Food Security Deteriorates Amid Aid Cuts, Sanctions, Conflict, Inflation

Yemen is hurtling toward a humanitarian crisis due to a confluence of factors: sharp aid cuts, escalating conflict, crippling sanctions, and a collapsing currency.

On April 7, the Trump administration ended almost all US aid to Yemen as part of sweeping cuts for more than a dozen countries. The cuts came at a critical time, as Yemen was already grappling with severe shortfalls to its annual Humanitarian Response Plan. The withdrawal of US funding, which accounted for half of last year’s budget, has had a profound impact. The World Food Programme (WFP), which relied on the US as its largest donor, said the end of American food aid “could amount to a death sentence for millions of people facing extreme hunger and starvation.” In Yemen, the cuts totaled US$107 million. Life-saving food assistance to 2.4 million people and nutritional care for 100,000 children would be completely halted as a result, according to a WFP assessment.

The humanitarian outlook remains grim. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) estimates that the number of Yemenis facing high levels of acute food insecurity will reach 18.1 million, 52 percent of the population, by February 2026. According to WFP projections, 4.8 million Yemenis were at risk of losing food aid due to overall cuts in humanitarian funding. Forty civil society organizations operating in Aden reportedly issued an urgent humanitarian appeal to the UN Security Council on June 4, calling for immediate intervention. The call was echoed by over a hundred aid organizations, as only US$265.2 million (10.7 percent) out of the US$2.48 billion required has been raised for the 2025 humanitarian response plan.

Compounding the crisis are airstrikes on civilian and dual-use infrastructure. US and Israeli strikes in April and early May curtailed the ability of Yemen’s Red Sea ports to handle humanitarian and commercial cargo. According to a statement from the Houthi-aligned Yemen Red Sea Ports Corporation, the direct cost of damage to the ports of Hudaydah, Al-Salif, and Ras Issa was over US$531 million, with the indirect cost from the suspension of services estimated at around US$856 million. The attacks targeted the operational infrastructure of the ports, destroying docks, cranes, power plants, generators, and logistics facilities, including warehouses used for unloading food, aid, and medicine. The Red Sea ports are crucial to the economy and the delivery of humanitarian aid, serving as the primary delivery point for the majority of imported food and medicine designated for Houthi-controlled areas. Although the rest of the Red Sea ports remained operational, the port of Hudaydah has seen shipping suspended due to the extensive damage it sustained from Israeli airstrikes in mid-May.

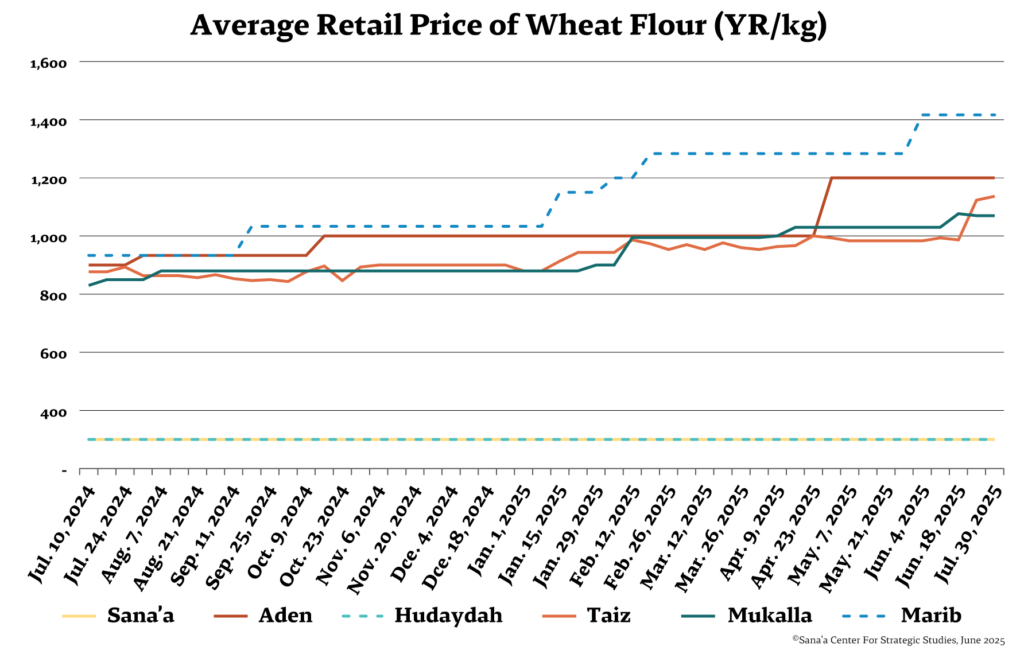

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) projected that conflict, aid cuts, and currency devaluation will leave an estimated 17.1 million Yemenis facing high levels of acute food insecurity this year. The plummeting of the new Yemeni rial (YR) in government-controlled areas has impacted food and fuel prices, which have surged dramatically. In May, the cost of a Minimum Food Basket (MFB) in government areas was 37 percent higher year-on-year and 49 percent above the three-year average. In Houthi-held areas, although the exchange rate, fuel, and food prices remain relatively stable, degraded port infrastructure poses a significant risk of further fuel price hikes or shortages, and could have ripple effects on food prices due to increased transportation costs. The relative price stability of the MFB in Houthi-held areas is no reason for optimism – much of the population is experiencing reduced purchasing power due to a lack of humanitarian assistance and fewer sources of income.

Yemeni households living in areas under Houthi control have been unable to receive remittances sent in foreign currencies, particularly US dollars. Due to the liquidity crisis and limited US dollar reserves, money exchange shops have reportedly refused to process remittances sent in dollars, with very few exceptions. Beneficiaries may receive remittances in Yemeni rials, or Saudi riyals with a conversion fee of up to YR1,000 for every US$100. The US redesignation of the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) has exacerbated financial constraints for the Yemeni banking sector, posing significant difficulties to UN agencies processing cash payments to their partners, which further complicates aid delivery. It has also prompted the Houthis to tighten their control over the banking system and economy in order to secure funding for their activities.

Sanctions Target Houthi Revenues

The US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has continued to hit Houthi revenue sources as part of a broader US strategy to disrupt the Houthis’ financial networks and banking access and help in “eliminating Iran’s threat network.”

The US ban on refined petroleum imports and exports through Houthi-controlled ports in Hudaydah, effective from April 4, is likely to deprive the group of a significant revenue stream. According to the Yemen-based Stolen Assets Recovery Initiative, the Houthis collected US$789 million in tax and customs revenues from oil derivatives and other commodities through the ports of Hudaydah, Al-Salif, and Ras Issa between May 2023 and June 2024. However, the UN Panel of Experts and government authorities have long pointed to smuggling as one of the Houthis’ main streams of income, and black market activities are expected to expand in areas under Houthi control as the ban takes effect.

On June 20, OFAC announced its “single largest action to date” against the Houthis, sanctioning 12 entities, four individuals, and two vessels. The sanctions targeted a network of Houthi-linked oil trading and shipping entities, including front companies in Sana’a and Hudaydah, accused of smuggling and selling Iranian oil to fund the group’s military operations. Among the most notable were Black Diamond, sanctioned for smuggling Iranian oil and generating substantial income for the Houthis; Star Plus, for brokering oil deals and smuggling dual-use weapons components from Asia; Tamco, for obscuring oil supply chains and beneficiary identities; Royal Plus, for handling oil transactions tied to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and managing crossborder payments for weapons from Iran and Russia; Al-Usaili Co. and Gasoline Aman, for facilitating oil imports and obscuring Houthi involvement in financial transactions; Azzahra, for large scale money laundering from oil sales; Yemen Elaph (owned by Houthi operative Abdullah Dabbash), for selling oil via the black market and holding exclusive port rights; and Abbot (run by Houthi businessmen Ali Ahmed Daghsan Talea and Daghsan Ahmed Daghsan), for facilitating the illegal oil trade and funneling revenue to Houthi authorities.

The sanctions also targeted vessels, as well as their owners and operators, that violated US sanctions by discharging oil derivatives at the port of Ras Issa after the April 4 deadline. The Valente, linked to Best Way Tanker Corp., unloaded more than 60,000 metric tons of gasoline at Ras Issa, and the Atlantis MZ, linked to Atlantis M Shipping Co., had unloaded nearly as much by mid-June. The Sarah, formerly Tulip BZ, was sanctioned for facilitating the delivery of liquid petroleum gas (LPG) to Ras Issa.

Following the Houthis’ FTO designation, OFAC sanctioned various individuals and entities found to have materially supported the group, including the International Bank of Yemen (IBY) on April 17, citing its continued financial support of the Houthis. OFAC simultaneously sanctioned the IBY’s top management for their roles in channeling support: Chairman Kamal Hussein al-Jabri, Executive General Manager Ahmed Thabet al-Absi, and Deputy General Manager Abdelqader Ali Bazara’a. The IBY is the second Yemeni bank to be directly sanctioned by OFAC after the Yemen Kuwait Bank for Trade and Investment in January. OFAC’s press release alleged that the IBY and several key officials granted Houthi authorities and companies linked to the group access to the SWIFT network, allowing them to purchase oil, evade sanctions, and mobilize resources. The sanctions completely severed the IBY’s connections to the international financial system, including the SWIFT network. US-owned financial transfer providers such as Western Union and MoneyGram have terminated their relationships with the bank, disrupting millions of dollars in remittances and other transfers.

IBY played a vital role in facilitating humanitarian aid delivery, managing funds for UN agencies, INGOs, NGOs, and civil society organizations during the conflict. The sanctions have disrupted this critical function, forcing humanitarian organizations and Yemeni businesses to seek alternatives. The IBY is Yemen’s largest commercial bank in terms of customer deposits, holding YR466 billion (approximately US$880 million), and its financial assets constitute roughly 15 percent of the sector’s total assets. The bank has historically maintained a dangerously undiversified investment portfolio, holding close to one-third of the total public debt in treasury bills, with investments amounting to approximately YR700 billion (US$1.3 billion). Since late 2016, commercial banks have been essentially barred from liquidating government debt and denied regular interest rate payments. The Houthis’ attempt to “Islamize” Yemen’s financial system through its 2023 anti-usury law, which banned interest-based transactions entirely, exacerbated the issue, as 80 percent of IBY’s financial assets were trapped in government treasury bills. In May 2024, dozens of depositors protested in front of the IBY headquarters in Sana’a, demanding access to their frozen savings and the resumption of interest payments. The IBY had been one of the few banks still offering such relief, disbursing gradually decreasing amounts before stopping entirely in March 2024. Since then, it has teetered on the edge of a financial abyss. Now, rumors of its impending bankruptcy have sent shockwaves through Yemen’s fragile financial sector, stirring fears of a wider collapse. The IBY’s troubles are a stark reflection of broader financial instability, and US sanctions could create a dangerous domino effect as Yemen’s financial sector is still largely concentrated in Sana’a.

On March 15, the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) published the names of eight banks planning to relocate their headquarters to Aden in an effort to avoid potential US sanctions. As Houthi authorities tightly control banks in Sana’a, relocation comes with logistical and political challenges. OFAC stated it was committed to assisting government efforts to protect the Yemeni banking sector from Houthi interference.

Energy Crisis in Aden

Prolonged power outages and fuel shortages continue to hit government-held areas of Yemen, with major blackouts reported in Aden, Shabwa, and Socotra. Aden’s Al-Raies (PetroMasila) Station was forced to shut down on April 27 due to a lack of fuel. After widespread blackouts affecting an estimated 70 percent of the city, the station resumed limited production at 60 megawatts the day after. The Aden General Electricity Corporation warned that the station could only continue to operate if crude oil continues to be shipped from Hadramawt and Marib, where local forces have, at various points, prevented its transport. In response to the blackouts, protesters in Aden blocked several main roads on April 28, demanding a radical overhaul of the deteriorating electricity sector. The Aden General Electricity Corporation has repeatedly called on the government to develop permanent solutions to address the lack of fuel and regular power outages. Dilapidated infrastructure in Aden and several other governorates is another major factor in regular electricity cuts. Oil-rich Shabwa governorate experienced power outages in mid-April lasting more than a week, reportedly due to a lack of fuel and technical failures at power stations resulting from inadequate maintenance. In Socotra, the island archipelago controlled by the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC), the Emirati Eastern Triangle Company dramatically increased fuel prices for the fifth time this year. According to local activists, Emirati companies have monopolized the market in Socotra, excluding local suppliers and taking control of ports and distribution outlets.

Upon assuming office, Prime Minister Salem bin Breik directed the rapid supply of emergency fuel to power plants in Aden, stating he was taking “all necessary measures to reduce the hours of power outages and work within available capabilities to alleviate the suffering of citizens.” However, the arrival of two additional shipments of fuel (13,000 tons of diesel and 13,000 tons of mazut) only temporarily alleviated the situation.

In late May, Aden and the neighboring governorates of Lahj and Abyan experienced severe gas shortages ahead of the Eid al-Adha holiday, a period of heightened demand for cooking gas and major activity in the service and transportation sectors. Local media attributed the crisis to a deliberate and calculated manipulation of gas supplies, which caused long queues at filling stations. Residents described a sudden disappearance of domestic gas from sales points, with remaining quantities going for double the normal price. Filling stations pointed to reduced domestic gas supplies, but this was denied by the government-affiliated Yemen Gas Company, which stated on June 7 that there had been no interruption to supply, and that Aden’s allocation of domestic gas had been increased by 60 percent. According to the company’s statement, 368 tankers transported gas from the Safer facility in May and 98 in the first week of June.

The government has struggled to tackle the ongoing energy and electricity crises as the economic situation worsens. On June 28, local media reported a further increase in fuel prices in Aden, marking the sixth price hike in June. A source at the Yemen Oil Company (YOC) explained that the price increase was due to the ongoing decline in the exchange rate of the local currency.

The energy sector also faces challenges related to inadequate infrastructure, insufficient government oversight, corruption, and extortion. Truck drivers transporting domestic gas to Aden recently told local media that they had been stopped at a security checkpoint in Abyan, where security forces demanded a YR200,000 toll as an “improvement” fee, which had not been required before. Stalled transportation has been affecting the stability of domestic gas prices in local markets. Tribal leaders have been stopping trailers as bargaining tools and charging unusual fees without any action from the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), leading to frustration among citizens. On June 24, the Hadramawt Inclusive Conference accused the PLC of worsening service delivery and living conditions, and suggested the possibility of pursuing self-rule for the oil-rich governorate. This is likely to further strain the already contested governance of the PLC, weakening social and political unity.

Rial in Free Fall

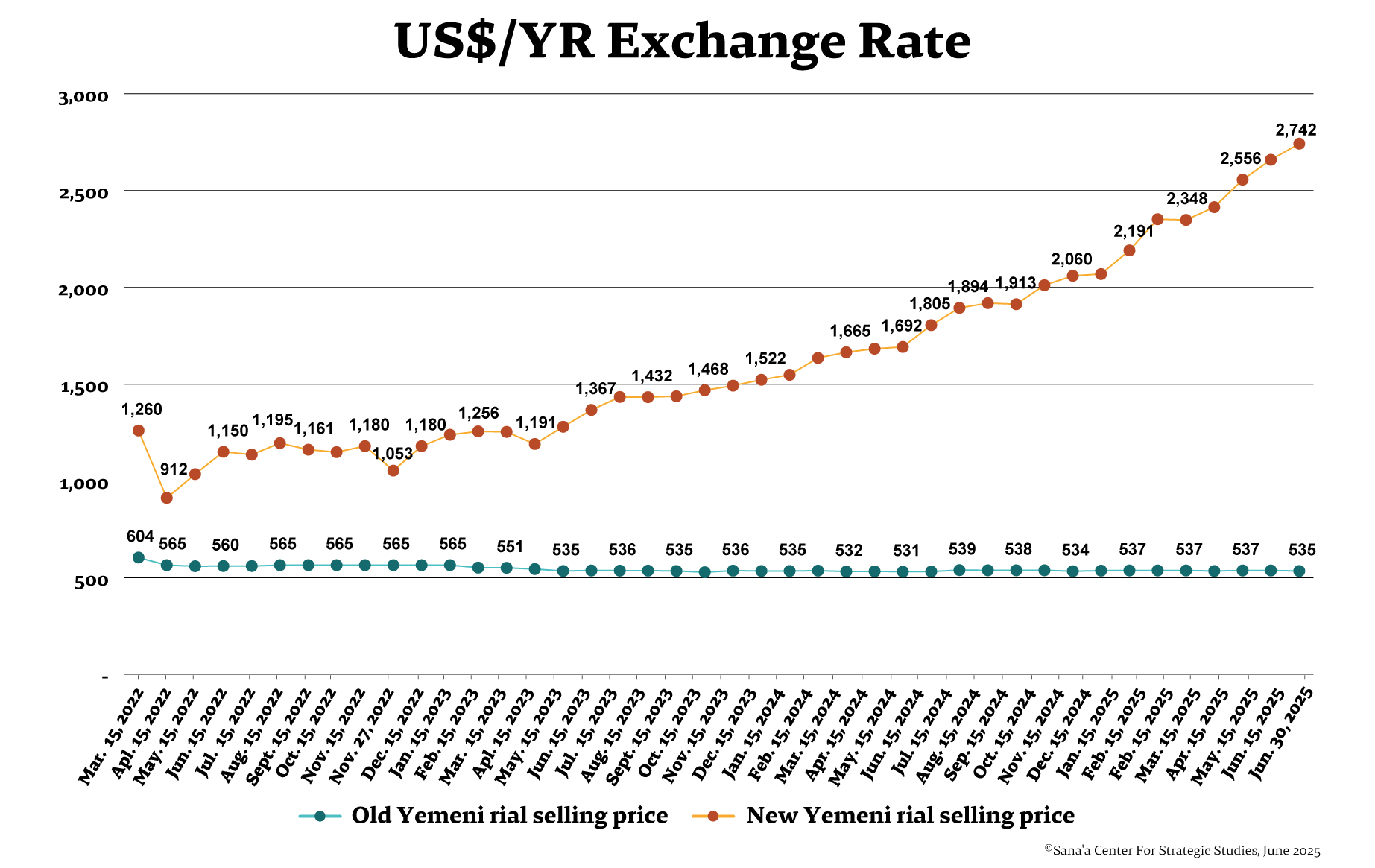

The new rial continued to depreciate in government-controlled areas, hitting a record low of YR2,742 per US$1 by the end of the reporting period. This represents a 34 percent decline since the beginning of this year, and a 78 percent drop since the start of 2024. Old rials trading in Houthi-controlled areas remained stable, trading at YR535 per US$1.

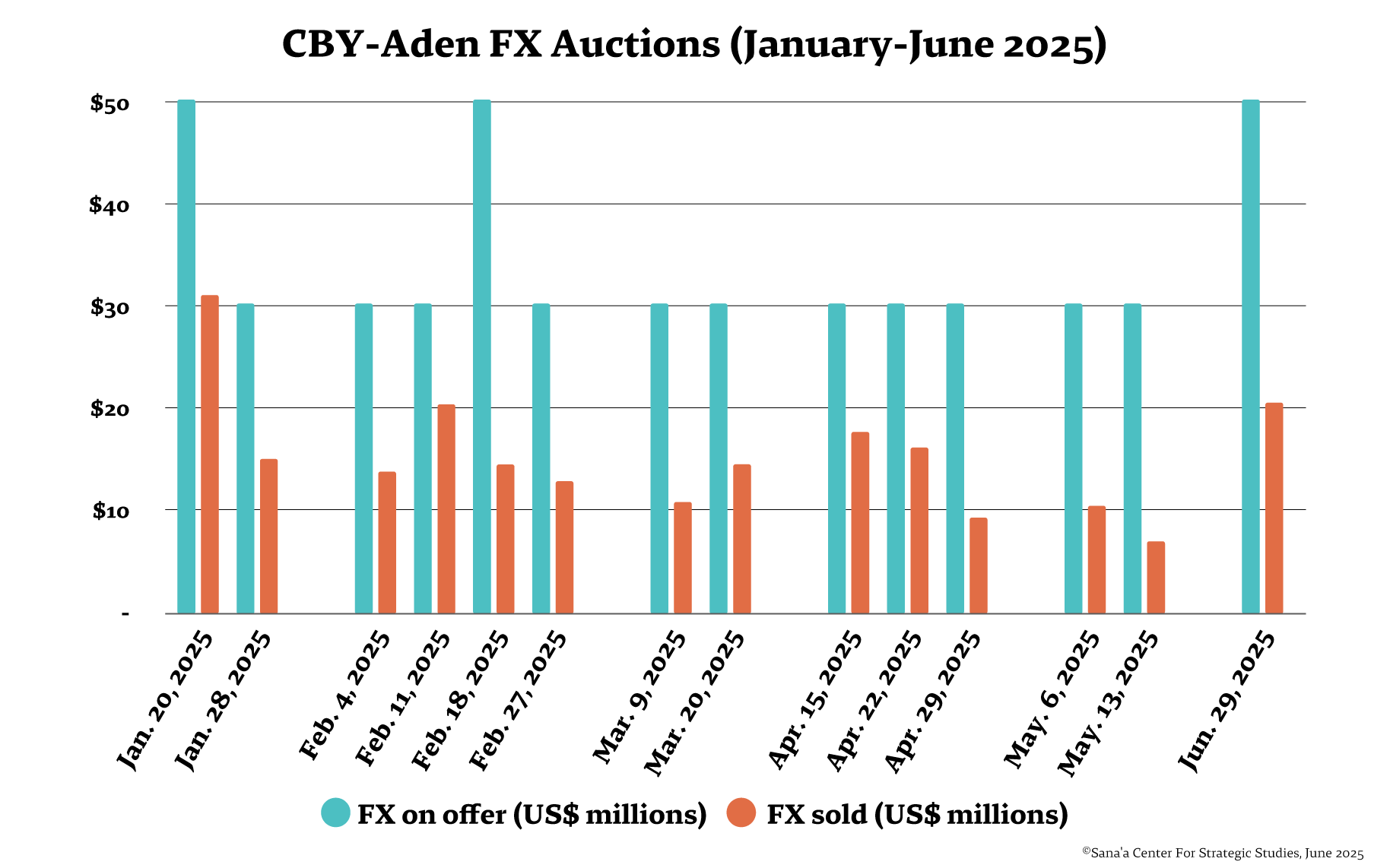

Several factors contributed to the rial’s decline, including dwindling foreign currency reserves, insufficient and irregular Saudi financial support, the government’s fiscal crisis and lack of revenues, and the central bank’s weakened authority. Houthi military action in the Red Sea and against Israel, and US, British, and Israeli airstrikes in Yemen have exacerbated the situation, leading to increased demand for foreign currency and disrupting supply chains. One of the central bank’s primary tools to address depreciation has been the use of foreign currency auctions. However, the 14 auctions held this year have witnessed declining interest, with the most recent one, held at the end of June, following temporary postponements in mid-May. It saw the worst subscription rate of the year, with just 22 percent of the US$30 million on offer purchased by participating banks. Even when the central bank could afford to hold them, the FX auctions did little to stem the rial’s decline.

Money exchangers have been the primary drivers of the freefall, engaging in rampant currency speculation and manipulation by artificially inflating demand for hard currency within government-controlled areas, deliberately devaluing local currency. In response, the CBY-Aden issued a directive demanding that all exchange companies and money exchange shops cease foreign currency transactions until further notice, threatening violators with severe punitive measures. This directive has yet to be fully implemented. The government’s persistent fiscal crisis and unreliable Saudi financial support have left the CBY-Aden with dangerously depleted foreign currency reserves, limiting its capacity to contain the rial’s volatility. Rumors that the bank may resort to printing new currency have persisted, amid a lack of clear options to tackle the crisis. Printing more banknotes at this stage would likely promote further inflation and price increases, and contribute to public unrest within government-controlled areas. On May 21, the CBY-Aden strongly denied these claims, stating that the bank had completely ruled out printing new currency to address the financial crisis.

Government Seeks International Support

The World Bank’s Spring Yemen Economic Monitor report highlighted how ongoing conflict, institutional fragmentation, and declining external support are compounding long-running crises in Yemen and severely straining the economy. Nominal GDP per capita is projected to drop by 19 percent while real GDP is expected to contract by 1.5 percent in 2025.

Facing increased pressure from citizens to resolve ongoing economic crises, the government and its central bank have been seeking international assistance. Central bank representatives appealed to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) asking for emergency funding in April and Yemen’s ambassador to the United Nations, Abdullah al-Saadi, called on the Security Council for assistance in resuming oil and gas exports to alleviate the economic crisis and reduce dependence on international aid, stating the government had lost more than US$7.5 billion in expected oil and gas revenue since 2022. Though negotiations continue, the government has failed to secure emergency funding from the IMF, with media outlets reporting that donor agencies “are expressing reservations about the way the government is handling the economic situation.” The CBY-Aden has attempted to stabilize the currency and combat speculative trading, but has so far been unsuccessful. Repeated government promises of significant reforms have also gone largely unfulfilled. Most recently, local media reported that the government had plans to raise the customs exchange rate from 750 rials to the US$1, closer to the market rate, which now exceeds 2,700 rials to the US$1.The increase will not include basic food items such as wheat, rice, sugar, baby formula, medicine, or cooking oil. The government also recently lowered freight transport fees to Houthi-held areas by 20 percent to offset diminishing purchasing power. Despite these efforts, continued currency depreciation and limited funds leave the government in an impossible situation: it needs access to funding to stabilize the political and economic situation, but the provision of that funding seems to be conditional on greater stability.

Starlink Launches in Yemen Amid Houthi Threats

On May 12, the Public Telecommunications Corporation in Aden verified that it had received its first shipment of Starlink satellite internet devices. The launch followed the government’s September 2024 announcement that SpaceX’s Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite services would become available in areas under its control. Yemen is the first Middle Eastern country to offer Starlink services. Houthi authorities have opposed its deployment, citing national security and foreign meddling, and have threatened to confiscate equipment. Yemen suffers from outdated Internet infrastructure, and access is slow, expensive, and often unavailable, especially in government-controlled areas. Starlink offers the potential of a dramatic leap forward in connectivity. While there have been promises that prices will be kept low, the current economic crisis will still put the service out of the reach of many Yemenis.

Turnover in Oil Sector

On May 8, the Yemen Oil and Mineral Investment Company (YECOM) published a decision to hand over Block 5 of the Usaylan District in Shabwa governorate to a new operator, Jannah Hunt, which is set to replace the previous operator, PetroMasila. According to the decision, the Jannah Hunt Oil Company, which also owns part of the oil field, will implement the 2025 operating budget it proposed. The decision follows months of tension between the operating partners, with PetroMasila accused of breaching the operating agreement, committing violations, and purchasing other partners’ shares.

On May 25, Prime Minister Bin Breik issued an urgent directive to the Ministry of Oil to institute a new government committee for the management of the Aqla (S2) oil sector in Shabwa governorate. This comes in the wake of the Austrian energy company OMV’s decision to cease its operations in Yemen at the end of May.

Yemenia Airways Caught in the Crossfire

Yemen’s aviation sector continues to be a casualty of the ongoing conflict, with Yemenia Airways caught in a bitter tug-of-war between Houthi authorities and the internationally recognized government. On May 31, Yemenia management in Aden issued a circular prohibiting the acceptance or modification of tickets issued by the airline’s office in Sana’a. The ban came just three days after Israeli airstrikes destroyed Yemenia Airways’ last operational aircraft in Sana’a, following the destruction of three planes in a separate strike in early May. According to its Houthi-appointed director, initial losses at Sana’a Airport amounted to approximately US$500 million, with the damage assessment still underway. Houthi authorities have reportedly launched a new tax collection campaign targeting merchants in the districts of Al-Thawra and Bani al-Harith, with the stated aim of reconstructing the airport, threatening merchants with arrests if they fail to comply.

The Israeli attacks have put Sana’a airport completely out of service. As a result, the Yemenia office in Aden has closed the airport’s ticketing system and cut off Houthi access to future ticket sales revenue. The Sana’a-based General Authority of Civil Aviation and Meteorology condemned the ban, calling it an “irresponsible action that violates the laws regulating air transport” and a “new escalation of violence against civilians.” It demanded an immediate reversal to ensure continued air ticket services for citizens from airports across Yemen. The Yemenia branch in Sana’a also rejected the move, stating that tickets for Sana’a-Amman flights were never restricted to Sana’a offices but were available for reservations at all domestic and international outlets. It said that over US$2.5 million in revenue from Sana’a-Amman ticket sales had been deposited into the company’s Aden accounts in the first quarter of 2025, though a Yemenia spokesperson in Aden denied this. The Sana’a-based office offered apologies to passengers whose tickets were refused by Yemenia’s management in Aden, but did not offer to refund ticket holders.

Since March 2023, Yemenia has been operating under two competing managements: one in Sana’a affiliated with the Houthis, and the other in Aden aligned with the government. Tensions between the two escalated in June of last year when the Houthis seized three Airbus 320s and froze US$100 million in company funds. In retaliation, Yemenia Airways in Aden suspended withdrawals from its Sana’a accounts and temporarily stopped issuing tickets in Houthi-controlled areas, a move which was quickly reversed. Sana’a was the only airport providing international flights from Houthi-controlled territory, where 70 percent of Yemen’s population lives. It also served as a critical entry point for humanitarian personnel. The politicization of air travel by both sides leaves ordinary Yemenis stranded and hinders access to medical care and essential goods.

CBY-Sana’a Orders Financial Institutions to Halt Transactions with Al-Kuraimi Bank

On June 22, the Houthi-affiliated Central Bank in Sana’a (CBY-Sana’a) issued a circular demanding that all financial institutions immediately suspend transactions with Al-Kuraimi Islamic Microfinance Bank. Under the pretext of “guaranteeing customer funds,” the CBY-Sana’a said financial institutions must liquidate their balances with Al-Kuraimi Bank within 15 days. While the circular avoided direct identification, it was aimed at Yemeni banks, money exchange outlets, and financial transfer networks operating in Houthi-controlled areas. The announcement caused a surge of panic among the public and the bank’s clients, triggering a rush for cash withdrawals. The bank struggled to honor these requests, complicating its outstanding liquidity position. Escalating US sanctions have forced Yemeni banks to navigate a treacherous and complex environment. If they remain in Sana’a, they are vulnerable to US action – two have already been sanctioned for their alleged financial support to the Houthis. Operating from Sana’a also hinders their capacity to facilitate cross-border transactions, disrupts trade, and further isolates the country from the global financial system. It also increases the risk of Yemen being labeled a high-risk jurisdiction, which would jeopardize relationships with correspondent banks and further economic marginalization.

Banks have accordingly sought to relocate their main operations to Aden. This places them under the supervision of the CBY-Aden, limiting the CBY-Sana’a’s oversight. The Houthis’ punitive measures thus aim to preserve the financial centrality of Sana’a and the authority of its central bank. Al-Kuraimi is one of eight banks that the CBY-Aden publicly confirmed would relocate their headquarters to Aden. During a recent webinar organized by the Sana’a Center, the head of the CBY-Aden, Ahmed Ghaleb al-Maabqi, affirmed that many banks have made progress to meet the relocation requirements set out by the CBY-Aden, with three having fully complied.

Al-Kuraimi is Yemen’s largest microfinance institution, handling a significant portion of the country’s monetary flows and boasting a large client base. As of 2023, the bank had a staggering 91 percent of the country’s active microfinance depositors (3.3 million clients). It has also played a crucial role in facilitating humanitarian cash transfers, leveraging its wide geographic reach across Yemen.

The circular sets a dangerous precedent and could augur further measures to paralyze Al-Kuraimi and dismantle its large client base. Other banks trying to meet the CBY-Aden’s relocation requirements could face similar fates. Further action would threaten the solvency of the entire banking sector and destabilize the nation’s crumbling economy, with catastrophic ramifications.

Houthis Tighten Grip Over Economy Amid Sanctions and Airstrikes

Houthi authorities are utilizing legal and illegal measures as a show of power, particularly for their domestic audience, and to reinforce their control over the economy in areas under their control.

On April 23, a directive banning the import and sale of American goods marked the second Houthi attempt to restrict US goods, after a 2023 boycott list failed to gain traction due to Yemen’s dependence on American imports. Products already prevalent in Yemen and most likely to be affected by the new measures include vehicles from GMC, Ford, and Jeep, heavy equipment from Caterpillar, electricity generators from Cummins, and computers and other technology from Apple, Dell, and HP. US exports to Yemen totalled US$134.1 million in 2024, a 30 percent drop from 2023.

As part of efforts to promote “self-sufficiency,” the Houthis have been increasingly focused on localizing food production, manufacturing, and pharmaceutical industries, benefiting companies and networks affiliated with the group. On June 2, Houthi authorities announced a ban on the import of a wide range of commodities, including ready-made, canned, and liquid dairy products, nonnatural juices (mango syrup), mineral water, paper towels, ready-made sponges, iron and galvanized poles, hollow iron pipes and tubes, and products made of hanger iron, among other goods. Beyond bans and sanctions, Houthi authorities have continued economic exploitation and black market activity through intimidation, looting, and arbitrary taxation.

The millions of dollars of damage caused by intense US and Israeli airstrikes on Sana’a and other Houthi-controlled cities further weakened the electricity supply and had severe repercussions on local factories. The Bajil Cement Factory in Hudaydah was almost destroyed by Israeli strikes, halting production worth an estimated YR4 billion per month and putting more than 850 employees out of work. The Amran Cement Factory, employing approximately 1,500 workers, was also hit. The largest in Yemen, its revenues were estimated to be higher than YR8 billion per month. More than 10,000 families were reportedly indirectly dependent on the factory for their income. Attacks on the two plants have also affected prices: according to media reports, the cost of cement and building materials rose by up to 30 percent in Houthi-controlled areas.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية