Houthis Remain Resilient As US Terminates Air Campaign

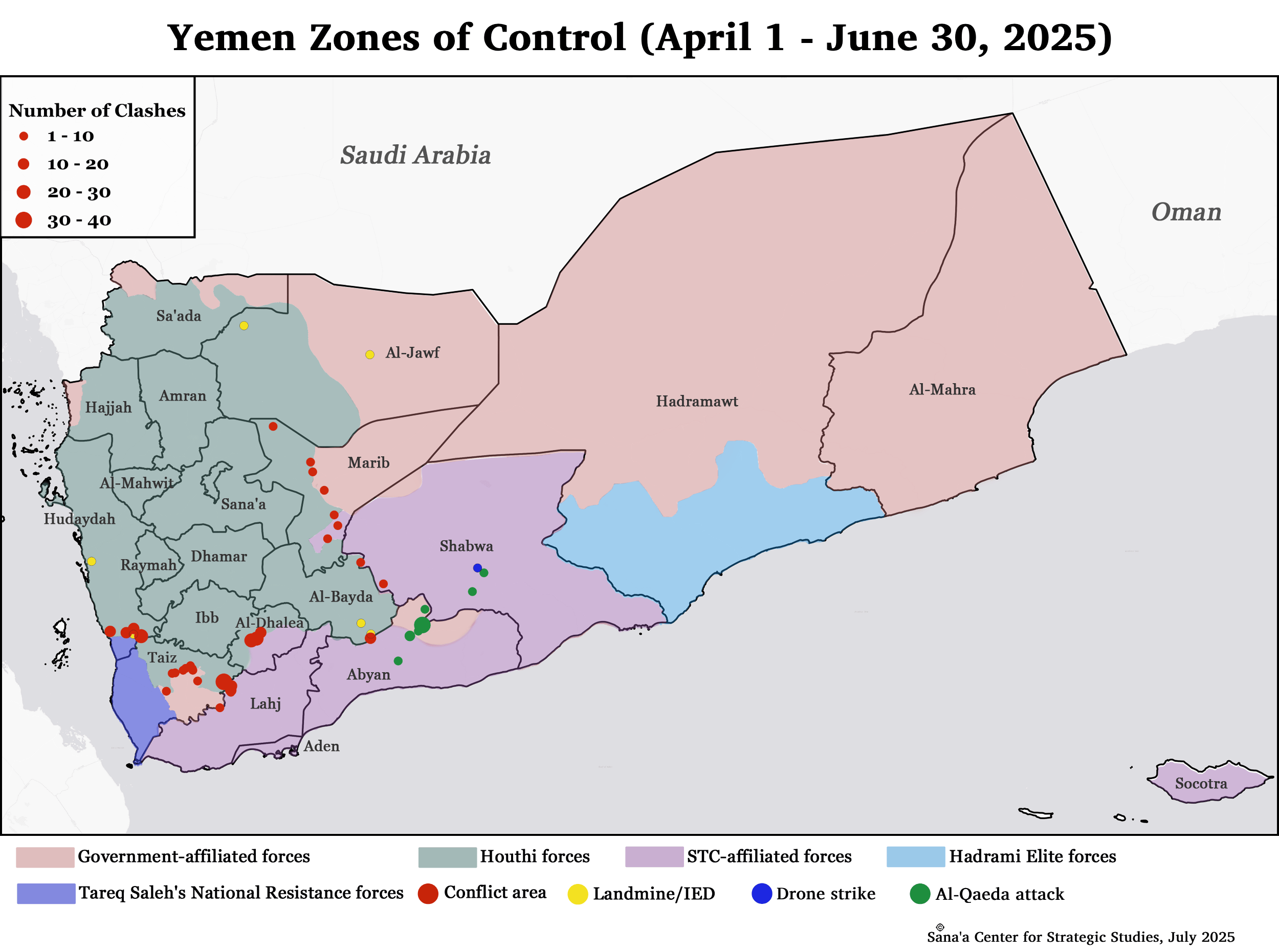

Spring 2025 marked a turbulent new phase in Yemen’s conflict, as the region experienced one of its most volatile and contradictory periods in recent years. In the past three months, an intensified US air campaign, multiple Israeli airstrikes, a rumored anti-Houthi ground offensive, and direct military confrontation between Israel and Iran deepened regional instability and emboldened the Houthi group (Ansar Allah) as it seeks to position itself as the vanguard of the Axis of Resistance in the defense of Gaza against Israel and its Western allies.

In Yemen, much of the early spring was defined by Operation Rough Rider, the 52-day US military campaign to degrade Houthi capabilities and secure maritime shipping. Launched on March 15, the operation rapidly surpassed efforts to weaken the Houthis under former President Joe Biden, becoming one of the most sustained and intensive bombing efforts in Yemen since the early years of the Saudi-led coalition. US forces (with the help of British fighter jets on one occasion) carried out roughly 300 attacks across 13 governorates,[1] targeting Houthi leadership and military infrastructure, reportedly with over 1,100 airstrikes.

Despite early hopes for success and promises that the Houthis would be “completely annihilated,” the operation’s efficacy quickly came into question. A US defense contractor estimated that Washington had spent at least US$1 billion in just the first 30 days of operations, raising questions over Rough Rider’s long-term strategic and financial viability. The loss of two US$67 million F/A-18 Super Hornet fighter jets from the USS Harry S Truman (one from a landing gear malfunction and the other lost overboard while maneuvering under Houthi fire) added to growing concerns about the campaign’s toll.

Mounting civilian casualties further complicated the picture. Houthi authorities estimated that more than 200 civilians were killed in total, as airstrikes hit a number of civilian areas and residential neighborhoods. The high proportion of civilian deaths, which some estimated may have exceeded the combined casualties from the previous 23 years of US action in Yemen, quickly drew criticism from human rights groups. Among the most controversial incidents were the bombing of a purported pre-Islamic archaeological site on April 9, the destruction of an alleged ceramics factory on April 13 (the Houthis reported six killed, 13 injured), and an attack on a residential neighborhood in Hudaydah on the same day (the Houthis reported 13 killed, 15 wounded).[2] On April 28, a likely US airstrike struck a migrant detention center in Sa’ada, killing 68 people and injuring at least 48 others. US officials stated at the time that they were aware of the incident and promised to investigate the matter, but did not provide any further information.

As military costs and casualty numbers rose, so too did political pressure in Washington. The downing of seven US MQ-9 drones over Yemen in six weeks, coupled with persistent Houthi missile and drone attacks on Israel and US naval assets in the Red Sea, raised doubts over the campaign’s strategic return. In late April, President Trump asked for a damage assessment, reportedly frustrated with the campaign’s results and timeline. While Pentagon officials confirmed that the campaign had inflicted limited damage on Houthi weapons stockpiles, intelligence reports suggested that the group had relocated significant stores of munitions underground and was capable of regenerating lost capacity within months. Any serious degradation of Houthi military capabilities would likely require a prolonged and resource-intensive effort.

Consequently, President Trump officially pulled the plug, announcing on May 6 that Houthi leaders had “capitulated” and requested an end to the strikes. The Houthis, on the other hand, framed the cessation of attacks as their own strategic victory, asserting that US forces had “backed down.” Omani mediators later clarified that they had brokered a ceasefire, wherein both groups would agree to stop targeting one another, and with the Houthis promising to halt attacks on American commercial and military ships. US officials later told Reuters that the Houthis had reached out to US allies in the region in search of a deal, and claimed that Iran had facilitated negotiations. Sources told the Sana’a Center in mid-April that the US administration had sent conditions to the Houthis via Omani mediators.

The decision to end the air campaign may have also been influenced by President Trump’s state visit to Riyadh on May 13. Tensions were reportedly high in the days preceding the trip, with the Houthis warning against Trump’s visit and threatening vaguely that US action in Yemen could “impact” his visit. Saudi Arabia reportedly pressed US officials to avoid “playing with fire” by hitting Yemen during the visit. On May 17, the USS Harry S Truman departed the CENTCOM area of operations, ending eight months of deployment in the Red Sea and confirming that the US campaign was indeed over.

Although Operation Rough Rider was one of the most intense US military campaigns in Yemen in nearly a decade and the first major foreign military action of Trump’s second term, it fell short of delivering a decisive blow to Houthi capabilities. The Houthis’ military apparatus remains largely intact, and the group has continued to launch missiles and drones toward Israel. In a confrontation where survival alone is a form of success, the group’s ability to threaten US warships without annihilation has been framed as a major tactical victory. The campaign not only demonstrated the limited capabilities of an air campaign to weaken a group like the Houthis but, more importantly, highlighted the group’s capacity to absorb losses, adapt its tactics, and reposition weapons stores.

Rumored Anti-Houthi Ground Offensive Fails to Materialize

Amid early reports of Houthi degradation under the US-led air campaign, speculation mounted over a potential large-scale ground offensive by government-aligned forces into Houthi-controlled territory. Preliminary reports suggested that as many as 80,000 troops were being mobilized for a possible advance on Hudaydah, with ambitions extending to the recapture of the strategic port city and even a renewed push toward Sana’a.

However, momentum behind the proposed offensive had waned by mid-April, as no actor appeared willing to take the lead. Government forces made it clear they were not willing to proceed without substantial external backing, either from the United States, Saudi Arabia, or the UAE. Washington, for its part, showed no appetite for deeper involvement, while Riyadh maintained a deliberately ambiguous position.

By early May, it was evident that the campaign had been shelved entirely. Beyond the logistical problems and growing factionalism already plaguing the anti-Houthi coalition, broader questions emerged among its Gulf sponsors over the political endgame: namely, who would shape Yemen’s post-conflict order if the Houthis were actually forced from Sana’a. Disagreements between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, particularly over the balance of influence between Islah, the Southern Transitional Council (STC), and Tareq Saleh’s National Resistance, further complicated the picture.

As with the US air campaign, the abandoned idea of a major ground offensive has likely reinforced Houthi propaganda that God has chosen the group to withstand foreign threats. The group has consistently framed such military withdrawals or failures of their rivals as evidence of its divine mandate and military superiority — a narrative central to its political legitimacy and sectarian dogma.

Houthi-Israel Confrontation Intensifies

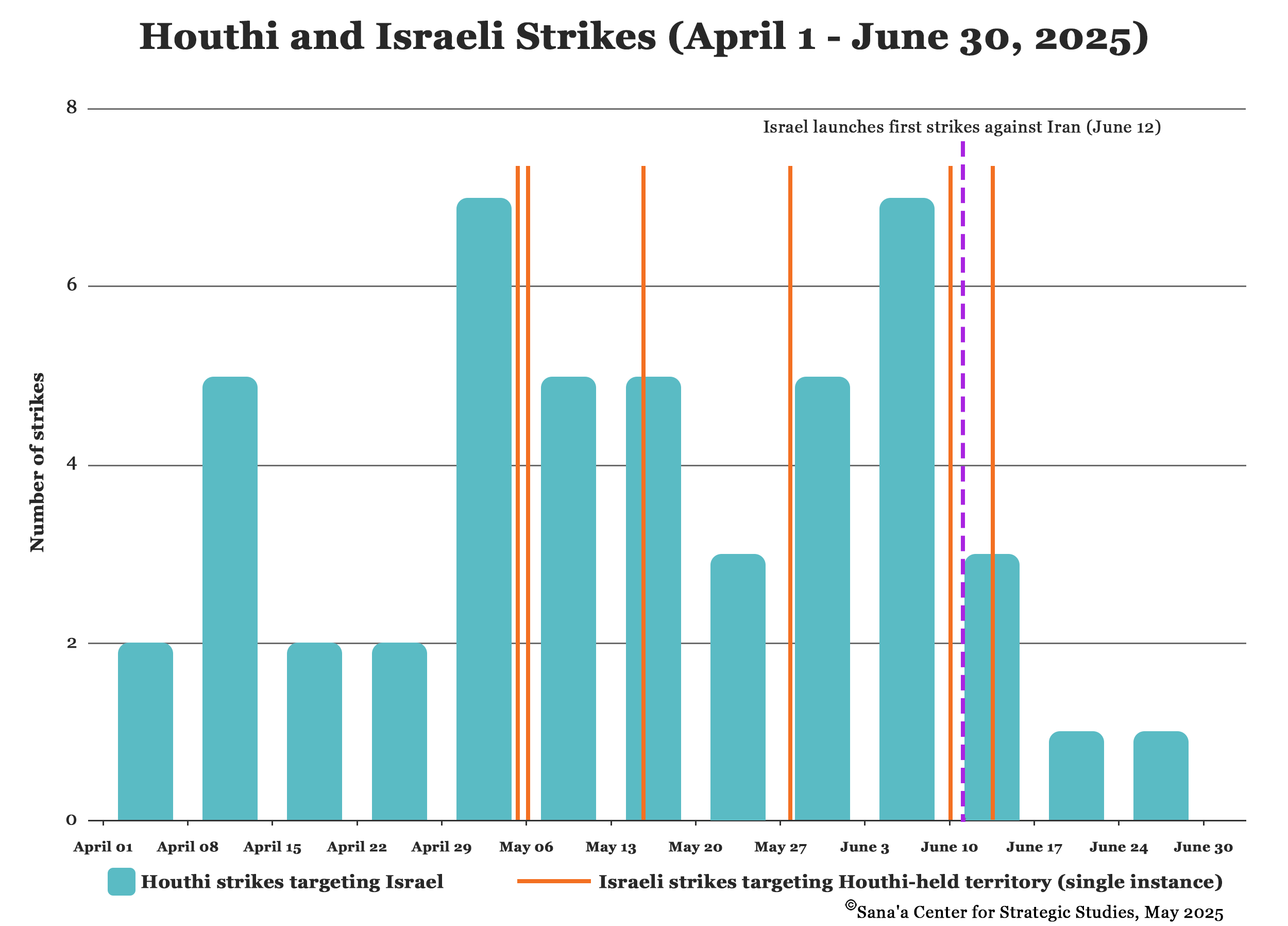

On May 4, a Houthi missile hit near Israel’s Ben Gurion Airport after bypassing a long-range Arrow interceptor and THAAD missile defense system. The missile is one of only a handful to evade Israeli defenses since attacks began in November 2023, along with several drones. Although no major infrastructure was damaged, the attack forced the airport to close for several hours and caused several airlines to temporarily suspend operations.

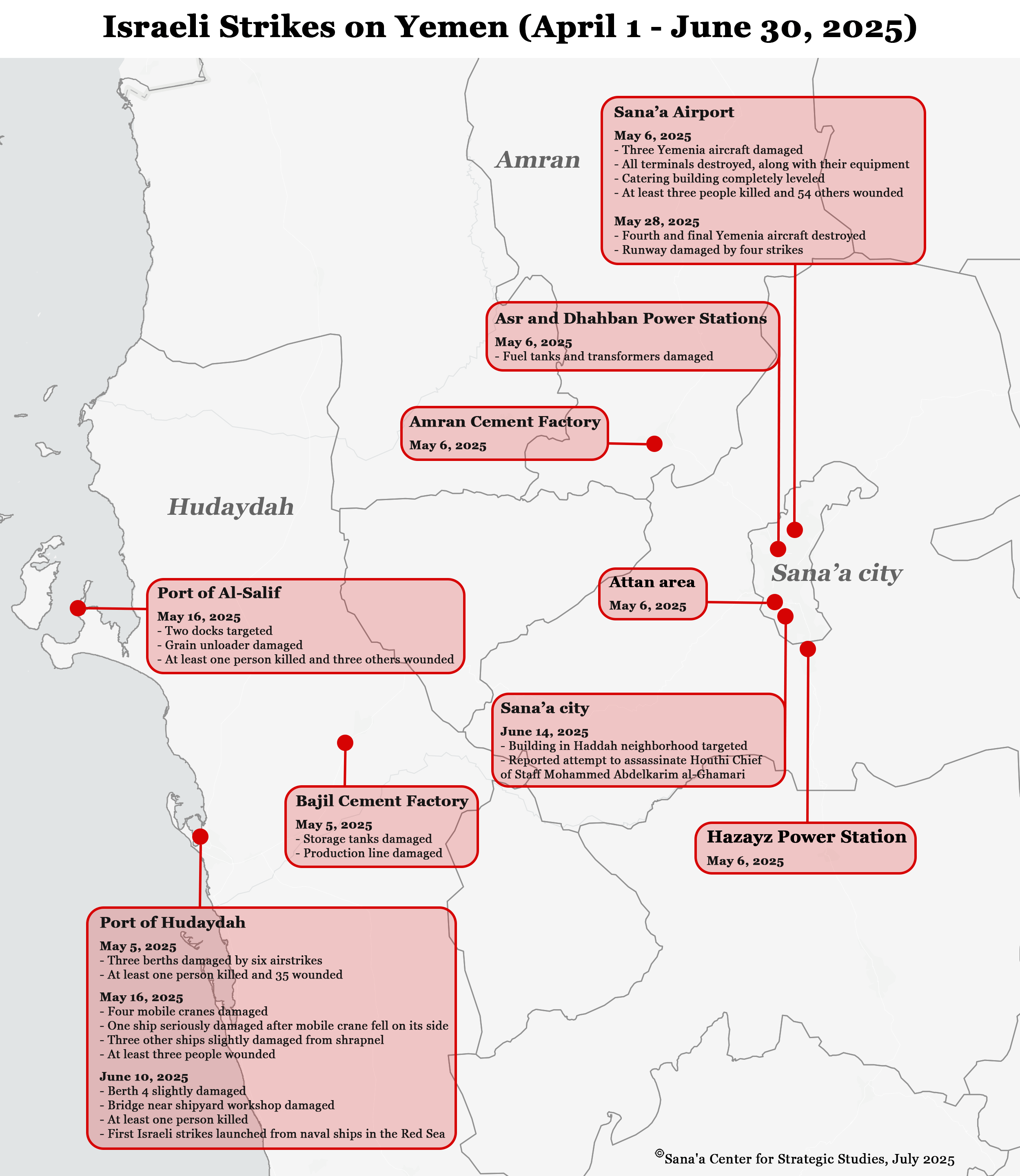

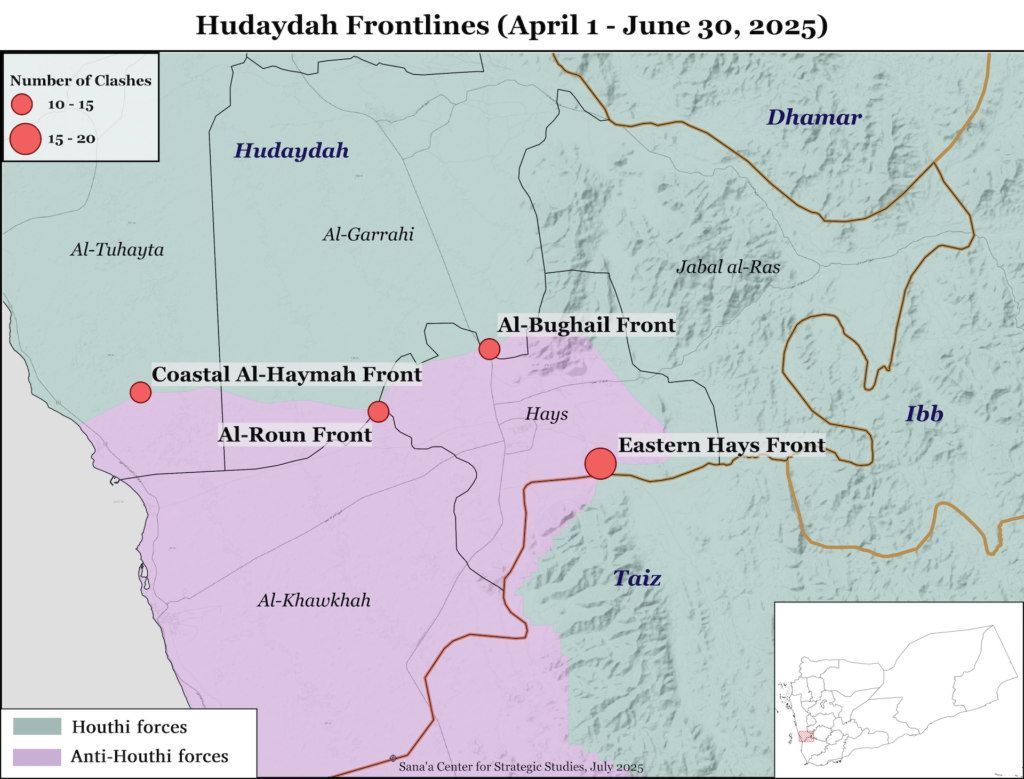

In response, Israel launched a series of strikes on May 5 that targeted Houthi infrastructure in Hudaydah. More than 20 Israeli aircraft took part in the initial attack, targeting the port of Hudaydah and a cement factory in nearby Bajil district, northeast of Hudaydah city. The following day, a second round of strikes targeted Sana’a International Airport, electricity infrastructure across the Houthi-held capital, and a cement factory in Amran city. Damage to the airport was significant: runways and passenger terminals were destroyed, along with three Yemenia aircraft. The airport’s director, Khaled al-Shaief, estimated that the damage amounted to at least US$500 million.

Undeterred, Houthi strikes continued, with the group claiming to have targeted Israel six times the following week. On May 11 and 14, Israel issued warnings to civilians to evacuate the ports of Hudaydah, Ras Issa, and Al-Salif “until further notice.” The response finally came on May 16, when Israeli strikes again targeted key maritime infrastructure at the ports of Hudaydah and Al-Salif. Several mobile cranes were damaged at the port of Hudaydah, along with four ships docked at the time of the attacks, while two docks and a grain unloader were destroyed at Al-Salif. Following the airstrikes, Israeli Defense Minister Israel Katz stated that Israel would “hunt and eliminate” Abdelmalek al-Houthi, marking the first time it has openly declared its intention to assassinate the top Houthi leader.

Despite heavy damages to its ports and airports, the group continued to escalate its rhetoric: on May 20, the Houthi Higher Operations and Coordination Command (HOCC) announced an air and naval blockade of Haifa, an expansion of their earlier symbolic threat to impose an aerial blockade on Israel. The head of the Houthi Supreme Political Council, Mahdi al-Mashat, later warned that commercial flights over Israel would be legitimate targets. Such threats and claims, along with intimations that the group was developing multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), likely had little substance.

On May 28, Israeli forces destroyed the fourth and last remaining civilian plane at Sana’a airport. Four strikes also damaged the runway. The Yemenia Airways flight was reportedly scheduled to take pilgrims to Saudi Arabia for the annual hajj pilgrimage. The airline released a statement following the attack, saying it had suspended all flights to and from Sana’a until further notice. Israeli messages after the attack promised future damage to Houthi ports, mocking Houthi rhetoric with threats of a “naval and aerial blockade.”

Such promises were fulfilled on June 10, when Israel launched a third strike on the port of Hudaydah. The attack, which utilized Sa’ar corvette warships, was the first Israeli naval assault during the conflict. Like other attacks, the raids were a direct response to Houthi missile and drone attacks on Israel, and targeted shipping berths and port infrastructure that had been repaired since the May attacks. Despite Israeli warnings to evacuate the port before the attack, five port workers were reportedly injured in the attack, and one truck driver was killed.

Like the American airstrikes under President Trump, repeated Israeli attacks on Houthi ports and airports have yielded mixed results. On one hand, the strikes succeeded in damaging and destroying critical infrastructure, particularly at Sana’a airport and the various Houthi-held ports. Such losses are already tangibly impairing the group’s ability to import food and smuggle weapons and fuel into Hudaydah, but come with a heavy humanitarian cost. The strikes have also effectively trapped many of the 25 million Yemenis living in Houthi-controlled territories, as Sana’a airport was the main remaining link to the outside world. However, Israel’s retaliatory strike policy has failed to deter the Houthis as they continue to repair port infrastructure, relocate weapons, and maintain a steady, if reduced, pace of missile and drone attacks.

Houthis Scale Back Attacks Amid Israel-Iran Conflict

Direct Israeli airstrikes against Iran on June 12, which targeted senior Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) commanders and nuclear infrastructure, added a new dimension to the already strained situation in Yemen. The outbreak of open conflict between Israel and Iran likely put the Houthi leadership in a difficult position, as they struggled to balance their ambitions as an emerging Axis of Resistance leader with the need to protect local and regional interests against an unpredictable Israel. The result was a noticeably restrained military posture, in which Abdelmalek al-Houthi promised to be “partners in the situation as much as we can be.”

As such, the group immediately scaled its sustained missile and drone launches. Throughout the two-week conflict, only one attack was launched against Israel, on June 15, in “coordination with Iran.” The Houthi strikes came a day after Israeli jets bombed Sana’a city in an attempt to assassinate Houthi Chief of Staff Abdelkarim al-Ghamari. Journalists in Sana’a later reported that several senior military officials, including Al-Ghamari, had been wounded in the attack, but not killed.

Throughout the conflict, the Houthis maintained close contact with Tehran in anticipation of a possible escalation. A June 20 media report claimed that the Iranian ambassador to the Houthis, IRGC official Ali Mohammed Rezaei, had relocated from Sana’a to Hudaydah, accompanied by IRGC commanders allegedly tasked with overseeing potential military operations. Missile launchers and drones were reportedly repositioned in several residential areas across Hudaydah governorate.

Whatever plans the Houthis may have prepared ultimately proved unnecessary. On July 23, President Trump announced a tenuous ceasefire between Israel and Iran, following US strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities two days prior. For the Houthis, such a statement came at an opportune time, freeing them from following through with threats to resume targeting American naval ships if the US entered the conflict, made only two days earlier. The subsequent de-escalation led to a relative calm in Yemen, with the Houthis refraining from further strikes in its immediate aftermath.

On June 28, reports surfaced that the Houthi leadership was in Baghdad, along with representatives from Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Hezbollah, and Iranian-backed Iraqi militias, to attend meetings organized by Iran’s IRGC to “reset” its regional network. The meeting was likely a prime opportunity for the Houthis to underscore their expanding role and influence within the Axis, especially in light of the major degradation of Palestinian factions, Lebanese Hezbollah, and Iran in the post-conflict period.

Houthi actions during the “12-day war” demonstrated that, while the group remains a committed partner to Tehran, its operational role is geographically and tactically constrained, particularly to the Arabian Peninsula, the Red Sea, and surrounding maritime corridors. As of yet, the group remains unable to pose any serious tactical threat to Israeli assets beyond commercial shipping, meaning its capabilities, while disruptive, are unlikely to alter the strategic balance in Tehran’s favor in future confrontations.

Paranoia in Sana’a

In the weeks immediately following the détente between Iran and Israel, the Houthis continued to hold off on their attacks, turning attention instead to internal security, as the same fears that led to the arrest of hundreds of alleged Mossad agents in Iran struck the Houthi-held capital. For weeks, the group carried out a crackdown in an attempt to weed out potential threats and stifle “internal treason.”

Local sources told the Sana’a Center that the group has prevented non-Yemeni staff at international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) from leaving their residences or meeting in public and barred them from communicating with political figures and military officials. Meanwhile, the Houthi-affiliated Ministry of Interior banned qat chewing in the streets in Sana’a city after 1 a.m. – a move believed to be aimed at reducing nighttime activity as a pretext to track civilian movements.

But any hopes that the Houthis would refrain from further attacks on Israel were soon dispelled when, on June 28, the group launched a ballistic missile toward the Israeli city of Be’er Sheva (Beersheba), which was downed by Israeli defenses. Another strike targeting Ben Gurion Airport followed on July 1, along with a claim that the group had quietly launched several drone and missile attacks in previous days without providing details. As with other launches, the attacks drew immediate threats from Israeli Defense Minister Israel Katz, who warned that, “The law of Yemen is as the law of Tehran.” His remarks were matched by US Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee, who posted on X that, “Maybe those B2 bombers need to visit Yemen!” in a reference to US airstrikes on Iranian nuclear facilities.

Renewed Houthi attacks against commercial shipping resulted in the sinking of two vessels on July 6 and 7, and may have brought the situation back to square one. The operation, which left at least five crew members dead and another 11 missing, is the Houthis’ boldest move yet and signals a deliberate return to maritime disruption after seven months of calm. What remains unclear is how the US will respond. The American air campaign against the Houthis ended in May with an understanding that the group would refrain from targeting US-linked commercial shipping, according to terms disclosed to the Sana’a Center — yet the agreement was silent on Houthi attacks linked to Israel. This ambiguity leaves open the question of whether Washington will tolerate a resurgent Houthi maritime threat, or whether renewed attacks will trigger another cycle of sustained US- or Israeli-led military action. Regardless, the Houthis appear to be testing the limits of American and Israeli deterrence, not only sending an important message to Netanyahu and Trump while the former was visiting Washington, but also betting that a calibrated escalation at sea will boost their regional standing without provoking an overwhelming retaliation.

Other Developments

April 17: The Financial Times reported that a Chinese company with links to the country’s army was supplying the Houthis with satellite imagery to help its targeting of US Navy and commercial vessels. US officials said they raised the issue in private conversations with the Chinese government but were ignored. China has previously called for the Houthis to end attacks on shipping in the Red Sea.

May 22: More than 60 civilians were killed or wounded and dozens of homes destroyed in an explosion at a Houthi weapons depot in eastern Sana’a, near the airport. The site, which was clandestinely built near a residential area, reportedly contained air defense missiles and other explosives, including C4 and potassium nitrate. Government officials suggested the explosion was caused by a failed Houthi missile launch, but some media outlets contested this claim. Following the incident, Houthi forces launched a crackdown on civilians who filmed and shared footage of the blast or the aftermath at local hospitals.

May 23: The fifth round of US-Iran talks took place in Rome. Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi, Omani Foreign Minister Badr Albusaidi, and Qatari Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Mohammed al-Thani held talks days earlier in Tehran on May 18. Talks were later suspended indefinitely after US airstrikes in June.

June 2: The Tulip BZ, a Comoros-flagged vessel owned by Lebanon-based Zaas Trading Company, entered Hudaydah’s port of Ras Issa after departing from Oman’s Duqam port, according to local sources. The Tulip BZ was sanctioned in April by the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) after it allegedly delivered petroleum products to the port on behalf of Iran.

June 6: Houthi authorities raided Save the Children’s offices in Sana’a, Amran, Hajjah, Sa’ada, Hudaydah, and Ibb, seizing an estimated US$4 million in supplies. Save the Children had previously decided to suspend operations in Houthi-controlled areas over the increasingly unstable security situation and restrictions on its operations, terminating around 400 employee contracts.

June 12: Houthi authorities detained 54 people across Sana’a during raids targeting Starlink satellite users. In April, Houthi authorities declared Starlink devices illegal and demanded residents surrender the technology, out of fear that it would be used for espionage. Authorities confiscated dozens of Starlink-affiliated electronic devices and imposed fines on violators.

June 16: STC-affiliated forces stationed at the Al-Alam checkpoint, located near the border of Abyan, Lahj, and Aden governorates, prevented demonstrators from Abyan from entering Aden to protest the disappearance of pro-government military officer Ali “Ashaal” al-Jaadani. Demands for justice for Al-Jaadani, who was allegedly abducted by STC-aligned security forces in 2024, were reignited after a southern activist died after being released from an STC-run detention center.

June 29: Hadramawt Deputy Governor and tribal leader Amr bin Habrish issued an order appointing leaders to his Hadramawt Protection forces, whose formation he had announced in December.

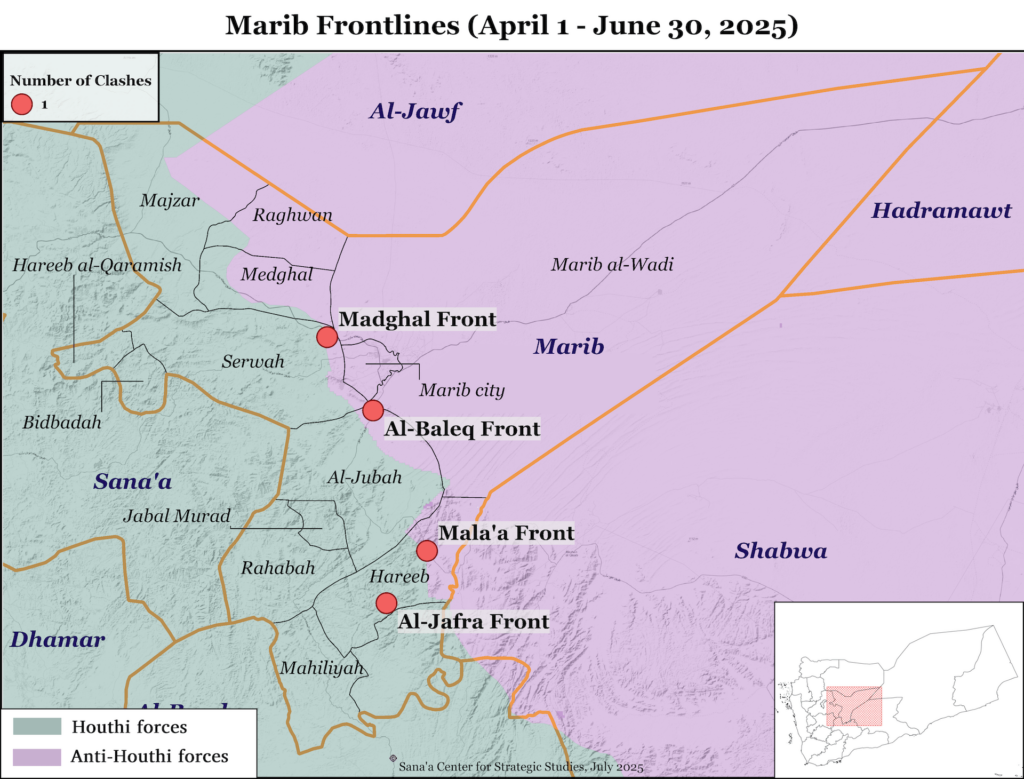

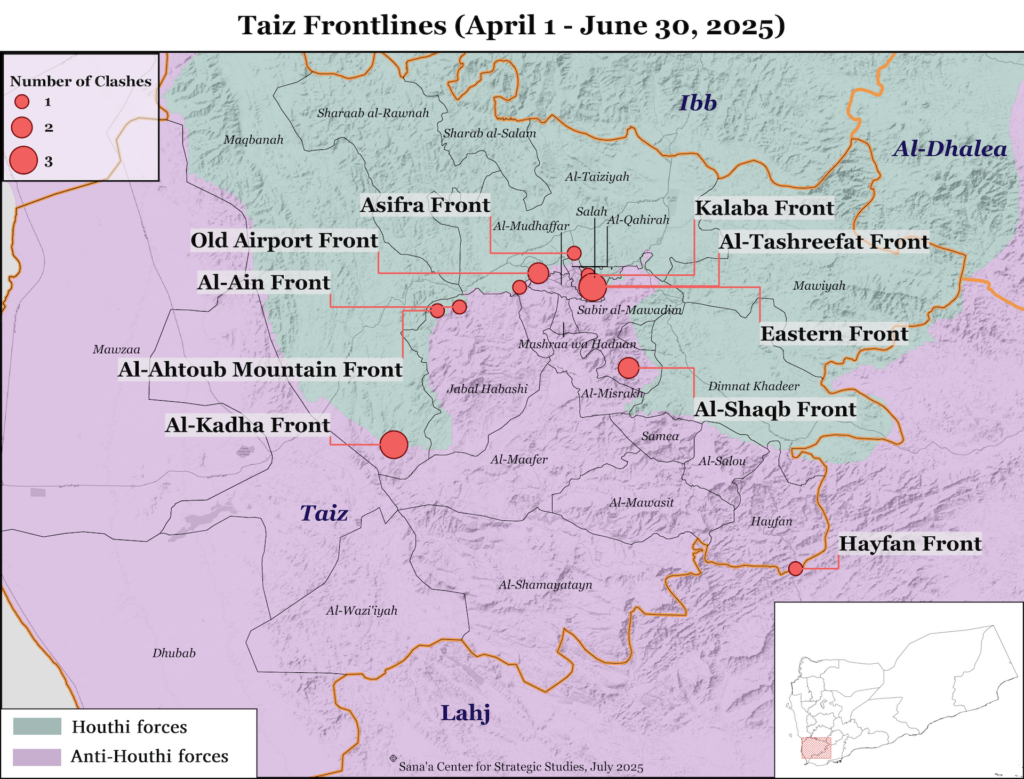

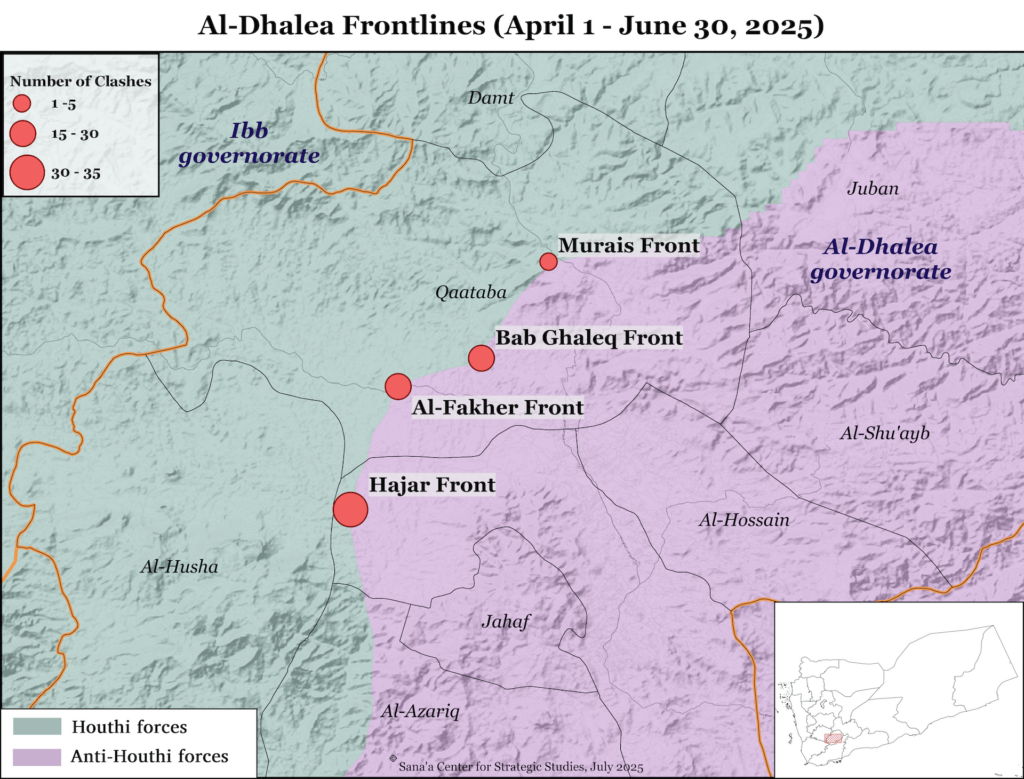

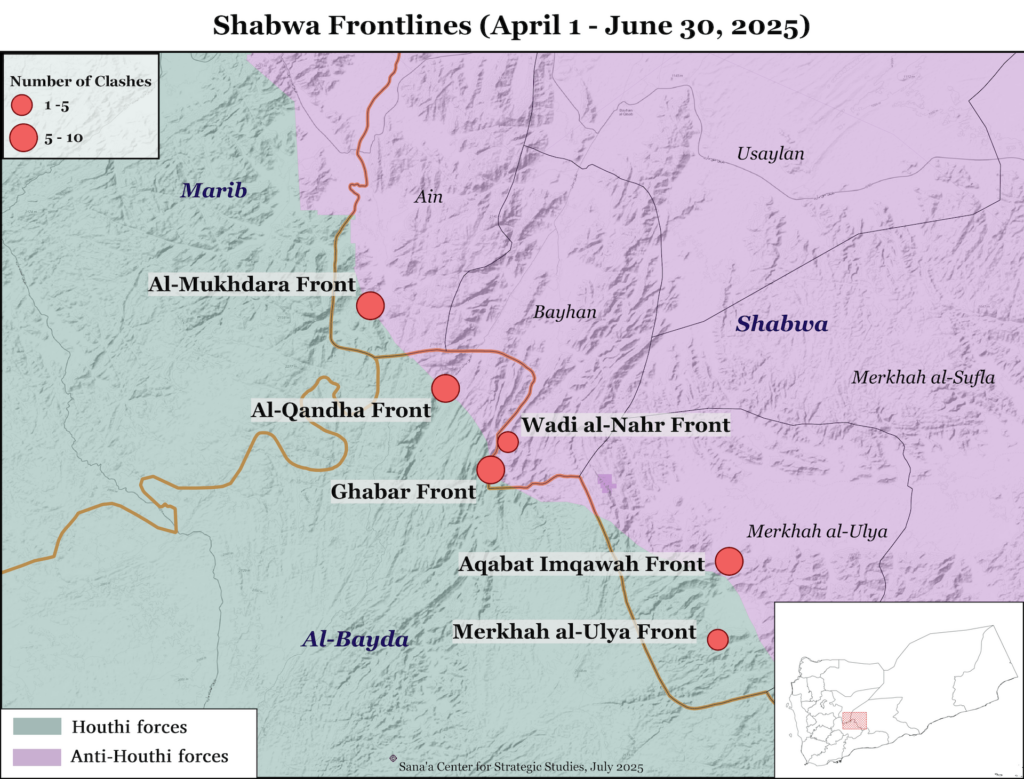

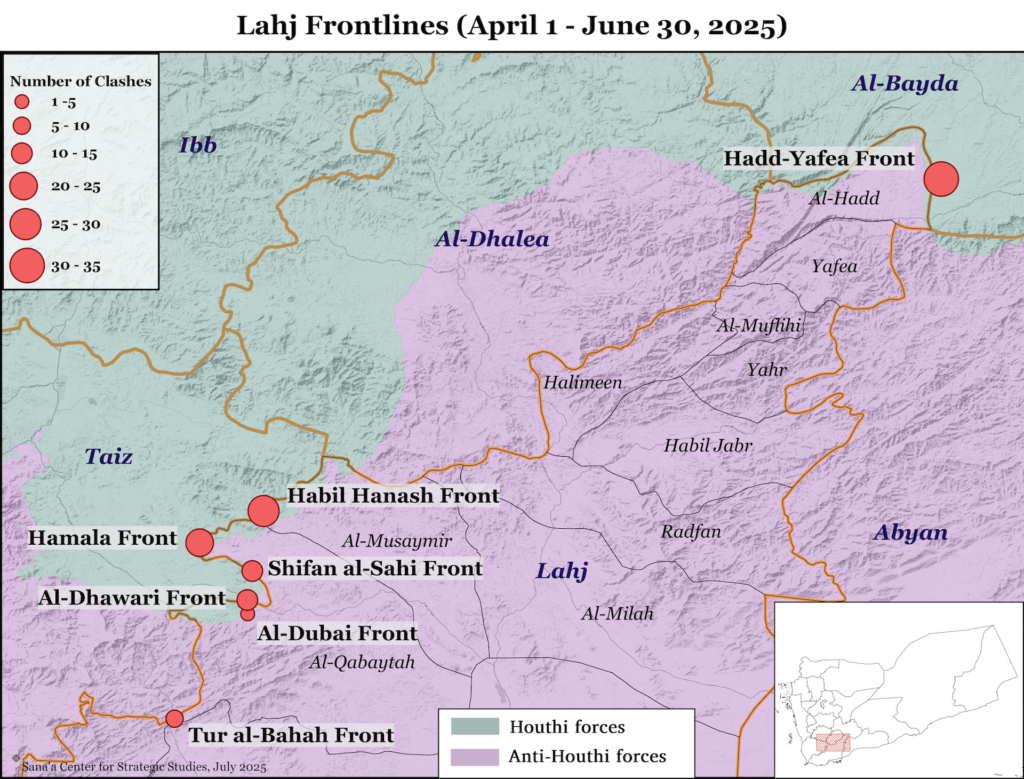

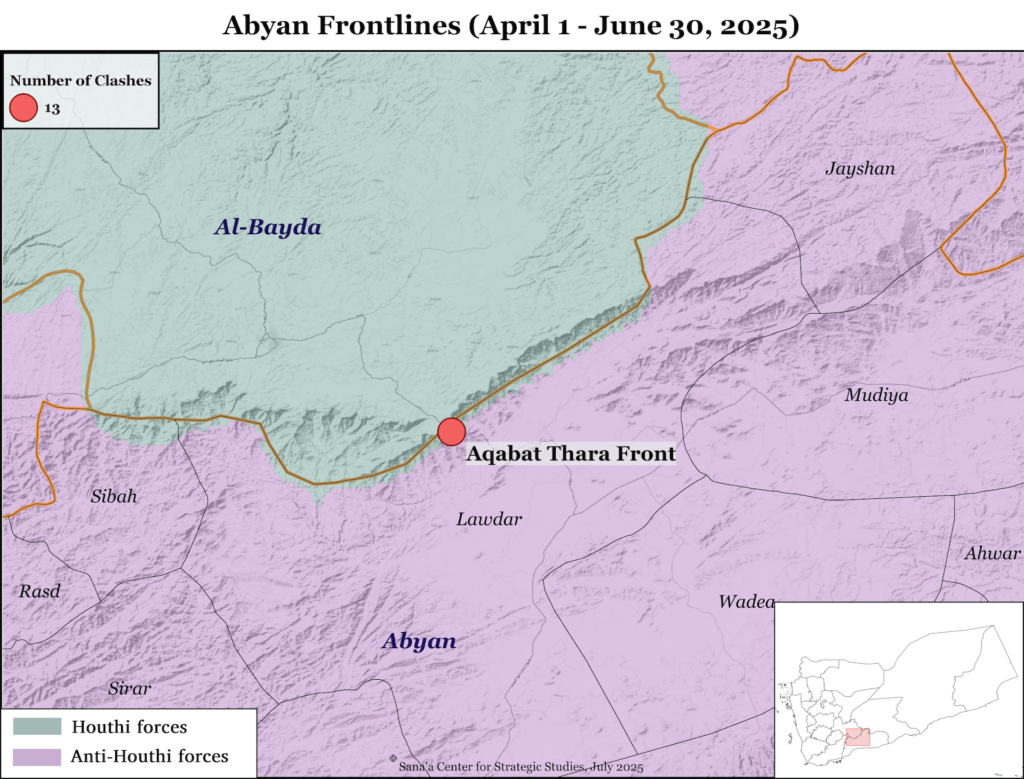

Frontlines

- Based on local reports, Houthi-affiliated media, government-affiliated media, and international media reports.

- It should be noted that the Houthis have a long history of converting civilian spaces, particularly factories and workshops, into military structures, often used for weapons production and storage.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية