the bank’s reputation has been done. Its authority could yet be further curtailed in favor of the Saudi-picked Economic Committee, nominally set up to advise the PLC but operationally an instrument of Saudi oversight.

The unraveling of the central bank’s gambit speaks directly to the lie at the heart of Saudi interference. Riyadh has long wanted to cast itself as a mediator of the conflict rather than a primary belligerent, but its ontological confusion does Yemen no favors. Riyadh has lost in Yemen, and the losing side can neither act as an effective mediator nor dictate the terms of peace. The Saudis may believe they have orchestrated a climbdown in the banking crisis and preserved the status quo, but in effect, they have made further concessions, agreeing to insulate the Houthi regime from financial pressure and isolation. The war is not over, but Riyadh is now actively playing both sides. Unless and until the Saudis, the UAE, or the international community can summon the resolve to condition Houthi behavior or incentivize the group’s commitment to a negotiated political settlement, we should expect the fighting to go on, and for the Houthis to keep winning.

This analysis was produced as part of the Applying Economic Lenses and Local Perspectives to Improve Humanitarian Aid Delivery in Yemen project, funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

- The six banks were the Tadhamon International Islamic Bank, Yemen Kuwait Bank, Yemen and Bahrain Shamil Bank, Al-Amal Microfinance Bank, Al-Kuraimi Islamic Microfinance Bank, and International Bank of Yemen.

- Editor’s note: Abdelmalek al-Houthi’s public statements only threatened Saudi Arabia, as he does not openly acknowledge the internationally recognized government. Threats to Yemeni air and sea ports were made through private channels.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية