Executive Summary

Since 2021, Yemenis have become more strident in their calls for new and better ways of providing aid.[1] Yemeni experts have warned that prolonged cycles of short-term humanitarian aid can entrench dependence and have called for a transition toward development approaches that could set the foundation for a sustainable post-conflict economy.[2] Despite vastly different interpretations and positions over what development means in practice, this shift is now happening, albeit slowly.

New frameworks and coordination mechanisms are emerging from the UN compound in Sana’a, the World Bank offices in Amman’s Abdali Boulevard, and the conference rooms of Riyadh and Brussels, which are set to fundamentally change the way aid is delivered in Yemen over the coming decade. The effect of these new approaches will take time to be felt on the ground, but the changes are fundamental and irreversible.

The operationalization of this transition has largely been through the establishment and work of the Yemen Partners Group (YPG), which includes donors, the UN leadership, and the World Bank. The YPG has been mandated with providing better coordination and accountability across a range of programming modalities under the humanitarian-development nexus. It has put the humanitarian to development transition firmly on the donor and UN agenda in Yemen, but critics point out that the lack of a clear common definition of what the nexus means in practice provides room for many agencies to rebrand their projects without making fundamental change. The YPG is also heavily skewed towards international actors. It will need to find ways to broaden decision making without collapsing under its own weight.

The transition from humanitarian to development aid has presented opportunities for building a sustainable and inclusive economy. Yemeni actors interviewed for this report, including aid and economy areas and leaders of local and national aid organizations, spoke of areas of improvement, including better alignment in the aid sector; more creative implementation of development and humanitarian approaches in parallel; longer timelines, including multi-year funding; and more sustainable approaches, including greater inclusion of host communities. Larger Yemeni aid actors reported having a greater ability to influence the agenda, though local organizations said they struggle to compete.

However, the development system is a fundamentally different beast compared to its smaller humanitarian cousin. These differences can be subtle, as the programs often look similar on the ground. Both humanitarian and development actors in Yemen have provided cash payments to poor families, and upgraded schools, health clinics, and water networks. However, the development system is less willing to take on risk and sets far higher standards for its partners. A divided government, ongoing conflict, money transfer restrictions, and an entrenched war economy make Yemen a hostile environment for traditional development approaches. Yemeni actors may find themselves having to work much harder to position themselves as credible development partners.

The development system is also inherently more political. Without sufficient local feedback, the transition from humanitarian to development assistance risks further exacerbating the economic, governance, and conflict fault lines dividing the country.

In the context of declining global humanitarian funding levels due to competition from operations such as Ukraine, and an increasing wariness of the risks of investing sustained development assistance in Yemen by many international donors, Yemen is at a dangerous crossroads. As efforts towards a peaceful solution to the conflict falter in the wake of the war in Gaza, Yemen risks becoming another forgotten crisis, as humanitarian funding dries up, and more sustained interventions are inhibited by an ongoing situation of “no war, no peace”.

Looking ahead, key risks posed by the transition include:

- Donors continue to be nervous of investment in development in the absence of an expected peace agreement, raising the risk of a protracted stalemate with depleted humanitarian assistance but insufficient development support.

- Without progress on peace talks, it is difficult to see how Yemenis can develop a coherent national framework to guide development funding and build international confidence that Yemen is a promising partner for large scale development funding.

- There is a shallow understanding of internationally funded development among some Yemeni authorities and members of the public, and it is often lauded as unambiguously positive.

- Development actors continue to struggle to effectively own the political fallout of their decisions. Coordinating and working directly with local actors may be the only available option, but it risks entrenching fragmentation.

- There is a lack of clear evidence that progress on strategic planning has resulted in effective changes in implementation on the ground.

- Humanitarian needs will remain, amid a worsening funding landscape. The risk of moving quickly toward development is that direct aid to the most vulnerable communities will be affected as humanitarian resources dwindle in the absence of government or development funded social safety nets to fill the gap.

- Money (and therefore decision-making power) continues to flow through a narrow set of hands, which makes it difficult for even the best intentioned policies and frameworks to force change in favor of greater Yemeni ownership and leadership of the development agenda.

While a shift to long-term development is a worthy goal, realistically, Yemen will be in a messy no man’s land between humanitarian and development for the foreseeable future. The good news is that a number of new approaches and frameworks, including the humanitarian, development, and peace nexus, aim to strengthen aid delivery in transitional contexts. The success of aid endeavors over the coming decade will be decided by how successfully Yemen can harness these transitional approaches.

Yemen has the potential to benefit enormously from new transitional nexus approaches, especially if they are able to build upon concurrent progress towards a sustainable end to the conflict. However, if key Yemeni actors are unable to effectively inform the agenda, or if the international community does not learn from past mistakes, it risks becoming a cautionary tale.

The nexus refers to efforts to foster greater coherence among actors working to strengthen resilience in fragile contexts, drawing on humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding approaches. The concept draws on previous efforts to find more effective ways to work in the gap between traditional emergency and development programming, but gained prominence when it was adopted by the UN and World Bank in the New Way of Working (2017) and by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) in 2019.[3]

However, beyond a general understanding of the nexus as a way of coordinating an aid response towards a set of common goals, there continues to be a huge disparity in both the understanding and implementation of the nexus in crisis contexts across the globe. Many have differing views of what the nexus means “in practice”, and nexus strategies being implemented at the country level are often very context specific, and differ considerably even from those in other countries with similar contextual dynamics. According to one interviewee, the nexus debate continues to be largely led by people sitting in regional or headquarter offices, with little involvement in the actual implementation of projects on the ground. Divisions over how to implement the nexus are significant in Yemen, with a range of interviewees from different international and national organizations expressing a lack of understanding of, or disagreement with, current approaches.

Methodology

This assessment focused on how the aid community has adapted its approach in Yemen since the publication of a number of landmark critiques in 2021 and 2022.[4] It is based on a qualitative and strategic approach to identify opportunities to promote stronger engagement across the aid-economy nexus and strengthen local voices in the design and delivery of aid in Yemen.

The research team interviewed 31 development and humanitarian actors working on Yemen and 12 Yemeni aid and economy experts to identify the key changes in the way aid has been planned and delivered since 2021. The interview guide is attached as Annex 1.

The research team also sent out a digital survey to which 64 Yemeni aid and economy stakeholders responded, providing input on their perception of the aid-economy nexus in Yemen, challenges, and ways forward. Survey respondents included representatives of civil society (65 percent), government (19 percent), the private sector (14 percent), and academia (2 percent). The majority of the Yemeni stakeholders worked at the national level (covering both government- and Houthi-controlled areas), with 23 percent at the local or subnational levels. In terms of gender considerations, 46 percent of participants in this research were women. The survey is attached as Annex 2.

The research team also undertook a desk review of key documents published since 2021.

Based on the interviews, survey findings and desk review, the research team mapped out the risks and opportunities posed by the nexus transition and identified a number of recommendations for both Yemeni and international actors to ensure that aid investment helps build the foundations of a sustainable post-war economy.

Limitations

The nexus approach focuses on bringing together humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding approaches. This paper is concerned with how Yemen can better leverage aid to support a sustainable economy. As a result, it mainly focuses on the transition from humanitarian to development aid and gives only limited attention to the role of peacebuilding approaches in Yemen. This paper did benefit from a review by a number of peacebuilding experts.

This paper focuses on the traditional aid industry, namely aid that is channeled through Organization of Economic Development – Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) criteria for development aid or Humanitarian Response Plans. There is a growing body of literature on the rise of non-traditional aid donors (including philanthropy and states that largely operate outside of OECD-DAC rules, like China and the Gulf states). Other financial flows, like investment and remittances, also play a major role in development but are beyond the scope of this study.

Lastly, there is a growing body of literature calling for fundamental changes to the way aid is delivered, including decolonizing aid and the localization of decision-making. While fully supportive of these aspirations, this paper starts from a more pessimistic assumption that traditional aid funding decisions will largely continue to be made in Western capitals for the immediate future. While fully supporting more radical changes, we assume that the extent to which Yemeni actors will be able to leverage foreign aid for sustainable economic development will largely depend on their ability to influence the thinking of traditional aid donors, at least for the immediate term.

All interviews were conducted online, based on the existing networks of the authors and the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. This brought significant efficiencies and allowed the research team to access opinions from aid and economic decision-makers who are spread throughout Yemen and regional/global capitals. However, the views and opinions in this paper are skewed toward people who make up the traditional decision-making elite and have access to stable online communication tools. This study will not represent the views of digitally marginalized groups or other traditionally excluded groups.

Taking Stock of Aid in Yemen

Before addressing the major changes in the aid system since 2021, it is useful to briefly assess the development of the aid sector in Yemen over the past few decades.

Following the unification of Yemen in 1990, the World Bank and other major development actors began to invest in service delivery and infrastructure. Due to concerns about corruption and weak state capacity, the World Bank set up a number of parastatal organizations to channel aid funding, including the Social Fund for Development, which continues to play a major role in supporting cash assistance and social safety nets, and the Public Works Committee.[5] Development programs were largely halted in early 2015, following the takeover of the Yemeni capital Sana’a by the Houthi group (Ansar Allah).[6]

The Houthis takeover of Sana’a triggered a Saudi-led coalition intervention in March 2015, which sparked fears of a major humanitarian catastrophe in Yemen. In July 2015, the UN declared an L3 emergency, its highest-level humanitarian response.[7] Global humanitarian agencies, many of whom had a limited presence in Yemen, rushed to scale up or establish new operations. Humanitarian aid funding skyrocketed from US$430 million in 2014, less than 2 percent of global humanitarian funding, to US$5.2 billion in 2018, 20 percent of global humanitarian funding. This made Yemen the largest-ever humanitarian response in dollar terms.[8]

Most of this funding was raised through UN-led appeals; the rest came from actors outside of the UN-coordinated system, such as the UAE Red Crescent or the Saudi Reconstruction and Development Program for Yemen.[9] By 2022, 200 humanitarian organizations (12 UN agencies, 58 international NGOs, and 130 national NGOs) were active across all 333 districts of Yemen,[10] though many organizations struggled to consistently access areas outside of major cities.[11] Some major national aid actors, such as the Yemeni Red Crescent Society, Yemen Family Care Association, and Social Development Fund, have national reach and have been able to exert considerable influence on how aid is delivered. However, smaller local NGOs, especially those based in rural areas, often lack the resources and capacity to engage effectively with decision-making, which takes place in Yemen’s major cities or abroad.[12]

A growing global focus on how to bridge the humanitarian-development nexus provides an impetus for reform in Yemen. Since the mid-2010s there has been a growing recognition that traditional approaches to aid delivery, constituting short-term humanitarian aid to meet emergency life-saving needs and long-term development aid to build national capacity and promote economic growth, do not function well in protracted conflicts. Global frameworks like the Grand Bargain (2016), the Humanitarian Peace and Development Initiative (2016), and the UN’s New Way of Working (2017) have sought to promote sustainable, locally-led solutions that cut across the humanitarian, development, conflict, and economic divide.[13] The Grand Bargain called for “at least 25 percent of humanitarian funding to go to local and national responders as directly as possible to improve outcomes for affected people and reduce transaction costs,” though only 2 percent of funding went to national organizations worldwide in 2021.[14]Yemen is a priority country under both the nexus initiative and the New Way of Working.[15]

Aid projects (both development and humanitarian) can look similar when it comes to delivery on the ground. But there are ideological differences that influence how and where aid is delivered.

Humanitarian action traces its ideology back to the Battle of Solferino in 1859, where local volunteers sought to provide neutral support to soldiers wounded on the battlefield.[16] Humanitarian action is guided by International Humanitarian Law, overseen by the International Committee of the Red Cross. Humanitarians operate by four principles: humanity, neutrality, independence, and impartiality, and generally focus on negotiating access to affected people to provide immediate, life-saving support.

Key humanitarian actors include the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), Medecins San Frontieres (MSF), and European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO).

Development action was largely founded in the post-World War II order. Development actors traditionally work through partner country systems and focus on issues like building long-term inclusive and sustainable economic growth, poverty eradication, improving living standards in developing countries, and ending aid dependence. Development action is governed by the OECD-DAC[17] (though major emerging donors like China do not participate) and guided by the Sustainable Development Goals[18] and the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005).[19]

Major development actors include the World Bank, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the US Agency for International Development (USAID). Many organizations, like the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Cooperative for Assist and Relief Everywhere (CARE), and the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO) have multiple mandates, and can do humanitarian, peacebuilding and development work.

Humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding actors have increasingly recognized the need to work together to address complex crises. This is described as the nexus approach. This in turn reflects an important reality, that in many contexts humanitarian, peacebuilding or stabilization, and development programming looks very similar. One interviewee for this report from a major UN agency pointed out that in one recent country they had worked, one UN agency was building schools under stabilization funding, another under humanitarian funding, while a third was supported by the World Bank under a development mandate. The difference was the way in which projects were selected and why. However, the end result for the communities was the same.

Saudi Arabia, the US, the UAE, and Germany have been the major donors of humanitarian and development assistance to Yemen since 2015.[20] The majority of donors, with the exception of ECHO, the EU humanitarian agency, are based outside of Yemen. This, in addition to the language barrier, has made it challenging for local Yemeni organizations to connect directly with donors, who ultimately decide what priorities to fund. This was made more difficult in the absence of intermediate mechanisms to help prioritize and coordinate funding in a way that involves strong engagement from local actors. For example, the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF) for Yemen was only released in 2022.[21]

Gulf donors have supported the formal humanitarian system, but they largely prefer to fund humanitarian work through their own mechanisms. Saudi Arabia provided US$1 billion in unearmarked[22] support to the UN appeal for Yemen in 2018, the largest ever non-earmarked humanitarian contribution. However, Saudi Arabia did not renew its support for 2019, reportedly due, at least in part, to its dissatisfaction with the lack of tangible results.[23] Outside of UN appeals, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have largely directed their humanitarian funding through the Saudi Reconstruction and Development Program for Yemen and the UAE Red Crescent, respectively.[24] Other, less formal mechanisms, such as the one-off Famine Relief Fund, funded by “private Gulf interests,” have also played an important role in channeling hundreds of millions of dollars to humanitarian responders in Yemen.[25]

The scale up of humanitarian aid to Yemen was largely justified by the UN as a response to impending famine. While supporters of the UN response argue that the famine narrative was successful in mobilizing aid funding in a complex and high-risk environment, critics argued that the narrative led to overinvestment in food handouts and short-term solutions which entrenched dependency.[26] Over 50 percent of funding in Yemen has been directed to the food cluster, compared to around 25-30 percent in other major crises such as Iraq or Syria.[27] The approach was also criticized for being disconnected from Yemen’s pre-conflict situation, where poverty and economic instability were the primary contributors to food insecurity.[28] Rather than understanding how the economic ramifications of the conflict were exacerbating pre-existing vulnerabilities to drive huge levels of humanitarian need, and addressing these drivers within the context of the conflict, large-scale, short-term interventions were prioritized, reactive to and focused on responding to the immediate needs of famine and cholera outbreaks.

The need to scale up quickly saw many humanitarian organizations make short-term compromises, like allowing authorities to place restrictions on data collection and access to beneficiary lists, which undermined trust in the response. This was especially true in Houthi-controlled areas.[29] Research conducted by Humanitarian Outcomes in 2022 found that “most Yemenis surveyed were not able to name specific humanitarian actors or judge which of them were most present and effective.”[30] The lack of Yemeni monitoring and accountability mechanisms and questions regarding the transparency of data have further contributed to the ineffectiveness of aid and the seemingly disorganized response.[31] To further complicate matters, the scale of the humanitarian response makes it a major pillar within the broader economy, and a significant source of rents for actors adjacent to the “industry.” This has put aid on the frontlines in the battle to control Yemen’s political economy.

How Has the Aid Community Evolved Since 2021?

2021 was a watershed year for the Yemen response. The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies published a series of reports that were highly critical of the aid response.[32] This was followed up by studies by international organizations, including an independent evaluation conducted by the top global body for humanitarian aid, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee, which largely echoed the Sana’a Center’s findings.

Key gaps identified by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee evaluation included: Too much focus on short-term humanitarian aid; poor oversight of aid; and too much reliance on fragmented and dubious quantitative data.[33]

The evaluation did note with sympathy that the humanitarian system was being called on to keep Yemen’s social infrastructure functioning, often acting at times as a “shadow government.”[34] This role is well beyond the funding, mandate, or expertise of the humanitarian system. The evaluation called on the international community to “advocate with donors for more long-term investment in economic opportunities, employment, and sustainable livelihoods.”[35]

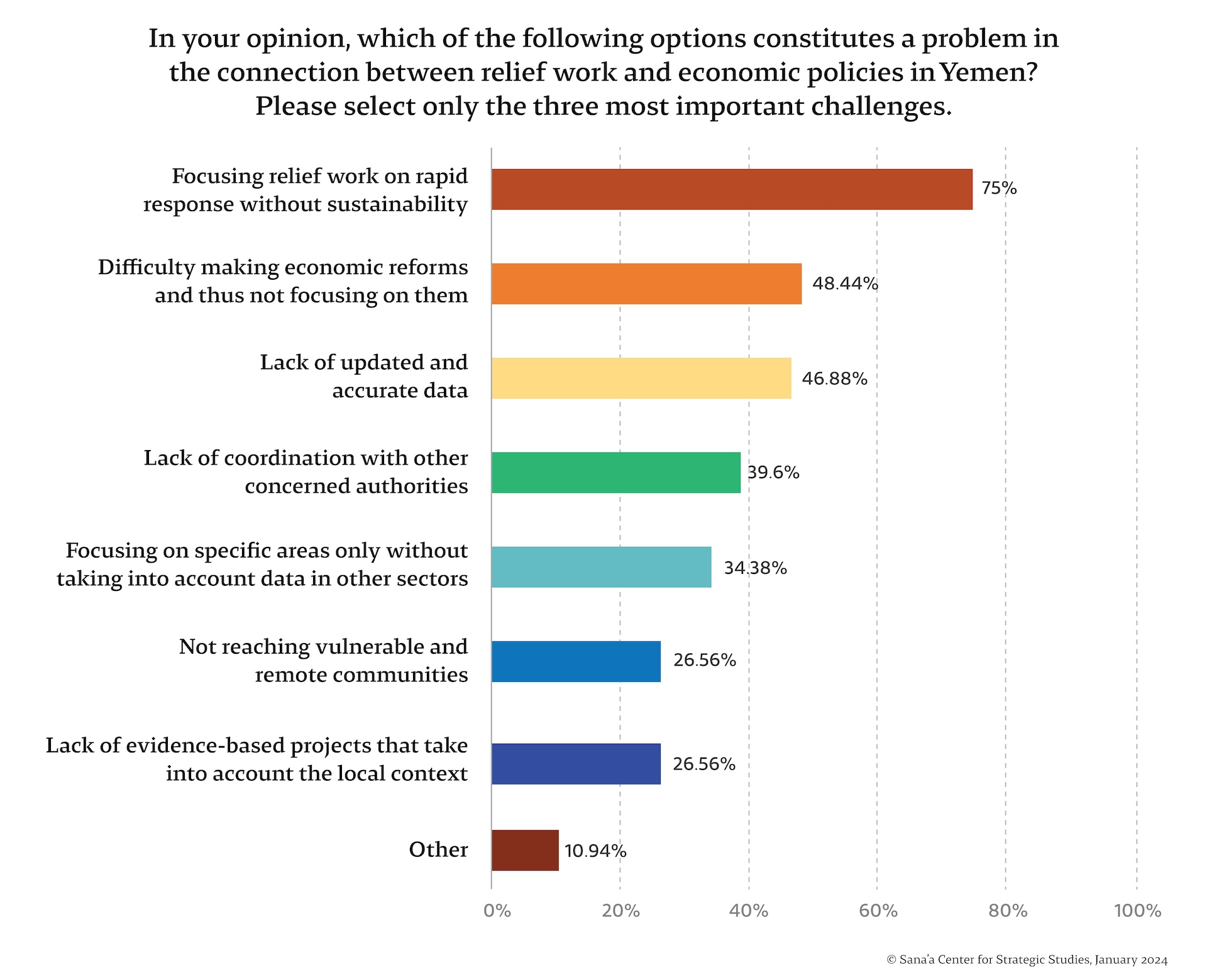

Yemeni experts interviewed for this study cited short-term approaches to aid delivery as the key barrier to effective support. In a survey of 64 Yemeni aid and economy experts, 75 percent said that focusing relief work on rapid response without appropriate efforts to make it sustainable was one of the top three barriers to better-leveraging aid to promote a sustainable economy. Almost half named barriers to economic reform as a key barrier.

Figure 1. Survey results on barriers to leveraging aid to support a sustainable economy in Yemen

Though less in the spotlight, development actors, many of which continued to be present in Yemen in various forms during the peak years of the humanitarian response, also had room for improvement. Two years ago there was little to no effective coordination among development donors, despite significant development funding continuing to reach the country.[36]

In response to these criticisms, the international community began to rethink the way it plans and coordinates aid in Yemen. Since 2021, the UN-led response under Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen David Gressly implemented a number of strategies and systems to implement a transition from humanitarian to sustainable development, as part of a broader objective of “preparing for peace,” noting that humanitarian assistance will continue to be required for a number of years.[37] These included an Economic Framework, a UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework, stronger engagement with development actors and donors, and a number of agency-specific strategies aimed at enforcing greater accountability for action along the humanitarian and economic development nexus.

The operationalization of this transition has largely been through the establishment and work of the Yemen Partners Group (YPG), which includes a range of stakeholders, including donors, the UN leadership, and the World Bank. The goal is to provide better coordination and accountability across a range of programming modalities under the humanitarian-development nexus.

Table 1. New platforms introduced to promote sustainable approaches to aid in Yemen

|

Platform |

Key features |

|---|---|

|

The UN Yemen Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework 2022 to 2024 |

Sets out priorities for development cooperation in Yemen, focused on: increasing food security, improving livelihood options and job creation; preserving inclusive, effective, and efficient strengthening of national and local development systems; driving inclusive economic structural transformation; and building social services, social protection, and inclusion for all. |

|

World Bank multi-donor trust fund |

Seeks to attract reconstruction and early recovery funding for Yemen from donors, in line with the Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework. This model has also been used to support sustainable development and recovery in other high-risk contexts such as Iraq.[38] |

|

The UN Economic Framework |

Led by the UN Resident Coordinator (RCO), it seeks to introduce sustainable approaches across the aid-economy divide. |

|

The Yemen Partners Group (YPG) |

Led by the World Bank and the EU, which took over for Germany in December 2023. The YPG seeks to improve coordination between development partners and donors. It has a number of technical teams covering topics such as area-based approaches, the Mahram issue, durable solutions, and key focus areas like water and food. |

|

Food Security Preparedness Plan |

Led by the World Bank and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. It focuses on attempts to introduce sustainable approaches to food security in Yemen. |

|

Development Partners Forum |

Chaired by the World Bank in collaboration with the UN Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen and the UN Resident Coordinator, the internationally recognized Yemeni government, and regional donors, the Development Partners Forum aims to discuss topics across the humanitarian, peace, and development nexus at the agency level. |

|

Informal high-level coordination meetings on Yemen’s economy |

Led by the EU. Informal meetings between donors supporting Yemen’s economy. |

|

Yemen International Forum (YIF) |

Led by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. The YIF is the largest international annual conference for Yemeni-Yemeni dialogue. It forms part of a larger Yemeni-led and designed initiative and longer-term process that includes consultations with Yemeni experts and stakeholders, production of research, and extensive regional and international shuttle diplomacy.[39] |

|

International Gender Coordination Group |

Led by the EU and UN Women. Informal meetings between donors supporting gender equality in Yemen. |

The Yemen Partners Group (YPG) and its Yemen Partners Technical Team (YPTT) are the main strategic instruments for implementing the nexus between humanitarian and development aid in Yemen. The YPG was established to strengthen humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding coordination in Yemen among non-Yemeni stakeholders. It aims to align the priorities of UN agencies and the international community and was set up in response to a recommendation in the Inter-Agency review to develop a coordination architecture that includes development partners, not just humanitarian actors. It includes a range of stakeholders, including UN agencies, the UN’s peace negotiations team, the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General to Yemen (OSESGY), donors, and development partners like the World Bank. It aims to align strategic priorities and promote effective coordination around the implementation of nexus approaches in Yemen. The YPG is co-chaired by the UN Resident Coordinator, the World Bank, and a donor country on a 12-month rotational basis. It meets every two months at the same time as the United Nations Country Team (UNCT). Participation includes UN Heads of Agency and the Heads of Cooperation from embassies, although this can be raised to the ambassadorial level on an ad hoc basis. Other participation, such as from civil society or national authorities, can also take place on an ad hoc basis.

The YPG is supported by a technical group, the YPTT, to identify strategic priorities and opportunities for intervention. The YPTT is essentially the implementation arm of the YPG and is tasked with taking forward agreed priorities and identifying pilots for nexus- and area-based programming approaches. Membership includes representatives of the RCO, UNOCHA, World Bank, and OSESGY. Up to seven UN agencies can participate, and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), government, or civil society representatives can be invited on an ad hoc basis. The YPTT is co-chaired by the UN Resident Coordinator’s Office, OCHA, and a donor. Meetings are held monthly and set the agenda for the Yemen Partners Group meetings.

Transitioning to a More Integrated and Nexus-Aligned Response

Tangible Improvements

Across the nexus there have been tangible improvements. The UN was able to negotiate a deal with the Houthis in 2023 for an operation to transfer oil from the dilapidated FSO Safer oil tanker, removing a long-standing environmental and economic threat.[40] Interviewees noted an improvement in the extent to which donors, large development actors, and multilateral institutions were engaging with, and coordinating around, multiple issues, ranging from technical assistance to governing institutions for macroeconomic stabilization and more sustained and better-coordinated development interventions.[41] There has been a notable improvement in engagement from large actors such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Overall, there is much better alignment in the aid sector. One humanitarian donor remarked that, up until 2021, there was no united front among aid actors when dealing with joint issues. Organizations individually sought compromises for benefits such as increased access. There is now more unity in negotiation and approach. The YPG has facilitated more robust decision-making processes and greater unity on how the international community approaches issues like Mahram regulations on aid workers,[42] healthcare incentives, program approvals, and the issuing of visas.[43]

In practice, the line between humanitarian and development assistance has become blurred. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The prevailing critical narrative on aid in Yemen has largely drawn a clear division between humanitarian and development funding as two entirely distinct modalities of operation, where one needs to be reduced and the other increased. The reality in Yemen, however, is more nuanced. One donor commented that describing the transition from humanitarian to development aid in Yemen is problematic. Aid delivery in Yemen is layered and complex, regardless of its source.[44] A range of interviewees noted that a large proportion of development assistance being delivered in Yemen appears, for all intents and purposes, to be humanitarian. Examples include large-scale social protection programs where a large percentage of recipients may also require emergency assistance. On the other hand, many humanitarian programs are no longer ad-hoc, traditional life-saving interventions such as water trucking, but non-traditional and more sophisticated life-saving interventions with longer-term impact. For example, the aid response in Taiz governorate has transitioned from water trucking, to the emergency rehabilitation of wells, and later to a broader approach that focuses on restoring the water network and building the institutional capacity of the local water corporation.[45] Support to camps for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) is also increasingly focused on constructing longer-term structures, reflecting the reality that many of these displaced communities have become more settled.[46] One donor emphasized the need to get away from the notion that only development funding is achieving development objectives and vice versa. This nuance is important to provide a more holistic understanding of how the aid response is working, and how it should work in the future.

Aid actors are increasingly taking a layered, rather than sequenced approach, simultaneously implementing development with humanitarian approaches. There have been positive developments among certain donors and implementers, both globally and in Yemen, toward simultaneously addressing humanitarian and development needs. Some pilot projects, such as the Cash Consortium of Yemen, are actively testing this approach. The initiative would see Multi-Purpose Cash Assistance being implemented at the same time as business and income generation activities, to provide pathways out of aid dependency. A range of other donor-led initiatives are piloting similar approaches.[47]

Yemeni aid and economy actors report seeing some tangible improvements since 2021. This includes longer timelines for aid interventions (a year or more, compared to six months), inviting Yemeni organizations to donor coordination meetings and clusters and engaging local communities in needs assessments. However, these improvements, although encouraging, are lacking in terms of understanding the ecosystem in which local partners operate. For example, while one year is better than six months, local aid workers report that half of the year is wasted obtaining licenses from local authorities and recruiting staff. This is not sufficiently considered in planning, so local partners find themselves trying to deliver a year’s worth of outcomes in six months. And while Yemenis are invited to attend coordination meetings with the international community at the national and even international levels, they do not receive sufficient support in terms of logistics and travel requirements, which impedes their participation. This is especially true for women, who face more barriers in terms of mobility.

Yemeni aid experts told us they have seen some aid responses switch to more sustainable approaches. The World Bank and UN are investing in solar power for schools and health clinics to help address energy shortages. In Taiz, donors are working with local authorities and representatives from civil society to reform the water network and empower state institutions to take on this responsibility, though local experts complain that work is progressing slowly. These are positive changes, but many Yemeni aid actors reiterated that too much aid is still building dependency, especially around support for displaced people.

Experts also reported the introduction of multi-year funding for some projects. This is crucial to help aid actors address underlying causes of issues such as displacement with effective, durable solutions that do not build dependency. Yemen’s crisis is a protracted one, and displaced people are considered long-term settlers rather than temporarily relocated.[48] They have created makeshift homes in host communities, where some have been living for five years or more. Carrying out multi-year projects, especially relating to infrastructure, income generation, and basic services, acknowledges the realities of displacement and its impact on both the displaced and the host community.

Yemeni aid workers also felt there had been an improvement in responding to the needs of communities hosting displaced people as legitimate beneficiaries of humanitarian projects. This is especially true for interventions such as water networks, renewable energy, and cash for work. Many of the displaced have become settlers in the host communities, creating economic and social strain, and this approach has been welcomed as a part of rebuilding local economies.[49]

Larger Yemeni actors, such as national and well-established civil society organizations, report being able to engage with donors and influence decisions. Stronger and more experienced Yemeni partners are finding themselves in a better position to coordinate assistance and represent local communities. A senior director of a national development organization said, “We are able to negotiate with the implementing agencies and, if they do not respect our input, we can go above them to the donors and make our case as the Yemeni partner. Because we have the connections, skills, and strategic vision, we are able to greatly influence the way projects are implemented. Other smaller organizations have no choice but to do as they are told. Otherwise, they risk losing the project.”

More donors are on the ground, and many UN agencies have made efforts to display a “shift in mentality.” UN workers argue that many of the gaps identified in 2021 have been addressed through various efforts, to varying success. Strategically, the response has shifted from addressing “famine” to a broader, more coordinated food security and crisis protection framework, involving extensive coordination between humanitarian and development actors.[50] However, the humanitarian response continues to face challenges, including limited presence of aid workers outside Sana’a and Aden, ongoing access restrictions and outdated, poor-quality data.[51]

Lofty Goals, Mediocre Progress

Despite the improvements noted above, skepticism exists on how well the nexus is being implemented in practice, and whether current approaches reflect meaningful changes to a deeply problematic response.

There is a general consensus on the importance of the nexus. However, many aid actors in Yemen believe the lack of a clear understanding of what the nexus means is undermining implementation. There was almost universal agreement among those interviewed that there is little consensus on what the humanitarian, peace, and development nexus means to Yemen. According to one interviewee, nexus discussions have been ongoing in some form since 2016, “yet here we are, still discussing, and the reality is [that] most people working on the nexus still don’t know what it means.”[52] One interviewee commented that they do not believe the humanitarian community at large is leveraging the nexus conversations taking place at strategic levels to make real, tangible changes on the ground. Divisions among aid actors were reinforced by recurring criticism of the nexus approach being pushed by UN leadership. Putting it bluntly, one interviewee felt that those leading the discussion were not qualified, describing it as “dentistry being done by plumbers.”[53] One recurring demand was a broader articulation of the plan for the next steps within the nexus strategy, which some have argued currently does not exist.

Some interlocutors raised the fear of projects being rebranded as nexus approaches without any real change. Many Yemeni and international interviewees commented on the lack of consistency among interpretations of what nexus programming is, and noted that there is no practical understanding on how to implement nexus programming, beyond a lot of conceptual guidance. Another said that while the shift in strategies and objectives among the aid community is positive, in practice many organizations use nexus language to frame programming that has not, in essence, changed a great deal in approach, modality, and impact. One international NGO respondent noted that many projects are being “reverse-engineered” to fit into nexus strategies. One interviewee even saw the nexus as a form of exit strategy for a humanitarian response already dealing with major funding shortfalls, allowing actors to pivot to other forms of programming more motivated by business continuity than real needs.[54] “The [humanitarian donor] landscape is drying up. The Humanitarian Response Plan was only 30-40 percent funded for 2023, and organizations are desperate for new funding sources.”[55]

Yemeni stakeholders raised similar fears about how the nexus approach was being implemented and expressed hopes the nexus could better empower Yemeni partners to carry out sustainable aid work. This requires strong and regular coordination and capacity building in order to provide long-term support for target communities and vulnerable groups. Yemeni economic experts confirmed that some local authorities have clear plans for the transition from humanitarian work to development through a multi-year recovery plan. For example, the government-aligned Taiz Governor and representatives of Yemeni and international stakeholders have been working on operationalizing the nexus through a three-year transition project to provide basic services, starting with the water sector.[56]

While there has been significant improvement, coordination challenges among international donors, NGOs, and UN agencies remain a significant obstacle to progress. There continues to be significant division among donors on how to approach coordination on Yemen. Coordination has worked best when responding reactively to specific issues or crises – but less well on proactive efforts ahead of these crises. This also speaks to the dynamics between the UN and donors. UN leadership has been highlighted as critical to avoid donors having too much influence on particular issues, especially large donors with greater sway. Interviewees were concerned that funding levels ultimately determine the strength of influence on sensitive issues requiring broader consensus. The UN continues to be cited as the best actor to lead on these issues as an ostensibly impartial voice. However, some concerns were raised that the UN itself is highly divided, with agencies taking different stances and easily influenced by donors with large portfolios. Concerns have been raised that some donors are encouraging this division, and manipulating the UN system and international aid architecture more broadly. Fragmentation within the donor community will ultimately result in fragmentation on the ground, promoting disjointed programming and weakening the response.[57]

One interviewee pointed out the difficulties in formulating a coherent approach among donors in the nexus, due to the internal structures and processes of the donors themselves. Donors have “different mandates and DNAs.” Some are more flexible than others. Donors with combined humanitarian-development portfolios are seen as more effective. Overall, a greater emphasis on joint programming is needed. More effort needs to be made to pilot simultaneous and coordinated humanitarian and development programming, rather than seeing one as following the other. While some successful projects have been implemented, as noted above, there appears to be a lack of coherence across the donor landscape in taking successful approaches to scale in a coordinated fashion.[58]

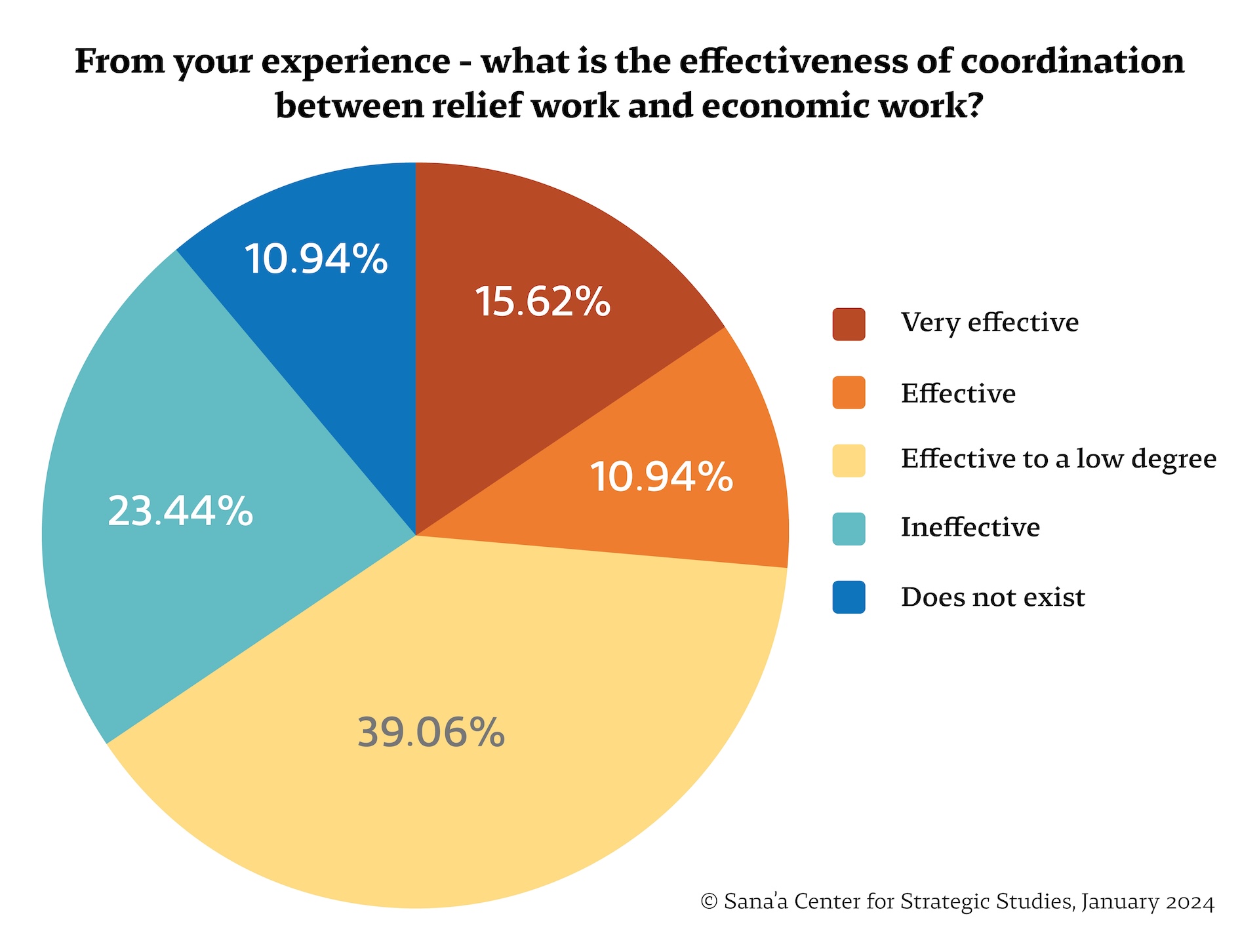

Yemeni stakeholders raised similar fears. Almost two-thirds of Yemeni aid or economy experts interviewed for this study thought that efforts to coordinate across the aid-economy divide were ineffective (24 percent) or effective only to a low degree (40 percent).

Figure 2. Survey results on the effectiveness of coordination between aid and economic work in Yemen

While a good step forward for the nexus, the Yemen Partners Group (YPG) has been criticized for being slow, unwieldy, and unrepresentative. Many voices continue to be largely missing from the group’s major processes and exercises. The Yemen Partners Technical Team (YPTT) was mentioned in several interviews as lacking sustained Yemeni civil society or NGO participation, local or international. Other criticisms centered on the technical team’s reliance on humanitarian clusters. Without senior decision-makers in the room, discussions can get lost in process issues.[59] Others criticized the YPG and its working groups for being too slow and unwieldy, and overly focused on process over outcome.[60] Senior aid officials said the focus needs to be on understanding to what extent the YPG and other efforts have led to donors shifting their strategies.[61] However, despite these criticisms, the consensus among donors, UN officials, and INGO workers was that the YPG was a step in the right direction. Others were more blunt, stating that while it may be too early to judge whether or not the YPG and other mechanisms were failing to meet their objectives, if more practical progress was not achieved in the coming year, it will be just as difficult to view it as a success.

Major barriers continue to impede effective localization. When it comes to increasing momentum around localization, one senior international non-governmental organization official argued that, while there have been strategic commitments to this, major institutional barriers remain. Notable is the complexity of UN sub-award systems – the way in which the UN allocates donor money onwards to implementing partners. By their nature, they often present insurmountable barriers to local organizations and are somewhat hypocritical given the relatively low level of accountability many UN agencies face regarding spending their own funds. A representative of a local organization based in Marib complained that the application process for funds is complicated and has many requirements that they could not fulfill considering their size and stretched resources. “They [UN agencies and donors] put us at the same level with a national, well-established organization that has strong institutional structures. We are barely able to keep the lights on, let alone pay for annual audits and make sure all our staff have regular training. We are able to achieve the same results, if not better, because we know our work and we know our community, who trust us. But, because we cannot check the right boxes, we are excluded. This is unfair, and it creates a vicious cycle because when we are excluded we are unable to grow and improve our institutional capacities.”

Many local partnerships are presented as evidence of localization efforts by international organizations, but more accurately reflect “risk dumping” on local partners operating in high-risk or heavily politicized areas, rather than genuine support and capacity building. Aid experts expressed fears that international organizations were shifting security and other risks away from themselves by moving much of the on-the-ground implementation to local organizations through partnerships.[62]

According to the head of a development civil society organization in Hudayah, international organizations do not give much consideration to their exit or phasing out plans. This is dangerous, as it creates dependency among the beneficiaries. The dependency problem was voiced by almost all Yemeni stakeholders interviewed during this research, who explained that the way aid is provided to vulnerable communities keeps them in poverty.

Additionally, smaller Yemeni civil society organizations complain that grant selection is biased against them, as they can not compete with international development organizations during the bidding process. “The requirements are above our capacity, not only to take part as implementing partners but sometimes to even join clusters and provide our input. We are required to be physically present where the cluster meetings are, and to have a strong internet connection to be able to take part in training courses and be able to communicate. It is like they are disconnected from our reality, that we are struggling just to keep the lights on, let alone dedicate people to travel to attend meetings,” said a representative of a civil society organization operating in a remote area of Yemen.

Approaches to information sharing can also pose risks and entrench corruption. According to a representative of a civil society organization in a conflict-affected governorate, the way that lists of beneficiaries are collected and shared not only is inefficient but puts people who fled on political grounds at risk. The control of local authorities over the disbursement of aid and beneficiary lists has not only reduced the on-ground engagement of INGOs but also created favoritism among Yemeni implementing partners.[63]

Many Yemeni stakeholders emphasized the need to strengthen the role and recognition of the private sector in the long-term economic recovery post-conflict. They cited the role Yemen’s private sector has already played in providing basic goods and overcoming supply chain challenges. The privatization of electricity in northern areas, albeit plagued by heavy manipulation by political actors and limited real competition, has contributed to the availability of electricity, in many occasions powered through solar energy. However, interviewees from the Yemeni private sector reported that international aid is crowding out local businesses and, because of a lack of accountability, aid products end up being sold in the local market at cheaper prices causing disruptions to the local economy.

Fragmentation and power struggles between various governing bodies at the central and local levels cause delays and complications for Yemeni aid workers. For example, in areas controlled by the internationally recognized government, licenses have to be obtained from both the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation and the Ministry of Social Affairs, as well as compliance regulations with the local-level authorities controlled by the Southern Transitional Council.

Major Risks to the International Aid Response

Donors continue to be nervous of investment in development in the absence of an expected peace agreement, raising the risk of a prolonged stalemate with depleted humanitarian assistance and insufficient development support. A senior INGO decision-maker said that when they pitch longer-term programming, donors often respond that they do not think Yemen is stable enough to justify development projects. While stability at the local level exists in some areas, the donor community has yet to take advantage of these opportunities.[64] There is a perception among many stakeholders interviewed that too much weight is being placed on a peace deal as a prerequisite for development implementation and not enough on what can be done if a negotiated settlement is not forthcoming.[65] This is taking on new urgency as the war in Gaza, and Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping, appear to have set back hopes for a breakthrough on peace talks.[66] Another interviewee with an international development agency argued that, even now, too many organizations continue to push for humanitarian over development assistance.[67] This is exacerbated by most of the donor and development communities not being sufficiently present in Yemen. The idea of local “islands of stability” providing opportunities for area-based development interventions was echoed by a range of stakeholders, with many pointing to interesting pilot programs attempting to take advantage of this dynamic. However, this continues to be mostly ad hoc, without a systematic approach to development interventions tailored to the current contextual realities in Yemen, particularly should progress toward a peace agreement falter. There is also fear that this approach will ultimately result in deeply unequal allocation of development resources based on ease of programming, rather than needs.

There is a shallow understanding of internationally funded development among some Yemeni authorities and members of the public, and it is often lauded as unambiguously positive. Development interventions and actors are, by definition, more political than humanitarian initiatives, and need to be approached and assessed differently. Humanitarian needs in Yemen will persist, and emergency assistance must be maintained where needs exist. The increasing momentum linking the humanitarian response to broader nexus and development objectives is real and positive, with many Yemeni stakeholders interviewed for this report citing gradual progress towards more sustainable approaches.[68] However, a more nuanced picture of development assistance needs to be painted in order to understand the inherent risks this shift poses.

According to interviews, international donors, member states, and international financial institutions (IFIs) continue to bias development assistance away from Houthi-controlled areas, due to restrictions imposed by the Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA). Many conversations are reportedly marked by navel-gazing on macroeconomic issues, rather than focusing on where real opportunities exist for development interventions. Major development commitments have been made to the internationally recognized government’s Presidential Leadership Council (PLC). How will accountability for these efforts be put in place to ensure the best possible use of funding for real human development? The political bias of development interventions is starker when looking at available information on Gulf-led development programming, which focuses on their allies in government-controlled priority areas (although with the understanding that development assistance to Houthi-held areas will likely serve as an inducement in any future negotiated settlement). One interviewee stated that the Saudis are the only development partner actually engaging the Houthis, though Saudi development goals are deeply entwined with their political objectives.[69]

Many development narratives remain shallow and not framed within a strategic, country-level analysis of what interventions are likely to have the most impact. One senior humanitarian noted that “we cannot train everyone to be a shepherd or a farmer.”[70] Development interventions in Yemen need to be rooted in a deep understanding of the local economy and culture and based on a realistic assessment of how outside investment can help support sustainable growth.

Development actors continue to struggle to understand and navigate the political context and ramifications of their work. Coordinating and working directly with local actors may be the only available option, but it risks entrenching fragmentation. One interviewee emphasized the need to think beyond the response – protecting development gains and achieving progress where possible, then using these achievements to build confidence between the political parties for de-escalation and agreement. They argued that the response needs to invest in reintegrating fragmented institutions on both sides of the conflict.[71] Development actors are increasingly investing in local governance to get around the political impediments to working at a national level in Yemen. However, this could risk further deepening the political and economic fragmentation of the country. While progressing development activities through local government may be the least bad option in Yemen’s complex operating environment, the political risks of doing so must be taken into account.

Yemeni stakeholders also acknowledged that the lack of a clear economic strategy increased fragmentation. Without a clear strategy, the economy will remain at the mercy of ad hoc interventions. A Yemeni economist noted that “economic activities are happening in Yemen, whether there [is] a strategy or not. The difference is effectiveness and value for money, especially considering that support for Yemen is decreasing significantly.”[72] The private sector is stepping in for the government in many areas, responding to needs in an ad hoc manner and navigating challenges from authorities motivated by political and personal interests. Another interviewee described how the lack of a government strategy to deal with emergency situations allows actors on the ground to get involved with their own programs and agendas.[73]

There is a lack of clear evidence that progress on strategic planning has resulted in effective changes in implementation on the ground. Many initiatives have been lauded as signs of major progress in strategic humanitarian-development coordination, but the impact of these beyond demonstrating an effort to meet strategic imperatives and top-down demands is unclear. Effort needs to be made to ensure efforts result in meaningful changes on the ground.

Humanitarian needs will remain, amid a worsening funding landscape. While many are planning and advocating for a transition away from emergency programming, humanitarian workers, both international and Yemeni, noted that the conflict is ongoing. Humanitarian needs will remain and have the potential to deteriorate. Less money is not always bad. According to an economic analyst working on Yemen, while there has clearly been a reduction in funding, this appears to be driving more critical thinking on how to implement more effective programming.[74] The risk of moving quickly toward development is that direct aid to the most vulnerable communities will be affected as humanitarian resources dwindle.

Civil society leaders interviewed for this report said that they already have less access to funding opportunities compared to national organizations based in Sana’a or Aden. They raised concerns that dwindling funding will see more resources channeled through national-level actors, leaving them to support local communities when international organizations pull out.[75]

Money (and therefore decision-making power) continues to flow through a narrow set of hands. Globally, humanitarian aid is highly centralized through a few major donors and UN agencies. Nearly two-thirds of humanitarian funding in 2022 came from three donors (the US, Germany, and the EU) and went to five – the World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), ICRC, and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).[76] This is also reflected in Yemen, with some local NGOs complaining of monopolization and favoritism by donors and INGOs toward major Yemeni partners, which reduces their ability to compete and build capacity, especially for smaller civil society organizations (CSOs) in remote areas.

Conclusion

New strategies and approaches designed to bridge the humanitarian-development divide and address weaknesses in the pre-2021 aid response are having an impact on the ground in Yemen. Yemeni actors are seeing more sustainable approaches to aid, including longer project timeframes and greater investment in local infrastructure. International actors are making a greater effort to consult local experts.

However, too much of the reform has focused inward. The international aid community’s desire to get its own house in order is understandable, even laudable. But unless the Yemen Partners Group and other key fora can find structures that build Yemeni perspectives into decision-making, they are likely to recreate the disconnect and distrust that characterized the earlier phases of aid distribution. The international community needs to find ways to engage effectively and meaningfully with local actors outside Yemen’s cities.

Yemenis’ long campaign for development funding has been heard. However, development aid will not fix the country. It creates opportunities to better align aid with the building of a sustainable post-war economy, but it also comes with risk. Done badly, development aid could further entrench Yemen’s political and economic fragmentation. Yemenis could find themselves stranded, with humanitarian aid reprioritized to other conflicts and development actors unwilling to invest beyond pilot projects in the absence of a peace deal.

Realistically, Yemen will be in a period of transition for the foreseeable future. The success of the coming phase will depend on how successful Yemenis are in developing a coherent strategy to guide aid investments – both humanitarian and development – and leverage international commitments like the Grand Bargain to wrestle the aid community into living up to its own standards. Success will also depend on whether international aid actors can expand the Yemen Partners Group, or whatever its future iteration may be, to give Yemenis a meaningful seat at the decision-making table, without causing the already unwieldy structure to collapse under its own weight.

In a country like Yemen, with divided governance, insecurity, restrictions on movement, and aid partners scattered around the globe, none of this is easy. However, Yemen, with its deep tradition of mediation, could yet serve as a global model for how to navigate the nexus in fragile states.

Recommendations

- Streamline and operationalize decision-making under the YPG and YPTT to ensure it is more inclusive of Yemeni voices.

- Support Yemeni stakeholders across different authorities to work together to develop a national version of the YPG, focused on less political issues, such as technical coordination on electricity, telecoms, water, and infrastructure. Ensure strong representation of the private sector, local authorities, and CSOs, especially women-led organizations.

- Support Yemeni-led, area-based coordination that oversees both humanitarian and development funding. This should include local government and civil society representatives. It should not approve projects, to avoid slowing down delivery, but rather should i) develop strategies for priority projects in the area covering both humanitarian and development; ii) provide a focal point for donors to engage on local priorities; iii) provide a focal point for communities to provide feedback on program quality; and iv) support implementing organizations to design projects and negotiate access.

- Ensure that aid approaches do not solidify divisions and fragmentation between areas controlled by various warring parties. Where possible, ensure an equitable allocation of both humanitarian and development resources across Yemen.

- Find ways to implement nexus projects at scale where possible taking into account data that indicates current area based pilot nexus interventions are succeeding.

- Ensure donors continue to work towards a coordinated delivery of effective aid in Yemen that aims where possible to proactively engage with shifting developments on the ground.

- Pilot simultaneous and coordinated humanitarian and development programming, rather than seeing one as following the other.

- Explore options to integrate humanitarian, cash, and large-scale social protection programs, beginning with data sharing and interoperability, to ensure the aid response can target people in greatest need.

- Accelerate localization efforts and ensure equitable involvement of Yemeni organizations, both local and national, across the whole program cycle.

- Ensure that at least 25 percent of funding goes to national and local organizations, based on Grand Bargain commitments. Explore waivers for smaller organizations regarding partnership requirements, underpinned by innovative monitoring and oversight processes to guard against corruption. Integrate capacity and institutional building into project funding to raise the capacities and competitiveness of local organizations, particularly in rural areas, to assist them in navigating complex procurement processes. Where possible, extend project implementation periods so organizations have time to learn and properly integrate capacity building into their organizational structures.

- Consider including a budget line to fund the participation of national and local partners in coordination meetings, giving priority to women-led organizations and representatives of local organizations from rural and remote areas.

- Invest in reviving Yemeni accountability and monitoring bodies to increase transparency, including supporting Yemeni development monitoring to take stock and keep track of promised deliverables, supporting independent media in reporting on aid work in the country, and building the capacity of national institutions, including the Central Organization for Control and Accounting (COCA).[77]

This report was produced as part of the Applying Economic Lenses and Local Perspectives to Improve Humanitarian Aid Delivery in Yemen project, funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

- “‘Where is our money?’.. A campaign seeks the fate of 20 billion dollars in international aid to Yemen [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, April 12, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/166832; Sarah Vuylsteke, “When Aid Goes Awry: How the International Humanitarian Response is Failing Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 27, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/reports/humanitarian-aid

- Afrah Nasser, ”The flaws and failures of international aid to Yemen,” Arab Center Washington DC, October 20, 2022, https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-flaws-and-failures-of-international-humanitarian-aid-to-yemen/

- United Nations, “The New Way of Working,” United Nations, https://www.un.org/jsc/content/new-way-working; “The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus Interim Progress Review,” OECD, May 10, 2022, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/the-humanitarian-development-peace-nexus-interim-progress-review_2f620ca5-en

- Sarah Vuylsteke, “When Aid Goes Awry: How the International Humanitarian Response is Failing Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 27, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/reports/humanitarian-aid. Afrah Nasser, ”The flaws and failures of international aid to Yemen,” Arab Center Washington DC, October 20, 2022, https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-flaws-and-failures-of-international-humanitarian-aid-to-yemen/. Lewis Sida et al. “Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Yemen Crisis. “Inter-Agency Standing Committee, July 13, 2022, pp. 120-123, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/inter-agency-humanitarian-evaluation-iahe-yemen-crisis

- Lamis Al-Iryani, Alain de Janvry and Elisabeth Sadoulet, “The Yemen Social Fund for Development: An Effective Community-Based Approach amid Political Instability,” International Peacekeeping, 22:4, 2015, pp. 321-336, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13533312.2015.1064314

- “World Bank halts Yemen activities over security fears,” AFP, March 13, 2023, https://english.alarabiya.net/business/economy/2015/03/13/World-Bank-halts-Yemen-activities-over-security-fears

- “Yemen: highest emergency response level declared for six months,” UNOCHA, July 1, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20150702080509/http://www.unocha.org/top-stories/all-stories/yemen-highest-emergency-response-level-declared-six-months

- “Financial Tracking Service: Yemen 2015,” OCHA, https://fts.unocha.org/countries/248/summary/2015

- Ibid.

- United Nations, “Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan 2023,” OCHA, January 25, 2023, p. 33, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-2023-january-2023-enar

- Paul Harvey, Abby Stoddard, Monica Czwarno, and Meriah-Jo Breckenridge, “Humanitarian Access SCORE Report: Yemen,” CORE, March 2022, p. 7, https://www.humanitarianoutcomes.org/SCORE_Yemen_March_2022; Marzia Montemurro and Karin Wendt, “Principled Humanitarian Programming in Yemen – A Prisoner’s Dilemma?,” HERE-Geneva, December 2021, p. 23, https://here-geneva.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Principled-H-programming-in-Yemen_HERE-Geneva_2021-1.pdf

- Key informant interviews with Yemeni aid actors, April-July 2023.

- Victoria Metcalfe-Hough, et al. “Grand Bargain Annual Independent Report 2022,” Inter-Agency Standing Committee – ODI, June 22, 2022, https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain-official-website/grand-bargain-annual-independent-report-2022; Louise Redvers, The New Humanitarian. “The ‘New Way of Working’: Bridging aid’s funding divide,” The New Humanitarian, June 9, 2017, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2017/06/09/new-way-working-bridging-aid-s-funding-divide; “The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Initiative,” World Bank, March 3, 2017, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/brief/the-humanitarian-development-peace-initiative; “The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus Interim Progress Review,” OECD, May 10, 2022, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/the-humanitarian-development-peace-nexus-interim-progress-review_2f620ca5-en

- Victoria Metcalfe-Hough, et al. “Grand Bargain Annual Independent Report 2022,” Inter-Agency Standing Committee – ODI, June 22, 2022, https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain-official-website/grand-bargain-annual-independent-report-2022

- “The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus Interim Progress Review,” OECD, May 10, 2022, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/the-humanitarian-development-peace-nexus-interim-progress-review_2f620ca5-en

- “Solferino and the International Committee of the Red Cross,” ICRC, June 2010, https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/feature/2010/solferino-feature-240609.htm

- “Development Assistance Committee,” OECD, https://www.oecd.org/dac/development-assistance-committee/

- “The 17 Goals,” UN Sustainable Development Goals, https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- “The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005) and the Accra Agenda for Action (2008),” OECD, https://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/34428351.pdf

- “Financial Tracking Service: Yemen 2015,” OCHA, https://fts.unocha.org/countries/248/summary/2015

- United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework, 2022-2024 (January 2022) https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-06/Yemen-Cooperation_Framework-2022-2024.pdf

- Flexible funding is a core principle of the Good Humanitarian Donorship initiative, agreed in 2003. “24 Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship,” Good Humanitarian Donorship, June 2018, https://www.ghdinitiative.org/ghd/gns/principles-good-practice-of-ghd/principles-good-practice-ghd.html

- Although seasoned humanitarians also pointed out the unrealistic expectation that US$23 billion in humanitarian funding would ‘fix’ a crisis that has cost Yemen well over US$180 billion in lost economic output, according to UNDP. Jonathan D. Moyer. Et al. “Assessing the Impact of War in Yemen on Development in Yemen,” UNDP, April 22, 2019, p. 36, https://www.undp.org/yemen/publications/assesing-impact-war-development-yemen

- “Financial Tracking Service: Yemen 2015,” OCHA, https://fts.unocha.org/countries/248/summary/2015

- Ben Parker and Annie Slemrod, “Exclusive: The biggest Yemen donor nobody has heard of,” The New Humanitarian, March 1, 2021, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2021/3/1/mysterious-new-yemen-relief-fund-aims-to-stop-famine

- Sarah Vuylsteke, “When Aid Goes Awry: How the International Humanitarian Response is Failing Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 27, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/reports/humanitarian-aid

- Marzia Montemurro and Karin Wendt, “Principled Humanitarian Programming in Yemen – A Prisoner’s Dilemma?,” HERE-Geneva, December 2021, p. 27, https://here-geneva.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Principled-H-programming-in-Yemen_HERE-Geneva_2021-1.pdf

- Key informant interviews with Yemeni aid actors, April-July 2023.

- Marzia Montemurro and Karin Wendt, “Principled Humanitarian Programming in Yemen – A Prisoner’s Dilemma?,” HERE-Geneva, December 2021, p. 21, https://here-geneva.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Principled-H-programming-in-Yemen_HERE-Geneva_2021-1.pdf

- The most recognized organizations were WFP, UNICEF, the Social Fund for Development, and Care International. Paul Harvey, Abby Stoddard, Monica Czwarno, and Meriah-Jo Breckenridge, “Humanitarian Access SCORE Report: Yemen,” CORE, March 2022, p. 7, https://www.humanitarianoutcomes.org/SCORE_Yemen_March_2022

- Key informant interviews with Yemeni aid actors, April-July 2023.

- Sarah Vuylsteke, “When Aid Goes Awry: How the International Humanitarian Response is Failing Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 27, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/reports/humanitarian-aid

- Lewis Sida et al. “Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Yemen Crisis. “Inter-Agency Standing Committee, July 13, 2022, pp. 120-123, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/inter-agency-humanitarian-evaluation-iahe-yemen-crisis

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Key informant interviews with international aid actors in Yemen, October 2023.

- “David Gressly Opening Remarks at YIF2023 Opening Session,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies YouTube page, July 17, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6-mPqZxOgP4

- “Iraq Reform, Recovery and Reconstruction Fund (I3RF): Trust Fund Annual Progress Report to Development Partners 2021,” World Bank, April 7, 2021, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/iraq/publication/iraq-reform-recovery-and-reconstruction-fund-i3rf-trust-fund-annual-progress-report-to-development-partners-2021

- “The Yemen International Forum II,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, https://sanaacenter.org/yif/

- Henk Engelberts and Marc Wormmeester, “Damage and Capacity Assessment: Port of Aden and Port of Mukalla,” UNDP, April 26, 2021, https://www.undp.org/yemen/press-releases/importance-yemens-ports

- This includes expanded engagement from actors such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Key informant interviews with international aid experts, September and October 2023

- “Yemen: Huthis suffocating women with requirement for male guardians,” Amnesty International, September 1, 2022, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/09/yemen-huthis-suffocating-women-with-requirement-for-male-guardians/

- Key informant interview with an international aid expert, October 2023.

- Key informant interview with an international aid expert, October 2023.

- Key informant interview with a Yemeni aid expert, July 2023.

- Key informant interview with a Yemeni aid expert, July 2023.

- Key informant interview with an international aid expert, October 2023.

- Key informant interview with a Yemeni development expert, March 2023.

- Key information interviews with Yemeni development experts, March-April 2023.

- Key informant interviews with international aid experts, October 2023; Sarah Vuylsteke, “Revisiting the Sana’a Center’s Humanitarian Aid Reports: Then and Now,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, June 15, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/20355

- Sarah Vuylsteke, “Revisiting the Sana’a Center’s Humanitarian Aid Reports: Then and Now,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, June 15, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/20355

- Key informant interview with an international aid expert, October 2023.

- Key informant interview with an international aid expert, August 2023.

- Key informant interview with an international aid expert, August 2023.

- Key informant interview with an international aid expert, July 2023

- Key informant interviews with Yemeni aid and economy experts, July 2023.

- Key informant interview with an international aid expert, August 2023.

- Key informant interview with an international aid expert, August 2023.

- Key informant interview with a senior aid worker, August 2023.

- Key informant interview with an international donor, September 2023.

- Key informant interview with a senior aid worker, August 2023.

- Sarah Vuylsteke, “Revisiting the Sana’a Center’s Humanitarian Aid Reports: Then and Now,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, June 15, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/20355

- Ibid.

- Key informant interview with an INGO country director, July 2023.

- Key informant interviews with INGO and UN workers, July-September 2023.

- “Red Sea Attacks Provoke International Response – The Yemen Review November and December 2023,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 27, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/nov-dec-2023/21547

- Key informant interview with a senior aid official, August 2023.

- Key informant interviews with Yemeni aid and economy experts, July 2023.

- Key informant interview with a senior international aid worker, August 2023.

- Key informant interview with a senior international aid worker, August 2023.

- Key informant interview with an international aid actor working on Yemen, September 2023.

- Key informant interview with a Yemeni economist, April 2023.

- Key informant interview with a Yemeni businessman and member of the Federation of Yemen Chambers of Commerce and Industry, April 2023.

- Key informant interview with an economic analyst covering Yemen, July 2023.

- Key informant interviews with Yemeni aid actors, July 2023.

- The UN’s Financial Tracking Service recorded US$25.2 billion in funding to WFP, UNICEF, UNHCR, ICRC, and IOM in 2022. Total funding was US$40.5 billion. 25.2/40.5 = 62%. “Financial Tracking Service: Yemen 2022,” OCHA, https://fts.unocha.org/countries/248/summary/2015 https://fts.unocha.org/global-funding/recipients/2022

- For more on the role COCA plays in Yemen, see: Mujahid Muhammad Al-Mu’afa, “The role of the Central Organization for Control and Accounting in Yemen in implementing performance oversight in light of the presence of coercions,” Mohammed V University, Faculty of Khakouk, Souissi, Rabat, Morocco, January 4, 2022, https://www.hnjournal.net/en/3-4-18/

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية