Executive Summary

Foreign actors have a long history in Yemen. From the first Zaidi imam who arrived in the country in the ninth century to the regional military intervention led by Saudi Arabia in 2015, outsiders have often altered the trajectory of domestic politics in Yemen. This has been particularly pronounced throughout the 20th century, when modern communication technology, speed of travel and air power allowed outside powers, such as the British empire in south Yemen, to more directly influence and impact change on the ground in Yemen. But perhaps never have foreign actors had as large and influential a role in Yemen as they do in the midst of the ongoing war.

Not surprisingly, given its proximity to Yemen and relative wealth, Saudi Arabia plays an outsized role in the internal affairs of its southern neighbor. The kingdom has twice supported the losing side in Yemeni civil wars, backing the royalists in the 1960s and the southern secessionists in 1994. Saudi Arabia’s economic influence has similarly cast a long shadow over Yemen. In 1990, Saudi Arabia expelled nearly 1 million Yemeni migrant workers in retribution for then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s stance on then-Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. The exodus of Yemenis from Saudi Arabia and the lack of migrant remittances crippled Yemen’s economy and, in many ways, it never recovered. Saudi Arabia also instituted checkbook diplomacy, making direct payments to politicians and tribal leaders as a way of maintaining influence over politics in Yemen.

More recently, Saudi Arabia – a hereditary kingdom – took the lead in overseeing Yemen’s democratic transition from Saleh’s rule in the wake of the Arab Spring. Three years later, in 2015, Saudi Arabia felt compelled to intervene militarily in Yemen in an attempt to restore the internationally recognized government of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi. A war Saudi Arabia thought would last six weeks has now lasted six years, with no end in sight. In many ways, Yemen is much more divided in 2021 than it was in 2015. It is far from certain whether Yemen will be reconstituted as a single state in the near- to medium-term future.

Along with Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran, all of whom have played outsized roles in Yemen’s recent history, the United States remains a key actor both for what it has done in Yemen as well as what it left undone. For the past two decades, the United States has carried out unilateral attacks against what it describes as terrorist targets in Yemen. It has also played a key role diplomatically, teaming with Saudi Arabia to punish Yemen for Saleh’s ill-conceived “no” vote in the UN Security Council in 1990 to actively pressing the “Gulf Initiative” in 2011 that led to Saleh stepping down in exchange for immunity. More recently, the United States has backed the Saudi-led coalition’s military intervention in Yemen, providing logistical and intelligence support, even as the US maintains that it is not a party to the conflict. Perhaps more importantly, the United States has failed to use its diplomatic influence with Saudi Arabia to influence or change the current trajectory of the war.

Given the current realities on the ground as well as the numerous foreign actors involved in the current conflict, Yemen is unlikely to be able to chart its own course in the near future. This paper does not propose a solution to the current predicament. Rather, it explains how Yemen got to this point by illustrating the roles and interests of Yemen’s many foreign actors.

Acknowledgments

The Sana’a Center wishes to thank the following individuals for their contributions and insights during a series of virtual roundtables in 2020:

Imad Al Akhdar, Ali Al-Dailami, Maysaa Shuja Al-deen, Tawfeek Al-Ganad, Abdulghani Al-Iryani, Dr. Mohammed Al-Kamel, Hisham Al-Khawlani, Jay Bahadur, Anthony Biswell, Laura Kasinof, Helen Lackner, Nisar Majid, Ahmed Nagi and Hussam Radman.

No one individual is likely to agree with all of the below, nor are any of these individuals responsible for the views expressed in this paper. However, all of them graciously gave of their time and expertise to benefit this project. We are thankful to all of them. All views and any errors remain those of the author alone.

Table of Contents

- Saudi Arabia: A Benefactor Who Sets the Rules

- The UAE: Saudi Arabia’s Partner and Rival

- Oman: A Neutral Mediator Not Immune to Criticism

- Qatar: Often a Thorn in Riyadh’s Side

- Kuwait: A Willing Host

- Iran: Growing Closer to the Houthis as War Stretches On

III. Yemen and the Broader Muslim World

- The Israel-Palestine Conflict

- The Gulf Crisis and Iraq

- Afghanistan and Al-Qaeda

- The Islamic State Group and the Start of a Jihadi Rivalry in Yemen

- The Muslim Brotherhood

- Hezbollah, a Friend and Ally of the Houthis

IV. Yemen and the Horn of Africa

- The United States: Yemen as a Security Problem to be Managed

- The United Kingdom: A Colonial Power that Wields the Pen

- Russia: A Silent Actor

- China: The Building Contractor

VI. Yemen and Global Financial, Economic Powers

VII. Yemen and the United Nations

Introduction

Modern Yemen exists in the shadow of its wealthier, more powerful neighbors. Frequent conflict in the 20th and early 21st centuries – competing civil wars in the 1960s, again in 1986, 1994 and, most recently, in 2014 – along with perceptions of instability have drawn in an array of outside powers, from Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom in the 1960s to the United States in the aftermath of the Al-Qaeda attacks on the USS Cole in 2000 and New York and Washington on September 11, 2001. Yemen has often been seen as a threat to itself, its neighbors and even the world, and this understanding has shaped and colored the responses of various foreign actors.

This survey takes in the breadth of outsiders in Yemen, ranging from the first Zaidi imams who came to Yemen in 893 to the Colombian mercenaries that the United Arab Emirates imported in 2015. Yemen has not always responded wisely or even coherently to outside events. For instance, former President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s disastrous decision to support Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 hobbled the newly unified country before it could even get out of the gate. But if Yemen has, at times, struggled to understand the outside world, so, too, has the world often been plagued by its inability to see Yemen clearly. Empires – the Ottomans and the British – have been chased from the country, regional powers have been sucked into conflicts and superpowers have felt forced to intervene. Yemen’s history, as varied as it has been, has a single constant: foreign actors.

I. Historical Background

In 893, tribes in the Sa’ada region summoned Yahya bin Hussein from what is now Saudi Arabia to mediate between warring tribes in Yemen. Despite some initial setbacks, Yahya, who would later be known by the honorific Imam Hadi ila al-Haqq, or the “one who leads to truth,” eventually established the first Zaidi imamate in north Yemen. For the next 1,000 years, the power of the Zaidi imams waxed and waned but never disappeared.

The Ottomans invaded north Yemen in the 16th and 17th centuries, before a pair of invasions in the mid- and late-18th century finally allowed them to take control of Sana’a. In 1904, a local rebellion by a young Zaidi who claimed the title of the imam, Yahya bin Mansur Hamid al-Din, was eventually successful and established the Hamid al-Din dynasty, which ruled north Yemen until the palace coup of 1962.

A British marine detachment landed at Aden in 1839, eventually establishing the Aden protectorate and later the crown colony at Aden. British influence moved inland throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, although Aden and its port, midway between India and the Suez Canal, was always key. In the mid-20th century, the port at Aden was the third-busiest in the world.[1]

In the span of two years in the early 1960s, uprisings broke out in both north and south Yemen that would lead to lengthy civil wars. In the north, a palace coup on September 26, 1962, against Mohammed al-Badr Hamid al-Din, who had been in power only a week following the death of his father, sparked an eight-year civil war. Within days, Egyptian troops dispatched by Gamal Abdel Nasser landed in Sana’a in an effort to defeat those who eventually became known as the “Royalists” and to establish a modern Arab republic along Egyptian lines.[2] Saudi Arabia, Britain, Jordan and a host of other countries backed Mohammed al-Badr. But the Royalists were never able to recapture Sana’a, even after Egypt withdrew in the wake of the Six-Day War in June 1967. By 1970, the war was over and the Yemen Arab Republic had replaced the Zaidi imamate in the north.

In southern Yemen, the fighting started as an anti-colonial war against the British in Aden, but eventually broke down into a struggle for power among various leftist groups. Britain withdrew from Aden in 1967, and three years later the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) was formed. Over the next two decades, the PDRY was deeply dependent on foreign aid from the Soviet Union and often struggled with internal divisions, including a brief but incredibly bloody battle for control of Aden in 1986 in which thousands were killed.[3]

In the republican north, politics were similarly violent. The first two presidents of the republic – Abdullah al-Sallal and Abd al-Rahman al-Iryani – were both overthrown in coups in 1967 and 1973, respectively. The next two presidents, Ibrahim al-Hamdi and Ahmad al-Ghashmi, were assassinated within nine months of one another, which allowed a relatively unknown military officer named Ali Abdullah Saleh to become president of north Yemen in 1978. Saleh quickly restructured Yemen’s military and security apparatus, empowering relatives and trusted clansmen of his Sanham tribe by giving them top military commissions or their own security forces.[4] In later years, Saleh liked to point out that the CIA didn’t think he’d last six months, and he’d made it more than three decades.[5]

Unity and Division: 1990 – 2010

In 1990, driven by the discovery of oil and the collapse of the Soviet Union, north and south Yemen agreed to unify. This marriage of the “two Alis” as it was sometimes called – Ali Abdullah Saleh in the north and Ali Salem al-Beidh in the south – did not go well. Both sides attempted to undermine and weaken the other. Saleh invited back tribal families that had lost land during the socialist redistribution in the 1960s and 1970s as well as former jihadis who had fought the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s, explaining that he, too, was battling communists.[6] In 1994, the sniping erupted into a civil war when the south attempted to secede. Saudi Arabia backed the secession attempt, but Saleh, with help from former jihadis and the Islamist party Islah, was able to put down the secession attempt within weeks.

Saleh named Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, a southerner from Abyan who did not support secession, as his vice president. In an effort to ensure that his rule was not challenged in the future, Saleh also began working to weaken groups such as Islah, which had been instrumental in helping him to victory in the civil war. Saleh liked to play his domestic rivals off against one another, a form of governing he often referred to as “dancing on the heads of snakes.”[7] Other scholars, such as Sarah Phillips, have referred to this as the “politics of permanent crisis.”[8]

In the aftermath of the 1997 parliamentary elections, worried that Islah was growing too strong, Saleh began backing a number of domestic rivals to Islah, including the traditionalist Zaidi political party, Hizb al-Haqq (Party of Truth). This included providing direct payments to Zaidi leaders such as Hussein Badr al-Din al-Houthi,[9] who was a member of parliament for Hizb al-Haqq from 1993-97, as well as giving Zaidi loyalists control over coveted ministries such as the Ministry of Education. Saleh’s payments were known locally as ‘itimad (support). Hussein al-Houthi used this money to finance his studies for a Master’s degree in Sudan in 1999 and 2000.

But by 2000, the political winds had shifted again, and Saleh cut his payment to Hussein al-Houthi. The former member of parliament returned to Yemen and his home in Sa’ada, where he began reconnecting with members of the Shabab al-Muminin (The Believing Youth), a loose affiliation of Zaidi revivalist students, which had formed in the 1980s initially as summer camps to promote traditional Zaidi teachings, and which the community felt were under threat from the import of both Salafism and Sunnism in general.[10] The Believing Youth had been founded by Mohammed Izzan and Mohammed Badr al-Din al-Houthi, one of Hussein al-Houthi’s half-brothers, and would later form the nucleus of the Houthi movement known today as Ansar Allah.

Saleh first became aware of the fledgling Houthi movement in 2002 on a trip to Saudi Arabia, when Houthi supporters rallied against him outside a mosque in Sa’ada. Two years later, in June 2004, Saleh had had enough, and he instructed the governor of Sa’ada to arrest Hussein al-Houthi.[11] Hussein resisted and the first of what would become six Houthi wars began.

Yemeni troops killed Hussein al-Houthi in September 2004, ending the first war. Hussein’s father, Badr al-Din al-Houthi (d. 2010), assumed leadership of the movement before Hussein’s younger half-brother, Abdelmalek, became the group’s leader. War blended into war as successive cease-fires between Saleh’s government and the Houthis never quite held. The sixth war began in November 2009 and, for the first time, spilled over into Saudi Arabia.[12] The war ended in early 2010, months before the Arab Spring protests would begin in Tunisia before reaching Egypt and, later, Yemen. There is little evidence to suggest that at this point the Houthis were receiving any material support from Iran.[13] It is likely, however, that the Saudi military’s poor performance against the Houthis in late 2009 attracted Iranian attention.

At the same time Saleh was dealing with the Houthi insurgency in the north and a renewed Al-Qaeda threat in the country, he was also struggling to contain a third threat. In 2007, more than a decade after the 1994 civil war, former southern soldiers who had been decommissioned and stripped of their pensions began protesting Saleh’s rule and domination of the south. This loose coalition became known as the Southern Movement. The combination of these three threats to Saleh’s rule, along with intra-elite rivalries over succession and falling oil [14] made Saleh particularly vulnerable to popular protests in 2011. As Yemen collapsed in on itself in the early part of the 2010s, it invited more outside interventions from foreign actors.

II. The Gulf

Saudi Arabia: A Benefactor Who Sets the Rules

Saudi Arabia is perhaps the most important foreign actor in Yemen. The kingdom has a long and complicated history with its southern neighbor. In 1934, Abdul Aziz ibn Saud and Imam Yahya went to war. Ibn Saud’s troops crushed the imam’s soldiers, who were under the command of his eldest son and heir apparent, Ahmed. Saudi Arabia managed to secure three provinces – Najran, Asir and Jizan – which had been under the control of the imam. The subsequent border dispute simmered for decades, and it wasn’t until 2000 that the border lines between Yemen and Saudi Arabia were officially demarcated.

In the 1960s, as detailed above, Saudi Arabia supported Imam Yahya’s grandson and heir, Mohammed al-Badr, in the civil war against the Republicans and their Egyptian backers. Indeed, Saudi Arabia has largely seen Yemen, throughout the latter half of the 20th century and the first part of the 21st, as within its sphere of influence; it has reacted strongly to any presence, perceived or real, of outside rivals, whether with Egypt in the 1960s or Iran this past decade.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s as Saudi Arabia welcomed Yemeni migrant workers into the kingdom, it also began sending back proselytizing Sunni missionaries.[15] This fit the republican model, which was looking to erode the power of traditional Zaidism. The kingdom also set up a Special Committee for Yemen Affairs, which coordinated Saudi Arabia’s policy and frequently made direct payments to tribal sheikhs across northern Yemen. Perhaps the most important of these was Abdullah al-Ahmar, paramount sheikh of the Hashid Tribal Confederation.[16]

Following the unification of North and South Yemen in 1990, Saudi Arabia grew increasingly concerned about the presence of a functioning parliamentary democracy on the Arabian Peninsula. Most notably, Saudi Arabia expelled nearly 1 million Yemeni migrant workers in retaliation for Saleh’s positions on Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, as detailed below. In time, workers began returning, and in 2020 there were 2 million Yemenis working in Saudi Arabia, sending much-needed remittances home to their families.[17] Saudi Arabia’s ideal southern neighbor would be a Yemen that was weak enough that it couldn’t challenge the kingdom but not so weak that it presented a risk of continuous instability along the Saudi border. This understanding of Yemen likely contributed to Saudi Arabia’s support for southern secession in 1994.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), of which Saudi Arabia was the leading voice, held out the possibility of provisional membership to Yemen. But this never materialized. Yemen, unlike the other six members of the GCC, was both poor – in 2010 Yemen was rated the poorest country in the Arab world[18] – and populous, with an estimated 27 million people.

In 2009, Saudi Arabia was drawn into two of Yemen’s three internal crises: the war against Al-Qaeda and the Houthi wars. First, in August 2009, a Saudi member of AQAP, disguising himself as a repentant jihadi looking to turn himself in, nearly assassinated Mohammed bin Nayef, the then-deputy minister of the interior and a member of the royal family.[19] Bin Nayef sustained injuries in the attack, which were later used by his rival within the royal family, Mohammed bin Salman, to cast aspersions on Bin Nayef’s ability to rule.[20]

A few months after the assassination attempt, in November 2009, Saudi Arabia’s military was sucked into Saleh’s war against the Houthis in Sa’ada. As mentioned above, Saudi’s military performed particularly poorly during a number of clashes in late 2009. At the time, the Houthis uploaded several videos to YouTube showing barefoot fighters from Yemen overrunning Saudi military camps and seizing Saudi military vehicles, munitions, and supplies. Saudi Arabia, which spends billions per year on its military,[21] was embarrassed that a poorly trained and poorly armed tribal militia was able to so easily defeat its border defenses. The desire for revenge against the Houthis may have been a factor in Saudi Arabia’s decision to go to war in Yemen five years later in March 2015.

Prior to that, however, Saudi Arabia played a key role, along with the United States, United Nations and GCC, in facilitating the deal that saw Saleh step down from power in February 2012. Saudi Arabia provided the initial medical attention to Saleh following the unsuccessful assassination attempt in June 2011. The kingdom subsequently used much of its diplomatic and economic muscle to ensure that Saleh, indeed, stepped down from power, the optics of a monarchy overseeing a political transition in an ostensible democracy notwithstanding.

The Saudi-led Intervention

In March 2015, after President Hadi escaped from house arrest in Sana’a and fled first to Aden and then to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia announced that it was leading a coalition to expel the Houthis from Sana’a and restore Hadi to power.[22] Interestingly, Saudi Arabia announced Operation Decisive Storm from Washington instead of from Riyadh,[23] signaling the importance of US buy-in to Saudi Arabia’s military strategy. That same evening, the US announced the formation of a joint US-Saudi intelligence cell, which would be based in Riyadh.[24]

In order to get the US to acquiesce to Operation Decisive Storm, Saudi Arabia told US government officials that the war to expel the Houthis from Sana’a would take about “six weeks.”[25] This obviously turned out to be wildly off the mark. Saudi Arabia very quickly established air dominance over Houthi-controlled areas of the country, and helped push them out of Aden and back north, but air power alone proved unable to uproot the Houthis from Sana’a.

Saudi Arabia’s decision to go to war in Yemen in 2015 was largely driven by its worry that the Houthis would act as an Iranian proxy,[26] similar to Hezbollah, on its southern border. This, however, was likely a mistaken understanding of Iranian-Houthi relations in late 2014 and early 2015. At the time, as explained below, the Houthis and Iran had a weaker relationship than Saudi Arabia believed. Indeed, in many ways, Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen has become a self-fulfilling prophecy, driving the Houthis and Iran closer together.

Saudi Arabia’s air campaign in Yemen quickly eliminated what known military targets existed. Poor training, concerns over anti-aircraft fire, and a pervasive lack of concern within the Saudi air force led to high numbers of civilian casualties in Yemen.[27] Within a year of launching Operation Decisive Storm it became apparent that Saudi Arabia had three main military options in Yemen. It could continue with its air campaign and hope something changed on the ground. It could insert ground troops for what would likely be a long and bloody ground war with no guarantee of success. Or, it could withdraw and allow the Houthis to claim victory and remain in Sana’a.

Not surprisingly, Saudi Arabia chose the first option: continue carrying out air strikes in the hopes that something on the ground would change. That has largely not happened, at least not in a way that would benefit Saudi Arabia’s military goals. Saudi Arabia began heavily restricting imports into northern Yemen shortly after its military intervention began. However, Riyadh implemented what amounted to a full economic blockade of Yemen in November 2017, temporarily closing all land, sea and air ports in an attempt to spark internal unrest in Houthi-controlled territory that would lead to a popular uprising.[28] Like much of Saudi Arabia’s recent policy in Yemen, this was a miscalculation, as many in Houthi-controlled territory were willing to give the Houthis’ poor record of governance a pass so long as Saudi Arabia continued its largely indiscriminate air campaign. In other words, the blame for poor living conditions in Yemen more often fell on Saudi Arabia than on the Houthis. Ultimately, the UN Panel of Experts alleged that Saudi Arabia was using “the threat of starvation as an instrument of war.”[29]

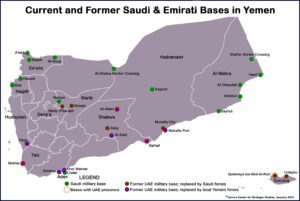

In 2019, Saudi Arabia’s main partner in the war in Yemen, the United Arab Emirates, announced a significant drawdown of troops from Yemen. Saudi Arabia moved its troops into many areas of the country, such as Aden and Marib, to replace departing Emirati ones. However, within months, fractures in the anti-Houthi alliance quickly became apparent and, in the south, led to open fighting between troops loyal to President Hadi and those affiliated with the Southern Transitional Council (STC), which advocates for an independent state in southern Yemen.

Much of Saudi Arabia’s efforts over the past year, from late 2019, have been directed toward papering over the differences within the anti-Houthi alliance through arrangements such as the Riyadh Agreement, which aims to incorporate pro-STC militias into the government forces and to provide space for southern secessionist politicians within the Hadi government. Despite massive Saudi pressure for Hadi’s government and the STC to get along and present a unified front against the Houthis, implementation of the Riyadh Agreement has been sporadic.[30]

Although Saudi Arabia has not yet lost the war in Yemen, it almost certainly cannot win it. The Houthis remain in control of large portions of the north, effectively functioning as a nation state, and six years of a devastating air campaign has done little to limit – and likely has increased – both the Houthis’ hold on power as well as the group’s closeness to Iran.

The UAE: Saudi Arabia’s Partner and Rival

The United Arab Emirates is Saudi Arabia’s primary partner in the war in Yemen. But from the very beginning, Saudi Arabia and the UAE appeared to be pursuing different policies in Yemen. Saudi Arabia, which was worried about a Hezbollah-like group on its southern border, focused on combating the Houthis. The UAE, on the other hand, focused much of its efforts on creating and equipping effective proxies and concentrating militarily along Yemen’s coastlines and on the island of Socotra.

The UAE, at least initially, had more troops – both UAE soldiers as well as contractors and mercenaries[31] – involved in active combat in Yemen than did Saudi Arabia. On September 4, 2015, UAE forces experienced their deadliest day when 45 Emirati soldiers were killed by a Houthi missile strike on a weapons depot in Marib.[32] This attack and the Emiratis’ leading role on the ground may have contributed to UAE decisions about forming and funding proxy units in Yemen that operated outside the control of Hadi’s government. The first of these groups were formed in late 2015 and early 2016, initially as a way to combat the Houthis and Al-Qaeda. In Hadramawt, the UAE backed the Hadrami Elite forces, which helped push Al-Qaeda out of the port city of al-Mukalla in 2016.[33] Around the same time, the UAE also formed the Shabwani Elite forces in neighboring Shabwa, and the Security Belt forces, which were designed to protect Aden.

The STC, which formed a year later in 2017, aligned itself with the UAE. Both have a shared interest in opposing Islah and the Muslim Brotherhood. Indeed, over the past three years, UAE-founded and -funded proxies have effectively formed the STC’s military. There are, however, a few notable exceptions, including the largely Salafi Giants Brigade as well as Tariq Saleh’s National Resistance Forces, both of which are close to the UAE but are not within the STC’s umbrella of support.

As Gulf analyst Thomas Juneau has pointed out, the UAE’s strategy of economic development is “premised on its position as a logistics hub for regional trade.”[34] This makes maritime security essential, particularly “in the U-shaped area around the Arabian Peninsula encompassing the Persian Gulf, the Arabian and Oman seas, the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea.”[35] From this perspective, the UAE’s involvement in Yemen was part of its broader regional strategy, which included military bases and ports on both sides of the Red Sea.[36]

There are two main reasons for the UAE’s 2019 drawdown. First, the Emiratis had sufficiently established enough proxy units, often estimated at around 90,000 troops, that it could withdraw most of its own forces in Yemen and still maintain significant influence through its military proxies. The second reason, as Juneau points out, is that the UAE determined that the war in Yemen was “proving costly” not only in terms of lives lost but also diplomatically, with much of the US Congress having turned against the war.[37]

The UAE withdrew from its bases in Marib and Aden, both of which were taken over by Saudi troops. But it maintained officers at its base in Mokha, on the Red Sea Coast, where those officers now work with Tariq Saleh’s forces.[38] It also kept a contingent of soldiers in Shabwa, at Balhaf Liquid Natural Gas terminal, and Al-Alam military camp north of the governorate capital, Ataq, despite the local governor’s stated opposition to the UAE.[39]

Finally, the UAE has also remained active on the island archipelago of Socotra, where its representative, Khalfan al-Mazrouei, is instrumental in distributing aid. The UAE placed a small number of troops on Socotra in 2018, which eventually led to accusations from the Hadi government that the UAE was trying to take control of the island.[40] The UAE has also continued to recruit local Socotris for its proxy forces in Yemen and has set up facilities on the island to train new recruits in battle skills, weapons handling and first aid before sending them to the front lines.[41] More recently, in June 2020, the STC, which is backed by the UAE, took over the island of Socotra.[42] Despite this, the presence of Saudi troops on the island has acted as a deterrent to the UAE establishing a greater foothold, which could entail a permanent military presence to advance Emirati regional political and economic goals from an island strategically located on a key oil shipping and commercial trade route.

Oman: A Neutral Mediator Not Immune to Criticism

Like Saudi Arabia, Oman shares a border with Yemen. But unlike every other member of the GCC, Oman was the only country that did not initially join the Saudi-led coalition. Instead, Oman took a carefully neutral approach to the conflict in Yemen, allowing one of Saleh’s sons, Khaled, to conduct a number of financial transactions in the country even after the former president was sanctioned by the UN.[43] Oman also allowed Houthi negotiators and figures to remain in Oman and to seek medical attention there. At the same time, Oman intervened on a number of occasions to serve as a mediator, frequently convincing the Houthis to release detained foreigners in their custody.[44]

At various times in the conflict, Oman has pushed back against allegations it was allowing its territory to be used to smuggle Iranian missile components to the Houthis. Most analysts, including the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen, concur that Iranian missile components were being smuggled across the country from Al-Mahra, after entering the governorate either overland via Oman or from the sea, to Houthi-controlled territory.[45]

Despite Omani denials, Saudi Arabia has used these allegations as an excuse to build up its military presence in Al-Mahra, including along the Omani border. Over the past three years, Saudi Arabia has established a number of military installations in Al-Mahra.[46] This has elicited strong negative reactions both from local tribes as well as from Oman, which considers Al-Mahra to be within its own sphere of influence. Speakers of Mahri – a language distinct from Arabic and a descendant of Old South Arabian – exist on both the Yemeni and Omani sides of the border. To combat Saudi influence in Al-Mahra, Oman has been funding local tribes and sheikhs. Perhaps the most notable of these is Sheikh Ali Salem al-Hurayzi, a former commander of Yemen’s border guards.[47]

Qatar: Often a Thorn in Riyadh’s Side

Although initially part of the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, Qatar later withdrew from the coalition in 2017 due to its dispute with Saudi Arabia. Two years later, in 2019, Qatar pushed into the messy and multifaceted conflict in Taiz, backing senior Islah figure Hamoud al-Mikhlafi by paying his fighters. In order to disguise Qatari involvement, which was an open secret, Oman disbursed the payments.[48] Although Saudi Arabia and Qatar ended their dispute in January 2021, it is unclear to what degree this will influence their various allies on the ground in Yemen.

One theory suggests that Qatar will now be much less likely to antagonize Saudi Arabia in Yemen, which could result in cutting back its support for Islah factions in Taiz. Many of Islah’s top leaders are currently outside of the country, primarily in Riyadh, Doha and Istanbul. These locations, and the various foreign policies of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey, have impacted the conflict on the ground, as different branches of Islah have emerged: a Saudi-backed Islah, which is prominent in Marib and Taiz; and a Qatari/Turkish-backed Islah, which is present in Taiz. The Qatari-Saudi rapprochement may, then, result in a similar intra-Islah rapprochement on the ground in Yemen. Although, of course, this remains to be seen.

Another outcome of restored relations between Saudi Arabia and Qatar may be that the Doha-based Al Jazeera news channel becomes much more muted in its coverage of Saudi’s war in Yemen. Although Qatar did not close Al Jazeera — one of Saudi Arabia’s goals in the blockade — it may turn out that the local Arabic criticism that Saudi Arabia faced from its conduct in the war disappears or at least is greatly reduced.

Kuwait: A Willing Host

In 2016, Kuwait hosted extensive peace talks, which lasted for several months but were ultimately inconclusive between the Houthis and Hadi’s government. In many ways, this was the best opportunity for peace in Yemen and was supported by the UN as well as by the Obama administration. Secretary of State John Kerry made the talks a priority. However, President Hadi undermined the talks before they even got started by naming Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar as his vice president. The Houthis blame Al-Ahmar, a major general in the Yemeni army under Saleh, for much of the destruction in Sa’ada from 2004-10, and his appointment as vice president indicated to them that Hadi was not serious about peace. Kuwait has said since the 2016 talks failed that it remains a willing host.[49]

Iran: Growing Closer to the Houthis as War Stretches On

Iran’s relationship with the Houthi movement has evolved over time, and grown increasingly close since the intervention of the Saudi-led coalition in 2015. Even before this, however, then-President Saleh was making wild claims that the Houthis in Sa’ada were an Iranian proxy.[50] Mostly, this was a ploy typical of Saleh to tie domestic challenges in Yemen to larger international issues. But the US and Saudi Arabia, at least in 2009, were not buying what Saleh was selling. Indeed, in late 2009, the US Embassy in Sana’a dispatched a cable, quoting a member of Saudi Arabia’s Special Committee for Yemen Affairs, saying: “We know Saleh is lying about Iran, but there’s nothing we can do about it now.”[51]

As mentioned above, Iranian interest in the Houthis began to grow in late 2009, after the Houthis clashed with Saudi troops in the kingdom. Following those clashes, Iran positioned a ship in the Red Sea at the same latitude as the Yemeni port of Midi. Iran said the ship was to coordinate Iranian anti-pirate activity, but it was generally viewed as an off-shore intelligence gathering hub for what was happening in Yemen.[52]

During the Arab Spring protests in Yemen, Iran flew dozens of Yemeni activists – both Houthis and non-Houthis – to Tehran.[53] Later, in 2012, Iranian weapons shipments started to appear in Yemen. Perhaps the most noteworthy shipment was the Jihan-1, which was seized in a joint US-Yemen raid in January 2013.[54] The ship was carrying a significant amount of arms, including Katyusha rockets, surface-to-air missiles, Iranian-made night vision goggles, small arms suppressors, as well as C-4 explosives.[55]

Interestingly, when the Houthis took Sana’a in September 2014, the group did so against the explicit advice of Iran.[56] Iran did, however, shift its posture toward the Houthis from one of assistance and aid before the Saudi-led war began to what was essentially an alliance after March 2015. Iran began smuggling weapons and missile components to the Houthis, who utilized them to carry out strikes against Saudi Arabia.[57] As the relationship deepened over the course of the war, the Houthis even lied to provide plausible deniability to Iran. This was most obviously the case in the September 2019 Iranian attacks on Saudi oil facilities in Abqaiq, which the Houthis claimed.[58]

In August 2019, the Houthis appointed an ambassador to Iran. Just over a year later, in October 2020, Iran reciprocated by sending an ambassador, Hassan Irloo, to Sana’a, effectively recognizing the Houthis as the legitimate government of Yemen. Washington quickly imposed sanctions on Irloo,[59] alleging he and Abdul Reza Shahlai, who escaped a US drone strike in Yemen in January 2020, are officers within the Iranian military’s elite Quds force working with the Houthis.[60] After nearly six years of war, Iran and the Houthis are closer than ever, largely as a result of the Saudi-led war in Yemen.

III. Yemen and the Broader Muslim World

The Israel-Palestine Conflict

The Israel-Palestine conflict has cast a long shadow over Yemen. Shortly after the 1948 war and the establishment of the state of Israel, Imam Ahmad Hamid al-Din – Yahya’s son and Mohammed al-Badr’s father – allowed several Yemeni Jews to emigrate to Israel. Yemen has a historic Jewish community that dates back centuries, and parts of Yemen were a Jewish kingdom in the 4th and 5th centuries. In 1951, when many of these Jews wanted to return to Yemen, Imam Ahmad denied their request.[61]

In 1967, as mentioned above, Egyptian troops withdrew from Yemen following their defeat in the Six-Day War. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Palestine and Palestinians existed as a rhetorical cause in Yemen, with a full-throated defense of Palestine made easier by its distance. Following the first intifada in 1987 and unification in Yemen in 1990, Ali Abdullah Saleh welcomed emissaries and representatives from various Palestinian factions. Unlike its neighbors in the Gulf, Yemen did not contribute much financially to the Palestinian cause.

In 2000, following his return from Sudan, Hussein Badr al-Din al-Houthi was watching coverage of the second intifada on television. On September 30, video footage from Gaza showed a 12-year-old boy caught in the crossfire and crouching behind his father for protection. The boy was killed and, according to the story that has since developed, Hussein al-Houthi declared: “God is Great. Death to America. Death to Israel. Curse Upon the Jews. Victory for Islam.”[62] That slogan has since become the refrain of the Houthi movement.

The Houthis have since cracked down on Yemen’s remaining Jewish population,[63] many of whom lived in Sana’a and Sa’ada, to the point that roughly two dozen Jews remain in Yemen.[64] The Houthis, like Saleh’s government before them, have also welcomed representatives from various Palestinian organizations to Sana’a. For instance, Khalid Khalifah, the representative of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, was present at official events in Sana’a commemorating the one-year anniversary of the January 3, 2020, US assassinations of Iranian Major General Qassem Soleimani, who was responsible for regional military operations, and Iraqi militia figure Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis.

