The balance of power in the Middle East has been transformed in the past year and a half. For years, there was a widespread assumption that there existed a loose balance of terror between Israel and Iran. Analysts understood that Israel’s conventional military power, backed by the United States, was vastly superior to Iran’s depleted military. But the common view was that Iran’s unconventional assets – its missile and drone programs and its support for violent non-state armed groups – posed enough of a threat to deter Israel from attacking.

This perception led to the gradual development of unofficial rules of the game between the two sides, whereby each repeatedly attacked the other, but indirectly, and with sufficient restraint to signal a desire to avoid escalation. This fragile equilibrium has been upended by the wars that have followed the October 7, 2023, attack by Hamas. Israel’s devastating military campaigns in Gaza and Lebanon have severely weakened Hamas and Hezbollah, key members of the Iran-led Axis of Resistance. The only other state actor in the Axis, Bashar al-Assad’s Syria, collapsed in December 2024 after almost 14 years of civil war. Most devastatingly, Iran itself was soundly beaten by Israel in each of their three direct, increasingly intense military confrontations, first in April and October 2024 and then culminating in the 12-day war of June 2025.

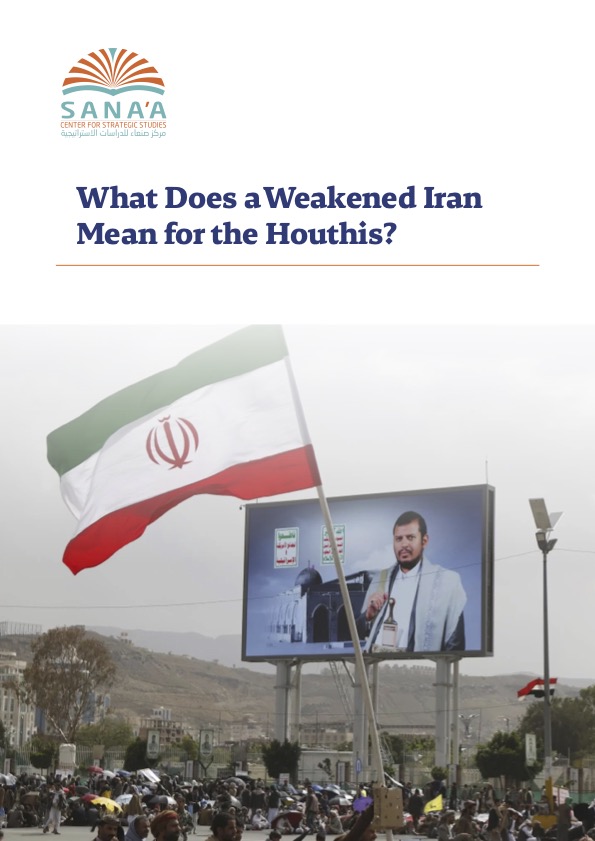

The Houthis represent the exception: they are the only Axis member whose power has grown. They are now an influential regional power with the ability to carry out missile and drone attacks on targets as far away as Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Their ascendance has been the result of a combination of external factors (Iranian assistance) and domestic dynamics (the weakness of their opponents in the internationally recognized government). In this context, what does the weakening of the Islamic Republic of Iran mean for the Houthis?

The most consequential question is whether a weakened Islamic Republic will decrease its support for the Houthis. This is far from a given; in fact, it is plausible that a chastened Iran will double down on its support now that the Houthis have emerged as its most powerful non-state partner. Iran has lost important battles against its Israeli and American rivals, and many of its key partners are down. If anything, Tehran needs the Houthis more than ever before. Importantly, its support for the Houthis has represented a financial investment estimated to be in the low hundreds of millions of dollars per year. This relatively modest support can be sustained indefinitely, even taking into account Iran’s fragile economic and geopolitical state. Crucially, this limited investment has brought the Islamic Republic tremendous returns, significantly boosting its influence on the Arabian Peninsula. An isolated and contained Iran cannot afford to lose this asset. The most likely scenario, therefore, is that Tehran will continue and possibly intensify its support for the Houthis. Recent interceptions in the Red Sea of advanced drone technology destined for the Houthis tend to support this hypothesis.

That said, a decline in Iranian support for Houthi missile and drone programs would represent an important strategic setback for the group. While their large weapons stockpiles would allow them to absorb the loss of Iranian support in the short to medium term, their power would erode over time. The Houthis could sustain some of their shorter-range and less advanced missile and drone capabilities by continuing to develop their indigenous production, but it is their ability to strike deep into Saudi territory and target the UAE that allows them to constrain Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s room for maneuver in Yemen. A decrease in these capabilities, even if only partial, could gradually change the balance of power on the Arabian Peninsula to the Houthis’ disadvantage. This could increase the incentive for Saudi Arabia and the UAE to ultimately support a new ground offensive against the Houthis. It would also represent an important turning point: they have been reluctant until now for fear of Houthi retaliation.

A cut in Iranian support would push the Houthis to intensify their efforts to diversify their partnerships, notably with Russia and China. Both have been willing in recent years to deepen ties with the movement, which holds de facto authority in Yemen’s capital and shares their opposition to the hegemony of the United States. At the same time, there are limits to how much Beijing and Moscow would be willing to support the Houthis, especially with weapons. Crucially, both states value their growing ties with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and would be unwilling to jeopardize these relationships.

The most likely scenario is that the Islamic Republic – which has suffered significant losses but is not on the verge of collapse – will continue, and possibly increase, its support for the Houthis, who have emerged as the most powerful non-state member of the Axis of Resistance. However, should this support decrease, the longer-term impact would be disadvantageous to the Houthis’ regional influence. Yet they would likely remain the dominant actor inside Yemen, given the weakness of their adversaries and their own domestic weapons production. That is why it is now more essential than ever for the United States and its regional allies and partners to increase their support for the internationally recognized government and double down on efforts to interdict the smuggling of Iranian weapons and weapons parts to the Houthis.

This analysis is part of a series of publications produced by the Sana’a Center and funded by the government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The series explores issues within economic, political, and environmental themes, aiming to inform discussion and policymaking related to Yemen that foster sustainable peace. Any views expressed within should not be construed as representing the Sana’a Center or the Dutch government.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية