The Sana’a Center Editorial

Biden Needs a Yemen Policy That Doesn’t Look Back

Each successive United States president over the past two decades has escalated America’s military involvement in Yemen in pursuit of ends in which Yemen itself was, at most, a secondary concern. In doing so, the US, and in particular the office of the president, has helped foster the situation Yemen faces today — splintered as a nation and facing one of the largest humanitarian catastrophes of the modern era. In helping to facilitate Yemen’s dissolution, Washington has also undermined the same interests it sought to pursue in the country – counterterrorism and its relationship with Riyadh. There is thus a moral and strategic imperative for the incoming US administration to meaningfully reorder priorities to change course.

President George W. Bush authorized the first drone strike in Marib governorate in 2002 and through the 2000s his administration became the driving force behind the creation of Yemeni special forces units to fight in his so-called ‘War on Terror’. Much of this US-supplied weaponry and training, however, was redirected by the government in Sana’a in an attempt to brutally quash a rebellion at the time in the country’s north by a nascent Houthi movement. Later, these same special forces were deployed in a bloody attempt to try and put down the mass popular protests of Yemen’s 2011 Arab Spring uprising.

Following Bush, President Barack Obama dramatically increased the use of drone strikes in Yemen against suspected Al-Qaeda operatives, without any accountability or transparency regarding the increasing number of civilians also killed. In 2015, his administration backed the Saudi- and Emirati-led military coalition intervention in Yemen against the same Houthi movement. Among other things, Obama’s tenure entailed American-trained pilots dropping American-made bombs across much of Yemen while US diplomats at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) helped secure international legal cover for the coalition and blocked attempts to hold it accountable for war crimes. President Donald Trump, once in office, doubled down on these Obama-era policies, scaling up drone strikes and special forces operations in Yemen, signing billions of dollars worth of weapons contracts with the coalition while also shielding Riyadh from accountability for its actions in its southern neighbor.

The outsized impact the US has had in Yemen through three successive administrations has come in the absence of any coherent foreign policy regarding the country itself. Rather, for American presidents (and the Washington establishment generally) Yemen has not been a policymaking consideration beyond its function in pursuing two cardinal US interests: counterterrorism and preserving the US relationship with Saudi Arabia. While both will remain key White House priorities, Joe Biden taking office in January 2021 could lead to a new US approach in which deescalation of the Yemen war, and the establishment of a sustainable peace thereafter, also feature on his agenda. It seems just as plausible, however, that the former vice president will stack his offices with Obama-era staffers who will repackage the priorities and policy approaches of the last Democratic administration in the guise of a ‘fresh start’.

Biden’s campaign pledge to withdraw US support for the Saudi war effort will be insufficient to bring about peace in Yemen unless it is accompanied by a diplomatic surge. Saudi Arabia is lost for options it can stomach and needs diplomatic support to exit the quagmire it created for itself. Meanwhile, Iranian leaders, the Houthi movement’s main international backers, will take a breath once the capricious Trump is out of the White House and evaluate whether they are willing to make compromises in the region for the sake of renegotiating the nuclear deal that Trump scuttled, and attain a degree of sanctions relief for its battered economy. The US is still the best-placed actor to lead an international effort to leverage the conflict’s relevant players back to the negotiating table, even after Trump’s four-year assault on multilateralism.

UNSC resolution 2216 – which forms the legal basis for the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen – was passed in April 2015 and comes up for its annual renewal in February 2021. Negotiating an update to this document at the Security Council would be an ideal place for a Biden administration to start. These negotiations should also include expanding the criteria and scope of the Yemen Sanctions Committee’s work.

The need for the new US president to prioritize peace in Yemen should be clear. Absent a sustainable peace deal in Yemen, the most likely outcome is continued dissolution in the south and, in the north, a Houthi-run statelet along the Saudi border with access to the Red Sea – both of which would pose long-term threats not only to Saudi Arabia, but also to Washington’s economic interests and regional security priorities.

Contents

- November at a Glance

- State of the War

-

Features

- Journey into Shabwa – by Ryan Bailey

- Three Weeks in a Houthi Prison – by Casey Coombs

-

Expert Roundtable Discussions

- Biden Takes Over: Advice and Expectations for a New US Administration – by Stacey Philbrick Yadav, Baraa Shiban, Gregory D. Johnsen, and Thomas Juneau

- Trump’s Endgame: Weighing a Houthi FTO Designation – by Waleed Alhariri, Maysaa Shuja al-Deen, Abdulghani Al-Iryani, and Maged al-Madhaji

- The Conversation

-

Arts & Culture

- The Handsome Jew: An Excerpt – by Ali al-Muqri, translation by Mbarek Sryfi

- The American Way of War: A Review of Phil Klay’s Missionaries – by Brian O’Neill

November at a Glance

Political & Diplomatic Developments

Houthis Appoint Ambassador to Syria

On November 15, the Houthi authorities announced they were appointing Abdullah Ali Sabri as the Houthi ambassador to Bashar al-Assad’s Syria. This is the second ambassador the Houthis have appointed, following the appointment of Ibrahim al-Delaimi as ambassador to Iran in August 2019. In October 2020, Iran reciprocated, naming an ambassador to Houthi-controlled Sana’a.

Houthis Slated to Release Hadi’s Brother in Coming Prisoner Exchange

Senior Houthi official Mohammed al-Houthi confirmed on Twitter that President Hadi’s brother, Nasser Mansour Hadi, would be among the prisoners released in the next planned swap with the Yemeni government and Saudi-led coalition. Nasser Hadi is one of the four prisoners whose release is demanded by UN Security Council resolution 2216. According to Abd al-Qadir al-Murtada, the head of the Houthi prisoner negotiation department, the next prisoner exchange will be 101 government prisoners for 200 Houthis.

October saw the largest official prisoner exchange between the warring parties since the conflict began. The product of UN-sponsored negotiations in Switzerland the previous month, 1,081 prisoners were released over the course of two days, in an exchange facilitated by the International Committee of the Red Cross. (For analysis, see ‘Yemen’s Prisoner Exchange Must be Depoliticized’.)

Economic Developments

Yemen’s CBYs Battle Over Financial Data

Houthi forces raided the headquarters of the Tadhamon International Islamic Bank in Sana’a in mid-November, shutting off cameras and ordering workers to leave. The Houthis kept control of the bank for several days, forcing its 37 branches across Yemen to close. The incident was sparked by Tadhamon’s sharing of financial data with the Hadi-controlled Central Bank of Yemen (CBY), and came as just one salvo in a wider battle between the rival central banks in Aden and Sana’a to control access to the country’s financial sector data in recent months (for details, see Yemen Economic Bulletin: Battle to Regulate Banks Threatens to Rupture the Financial Sector). Tadhamon was allowed to reopen after paying a fine.

The struggle between the two CBY branches eased slightly by the end of November. According to banking officials in Sana’a, the de-escalation came after the central banks agreed to the creation of a high-level banking mediation committee composed of the chairmen of four Yemeni banks: International Bank of Yemen, Yemen Kuwait Bank, Tadhamon International Islamic Bank, and the Al-Kuraimi Islamic Microfinance Bank.

Widening Disparity between Yemeni Riyal in Sana’a and Aden

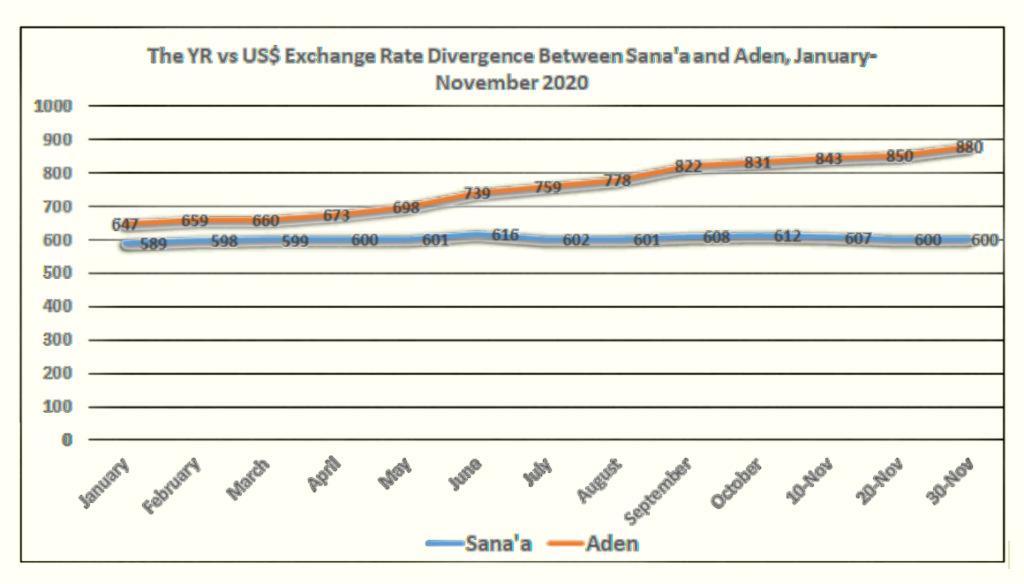

Newly-printed Yemeni rials, which are used in the south but banned in Houthi-controlled territory, lost significant value in November, further widening the divergence between the exchange rates. At the beginning of December the Yemeni rial was trading at 880 to 1 against the US dollar in Aden, and at 600 to 1 against the dollar in Sana’a.

Putting further downward pressure on the value of new rials, in November the CBY-Aden received a batch of new rial banknotes printed abroad, amounting to YR180 billion in physical cash. The Yemeni government has been printing money in part to address its large fiscal budget deficit. Of the YR180 billion delivered in November, close to YR100 billion was used to pay nearly two months of late wages to military and security units.

Houthi Authorities in Sana’a Suspend Salary Payments

On November 19, the president of the Houthi-aligned Supreme Political Council, Mahdi al-Mashat, announced the suspension of salary payments to public servants working in Houthi-controlled areas. In January, Al-Mashat had directed the Sana’a-based Ministry of Finance to pay half a salary every two months to all civil and military employees operating under the Houthi-controlled government. That pledge was not met. Since 2016, most of Yemen’s 1.25 million public sector employees have not received regular salaries.

(For details on these and other economic developments, see ‘Yemen Economic Bulletin: November Updates’.)

Humanitarian & Human Rights Developments

Malnutrition and Food Insecurity Growing in Yemen

The latest analysis by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), UNICEF and the World Food Programme found more than half a million children under 5 suffer from acute malnutrition across 133 districts assessed in government-controlled Yemen — a nearly 10 percent rise in cases in 2020. The rise comes as Yemen’s Humanitarian Response Plan for 2020 is only 48 percent funded, meaning 4 million fewer Yemenis are receiving aid each month than were at the start of the year.

A separate Integrate Food Security Phase Classification report projected that the number of Yemenis facing acute food insecurity would rise from 13.5 million to 16.2 million by June 2021, and in that time those facing an emergency food security situation would rise from 3.6 million to 5 million people.

Environmental Developments

Houthis Agree to Allow FSO Safer Oil Terminal Inspection

On November 24, the UN announced that the Houthis had given permission for a team of technical experts to visit and assess the FSO Safer oil terminal off the coast of Hudaydah. The visit is scheduled to take place in January or February. The Houthis had agreed to a similar visit in July, but no visit materialized (for details, see ‘Refocused Attention on Potential FSO Safer Oil Terminal Disaster’). The decrepit vessel holds more than 1 million barrels of oil onboard and is a potentially catastrophic environmental risk for the Red Sea and surrounding coastal areas (for background, see ‘An Environmental Apocalypse Looming on the Red Sea’.)

Shibam at Risk of Collapse

Parts of Shibam, an UNESCO world heritage site, are at risk of collapse from heavy rains and flooding that have struck Hadramawt over the past several months. The mud-brick city, often referred to as the “Manhattan of the Desert,” has suffered from a lack of funding for restoration efforts, which have been further hampered by the ongoing war and a lack of skilled laborers.

Locusts Continue to Plague Yemen

The FAO said locusts were continuing to decimate crops in Yemen, including date palms. In a statement, the FAO said that Yemen’s climate and geography represent a fertile breeding ground for the locusts, and that controlling their spread was critical to containing new outbreaks. However, the FAO has been unable to access many parts of the country due to the ongoing fighting.

International Developments

US Debates Designating the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization

The Trump administration is reportedly debating whether to designate the Houthi movement as a Foreign Terrorist Organization. Such a move would criminalize most interactions with the group conducted without US government waivers. In anticipation of the designation, the UN and other aid organizations have withdrawn American employees working in Houthi-controlled territories. (For more on the potential US designation of the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, see ‘Trump’s Endgame: Weighing a Houthi FTO Designation‘.)

US Weapons Sale to UAE

The Senate is set to vote the week of December 7 on a proposed US$23 billion weapons sale to the UAE, which would include F-35 fighter planes, MQ-9B drones, as well as munitions and missiles. The proposed deal has been criticized by Democratic lawmakers, who accuse the Trump administration of attempting to rush through the sale without a proper review process before the president is set to leave office in January 2021.

State of the War

By Abubakr al-Shamahi

Marib

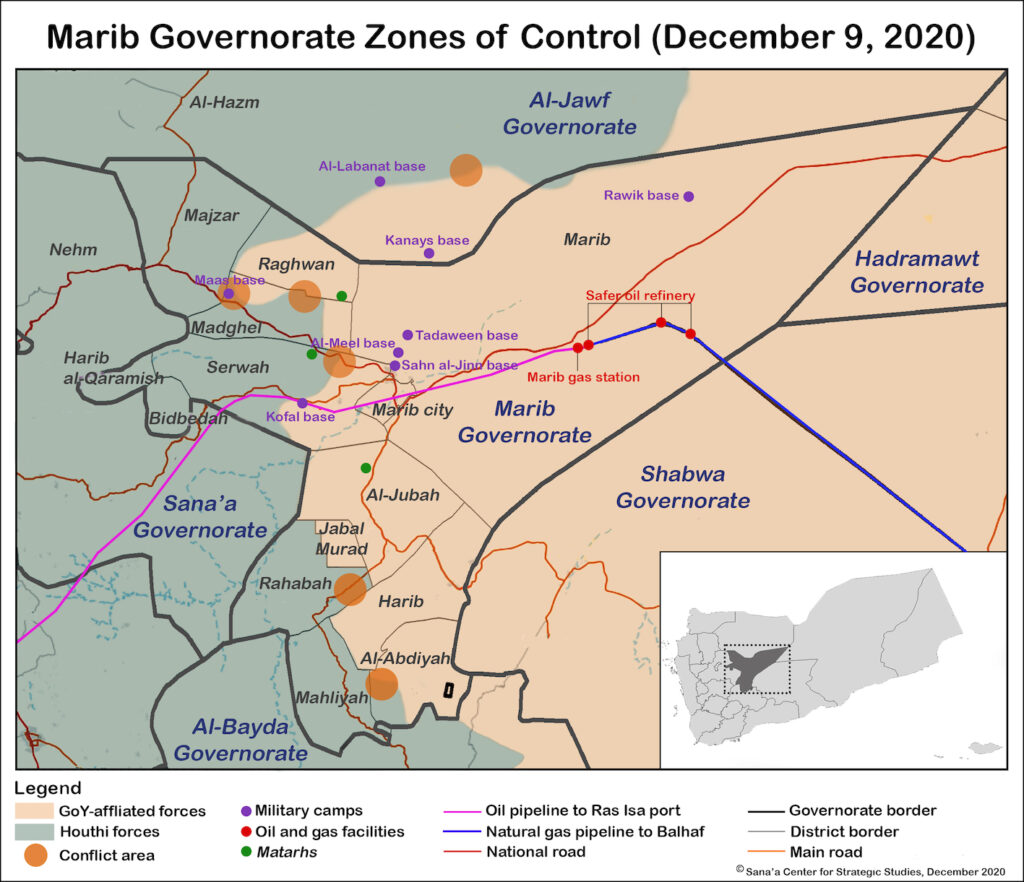

The story of the battle for Marib in November centered on the fighting over the strategic Maas base, the temporary headquarters of the Yemeni government’s 7th Military District. Lying in the northwestern district of Medghal, west of Marib city, Maas slowly slipped out of the hands of government forces as the month progressed. Houthi forces had been edging toward Maas for a number of months, and by the start of November were positioned only a few kilometers from the base, attacking it from the south, north and west.

An early indication that Yemeni government forces saw the battle for Maas as a lost cause came on November 5, when they removed heavy weapons from the base. Earlier, Houthi forces had captured a section of the main road between Maas and Marib city, forcing the Yemeni government to use a longer route to resupply its forces at the base. However, even the alternative supply line route through Raghwan district was attacked by Houthis forces, which had taken control of Yemeni government positions in western Raghwan by mid-November. The fighting in Raghwan impacted several villages, displacing local residents.

Despite Yemeni government attempts to delay the Houthi advance by mining the areas surrounding Maas base, government forces were eventually forced to withdraw from the base on November 20. Houthi forces have moved in to occupy the base, but government shelling and coalition airstrikes have at times forced them to leave. Ongoing fighting in the vicinity of Maas base has resulted in dozens of casualties on both sides, including senior Yemeni government military commanders and members of the Jada’an tribe, which has fought alongside the Yemeni government. Naji bin Naji Ayidh, a commander in the 7th Military District, was among those killed.

Taiz

Fighting between Yemeni government and Houthi forces in Taiz city has recently centered on Al-Arba’een street frontline. With frontlines in the city largely static for more than two years, even minor advances are considered a success. Yemeni government forces captured a number of positions and buildings occupied by Houthi fighters in Al-Arba’een, in the northern part of the city, throughout November, including Al-Na’man school and Al-Hanjar building. About a dozen casualties were reported on both sides during the fight for these positions. Houthi forces also launched mortar attacks from their positions in Al-Arba’een toward populated areas of Taiz city, leading to civilian casualties, according to local residents.

Fighting also took place throughout the wider governorate, with some of the fiercest clashes seen in the western Maqbanah district in early November. On November 7 and 8, fighting for Al-Barkanah military position in eastern Maqbanah saw multiple Yemeni government and Houthi casualties, but ultimately government forces continued to hold the position, despite a brief period of Houthi control. On November 11, Yemeni government forces attacked and captured Houthi positions in the areas of Tabbat al-Khazzan and Tabbat Hamid, southeast Maqbanah, after battles that resulted in multiple casualties on both sides, according to local sources.

Also in Taiz, a number of Yemeni government soldiers were killed in a November 5 drone attack on a training camp in Jabal Habashi. The military camp was set up with the support of Islah-affiliated commander Hamoud al-Mikhlafi, a leader in the local Taiz resistance to the Houthis at the start of the war who is now based in Turkey. The perpetrator of the drone attack on the camp is unknown. The drone attack came on the same day that Khaled Fahdel, the overall commander of the pro-Islah Taiz Military Axis, ordered the removal of several military commanders believed to be close to Al-Mikhlafi.

Abyan

Despite regular media reports of an imminent deal to implement the Riyadh Agreement between the Yemeni government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC), November clashes between the two sides on the Shaqrah frontline in Abyan proved among the deadliest since August 2019. The first major escalation in fighting came on November 9, when those killed included a Yemeni government Special Forces field commander, Abdulnasser Ahmed al-Mashraqi. On November 13, the brother of Brigadier General Loai al-Zamiki, Commander Haitham al-Zamiki, was killed in fighting.

On November 20, Yemeni government forces took control of Musa farm near the village of Sheikh Salem, part of a rare military advance in Abyan that followed clashes in Al-Taryah area, east of Zinjibar city, and at Al-Kathib mountain, northeast of Zinjibar. Casualties were reported on both sides, and 20 STC fighters were taken prisoner by the Yemeni government, according to military sources. A mediation team from the Saudi-led coalition present in Abyan has continued its attempts to halt the fighting, but its lack of success in November indicates the distance between the Yemeni government and the STC when it comes to agreeing to a new cease-fire and power-sharing deal.

Hudaydah

Fighting in Al-Durayhimi city, south of Hudaydah city, ground to a standstill by the end of November. Houthi forces continued their efforts to break through the lines of the coalition-backed Joint Forces in the north, south and west of the city, without much success, while the Joint Forces, led by Tareq Saleh, have been unable to re-encircle Houthi forces in the city.

Clashes in and around Hudaydah city also continued throughout the month, with the fighting displacing 56 families from Mandhar neighborhood in southern Hudaydah city.

Abubakr al-Shamahi is the research liaison at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. As a journalist his work has appeared in outlets such as Al-Jazeera English, The Guardian, TRT World, the New Arab, and the BBC. He tweets at @abubakrabdullah.

Features

Journey into Shabwa

By Ryan Bailey

In November, the Sana’a Center organized a visit by an international press delegation to Yemen’s Shabwa governorate. This was the third such trip the center has arranged, with previous ones being to Marib and Hadramawt, and came as part of the Sana’a Center’s continuing commitment to ensure the world, through its media, has a window onto Yemen – given the international press’ restricted access to the country due to the ongoing war and pandemic. Ryan Bailey, an editor and researcher with the Sana’a Center based outside the country, traveled to Shabwa with the delegation and documented their tour around the governorate and those they met during his first trip to Yemen.

Day 1 – Arrival

It is early evening when our Yemenia Airways flight touches down at Sayoun airport. I walk down the stairs into the warm desert air in a long line of Yemeni families, our delegation of international journalists, and a smaller group of international students on their way to study at Dar al-Mustafa, a renowned Sufi Islamic center in the nearby town of Tarim.

This moment nearly didn’t happen. Earlier in the day our tickets had been canceled only a few hours before our scheduled takeoff at Cairo airport, leaving us scrambling. We at the Sana’a Center had been planning this trip for months, lining up permissions, checking boxes, and taking COVID-19 tests, but apparently someone in the Yemeni government or the Arab coalition that controls Yemen’s skies had second thoughts about allowing a bunch of western journalists into the country. As the clock ticked down on our departure time the Sana’a Center’s chairman Farea and executive director Maged worked the phones, cajoling, threatening, schmoozing, asking for favors and calling in owed ones, until finally we managed to delay the flight for an hour – enough time to secure renewed permission, board the plane, buckle in and take off.

After customs and a baggage inspection at Sayoun, we are led into a sideroom: it’s time to eat. On a plastic sheet covering the floor sits large round plates piled with rice beneath roasted lamb, served alongside delicious malawach (Yemeni flatbread) and sahawiq (an incredible version of Yemeni salsa). Later, satiated from the delectable meal and still a bit disoriented from the flight, our group of 16 piles into four armored SUVs, for the six-hour drive through the darkness to Ataq. Our trip will take us through Hadramawt and what I’m told is stunningly bleak and beautiful terrain to the capital of Shabwa’s governorate. The SUVs arrange themselves into a convoy and our escorts – Yemeni national troops, local Shabwani security forces and armed tribal men in technical vehicles – fall in around us. I’m too wired to sleep, and spend much of the drive gazing out the windshield at the guard vehicle in front of us, wondering about and feeling sympathy for the armed men crammed together in the back of the pick up truck ahead of our vehicle.

Al-Qaeda elements are still present in the Wadi Hadramawt area around Sayoun, so we want to get through the area quickly. The bulletproof windows in the armored cars don’t roll down, and there’s not much to see behind the tint out into the night, save for rudimentary checkpoints.

Several members of our group chew qat to pass the time. I’m given a tutorial by Ammar, one of the main organizers of the trip, who hails from a prominent Shabwani family, on how to best prune the shrub before sticking stem and leaves into my mouth, and chewing to form a ball in my cheek. The qat is bitter at first, but I soon get used to, and even begin to enjoy, the taste of the mild narcotic. Our car even samples several varieties, with the juiciest qat being from Yemen’s northern governorate of Sa’ada, the home of the Houthi movement.

I can tell we’ve reached Shabwa by the change in the road. In Hadramawt the highway was cracked and pot-holed, at times giving way to dirt or berms of sand. Shabwa’s is smooth asphalt. We’re ascending slightly as we near Ataq. I can’t really feel it, but the popping in my ears tells me we’re climbing toward the city more than 1,100 meters above sea level.

Finally, we see the lights of Ataq’s main boulevard in the distance. That’s one of the first things you notice in Yemen: the lack of lights. We’ve been driving for hours and these are some of the first lights we’ve seen.

The road into town is lined with pictures of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, which appear new and posted for the convoy to see, and Governor Mohammed Saleh bin Adio. This is Ataq, our home for the next week.

Day 2 – The Governor

We wake early at Al-Fakhamah hotel, pile into cars, and weave through Ataq’s morning traffic to the heavily guarded governor’s residence. Pulling into the compound, I see a number of tiny toy-like gazelles grazing on the lawn. A gift to the governor from one of Shabwa’s tribes, I later learn.

We are greeted at the entrance by the governor himself and a number of other local dignitaries. Bin Adio speaks slowly and deliberately, necessitating the audience to listen carefully to his words. Like any good politician, he stresses the local authority’s accomplishments and focus on development, particularly in terms of roads, electricity and healthcare. The governor is rightly proud of what his team has accomplished in the midst of a war, and mentions that the new hospital in town has been constructed with the 20 percent share of Shabwa’s oil and gas revenue that the local authority negotiated with the central government. Because the soon-to-be-opened hospital was built with local funds it will sit under local authority, not under the national Ministry of Health. Most of this building boom, however, has been orchestrated from the top, with contracts for buildings and road paving awarded without a competitive tender process.

Lunch in a large basement room of the governor’s residence is another feast. Lamb, rice, fresh fruit, vegetables and a local dish, baby shark.

After eating, it’s time for a qat chew in the governor’s diwan. Sitting on long couches, which ring three sides of the room, the governor and his team take turns explaining the ongoing struggle between the Yemeni government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC), which is backed by the United Arab Emirates. Last August, the two came to blows, with the STC taking control of Aden and heading east. But the STC offensive was broken in Ataq, where local tribes and government forces combined to defeat the UAE-backed Shabwani Elite forces and end the separatists’ bid to extend their control across southern Yemen.

Since the STC’s defeat last year, Shabwa has been under almost complete government control. The only exceptions are two bases that still house Emirati forces: Al-Alam camp north of Ataq, and the Balhaf liquid natural gas terminal, the largest investment project in Yemen’s history. At the latter, the UAE maintains a mixed presence of 1,000 troops, about 200 Emirati soldiers and 800 Shabwani Elite troops. Bin Adio’s dislike for the Emiratis is obvious.

Day 3 – COVID-19

Today we try to tackle one of the most pressing questions of our trip: what exactly happened to COVID-19 in Yemen? Is the country through it, in a trough, about to get hit again?

Our first visit of the day is to Ataq general hospital. Here, doctors and hospital staff dutifully relay a litany of challenges facing the health sector: a critical shortage of staffing, supplies and equipment as the hospital strives to treat a growing number of cases of severe pediatric malnutrition, cholera, diphtheria and dengue fever.

Given these other maladies, COVID-19 isn’t at the top of staff’s worries. The doctors we speak to say there was an initial spike in cases earlier in the year, but that the virus appears to have receded and nearly disappeared in recent months.

After the hospital, we visit the brand new COVID-19 quarantine and testing center. Here we are told that the facility is one of the best equipped in the country but has not recorded a confirmed case of COVID-19 since August. How is this possible, particularly given the scant attention paid to precautions such as mask-wearing and social distancing in Shabwa?

There are a lot of theories, but no real answers. Some speculate that COVID-19 can’t survive in a warm climate, or maybe Yemen’s relatively young population may have helped it escape the worst. Others argue for strong Yemeni immune systems or good local morale. My favorite explanation for why coronavirus has not taken hold in the war-ravaged country came from Governor Ben Adio: “God has never given two misfortunes.”

We cap off our day watching the sunset from a plateau outside Ataq. Various plateaus line the desert from Shabwa to Hadramawt, and the winding trip to the top on the narrow, single-lane road proves more than worth the occasional hair-raising moment. The sublime red Arabian sunset provides an opportune moment for quiet contemplation.

(Editor’s note: On December 6, Shabwa recorded its first confirmed case of COVID-19 in months.)

Day 4 – The Coast

Today is Friday, the start of the Yemeni weekend, so we head south to the coast. Our destination is the Balhaf LNG terminal. The site has not been operational since the start of the conflict and is a major source of the tensions between bin Adio and the UAE. The governor, who says “the UAE did not give us a single bullet to fight the Houthis,” wants the Emirati forces out, foreign oil companies back, and operations restarted. But the Emiratis don’t look like they’re going anywhere.

In addition, questions remain over the appetite for international oil companies to return to Yemen at the current time, even with the relative security in Shabwa. Austrian OMV, which operates an oil field in Shabwa’s Habban district, became the first international oil company to resume operations in the country in 2018, but thus far none of the partners in the Balhaf project, most notably French Total, have indicated they would be ready to restart operations.

Traveling down south we hurtle toward the Arabian Sea. At one point, we reach an intersection that branches west toward Aden and east toward Mukalla. This was the farthest point Houthi forces reached in Shabwa in 2015, before being turned back by the Saudi- and Emirati-led military coalition and finally expelled from the governorate in 2018. We turn east, driving through Azzan, which Al-Qaeda militants held in 2011 and 2012, and again for a brief period in 2016. So many different wars over the same terrain.

Green starts to appear as we near the coast, small river beds feeding shockingly lush patches of vegetation. Our convoy passes several groups of African migrants, who pay smugglers to bring them to Yemen’s coast in hopes of crossing the country and making it to Saudi Arabia. On the coast everything appears sharply defined and clear. To the left are dunes of sand, an occasional camel wandering into sight. To the right, the Arabian Sea. Creeping toward Balhaf, black volcanic rock also makes an appearance in the distinctive landscape.

Our initial plan to enter the Balhaf facility falls through. The UAE and governor’s office would later exchange blame for the lack of coordination related to our visit.

Instead we head to a pristine stretch of beach at Bir Ali, an ancient seaport that aspiring locals dream of turning into a resort. There we hear about plans for the seaside development, which the project manager hopes will eventually cater to both Yemeni tourists and foreign visitors. A few of us can’t resist jumping in the sea for a quick swim, and waist-deep in the emerald blue water, that almost seems possible.

Day 5 – The Desert

Just before sunset we leave Ataq and head to the desert for a meeting of tribal sheikhs. Over cups of sweet tea, we listen as they explain Shabwa’s tribal history and customs, and the integral role tribes play in a society with a weak central state. This isn’t just history. It was the tribes that turned the tide on the STC advance in August 2019 – with tribes on both sides they refused to fight among themselves and forced the STC to retreat back toward Aden.

Dinner is more succulent lamb. While eating we learn that in some tribes custom dictates the host be given a certain part of the lamb, who then gives it to the person who cooked the meal. Known as assaybah (literally translated as ‘doing the right thing’), the challenge is that this reserved cut of meat can differ from tribe to tribe, and region to region. The guest better figure it out, however, because failing to honor this tradition would be considered quite the faux pas in tribal society. While foreigners may get a pass, a Yemeni would never be exempt from understanding and honoring such unspoken, and sometimes contradictory, rules. For dessert, there is Masoobah, spongy soft bread in a bowl smeared with honey. This part of the meal especially necessitates that we experience washing our hands the tribal way. Rubbing them in the sand, we make our way over to a tanker truck and rinse them with water coming out of a spout at the back into a bathtub basin.

After exchanging farewells with our gracious hosts, we scatter to our various vehicles and under the starry sky our convoy flies over the sand back to Ataq.

Day 6 – The Souk

Sunday morning starts with a visit to the Ataq souk. The road there takes us past a large shantytown, home to muhamasheen, literally “the marginalized ones,” and the bottom of Yemen’s traditional social pyramid. Reaching Ataq’s old city, we pass several buildings dating to South Yemen’s socialist era. If you look closely, there is still an outline of a red star on some facades.

At the souk, honey is the main item on offer. The local variety, derived from the nectar of sidr trees, is considered among the best in the world, and Shabwanis are rightly proud of it. Locals will tell you Shabwani honey is the best in Yemen, and laugh off challenges from others claiming Wessab or some other location to be the paramount producer in the land. A few samples in, local sellers explain that roughly half of Shabwa’s honey is exported abroad, helping producers pocket on average between US$40,000 and $70,000 during the three-to-four month harvesting season.

Day 7 – Bees

The next morning, we set off to see honey farmers in action. We pull into a stretch of land, off Ataq’s main road, and find several men crouched over a line of drawers, each filled with a beehive. Bees swarm around the heads of the workers, who set alight tiny pieces of burlap that give off smoke to pacify the bees as they pull honey.

The owner of the apiary, who says he got into the bee business after using his savings to purchase several hives a few years ago, kindly explains how he transports them, bringing his bees to wherever the best sidr trees are blossoming at the time. Beekeepers coordinate over WhatsApp, sharing tips and comparing notes on the proper geographical distribution of bees to produce the best yield.

Back at the car, Salem, our driver and Governor Bin Adio’s personal secretary, says he recognizes the bee farmer. He was detained a while back, and “held for six months as an Al-Qaeda sympathizer.” The information is both jarring and comically absurd, and we share a laugh in thanks over his career change.

Day 8 – Road trip

Leaving Yemen is complicated by our initial ticket cancellation a week earlier, so after some debate it is decided that we should drive out via the country’s eastern border with Oman, 20 hours away. Our entire group registers negative PCR tests – hamdallah – so we and our armored convoy leave Ataq around 6 a.m. After having chewed all through the night before, I sleep for much of the journey, eventually waking as we begin a stark and winding ascent from Wadi Hadramawt on a road flanked by two canyons. With several hours left before the border, again I start to dose, with images of the desert dancing in my mind.

Ryan Bailey is an editor and researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

Three Weeks in a Houthi Prison

By Casey Coombs

On May 15, 2015, I sat between two Yemeni officers in a police truck behind the Criminal Investigation Department in Sana’a. “You’ll be free in two hours,” one of the officers told me as he stared anxiously at the building, which housed a prison run by the US-backed Counter-Terror Unit (CTU).

Earlier that day, a group of teens clutching AK-47s covered in Houthi stickers entered my home in Sana’a’s Al-Buniyah neighborhood, searched my belongings and handed me off to cops from a nearby police station. The station chief and a man in army fatigues wanted to know every detail about my time in Yemen and why I hadn’t left the country when the war started a few months earlier.

I explained that I was a journalist who had been based in the capital for three-and-a-half years, and I had tried to leave several times in recent weeks. The day before, an intelligence official at Sana’a International Airport had turned me away at the boarding gate to a UN-organized evacuation flight because my passport didn’t have the proper stamp, and the customs agent who could resolve the matter had already gone home for the day.

“Come back tomorrow,” he said.

Fighter jets had been bombing Sana’a daily for about six weeks as part of Operation Decisive Storm, a Saudi-led military campaign aimed at reversing the coup that swept the armed Houthi movement and former President Ali Abdullah Saleh to power in late 2014. In the ensuing frenzy to consolidate control of Sana’a, Houthi and Saleh forces appeared to be rounding up anyone viewed as a potential threat to their rule, or who could be used as a bargaining chip in the struggle. In my case it was a disgruntled landlord who delivered me to the de facto authorities. I’d been short $100 in rent for the remainder of May and was told to pack up my things and move out. When the landlord’s normally mild-mannered guard tried to push his way through my front door, I pushed back. He regained his balance, raised his arms as if he were holding an invisible rifle pointed at my face and said he was going to get the Houthis.

Once I was in the hands of the authorities, they kept passing me up the chain of command until I was in a maximum security prison outside the capital. The $100 in late rent never came up during interrogations.

****

After about 45 minutes in the parking lot behind the Criminal Investigation Department, a man with white hair and a commanding presence emerged from the building. A shiny white van with tinted windows pulled up to the man, and he ordered the policeman to bring me out. I had seen these types of vans at Houthi compounds throughout the city in recent months. Hoping that the mix up would be over in a few hours, I tried to ignore the van and what it meant: I was in Houthi custody and things were about to get worse.

“Hello, Casey,” the white-haired man said calmly in English as I approached, assuring me there was nothing to worry about. With a hint of regret in his voice, he told me I was going to be handcuffed. A soldier grabbed a traditional Yemeni shawl from the white van, twisted it into a long cord and tethered it around my wrists. I didn’t resist.

They opened the sliding door of the van and ushered me inside.

“We have to put this on your eyes,” the white-haired man said from the front passenger seat, as the soldier draped another shawl over my face and tied a knot at the crown of my head. “Okay? Too tight?” the white-haired man asked in a stern but sympathetic voice. “It’s okay,” I said, surprised by his accommodating manner.

When I tried to ask where we were going, he cut me off.

“You’ve done something terrible! You’re a liar! Shut up and put your head down!” he shouted, reaching back to shove my blindfolded head down between my knees.

With my head pinned against the back of the driver’s seat near the floor, the van spun out of the dirt lot onto a busy street. I could feel the backs of my knees sinking into the bench seat as the van accelerated. The sound of the engine blended with honking horns and a muffled Arabic conversation in the front seat. The driver had a jarring stop-and-go style. He slammed the brakes, skidding around a corner and jamming my left leg into a sharp piece of metal. Just as quickly, he was accelerating again, weaving through the unseen traffic. On my right, the soldier tightened the makeshift handcuffs, cutting into the circulation in my hands.

At some point, I’m guessing about 30 minutes later, we pulled into a secretive National Security Bureau (NSB) base in the northeastern part of Sana’a, where intelligence officers trained alongside paramilitary forces from the CTU. A prison on the base was used to detain and interrogate “terrorist elements,” former NSB director, Ali al-Ahmadi, told me recently. He said the US had helped build two newer CTU facilities on the base, but Washington had nothing to do with the construction or operation of the prison. However, guards working in the prison often reminded American prisoners how ironic it was that they were detained in a place their government had built to detain Al-Qaeda suspects.

When I arrived at the prison in mid-2015, the majority of the prisoners in the facility were suspected members of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Eventually, under the Houthi-Saleh alliance, the prison population would diversify to include American, European and Yemeni journalists, various other US and foreign nationals arrested in Sana’a, members of the Baha’i religious minority and political activists, including Dr. Abdulkader al-Gunaid.

The white-haired man and the soldier walked me into the prison, making sure I didn’t trip going up the stairs to the front door. After emptying out my pockets and taking my sandals, belt and jacket, two prison guards untied the cloth from my wrists and replaced it with metal handcuffs. They unlocked a heavy gate and walked me barefoot down a dim corridor lined with cells on one side.

Near the end of the hallway, they pulled off my blindfold and swung open the steel door to one of the cells. Three Yemeni faces stared back at me: a frail young man from Sana’a, a stocky guy in his 40s from Abyan and an energetic, broad-shouldered 20-something from Aden.

Our cell was about 6 x 15 feet with a waist-high concrete wall in one corner that partially blocked the in-floor toilet from the rest of the room. Above the toilet near the ceiling, a small pipe channeled fresh air, sunlight and sounds into the cell. When a missile exploded, the pipe emitted a faint popping sound from the change in air pressure. Some former prisoners later told me that when missiles struck near the prison the pressure from the blast was so strong they temporarily lost their hearing.

Locked inside the concrete cell, my initial concern was to convince the guards to bring me the prescription medication I had been taking daily for depression and anxiety. Missing even one dose was an agonizing ordeal that I had experienced more than once in Sana’a when a refill from the US was delayed and a box of the expensive drug wasn’t available from a local pharmacy. The longest I had gone without it was only a couple of days, but it left me immobilized from what felt like the flu and a painful-sensitivity to light, sound, and movement of any kind.

I told the guards where to find the prescription bottle in my suitcase at my house. Hours later, a guard returned with a couple of pills that looked like Tylenol. I wrote the name of the drug on a piece of paper and, with the help of the English-speaking Adeni cellmate, stressed that I would get very sick without it. Nobody seemed to care. The guards ignored repeated requests, and it soon became clear that they had no intention of retrieving the medication. That night, we fell asleep to the high-pitched screams of a prisoner, who for some reason was called “Casper.” My Adeni cellmate told me he’d lost his mind. Years later, another former prisoner told me Casper was an Al-Qaeda suspect who believed he was possessed by jinn.

Early the next morning, the cellmate from Abyan woke the rest of us up in a panic. His body, arms and legs were rigid and trembling. He groaned in pain and tried to sit up. The Adeni shouted for a guard, pounding on the steel door until Abu Hamza, a potbellied interrogator with an abnormally large head, appeared. Soon another man entered the cell and jabbed a needle into Abyani’s arm, connected it to a bag of clear fluid and left. Within minutes, the injection site on Abyani’s arm had ballooned to the size of a grapefruit, inducing another round of panicked cries for help. The same man returned with a scowl on his face, clearly annoyed with the situation, and ripped out the needle. When he was satisfied he had found a vein, he handed Abyani the bag and left.

Later that day, as I was settling into my cellmates’ routine, Abu Hamza flung open the door and signaled for me. He was wearing a black balaclava mask, accentuating the size of his head. I jumped up with nervous excitement, believing they were about to release me. Instead, he and a guard with an AK-47 moved me to a solitary cell. With no ventilation pipe, or any other connection to the outside world, the room felt like a bunker or a tomb, something buried deep down in the earth where no one would ever find me.

By this point, I was starting to feel the effects of missing the morning dose of my medication. A headache morphed into a migraine, my muscles started to ache and I felt shocking sensations whenever I moved my eyes, a common withdrawal symptom. To counteract the sense of doom enveloping my serotonin-starved brain, I paced around the cell and did some pushups. Then the lights turned off and my motivation vanished. Complete blackness. Alone and afraid of where my waking thoughts might lead, I tried to sleep, only to be jolted awake by the bright lights overhead, which flicked on whenever I started to doze off, or the heavy metal gate outside my door that screeched open and slammed shut at all hours.

In between twice-daily deliveries of bread and beans, prison guards shackled my wrists and ankles and shuttled me to and from interrogation rooms in which Abu Qais, a longtime NSB agent and Saleh loyalist, ordered me to confess that I was Al-Qaeda, a CIA agent or helping Saudi Arabia bomb Sana’a – sometimes all in the same breath.

I have no idea how long it went on like this. With no source of natural light inside the cell, and reeling from the effects of stopping the medication cold turkey, I lost track of time. My thoughts drifted, cracked, and bent in on themselves.

****

The next several days are beyond the reach of memory. Some scenes I recall, others were told to me years later by other prisoners. Sometimes the puzzle pieces seem to line up, sometimes they don’t. But my body remembers what my mind cannot.

At some point, I was transferred back to my original cell with the three Yemenis. One day, I’m not sure which, we were sitting in a circle on the floor eating handfuls of rice when Abu Shamekh, a senior Houthi guard, opened one of the slots in our door. Abu Shamekh liked to taunt people and get prisoners to turn on one another. And that’s exactly what he did. He slid two wooden clubs through the slot and ordered the others to beat me with them, or so I was told. I have no memory of this.

After that I was then transferred back to the solitary cell, where a guard forced me to stand up and sit down for about 10 minutes. It was a common form of punishment that could go on for hours, but I wasn’t able to carry out the commands. I remember the act of standing and sitting, but I don’t recall feeling any pain, though for some reason I couldn’t straighten my back once my feet were under me. In a daze, I kept trying to stand upright, but my back wouldn’t respond.

My next memory was of Abu Hamza shouting at me through one of the slots in my door, asking me what was wrong. I lay on the floor in paralyzing pain. Every time I tried to move, my diaphragm contracted. He kept shouting as I struggled to piece together what was happening. He disappeared and my mind started to drift.

I managed to crawl several feet across the grimy tile floor to the faucet and toilet in the corner, where I could wait out whatever was happening to me. Prisoners in neighboring cells said they heard me crying out for at least two consecutive nights before the guards took me away, presumably to a hospital. Maybe I did, but the memory is gone. At some point, the next day or the day after, the guards brought me back to my solitary cell. I’m told I groaned and made animal noises from the pain, but like so much from these days my mind is empty. At some point, the guards again took me out of the prison. Another prisoner remembers riding to a hospital with me in the back of a van. I was tied to a plastic stretcher with handcuffs around my wrists and ankles.

I awoke inside an MRI machine at the Saudi-German hospital in Sana’a. An elderly Yemeni doctor standing at the foot of the plank I was strapped to explained that the machine was scanning my body for injuries. I don’t recall the deafening bangs and clicks that accompany MRI scans, but I do remember the doctor. Then I blacked out.

Some time later I regained consciousness in a hospital room still strapped to the plank. Four Houthi gunmen with AK-47s sat in the corner. Three of them, probably high school-aged, stared at me. I tried to avoid eye contact, afraid that they might mistake a wince of pain for hostility. The oldest of the four, who might have been in his early 20s, seemed to be the only one who empathized with my condition. He alerted the hospital staff when my facial contortions signaled the pain was too much to bear. A nurse would then inject a vial of pain killer into the IV tube in my arm, providing a moment of relief before I passed out again.

Several times, the doctor from the MRI machine entered my room with a colleague in a wheelchair, and pleaded with the guards to send me out of Yemen for emergency surgery that couldn’t be performed there. “Without surgery he will die or be paralyzed like him,” he shouted, pointing to the doctor in the wheelchair.

Images from CT and MRI scans dated May 27 and 28 showed fractures and crushing injuries in the mid-lower part of my back, where the thoracic and lumbar sections of the spine connect. Bone shards from the crushed vertebrae were dangerously close to touching my spinal cord.

On June 1, the guards drove me to the airport, where a plane was waiting to fly me to Oman’s capital Muscat. The doctor who had harangued the guards to release me accompanied us to the airport. As I was being transferred to the plane on a stretcher, he stood over me with a concerned look. “Not all Yemenis are bad people, Mr. Casey,” he said, holding my hand in his.

****

After a week in Muscat, I was flown to Seattle, Washington, where surgeons replaced my L1 vertebra with a prosthetic cage and fused 11 vertebrae in total during nine hours of surgery. At that point, I had no idea how the injury had happened. The surgeons guessed that I had been in a high-speed car crash or had fallen several stories to the ground. Another theory was that the prison I was in had been hit in an airstrike, but the surgeons ruled that out because I didn’t have any other broken bones, scrapes or other injuries they would expect to see in that type of situation.

In the months and years after my release, former prisoners slowly sketched in the details of my detention: the beating at the hands of my cellmates, the nights in solitary, and how I ended up in the hospital. Based on those accounts, my best guess is that my spine was fractured during the beating – maybe I fell against a corner of the concrete wall in the corner of the cell, or maybe I was struck just right with a wooden club – and then it was aggravated during the exercises the guard forced me to do.

Recovery has taken years. The first six months after surgery were focused on building up the strength to walk again, then how to maneuver in and out of the passenger seat of a car. Later, I learned how to hop on and off busses without falling over. Heavy painkillers and valium helped blunt the physical pain during those early days. But they also numbed me to the emotional trauma of my final three weeks in Yemen and the uncertainty around how crucial moments had unfolded.

Since my release, I’ve heard the stories of a number of people who were held at the same prison. The torture that guards inflicted on them included mock executions, electrocution, strangulation, and beatings with fists, boots and wooden clubs. They tied prisoners’ limbs in painful positions for hours, forced them to sit in cold baths during winter, and threatened to tell prisoners’ Al-Qaeda cellmates that they had helped US drones target AQAP.

At any given moment, most prisoners were suffering from some form of disease or ailment: scabies from mites, panic attacks, pneumonia, PTSD, heart disease, as well as concussions and other torture-induced injuries. Jamal Ma’amari, a tribal sheikh from Marib, was paralyzed from the waist down during beatings by Houthi interrogators who abducted him in March 2015. He spent three years in prisons, including the one where I was held, before he was released. Several prisoners committed suicide. Others who survived suicide attempts were punished for it. Five months after I was released, an American prisoner died in the solitary cell where I was held. An autopsy report concluded that he died of asphyxia. A lawsuit filed by the prisoner’s family said he was strangled to death.

For years I kept my distance from Yemen. I needed time. Time to heal and time to process what had happened and how to live with it. But in 2019, I started transitioning back to reporting on Yemen. What happened to me was not unique, not for those who have been imprisoned by the Houthis. Indeed, my experience paled in comparison to what Yemeni prisoners have endured under the Houthis. My nationality helped get me out of the country when I needed to go. I had access to doctors, nurses, mental health therapists, as well as medicine to recover from the traumatic injuries. Many Yemenis who make it out of prisons aren’t in a position to leave the country, obtain medical help or even speak about what happened to them out of fear that they or their family members will be thrown back into prison. But I can speak, and so I am. Mine is but a single story, yet the experience is far from mine alone.

Casey Coombs is an independent journalist focused on Yemen and a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. He tweets @Macoombs

Roundtable Discussions

Biden Takes Over: Advice and Expectations for a New US Administration

US President-elect Joe Biden has made clear that his administration will cut off support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen. Yet it is not clear what US policy toward Yemen will look like under the Biden administration.

Washington’s Yemen policy, long driven by counterterrorism and broader regional interests, has substantively remained unchanged through the past three US administrations. At times, drone strikes have intensified or direct military ground operations have eased, but Yemeni internal issues — political, economic and security — consistently have been left to Saudi Arabia. In terms of the Yemen War, Washington has staunchly supported Saudi Arabia, in the UN Security Council and in supplying weapons and logistical support to carry on the fight against the armed Houthi movement.

Midway through the Trump administration, however, US support in Congress for continuing the status quo began to waver considerably. The October 2018 pre-meditated torture and killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a US resident and familiar face in Washington, inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul shocked lawmakers. Opposition to arms sales grew along with concerns about Saudi Arabia’s role in Yemen’s war. US President Donald Trump never faltered in his support for the Saudi leadership, but a field of Democratic Party challengers began questioning the Saudi relationship, US priorities in the Gulf and the impact of US decisions on Yemen. One of them will move into the White House in January, and while Biden has pledged change, he hasn’t made clear whether the United States will simply step back from the fighting or invest diplomatic capital in Yemen. Four experts discuss what policy the Biden administration should adopt in Yemen.

This roundtable is part of a series of publications by the Sana’a Center examining the roles of state and non-state foreign actors in Yemen.

Biden’s Triple Challenge in Yemen

By Stacey Philbrick Yadav

When it comes to Yemen – as with so much else – the incoming Biden administration will face a trio of overlapping challenges. It will be tasked with reversing damaging policies adopted by the Trump administration, re-engaging with multilateral institutions and partners, and reimagining its relationship to the conflict in Yemen. This will require a break from the policies of the Trump administration as well as from at least some of those of former President Barack Obama.

Over the past four years, Trump has shown tepid and largely rhetorical commitment to multilateral peacebuilding efforts in Yemen, undercutting this work through ongoing military cooperation with the Saudi-led coalition, and his most damaging policies may be yet to come. Since losing the election, the Trump administration’s proposed sale of US$23 billion in military equipment to the UAE stands to tip the balance of power within the coalition itself in a way that could needlessly complicate already febrile escalation in the South. The administration has also begun publicly weighing a move to classify the Houthi movement as a terrorist organization, suggesting that the Trump administration is divesting from diplomacy and seeking a military resolution to a conflict that most Yemeni parties agree requires a negotiated end.

The Trump administration has also downgraded diplomacy and disengaged from core humanitarian projects in Yemen, leaving millions at risk. While the US is not the sole driver of the collapse of donor commitments, the rollback of essential relief programs in the region’s worst humanitarian disaster is abetted by the Trump administration’s attack on multilateral forms of accountability for civilian targeting. In recent months, the Group of Eminent Experts (GEE) that reports to the UN Human Rights Council has called on the Security Council to refer parties to the war to the International Criminal Court on the basis of documented targeting of infrastructure and the obstruction of aid delivery; not only has the US not supported this effort at accountability, it has worked to effectively criminalize the ICC itself.

President-elect Biden’s work will not be restricted to repairing or reversing this damage, however; he also has a unique opportunity for a broader rethinking of US policy in and toward Yemen. While it is disappointing that it took the murder of a single Saudi citizen – Jamal Khashoggi – to provoke congressional demands for a more accountable foreign policy in the Gulf, Biden will be making policy with a very different Congress than the one that he dealt with as vice president.

Congressional pressure on the US-Saudi alliance contributed to breaking a major diplomatic impasse in Stockholm in 2018, and it is clear that bi-partisan challenges to military sales to Gulf allies continue to exist even in this divided post-election context. Now it is time to use this congressional awareness of the costs of (and US implication in) the war to press for a renegotiation of the diplomatic framework. Without the risk of a presidential veto, it should be possible for congressional and executive branches to work beyond the binary approach of UN Security Council Resolution 2216.

While the outgoing administration has worked to block Biden’s team in unprecedented ways, the trio of challenges outlined here is one of philosophy as much as planning – it requires rethinking the United States’ approach to Yemen before all else, and that is a challenge that a new team can and should undertake now.

Stacey Philbrick Yadav is associate professor of political science at Hobart and William Smith Colleges and a non-resident fellow at the Crown Center for Middle East Studies at Brandeis University

Create Leverage and Use It, On All Parties

By Baraa Shiban

As the conflict in Yemen enters its seventh year, it is time for the US and a new Biden administration to adopt a different approach. Although there is a proxy element to the war, it is essential to approach the conflict through a Yemeni prism.

First, the United States must create leverage to get the parties to the negotiating table. Neither the National Dialogue Conference that followed the Arab Spring uprising nor four rounds of UN-sponsored talks have produced concrete results. The main reason for this is the international community’s failure to create leverage over the Houthis in a way that would force them to the negotiating table. A Biden administration could, for example, make any US re-engagement with the Joint Comprehensive Plan Of Action (commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal) contingent on Iran using its influence to push the Houthis to compromise. The US should, in turn, use its leverage to do the same with the Saudis and the Yemeni government.

Second, counterterrorism alliances are hindering state institutions. The Biden administration should prioritize reigning in the United Arab Emirates and immediately make any ongoing partnership with the UAE contingent on it ending its support to militias and perpetrators of human rights abuses in South Yemen. The UAE’s claimed counterterrorism operations in Yemen have directly undermined the Yemeni government’s ability to build strong, local state structures. The Emirates’ support for militias has weakened security throughout the south and led to the secret detentions and assassinations of those who oppose the UAE, eroding efforts to reunite Yemen.

Third, drone strikes are not helping Yemen. A Biden administration should bring them to an immediate end in Yemen and cancel plans announced in November to sell the UAE weapons-ready MQ-9B drones. The intelligence behind drone strikes is often flawed, and their lack of accountability only gives groups such as Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and the Islamic State ammunition with which to recruit and sow discord.

Finally, the Biden administration should reiterate its support for President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s government while tying this backing to certain benchmarks that ensure the Hadi government is transparent and held accountable for its actions. The US should not hesitate to impose sanctions against corrupt officials profiting from the ongoing conflict. This should also apply to the Yemen government’s partners, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Baraa Shiban is MENA caseworker for the human rights group Reprieve, conducting field investigation on the US drone program, former adviser to the Yemeni embassy in London and a youth representative in the Yemeni National Dialogue

A Step Toward a Strategy

By Gregory D. Johnsen

President-elect Joe Biden has made it clear his administration will end US support for Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen. That is a necessary and wise step, but one that must be taken as part of a broader strategy to end the war in Yemen and, slowly, piece the country back together again.

Cutting off US support absent a broader policy will do little but rupture a relationship with Saudi Arabia that is in need of repair, institutionalize the Houthi coup in Sana’a and, ultimately, lead to the break-up of Yemen as a single state. Such a Humpty Dumpty scenario in which Yemen fractures into various zones of control will have enormous and far-reaching consequences for US national security.

Upon taking office, the Biden administration should inform Saudi Arabia of three things. The war must end, US support for Saudi Arabia will end, and the US will do everything in its power to help Saudi Arabia find a workable peace. Saudi Arabia needed US acquiescence to begin this war and it will need US help to end it.

Various UN special envoys have had nearly six years to find a comprehensive agreement in Yemen. They have not been able to do so. Not because they are not skilled diplomats, but rather because the UN lacks the leverage to force the various parties to the table and then insist that they implement what they agree upon. The United States has that leverage, at least with the Saudis.

As part of its diplomatic effort, the United States should broker three-party talks between the internationally recognized Yemeni government, the Houthis, and Saudi Arabia. In these talks, the US should insist upon Yemen’s territorial integrity as well as the unity of the Yemeni state.

The Houthis have to understand that they are negotiating to be part of the state, not the state itself. Saudi Arabia must understand that the Houthis will have a role in Yemen’s future. President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi must understand that a repeat of the Kuwait talks in 2016 will not be tolerated. Either he is part of the solution or he is part of the problem.

The US has already got it wrong twice in Yemen. Under the Obama administration, the US outsourced Yemen’s supposedly democratic transition to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Cooperation Council. A few years later, when that transition predictably collapsed, the US compounded the error by backing Saudi Arabia in a foolish and unwinnable war, which did little but drive the Houthis closer to Iran.

There is no time to lose. Already, the Houthis are acting like a nation-state, appointing and receiving ambassadors. The Southern Transitional Council is looking to secede, and various pockets of the country have gained significant autonomy over the last few years.

A fractured Yemen will present a number of challenges to the US from the vast amounts of humanitarian aid that will need to flow into the country to the security of shipping lanes and a potential renewed threat of terrorism.

A renewed diplomatic effort, led by the United States, may well be the last chance for a unified Yemen.

Gregory D. Johnsen is an author, editor of the Yemen Review and a non-resident fellow at the Sana’a Center and at the Brookings Institution

Biden’s Options may be Limited by a Houthi FTO Designation

By Thomas Juneau

According to media reports, the Trump Administration plans to designate the Houthis as a terrorist organization prior to leaving office in January 2021. Houthi governance in northwest Yemen is increasingly corrupt, authoritarian and violent, and war has brought the group steadily closer to Iran. It is therefore the right policy for the United States, strategically and morally, to oppose the Houthis. Yet designating the Houthis would be counter-productive: it would hamper the already difficult work of humanitarian organizations trying to deliver much needed aid in Houthi-controlled parts of Yemen, where 80 percent of the population is reliant on aid. It would also complicate the already steep hill the faltering peace process faces. It would, moreover, only marginally hurt the Houthis.

The main consequence of designating the Houthis would be to tie the hands of the incoming Biden administration. Supporters of designating the Houthis argue that it would provide the next administration with additional leverage in an eventual peace process: it would allow Washington to extract more concessions from the Houthis in exchange for delisting them. This has some truth in theory, to the extent that it is not a bad idea to accumulate assets that can be traded away in advance of future negotiations. Because the Houthis hold the upper hand in the balance of military power on the ground in Yemen, it is, again in theory, appropriate to build leverage against them.

In practice, however, it is unlikely that the benefits outweigh the costs. At some point in the future, Washington might assess that delisting the Houthis is necessary to see progress toward peace. Yet delisting the Houthis would be far easier said than done, as the move would inevitably attract significant opposition from Saudi Arabia and inside the United States. Procedurally, it would be straightforward; yet as other examples of sanctions that acquire a life of their own and become very difficult to lift show, it is the politics that would be challenging, both domestically and internationally.

This is entirely consistent with a central aspect of hawkish foreign policies toward Iran: the intent to tie the hands of future governments, to lock them into the existing confrontational dynamic and sabotage eventual efforts at engaging Iran or the non-state armed groups it supports. Such punitive policies are, to some extent, necessary: Iran is a rival to the United States and its allies and partners, and its policies are responsible for much instability in the Middle East; it is thus necessary for the US to work to contain Iran. But when sanctions are used like a hammer in search of nails, as opposed to a more surgical tool, the costs come to exceed the benefits. These unnecessary, excessive sanctions do not make engagement impossible – sanctions can, in theory, be lifted – but they do make it more complex and politically costlier. As a result, the negative – and clearly intentional – side-effects (in this case, hampering the delivery of aid and creating an obstacle to peace) are also perpetuated.

Thomas Juneau is associate professor at the University of Ottawa’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs and a non-resident fellow at the Sana’a Center

Trump’s Endgame: Weighing a Houthi FTO Designation

As US President Donald Trump’s administration winds down, reports have emerged that Washington is once again considering the idea of designating the armed Houthi movement, Ansar Allah, as a foreign terrorist organization. Such a move would criminalize most interactions with the Houthi movement conducted without US government waivers.

The United States, a key international actor in the Yemen conflict and strong supporter of the Saudi-led coalition, hasn’t received public support from its Western allies for such a designation. On December 8, the United States imposed terrorism-related sanctions on Hassan Eryloo, the recently-appointed Iranian ambassador to the Houthi government in Sana’a. The US claims that Eyrloo is an officer in Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps – Quds Forces. It is unclear whether the sanctions targeting Eryloo were linked to the planned designation of the Houthi movement, or indicate that the US may be reconsidering its plans.

Sana’a Center experts respond to the prospect of a broader FTO designation and what impact such a parting shot by the Trump administration — regardless of whether intended more for the Houthis or the Iranian regime that supports them — could have on the Yemen conflict, and on Yemeni civilians.

This roundtable is part of a series of publications by the Sana’a Center examining the roles of state and non-state foreign actors in Yemen.

Trump’s Parting Shot Against Iran Would Be At Yemen’s Expense

By Waleed Alhariri

Designating the armed Houthi movement, Ansar Allah, a terrorist organization is an attempt by the Trump administration to ratchet up its ‘maximum pressure’ campaign on Iran. For Yemen, and attempts to peacefully end six years of war, it would be a significant setback.

A US foreign terrorist organization (FTO) designation would limit Western diplomatic access to the Houthis. US diplomats, for example, were involved in brokering mini-deals related to prisoner exchanges facilitated by Oman. Without US pressure — such contact is barred under an FTO designation — the Houthis would have more room to stall any UN calls for compromise. A more effective approach would target individual members of the group, as the UN sanctions committee recommended in its January 2020 report and, the Sana’a Center confirmed, will do so again in an upcoming report.

According to an Arab diplomat familiar with the lobbying efforts, the Yemeni government has sought the FTO designation only for the Houthis’ military wing as a way to disempower the group militarily but allow for its politicians to negotiate a political settlement. The diplomat told the Sana’a Center that the Emiratis and Saudis, who led the Arab military coalition against the Houthis, pushed for a broader designation, one that would include the group as a whole.

Governments of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates swiftly designated the Iranian-backed Houthi movement a terrorist group in 2014, after the Houthis led an armed coup and took over the capital, Sana’a, and surrounding governorates. Since then, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi along with the internationally recognized government of Yemen — and, on a separate track, Israel — have lobbied first the Obama administration and then the Trump administration to designate the Houthis as an FTO.

As in the past, calls for a Houthi FTO designation flare when the United States, Arab Gulf countries and Israel decide to apply pressure on their common adversary, Iran. In media briefings and in UN statements, the Trump administration consistently has used Iranian support for the Houthis to condemn and pressure Iran, including the submission of a draft council resolution in February 2018 concerning illegal use of Iranian-made missiles by the Houthis in Yemen. That resolution was blocked by a Russian veto, but the administration’s pressure campaign against Iran continued to use the Houthi missiles to justify harsher action against Iran, including an FTO designation. It dropped these plans amid criticism from humanitarian groups who feared it would disrupt their responses, and from the UN envoy’s office, which enlisted UK help in convincing the Americans it would have a chilling effect on UN negotiating efforts.

Today, Israel and Gulf Arab countries are concerned a Biden administration will revive a version of the Obama-era Iran nuclear deal. That possibility intensifies the campaign against Iran, as seen in the recent assassination of a top Iranian nuclear scientist as well as the revived Houthi FTO plan. And as US President Donald Trump leaves office, he appears intent to score a final point against Iran, at Yemen’s expense.

Waleed Alhariri is head of the New York office of the Sana’a Center, whose work focuses on Yemen issues at the United Nations

This Political, not Moral, Decision Risks Strengthening Houthis

By Maysaa Shuja al-Deen

Although modern Yemeni history has witnessed several violent ascensions to power, the Houthi rise has been particularly depressing because it followed the 2011 uprising, which was premised on peaceful struggle and sought to eliminate tyranny by individuals or groups and to establish a government accountable to all citizens. The Houthis, however, chose to impose their will through violence even though after the uprising they, too, had access to the means to participate politically and compete for support.

What the Houthi movement has accomplished in the years since — through blowing up the homes of its rivals, collective punishments such as the siege of Taiz and the arbitrary use of landmines — undermines society’s attempt to break the cycle of violence. It has awakened historical vendettas and divisions. So it is little wonder some Yemenis celebrated Washington’s plan to officially designate Ansar Allah, the Houthis, a terrorist organization as an overdue international recognition of the group’s extreme violence and the major setback it has dealt Yemen.

Welcoming that decision, however, overlooks several key factors. First, the designation is based entirely around US security and interests. It is a political decision aimed at Iran, the Trump administration’s “last hurrah” in this regard, rather than a moral indictment of the violence the Houthis have perpetrated against their own citizens. Second, this decision allows the Houthis to affirm their narrative that the ongoing conflict is an anti-imperialist struggle against the global superpower that is the United States. That, in turn, could embolden their rhetoric and strengthen their organization by gaining the sympathies of others who oppose American hegemony, including Western activists and journalists. Another risk of the designation is that it will drive the Houthis closer to other actors targeted by similar US actions, including Hezbollah and the Iranian and Syrian regimes, as well as toward Washington’s international rivals, China and Russia.

The problem with the US classification of the Houthis does not lie in whether the movement is morally worthy of such condemnation, but rather the implications of this decision. Whenever this classification has been used, whether targeting regimes as state sponsors or terrorism or groups such as Hezbollah and Hamas, it has done nothing to undermine the control these regimes and groups have over their people. On the contrary, it can contribute to the consolidation of their power and increase the persecution they practice by providing excuses for the poor level of services they provide and for people’s deteriorating livelihoods. Furthermore, targeted state and non-state actors can find ways around sanctions and blockades; their control over what few channels remain with the outside world also can increase their control over their isolated societies. For the people living under their control, a state of economic isolation and deprivation exacerbated by sanctions only further exhausts and depletes the local society, diminishing its ability to resist the tyranny under which it resides.

Maysaa Shuja al-Deen is a non-resident fellow at the Sana’a Center whose research includes the roots of radical Zaydism

Who Will Benefit from the FTO Designation of the Houthis?

By Abdulghani Al-Iryani

While conflict situations are usually volatile, political dynamics always strive toward equilibrium. Disrupting an equilibrium triggers another round of volatility and violence, as parties to the dynamic strive for a new balance. The reported plan by the Trump administration to designate Ansar Allah, commonly known as the Houthi movement, as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO) will disrupt several equilibriums in the Yemen conflict:

Internal Ansar Allah equilibrium: Ansar Allah is highly centralized and united by the ideological and religious loyalty of its members to their wali al-alam, or divinely ordained leader of the time. Still, its rapid expansion over the past few years has fractured the Houthi movement along ideological and practical lines. The two key broad factions that have thus far balanced each other are the pragmatic leaders, many of whom have become fabulously wealthy and are willing to compromise to protect the substantial gains they have had so far, and the ideologues, who view their control of Yemen as a stepping stone to their true mission of taking over Mecca, Medina and beyond. The FTO designation will be a shot in the arm for the ideologues and their strategy of pursuing continued escalation against Saudi Arabia.