Houthis Draw Blood in First Commercial Shipping Casualties

Houthi attacks on commercial shipping have continued unabated since the beginning of the year, undeterred by a series of countermeasures from the United States and its allies, including retaliatory strikes, a terrorist designation and associated financial sanctions, and the formation of multiple anti-Houthi naval operations.

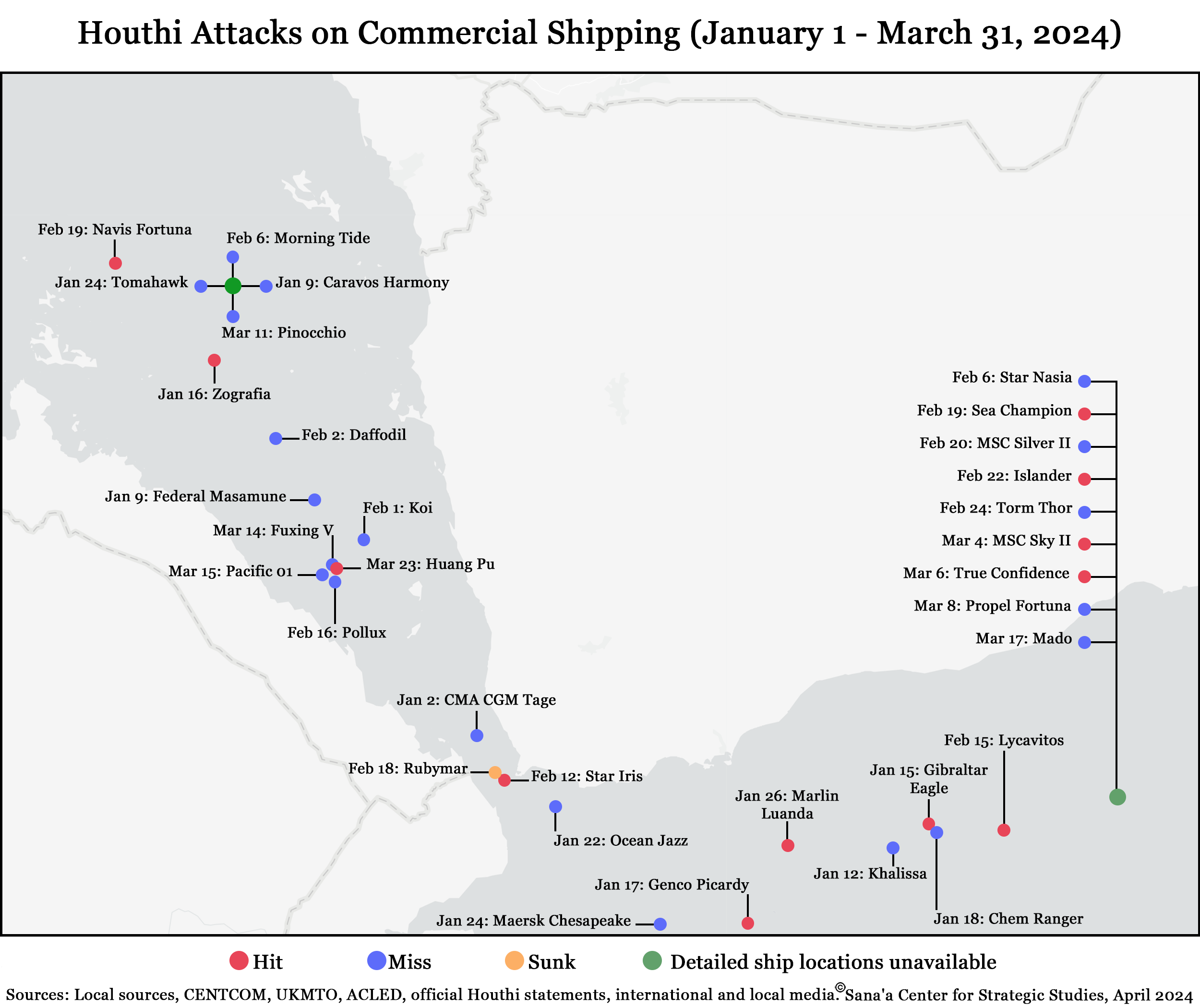

Since January 1, the Houthis have targeted 34 commercial vessels, 13 of which they have successfully hit. Of the targeted ships, at least 13 had clear ownership links to the US or United Kingdom, and an additional eight had ties to companies affiliated with US-, UK-, or Israeli-based entities. Other sources have claimed attacks on an additional four ships, but the Sana’a Center was unable to independently confirm this information.[1]

The majority of ships were traveling to destinations other than Israel, and all were targeted in either the Red Sea or the Gulf of Aden. Houthi forces have employed a number of weapons to target ships, including a variety of missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), unmanned surface vehicles (USVs), and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs).

Tensions spiked in the Red Sea on February 18 after the Houthis struck the Rubymar, a Lebanese-operated vessel transporting over 21,000 metric tons of fertilizer. The crew was forced to abandon ship and the vessel ultimately sank – a major purported victory for the Houthis. However, any initial feelings of triumph were likely cut short the following day, after a reported logistical mishap led to Houthi forces accidentally targeting a ship carrying foodstuffs to Yemen – including the Houthi-controlled port of Hudaydah.

Other hits – two of which sparked major fires that prompted interventions by the Indian navy – were eclipsed by the first civilian casualties from Houthi attacks on March 6. The Houthi attack on the True Confidence, a Liberian-owned vessel which had been previously managed by an American corporation, left one Vietnamese and two Filipino sailors dead and four others seriously injured.

In the midst of this prolonged naval struggle, the hijacked Galaxy Leader and its 25-member crew remain stranded in a secluded bay to the north of Hudaydah city, nearly five months since Houthi forces captured the vessel in November. But while satellite imagery shows that Houthi forces have moved the vessel within only a hundred meters or so of the coastline, the group has not yet made any public indications that it intends to comply with renewed American calls for the ship and crew’s release. In fact, a Houthi spokesman told CNN that the decision to release the crew was now “in the hands of Hamas,” raising concern over whether they will be allowed to return home any time soon.

American and British Airstrikes Target Houthi Territory

On land, retaliatory strikes meant to deter attacks on shipping have morphed into a drawn-out tit-for-tat campaign, in which US and UK militaries are engaging the Houthis in a sort of morbid real-life iteration of Hasbro’s Battleship.

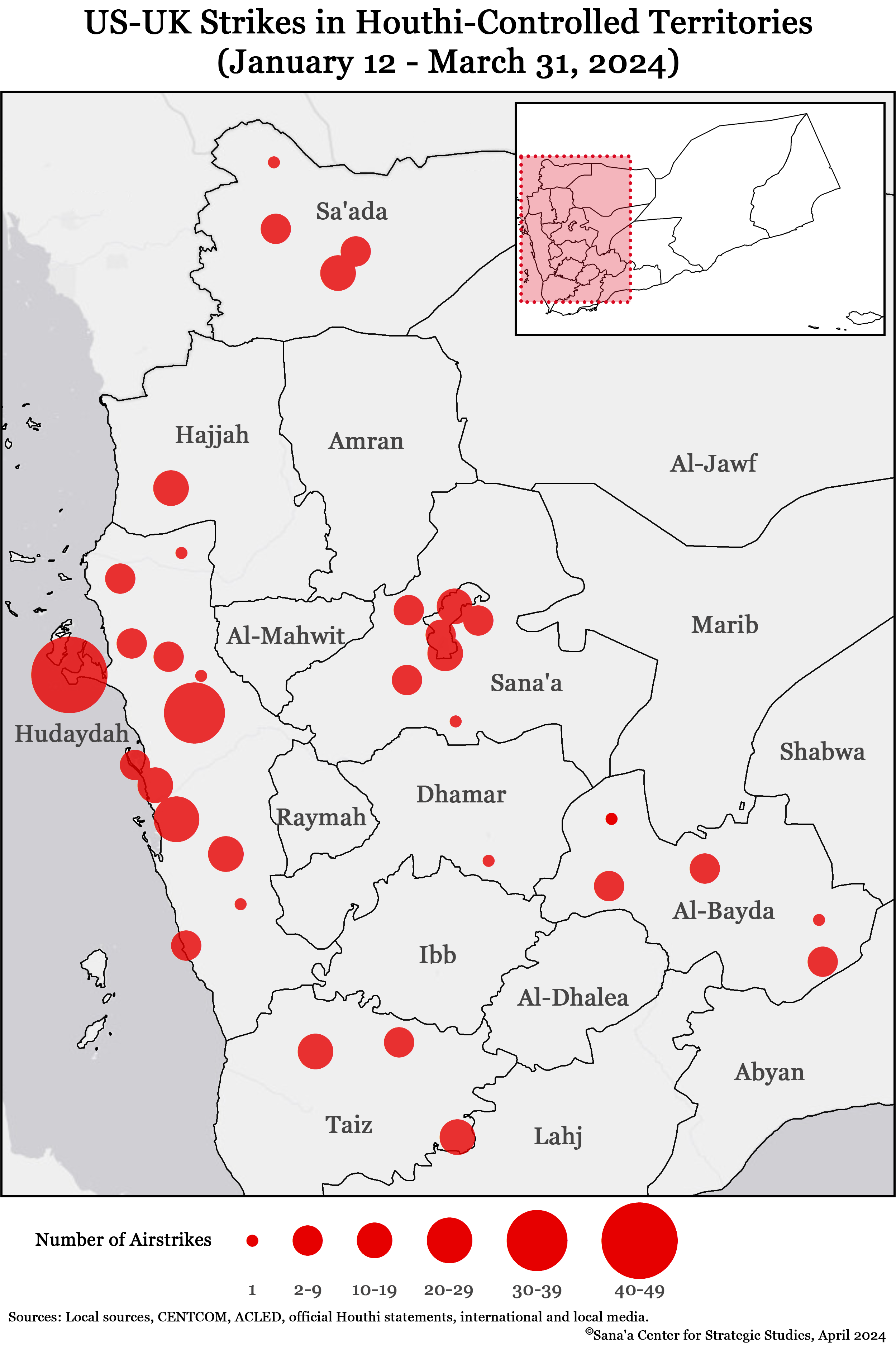

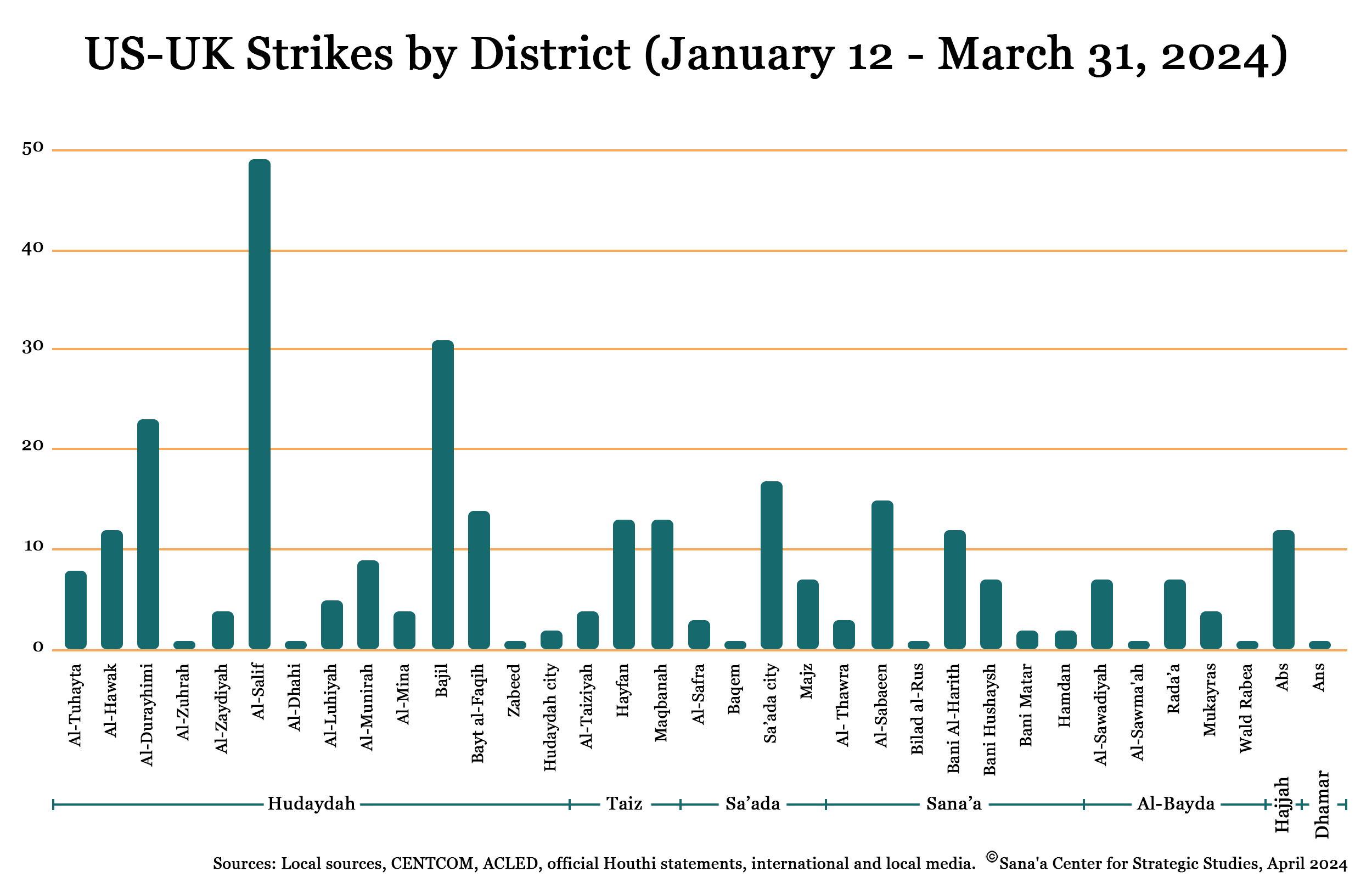

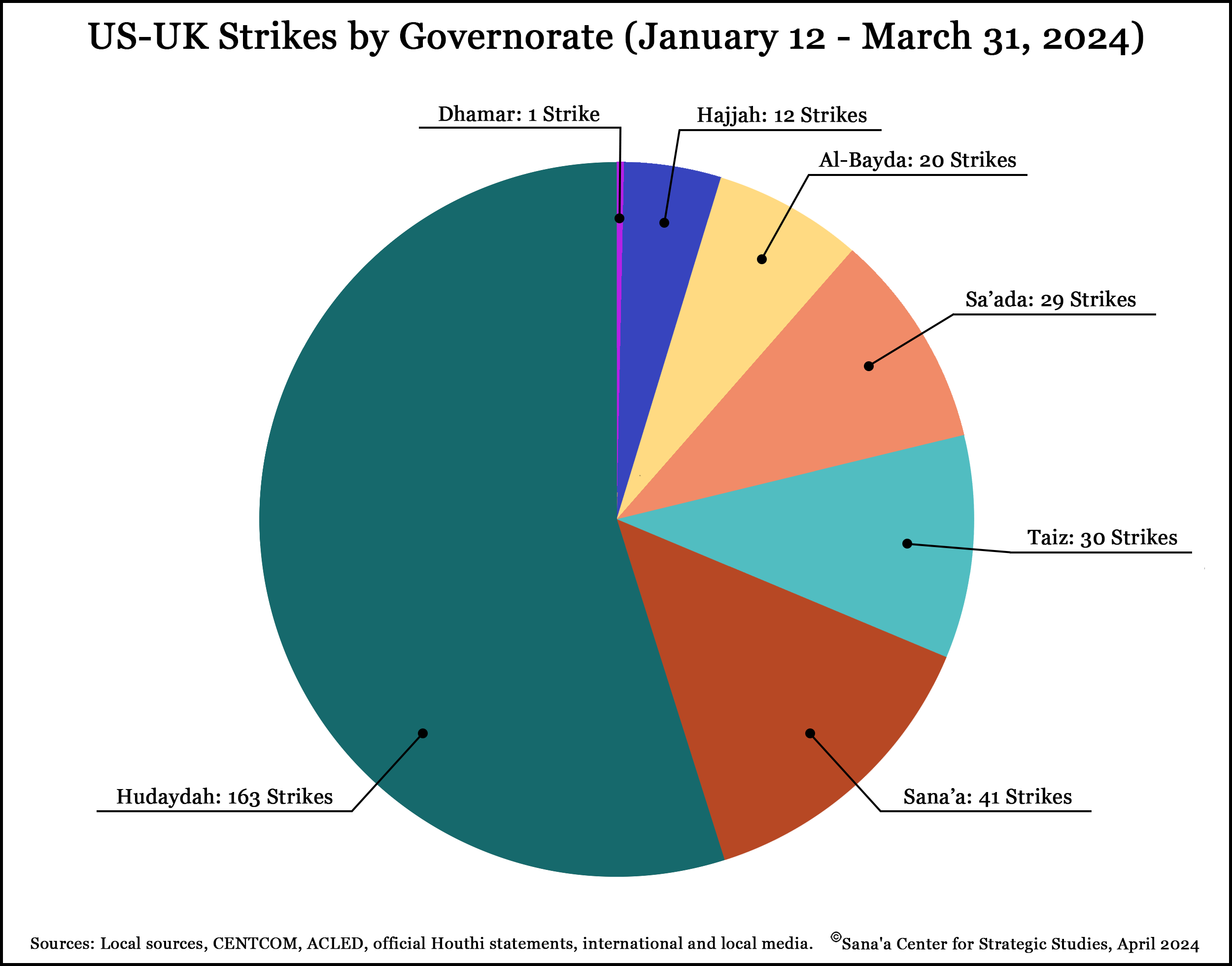

The Sana’a Center has recorded an estimated 296 American and British air strikes on Houthi territory.[2] The initial attack on January 12 consisted of at least 25 strikes in 18 locations, though some sources have reported as many as 60. Of these, American aircraft and warships are responsible for the vast majority, with British forces publicly participating in just four strikes. While reports of the casualties incurred are sparse and unreliable, the Sana’a Center has received reports of at least two civilians killed and nine others wounded, with the actual numbers likely much higher. The number of Houthi casualties also remains murky, but medical sources in Hudaydah say that by mid-February, airstrikes had killed at least 31 Houthi soldiers and wounded nearly 100 others – with four Iranian officers from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps reportedly among the dead. The Houthis, meanwhile, have reported that a total of 424 airstrikes have killed 37 people and wounded an additional 30 as of April 4.

In terms of weakening the Houthis’ ability to threaten shipping lanes, it is difficult to gauge how significantly US/UK operations have affected Houthi firepower without reliable statistics on the full range of the group’s arsenal. The most impactful strikes – at least to Houthi top brass – likely include those of February 24, which targeted weapons depots and bunkers in areas surrounding Sana’a city that Houthi top leadership are known to frequent. According to Houthi military sources, strikes like these have led to heightened security measures (and perhaps a healthy dose of paranoia) for military commanders, who have been said to restrict the use of digital phones and other technology that can be tracked. Other attacks have focused on coastal areas to the north of Hudaydah city – including Ras Issa, Al-Jabanah, Salif, and Al-Katheeb. These areas have taken the brunt of the bombing, but airstrikes have also targeted known depots and military sites across Houthi-held territories in Sa’ada, Sana’a, Al-Bayda, Dhamar, Taiz, and Hajjah. Nonetheless, the fact that much of the Houthis’ missile and drone arsenal consists of platforms that can be easily moved or relocated affords the group’s missile strategy a guerilla-esque element that makes traditional targeting more difficult.

Satellite imagery shows that many of these sites – particularly in Ras Issa – have sustained heavy damage. Washington is likely to point to images like these as evidence that Operation Poseidon Archer is, at least on some level, eroding Houthi capabilities. Nonetheless, with an asymmetric battlefield favoring the Houthis and the actual number of the group’s weapons stockpiles unknown, it will only become more difficult to justify further attacks to Congress and American taxpayers. After all, it only takes one Houthi drone launched toward the sea for the group to remain a threat in the eyes of international shippers and a hero in the eyes of its base.

With this in mind, threats of escalation from Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi and unconfirmed reports of US Defense Department officials eyeing Socotra as a strategic military location fuel fears that a more formal US presence in Yemen may be on the horizon.

Foreign Firepower in Yemen’s Waterways

Anti-Houthi Operations

As attacks on shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden have increased, so too have efforts to both combat and mitigate Houthi maritime aggression. The US-led Operation Prosperity Guardian, which Washington officially launched on December 18 with the support of over 20 countries, has continued in full force. The American Navy and its partners have downed hundreds of Houthi drones and missiles – including 28 in a single day, and 21 in another instance – but at the cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars in military equipment, the deaths of three American seamen in two separate instances, and one very close call.

In tandem, the European Union launched Operation Aspides on February 19. The mission, which is based in Greece and led by an Italian admiral, had the initial public participation of seven member states, four of which have lent ships to the cause so far. Estonia later pledged a single service member, along with the Dutch, who sent a frigate in late March to assist both the American and European missions. Aspides’ commencement has made shipping lanes quite crowded in terms of foreign military power, but – aside from a jumpy trigger finger on the Germans’ first day – European warships seem to be working closely in league with their American counterparts. Aspides has allowed cautious EU governments to justify a military presence in the Red Sea, with a looser mandate that could prevent them from getting embroiled should the Americans choose to escalate what is already one of their most intense naval operations since World War II.

The Indian navy, while not formally involved in either of the maritime coalitions, has also played a large role in protecting waterways around the Gulf of Aden, rescuing two ships after they caught fire, while also pursuing and extraditing Somali pirates.

Questions Surround Houthi Intelligence Sources

However, it appears collaboration is not limited to anti-Houthi coalitions – the Houthis’ proven ability to target and track commercial vessels with relative accuracy has raised questions about Iran’s role in the attacks. To the Houthis’ credit, at least some of the group’s success in targeting ships can be attributed to their installation of GPS tracking towers along the coast of Hudaydah and launching of systematic patrols carrying tracking systems throughout the Red Sea, according to Houthi military sources and local fishermen.

However, American officials have expressed specific concern over the presence of the Behshad, an Iranian cargo ship long suspected of being one of Tehran’s reconfigured spy vessels, in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. These suspicions were confirmed in part at least last month after the Iranian government warned Americans against tampering with the Behshad and another vessel, which it dubbed “floating armories.”

The remark followed reports that US forces had conducted a cyber attack on the Behshad in early February, explaining the cargo ship’s unexpected detour from its typical meandering route through the Red Sea to dock in Djibouti, only a short distance from a major Chinese military base. In the first days of the Behshad’s more than two-week stint along the coast of Djibouti, Houthi attacks on commercial vessels witnessed a six-day hiatus, one of the longest lulls since attacks picked up intensity in the new year.

By early March tensions seemed to have abated enough for the Behshad to resume its sweep of the Gulf of Aden, with tracking systems putting the ship less than 50 nautical miles from the True Confidence when the Houthis launched their most precise and deadly strike to date. Interestingly, investigations following the attack on the True Confidence revealed that the ship was recently owned by Oaktree Ltd. – the same American company that is related, via a Greek affiliate, to an Iranian oil tanker that was seized by US forces last year, and then recaptured by Iranian forces this January.

The True Confidence’s ownership has raised questions not only about ship nationality in general, but also over the Houthis’ targeting methodology. At least six of the targeted vessels have changed ownership from an American, British, or Israeli-affiliated company, several of which did so after the start of the Red Sea shipping crisis. Initial reports from shipping experts insinuated that the Houthis could be using an outdated shipping database, but the targeting could be intentional, in an effort to circumvent the possibility of companies switching ownership to avoid targeting. And while a recent attack on a Chinese-owned ship raised further suspicions that the Houthis may be targeting ships with ghost owners, the reality is likely a mix of intent and negligence.

Houthi Repression Continues at Home Despite Calls for Liberation Abroad

Continued rhetoric from Houthi leaders demanding the liberation of Palestine appears to be successful in bolstering support for the Houthis’ domestic base, as evidenced by massive demonstrations in Houthi-held territories on an almost weekly basis. However, calls for goodwill abroad have apparently not stopped the group from acting with impunity in Yemen.

In mid-March, Houthi forces in Al-Bayda’s capital Rada’a city made international headlines after a local supervisor ordered the demolition of a house in the Al-Hafrah neighborhood, which in turn caused the collapse of three neighboring homes while the inhabitants were still inside. Estimates put the number of casualties upward of 12, with nine of the victims belonging to a single family.

The incident garnered censure not only from typical anti-Houthi voices, but also prompted rare internal criticism from top Houthi figures, who have demanded an investigation and reparations. But while the Al-Hafrah demolition is a tragic and extreme iteration of violence against civilians, it is by no means the first time the tactic has been employed by Houthi forces. Since the beginning of the year, the Sana’a Center has documented five incidents of Houthi forces besieging residential homes: on February 6 and 12, twice on February 13, and on March 7. On February 6, the Houthis blew up the family home of the Al-Taweel family in the Al-Mashaaebah area of Al-Mashanah district in southwest Ibb, resulting in violent clashes in the following days.

Human rights groups and activists have also highlighted a steady number of violations in Houthi prisons since the beginning of the year. In late January, a man died from suspected torture complications two days after his release from a Houthi prison in Sana’a, after being kidnapped from his home several weeks earlier. On February 8, a detainee in a Houthi detention center in Sana’a was denied medical care after sustaining injuries, reportedly from torture. A week later, the imprisoned head of the Yemeni Teachers Club, who was arrested by Houthi forces in October 2023, was also reportedly denied medical assistance after he suffered a hunger-strike-induced coma. And on February 26, another man reportedly died from torture in a Houthi prison in Taiz.

Maritime Fighting Increases Domestic Tensions and Frontline Fighting

Houthi attacks on commercial vessels and retaliatory airstrikes have also contributed to a heightened sense of tension in regard to internal security and frontline fighting. Houthi forces have cracked down in areas near mobile launch sites, blocking off large swaths of residential areas in southern and coastal Hudaydah and arresting four civilians for photographing a military site in Ibb on January 31.

In turn, local residents, fearing their lands could be targeted by American and British airstrikes, have pushed back against Houthi militarization in urban areas, with local authorities in Hudaydah accusing the group of using civilians as “human shields.” And despite the fact that the group’s recruitment (of both adults and children alike) indicates continued support across its base, opposition has, at times, turned violent. Tribesmen from Al-Bayda’s western Al-Riyashiyah district opened fire on a Houthi missile launcher near their homes in early February, leading to clashes that ended with the arrest of 10 tribesmen and the death of several Houthi fighters, according to tribal sources.

In non-residential areas, Houthi forces have heavily reinforced frontlines in coastal Hudaydah, particularly in the Bayt al-Hashash Rub’a al-Mahal areas of Hudaydah’s southern Hays district. Houthi positions in Al-Dhalea also received heavy reinforcements in late March following several weeks of intense fighting, with additional troops being sent from Sa’ada, Dhamar, and Ibb governorates to frontlines in the Hajar, Al-Fakher, Bab Ghalaq, and Murais areas. Local residents in both governorates worry that the reinforcements could be used as justification for a regional offensive, even if attacks at sea abate in the near future.

Fighting between Houthi, pro-government, and STC-affiliated forces has continued at a steady pace across multiple districts, indicating that the Houthis are not sacrificing internal strategic maneuvers for their maritime attacks. Clashes in Al-Dhalea were particularly fierce in recent months, with a two-week period from March 15-29 leaving an estimated 72 Houthi fighters dead and at least 125 wounded, and 28 anti-Houthi soldiers dead and 69 others wounded. Aqbat Tharah and Aqbat al-Halhal, along the border of Al-Bayda’s southern Mukayras district and Abyan’s northern Lawdar district, also continue to be a hotspot for fighting, along with fronts to the south of Marib city, particularly in Harib district and the eastern Al-Balaq Mountains.

Efforts to re-open roads through several of these areas – particularly Aqbat Tharah – raise questions not only about the future of these battlefronts, but also the politicization of such desesclation measures as Houthi and government officials drift further away from hopes at the end of 2023 that a UN-brokered cease could be on the horizon.

Extremist Extermination? Several Al-Qaeda Leaders Reported Dead

A mysterious chain of deaths haunted Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)’s Yemen branch this month following the unexpected announcement of the death of the group’s Saudi-born leader, Khaled Batarfi, on March 10. Batarfi, who reportedly died after several months of illness, took over the Yemeni branch of Al-Qaeda in February 2020. He was replaced by Saad al-Awlaqi, a senior Yemeni figure with strong tribal ties in Shabwa who is popular among younger members of the group.

Following Al-Awlaqi’s appointment, a series of freak accidents involving other senior AQAP members in Yemen have raised concerns that the group’s new chief may be trying to wipe the slate clean of potential rivals– leaving room for a handpicked leadership of his choice. Among the deceased are Khaled al-Sana’ani, who was responsible for Al-Qaeda’s recent success in drone warfare and was reportedly killed in a traffic accident on March 15. The following day, a fire reportedly broke out at the home of and led to the death of Ibn al-Madani, the son of Saif al-Adl, the senior Egyptian jihadist and global Al-Qaeda leader based in Iran. Two weeks later, a third figure – Abdullah Manea Hadban, also known as Abu Arfaj al-Jawfi – was allegedly swept away by a flood in the Sirr Valley in Hadramawt’s Al-Qatn district.

- Editor’s note on attacks on commercial shipping methodology: Data detailing Houthi attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden is gathered from a variety of sources, including but not limited to: local sources, the United States Central Command (CENTCOM), reports from maritime surveyors such as United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO), the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), official Houthi statements, and international and local media outlets. Claimed strikes that could not be independently verified by the Sana’a Center were not included in this report.

- Editor’s note on airstrike methodology: Whenever possible, the Sana’a Center relies primarily on reports from local sources in Yemen. When this information is not available, data is supplemented from a variety of open-source materials. In instances where these third-party sources reported that an attack occurred, but did not specify the number of strikes, the Sana’a Center tallied it as one strike. This discrepancy, combined with a lack of clear reporting from involved parties, may contribute to variation between data reported here and in other reports.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية