Yemen at a Glance

State of the War

By Abubakr al-Shamahi

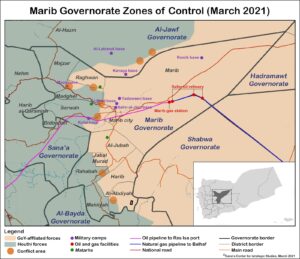

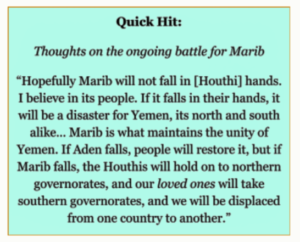

The Battle for Marib

Houthi forces edged closer to Marib city in February, repeatedly firing missiles on the capital of Marib governorate during a fresh push to capture the last major northern city under government control. The fall of Marib city would be a catastrophic blow for the government. It also would compel thousands of civilians – including internally displaced persons (IDPs) who fled their homes earlier in the war and settled in Marib – to leave the city for other areas, in order to escape the conflict. Some IDPs have already left camps in the vicinity of Marib Dam, on the border between Serwah district and Marib city.

The Houthis began their latest push toward Marib city in the first week of February, after sending reinforcements to frontlines in Serwah and Medghel districts. In the second half of 2020, the Houthis appeared to be focused on pushing toward Marib city from the south of the governorate, but government lines in Jabal Murad and Al-Abdiyah districts held relatively well, and tribes in those areas rebuffed Houthi entreaties to either join them or grant them safe passage through tribal territory. The main axis of the Houthi offensive came from the direction of Serwah district, as the Houthis attempted to move east toward Marib city.

Heavy fighting between the Houthis and the internationally recognized Yemeni government, along with its allied tribal forces, took place in Al-Makhdarah area of southern Serwah; Al-Buhayshaa in southeastern Serwah; and Haylan, Adhuf and Al-Mashja’ in eastern Serwah. The fighting has, at the time of writing, resulted in a large number of casualties on both sides and limited Houthi territorial gains in the direction of Marib city.

The most significant success for the Houthis in the current offensive came on February 10, when their fighters entered Kofal base, the headquarters of the Yemeni government’s 312th Armored Brigade, after days of fighting in the surrounding areas. Kofal is approximately 25 kilometers west of Marib city. Houthi forces remain in the base but are far from secure there, as the Yemeni government military has sent reinforcements to the area, including from Shabwa and other government controlled areas, in an effort to retake Kofal. Government forces have retaken some territory surrounding the base, with the backing of Saudi-led coalition airstrikes.

Since the seizure of Kofal, fighting between the Houthis and Yemeni government forces has also expanded to areas hosting IDP camps west of the Marib Dam, approximately 15 kilometers outside the city. These include Al-Sawabeen, Al-Zour and Dhinah, which are home to roughly 30,000 people in total. These camps have not been spared the fighting. The UN reported that 8,000 people have been displaced as a result of recent fighting in Marib, from both towns and camps.

As February drew to a close, it appeared the Houthi offensive was running out of steam, at least for the time being. Yemeni government forces are treating the battle for Marib city as an existential threat and have established strong defensive lines between the city and Kofal, making it more difficult for the Houthis to advance farther. It wasn’t yet clear whether the Houthis would attempt to secure Kofal base and use it as a staging point for new offensives while continuing to fire missiles at Marib city. The city has become increasingly vulnerable to aerial attacks as the Houthis edge closer. It can no longer rely on the defensive capabilities provided by the UAE’s patriot missile batteries, which were withdrawn in June 2019. (For further analysis on the battle for Marib, see ‘Marib and the Closing Bell of the Yemen War’ and ‘Washington’s Lack of Options in Marib’)

Other Frontlines

The fight for Marib consumed attention in February, and both the Houthis and the Yemeni government moved forces to the governorate from other areas of the country. This had the knock-on effect of reducing hostilities on frontlines elsewhere – for instance, in Hudaydah and Taiz.

In Hudaydah city, shelling of a wedding hall on January 1 left three civilians dead, according to the UN. Some of the victims were reportedly children. The Houthis and the Joint Forces, which are led by Tareq Saleh and backed by the Saudi-led coalition, each claimed that the other side was responsible for the attack, but local residents told the Sana’a Center that the shell was fired from the direction of territory controlled by the Houthis.

Heavy fighting throughout January in Hudaydah city, as well as in the districts of Al-Durayhimi, Hays and Al-Tuhayta, left dozens of fighters dead on both sides, without any major territorial advances. By February, the Houthis began withdrawing some of their forces from the governorate, most likely to redeploy them to frontlines in Marib. Houthi operations in Hudaydah subsequently focused on erecting barricades, launching reconnaissance drones and moving heavy weapons to new locations in preparation for future rounds of fighting.

In northeastern Taiz governorate, fighting broke out in early January between the Houthis and local residents in the Houthi-controlled area of Al-Haymah. Houthi forces had attempted to detain a resident of the village of Al-Sayilah, whom they accused of working with the Yemeni government. The man, Abdullah Al-Radhi, fought back. He was supported by villagers, leading to a week of fighting and casualties on both sides. The Houthis quickly ended the uprising and, at the end of February, about 300 locals remained detained in a prison in Hawban, on the outskirts of Taiz city, according to a member of the local mediation committee.

Cross-Border Attacks

The Houthis carried out a number of cross-border aerial attacks on Saudi Arabia in the first two months of the year. While the majority of Houthi projectiles were intercepted, some did get through. Most notably, a February 10 attack on Abha Airport in southern Saudi Arabia set fire to a civilian aircraft. Separately, on January 17, a projectile fired by the Houthis injured three Saudi civilians in a border village in Jizan province.

The Houthis continued their barrage toward Saudi Arabia in the latter part of February, and on February 27 the Saudi-led coalition said that it had intercepted one missile over Riyadh, as well as six armored drones targeting southern cities such as Khamis Mushait and Jizan. For their part, the Houthis said that its forces had fired a ballistic missile and 15 armored drones at Saudi Arabia.

Abyan

The former Shoqra frontline between Yemeni government and Southern Transitional Council (STC) forces in Abyan remained quiet in January and February, after both sides withdrew their forces in December. The Giants Brigades, an Emirati-backed force supported by the Saudi-led coalition, currently patrol Shoqra as a neutral force. Both the Yemeni government and the STC continue to demand that each other’s forces stationed elsewhere in Abyan be redeployed, per the terms of the Riyadh Agreement.

The Political Arena

Developments in Government-Controlled Territory

New Security Chief Appointed in Aden

On January 3, Aden’s director of security for the past five years, General Shalal Ali Shayea, transferred the administration of Aden’s security to General Mutahar al-Shouaibi, as part of the Riyadh Agreement. President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi named Ahmed al-Hamidi to the post in late July, but he was not prepared to travel from Riyadh to Aden for the handover of power, as Shayea had insisted. There were also questions about whether Al-Hamidi could effectively secure the loyalty of the forces. Al-Shouaibi, who is known for his affiliation with the General People’s Congress party, and Shayea are from the same area of Al-Dhalea governorate, a secessionist stronghold from which many senior leaders of the Southern Transitional Council (STC) hail, including its top political leader, Aiderous al-Zubaidi. Shayea was offered the post of military attache in Yemen’s embassy in the UAE, but he refused the assignment and is currently in southern Yemen.

Reunified GCC Backs Yemen’s Internationally Recognized Government

All six leaders of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) gathered in Riyadh for the council’s annual summit for the first time since Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates (as well as Egypt, a non-GCC member) severed diplomatic relations with Qatar and imposed an economic blockade in mid-2017. At the time, the blockading countries accused Doha of supporting the Houthis and the Muslim Brotherhood in Yemen. Qatar subsequently withdrew from the Saudi-led military coalition and ended financial assistance to the Hadi government. The impacts of the GCC reconciliation for Yemen are yet to be seen. The internationally recognized Hadi government, the Houthis and the STC expressed support for the Saudi-Qatari reconciliation in tweets.

UN Envoy Travels to Aden

On January 7, the UN special envoy to Yemen, Martin Griffiths, traveled to Aden to hold meetings with the newly-formed government that was targeted in a December 30 missile attack at Aden airport. Griffiths surveyed the damage from the missile attacks, which killed at least 28 people and wounded more than 110. He met with Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed, who said that the attacks sought to “eliminate” the cabinet. In remarks to the UN Security Council on January 14, Griffiths noted that the government had completed an investigation and concluded that the armed Houthi movement was behind the attacks.

STC Leader Reaffirms Secession Goal

STC President Aiderous al-Zubaidi said in an interview with UAE-based SkyNews Arabia that the secessionist group still plans to form an independent state of South Yemen. The remarks came nearly a week after the power-sharing cabinet of Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek arrived in Aden as per the terms of the Riyadh Agreement, in which the STC agreed to incorporate politically and militarily into government institutions. Al-Zubaidi, who currently lives in Abu Dhabi, said that the only way to achieve peace and stability in Yemen was through the creation of an independent state in southern Yemen, as existed prior to 1990.

Cracks Emerge in Aden’s Power-Sharing Government

In mid-January, President Hadi signed presidential decrees appointing former Prime Minister Ahmed Obaid bin Dagher as chairman of the Shura Council and Ahmed Ahmed Saleh Al-Mousai as public prosecutor. STC leaders rejected the “unilateral” appointments and accused Hadi of trying to derail the Riyadh Agreement. The Socialist and Nasserist political parties in Aden joined the STC’s condemnation.

Critics of the appointments said they went against the spirit of power-sharing laid out in the Riyadh Agreement. The STC is particularly opposed to the appointment of Bin Dagher, with whom it clashed repeatedly during his tenure as prime minister. The STC has threatened “appropriate steps” if the appointments are not reversed, including a return to self-rule in southern Yemen, which the separatist group announced in April 2020 before abandoning that plan in July.

STC Meets with Russian Foreign Ministry

In early February, Al-Zubaidi and a high-level delegation of STC officials, including Aden Governor Ahmed Lamlas, held several days of meetings with officials at the Russian Foreign Affairs Ministry in Moscow. The visit came about a month after the formation of a tenuous power-sharing government in Aden between the STC and Yemen’s internationally recognized government as part of the Saudi-brokered Riyadh Agreement. During the Moscow visit, Al-Zubaidi told Russia Today in an interview that the Riyadh Agreement was a transitional phase before the formation of an independent southern state resembling the former South Yemen, which had strong ties with the former Soviet Union until its collapse in 1989. It was the STC’s second official visit to Moscow since March 2019. The Hadi government has also conducted outreach to the Kremlin; in December 2020, Ahmed al-Essi, a close associate of the Yemeni president and powerful oil trader in the south, visited Moscow as head of the Southern National Coalition, which was formed in May 2018 to rival the STC. In an interview with Sputnik, Al-Essi insisted Russia supports a unified Yemen. (See ‘Businessmen are not prohibited from engaging in politics’ – A Q&A with Ahmad al-Essi)

Hadrami Tribal Alliance Urges Hadi to Declare Hadramawt a Federal Region

On February 3, the Hadrami Tribal Alliance called on President Hadi to declare Hadramawt a separate region, in line with the federal state structure envisioned in the outcomes of the National Dialogue Conference, which concluded in 2014. The Hadramawt region would include the governorates of Shabwa, Al-Mahra and the Socotra archipelago. All four of these governorates are part of the former South Yemen, which the Aden-based STC seeks to revive as an independent state at some point in the future. The separatist political bloc rejects the idea of a federal, unified state structure in particular and the NDC outcomes in general. These issues represent some of many sticking points between the internationally recognized government and the STC, which formed a power-sharing government in December as part of the Saudi-brokered Riyadh Agreement.

The Stockholm Agreement

Prisoner Exchange Talks End Without a Deal

On February 21, the UN special envoy to Yemen, Martin Griffiths, announced that the latest round of negotiations between Yemen’s internationally recognized government and the Houthis to secure the release of thousands of Yemenis imprisoned during the war ended without a deal. The prisoner swap is one of the major components of the 2018 Stockholm Agreement that halted a UAE-backed military offensive aimed at capturing the Red Sea port city of Hudaydah from the Houthis. The largest prisoner release to-date stemming from the deal agreed to in Sweden occurred in October 2020, when nearly 1,100 prisoners were exchanged. However, that deal was skewed significantly in the Houthis’ favor: Most of the 400 individuals the Houthis released were civilians, including five journalists, in exchange for 681 Houthi fighters, some of whom were reportedly on the frontlines shortly after they returned to Yemen.

Growing Calls for the Government to Withdraw from Stockholm Agreement

On February 10, Tareq Saleh, nephew of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh and commander of the anti-Houthi National Resistance Forces that led the 2018 military campaign to capture Hudaydah, called on the Hadi government to withdraw from the UN-brokered Stockholm Agreement. In a tweet, Saleh, who is close to the UAE, rallied anti-Houthi forces to fight as one in Hudaydah and in Marib, where Houthi forces have renewed their bid to capture the northern governorate.

On February 13, a group of MPs in the internationally recognized government urged it to withdraw from the Stockholm Agreement. In a letter addressed to President Hadi, Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar and Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed, the MPs argued that the Houthis have not only failed to comply with the agreement, but used it as an opportunity to open new battlefronts, namely, in Al-Jawf and Marib, where stop-start fighting has entered its thirteenth consecutive month.

Developments in Houthi-Controlled Territory

Houthis Release Circular Banning Online Events

The Houthi-run Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (SCMCHA) ordered local non-governmental organizations operating in Houthi-controlled areas to seek permission before holding or participating in online activities, such as Zoom internet calls. SCMCHA has issued a number of restrictions on humanitarian organizations since the council was formed in November 2019.

Court Resumes Prosecution of Baha’i Religious Minority

On January 9, the Houthi-run Specialized Criminal Court in Sana’a resumed proceedings against 24 members of the Baha’i religious minority, despite a decree by Supreme Political Council President Mahdi al-Mashat dropping the charges in late March 2020.

In late July 2020, six Baha’is (five of whom are part of the 24 being prosecuted) were released from prison in Sana’a and sent into exile in Luxembourg. The 19 Baha’is on trial who remain in Yemen have gone into hiding out of fear of being imprisoned without due process.

On February 13, the Specialized Criminal Court held the latest hearing of the ongoing case against the 19 Baha’is. At the hearing, the court sidestepped the March 2020 decision and returned the case to the prosecution to continue pursuing criminal charges. The Baha’i community interpreted the ruling as an attempt by Houthi authorities to confiscate the remaining assets of the 24 defendants. The Houthi government has frozen the bank accounts of the Baha’is and seized some of their real estate and assets. The confiscations and frozen bank accounts remain in effect, despite Al-Mashat’s action nearly a year ago.

Authorities in Sana’a Police Gender Roles and Women’s Rights

On January 20, Houthi officials stormed women’s clothing stores in the capital Sana’a and broke mannequins on display, claiming they violated Islamic conduct, corrupted society and propagated vice and nudity. Merchants were fined after their mannequins were destroyed. Amid the crackdown on women’s clothing stores, Houthi authorities from the Sana’a mayor’s office closed Rainbow restaurant in Haddah neighborhood, alleging it promoted homosexuality. Later in the month, the Houthi-run Ministry of Health and Population banned the use of birth control, while Friday sermons in a number of mosques in Sana’a and other Houthi-controlled areas said that it was only permissible for women to work in girls’ schools or women’s hospitals.

Houthis Delay Inspection of FSO Safer Oil Tanker

On February 2, UN officials announced the delay of a planned inspection and repair mission to the FSO Safer oil tanker moored in Houthi-controlled waters off of Hudaydah. In the absence of written security guarantees from the Houthis, the UN said it was forced to call off the mission, which Houthi authorities agreed to in November 2020 and was supposed to take place in the first week of February.

The Houthis have repeatedly prevented technical teams from taking steps to safely offload the 1.1 million barrels of oil aboard the 45-year-old vessel amid concerns that a potential spill could cause an unprecedented environmental disaster in the Red Sea. Houthi officials advised the UN in early February to pause certain preparations for the inspection mission pending the outcome of a review of the formal approval. On February 24, Stéphane Dujarric, spokesman for the UN Secretary-General, announced that the Houthis had made additional requests focused on “logistics and security arrangements,” adding that “it’s now difficult to say exactly when the mission could be deployed.”

International Developments

US State Department Labels Houthis a Terrorist Group — Briefly

For less than a month, the United States designated the armed Houthi movement, Ansar Allah, as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) — one of the last decisions by the Trump administration and one of the first big foreign policy reversals enacted by the incoming Biden team. On January 19, outgoing US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo designated the armed Houthi movement as an FTO and a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) entity. Three senior Houthi officials were also designated as SDGTs: top leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi; Abd al-Khaliq Badr al-Din al-Houthi, the youngest brother of Abdelmalek and military commander of the Houthi movement who also heads the group’s elite Republican Guards and special forces units; and Abdullah Yahya al-Hakim (aka “Abu Ali”), a key military leader who oversees the Houthi intelligence apparatus. Abd al-Khaliq al-Houthi and Abdullah Yahya al-Hakim were sanctioned by the US Treasury Department in 2014, and Abdelmalek al-Houthi was sanctioned by the UN in 2015. The Biden administration reversed the terrorist designation of the group as a whole on February 5, following concern from the UN, Western donor countries, international aid agencies and analysts that the FTO designation risked large-scale famine by preventing the entry of humanitarian aid and commercial imports.

Biden Administration Prioritizes Diplomacy in Yemen

On February 4, President Joe Biden announced the end of US support for offensive Saudi military operations in Yemen and appointed vetarn diplomat Tim Lenderking as the US special envoy to Yemen. The announcements marked a significant shift in US policy toward Yemen with an emphasis on diplomacy to end the six-year civil war fueled by regional powers including Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran. The Houthis did not reciprocate the de-escalation gestures, instead launching a renewed offensive to seize oil and gas-rich Marib governorate. (See the ‘State of the War’ for more on the Battle for Marib).

On February 26, Lenderking reportedly met the Houthis’ chief negotiator Mohammed Abdel Salam for direct talks in the Omani capital Muscat. “Two sources familiar with the matter” told Reuters that the US envoy pressed the Houthis during the meeting to halt its offensive on Marib and hold virtual talks with Saudi Arabia on a cease-fire. One of the sources said the meeting was part of a new “carrot and stick” approach by the Biden administration, involving diplomatic outreach on the one hand and targeted sanctions on the other. Abdel Salam told the Russian news outlet Sputnik that the Houthi delegation did not meet directly with US officials in Muscat, but rather communicated with the Americans through Omani officials.

Iranian Official Declares Yemen Extension of Islamic Revolution

On February 9, in the first days of the Houthis’ renewed military offensive in Marib, Iran’s ambassador to the Houthi-run government in Sana’a, Hasan Irlu, said in a Twitter post that Yemen’s war was an extension of the Iranian Islamic revolution. The Houthis have long denied such claims, but there was no pushback from the Twitter accounts of senior Houthi leaders.

More Houthi Figures Added to UN, US Sanctions Lists

On February 25, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) designated Houthi official Sultan Zabin for sanctions for engaging in “acts that threaten the peace, security and stability of Yemen, including violations of applicable international humanitarian law and human rights abuses in Yemen.” As director of the Houthi-run Criminal Investigation Department (CID) in Sana’a, Zabin oversaw the establishment of a network of detention centers in which women who opposed Houthi rule, “including at least one minor, were forcibly disappeared, repeatedly interrogated, raped, tortured, denied timely medical treatment and subjected to forced labor.” Zabin personally tortured some of the victims, according to the designation. The last time Yemeni individuals were sanctioned by the UNSC was in 2015.

On March 2, the US Department of Treasury’s Office for Foreign Assets Control added Houthi military leaders Mansur al-Sa’adi and Ahmad ‘Ali Ahsan al-Hamzi to its sanctions list. Al-Sa’adi, who serves as chief of staff of the Houthi Naval Forces, “masterminded lethal attacks against international shipping in the Red Sea,” according to the designation announcement, which noted that these forces have repeatedly dispersed naval mines that strike civilian and military vessels. Major General Al-Hamzi commands the Houthi Air Force and Air Defense Forces, as well as its drone program. Both Al-Sa’adi and Al-Hamzi have received training in Iran and funneled weapons from Iran into Yemen’s civil war, according to the Treasury Department.

Economic Updates

In Yemeni Government-Controlled Territory

UN Report Accuses CBY-Aden of Embezzling US$423 million

The United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen submitted its annual report to the UN Security Council on January 25, which detailed, among a wide spectrum of other issues, the panel’s findings related economic developments in Yemen in 2020. The panel concluded that both the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the Houthi de facto authorities had illicitly diverted the country’s economic and financial resources to serve their own ends, thereby deepening the plight of millions of Yemenis already facing one of the largest humanitarian crises of the modern era.

The report’s most controversial findings, however, related to its accusations that the government-affiliated Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Aden had embezzled US$423 million from a US$2 billion deposit Saudi Arabia made to the CBY-Aden in early 2018 for the purpose of financing basic commodity imports and stabilizing the Yemeni rial (YR) exchange rate. The Panel of Experts report asserted that the CBY-Aden facilitated funds being siphoned off of the Saudi deposit through a mechanism that offered commercial importers a preferential exchange rate on letters of credit (LCs). Of these traders, the Panel of Experts said the Hayel Saeed Anam (HSA) Group, Yemen’s largest business conglomerate and one that holds significant sway with the government, benefited by US$194.2 million, or roughly half of the funds the panel says were embezzled, “excluding profits generated from the import and sale of commodities”. Both the Yemeni government and HSA have vehemently denied the accusations.

Expert analysis of the Panel of Experts’ assessment, however, found significant flaws in both their evidence and arguments (for details see ‘The Panel of Experts Err on Yemen’).

Government Appoints Ernst & Young for External Audit

On February 7, Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed announced that Ernst & Young will conduct an external audit of the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Aden financial statements. The decision arrived in the wake of allegations from the UN Panel of Experts related to the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Aden. Ernst & Young submitted an external audit proposal to the government in March 2019. It remains to be seen whether the Panel of Experts report will prompt further actions from the government, such as a change to the board of directors of the CBY-Aden, which in accordance with CBY legislation was supposed to occur in September 2020.

Yemeni Rial Depreciates in Government Areas after Temporary Improvement

During the months of January and February, the value of the Yemeni rial (YR) in areas nominally under the government’s control steadily depreciated from YR691 per US$1 on January 2 to YR870 per US$1 on February 28. The downward trend was largely expected as the initial market reaction to the formation of a new government in December was always likely to be short-lived.

Following President Hadi’s announcement of a power-sharing government on December 18, the Yemeni rial appreciated to YR643 per US$1 on December 27, a notable improvement from the record low of YR917.5 per US$1 on December 9. In the absence of either increased revenues, external financial support, or increased access to foreign currency circulating through the economy, the value of the Yemeni rial in areas nominally under government control will continue to drop. And as a result, the divergence between the two different exchange rates (and effectively two different currencies) in Yemen will widen – with the value of the Yemeni rial in Houthi-controlled areas remaining relatively stable around YR600 per US$1.

First Fuel Shipment Arrives to Qana, Shabwa

On January 16, the first fuel shipment arrived at Qana, a stretch of coastline located in Radoum district, Shabwa governorate, 20km east of the Balhaf liquified natural gas (LNG) export terminal. The inaugural shipment was a vessel carrying an estimated 17,000 metric tons (MT) of diesel that was then transferred from the vessel via a pipeline to fuel trucks waiting onshore.

According to local media reports, prominent businessman Ahmed al-Essi imported the inaugural shipment under the name of UAE-based company QZY Trading LLC. According to reports in November 2020, Al-Essi may also have been involved in the development of the unloading site onshore. A close confidant of President Hadi operating as deputy director of the Presidential Office for Economic Affairs, Al-Essi held a near monopoly over fuel imports via Aden from July 2015 till June 2020. The notable exception was the period from October 2018 till March 2019, when Saudi Arabia imported fuel as part of a US$180 million fuel for electricity grant it provided to the government. (See the Sana’a Center’s interview with Al-Essi).

Developments in Houthi-Controlled Territory

Renewed and Prolonged Hudaydah Fuel Import Standoff

The latest in a growing list of Hudaydah fuel import standoffs started in January and February and continued into March. The government stopped issuing clearances to fuel vessels looking to proceed from the Coalition Holding Area (CHA) to Hudaydah port, with the exception of one liquified petroleum gas (LPG) shipment that berthed at the Red Sea port in January. Meanwhile, the Houthis reverted to rationing available fuel supplies. The amount of fuel that consumers could purchase at Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC)-run fuel stations was restricted to 30 liters every six days.

There was also a notable spike in fuel prices during January and February. While the ‘official price’ remained YR5,900 per 20 liters, the parallel or informal market price increased – with fuel prices fluctuating between YR12,000-15,000 per 20 liters in January and then peaking at around YR17,000-20,000 in mid-February. Fuel prices reduced slightly by the end of February to around YR14,000 per 20 liters.

Feature

‘Businessmen are not prohibited from engaging in politics’

– A Q&A with Ahmad al-Essi

Officially, Ahmad al-Essi is a businessman who dabbles in politics – he’s the chairman of the Alessi Group as well as the deputy head of Yemen’s presidential office. Unofficially, Al-Essi may be the most powerful Yemeni alive. Certainly, he’s one of the richest.

Twice, once in 2015 and again in 2016, he provided a financial lifeline to President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi – the first time just after Hadi fled Sana’a for Aden, the second after Hadi fired Prime Minister Khaled Bahah and, incensed, the Saudis had cut off Hadi credit. Al-Essi and Hadi had been close for years, dating back to the early 1990s when Hadi was Minister of Defense.

Al-Essi also leveraged his close relationship with the president and his sons to further his business empire, securing a monopoly on fuel imports into Aden. Like Jeff Bezos and Amazon, Al-Essi can supply almost everyone with almost anything. He has sold food and fuel to Saudi and Emirati troops in Yemen, helped keep the Yemeni army and government afloat, and collected a thousand and one favors along the way.

His home, an apartment in Cairo, is the fixed center of the Yemeni universe. Former prime ministers, tribal sheikhs, businessmen, members of parliament and military officers all patiently wait for their audience. Each appointment is written on a single piece of paper in Al-Essi’s own hand.

In January, Al-Essi graciously invited the Sana’a Center to his home for a candid and expansive interview that explored a wide range of topics, including: Al-Essi’s recent visit to Moscow; his Southern ‘unionist’ project; the Houthi takeover’s impact on his business empire and how this empire also props up the Yemeni government; his feud with Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek; how Abu Dhabi will do business with him but still wants him dead, and why he should be Yemen’s next president.

Editor’s Note: The following transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Talking Politics and Oil in Moscow

Sana’a Center (SC): First of all, I would like to thank you, Sheikh Ahmad al-Essi, as I think this is your first interview in a while now. Let me begin with your recent visit to Moscow, what were you doing there?

Al-Essi: The aim of this visit was to start relations and [expand] new horizons for the Southern National Coalition. (The SNC is a southern-based political organization Al-Essi helped found in May 2018. )

At the same time, it was in response to others’ (the Southern Transitional Council) visits to Moscow. We saw that the legitimate government is trapped and we wanted to open relations, at least for the SNC.

In the past, we have met with officials from the American and British embassies, and we clarified the SNC’s position to them. We prefer to also have a presence in Russia as well. Thank God, the visit was positive, and we met with Russian officials.

SC: What do you think of the Russian stance towards Yemen? Is it different from the British and American stances?

Al-Essi: Different. This is what I’ve noticed from my meeting with the deputy foreign minister and the president’s special advisor Mikhail Bogdanov.

SC: The Russian president’s special envoy to the Middle East and North Africa?

Al-Essi: Yes, we spoke to him about the situation in Yemen, and based on his remarks, we saw that Moscow has taken an interest. Frankly, his remarks impressed me. He said that Russia does not stand with the Houthi movement in terms of controlling Yemen, especially its expansion toward the south – hence [it seems] they are focusing on the country’s south – but at the same time, Russia does not stand with Operation Decisive Storm or with the Saudi-led Arab Coalition. Bogdanov said [Russia] was in favor of Yemenis reaching an agreement.

SC: Did you have any commercial relations with Russia before or do you now?

Al-Essi: During this visit, we focused on the issue of the SNC and on our commercial work that pertains to importing petroleum derivatives.

SC: So, there was no import of petroleum derivatives from Russia in the past?

Al-Essi: No, never, and there isn’t now as well.

SC: But would this possibly happen [one day]?

Al-Essi: It’s possible of course because the Russian prices are good. However, importing Russian fuel is difficult. We’ve heard talk about a free market, competitive prices, brokerage companies for years; however, even the last step [toward this end] did not yield results. That’s when we went to their front door, which is the national oil company (Rosneft), and held a simple meeting. [After we left], they made promises, which was a sign that they are interested in this. We will make a second visit.

SNC vs STC: Al-Essi’s ‘Unionist’ Struggle in the South

SC: I would like to talk about the SNC. What do you think of the viewpoint that the SNC was only formed to oppose the STC, and more importantly that the SNC has failed so far at infiltrating, for example, Al-Dhalea governorate, as its activities there are few and its presence is almost nil. It’s said this is evidence that the SNC is essentially directed against a specific geography and that it is incapable of [including] larger political representation, or even larger southern representation. What do you say?

Al-Essi: The establishment of the STC was one of the main reasons behind the formation of the SNC, but it’s not as you said: we are not only against the STC. After liberating southern governorates [from Houthi forces in 2015], we noticed that we have gone back to the totalitarian pattern which the Socialist Party had [adopted] to govern South Yemen and which former President Ali Abdullah Saleh solidified a part of under the pretense of controlling and maintaining unity. The STC only works with one party or one power and the rest do not have an opinion. The presence of political parties, the General People’s Congress (GPC), Islah, the Nasserists and all other parties in southern governorates appeared timid and invisible, and they cannot organize any activity, like it’s some sort of surrender to the STC.

We are from among the southerners, we call ourselves the unionists, and we stand with greater Yemen. Hence, we took an initiative in this regard based on our influence and presence in the southern arena – though at the beginning they used to tell me I wasn’t a southerner – to agree with 13 political parties, including the GPC, Islah, the Baath, the Nasserists – the Nasserist organization eventually withdrew though – Al-Nahda party and components from the Southern Hirak and the Hadramawt Inclusive Conference – and these are the majority of southern components – to be a strong bloc that confronts the STC or those seeking the separation of south Yemen in general. The bloc was formed, and we were going to organize an event to declare establishing it in Egypt’s capital, Cairo.

SC: Why wasn’t it organized in Cairo? Do you think Egyptian authorities refused to let you hold the ceremony at the UAE’s behest?

Al-Essi: The Egyptian authorities gave us all the permits and approvals but our loved ones, the Emiratis, eventually intervened and thwarted the ceremony. The Egyptians then suspended the permits, citing the Egyptian ministry of foreign affairs, even though they had already given us approval.

So we announced the SNC from Aden. It was the first political event to be officially held in the city that wasn’t affiliated with the STC. A large crowd attended. Declaring the formation of the SNC from Aden, and not anywhere else, was proof of our strength, although some of our close allies stood against us.

We were going to hold ceremonies and events in other governorates, as the SNC has a branch in Al-Dhalea and three members of the SNC’s supreme council actually hail from the governorate. The SNC is not regionalist but it’s with Yemeni unity, specifically the unity of southern governorates. However, the battles that erupted in mid-August 2019 (between forces loyal to the government and UAE-backed STC forces and which ended with the latter’s control over the city of Aden and a number of southern governorates) resulted in many difficulties that obstructed our activity in Aden. We were ready in Lahij governorate but we were advised by you know who (i.e. the Saudis) to stop. The special messages to Shabwa, Abyan and Hadramawt governorates were delivered (i.e. the SNC organized public events in all three governorates). In Al-Mahra governorate, there was escalation of revolutionary violence against the kingdom, so the SNC’s command there told us that any event we want to organize is allowed but it would be viewed as against the Coalition and particularly against Saudi Arabia, and they advised not to incite the enmity of the Saudis; hence, we halted organizing any event.

The Impracticalities of the Riyadh Agreement

SC: What do you think of the Riyadh Agreement?

Al-Essi: It’s a good and excellent agreement, but its items and how it was dealt with are as you know…

SC: How?

Al-Essi: Impractical, all about appeasement.

SC: And the new cabinet that was formed under the Riyadh Agreement? What do you think of it?

Al-Essi: The cabinet has been formed, but the Riyadh Agreement does not meet the aspirations in general and it was not implemented. Only what’s in the STC’s interest was implemented. As for the national interest or the legitimate government’s interest, only a little has been implemented.

SC: What if we assume that they assign new governors in Shabwa, Hadramawt and the rest of the south’s governorates (as per the Riyadh agreement)?

Al-Essi: The basis of the Agreement was not implemented. The first point stipulated the return of the Presidential Protection Brigades to their positions in the city of Aden and implementing the security and military aspects [of the deal], but this hasn’t been implemented yet. The only thing implemented was forming a cabinet while the rest of the aspects haven’t been implemented, although the Riyadh Agreement undermined ‘the Legitimacy’.

Businesses in Northern Yemen ‘Suspended’ as Houthis Corralled the Fuel Trade

SC: Allow me to diverge a bit from the Riyadh Agreement. Let’s assume that we wake up tomorrow to witness Yemen divided into two Yemens, what would this mean for your business?

Al-Essi: My business? If I am to think about my business, I’d work with the Houthi movement, the STC and the legitimate government. The picture is clear. All merchants work in all three areas, the merchants in the north and in the south work in all areas. I am the only one who took a clear stance toward the Houthis. All my capital and economic capabilities in the city of Hudaydah and the capital Sana’a (both are under the Houthis’ control) are taken. Business is important, but the situation we’ve reached with the Houthis was impossible.

SC: But according to my information, your business is on, and even the oil that funds the Houthis goes through you.

Al-Essi: No, dear, I challenge anyone to prove this. I haven’t had any commercial activity in Houthi-controlled governorates since the first day of Decisive Storm Operation [in March 2015]. My business has been suspended as the Houthis seized some property like houses and land in Sana’a, and a hospital, and closed the headquarters of my companies and factories and Al-Shifa medical college in the city of Hudaydah.

SC: This means that you do not have any current investments in Houthi-controlled areas?

Al-Essi: What I have now is my charitable work, and the payments made to employees who have been home since 2015 and up until today.

SC: How do the Houthis get their fuel supplies, then?

Al-Essi: Through the port in the city of Hudaydah, through the merchants they created. At the beginning, Tawfiq Abdelraheem helped them but they imprisoned him because they believed he opposed them, and currently, their merchants provide the fuel.

Before the war erupted, only myself and Tawfiq Abdelraheem worked in the oil sector. Currently, however, everyone is engaged in business in sectors that are not their specialty, like [Ahmed] Al-Muqbali (the largest fuel importer to Hudayah), for example, worked in the field of automotive spare parts but then shifted to oil trade.

SC: And all this happens with the knowledge of the government and the Coalition and goes through the procedures to attain licenses?

Al-Essi: Yes, hence violating the measures they have imposed.

SC: Who imposed them?

Al-Essi: The Coalition and the United Nations. In the beginning, oil supplies to the Houthis were only permitted via the government-controlled governorates, like Aden, but in the end they could not control this because the prime minister used to issue exceptional directives every year under which oil ships were allowed in.

Then they reached the agreement to implement the system of the economic committee which stipulated paying taxes and customs to the Central Bank in Aden, but they later agreed to pay them to the Central Bank in Hudaydah.

The goods that are brought in through the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism, on condition that they do not come from Iran, are sold to the Houthis as well as in government-controlled areas on condition that taxes and customs are paid to an account in the Central Bank in Hudaydah. This account covers the salaries of some government employees and the rest of the salaries are paid by the Yemeni government. The government did in fact pay the salaries of employees at the ministries of education, health, etc. The sum of the money in the account at the Central Bank [in Hudaydah] reached around 38 billion Yemeni rials. The Houthis, however, violated the procedures that allowed them to bring in fuel so the Coalition prevented any ship carrying oil from entering the port of Hudaydah (leading to the June 2019 fuel crisis).

Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek is ‘Accountable for Corruption’

SC: Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek says his battle with you is a battle against corruption.

Al-Essi: He must prove what he’s saying. He is the PM, he says I am corrupt and everything is in my hands, the oil is in my hands. He must prove this. Our disagreement with Maeen is not because he is a prime minister or because he is delinquent but because he is a merchant; hence we hold him accountable for a part of this corruption.

SC: How?

Al-Essi: He is associated with trade groups, and he previously…[actually], I’ll hold on to this piece of information for now.

SC: No, you can’t. You can’t give me half info and expect me to treat it seriously. Can you share more?

Al-Essi: He is officially associated with Al-Saghir Sons (a contracting company Maeen worked with in the past), Hayel Group (The Hayel Saeed Anam & Co) and Shehab (Shehab Trading & Investment Corporation), and he was engaged with them as a partner in an investment project in Ethiopia and other businesses and contracting projects. He is also associated with other large business groups. He facilitates their work and harnesses all the state support to help them. All these businesses pay their taxes to the Houthi movement, though they are given priority in terms of benefiting from the legitimate government’s and the Coalition’s capabilities.

You work with the Houthis, and I work with the Legitimacy. Your loyalty and revenues are for the Houthis while my loyalty and revenues are for the legitimate government. With Maeen, issues are facilitated for you and you are granted wider jurisdictions.

SC: Hayel, do you mean The Hayel Saeed Anam & Co?

Al-Essi: I am not talking about a specific group but about Maeen Abdelmalek and his policies. Hayel Saeed, Fahem (Haidar Fahem, a top importer of wheat), Thabet (Thabet Group) as well as other merchants have benefitted from these policies. The problem isn’t in the merchant but in the official who is also a merchant.

Patron to President Hadi, Keeping the Economy Well Oiled

SC: You speak about Maeen as if he is a dubious figure, but don’t you think that you have some sort of conflict of interest? What I mean here, is Ahmad al-Essi a sheikh, an oil merchant, the deputy director of the president’s office, an athlete (Al-Essi is president of the Yemeni Football Association) or the leader of a political party?

Al-Essi: This runs in our system. Businessmen are not prohibited from engaging in politics. Politics was imposed on us – we did not shift from being politicians to becoming businessmen; it’s actually vice versa. This is due to exceptional circumstances. The politicians we relied on were losers. After we left Hudaydah due to battles [in 2015] and reached Aden, there weren’t any politicians or officials there. Are they agents? Are they weak? Have they escaped? I didn’t know at the time.

The national cause demanded that we engage in politics. We do not perform official work and we do not set recommendations or issue directions at the presidential office.

SC: But you have an official position.

Al-Essi: An honorary one. I don’t issue directions or make decisions. We helped the government at the beginning when it arrived in Aden. We cooperated with it and prepared everything, and they owe us money to this day.

SC: Do you mean the one billion [Yemeni rials] that you saved the president with when he arrived in Aden?

Al-Essi: Do not worry about officials, their affairs are well-organized. We re-equipped state institutions, repaired what the war destroyed and helped supply the army with food and other logistical services. The government has not paid what it owes me to this day. Therefore, the last time we worked with it was in the end of 2016.

I did not benefit from the government, and I did not exploit my position or skills. They owe me to this day.

SC: How much does the Yemeni government owe you?

Al-Essi: The cost of food and so is around 500 million Saudi riyals (approximately US$133.3 million).

SC: These were salaries or just the cost of food? What were they exactly?

Al-Essi: Supplies to the army and the government, vehicles, repairs, camps, equipment and food. I performed the role of the National Economic Company.

SC: You basically performed the role of a governmental institution?

Al-Essi: At the beginning of the war, before the government appointed a director for the economic company to handle these matters. They haven’t paid me anything since the beginning of 2017. As for electricity, well of course as you know, I transported oil and fuel between Yemeni governorates for more than 25 years. I transported Safer crude oil from Ras Isa to Aden’s refineries and transported its derivatives from Aden’s refineries to Hudaydah, Mokha, Mukalla and Socotra.

At the beginning of the 90s, foreign companies left and I took over. After the Houthis seized Sana’a and after Operation Decisive Storm was launched, I stopped these activities – or perhaps before that, I think.

Refineries stopped pumping oil derivatives to northern governorates, and the Houthis stopped pumping crude oil to Aden’s refineries because the pipeline that supplies refineries in Ras Isa in Hudaydah is under their control. I kept 600,000 oil barrels until Aden was liberated, but my losses from keeping the oil in the Safer tanker in Ras Isa was US$1 million. The government owed me more than US$40 million during the war in Aden, and it hasn’t paid.

SC: Why?

Al-Essi: Because they were working on repairing roads to allow the port of Aden to resume work and meet the fuel needs of northern governorates, after the Saudi-led Arab Coalition suspended imports via Hudaydah port, and in order to prevent food or oil derivatives shortages in the north. Facilitations to import fuel to northern governorates without paying taxes and customs were granted. This is in addition to facilitations by security apparatuses to keep roads toward northern governorates open. However, they disagreed with the Emiratis and none of this happened. What happened was liberalizing the oil derivatives.

Of course, our fuel imports’ activities continued, then they announced tenders to import fuel to power plants. At the beginning several companies participated in importing fuel, but the government did not pay them and it did not even make commitments that it would pay. Meaning, the companies bought fuel and the government used to tell them we will pay later. Foreign companies did not deal with them because the country was in a state of war, and I was there so I began to import fuel.

The oil company was doing the work at the refineries to import fuel, and its bankruptcy was a result of not paying the fuel dues to generate electricity.

SC: But you even participate in formulating and designing tenders you also apply for?

Al-Essi: There are seven bodies that formulate the tenders: the oil company, Aden’s refineries, the ministry of finance, the Central Organization for Control and Auditing and the energy ministry, (etc.) Seven bodies do so, I don’t.

SC: It’s frequently said that no one can participate in a tender or engage in equal competition when Aden’s refineries are always loaded with Al-Essi’s supplies, and even the refineries themselves cannot do that; hence even when documents and the paperwork appear legal, practices differ.

Al-Essi: No, there is no relation between what you are proposing. If, for example, there is a tender to buy 40,000 tons of diesel or 50,000 tons of mazout, the ship arrives and unloads in the reservoirs in Aden without any objections, and Aden’s refineries pump them through the oil company.

As for electricity, no one can compete in this field as the power company is not paying money and it does not have money. It does not offer anything that would motivate you to work with it. It’s really exhausting. However, since it’s necessary to provide electricity, the government announces tenders even if it does not make payments.

Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek deceives people. Maeen’s friends were brought by merchants affiliated with the Houthis – [Zaid] Al-Sharfi, Al-Sunidar [group] and Al-Muqbali – who used to work in Hudaydah.

No one in Aden wants to bring in diesel. Why? Because if they buy a certain amount to make some profit, half of this amount or a quarter or 20 percent will be used to generate electricity.

SC: What do you think of Saudi ambassador Mohammed al-Jaber and his role?

Al-Essi: Mohammed al-Jaber works for the interest of his country, and he has found obedient Yemeni employees. He believes he has been successful. The problem is not him; it’s us, as Yemenis. Yemeni officials do not voice our desires and do not reflect our causes. Yemeni officials are serving their interests; they want to live, to receive a guaranteed salary, to keep their positions and to improve their relations with the Saudis, the Emiratis and even the Chinese. They do not want problems with anyone. They only want to please everyone.

SC: Let me ask something else: the presidential term of Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi entering its ninth year. It was supposed to be a two-year term only. Doesn’t the formula you just used to describe Yemeni politicians apply to him too? As in he too protects his circle or his post, even if he’s outside the country?

Al-Essi: What can he do? He does not enjoy the support of parties, there is no army that protects him and there is no economic power. He is in a difficult position, and there’s no doubt that there is also dereliction on his side. In the end, he’s in charge but he has his circumstances.

A Functional Animosity with the Emiratis

SC: Let me ask about Abu Dhabi. You are in a confrontation with the United Arab Emirates, or at least with its allies in Yemen and in Aden in particular, the STC and many forces in various areas. However, most of your money is in the UAE. How did you manage to combine all this?

Al-Essi: Are you hinting I work with the UAE?

SC: No, I am asking you how come your money in the UAE hasn’t been harmed if you say you are enemies?

SC: The UAE harmed me, and it wanted to eliminate me.

SC: But your money is in Dubai, this is what matters.

Al-Essi: I do not have money in Dubai. I only buy from Dubai in the name of my company, not in my name. I don’t go to the UAE, and if I did, I’d never be found again. My war with the UAE, the STC and the Houthis is no secret. Why do you doubt that?

SC: I do not doubt anything. I am asking you as a researcher. Explain this to me.

Al-Essi: Let me ask you, how do you see it?

SC: No, no. I am the one who is supposed to be asking questions here, and you have to answer me. Not the opposite.

Al-Essi: I’ll explain. I have to buy fuel from the UAE because it’s the best and the closest market and everything is available there. My office has been there since before the war erupted and before the UAE entered Yemen. The Emiratis have harassed our office and summoned its employees several times. However, our office has nothing to do with politics – the employees aren’t even Yemenis. The Emiratis tried everything. but we were clear and transparent, and then they began to say I import oil from Iran.

SC: But this is often said – that most of your oil comes from Iran.

Al-Essi: Let them prove this.

SC: So what is the source of your oil?

Al-Essi: All of it is from the UAE, and that is why my office is still there.

SC: And its main source is the UAE?

Al-Essi: I buy from the UAE. I don’t ask them where they bring it from. The UAE can investigate if there’s something that raises suspicions that I deal with Iran, although it is closer to Iran and the Houthis than us. If the UAE has the chance to convict me for dealing with Iran or the Houthis, it will not hesitate, just like it’s done with tens of Yemeni businessmen, including Al-Muqbali. The Emiratis raided their houses at night and detained them for more than a year and a half.

SC: They were oil traders accused of working with the Houthis?

Al-Essi: No, with Iran. Dealing with the Houthis is not prohibited.

SC: How?

Al-Essi: The Houthis secured oil supplies from the UAE through Bahraini, Iraqi, Iranian and Yemeni traders. Ten merchants are still detained in the UAE because they are accused of dealing with Iran. Two of them are Yemeni, [Sharif Ahmed] Ba’alawi and Al-Muqbali, and the rest are Iraqis and Bahrainis.

Their army (the Emiratis) that was in Aden, Mokha, Hadramawt and Socotra used to get its fuel supplies through me, they bought diesel fuel from me.

SC: They still do to this day?

Al-Essi: No, they no longer buy from me now.

SC: I heard that after the STC seized control of the city of Aden, the Emiratis had no way to access oil derivatives except through you.

Al-Essi: Yes, I told you, they want to kill me, yet they buy fuel from me. You’re telling me the STC is in control, but the STC has nothing to do with this. They did not find anyone else except me to provide their needs. And at the same time, it’s in my interest to open an office in Dubai. There is no problem with that.

Also, at the same time, I want them to show me evidence. All these accusations the UAE makes against me, well my office is there, why doesn’t it take necessary measures? Why are the Emiratis dealing with me in Aden? We are transparent.

I make point-blank accusations of corruption against anyone. I am clear, and I confront them in all arenas and squares. Am I stronger than all of them? I steal and loot and confront everyone? What do you think? Weigh this properly. Maeen joined them. Does this mean I am stronger than all these powers? Why couldn’t they prove any mistake I committed? ‘I eat the earths and heavens’, as you say about me at the Sana’a Center? Am I backed by foreign parties?

SC: I am asking you.

Al-Essi: I am directing this question to you.

SC: No, I am here to ask you questions, I don’t have answers.

Al-Essi: They say I am corrupt and I am this and I am that. Let’s assume it’s true. Aden has been under the control of the STC for two years and I work there. Why haven’t they arrested me and tried me at a court or even a militia tribunal?

I’d say the same about the UAE. My office is there in the UAE. The UAE had authority in Yemen and I was present in Aden and they wanted to assassinate me twice. They sent gunmen to assassinate me.

Why haven’t they arrested me? Why haven’t they done anything? The thing is all people think they (those in Aden) are liars and weak. If I am to think of my business interest, the Houthis will salute me and will deal with me, although they are our enemies. They do business like real men, better than the legitimacy and the Coalition. Do you know that when someone works with the Houthis, the latter keep their word and pay them? If you do not oppose the Houthis in politics, you live like a prince.

The UAE, the Houthis or Maeen – Who is the Enemy?

SC: I have a question. If I ask you to rank them, who are your enemies? The UAE, the Houthis, Maeen or the STC?

Al-Essi: Honestly, I do not think Maeen deserves to be described as an enemy but…

SC: The rest?

Al-Essi: The Emiratis insist on killing me.

SC: More dangerous than the Houthis?

Al-Essi: No, the Houthis are certainly more dangerous, but there’s nothing personal toward me. The Houthis’ problem is with the entire country, and I am part of the national component. The UAE is targeting me personally while the Houthis are in a defined position. We all acknowledge that the Houthis are an enemy who stole our property and prevented us from entering our country. There is no need to talk about this.

Regarding my relation with the UAE, the Houthis and Maeen Abdelmalek. When talking about the Houthis, I noted that they work for certain interests and business purposes. As for Maeen, he represents the government and he’s not supposed to be handling matters by making accusations through media outlets.

Maeen sacked Interior Minister Ahmed al-Maysari and Transport Minister Saleh al-Jabwani. He passed whatever decisions he wanted. Is it difficult for him to prove my corruption? Why doesn’t he prove it? My dispute with him is business-related, I view him as a competitor in business.

He supports business interests he is associated with and he ignores the general interest. He focuses on issues that are not important. Who is authorized to discuss the implementation of the Riyadh Agreement? Isn’t it him? Has he spoken about the security and military aspects of the Riyadh Agreement? Has he tried to solve problems in Aden’s port and airport? People and businessmen face so many difficulties in Aden’s port, has he achieved security? He should go ahead and do so. What was his stance regarding the Central Bank issue? He prevented the issue from reaching the judiciary. The Central Organization for Control and Auditing exposed violations at Tadhamon Bank, which is affiliated with the Hayel Saeed Anam & Co, and at Al-Kuraimi Bank. Why haven’t these cases been addressed? The Central Organization for Control and Auditing exposed them and raised the matter to the judiciary, but Maeen obstructed this. There’s corruption when handling the Saudi deposit, and corruption activities such as looting people’s land.

Who Should be the Next Yemeni President?

SC: One last question. Let’s assume there is a transitional process after a year or something, god forbids, happens to Hadi. Who is your candidate for the presidency, and don’t sell me the talk ‘names are not important’. Tell me a name, who is your candidate for the presidency?

Al-Essi: Well, in that case, and if something happens to Hadi, I think I am the best among all those in the arena. Frankly, my proposed name is Ahmed al-Essi. I see myself as a combination of the authority of Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar, Shaher Abdulhak and Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Commentaries

The Panel of Experts Err on Yemen

By Rafat Al-Akhali

On January 22, 2021, the Panel of Experts (PoE) on Yemen issued its annual report to the United Nations Security Council. This year’s report summarizes the PoE’s views on the peace process as well as on the security, stability and economic situation in the country during 2020. The report leveled accusations of corruption, money laundering and elite capture against the internationally recognized government of Yemen, the Aden-based Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) and Yemeni food importers, relating to a US$2 billion deposit made by Saudi Arabia in 2018 to help finance the import of commodities and stabilize the Yemeni rial. Although the panel’s mandate is to report on acts that threaten the peace, security and stability of Yemen, the section on the use of the Saudi deposit included a number of significant factual and methodological errors which, if left unaddressed, could themselves have dire consequences for the humanitarian crisis in Yemen.

My reflections here are limited to Part B of the report’s Section IX, “Economic context and overview of finance”,[1] and the associated Annex 28, “Case Study on the Saudi Deposit: embezzlement of 423 Million USD.”[2] These reflections do not in any way apply to other sections of the report.

The PoE report makes three main claims with regard to the use of the Saudi deposit. First, CBY-Aden and the government violated the former’s mandate and Yemeni laws by selling foreign currency to food importers below the market rate. Second, these preferred rates were not reflected in food prices and market exchange rates, hence the report determines these transactions to have constituted corruption and money laundering. Third, practically all food-importing companies in Yemen (91 in total) – particularly the largest importer, the Hayel Saeed Anam (HSA) Group – are party to a money-laundering and diversion-of-funds operation, representing a form of elite capture.

In the following sections, I will highlight the factual and methodological flaws in the report, as well as the potential repercussions on food security and the humanitarian situation in Yemen.

Illegality of the Preferential Exchange Rate

The PoE report claims that the government-implemented policy of giving food importers a preferential exchange rate is illegal, as it violates “a number of Articles in the Central Bank Law No. 14 of 2000 and the provisions of Law No. 21 of 1991 regarding the CBY.”[3] It further argues that “central banks throughout the world are, in theory, profit-making institutions for their governments. However, the CBY in Aden is clearly not acting in the best interests of the [government] in this case.”

It is a well-known fact – and a public one – that CBY provided food importers with a preferential exchange rate for imports supported by the Saudi deposit as part of its stated monetary policy to manage the exchange rate.

It is not clear why the PoE references both Law 21 (1991) and Law 14 (2000), given that the latter superseded the former. Perhaps the PoE was only able to find an article remotely relevant to its claim in the outdated 1991 law. That article stipulates that CBY should aim to secure “the largest possible return from dealing with highly rated banks in order to obtain the highest possible return while observing the safety factor. And dealing with the Bank for International Settlements, the Arab Monetary Fund, and the World Bank to manage part of these reserves (sic).”[4] This article, however, is irrelevant to the PoE’s claim as it relates to deposits made by CBY internationally, and not to the issue supposedly being analyzed by the PoE, which is the management of foreign exchange monetary policy in the country.

In the current, applicable law, which is unequivocally clear in defining the mandate of the CBY, there is no such article. Law 14 (2000) states that “the main objective of the bank is to achieve price stability and preserve that stability and provide adequate liquidity to create a stable financial system based on market mechanisms.” Articles 2, 23 and 47 of the law clearly require the CBY to design a foreign exchange regime in consultation with the government to achieve price stability.

The PoE’s claim that the mandate of central banks worldwide is to make a profit for their governments is debatable, but to claim that this should be the mandate of a central bank in a conflict-affected country like Yemen raises serious questions about the PoE’s technical expertise and knowledge of the subject at hand.

What is certain is that the CBY and the government did not violate any mandate or laws in adopting a preferential exchange rate policy. Whether or not this was the best policy approach to achieve price stability and address food insecurity in the Yemeni context is debatable, but a PoE report is not the platform for such a debate.

Corruption and Money Laundering

The PoE claims that the preferential exchange rate offered to food importers through the Saudi deposit was not reflected in the value of the Yemeni rial or in food prices. As a result, the PoE concluded that the administration of the Saudi deposit was corrupt and amounted to money laundering. This accusation is leveled not only at the CBY and the government, but also at food importers in Yemen, virtually all of whom have benefitted from the Saudi deposit.

To support its claim, the PoE states that “in 2019, the Yemeni rial depreciated by 23 percent versus the United States dollar and as a result, the price for the minimum food basket increased by 21 percent.”[5] As evidence, the report cites an August 2020 World Food Programme (WFP) report. However, the WFP report refers to a year-on-year change in prices from August 2019 to August 2020, not for the year 2019, as the PoE claims. The PoE also references a November 2020 WFP assessment, which reported that “the cost of the minimum food basket had increased remarkably during the first half of 2020.”

These dates are critical because the Saudi deposit was primarily used between October 2018 and January 2020, as documented by the PoE report itself.[6] Thus, any assessment of the impact of the deposit should focus on this period and not, as the PoE does, on a later period.

Indeed, an examination of WFP and World Bank reports focused on exchange rates and food prices from this earlier period leads one to a conclusion at odds with that reached by the PoE. In December 2018, the WFP reported that “the Yemeni rial started to regain its value since mid-November slowly. The steady recovery of the Yemeni rial and its continued gains against foreign currencies including the US dollar resulted in a significant decline in the prices of food and fuel commodities.” This report goes on to state that “during the month of reporting, the national average exchange rate stood at YR517/US$1, appreciated by 15 percent from the previous month.” The exchange rate began moving up again at the end of 2019, mainly when the use of the deposit slowed down and eventually stopped, showing the use of the Saudi deposit had a clear positive impact on the exchange rate.

A World Bank report from December 2019 also points out that “continued import financing support by the CBY Aden has played a vital role in stabilizing the prices of essential food during 2019.” This report notes, correctly, that “a range of other factors – parallel market exchange rate, political and security instability, uncertainties in trading and import arrangements, dual taxation, and fuel availability – also affect food prices.” This is a crucial point, which the PoE completely ignores.

Elite Capture

The PoE report states that 91 food-importing companies in Yemen “received a US$423 million windfall by simply applying for the letter of credit mechanism representing a bonanza for their business and personal wealth. In the panel’s view, this represents a clear case of money laundering and diversion of funds perpetrated by a government institution, in this case the CBY, to the benefit of a select group of privileged traders and businessmen.”[7]

The PoE singles out the HSA Group as the recipient of 48 percent of the deposit, labeling this share a form of “elite capture”. The report fails to mention, however, that HSA Group, the leading business and industrial conglomerate in Yemen since the 1960s, has been the largest food importer in Yemen for years.

A 2018 World Bank report noted that HSA Group accounted for 50 percent of wheat imports to Yemen between 2014 and 2016. For the PoE to take one statistic (the proportion of the Saudi deposit allotted to the HSA Group) without situating it in context is a questionable investigative practice.

The PoE asserts that “between mid-2018 and August 2020, the Hayel Saeed Anam Group made a profit of approximately $194.2 million from the letter of credit mechanism alone, excluding profits made from the import and sale of commodities.”[8] It appears that the PoE reached this conclusion by doing a back-of-the-envelope calculation based on the spread between the PoE’s reported market exchange rate – no exact source is provided for that rate – and the CBY exchange rate offered through the Saudi deposit.

According to the PoE report’s Annex 3, which includes a summary of the panel’s correspondence, the PoE did not even bother to contact the HSA Group in order to request details on its pricing or to give it the opportunity to reply before the report was published.

I believe this PoE report to be a serious violation of the “do no harm” principle. The report makes serious and unsubstantiated accusations against all of Yemen’s food importers, based on faulty logic and poor practice. The panel’s conclusions are a significant overreach of its mandate.

Yemen’s food importers are the country’s lifeline. The panel’s overreach is a threat to food security in a country the UN itself describes as “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.” Already, food importers in the country report facing additional difficulties with food suppliers and international banking transactions due to the PoE report. The PoE exists to report on the state of the war and monitor the sanctions regime. But this year, the panel has negatively contributed to the war’s impact on Yemeni citizens.

Rafat Al-Akhali is a fellow of practice at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. Al-Akhali served as Yemen’s Minister of Youth and Sports from 2014-2015.

Endnotes

- 1. “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen,” UN Security Council, January 25, 2021, pp. 36-38, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_2021_79.pdf; 2. Ibid. pp. 222-240; 3. Ibid. pp. 229; 4. Ibid.; 5. Ibid. pp. 37; 6. Ibid. pp. 223-224; 7. Ibid. pp. 225; 8. Ibid. pp. 38.

Marib and the Closing Bell of the Yemen War

By Abdulghani Al-Eryani

As fighting intensified in Marib during the month of February, along with signs of escalation on other fronts across the country, I am hopeful. The risk of an outright victory by the armed Houthi movement over everyone else, and over the chance of peace among equals that could keep Yemen in one piece, has finally triggered a series of events that could make peace possible. Let me explain this counterintuitive notion.

For several years, I have been speaking about five obstacles to peace in Yemen.

The first is the war economy. The collapse of the Yemeni state, and the extraordinary conditions of war, have made it possible for people in the right places to profit in ways they could never manage in peacetime.

On the Houthi side, the need to ‘defend Yemen against international aggression’ has been used to muffle voices of protest against naked looting that turned semi-literate Houthi apparatchiks, known as supervisors (mushrifeen), into billionaires overnight. Salaries are not paid and services are not delivered, freeing up hundreds of billions of Yemeni rials for corruption. Properties of Yemenis who opposed the Houthis were confiscated or outright looted by members of the movement. Harsh, often arbitrary, tax collection raised revenues by 500 percent, according to a credible source in Sana’a. The collection of illegal fees – from businesses, property owners, farmers and even school children – has reached absurd levels. Surcharges on petroleum products, imported mostly by companies owned by members of the movement, were at one point equal to the entire tax revenue that Houthi authorities collected, according to the same source. Humanitarian assistance by the World Food Programme (WFP) is routinely and widely diverted. Real estate in Sana’a, in the middle of war and a crushing economic crisis that leaves many teetering on the edge of famine, has witnessed a boom not seen in a long time.

Corruption and war profiteering is equally rampant on the side of the internationally recognized government. The government’s main source of funds is Saudi Arabia. According to a cabinet-level Yemeni government official who spoke with the Sana’a Center, the Saudi government was meant to transferred the sum of 40 billion Saudi riyals (US$10.66 billion) to the internationally recognized government in 2015-2016, though it received only SR25 billion (US$6.66 bn). The official said the Yemeni government representatives receiving the payment had to give the Saudi officials delivering it SR10 billion, a common practice in the Kingdom. Two-thirds of the remaining SR15 billion went directly to the pockets of the top Yemeni leadership, and the remaining SR5 billion – one-eighth of the originally intended transfer – was used to meet government operational expenses and pay salaries. With this massive sum going only to a small circle at the top, other officials below them were forced to line their pockets with money from other sources. Revenues from crude oil and cooking gas sales are often not deposited in the Central Bank of Yemen. Humanitarian aid provided by the Saudi King Salman Center is also subject to massive diversion – for instance, political party leaders in Taiz told me that the Center makes monthly allocations of thousands of food baskets to distribute to loyalists at their discretion, with many of these sold on to commercial traders. Often, ill-gotten profits from the conflict have gone to purchasing real estate in Cairo, Istanbul and a host of other destinations.

On the Saudi side, a European ambassador to Yemen said his government estimated the cost of Saudi operations in Yemen at US$5-6 billion annually. A different diplomatic source with access to the Saudi Royal Court spegged the cost of Riyadh’s Yemen operations at SR200 million per day (close to US$20 billion annually). The margin of corruption is simply astounding.

Following the failed Kuwait peace talks in 2016, there was a preponderance of evidence that the war economy was the salient factor in the conduct of the war. Violence was reduced to an endurable level; fronts remained static and commercial arrangements were reached to allow the economy to lumber along and for the warring parties to share the profits. Maintaining the status quo was clearly the objective of Saudi command when it prevented government forces from advancing toward Sana’a throughout 2016-2018, as reported publicly and privately by dozens of top Yemeni generals and political leaders, such as Presidential Advisor Abdul Aziz Jubari. Commanders who dared to advance against Saudi wishes were stopped by the bombs of the Royal Saudi Air Force, top commanders told me privately. Some of them were relieved of their duties. For example, in 2017, General Mohamed Abdallah Al-Ethari led a unit that reached the Nehm-Arhab Junction. His unit was bombed by the coalition and he and his lieutenants were recalled to Marib, relieved of their command, and reassigned to desk jobs.

The United States and the United Kingdom were complicit in that travesty. Both continued supporting Saudi Arabia despite knowledge of its untenable situation. No one was willing to tell the emperor he had no clothes. In effect, they were selling Saudi Arabia the rope by which it will hang itself. At the White House, relations with Riyadh were managed directly by President Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, reducing the effectiveness of institutional corrective mechanisms and allowing short-term, and possibly personal, interests to trump American strategic interests. As for the UK, the limited leverage it had on Saudi Arabia and the Yamamah arms deal, –the largest export agreement in British history – kept Downing Street quiet.

The UN mission to Yemen, most notably the office of the special envoy, has been equally culpable in failing to recognize the centrality of the war economy to the Yemen conflict. Rather, it has continued to chase the mirage of a peace that will somehow materialize out of thin air.