Bin Breik In as Prime Minister After Bin Mubarak Resigns

On May 3, Yemen’s embattled Prime Minister Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak resigned after just over a year in office, following months of clashes with Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) chief Rashad al-Alimi, as well as other PLC and cabinet members. Finance Minister Salem bin Breik was immediately named as his replacement.

Bin Mubarak said his resignation stemmed from his efforts to assert his constitutional authority to overhaul the cabinet, an endeavor which was stymied by the PLC. He clashed repeatedly with Al-Alimi over his attempt to appoint 12 new ministers and resisted pushes by the Southern Transitional Council (STC) to place loyal deputies in ministries. On March 7, only three ministers attended a cabinet meeting called by Bin Mubarak at Al-Maashiq Palace in Aden, with 21 others boycotting, signaling how isolated he had become within the government. Ultimately, Riyadh, the PLC’s principal patron, sided with Al-Alimi. By the spring, Saudi officials had grown convinced Bin Mubarak was more trouble than he was worth. His departure cleared the way for the PLC to drop its opposition to STC demands for deputy positions. However, the question of a cabinet reshuffle will not go away – while it technically remains a constitutional requirement, Bin Mubarak’s predecessor, former Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed, was also prevented from appointing ministers of his choice.

The selection of Bin Breik was largely about optics and balance. A southerner from Hadramawt, he fits the formula of maintaining an inclusive government while minimizing STC grievances about marginalization. His main task is clear: avoid confrontations with the PLC and keep the fragile coalition afloat. Yet, even before formally taking office, Bin Breik made it clear that he wanted the governor of the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden), Ahmed Ghaleb al-Maabqi, replaced. The PLC’s economic chief, Hussam al-Sharjabi, has been floated as a possible successor, but some object to his minimal economics background and perceived Saudi loyalties.

The appointment of a new prime minister does not resolve the government’s deeper problems: a paralyzed economy, limited Saudi funds, and the ongoing Houthi threat that has halted oil and gas exports. Bin Breik initially delayed his return to Aden as part of an unsuccessful attempt to convince Riyadh to deliver financial aid—vital for paying public sector salaries and restoring basic services. While Saudi Arabia drags its feet on funding, only fighters based on the frontlines continue to receive payment. Civil servant salaries have gone unpaid since April, sparking street protests.

For now, Bin Breik retains the finance portfolio alongside his new post, a vacancy which multiple candidates have reportedly turned down, including Al-Maabqi and Al-Sharjabi. Meanwhile, lingering tensions within the PLC continue to stall appointments. A dispute persists between Al-Alimi and PLC member Tareq Saleh, who leads the National Resistance forces, over the post of deputy interior minister. Saleh wants one of his military commanders from Al-Makha, Mujahid al-Hizwara, while Al-Alimi prefers seasoned bureaucrat Mohammad al-Zalab. Saleh remains one of the few PLC figures actually based in Yemen.

Some positions appear closer to being resolved. Planning Minister Waed Badhib may shift to the telecommunications post, freeing his current ministry for Abdullah Abou Houria, Saleh’s deputy in the National Resistance’s Political Bureau. Former Prime Minister Ahmed bin Dagher, now the Shura Council head, has been lobbying in Riyadh and Washington to maintain his political relevance and currently leads the fragile coalition of parties, dubbed the National Political Bloc, which the US helped assemble last year.

Al-Alimi tried to placate the STC in his May 21 unification speech, framing the South’s grievances as central to any lasting solution. He emphasized that the failures of unification marginalized southerners and that the “Southern Question” must be addressed fairly. For the STC, which has stayed largely silent during the protests, Al-Alimi’s speech provided a convenient distraction. Still, the group’s leaders have avoided addressing public anger directly, instead appealing to the UN and foreign powers for urgent help—a familiar, often fruitless, tactic.

The underlying dysfunction in the government is structural. The PLC’s members answer not to voters but to Saudi and Emirati patrons. The council has still not formalized its bylaws, leaving lines of authority unclear. The cabinet is effectively neutered by the PLC’s dominance and Saudi-Emirati gatekeeping. Prime ministers are handpicked in opaque deals with no clear mandate, no political platform, and no power to choose their ministers. Bin Mubarak’s downfall shows the limits of pushing back. There is little confidence Bin Breik will prove more effective. His extended stay in Riyadh to wait for new funds signaled the weakness of his hand, and his return empty-handed to Aden on June 1 points to a government hobbled from the start.

Meanwhile, STC chief and PLC member Aiderous al-Zubaidi has spent considerable time in the UAE and Riyadh, attempting to secure fuel to ease Aden’s electricity crisis. But power cuts and protests continue to erode the STC’s credibility, given that the group controls the interim capital. At the Al-Qarrah festival in Yafea in June, local tribal leaders conspicuously shut out STC propaganda, signaling mounting resentment of Al-Zubaidi’s Al-Dhalea-dominated leadership. Southern activist Anis Saad al-Jardami’s death in an STC detention center after reportedly being detained for insulting Al-Zubaidi has inflamed tensions further, with the victim’s family demanding an investigation and refusing to claim the body absent accountability.

On June 1, Bin Breik returned to Aden for the first time since his appointment and unveiled a 100-day plan to revive the economy and stabilize the collapsing rial. However, without the Saudi funds he had tried to secure before arriving in Aden, his plan is unlikely to gain traction. As political horse-trading drags on over cabinet slots, public frustration grows.

While the names and faces at the top may have changed, the government remains starved of cash, crippled by factional rivalries, and heavily dependent on foreign sponsors with conflicting interests. Given these challenges, substantive shifts to improve governance and service delivery appear unlikely.

Women’s Protests Challenge Authorities in Aden

In early May, a wave of women-led protests erupted in Aden, highlighting deep frustration over failing public services. Dubbed the “Women’s Revolution,” the protests began in Khormaksar district and quickly spread across the city and beyond, driven by demands for electricity, water, salaries, and respect for basic rights.

The first demonstration took place on May 6 in Khormaksar’s Al-Aroud Square, organized by civil society groups and women-led networks. Slogans like “We want electricity,” “Freedom and human dignity,” and “No to the STC, no to the government” reflected anger at both the local administration and the broader anti-Houthi coalition. Crucially, protesters avoided partisan or secessionist slogans, which prevented the STC from co-opting the movement for its own political aims. STC supporters reportedly arrived waving Southern flags but were asked to put them away. Despite warnings from STC security officers and online campaigns aimed at discouraging participation, the protests gained momentum in the following weeks.

A second, larger demonstration followed on May 10 in the square, echoing the same demands. Chants of “Electricity, water, and salaries are rights, not requests” and “Where are you, men of Aden?” underlined the frustration over years of unreliable services and unpaid wages. Videos and images of the protests quickly spread on social media, amplifying calls for action.

Recently appointed Prime Minister Salem Bin Breik publicly praised the courage of the protesters and promised solutions. But at the local level, the response was more repressive. On May 12, Aden’s Security Department attempted to ban any protests or gatherings without prior authorization in an effort to quell the growing movement. In an attempt to head off further protests, STC-affiliated authorities doubled down on restrictions. When hundreds of women and young people gathered again in Khormaksar’s Al-Aroud Square on May 17 and attempted to march through the streets, STC forces fired warning shots into the air to disperse them. Later that night, anger spilled into other areas. In Khormaksar’s Al-Salam neighborhood, protesters blocked roads and burned tires to draw attention to frequent power outages. Meanwhile, the STC issued a statement supporting the right to peaceful protest but warned against using demonstrations to undermine the secessionist cause.

The protests were not limited to Khormaksar. On May 15, a major rally in Aden’s Al-Mansoura district demanded the release of detainees and the forcibly disappeared, focusing in particular on human rights activist Wassim Aqrabi, arrested nearly two weeks earlier without charge. Protesters carried his photos and banners demanding accountability, calling for an end to enforced disappearances and arbitrary detention.

The momentum extended into Abyan governorate, where women protested over the course of several weeks. On May 17, in the governorate’s capital, Zinjibar, protesters called out the marginalization of women, demanded access to jobs and political participation, and insisted on a safe environment to exercise their rights—linking the Aden demonstrations to a broader push for action to improve the political, economic, and security situation in government-held areas.

On May 24, STC-affiliated security forces stormed a women’s sit-in at Al-Aroud Square and forcibly dispersed demonstrators who had camped out since May 11. Islah-affiliated Nobel laureate Tawakkol Karman condemned the STC’s crackdown, warning it would provoke more “revolutionary escalation,” but protesters rejected her intervention, saying she was not involved in the protests and did not speak for the women on the ground. Similar protests in Taiz on the same day jolted the Islah party. The following day, the women’s group Majidat Nisa’a Aden (“Glorious Women of Aden”) issued a defiant statement condemning deteriorating living conditions and declaring that their “patience has run out,” vowing to sustain protests until their demands were met. On May 26, Security Belt forces Chief of Staff Jalal al-Rubaie convened a high-level meeting to address mounting tensions and growing public anger over the heavy-handed crackdown.

On June 12, a fresh round of women-led demonstrations erupted in Al-Mualla district, showing that the movement had not been silenced. This time, several women, including prominent lawyer and human rights advocate Afraa Hariri, were arrested by STC-affiliated forces but later released under public pressure. On June 28, local media reported that STC-affiliated security forces forcibly dispersed a women-led protest demanding improved public services and living conditions in front of Al-Maashiq Palace in Aden’s Crater district and arrested two female activists, Amna al-Maysari and Khadiga al-Sayed.

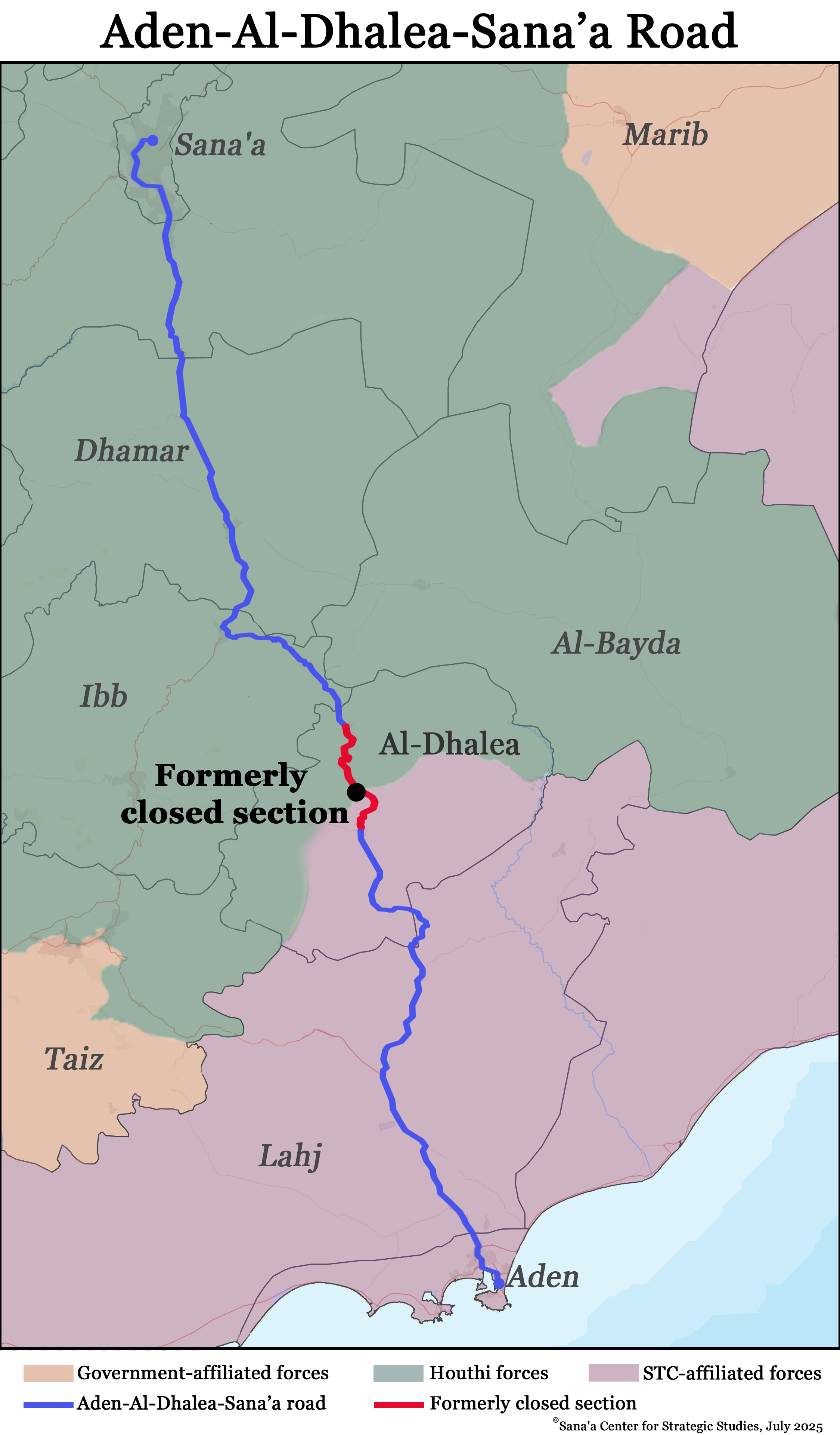

Sana’a-Aden Road Reopens in Al-Dhalea

On May 18, government-appointed Al-Dhalea Governor Ali Muqbil Saleh announced plans to reopen the main road linking Sana’a and Aden via Al-Dhalea, which had been closed since 2018. The announcement came after the closure of the main Sana’a-Aden route through northeastern Lahj and was presented as a measure to ease the humanitarian situation in Al-Dhalea, according to local authority sources. Israeli airstrikes that damaged Hudaydah’s ports and put Sana’a airport out of commission may have added to concerns about humanitarian aid delivery. Restoring road access was a key part of the April 2022 UN-backed truce.

In the last week of May, the road reopened after delays caused by efforts to clear mines and unexploded ordnance, repair damage from previous clearance efforts, and disagreements among the parties, who accused each other of refusing to open their side first. The STC quickly expanded its presence, taking over checkpoints in the Murais area of Al-Dhalea’s northern Qaataba district. Military leaders and armed groups in many areas around the country rely on fees collected at checkpoints to fund operations and maintain influence.

On June 5, the Houthi-affiliated Customs Authority set up a temporary customs outlet in the Irfan area of Damt district, northwestern Al-Dhalea, to regulate imports along the reopened road. Local activists claim that the Houthis intend to impose new customs fees on all goods, commodities, and vehicles entering their territory and will not accept customs documents issued by the government in Aden. Similar steps have been taken in Al-Bayda and Taiz. In the weeks since the road’s opening in late May, Houthi authorities have come under criticism for charging high tolls and fees. The US Embassy in Yemen called out the group for what it said were “Houthi restrictions on goods, bribes at checkpoints, and supply blocks.”

Growing Separatist Wave in Hadramawt

Hadramawt continues to witness a historic political shift, in which groups led by tribal leader and Deputy Governor Amr bin Habrish push for self-rule and attempt to undermine the authority of Governor Mabkhout bin Madi in Mukalla. Amid this upheaval, a new political group was announced in Seyoun city on April 14 – the Change and Liberation Movement. Although the group is relatively minor compared to factions led by Bin Habrish, Bin Madi, and the STC, its rise highlights the shifting political winds in the governorate. The Change and Liberation Movement is led by Abu Omar al-Nahdi, reported to be a former Al-Qaeda associate of Syria’s new leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, with whom he fought in Iraq. Al-Nahdi, from the Banu Nahd tribe, reportedly left Yemen’s Al-Qaeda branch in 2018. STC-aligned commentators have noted the movement’s name alludes to the “change” slogan of Yemen’s 2011 uprising and the “liberation” of Al-Sharaa’s Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (Syria Liberation Group), which seized power in Syria in December. The Syrian example has motivated some pro-government forces to call for a new military campaign against the Houthis.

The Change and Liberation Movement is tapping into momentum built by the Hadramawt Tribal Alliance (HTA) and the Hadramawt Inclusive Conference (HIC), which have grown stronger under the leadership of Bin Habrish since 2022 in response to the weakness of the PLC and the Aden-based government, and the STC’s attempts to assert control in Hadramawt. The movement’s new X account posted a video of its launch, calling it “a trend born of popular anger, to raise the banner of dignity and break the chains of hegemony,” with visible support from Kinda tribesmen. In his speech, Al-Nahdi said, “Revival begins with including the people in decision-making, choosing capable people, implementing transparency, and strengthening the judiciary, media, education, and security.”

The new movement potentially poses another challenge for the STC, following President Aiderous al-Zubaidi’s unsuccessful attempt in March to win over the HTA and HIC along with their leader, Bin Habrish. STC sources claim Al-Zubaidi’s criticism of Bin Habrish during his March 16 meeting with Hadramawt Governor Mabkhout bin Madi—alleging Houthi ties—pushed the HTA and HIC to turn to Saudi Arabia. Bin Habrish traveled to Riyadh, where Saudi Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman reportedly pledged support and indicated willingness to set aside the Hadramawt National Council, whose creation Saudi Arabia backed in 2023.

The STC’s position was also weakened when two of its most senior members, Faraj al-Bahsani and Ahmed bin Breik, made statements appearing more aligned with Hadrami unity than STC policy. On April 12, Al-Bahsani, a member of the PLC and former governor of Hadramawt, called for consolidating Hadrami interests under a single political banner. The same day, Bin Breik, a vice president in the STC, backed Al-Bahsani’s appeal. Tensions rose after Al-Zubaidi’s failed outreach, and Bin Habrish accused the governorate’s Security Committee of blocking efforts to push for self-rule. On April 18, Bin Breik returned to Mukalla from medical treatment in the UAE. In the governorate capital, he emphasized that Hadramis should manage their own affairs free from outside interference. He met with Bin Madi, and consulted with 2nd Military Region Commander Major General Talib Bargash and Hadramawt Coast Security Chief Matia al-Menhali, stressing the need to unify the Hadrami Elite and other STC-linked forces against Saudi-backed rivals, including the Islah-affiliated 1st Military Region and the new Hadramawt Protection forces tied to Bin Habrish. On April 21, Bin Breik said Hadramis should resolve their issues free from foreign influence, pointedly leaving out any mention of the UAE, the STC’s primary backer.

The events in Hadramawt have added to Saudi and US concerns about the unity of Yemen’s anti-Houthi bloc. On April 20, US Ambassador to Yemen Steven Fagin spoke with Bin Madi, underscoring US concern that tensions in Hadramawt could weaken the anti-Houthi coalition. In a statement, the US embassy called for unity and peaceful dialogue to maintain security and focus on the Houthi threat.

On April 24, the STC held a large rally in Mukalla under the slogan “Hadramawt First.” The group directed its media to boost coverage, hoping to capitalize on the popular slogan adopted by the HIC. The day marked the ninth anniversary of Mukalla’s liberation from Al-Qaeda—an event the STC used this year to show its strength vis-a-vis Bin Habrish. A day prior, Bin Breik led a celebration, holding meetings with tribal leaders. His messages appeared aimed at countering the HTA’s push for self-rule and other Hadrami rivals. In a televised speech, Bin Breik branded Abu Omar al-Nahdi as “one of the most prominent terrorist elements on the Hadramawt coast,” highlighting Al-Nahdi’s alleged Al-Qaeda ties. Meanwhile, the HTA held its own commemoration in Ghayl Bin Yamin district.

During Bin Breik’s public appearances in Mukalla, STC forces were deployed to checkpoints near Seyoun, including the Jathma military camp, with around two dozen UAE-supplied armored vehicles. One goal may be to sway Saleh al-Juaimilani, the commander of the 1st Military Region, toward the STC as Bin Habrish moves closer to Riyadh. Bin Habrish’s ties with Saudi Arabia may have factored into the March arrest of Mohammed Omar al-Yamini, Chief of Staff of the 2nd Military Region. Al-Yamini was detained over “specific security issues,” while pro-STC outlets accused him of weapons smuggling from Al-Mahra. His tribe accused Governor Bin Madi and forces in Mukalla of politicizing the case. Authorities said Al-Yamini’s phone contained messages with Houthi contacts in Sana’a. After disputes over jurisdiction, he was sent to Riyadh for questioning by Saudi and Yemeni officials.

Bin Breik appears to be consolidating his own standing as a potential Hadramawt leader. Meanwhile, Ali Nasir Mohammed, a former president and prime minister of South Yemen, has reemerged, giving interviews and calling for a new national dialogue. Houthi media have favorably covered his statements in the past, and he is known to receive visits from Omani officials at his Cairo residence.

On May 8, PLC head Rashad al-Alimi authorized PLC member and former Hadramawt governor Faraj al-Bahsani to establish a fund to channel local oil and diesel revenue into the electricity sector. The Hadramawt Development Fund will supervise the delivery of fuel from the PetroMasila oil fields, which local tribes have blocked from being transferred to Aden since March.

Other Developments

April 25: The Foreign Ministry announced the reopening of Yemen’s embassy in Damascus, which the Houthis had controlled from 2016 to 2023.

May 3: The STC opened a representative office in Washington, D.C., calling it its “first mission” to the US. The US Department of Justice reported in a public filing that the STC hired PR firm Independent Diplomat for over US$1 million to promote its image.

May 24: Journalist Mohammed al-Miyahi was sentenced to 18 months in prison for comments critical of the Houthis. He was also ordered to pay a YR5 million fine and pledge not to repeat the offense. Al-Miyahi had been detained since September 2024. Activists condemned the sentencing as part of a broader crackdown on free speech.

May 25: A Houthi court sentenced Adnan al-Harazi, owner of Prodigy Systems and Medex Connect, to 15 years and confiscated his assets. He was first arrested in January 2023 for alleged espionage. Prodigy monitored aid for international organizations, while Medex Connect handled medical reports. In 2024, he was sentenced to death and later appealed, leading to nearly 30 legal sessions and protests over the detention of his family members.

May 27: PLC head Rashad al-Alimi visited Russia at President Putin’s invitation to discuss bilateral ties, the Yemen conflict, and regional security.

May 29: US Ambassador to Yemen Steven Fagin was temporarily reassigned as Chargé d’Affaires in Baghdad, where he served as Deputy Chief of Mission from 2020-21. He remains accredited to Yemen.

June 4: Heads of UN agencies and major international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) renewed calls for the release of aid workers detained in mass arrests by the Houthis a year earlier. They said 23 UN and five INGO staff remain in Houthi custody.

June 5: President Donald Trump announced a travel ban on nationals of 12 countries, including Yemen, effective June 9. In 2017, he imposed a similar ban on seven Muslim-majority countries, including Yemen.

June 13: Hundreds gathered in Sana’a to mark Eid al-Ghadir (Waliyat Day), commemorating the Prophet Mohammed’s supposed appointment of his nephew, Ali ibn Abi Talib, as successor as caliph. The Houthis use the holiday to help bolster their claim to rule as descendants of the Prophet.

June 25: The Houthi-appointed Social Affairs Minister, Samir Bajaala, met with community leaders from the Horn of Africa to discuss migrant work, protection, and residency.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية