Executive Summary

This three-part report by the Sana’a Center examines the multi-faceted relationship between tribes and the state in Yemen. It shows that this relationship has long been a complex one, with the relative power of each waxing and waning. However recently – starting before the current conflict began – a protracted period of co-option of tribal leaders into the state apparatus has led to both a strengthening of the wealth and influence of some individual sheikhs, and to a weakening of their links to their tribal members. Under former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, this policy gave rise to a tribalization of the state, with a consequent, multi-faceted impact on its functioning. This led to changes in the structure and influence of the tribes, accelerated by years of conflict and the rise of the Houthi movement. These factors – along with an economic crisis – have left tribal customs and laws shaky, with an absence of both traditional and state authority leading to fractured and more dangerous communities.

This has had an impact on women in particular, whose status in traditional societies has been undermined – although women continue to play key roles in mediation and peacemaking.

Now, the tribes stand at a crossroads. Exhausted by years of war, crushed politically in Houthi controlled areas and bearing the brunt of the fighting in those under control of the internationally-recognized government, they have paid a huge price in the current conflict. This report looks at how this came about, analyzing the historical, social, political and cultural trends behind the embattled state-tribe relationship in Yemen.

Part I gives an overview of the historical interactions between the tribes and Yemen’s governing authorities, from the mid-19th century to unification under the regime of President Saleh. Part II focuses on tribal codes as alternatives to statutory laws, including various views on their development and implementation. Part III examines the role tribes have played in conflict in Yemen, from the 2011 Revolution through to the present day.

Part I: From the Ottomans and British to Autocracy

The Long History of Yemen’s Tribes

Tribal social structures have informed events in Yemen since well before the founding of the republic in 1962. Indeed, the tribes have greatly contributed to shaping Yemeni history, including the formation and nature of various governments. In turn, attempts at state-building in Yemen have influenced and changed the nature of tribal formations. Which of these processes has had more effect on the other is an open question and one that will be examined during the course of this analysis.

The definition of a tribe in Yemen can be loose and nonspecific. It can refer to a simple grouping of families that inhabit a specific geographical location, or a union of branches of tribes that share a common tribal name. “Tribe” can thus denote kinship or a political or economic relationship. Tribal structures are not based on a single clan or tribe, but rather include multiple kinship and spatial tribal divisions linked to each other by distinct relationships.[1] These complex networks of families or clans are intertwined together through common lineages, customs and alliances. Families and clans belonging to a particular tribe are also bound by the common traditions that regulate relations within and between tribes.[2]

The tribal map in Yemen has changed throughout history. Tribal confederations have shrunk and expanded, with some tribal branches shifting their affiliation to other tribes for protection and alliance. At present, there is general agreement that in Yemen there are five major tribal confederations.[3] The two largest are the Hashid and Bakil confederations, based in the areas north of the capital Sana’a, covering Sana’a, Amran, Sa’ada, Al-Jawf and parts of Marib governorate. The next three largest confederations, Madhaj, Himyar and Kinda, are spread across the remaining areas of the country.[4] In places, confederations intersect and overlap, while there are also regions with no strong tribal structures, such as Taiz in central Yemen and Aden in the south.

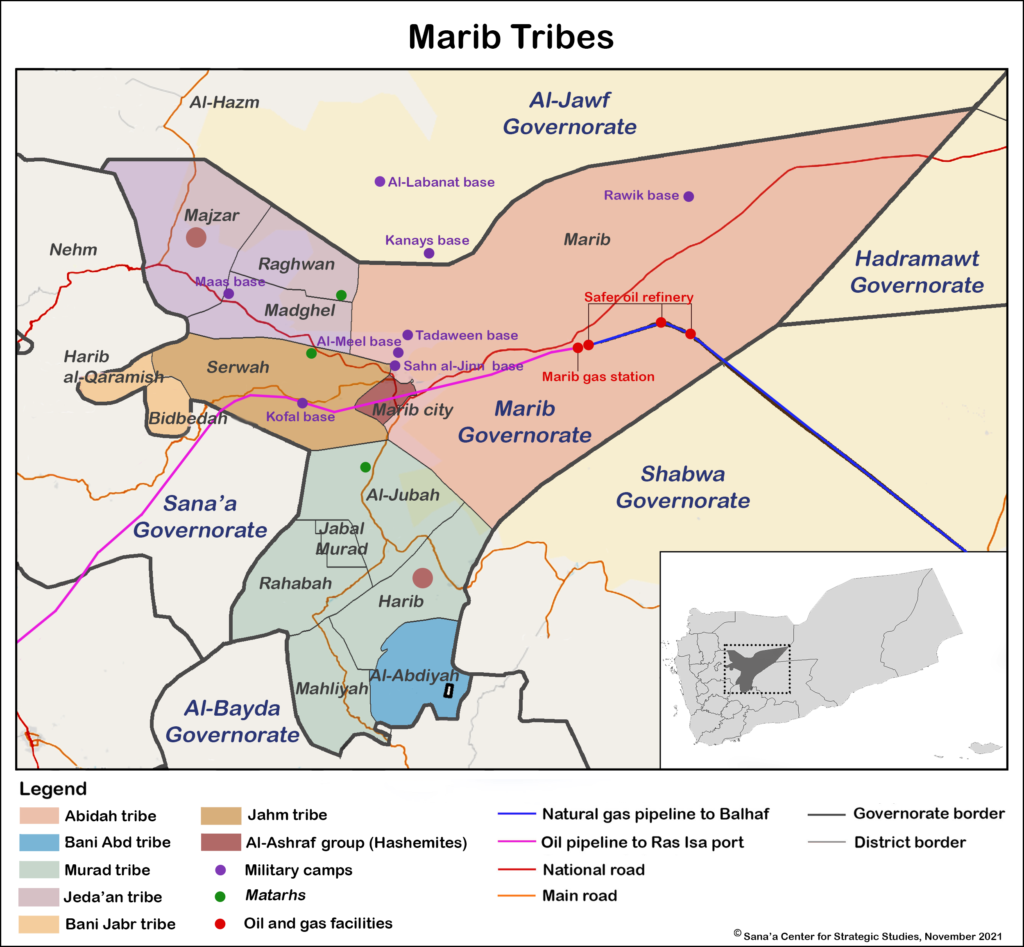

These tribal confederations consist of several smaller tribes or sub-tribes. The Hashid, for example, consists of four main ‘original tribes’, Al-Usaimat, Adhar, Banu Suraim and Kharef.[5] Within these branches are smaller sub-branches. The Bakil confederation consists of about 31 tribes, with the most prominent sub-confederations being the Dahm (eight sub-tribes) and the Wael (seven sub-tribes).[6] The Madhhaj confederation includes, most prominently, the Murad tribe based in Marib and Al-Bayda governorates, which includes the Talya, Walid Jamil and Al-Hada sub-tribes. These sub-tribes can be divided even further; for example, the Talya tribe includes members from the Banu Seif and Buhaibah families, and so on.[7]

Tribal structures are similar in the south and north of the country, although with differences related to demographics and geography, as well as historical, political and economic changes. These differences also include a rough geographical division between Yemen’s two dominant sects: Zaidi Shias and Shafei Sunnis.[8] The former are based in “Upper Yemen, or the (Zaidi) plateau, encompassing the governorates of Sa’ada, Amran, Al-Jawf, Sana’a, Hajjah, Dhamar, Marib and Al-Mahwit. Most tribes in these governorates belong tribally to the Hashid or Bakil confederations. Shafei Sunnis are based in “Lower Yemen”, or the central plateau and (Shafei) plains. In Shafei areas, the majority of tribes belong to the Madhhaj, Himyar or Hadramawt tribal unions.[9] This division is not rigid, however, as there was considerable mixing between the two sects in the decades that followed the founding of the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) in 1962. The capital, Sana’a, for example, appears to have a Sunni Shafei majority at present.[10]

Tribes and the Imamate in Northern Yemen

The Second period of the Ottoman Vilayet of Yemen lasted from 1872 until 1911, but failed to impose full control in the north, where Zaidi imams and tribes continued, at times, to challenge the Ottomans militarily, but, at others, cooperated with them. The Ottomans were more able to control central areas, such as Tihama and Taiz, where they collected taxes, imposed conscription, and generally weakened tribal structures, although there was sometimes violent resistance, as occurred at Al-Maqatara in Taiz,. The northern highlands around Sana’a, however, remained under the control of successive Zaidi statelets that were hostile to foreign control. These maintained much of their tribal character tribes, with hereditary imamates relying on tribal customs to govern.

In 1904, Imam Yahya bin Hamidaddin, a descendent of the Zaidi imams that had successively ruled Yemen, led the last revolt against the Ottomans. The revolt lasted two years and exhausted the Ottoman forces, leading to negotiations that ended with the signing of the Treaty of Daan in 1911. The imam recognized Ottoman jurisdiction over Yemen and the Ottoman state recognized the right of the imamate to rule over the Zaidi sect.[11] The two sides had agreed on 10 years of reconciliation and peace, during which the Yemeni state was to be built under the supervision of the imamate. But the collapse of the Ottoman state in World War I granted the imam the opportunity to establish the independent Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen.

Imam Yahya had sought help from the tribes in his long war against the Ottomans.[12] He was a Hashemite and sayyid, who claim that they are descendants of the Prophet Mohammed. In Zaidi doctrine this status granted him the right to rule, with the tribes supporting this claim. The alliance between the imam and the tribes against the Ottoman presence in northern Yemen did not last long, however. The first turning point was when the imam neglected to consult tribal leaders during negotiations over the Treaty of Daan. The Hashid and its leadership were “supporters, not subjects” of the imamate, according to the memoirs of Sheikh Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar (1933-2007).[13] This meant that they had some independence in their tribal lands, such as the right to collect taxes.[14] After Imam Yahya inherited part of the military establishment from the Ottoman regime, his approach toward the tribes became more confrontational as he sought to turn them into subjects.

The years following the establishment of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom witnessed attempts by the imam to confront the tribes and curtail their power, partly out of a fear that they might turn against him. After 1919, battles between imamate and tribal forces were fought in central regions and in the environs outside Sana’a. The result was a string of victories for Imam Yahya. These included the imam’s victory over the Al-Maqatirah tribe in 1920, over the Hashid tribes in 1922 and over tribes from Al-Jawf in 1925.

To keep the tribes in line and loyal to the imamate, in 1928 Imam Yahya adopted a system[15] in which each fakhd (subgroup) of a tribe was obliged to send representatives to be held by the imam as a hostage. According to Sheikh Abdullah al-Ahmar’s memoirs, Hashid sheikhs handed over two hostages to the imam as a guarantee they would not rebel against him. If hostages died, they were obliged to be replaced.[16] Following the imamate’s early victories against the tribes and the establishment of the hostage system, tribal opposition to the imamate decreased, with many tribes becoming supporters and fighters for the imam.

Under successive imams, the Mutawakkilite Kingdom ruled the northwestern part of Yemen from 1918 to 1962. This state did not have modern and efficient institutions, however, military or civil. There was no ministry of finance until 1948,[17] while a ministry of health was not established until 1957 and initially had only three employees.[18] The capital of the kingdom was Sana’a until 1948, when it moved southward to Taiz.

A tribe in northern Yemen during the 1920s-1930s could be described as a stand-alone social component that maintained a degree of self-government. The geographical borders of some tribal federations expanded and others shrank as the loyalties and interests of smaller tribes shifted.

Conflict between tribes and the imamate remained a regular feature of political life in northern Yemen. Tribal leaders participated in several revolts aimed at overthrowing the imam. One example was the Constitutional Revolution of 1948, in which the aging Imam Yahya bin Hamidaddin and two of his sons were killed. This was led by Abdullah al-Wazeer, a military leader, and Ali bin Nasser al-Qardaei, the paramount sheikh of the Madhaj Murad tribe. However, the revolution failed due to a lack of organization and the imamate’s ability to mobilize other tribes, including rivals of the Murad, to support it. Imam Ahmad, the son of Imam Yahya, called on tribes surrounding Sana’a to invade the city. In what became known as the looting of Sana’a, the tribes were given free reign to wreak havoc in the city, as a reward for supporting him during the revolt.[19] Another failed coup attempt in 1959 by sheikhs from the Hashid tribal confederation led to the execution of Sheikh Hussein bin Nasser al-Ahmar, the paramount sheikh of the Hashid.

These revolts concluded with the revolution of September 26, 1962, which deposed Imam Mohammed Al-Badr, the son of Imam Ahmad, who had recently assumed the throne from his deceased father. The revolution was carried out by Yemeni army officers, who were greatly influenced by revolutionary developments across the world, particularly the Free Officers Movement in Egypt. The Egyptian leadership under President Gamal Abdel Nasser would subsequently become the main backers of the newly-established Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) in the civil war (1962-1970) against royalist forces. Yemen’s tribes participated on both sides during the war. Shafei tribes, such as the Murad, which had participated in previous attempts to overthrow the imamate, aligned with the revolutionaries. Sheikh Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar, the leader of the Hashid, also aligned with the new government, partly owing to a personal vendetta against the imamate following the execution of his father.[20] Other tribal factions, such as the Bakil, stood with the royalists, battling the republicans with direct support from Saudi Arabia. Over the course of the civil war, tribes would shift their allegiance between royalists and republicans to attain more money and weapons.[21]

Another prominent feature of the civil war was the relationship between Saudi Arabia and the Yemeni tribes. Historically, this has also undergone different phases and shifts, based on the interests of both parties. The 1930s saw the emerging Saudi state and the Yemeni imamate, backed mainly by Zaidi tribal forces, battle in the tribal regions of present-day Yemen and Saudi Arabia in an attempt to establish dominance in the wake of the Ottoman withdrawal. This conflict eventually ended with the signing of the Treaty of Taif in 1934. Saudi Arabia later supported its former enemy, the Zaid imamate, in the civil war against the republicans, purchasing the loyalty of tribes inside Yemen to fight on its side. After the end of the civil war, Saudi Arabia shifted again and moved to guarantee the loyalty of “tribal republicans,” in particular the Al-Ahmar family of the Hashid confederation. In his memoirs, Sheikh Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar speaks openly about his strong relationship with Saudi Arabia and how the Hashid tribe became an instrument of influence for Saudi Arabia.

This manifested most obviously in the tribes pressuring Yemeni presidents that Saudi Arabia was not satisfied with, such as Abdul Rahman al-Eryani and Ibrahim al-Hamdi.[22] Tribal sheikhs also acquiesced to Saudi Arabia’s request to inaugurate Ali Abdullah Saleh as president after the assassination of his predecessor, Ahmed al-Ghashmi, in 1978.[23] With Saleh assuming power, Saudi Arabia continued to tighten its grip on the loyalties of sheikhs influencing Yemeni politics through the Special Committee. This was first established during the North Yemen Civil War to manage the country’s Yemen file and was under the direct supervision of Saudi prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz until his death in 2010.[24]

In the end, neither side in the civil war could have triumphed without tribal military support, a dynamic that some argue would later upend attempts to build a modern nation in Yemen.

Tribal Influence on War and Peace in North Yemen

Tribes were the most important actors during the North Yemen Civil War, influencing both political and military developments within the republican and royalist camps. Tribal forces were powerful and influential in the new army of the republic; for instance, the ‘Liberation Brigade’ was composed of tribal forces and integrated with the regular army during the first two years of the revolution. Numbering about 5,000 men, these forces fought under the leadership of their respective sheikhs. Other tribes fought in tribal formations, including 1,900 fighters from the Al-Hadda tribe and Hashid forces under the command of Sheikh Al-Ahmar.[25]

The period also saw tribal leaders play a prominent role in peace efforts, employing tribal modes of mediation and customary law in an effort to negotiate an end to the conflict. During the North Yemen Civil War, three national reconciliation conferences were held. The first, the Amran conference, held in September 1963, included both the royal and republican factions and called for defining the Egyptian role in Yemen. The Khamir conference in May 1965 focused on making peace between Yemeni factions. The third, the Taif conference in August 1965, brought together representatives of the republicans and royalist factions for direct talks.[26]

Although they contributed to ending the civil war, these conferences also helped consolidate the influence of the tribes. Among the decisions of the Amran conference was the formation of a popular army to operate alongside the national army, which included official joint forces from tribal units. The popular army included some 28,000 fighters under the command of sheikhs and was intended to replace foreign Egyptian troops that were fighting on behalf of the republican forces.[27] This decision, however, ended up obstructing the establishment of a national army in the modern sense, as tribes kept their fighters apart from the regular army, ensuring that their loyalties were limited to their sheikhs and tribal areas.[28]

On the political side, the tribes exercised influence in the new republican government through the Supreme Council of Tribal Sheikhs, which was formed a month after the 1962 revolution. It was later transformed into the Shura Council as an outcome of the Amran Conference in 1963.[29] The Shura Council was the government’s upper house of parliament, and its mandate included setting the country’s political approach. In other words, the Supreme Council of Tribal Sheikhs integrated with the country’s legislative authority, giving tribal sheikhs major influence over the formulation of the republican draft of the constitution in 1965. This document became the main source for the republic’s formal constitution, announced in 1970. Thus, the constitution ended up being formulated in a way that guaranteed tribal influence over the state.[30]

Modernizers versus Traditionalists

The revolution that toppled Imam Mohammed al-Badr created two currents within the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) that took over the country. The first was a modernizing trend that believed in the necessity of excluding the tribes from a political role and limiting their influence by imposing state control over their regions and establishing a political system apart from tribal identities. This current mainly included progressive forces represented by leftists, nationalists and parts of the military and educated middle class. On the other side, a traditionalist trend argued for maintaining the role of the tribes as an influential, semi-independent force, as they had been in the Mutawakkilite Kingdom. This stance was adopted by right-wing blocs, the Muslim Brotherhood, tribal sheikhs, religious clerics, feudalists, prominent landowners and some army officers.[31] The tribal sheikhs first managed to force the progressive movement to make concessions before eventually sidelining it. This played out as tribes cemented their influence in the legislative authorities, the army and during mediations to end the civil war.

After announcing the establishment of the republic in September 1962, the RCC immediately sought the support of tribal leaders. The Supreme Council for National Defense was established by the RCC in early October 1962, less than a month after the outbreak of the revolution. This body, which included 180 tribal sheikhs, represented “the first official step in establishing contacts between the republic and the tribes.”[32] In April 1963, another ruling body was established by the RCC, the Presidential Council, which also included participation from tribal sheikhs.

During this period, an arrangement was reached between the government and the tribes that allowed sheikhs to collect taxes for the government in areas under their control and to keep 10 percent for themselves. Tribal sheikhs were also granted the right to adjudicate internal disputes. In exchange for their cooperation, the government paid each member of the Supreme Council of Tribal Sheikhs – a body set up by republicans to counter Saudi and royalist influence during the North Yemen Civil War – 850 Yemeni riyals per month[33] (equivalent to roughly $300 when first minted in 1963).[34] This paved the way for sheikhs to formally enter the highest levels of the state apparatus, not as ordinary citizens but as citizens with privileges. Their previous powers were augmented by allowing them to speak with the state on behalf of tribal members and to address tribal members on the state’s behalf.

At the same time, other parties sought to build the new state according to their respective political and ideological visions, with various roles envisaged for the tribes. During the first stage of the revolution, Egyptian support was directed to the republican faction led by Field Marshal Abdullah al-Sallal, the first president of North Yemen, who agreed to involve the tribes in state institutions. Many tribes viewed Egyptian support warily, however, seeing it as a direct intervention by an external power in the internal affairs of Yemen. Competition continued between the modernizers and traditionalists, eventually contributing to the overthrow of President Al-Sallal in November 1967.

Judge Abdelrahman al-Eryani, from the modernizing faction, became president after the overthrow of Al-Sallal. He ruled until 1974, when he, too, was forced to submit his resignation under pressure from traditionalist elements, including Sheikh Abdullah al-Ahmar from the Hashid tribe and Sinan Abu Lahoum from the Bakil tribe. In his memoirs, Abu Lahoum said that the Hashid tribe sent a warning to President Al-Eryani that it would storm Sana’a unless he submitted his resignation.[35] Meanwhile, Sheikh Abdullah al-Ahmar framed the forced resignation request as a result of Al-Eryani refusing to oppose leftist elements within the government. He cited the appointment of Mohsen al-Aini, an affiliate of the Baath party, as prime minister, despite his open hostility to the tribes. Al-Aini had advocated cutting off state financial payments to tribal sheikhs.

After Al-Eryani’s resignation, the presidency returned to the army with Lt. Col. Ibrahim al-Hamdi taking over on June 13, 1974, in what was known as the June Corrective Movement. Al-Hamdi was part of the agreement to overthrow Al-Eryani, according to Sheikh Abu Lahoum’s memoirs, but the new president later turned against the sheikhs and attempted to curtail their influence.

Al-Hamdi’s attempts to take power from the tribes and bolster the strength of the state can be seen in his decision to dissolve the Shura Council, which was headed by Sheikh Abdullah al-Ahmar. Al-Ahmar had submitted his resignation in conjunction with the resignation of President Al-Eryani as part of an agreement between Al-Ahmar and Al-Hamdi that the latter would reinstate the Council and Al-Ahmar as its president. Al-Hamdi did not abide by that agreement, however, and then went a step further by removing tribal leaders from the army leadership. As a result, Sheikh Al-Ahmar labeled Al-Hamdi “dangerous”, describing verbal altercations with the president following the dismissal of prominent sheikhs such as Abu Shawareb and others from the Abu Lahoum family.[36]

Al-Hamdi’s rule did not last long, he was assassinated along with his brother on October 11, 1977. While the perpetrators remain unknown, the killing represented a conclusive victory for the traditionalists, represented by the tribal sheikhs, clerics and parts of the military, over the modernists. In the end, pressure exerted by the traditionalist bloc, of which the tribes formed a major part, succeeded in obstructing the functioning of governments and in overthrowing post-revolution presidents that sought to take on tribal influence.[37]

Tribes and Politics Under the Saleh Regime

When Ali Abdullah Saleh took power in 1978, the relationship between the regime and the tribes stabilized. The new president belonged to the Hashid confederation himself, and adopted a policy of appeasement, granting greater authority and power to sheikhs. Tribal sheikhs were formally integrated into the country’s administrative, legislative and executive structure. This undermined the state and its institutions by sharing power and wealth directly between the regime and the sheikhs.

The deal between the Saleh regime and the tribes also served to distort the customary responsibilities of tribal sheikhs.[38] Under Saleh, sheikhs were transformed into delegates from the state to the tribes. Many tribal leaders joined Saleh’s General People’s Congress (GPC) party and would run for parliament under the GPC banner, mobilizing tribal members to vote for the GPC at elections. Saleh’s regime even revived tribal structures in areas where they had been weak. The political system and the institutions of the state mixed with those of the tribes, taking on the latter’s organizational and hierarchical character. The GPC controlled the political arena amid an absence of political pluralism and the prohibition of other parties. Sheikhs would speak on behalf of the state to their tribes on matters such as basic services, tax collection and conflict resolution. This was a significant change from the past, when sheikhs were seen as representatives of their tribes and made their respective demands on the state. Dr. Adel al-Sharjabi describes this change as “politicizing the role of sheikhs,” which “resulted in transforming authority from a consensual authority to a compulsory authority, and became represented by the power of law and by tribal customs.”[39]

Tribes in Southern Yemen: Co-option and Exclusion

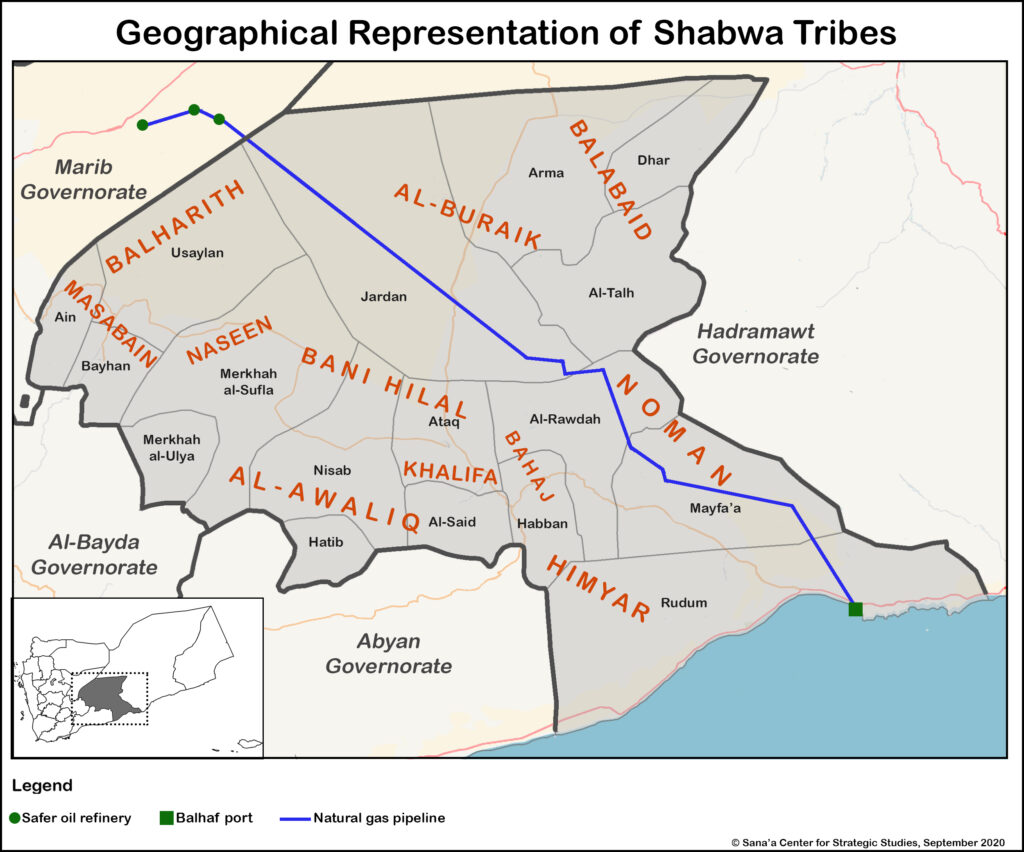

The southern regions of Yemen are generally considered less “tribal” than the northern regions,[40] but this does not apply to all geographical areas in the south. There are parts where tribal structures are strongly present, such as Shabwa and Hadramawt. Other areas have experienced a weakening in tribal influence over the years, with this often attributed to the British occupation of southern Yemen beginning in 1839. This led to the establishment of civil governance in Aden, which influenced the surrounding areas. Tribal influence was subsequently curtailed further as a deliberate policy during the period of rule by the National Front and Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) in South Yemen from the end of the 1960s until unification in 1990.

Both before and during the British occupation, southern Yemen was made up of scattered sheikhdoms, emirates and small sultanates that ruled specific geographical areas and interacted with neighboring entities through alliance or conflict. Among the most notable of these were the Fadhli Sultanate in Abyan, the Abdali Sultanate of Aden and Lahj, the sheikhdoms of Upper and Lower Yafea, the sultanates of Upper and Lower Al-Awaliq in Shabwa and the tribes of Al-Sabiha in Lahj. These tribal-based entities were similar to their counterparts in the north, in terms of having dominion over their tribal territory, ruling by customary law and engaging in intertribal conflict. For example, the Sultanate of Al-Fadhli engaged in multiple confrontations with Al-Awaliq,[41] while the sheikhdoms of Yafea battled imamate forces in northern regions of southern Yemen before British colonization.[42]

After the British occupied Aden in 1839, confrontations erupted between British forces and local tribes.[43] The British, seeking to avoid confrontation, adopted a policy of signing protection agreements with existing sheikhdoms. The first protection agreement was struck on June 18, 1839, with the Abdali Sultanate, which was ruling Aden at the time. The Sultanate agreed that the tribes under its rule would not attack British interests and would protect the transportation routes in its territory. In return, the British government paid the Sultanate an annual fee. British forces then proceeded to secure similar protection agreements with the other sultanates, chiefdoms and feudal principalities, with the total number of agreements reaching 90 by 1954.

The British let these entities maintain a large degree of autonomy, ostensibly only intervening to settle disputes. This changed in 1937, however, as the British moved to exert more direct authority. This followed a British royal decree ordering that the sultanates and sheikhdoms of southern Yemen be transformed into eastern and western protectorates, and Aden established as a colony of the British crown. From this point, local rulers were obliged to accept and carry out the “advice” of British authorities based in Aden. This state of affairs continued until the revolution in 1967, which led to the British withdrawal from southern Yemen and the establishment of the People’s Democratic Republic of South Yemen.[44]

While the British had set the basis for state institutions and civil society in Aden since the beginning of the 20th century, the sultanates that governed the neighboring areas of Abyan, Lahj and Shabwa maintained tribal characteristics despite the influence of the Aden colony. The leftist nationalist revolutionaries that seized power in 1967 however, had a clear anti-tribal stance, describing them as feudal and reactionary powers. Rather than making concessions that would grant tribal forces and sultanates a chance to integrate their traditional form of rule into the newly-established leftist state, the revolutionary movements that seized power adopted strict measures to crush tribal and feudal blocs. “Tribalism was severely condemned and was perceived as synonymous with feudalism,” researcher Elham M. Manea writes. “As a result, village headmen, who owned no more than anyone else, were murdered by the state as ‘feudal landlords’.”[45]

Tribal components were systematically integrated as the YSP sought to eliminate class differences, encouraged people to give up their tribal titles and worked to remove tribal loyalties in favor of party loyalty. As part of the Agrarian Reform Law adopted in 1970, the state confiscated all of the agricultural lands of former sultans and feudalists and their families without compensation.[46]

Tribes and Politics from Unification to the 2011 Revolution

The unification of Yemen in May 1990 witnessed important changes to the nature of the political system. Neither North or South Yemen had experienced real political pluralism during their respective histories, and there are notable differences in the nature of their societies.

In South Yemen, the secular socialist system ended traditionalist power by forcibly incorporating societal components into a one-party system. In North Yemen, traditional powers, most notably tribes, imposed control in a profiteering and integrated relationship with Saleh’s regime after 1978. This relationship was based on a confluence of interests and the patronage that northern sheikhs would receive from the state in exchange for loyalty to the regime and the provision of tribal manpower for military purposes. This would continue in the unified Republic of Yemen.

With encouragement from Saleh, in September 1990 the paramount sheikh of the Hashid tribal confederation, Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar, led the founding of the Yemeni Congregation for Reform, more commonly known as the Islah party. A number of the tribal sheikhs who were members of the GPC, which was led by Saleh himself, moved to this new party, which brought together Muslim Brotherhood Islamists, Salafist groups and tribal confederations, most notably the Hashid. This movement of tribal leaders from the GPC to the newly-established Islah party was not the result of political pluralism so much as a ploy to distribute northern forces against the YSP, the primary political representative of the former South Yemen.[47]

The alliance between Islah and the GPC against the YSP then escalated into civil war in 1994, after the YSP demanded an end to unification and a return to two separate states. Here again, as during the North Yemen Civil War, tribes played a major role, as Saleh employed a reservoir of armed northern tribesmen to invade the south and impose unity by force. As a reward, after the victory of the northern forces Saleh named Al-Ahmar speaker of parliament, despite the fact that the GPC held the most seats of any party in the legislature.

Following the 1994 civil war and the defeat of the YSP, Saleh was unrivaled in authority and able to further cement his support among Yemen’s tribes. A 2010 study by researcher Adel al-Sharjabi found 17 of 22 governors came from tribal backgrounds.[48] In 1995, the president issued a decree that paved the way for him to redistribute both state lands and private real estate in the south, which was then channeled mainly to family members and sheikhs that had participated in the 1994 civil war.[49] This followed a familiar script, as Saleh was himself a member of the Hashid, and had made the distribution of key military and government positions to members of his family and tribe a hallmark of his rule. The president also used public funds to finance the Authority of Tribal Affairs Fund, which was established in the 1980s to pay monthly salaries to tribal sheikhs without any structured or legal mandate.[50] This authority was expanded post-unification to include southern tribes, with the funds disbursed to various sheikhs and neighborhood aqils (leaders) depending on the scope of their influence.

At the national level, tribal structures were revitalized, even in areas where they were largely absent previously. Sheikh and aqil positions were established in cities like Aden, where citizens had to request services directly from these figures instead of the state.[51] Sheikhs were also given responsibility for issues such as law enforcement and gathering lists of poor and needy individuals in their areas, which led to abuses. Sheikhs were accused of operating private prisons outside of the scope of the state, with those accused including members of parliament Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar and Yasser al-Awadi, a tribal sheikh from Al-Bayda.[52] Another prominent example was Mohammad Ahmed Mansour, a leading GPC figure and a member of the Shura Council. He was accused of running a private prison, imposing a feudal system in areas under his control and collecting unlawful taxes.[53] Despite the fact that the case received wide coverage in the media, the sheikh was not held accountable.

Under Saleh’s rule, the state gradually turned into a tribe, while the tribe turned into a state.[54] The military, the political system and the administrative and financial system became based on the hierarchy of tribal structures, with these concentrated in the hands of the tribal sheikhs surrounding the president and his family. These positions have been passed down from generation to generation in electoral districts.

The tribes also have heavy weapons, in addition to a staggering number of small arms. These weapons and fighters have been used as an irregular fighting force fighting alongside the state in Saleh’s wars against the Houthi movement between 2004 and 2010.[55] The judiciary has also been marginalized, with tribal mediation taking its place. Even in the capital, it became normal to see tribal gatherings in which a bull was slaughtered next to a police station as a peace offering to settle a conflict. This was done with the encouragement of the president, who personally acted as a tribal sheikh and managed the country in this manner.

This dynamic – and the ways in which the tribes have acted as an alternative to state power and statutory laws – will be discussed in more detail in the next section of this paper.

Part II: Tribal Laws and Alternatives to State Rule

Tribal Codes at the Onset of the Current War

The war that began in 2014 with the armed Houthi movement’s takeover of Sana’a has hindered the state’s ability to impose the rule of law, but alternative, customary law has always been present in Yemen. As discussed in the first part of this research, Yemeni tribes have maintained their cultural heritage and continued to practice their customs despite the presence of a central state, recurrent war, turbulent politics and changes of government.

In northern areas, citizens have resorted to customary law during all phases of the state’s rule. Many prefer customary law, because they feel it has resolved their problems and organized matters of livelihood more efficiently than the state’s legal and judicial system.

During his rule from 1978-2012, President Ali Abdullah Saleh worked to revive tribal structures. Combined with the notoriety of the state legal system, this led to the adoption of traditional and tribal customs even in areas where there was no recent history of their use.[56] The diverse social hierarchies of the tribes have proved highly durable in many parts of the country. Yet, despite the regional diversity in tribal customs there are similarities in terms of tribal customary laws and the extent of their implementation across Yemen.

Customary laws were created to organize military affairs between tribes or tribal confederations, as well as everyday economic, legal and social affairs for individuals. This part of the analysis will discuss tribal customs and traditions specifically in terms of how they create and resolve conflicts and the extent of these traditions’ influence on the use of statutory laws.

In an interview in October 2020, Sheikh Hussein al-Aji al-Awwadi, the former governor of Al-Jawf governorate and a member of a family of sheikhs from the well-known Al-Awwad tribe, defined tribal customs as, “A system to manage life-related affairs that was produced by the evolution of tribal societies throughout history. These tribal societies, where the state has always been absent, needed to develop legal methods that [act as] deterrents and that organize affairs among people.”[57]

These customs and traditions are passed down orally, making it possible to add to and adjust them as necessary. The traditions are defined by individuals, yet derive their legitimacy from a collective consensus. According to one source[58] from Khawlan district, east of Sana’a, customary rules are derived from the same rules that were present in the old Yemeni kingdoms, such as the Sabean Kingdom that ruled central Yemen between 1200 BCE and 275 CE. These rules were renewed in 1838 and approved by Yemen’s then ruler, Imam al-Nasser. They have become a cultural contract that has allowed society to self-regulate, where each individual knows his rights, duties and the consequences of any wrongful acts.[59]

Another source, in Dhamar governorate, explained that, “Customary rules in terms of penalties differed between one tribe and another. However, it was agreed to unify these penalties and punishments during a meeting that included tribal sheikhs and religious scholars in 1838.”

The source drew on handwritten documents from that meeting in explaining his views. “Participants agreed on unifying customary rules,” he said, “unifying the names and definitions of wrongful acts, as well as principal and subsidiary penalties.”[60]

War and Peace

Tribal customs have been used to resolve disputes ranging from the dumping of trash to fierce battles over borders, and to issues over resources within tribes. The tribes have developed a legal system that aims, first and foremost, to contain disputes and peacefully resolve them. There is a clear contradiction between this, however, and tribal traditions regarding war and violence as a means of acquiring property. Within this context, researchers Raiman al-Hamdani and Gabrielle Stowe developed a theory that tribal violence itself created the motivation to resort to peaceful methods, particularly mediation and arbitration, to resolve disputes.[61]

Resources that create conflict include the distribution and management of privately owned grazing lands, communal lands and water resources. Disputes have also erupted over development projects and matters related to oil and gas companies. These are mostly present in tribal areas like Marib, Shabwa and Al-Jawf, and are often over building and services contracts.[62] Tribes compete to sign contracts with these companies, with some reporting that their operations have been suspended due to violence from tribes targeting company employees and facilities in these governorates.[63]

A Tribe that Resembles a State and a State that Resembles a Tribe

Even after the establishment of the state, tribal structures have continued to provide a social system through which many Yemenis organize their daily affairs, resolve their conflicts and remain a secure society. A “chicken or the egg” question applies here: has this social system and the influence of tribal customs weakened the state, or is a weak, corrupt state the reason tribes have remained strong and influential?

Sheikh al-Awwadi argued that the continued influence of tribal customs was as a result of a weak and often unjust state. He used the example of President Saleh’s regime lifting fuel subsidies in 2004. People took to the streets demanding a retraction of the decision, but Saleh did not back down until tribes from Marib and Al-Jawf placed their support behind the demonstrators.

Al-Awwadi said that the tribes have not always been against the state and its institutions. On the contrary, “Tribes long for the presence of a strong state that maintains order and provides security.” He gave the example of Ibrahim al-Hamdi’s presidency, from 1974 to 1977.[64] “Thanks to his political speeches, which opposed the sheikhs and their authorities, he managed to convince people and their sheikhs to stand by the state,” Al-Awwadi recalled.

The counterargument is that the state co-opted tribal structures to increase its authority. In other words, the political system “imported” the sheikhs, along with their traditional qualities, in their capacity as representatives of their tribes, in order to support the system. This was not intended to integrate them in a way that preserved their representative character, but primarily to protect state authority and keep the tribes and their sheikhs under control.

During the Saleh regime, the sheikhs enjoyed great influence within the regime itself. But by being removed from their tribal areas of influence and brought to Sana’a to be close to the regime, their independence was further compromised.[65] The huge sums of money that sheikhs received from the Saudi Special Committee (the entity in Riyadh responsible for Saudi Arabia’s Yemen policy) helped ensure their loyalty went in one direction: toward power and the ruling regime. This, in turn, led to the imposition of traditional tribal methods on the system itself, and their separation in one way or another from other social components.

“The tribal system that’s supported by the authority largely contributed to disrupting the balance of relations of social components in favor of the tribe at the expense of other social components,” according to academic Hani al-Maghles,[66] leading to rampant corruption and favoritism in the state’s organizational structures. This turned the project of the state into a range of personal projects seeking profit and wealth. This overlapping and integration created a “state that resembles the tribe and a tribe that resembles the state,”.[67]

“Paper Tiger” Sheikhs: How the State has Weakened Tribal Structures

Sheikhs’ involvement in politics resulted in a distortion of the traditional role tribes had previously played for their members. Sheikh Al-Awwadi summed this up: “The sheikhs who [became more influential] amid the presence of the state are loyal to the authority and not to the [tribe’s members], and the connection between tribes and their sheikhs is no longer the same.” One source described tribal sheikhs after 1962 as “paper sheikhs”, adding that this kind of sheikh was “intentionally” created to be subordinate to the state and turn “the tribe from being the base of social structure to a tool that demolished it.” He blamed Saudi funding of tribal leaders for driving this change.[68]

Public positions and occupations were distributed among families that were influential and close to Saleh and who mostly came from the same tribal area. Yet, while Saleh elevated the power of local sheikhs, this did not benefit members of their tribes at large. This is clear from the high poverty rates in governorates which large tribes belong to. For example, the governorate of Amran, home of the sons of Sheikh Abdullah al-Ahmar, head of the Hashid confederation, one of the most powerful and influential sheikhs in modern Yemen until his death in 2007, is still one of the country’s poorest governorates.[69]

After unification in 1990, the regime intentionally weakened the state and worked to support tribal identity and increase its influence.[70] For example, in areas where these tribal structures were less dominant, the state created public roles and positions, such as the aqil al-hara — a community elder in a neighborhood. The state granted these positions wide jurisdiction, ranging from law enforcement to determining who deserved financial or social support among the poor.[71] Criminal procedural law gave local authority representatives – such as sheikhs and aqils in neighborhoods and villages – law enforcement powers in tribal areas. The criminal procedural law – Criminal Law No. 13, issued in 1994 – gave the sheikhs and neighborhood chiefs in cities and villages the power of “judicial control officer”, in addition to other civil duties. They were also tasked with connecting citizens to the official authorities in cases of need. This role was given to them as many tribal settlements are small, far from major centers, and in terrain where access can be very difficult. Maintaining regular state institutions in such places was impossible, with a devolution of authority to the sheikhs and neighborhood chiefs the result.[72]

Aqils were also given the right to identify those who were not listed on electoral rolls.[73] Therefore, even in cities where it might be expected that statutory law would be respected and implemented in its modern form, it was traditional methods and tools that prevailed. Responsibility for services, development projects and citizens’ complaints were transferred to the same “traditional” social representatives, and not to state institutions. This happened in agreement with the governing system that represented tribes and went all the way to the top: Saleh himself frequently resorted to customary laws and tribal mediation to resolve national problems or other problems related to security.[74] An example of this followed the killing of the deputy governor of Marib in a drone strike in 2010. Saleh requested the intervention of a tribal mediation committee to contain an imminent clash between government forces and local tribes.[75]

Protection of Criminals

The traditional orientation of a tribe creates group solidarity via the tribe’s symbols and influences. This solidarity is often referred to as asabiyya and is a major characteristic of tribal communities, as well as the most prominent dynamic of tribal structure, according to scholar Hisham al-Sharabi.[76] Asabiyya sometimes provides protection via the indirect intervention of tribal leaders. More directly, tribal members might exert pressure on state authorities to protect or release law-breakers who belong to their tribe, or prevent the authorities from holding fellow tribal members accountable.

These law-breakers may have committed serious crimes, such as setting up roadblocks, kidnapping or murder. One example is the abduction of foreigners. In 1999, for instance, tribesmen from the Bani Jabr tribe kidnapped three US citizens in Marib governorate, just east of Sana’a. The kidnappers demanded the release of 25 fellow tribesmen, who had been detained by interior ministry police in connection with the blowing up of an oil pipeline a few days earlier. The US citizens were subsequently released.[77]

The incident also underscores how tribal traditions include the possession of arms on a large scale, with weapons a part of tribal appearance and social status.[78] The tribe and the state thus share the tools of violence, with tribes using these to exercise power – sometimes against the state. Another example of this occurred in March 2011, when tribesmen blew up an important oil pipeline linking Marib, in the center of the country, to export facilities at Ras Issa port on the Red Sea. The explosion suspended a significant source of government revenues and harmed local fuel supplies, with Saleh and his supporters accusing tribal members of carrying out the attack.[79]

Asabiyya has been an obstacle to implementing laws, which were supposed to replace tribal customs that do not harmonize with the nature of the violations committed. Asabiyya also contradicts the law, allowing tribal influence to impose itself on standards of justice and law enforcement. This concept is directly at odds with state authority. As researcher Abdulghani al-Iryani puts it: “[Asabiyya] prioritizes individuals at the expense [of the sense] of belonging to the country. What primarily embodies identity is the tribe and not the state. If an individual [belongs to the] Hashid, he’s first and foremost a Hashidi and then a Yemeni, and not the opposite. If there is a contradiction between the interest of the tribe and the general interest, tribal members will select what is in the interest of the tribe and what serves its interests before other tribes, according to tribal customs.”[80]

Positive Jurisprudence?

In contrast, some believe that tribal traditions are not as bad as they have sometimes been perceived. Supporters of such a view argue that despite historical conflict, the tribes have maintained their presence as organized and united entities thanks to the tribal rules and customs that have governed their relations.

According to anthropologist Najwa Adra, these customs cover all behavior Yemenis define as social, including rules of hospitality and greeting. They are therefore as much a code of conduct as a set of legal directives.[81] This code of conduct and legal guidance includes concepts such as honor, dignity, sympathy, protecting vulnerable individuals, pardoning others and accepting reconciliation.

Unlike the official court system, a dispute in customary law is not considered resolved unless both parties agree on the proposed solution. Researcher Nadwa al-Dawsari, an expert in the affairs of Yemeni tribes, describes customary law as, “based on consensus-building and maintaining relationships. Key to tribal traditions are transparency, accountability, solidarity, collective responsibility, the protection of public interests and the weak. Dialogue and the culture of apology are embedded in the practice and rituals of tribal customary law.”[82]

Yemenis have often had more confidence in tribal customs than the public court system, which has been characterized by corruption and favoritism and marred by lengthy procedures.[83] Litigation in state courts is viewed as a painful and costly process, while tribal customs represent a more trusted, easily accessible alternative. In some instances, there may be no other method of resolving disputes available. It has become normal for many citizens to resort to tribal processes rather than the courts.

The binding power of customary justice has long contributed to resolving and de-escalating conflicts between families and tribes. Researcher Nadwa Al-Dosari indicated in her study that a local study in 2006 for German Development Corporation (GIZ) suggested that 90% of local conflicts were resolved or prevented through tribal customs.[84] Tribal arbitration is usually undertaken by tribal elders or other individuals and is often characterized by flexibility and a sense of “humanity”. Intissar al-Qadi, from the Early Warning Center for Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding (EWCCRP)[85] in Marib, told the author in October 2020 that the difference between regular judicial laws and customary laws lies in penalties, where the latter does not stipulate time in prison, but imposes financial penalties to which both parties agree.[86]

Drivers – or Parties – to Conflict

At the national level, tribes have been a party to every conflict in modern Yemeni history. Indeed, tribesmen have been used as fighters by conflicting parties since the time of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom and its wars against local opposition and the British occupation.

The provisions of tribal customs are strict in cases of internal conflict between tribes, with clear and agreed upon caveats enforcing nonaggression and respect for the property of other tribes. This does not mean that there are no inter-tribal conflicts over leadership. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, for example, there was a bloody conflict over the leadership of the Hamdan tribe.[87]

Tribes were again used during the North Yemen Civil War between republicans and royalists, as well as during the 1994 Civil War. Tribesmen were deployed on a wider scale during Saleh’s wars against the Houthi movement, known as the Sa’ada Wars (2004-2010). One example of this was in October 2010, when, at a meeting of Hashid tribes in Khamer, Amran, Sheikh Hussein al-Ahmar urged them to eradicate Houthi forces. The tribes then pledged to kill those joining the Houthi movement.[88]

President Saleh’s use of mercenaries from the Hashid tribe to fight in the ranks of the army during the wars against the Houthis between 2004 and 2010 led to resentment among the tribes of Sa’ada. This spurred many to join the ranks of the Houthis to retaliate against the state and to gain revenge for violations committed by combatants from the Hashid tribe against their tribes, within their lands, and against their societies.[89]

The tribes are currently being used in the ongoing war as proxy combatants for various parties,[90] including by the Houthi movement – a dynamic that will be discussed at length in the third part of this analysis.

Corruption and the State

Some tribal leaders gained a bad reputation under the Saleh regime during the decades preceding the current conflict, due to the wide-reaching patronage networks that these sheikhs represented. Even during the war, sheikhs have changed their loyalties based on personal interests.[91]

For many years, sheikhs that were influential at the national level received large payments from Saudi Arabia in exchange for services that were not necessarily beneficial to their communities or to the Yemeni state.[92] They were described by one sheikh as, “The sheikhs of the Special Committee, who sold the country, destroying it and destroying the lives of future generations.”[93]

In addition, there were funds that were allocated to these sheikhs from the Tribal Authority Fund. This was administered by the Tribal Affairs Department – part of the Ministry of Interior – and was used by Saleh from the 1980s onwards to distribute monthly funds to dozens of sheikhs via branches based in the different governorates. These were public funds ultimately coming from the state budget, yet there was no law regulating the department’s activities.

This funding created a class of extremely wealthy individuals, while very few tribal members received any of the wealth from their sheikhs, despite a popular perception outside the tribes that all tribal members had become wealthy. Indeed, most tribes lacked development projects and basic services, just like most Yemenis.[94]

Tribal members responded to corrupt state authorities and the networks of sheikhs in control of public funds by using traditional tribal methods. From the beginning of the 1990s, a number of tribes resorted to kidnapping – and at times killing – tourists. A group of nine foreigners was kidnapped in the governorate of Sa’ada in northern Yemen in 2009. Three of the women, two Germans and one South Korean, were later found dead near the city of Sa’ada.[95]

Other actions have included sabotaging pipelines and power lines and putting roadblocks on highways. These are all attempts to pressure the state into meeting the demands of a tribe, or particular demands of the perpetrators themselves. These have ranged from ransom payments to the implementation of development projects, as well as demands for the release of detainees in the state’s custody, or compensation for lands that the state has used or taken.

“In northern areas, especially the areas to the north of Sana’a,” Dr. Adel al-Sharjabi writes, “tribal structures control social relationships, and tribal loyalty creates a form of political awareness that can only be seen through collective demands, which are based on direct material interests. This normalizes rent-seeking behaviors, with the state being viewed as an organ to distribute rents. If the state stops these grants, the popular response among the tribes is rebellion through cutting off services or kidnapping foreigners.”[96]

At the same time, the political system that the tribes have come to know is one in which “political influence becomes a means for unaccountable power and wealth accumulation,” according to researcher Nadwa al-Dawsari.[97] As a result, elections have sometimes been accompanied by armed violence and intimidation in tribal areas, which has led to death and injury. In Rada’a, in Al-Bayda governorate, clashes that started as competition between nominees for a local council in 2006 led to a tribal conflict during which at least 47 people were killed.[98] Al-Dawsari also cites reports of election-related violence occurring in tribal areas in Al-Jawf, Marib, Amran, Dhamar and other governorates.

Tribes as Mediators and Resolvers of Conflict

Despite the instrumentalization of tribal traditions in fueling conflict, these traditions have also contributed to its resolution at both the local and national levels.

Any individual – man or woman – can offer to mediate and resolve a conflict. This is not considered unusual[99] and is actually welcomed and preferred in tribal societies. These interventions to end conflicts are based on a sense of responsibility toward society, and in line with the role that tribal members have historically played.

With tribal leaders becoming increasingly involved in the political arena and state affairs, their traditional tools have been used to resolve conflicts, whether political or military in nature. In December 2011, a tribal mediation committee led by one of the Hashid sheikhs was able to implement a ceasefire between Salafis and Houthi forces in Dammaj after deadly clashes.[100] Mediators returned to this volatile area a number of times, with the fighting only ceasing in 2014.

In cases where tribesmen themselves have been involved in acts of sabotage or terrorism, tribal mediation committees have been formed between the state and the saboteurs. As an example, in December 2011, tribal mediation efforts in the Marib governorate were able to secure the release of four foreigners. Tribesmen in the Sirwah district of the Marib governorate announced that they had kidnapped the foreigners to pressure the government into compensating them for damage done to their farms by the Yemeni army, three years prior.[101] In 2018, tribal mediation succeeded in ending a series of revenge killings between tribes in Marib dating back to 1974. The sheikhs of the largest tribes in the region participated.[102]

Even when the intervention of sheikhs has not been successful, their efforts have nonetheless shown their willingness to challenge far stronger opponents. A 2019 tribal mediation was undertaken to resolve a dispute between fighters supported by the UAE and the tribes of Shabwa, after the killing of nine tribesmen by forces known as the “Shabwani Elite”. To date, repeated rounds of mediation have not settled the dispute, which remains a sensitive issue, but the tribes have continued to press their claims in the face of powerful Emirati interests.[103]

Laila al-Thawr, a human rights, political and peacebuilding activist since 2011, has been a key mediator in Yemeni prisoner exchanges. She has directly contributed to the release of more than 600 captives held by different parties during the current conflict.[104] She has also assisted in the resolution of several long-standing disputes using tribal mediation methods.

One such dispute, one of the most well-known cases in Yemen, required extensive mediation. This incident occurred between the Mutahar family, a family of merchants from Taiz, and the Hazal family, a family of sheikhs from Marib. The two quarreled over land and the dispute led to a long-running feud. In 2014, a court ruled against the Al-Hadhal family, which rejected the court’s decision, kidnapping two of the Al-Mutahar’s children to try and force a more favorable resolution of the land dispute. In 2018, Al-Thawr became involved in the mediation and succeeded in getting the two children released. She then helped resolve the land dispute in March 2019.[105]

The most prominent achievement of tribal mediation in wartime has been the exchange of prisoners. In contrast to official channels, tribal mediation has succeeded in brokering deals that have led to the exchange of thousands of captives between the Houthis and the government and local tribes. Tribal leaders have also successfully negotiated short ceasefires and safe passage for civilians, as well as the recovery of the dead from the frontlines.[106]

Women in the Tribal System

Yemen has long been near the bottom rank in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index. After years of war, that situation has only worsened, according to a number of studies.[107] Between war, domestic violence, repression of freedom, early marriage,[108] a lack of education[109] and healthcare, the absence of basic services, hunger, illness and a lack of safety in the street and at the workplace, Yemeni women are struggling in a conservative and patriarchal society that upholds strict social traditions.

Those social customs and traditions, mixed with conservative religious values, have also limited women’s work opportunities and restricted their participation and level of achievement in society, while giving full authority to their male guardians.

In 2009, Amnesty International stated that “Women in Yemen face systemic discrimination and endemic violence, with devastating consequences for their lives. Their rights are routinely violated because Yemeni laws, as well as tribal and customary practices, treat them as second-class citizens.”[110] This is despite the fact that the Yemeni constitution protects the basic rights of women.[111]

Social traditions and tribal customs relating to women are not the same everywhere in Yemen. Female tribal actors working in mediation and training in conflict resolution, using traditional mediation mechanisms, told the author in January 2021 that the number of regions that still applied traditional tribal customs was declining daily.[112] These women said that areas with tribal societies that had lost their original tribal identities were the worst places for women to be. In such places, there were no traditions deterring harassment of women, with verbal and physical harassment rates rising accordingly, both in the streets and public places as well as in the home.

Al-Thawr defines tribal customs as all of the customs and traditions that are agreed upon in society, saying that tribal adherence to customs is positive. She believes that women within the tribal structure have “gotten an opportunity and have been treated better than the laws implemented by the modern state in Yemen.” An example she gives is of how women in tribal societies have a “special” position, and that their customs guarantee women respect and preferential treatment, prohibiting assaults on women in any form. They also prohibit attacking a man who has a woman with him, even if he is a killer, as this would be considered a “shameful” action in the tribal code. She also adds that a nakaf — a tribal declaration of emergency — called for by a woman, or called for on behalf of a woman, is considered more powerful and binding than a nakaf called by or for a man. Al-Thawr added that women can become involved in efforts to manage conflicts, although this is difficult because men in power refuse to acknowledge women’s roles in successful efforts and attempt to take credit for their achievements.

Al-Qadi explained that tribal customs are in line with Sharia law in meeting people’s needs and resolving conflict, and differ from state jurisprudence in the penalties they impose. Penalties from the judiciary rely on the authority of the state, while those in tribal customs rely on popular traditions.[113]

Al-Qadi agreed with Al-Thawr in that tribal customs were applicable to all cases in which the law was also applicable, adding that they are also quicker and more accessible than the justice system. Both emphasized the special treatment granted by tribal customs. Women cannot be attacked during disputes, whether between individuals, tribes or whole regions. Women are protected during wars, and Al-Qadi said that even in “recent times,” if a group of combatants are surrounded, women can escort them out, as they cannot be attacked while under a woman’s protection.[114]

Al-Qadi said that women were still respected while traveling, despite the fact that tribal traditions have been destabilized recently. Anyone who assaults a woman is considered to have committed a very shameful act that is not accepted by society. She added that in tribal custom, the penalty for assaulting a woman is harsher than the penalty for assaulting a man in terms of fines.[115]

As proof of the importance and influence of women in tribal customs, Al-Qadi noted that if one of the parties in a dispute was not moving toward a resolution, it was customary for a mediator to take their daughter with them to the party that had rejected a proposed solution. This is because a woman being involved in resolving a problem may have more impact than scores of men, as a party that rejects a solution in the presence of a woman is considered an “outcast among all of the tribes”. The daughter’s presence alongside her father often leads to the party that had not accepted the solution giving in and accepting a compromise.

Yet tribal structures also place limitations on women. Al-Qadi spoke about the challenges that female activists face in their tribal communities. She believes that the biggest challenge is whether a woman’s family will support and accept her work and empower her to take on a mediating role. Women cannot participate in resolving disputes at a higher level if their fathers, mothers or brothers do not give them permission. Al-Qadi added that a family’s refusal to do this might be intended as a way of protecting the woman, as the family fears she would be subject to harm or humiliation. Al-Qadi said that this justification was used if a woman had already been attacked, even if only verbally, as this too is considered a crime in tribal customs. An attack on a woman might then cause an even larger problem than the one the woman was trying to resolve.

Al-Qadi said some women were now trying to expand the scope of their participation in conflict resolution to areas outside their own tribes. She added, however, that according to tribal customs in Marib, it was still not acceptable for a woman to offer her mediation to a tribe other than her own, unless she had been present at the time of the incident requiring resolution. Al-Qadi said that this practice could change over time, as women have started to operate more widely in a personal capacity. She said that she had participated in resolving conflicts between different tribes, but that these efforts had not been made public and had occurred through direct communication with the parties involved.

Despite their differences, local communities in Yemen comply with customs and traditions. In some cases, these tribal customs elevate the status of women and protect them. But tribal customs also promote the idea that women are weak. It is widely seen as being in agreement with religion – and laws based on customs and religion – that women should rely on the protection and the presence of a man, whether he is their guardian or at the top of the tribal structure.[116] Women lose the advantage of protection or respect if the men in the family are absent or are not supporting the women, or if women decide to work outside of the limitations set for them. This view is shared by researcher Najwa Adra, who wrote in a 2016 study that, “Since tribal law does not regulate behavior within the immediate family, women’s safety nets protect them only if their fathers and brothers are decent. Moreover, tribal ideology is male-oriented. Men are charged with representing their tribe in public venues, and tribal leadership is overwhelmingly male.”[117]

There are women who have contributed and are contributing to the leadership of their communities through tribal entities, but they are very few and far between. These women are breaking new and difficult ground, going against entrenched beliefs and a male majority. This “male culture” has limited the roles of women, under the pretext of protection and “shame”, curbing their interactions with men. This has led to many of the problems that Yemeni women face today, in getting education, opportunities in the job market, equality between the genders and other basic rights.[118]

States that are not States, and Sheikhs that are not Sheikhs

In recent years, the power of some sheikhs has grown within a corrupt state that has not imposed the rule of law. This relationship has hindered both parties: the state does not function like a state, while the sheikhs no longer represent the members of their tribes. Despite the immense wealth that some of these sheikhs enjoy, their tribes and tribesmen have not benefited.

The next and last part of this analysis will discuss how sheikhs and tribal mechanisms have played a central role in the current war.

Part III: Tribes and the Current Conflict

Background to the Current Conflict

March 26, 2015 is often cited as the date the current war in Yemen began. In fact, this date only marks the start of the Arab Coalition’s official intervention in the war – or wars – already happening in the country. In reality, there has been a continuous series of conflicts in Yemen, stretching back over decades, in which individuals and groups have allied together according to their perceived political interests. The current war is just the most recent in this series of confrontations – conflicts in which Yemen’s tribes have played an important role.

Following the September 1962 revolution, the civil war between the republicans and the royalists in North Yemen ended in 1970 with a republican victory, along with a consensus between major regional players toward both sides in the conflict. At the same time, leftist revolutionaries in South Yemen were preparing to establish a socialist state after the British withdrawal in 1967.

Both countries suffered from internal conflicts. In the North, strong sectoral and tribal identities emerged. These identities represented intertwining centers of power, which sometimes competed, and at others allied together. Presidents in North Yemen were toppled one after the other, with Part I of this study showing how tribal affiliations played a major role in these changes until Ali Abdullah Saleh assumed power in 1978. Tribal support for Saleh was subsequently facilitated through a partnership financially sponsored by Riyadh.

In South Yemen, clear ideological differences existed among leaders of the ruling Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP). The disputes also related to factionalism between different southern governorates and a civil war erupted between different YSP factions in January 1986. This regionalist, rather than tribal, dispute resulted in a bloody divide between leaders hailing from Abyan and Shabwa and those from Al-Dhalea and Lahj. Many figures from the defeated Abyan-Shabwa faction fled to the North in the aftermath of the civil war, and later played a decisive role in the 1994 war.

The year 1990 marked the unification of North Yemen and South Yemen. This happened at a time when the South was exhausted from the 1986 civil war and in a difficult economic situation amid the breakup of its primary foreign backer, the Soviet Union. Governance of the unified Yemen Arab Republic settled in the North, after leftist factions – known as the National Front, which had resisted the regime in central areas – were crushed.

Relations between the northern and southern leaderships quickly deteriorated, with the latter complaining of being excluded from decision-making posts and accusing the former of assassinating YSP leaders. These tensions escalated into civil war in 1994 following an attempt by southern leaders to secede. The northern army, supported by northern tribal militias and southern military figures from the losing Abyan-Shabwa side of the 1986 conflict, succeeded in crushing this attempt and keeping the country unified.[119]

After the 1994 conflict, Saleh and his main backers from the northern tribal elite were unrivaled in power. The General People’s Congress (GPC) party, headed by Saleh, dominated parliament with a sweeping majority, while Saleh also controlled the country’s military and economic power.

The other main political party at the time, was the religious tribal Islah party. Despite its opposition status, however, Islah continued to support Saleh due to an intertwining network of interests. Many who joined Islah had originally belonged to the GPC, or were supporters of the northern regime it represented. The leading members of the two parties also belonged to the same well-established tribal, business and personal networks that formed the Yemeni elite.[120] No other parties were able to exert influence at the political and legislative level due to their small size or and systematic weakening after the 1994 war.

However, other groups emerged and began to challenge Saleh’s government, most notably what would become the armed Houthi movement. Supporters of the Believing Youth Forum, a movement founded by Hussein al-Houthi in 1992, initially sought to redress perceived injustices against Zaidis in Sa’ada governorate.[121] The group, which eventually crystallized as Ansar Allah, the Houthi movement, became more militant after the US-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003, before finally taking up arms in 2004.[122] Confrontations between Al-Houthi’s followers and the army ended with his killing, along with a number of his supporters, in September 2004. Five more rounds of conflict followed until 2010, in which tribal fighters participated on both sides.

Southern Yemen also witnessed the emergence of an opposition movement, voicing grievances felt by the southerners since unification. The demands of Al-Hirak (the movement) developed over time, ranging from the reinstatement of soldiers discharged from the army after the 1994 civil war to calls for southern secession.

Another challenge to Saleh’s regime came as Al-Qaeda began solidifying its presence on the ground after its branch in Yemen merged with its branch in Saudi Arabia in 2009. The group had been active in Yemen for some time, targeting foreign tourists and governmental institutions, with its major operations being the attack on the USS Cole in the Gulf of Aden in 2000.

Saleh continued to manage such crises without providing real solutions. After leading an initial crackdown on Al-Qaeda in Yemen, US criticism of Saleh’s record on corruption led him to tolerate a degree of Al-Qaeda activity as a hedge against policy shifts from the US, according to analyst and researcher Gregory D. Johnsen.[123] US drone strikes resulted in the killing of civilians in tribal areas of Marib, Shabwa, Abyan and Hadramawt, increasing hostility against the regime. Many of those who turned to Al-Qaeda did so out of a desire to avenge such attacks.

Tribes and Revolutions

In 2011, a revolution inspired by the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt erupted in Yemen. Led by the youth, many tribesmen and tribal sheikhs peacefully joined in due to their resentment against the Saleh regime. They did so not only representing themselves, but also their tribes.

Among the most prominent figures and parties who joined the revolution were the sheikhs of the Hashid[124] and the Houthi movement.[125] The latter had been practically at peace with the state since February 2010, yet there were still unresolved disputes over control of Sa’ada and surrounding areas. The Houthi movement had by this stage gained the support of many tribes against the regime, but had also antagonized other tribes, as outlined in more detail below.

Saleh ceded power in February 2012 and handed the reins to his vice president, Abdo Rabbu Mansur Hadi, a southern military figure who had fled the South following the 1986 civil war. In March 2013, the National Dialogue Conference was held. The internationally-backed event aimed to bring together delegates from all Yemeni constituencies to plan the building of a modern Yemeni state, including tribal sheikhs influential at both the tribal and political levels.

Despite the conference, Houthi forces continued operations in the north, blowing up houses belonging to sheikhs from tribes which opposed them. In July 2014 they organized the demolition of buildings belonging to the Al-Ahmar clan in Amran.[126] These actions were undertaken in collusion with former President Saleh and his tribal and military loyalists, who entered into an alliance with their former Houthi enemies.[127]

By September 2014, the Houthis had seized Sana’a and Hadi had been forced to submit his resignation, later fleeing house arrest in the capital to Aden. By March 2015, Houthi-Saleh forces had advanced into Aden, forcing Hadi to flee once again. Saudi Arabia launched a military intervention on March 26, 2015, leading a coalition of nine countries. The coalition intervened at Hadi’s request and in conjunction with his escape towards Oman in the east.

Internal Loyalties, Shifting Alliances, Changing Divisions

The presence of the tribes as a key factor in Yemen’s recent conflicts can be divided into four phases. The first is from 2008 to Yemen’s Arab Spring-inspired revolution in 2011; second, from the revolution until the Houthis seized Sana’a in 2014; third, the subsequent phase of the war that saw the Saudi-led military coalition’s intervention and continued until the Saleh-Houthi alliance broke up at the end of 2017; and finally, the contemporary arrangement of power in the conflict.

During these four phases, the map of tribal alliances has contributed to the changing political and military balance of power. Previous “givens” have also changed; enemies have become friends, historical alliances have ended, established powers have collapsed and newer powers have emerged to become major actors in the conflict. In addition, while in northern, Zaidi areas – where, to some extent, the tribal inhabitants sympathized with the Houthi movement – the Houthis have encountered fierce opposition from the Shafi’i tribes in west Hajjah, Al-Bayda, Al-Jawf and Marib.

Phase I: 2008 to 2011