The Gulf Crisis and Iraq

In 1990, the newly unified Yemen was given the so-called “Arab seat” on the UN Security Council. Later that year, in August, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. Then-President Saleh quickly found himself in an untenable situation. He liked the Iraqi strongman and considered him a friend. But Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United States were all pressing for Yemen’s vote in the Security Council.

Saleh abstained from the initial UN Security Council resolution, UNSCR 660, in August condemning Iraq’s invasion. Three months later, in November 1990, US Secretary of State James Baker visited Yemen to campaign for Saleh’s vote in the Security Council. By that point, passage of the resolution was assured, but the United States and President George H.W. Bush wanted a united front for the first post-Cold War conflict.[65]

Saleh refused to commit to a ‘yes’ vote on what would eventually become UN Security Council resolution 678, which was used to authorize Operation Desert Storm. Baker later told Yemen’s ambassador to the UN that voting against the resolution would “be the most expensive ‘no’ vote you ever cast.”[66] The US, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia cut off aid; the kingdom also expelled nearly a million migrant workers whose remittances had supported Yemen’s economy. The Yemeni rial lost half its value, and Yemen “found itself diplomatically isolated and in the midst of an economic crisis.”[67]

Afghanistan and Al-Qaeda

Like many Middle Eastern countries, North Yemen encouraged young men to travel to Afghanistan throughout the 1980s to participate in the war against the Soviets.[68] However, unlike leaders of many of those countries, Saleh welcomed the so-called Afghan Arabs back. Much of this, as discussed above, was the result of Saleh’s desire to undermine and weaken his socialist rivals following unification in 1990. One of the most prominent of these Afghan Arabs was Tariq al-Fadhli, whom Saleh utilized to wage a guerrilla war against the Yemeni Socialist Party in southern Yemen from 1990 to 1992.[69]

In December 1992, former Afghan Arabs connected to Osama bin Laden carried out a terrorist attack on two hotels in Aden, which they mistakenly believed were housing US troops who were using the city as a staging ground for Operation Restore Hope, a multinational effort to secure humanitarian aid routes in Somalia. Many analysts believe this was Al-Qaeda’s first terrorist attack.[70] Saleh later utilized many of these Afghan Arabs – although not Al-Fadhli, who was under loose house arrest for his role in the 1992 bombings – during the civil war against the socialists and Al-Beidh, the southern leader, in 1994.

Over the next six years, Yemen emerged as a safe haven for Al-Qaeda operatives as bin Laden moved from Saudi Arabia to Sudan and eventually to Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda attempted to bomb a US warship while in Aden’s port, the USS Sullivans, in January 2000, but that plot failed when the motorized skiff sank under the weight of the explosives.[71] Ten months later, in October 2000, Al-Qaeda succeeded with a similar attack, bombing the USS Cole as it was being refueled in Aden, and killing 17 US sailors.

Following the September 11, 2001, attacks in the US, Yemen emerged as a frontline in the US war against Al-Qaeda. In November 2002, the US carried out its first drone strike outside an active battlefield in Yemen, killing Abu Ali al-Harithi, who was suspected of planning the USS Cole attack,[72] as well as a handful of other Al-Qaeda suspects, including Kamal Darwish, a dual US-Yemeni citizen.[73] However, within two years of the strike, Yemen had cracked down on Al-Qaeda and the organization, partly as a result of arrests and partly due to the attraction of fighting US forces in Iraq, had all but ceased to exist in Yemen.

From 2004-2006, there was almost no Al-Qaeda activity in Yemen. But in February 2006, following a disastrous state visit by Saleh to Washington in which he was told Yemen was losing significant amounts of US aid, 23 Al-Qaeda suspects tunneled out of a prison in Sana’a. Two of the escapees, Nasir al-Wuhayshi and Qasim al-Raymi, would resurrect Al-Qaeda in Yemen. Initially, they were largely unopposed. The US was distracted by the ongoing war in Iraq and Saleh’s government was occupied fighting the Houthis in northern Yemen. Left alone, Al-Wuhayshi and Al-Raymi rebuilt Al-Qaeda in Yemen, eventually turning it into Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and plotting and launching attacks from camps in Yemen.

During this period, 2008-2018, many of AQAP’s top figures were foreigners. Perhaps most famously, they included the American-born cleric, Anwar al-Awlaki, who was killed by a US drone strike in 2011. AQAP’s top bombmaker, Ibrahim al-Assiri, who was killed in 2017, was a Saudi, as was one of its top commanders, Said al-Shihri, who was killed in 2013. Even today, although AQAP is significantly weakened, some of its top figures are foreign nationals, including the head of the organization, Khaled Batarfi, who was born in Saudi Arabia, as well as Norweigan Anders Dale.

The Islamic State Group and the Start of a Jihadi Rivalry in Yemen

In 2015, just as AQAP was beginning to lose strength, a new Islamist terrorist organization established itself in Yemen. Taking advantage of the success of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the declaration of the caliphate, ISIS announced the formation of a branch in Yemen. Initially, this group was made up of Saudis, defectors from AQAP and new recruits. For the first few years, AQAP and the far smaller ISIS existed in a sort of “jihadi cold war,” accusing one another of various infractions, recruiting one another’s foot soldiers and sniping at each other in propaganda videos.[74]

In July 2018, AQAP and ISIS came into direct conflict for the first time, attacking one another’s camps and ambushing each other. This guerrilla war has been ongoing for the past 2 1/2 years, waxing and waning. At the moment, both groups are considerably weaker than at any point in the past five years. AQAP is riven by infighting and mistrust, while ISIS’ domestic recruiting has been hampered by its spectacularly violent tactics.

The Muslim Brotherhood

Yemen has a long history with the Muslim Brotherhood. In the late 1940s, an Algerian member of the Muslim Brotherhood, Fudhayl al-Wartalani, helped organize early resistance to the Hamid al-Din imams, which eventually culminated in the assassination of Imam Yahya in 1948 and the failed “constitutional coup.”

During the civil war of the 1960s, the popular Yemeni poet and politician Muhammad Mahmud al-Zubairi helped propagate a Muslim Brotherhood-influenced Islam within the Republican ranks. Al-Zubairi, however, was assassinated in 1965 and his “third way” – neither royalist nor Egyptian republican – largely died with him. In the 1970s and 1980s, Saleh and Saudi Arabia encouraged the spread of Sunnism in the north as a way of weakening traditional Zaidi structures.[75] Following unification in 1990, Saleh encouraged the establishment of the Islah Congregation for Reform, an Islamist/traditionalist party that is often said to be affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood. Initially, this party was led by Abdullah al-Ahmar, paramount sheikh of the Hashid tribal confederation, and also included figures such as Abd al-Majid al-Zindani, who was a member of the initial five-man presidential council in 1990. Al-Zindani was later named a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist” by the US for his ties to Al-Qaeda.[76]

For much of the 1990s, the Muslim Brotherhood operated within and took advantage of Islah’s national reach, “by mobilizing on university campuses and via the parallel institution of the Islah Charitable Society, one of only two genuinely national NGOs with branch offices in every governorate.”[77] Indeed, being part of Islah gave the Muslim Brotherhood access to Yemen through an established political party, but it also limited the group as Islah was a conglomeration of Islamists, including Salafis and tribesmen. Although Islah has gained pockets of power during the current war, most notably in Marib and Taiz, this has not directly translated into more power for the Muslim Brotherhood in Yemen.

In Yemen, the UAE, which considers the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist group, routinely equates members of Islah with member of Al-Qaeda, arguing that Islah is the Muslim Brotherhood and the Muslim Brotherhood is part of Al-Qaeda. There is no evidence to support these claims.

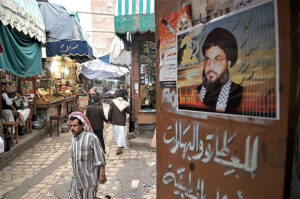

Hezbollah, a Friend and Ally of the Houthis

As happened in many countries in the Middle East and North Africa in 2006, the war between Israel and Hezbollah garnered widespread support for the latter across Yemen. However, Yemen’s relationship with Hezbollah has changed dramatically since the Houthi coup and takeover of Sana’a in 2014. Iran, as explained above, is a Houthi ally, but Hezbollah is seen as both a friend and an ally. This is partly a result of Hezbollah’s Arab identity and partly a result of its frontline status against Israel.

Hezbollah has also been a key supporter of the Houthis. Many Houthi leaders travel to Beirut more frequently than they travel to Tehran, and Al-Masirah, one of the Houthis satellite TV channels, is based in Beirut. There are believed to be more Hezbollah advisers and fighters in Yemen than there are Iranians.[78]

IV. Yemen and the Horn of Africa

Somalia, Ethiopia and the Hanish Island Dispute with Eritrea

Yemen’s relationship with Somalia is largely one of illicit trade, whether the weapons flow from Yemen into Somalia, the lesson sharing between AQAP and the Somali insurgents of Al-Shabab, or the flow of African refugees coming to Yemen as a way to enter Saudi Arabia in search of work. One of Yemen’s largest weapons dealers, Faris Mana‘a, was sanctioned by the UN in 2010 under its Somalia sanctions regime for his role in smuggling weapons into Somalia.[79] Between 2008 and 2013, AQAP and Al-Shabab had significant cross-pollination, sharing battlefield experiences and trading tactical know-how.[80] More recently, African refugees have continued to flood into Yemen, even as the war has continued, establishing camps in places like Marib in their efforts to cross into Saudi Arabia.

Like Somalia, Yemen has a long relationship with Ethiopia. Up until the 1970s, there was a significant Yemeni diaspora community in Ethiopia, many of whom were brought to the country as builders by Italy in the early 20th century.[81] Similarly, there has been a vibrant Ethiopian community in Yemen. These migration patterns and immigrant communities also led to inter-marriage, which has at times sparked discrimination and ethnic castes of people who are viewed as not fully Yemeni.[82] Descendants of mixed Yemeni-Ethiopian marriages are sometimes referred to as ‘muwaladin’, meaning the impure, or ‘habashi’, referring to the Ethiopia-Eritrea region. One of Yemen’s most famous novelists of the 20th century, Mohammad Abdul-Wali, was of mixed Yemeni-Ethiopian descent.

Yemen’s relations with Eritrea have taken a different track. In 1995, Yemen and Eritrea fought a three-day war over the Hanish Islands in the Red Sea. The Hanish Islands were coveted and claimed by both countries as they sit in one of the world’s major shipping lanes.[83] The fighting was relatively brief. A handful of troops were killed on both sides, as Eritrea captured a Yemeni military garrison and emerged victorious. But in 1998, following both French and UN involvement, an arbitration court awarded the islands to Yemen.

Eritrea has since emerged as a host for UAE bases,[84] particularly the port of Assab, where proxy units, like the Giants Brigades, received training. Eritrea, which at the time was under UN sanctions, also contributed small numbers of ground forces to the Saudi-led coalition early in the war.[85]

Oil Trade in the Bab al-Mandab Strait

In 2018, roughly 6.2 million barrels of oil per day transited through the Bab al-Mandab Strait,[86] making it one of three key choke points – along with the Suez Canal and the Straits of Hormuz – in the Middle East. In recent years, the Red Sea corridor has become a zone of regional rivalry between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and Turkey, as each country has built bases and taken over ports in the region as ways of expanding their influence.[87] Numerous states outside the region also have set up bases or a military presence along the Bab al-Mandab and Red Sea, guarding against piracy and protecting oil and trade interests. In Djibouti alone, the United States, Japan, Italy, China and France all have military bases.[88]

One of the major international concerns to emerge from the war in Yemen is that Houthi sea mines will eventually break down, become unmoored and drift into shipping lanes, creating significant insurance and actual risk.[89] Another is that the abandoned and decrepit FSO Safer oil tanker permanently moored with more than a million barrels of oil aboard will explode or leak off the northwest coast of Yemen, which could impact shipping through the Red Sea corridor and southeast to the Bab al-Mandab Strait. The Houthis, who control access to the platform, repeatedly have reached deals with the UN to allow inspectors to board the tanker only to withdraw permission at the last minute.[90]

V. Yemen and the World Powers

The United States: Yemen as a Security Problem to be Managed

The United States recognized the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen in 1946, but it wasn’t until 1959 that the US established an embassy in Yemen. Prior to that, the US ambassador to Saudi Arabia also served as non-resident ambassador to Yemen.[91] Following the 1967 war between Israel and the bordering Arab states, North Yemen cut off relations with the US. Two years later, in 1969, South Yemen also cut off its relations with the US. Relations with North Yemen were reestablished in 1972; relations with South Yemen were never reestablished.

Washington kept Yemen at a distance following the 1990-1991 Gulf War and Saleh’s ill-conceived vote in the UN Security Council. But after the USS Cole attack in 2000 and the September 11 attacks in 2001, the US-Yemen relationship shifted dramatically.

For the past two decades, the US has largely considered Yemen a security problem to be managed. The perceived threat of terrorism has impacted nearly every decision the United States has made regarding its relationship with Yemen. Initially, from 2001-2004, the US sought and received broad permission from Saleh’s government to go after Al-Qaeda in Yemen. This led to decisions such as the November 2002 drone strike, which is addressed above.

Once it looked as though Al-Qaeda had been defeated in Yemen, the Bush administration turned its attention to issues of corruption as part of its plan to democratize the Middle East. On a trip to Washington in November 2005, Saleh, who was expecting to be congratulated and feted due to his cooperation on terrorism, was told that terrorism was yesterday’s issue and today’s issue was corruption. Yemen was suspended from the Millenium Challenge Corporation, a US foreign aid agency designed to encourage good governance, as well as from World Bank programs. Saleh was livid on the flight back to Yemen.[92] Four months later, in February 2006, Al-Qaeda staged its great escape and Yemen once again was a terrorist threat.

In August 2009, AQAP nearly assassinated bin Nayef, the then-deputy minister of the interior in Saudi Arabia. Later that year, on Christmas Day 2009, AQAP managed to put a bomb and a would-be suicide bomber on a flight from Amsterdam to Detroit. Around the same time, the US was increasing its military activities in Yemen, carrying out air and drone strikes as well as shelling suspected Al-Qaeda camps from naval warships. According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in London, between 2010 and 2020 the US carried out at least 332 drone strikes in Yemen, killing an estimated 1,020-1,389 people, many of them civilians.[93]

Along with Saudi Arabia, and the UN, the US helped oversee Yemen’s presidential transition from Saleh to Hadi in 2011 and 2012.[94] The US even allowed Saleh to receive treatment, following an assassination attempt in mid-2011, at Columbia University hospital in New York.

Hadi continued the close relationship with the US, essentially granting it carte blanche to carry out drone strikes whenever and wherever the US deemed necessary in Yemen.

In February 2015, following the Houthi takeover and the group’s arrest of Hadi, the US closed its embassy and relocated all embassy personnel.[95] The US embassy staff remain outside of the country, in Riyadh.

One month later, in March 2015, Saudi Arabia announced the beginning of Operation Decisive Storm from Washington. That same evening, the Obama administration, which supported Saudi Arabia’s military intervention, announced the formation of a joint intelligence cell in Riyadh.[96] The US subsequently provided aerial refueling to Saudi and Emirati jets engaged in bombing raids in Yemen, and provided intelligence and logistical support in addition to selling the Saudi-led coalition munitions and spare parts for its air force. In 2018, during the Trump administration, the US eventually ceased aerial refueling, citing Saudi Arabia’s poor record on civilian casualties.[97]

As the Trump administration was leaving office in January 2021, outgoing Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the US was designating the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, a controversial decision that would severely impact levels of humanitarian aid entering the country. [98] Two days after the new administration took over, and just three days after the related sanctions took effect, the State Department initiated a review of the designation.[99]

The United Kingdom: A Colonial Power that Wields the Pen

The UK, as detailed above, has a long history in Yemen, from the crown colony and war in Aden to backing the royalists in the civil war in the north in the 1960s. But following the UK’s withdrawal from Aden in 1967 and the loss of its empire, it retreated from a leading role in the Middle East. In Yemen, the UK often played a supporting role to the United States, particularly after the September 11 attacks.

In January 2010, the UK helped form the “Friends of Yemen” group, which was designed to help Yemen deal with underlying causes of instability in the country. A year later, of course, Arab Spring protests erupted throughout the Middle East, including in Yemen. Although the Friends of Yemen meetings frequently produced eye-popping pledges, largely from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states, the money did not always materialize, which has been a common issue.[100]

In 2015, the UK withdrew its embassy from Sana’a shortly after the US evacuated in the wake of the Houthi takeover of the capital. At the UN, the UK has played a prominent role. Two of the three special envoys to Yemen – Jamal Benomar and Martin Griffiths – have been British citizens, and the UK is the penholder on the 2140 Committee, which drafts UN Security Council resolutions on Yemen.

Much like the US, the UK has remained a steady supplier of weapons and military equipment to Saudi Arabia. Between 2010 and 2017, the UK was the second-largest exporter of arms to Saudi Arabia.[101] Even a British court ruling that declared export licenses to Saudi Arabia “unlawful” has done little to stem the flow of British weapons to the kingdom. There was a brief pause on issuing new licenses, but in July 2020, the UK government announced that new export licenses would again be issued for Saudi Arabia. Britain’s Trade Secretary stated: “There is not a clear risk that the export of arms and military equipment to Saudi Arabia might be used in the commission of a serious violation of IHL (international humanitarian law).”[102] This conclusion is at odds with the determination of other groups such as the UN Humanitarian Council’s Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen.[103]

Russia: A Silent Actor

Like the UK, Russia – through the Soviet Union – has a long history in southern Yemen. The PDRY, as discussed above, was largely a Soviet client state during the 1970s and 1980s. Indeed, the collapse of the USSR was one of the driving factors behind the unification of north and south Yemen in 1990.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Russia played a relatively limited role in Yemen. As some scholars have pointed out, Russia lacked significant economic interest in Yemen or a military presence.[104] The Houthi takeover of Sana’a in late 2014 and the subsequent withdrawal of most western embassies in early 2015 coincided with Russia’s return to the Middle Eastern stage in Syria, where it helped prop up Bashar al-Assad’s government. In Yemen, Russia took advantage of the absence of other embassies to strengthen its ties to former president Saleh, and from 2015-2017 the Russian embassy was in close contact with Saleh. However, in the wake of Saleh’s killing at the hands of the Houthis in December 2017, Russia also withdrew its embassy from Sana’a. It has yet to return.

At the UN, Russia has made no secret of its disdain for further sanctions. The last round of successful sanctions in Yemen were passed in April 2015, prior to Russian intervention in Syria in September of that year. There have been no new UN sanctions in Yemen since that time. In February 2018, Russia vetoed a proposed UN Security Council resolution, which would have faulted Iran for violating the targeted arms embargo on Yemen by smuggling weapons to the Houthis. Instead, Russia proposed a “technical rollover,” changing the dates of the previous year’s resolution but keeping the operative language the same.

China: The Building Contractor

China’s early history in Yemen, in the 1950s and 1960s, was largely as a builder of roads. China built the Sana’a-Hudaydah road as well as a large textile factory. More recently, at the UN, China has been opposed to additional sanctions in Yemen. Much of its current concerns appear to revolve around its long term economic plan, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as China’s trade with Europe largely passes through the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea. China’s state-owned oil company Sinopec, operated in Yemen until the beginning of the war in 2015.

China’s position on the war – it supports the Hadi government – is largely a result of its desire to maintain a close relationship with Saudi Arabia.[105] Still, Beijing has managed to balance its Gulf relationships, maintaining cordial ties with Saudi Arabia, its key supplier of Middle East crude oil, as well as the other two key regional actors in Yemen, Iran and the United Arab Emirates. Those economic and commercial relationships have continued to develop since 2015 with a host of BRI-related projects, such as improving rail networks in Iran and expanding container port facilities in the UAE; in contrast, Chinese economic activity in Yemen has all but ceased.[106]

Still, China has made clear that it plans to play a role in Yemen’s reconstruction after the war ends, and that it will then resume all projects that have been suspended during the war, including an expansion of Aden’s port.[107]

VI. Yemen and Global Financial, Economic Powers

International Oil Companies

Oil was first discovered in Yemen in 1984. The initial discovery, in Marib by the US-based Hunt Oil Company, was followed two years later by another discovery in Shabwa.[108] These early discoveries and the belief that much of Yemen’s oil reserves were located in the border region between North and South Yemen helped, along with the collapse of the Soviet Union, drive the two parties toward unification in 1990.

Yemen oil production peaked at about 450,000 bpd in 2001, but despite declining since then, it has remained critical to the national economy, accounting for 63 percent of government revenues prior to the current war.[109] Following the Houthi takeover of Sana’a in 2014 and the exodus of western embassies from the capital in early 2015, foreign oil companies also evacuated the country. Total production of petroleum and related liquids that had averaged 125,000 bpd in 2014 dropped by 2016 to as low as 18,000 bpd.[110]

Yemen has been largely dependent on foreign companies such as Total, a French company that suspended its Yemen operations in 2015, for exporting its oil and gas. However, in 1997, the Yemen Gas Company (YGC) spearheaded a move to form the Yemen Liquified Natural Gas company. Total, Hunt Oil and South Korea’s SK Innovation, Hyundai and Kogas are stakeholders along with the YGC and the state’s General Authority for Social Services and Pensions in Yemen’s only LNG plant, located at Balhaf in Shabwa.[111] Yemen LNG’s first shipment set sail from Balhaf in 2009, and exports continued in the years that followed despite pipeline attacks by gunmen and saboteurs.[112] Export operations have been suspended at Balhaf since the war escalated in 2015 and the foreign firms left.

A few foreign oil companies have tried to resume work in Yemen after the initial suspensions, but currently only Austria’s OMV, which returned in 2018, is actively operating.[113] While production has increased since 2016, reaching about 61,000 bpd in 2019, that is mainly due to Yemen’s state-owned PetroMasila operations in the Masila Basin.[114]

Despite having largely withdrawn its troops from Yemen, the UAE currently maintains a force of roughly 1,000 soldiers (200 UAE soldiers and 800 local soldiers) at the LNG facility in Balhaf.[115]

The World Bank and the IMF

The World Bank has been involved in Yemen for more than four decades. After the civil war in 1994, the World Bank along with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) provided significant loans to the Yemeni government as well as to public corporations. The World Bank has, over time, pursued a shifting strategy in Yemen. Early on in the 1980s and 1990s, it sought to build durable institutions in Yemen. Then, in the mid-2000s, it began pushing decentralization to combat corruption and bloat within public and civil service structures.

The outbreak and escalation of the current war required the World Bank to quickly adapt its US$1.36 billion portfolio of conventional peacetime projects to function in a time of crisis.[116] These programs included the bank’s support to the central government’s Social Fund for Development, the social safety net the World Bank had helped the government establish in 1997, and its backing of a public works program that employed Yemenis on projects to build and improve roads, health centers, and water and sanitation facilities.[117]

Early in the war, the Public Works Project suspended its operations, but the World Bank and the United Nations Development Programme partnered in 2016 to relaunch many aspects of it nationwide.[118] By December 2019, more than 117,500 Yemenis had found work in PWP-funded projects, 30 percent of whom had been internally displaced by war. Even though the central government today is divided and dysfunctional, the SFD and PWP programs have survived.

IMF assistance to Yemen in the late 1990s and early 2000s was geared toward providing technical expertise to address the massive public-sector restructuring and reform needed after unification. Yemen also was struggling at the time under the economic consequences of Saleh’s vote at the UN against the 1991 Gulf War. In 1995, Yemen accepted IMF advice and the next year issued the country’s first five-year plan. The second five-year plan (2001-05) followed immediately after that. Building the apparatus of a modern state was intended to help Yemen diversify away from oil, and end subsidies. IMF advisers and the Finance Ministry worked together toward reforming the monetary and financial sectors. Despite efforts in areas including tax, customs, budget and banking supervision, progress was slow and programs often required several waivers to be completed.[119]

Although the IMF advice was often technically sound, it was frequently manipulated by Saleh. For instance, in July 2005, Saleh abruptly lifted fuel subsidies, which led to an immediate spike in prices and predictable riots. He then swooped in to solve the crisis he had created, which he blamed on the IMF, and began to lay the foundations for re-election in 2006. Something similar happened in August 2014, though with Saleh’s successor undercutting himself by selectively following IMF advice: Hadi cut fuel subsidies by 90 percent overnight, causing an immediate spike in fuel prices, while the IMF had been pushing for a gradual reduction in subsidies. The Houthis pressed for popular protests against lifting the subsidies in what, in retrospect, was a show of force that helped to pave the way for their takeover of the capital a month later.[120]

Prior to the war, it was Yemen’s political crisis of 2011-2012 that sank the already frail economy, prompting the IMF to approve a US$93.75 million interest-free emergency loan in April 2012. The aim was to cushion foreign exchange reserves, stimulate jobs and ease poverty to buy time for Hadi’s new government to address economic needs.[121] That time ran out, however, in 2014, when the armed Houthi movement quit a political reconciliation process in favor of war. After settling into Sana’a in September 2014, Houthi authorities began taking control of state agencies and administering the territory they had seized. Since 2016, rival branches of the Central Bank of Yemen have each tried to get the upper hand. The government-controlled CBY in Aden is able to access global financial networks, but the CBY in Sana’a under Houthi rule controls the financial center and largest markets.

The IMF still provides Yemen with technical assistance intended to “protect and preserve institutions,” particularly the central bank and Finance Ministry.[122] Yemen also was among several poorer countries to receive IMF debt service relief grants in April 2020 to help mitigate the economic impact of COVID-19.[123]

VII. Yemen and the United Nations

Following US recognition of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen in 1946, north Yemen was admitted to the UN in 1947. The UN recognized the Yemen Arab Republic on December 20, 1962, as the official government of north Yemen. This followed by one day – December 19, 1962 – US recognition of the republican government in Sana’a.

The UN subsequently established an observer mission to Yemen in 1963, which monitored the progress of the civil war in the north and the proposed disengagement of Saudi Arabia and Egypt. The mission ended in September 1964 in failure as neither Egypt nor Saudi Arabia fully implemented the disengagement agreement.

Three decades later, in 1994, the UN again approved monitors to observe another civil war.[124] According to the French delegate at the time, the Security Council wanted to preserve as much “freedom of action” as possible for the secretary-general and his special envoy so it remained “as open as possible in defining the cease-fire monitoring mechanism.”[125] On July 7, shortly after the monitors were approved, the war in Yemen ended.

The UN and the 2011 Uprising

In the summer of 2011, following the March 18 “massacre” in which more than 50 protesters were shot and killed outside a mosque in Sana’a, the UN secretary-general, Ban Ki-Moon, sent Jamal Benomar, a British citizen of Algerian descent, to Yemen as his special representative. Benomar was later named special envoy to Yemen. Throughout the spring and summer, particularly after Saleh was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt, pressure increased on the Yemeni leader to step down in the face of widespread popular protests.

Eventually, the Gulf Cooperation Council driven primarily by Saudi Arabia, the US, the UN and the EU all came together to support what came to be called the “GCC Initiative.” The deal called for Saleh to resign the presidency in exchange for blanket immunity and being allowed to remain in Yemen. Saleh indicated he would sign the deal several times only to back out at the last minute before finally signing it on November 23, 2011.[126]

As part of the arrangement, Saleh’s vice president, Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, was elected interim president in a one-man referendum in February 2012 in which “no” votes were discounted. Benomar also pushed for a broad national dialogue conference, which began in March 2013 and included participants from a variety of political parties and civil society nationwide.

A Transition that Led to a New War

The National Dialogue Conference lasted nearly a year. Soon after, the Yemeni political landscape began to shift dramatically. In the north, the Houthis managed to take de facto control over the governorate of Sa’ada defeating their local Salafi enemies at Dammaj, before advancing into neighboring Amran governorate in the summer of 2014.[127]

In Sana’a, there was a four-party standoff among former President Saleh, President Hadi, Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, and the Al-Ahmar tribal family (no relation to Ali Mohsen), which lasted until the Houthis entered Sana’a in September 2014. Hadi was originally supposed to remain president only for two years. However, in February 2014, the UN extended his term for an additional year. Before that term expired in February 2015, Hadi was placed under house arrest by the Houthis and, in January 2015, he resigned under pressure. But a month later, in February 2015, he escaped Sana’a for Aden and then Saudi Arabia, where he revoked his resignation and requested Saudi Arabia intervene militarily to remove the Houthis from Sana’a. Saudi Arabia launched Operation Decisive Storm on March 26, 2015. Hadi’s term has not since been officially extended, although he remains the “internationally recognized” president of Yemen.

The Current Peace Process

Yemen is currently on its third special envoy in the past five years. Each of these envoys has operated under the guiding principles laid out in UN Security Resolution 2216 (2015), which calls on the Houthis to unilaterally relinquish all control over government-held facilities and territory.[128] However, events on the ground have evolved and the Houthis’ control has grown to the point that it is unlikely that Resolution 2216 is a workable framework for a comprehensive settlement.

As part of the UN’s approach to Yemen, it also imposed targeted sanctions on five individuals – Ali Abdullah Saleh, his eldest son, Ahmed, and on three members of the Houthi network – established a targeted arms embargo, and created a panel of experts to monitor the sanctions regime.

UN sanctions, however, did not have the desired impact. Indeed, some have argued that although UN sanctions – an assets freeze and a travel ban – were implemented equitably across both Saleh’s network and that of the Houthis, they had a disproportionate impact on Saleh as he had international assets to freeze while the Houthis did not. Saleh’s network was eventually weakened to the point that the Houthis were able to kill him, crush his network and achieve unilateral control over the northern highlands. Multiple iterations of the UN’s panel of experts also demonstrated that the Houthis were receiving weapons and missile components from Iran.[129] But in 2018, Russia vetoed a proposed resolution condemning Iran and holding it accountable for violating the targeted arms embargo in Yemen.

In December 2018, UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths did manage to facilitate the Stockholm Agreement between President Hadi’s government and the Houthis. The agreement was, in actuality, three separate arrangements. The first, and largest, centered on the city of Hudaydah and required the Houthis to withdraw and hand over the city to local defense forces – which were never defined in the text of the agreement – and for Hadi’s government to stop a military offensive aimed at capturing the city. The offensive ended and the Houthis staged a handover ceremony that was later criticized as the Houthis handing control of the city from one internal group to another. The Houthis maintain control of Hudaydah today.

The second agreement, on the city of Taiz, produced little action. The third, on a mechanism for the exchange of prisoners, did, in 2020, produce a major exchange of prisoners. However, outside observers have criticized the UN’s role, noting that the 2018 agreement effectively incentivized the taking of civilian hostages in order to receive fighters back from the other side.[130]

Throughout 2020, much of the UN’s efforts were devoted to securing a “joint declaration,” which was to be agreed to by both the Houthis and President Hadi’s government and would include a nationwide ceasefire, economic and humanitarian steps, and the resumption of the political process. However, the year ended without an agreement.

The UN has, however, been instrumental in providing significant amounts of aid to people in need in Yemen. But in early 2020, the US cut humanitarian aid to Houthi-controlled territory due to allegations of Houthi manipulation of aid.[131] The UN was subsequently forced to shutter a number of programs in the north. Yemen is often referred to as the “world’s worst humanitarian crisis” by the UN; several outside observers believe the situation will be made worse by the US’ designation of the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization.[132]

In Yemen, the UN also oversees the UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM). The program, which is based on Security Council Resolution 2216, began work in May 2016 and is based in Djibouti, where ships are required to dock to ensure they are in compliance with UN sanctions before proceeding to Yemen. However, Saudi Arabia had little trust in UNVIM, which led to dual inspections — one in Djibouti and another in Saudi — before ships were allowed to dock and unload in Yemen. This delay increased shipping costs and insurance rates and, at times, led some perishable goods to expire. In 2017 and 2018, the UN’s panel of experts was tasked with finding ways to strengthen Saudi trust in UNVIM.[133] The panel was unsuccessful.

VIII. Conclusions

Yemen is currently beset by three separate yet overlapping wars.[134] There is the US-led war against terrorism, the Saudi-led regional war against what it sees as an Iranian proxy, and the domestic civil war. Two of these three wars are foreign-led. But it is the third war, the domestic civil war, that will likely prove to be the most intractable.

The US-led war against terrorism waxes and wanes in Yemen, and is currently in a dormant phase. The Saudi-led regional war, the war that gets most of the media attention and has done much of the destruction, is, counter-intuitively, the easiest to solve. Although any peace agreement, settlement, or withdrawal is unlikely to happen under the framework of UN Security Council Resolution 2216. Facts on the ground have long since surpassed the 2015 resolution, which effectively calls for a unilateral Houthi surrender. What is much more likely is a negotiated, face-saving Saudi withdrawal from Yemen, ending this portion of the war. The Biden administration has made clear that it intends to end US support of the war and Saudi Arabia, with the incoming Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, saying the new administration would “review the entirety of the relationship” with Riyadh.[135] He did not indicate whether Washington would seek an active role in resolving at least the regional element of the war in Yemen, although it is widely assumed this is what the new administration will do.