Food Security Expected to Worsen

In its Yemen Food Security Update, the World Food Programme (WFP) indicated that the country’s food security situation continues to deteriorate, with 62 percent of surveyed households not having adequate access to food in August, despite an 8 percent month-on-month improvement. Sixty-four percent of affected households were located in areas under the control of the internationally recognized government, and 62 percent in areas under Houthi control. Short-term relative improvement in food consumption was observed in all governorates, particularly in Dhamar, Sa’ada, Sana’a, and Marib. However, severe food deprivation continued to affect 34 percent of households nationwide. Twelve percent of households in government-controlled areas and 18 percent of households in areas under Houthi control had at least one member who went 24 hours without food.

In government-controlled areas, the improvement was primarily attributed to the dramatic appreciation of the rial, which lowered the prices of imported food. The currency’s recovery has brought down the price of a Minimum Food Basket (MFB) by 34 percent month-on-month and 12 percent year-on-year. Prices of essential food items such as wheat flour, red beans, and sugar followed a similar pattern. The pump price of petrol and diesel dropped between 24 and 28 percent, respectively, reducing the cost of bringing food to market.

In Houthi-controlled areas, the change was driven by the partial payment of salaries for public sector employees and improved labor opportunities linked to increased qat production following July and August rainfall. The rainy season also supported the regeneration of pastures for livestock. Due to the Houthis’ enforced exchange rate scheme, official petrol and diesel prices moved little, and the cost of an MFB has remained almost unchanged year-on-year.

Through August, food imports declined 20 percent at Houthi-controlled Red Sea ports compared to the same period last year, and fuel imports were down by 27 percent. The decline was attributed to decreased capacity, disrupted operations, and extensive damage caused by US and Israeli airstrikes. According to UNOCHA, over 80 percent of the country’s humanitarian aid, essential goods, and fuel, upon which 28 million Yemenis depend, flowed through Hudaydah as of July. In contrast, government-controlled ports witnessed a 45 percent increase in food imports, though fuel imports decreased by 17 percent.

Both areas benefited from the distribution of food aid. The World Food Programme (WFP) had completed four cycles of general food aid in government-controlled areas and two in Houthi-controlled areas, as of late August.

However, ongoing Houthi detentions of aid workers and members of civil society have forced many aid organizations to adapt their operations. The UN Resident Coordinator’s office has relocated to Aden, the WFP has paused its activities in the north, and NGOs are increasingly moving their operations to the south, fueling concerns over how aid will reach targeted populations in areas under Houthi control. The EU has stated that it will provide new support, which will prioritize “districts at highest risk of famine” in Yemen, but questions over accessibility and security remain. The humanitarian situation appears set to deteriorate further as conflict, economic instability, and severe reductions in aid funds are expected to leave an estimated 18.1 million people facing high levels of acute food insecurity between September 2025 and February 2026.

Government’s Fiscal Crisis Deepens

The internationally recognized government remains in the grips of a severe fiscal crisis, limiting its ability to meet critical spending obligations. Army units have gone unpaid since June, and civil servants have not received their salaries since July. The shortfall in liquidity is mainly attributable to the lack of sustainable revenues and institutional corruption, which undermines efforts at fiscal reform.

Since the end of 2022, the sharp decline in oil and customs revenues, once the backbone of the Yemeni economy, has left the state’s coffers severely depleted. The government’s budget deficit has grown in the absence of meaningful reforms to address fiscal leakage. Long-awaited Saudi financial support, amounting to 1.38 billion Saudi riyals (approximately US$368 million), was announced on September 20 but has not been provided as of the time of writing. The funding will be directed to support the government’s budget, purchase fuel supplies, and support the Prince Mohammed bin Salman Hospital in Aden. While the grant could alleviate some short-term financial pressures, its impact will be limited, as the funding will cover only a small portion of total government expenditures.

In an attempt to address its financial woes, the government began pushing for fiscal reforms. In late July, Prime Minister Salem bin Breik issued a decree to form a Supreme Committee for the State Budget for the fiscal year 2026. The formation of this committee was a positive step toward establishing a proper financial framework. The government has been operating without an official budget since 2019, a void that has complicated its operations, disrupted economic performance, and hampered its capacity to meet obligations and plan its finances. Saudi Arabia had linked any new financial support for the government to the creation of a clearer financial outlook, including the preparation of a transparent and implementable budget that reflects the government’s spending priorities.

Over the course of July and August, the Ministry of Finance and the government-affiliated Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) issued joint directives mandating that money exchange outlets close accounts held by government bodies within their respective accounting systems. The CBY-Aden issued a similar circular to banks. However, implementation has either been slow or not forthcoming. Dozens of government entities and institutions operate hundreds of illegal accounts in commercial banks and money exchange outlets, allocating state funds outside the public budget. Another deficiency is the lack of oversight of public salary payments. While the Ministry of Finance has made progress with disbursement, some military units have refused to share their payroll data, creating fertile ground for corruption.

The crisis has ignited a conflict between fiscal and monetary policies. In early September, the prime minister proposed three options to the central bank to address the fiscal deficit: overdrawing public accounts, utilizing banks’ foreign currency reserves, or printing more currency. CBY-Aden Governor Ahmed Ghaleb al-Maabqi rejected all three, arguing they would destabilize the rial, which has enjoyed a fragile recovery, and contravene the CBY-Aden’s adherence to a contractionary monetary policy. The CBY-Aden reported that the government’s direct borrowing from the central bank had reached YR6.9 trillion by the end of June, accounting for 92 percent of the total domestic public debt.

To raise funds from non-inflationary sources, the CBY-Aden introduced short- and long-term debt auctions. On September 10, it was supposed to sell one-year treasury bills and YR10 billion in three-year government bonds, with annual interest rates of 18 and 20 percent, respectively. While the outcomes of the auctions were not announced, the central bank’s success in mobilizing the required funds was likely limited. The viability of open market financing initiatives is uncertain given the precarious state of the financial system and the limited liquidity of commercial banks and other potential participants.

The government’s perilous fiscal position is not solely a result of internal failures. A Houthi blockade of hydrocarbon exports, formerly the primary source of government revenues, remains in place. The limited Saudi financial support has created a crippling fiscal gap. This support is being used for political leverage, compromising the Yemeni government’s sovereignty and forcing it to adopt economic and governance reforms, implementation of which is challenging given the fragmented state of its political, security, and financial institutions.

Rial Recovers After Government’s Short-Term Reforms

The new rial, which circulates in government-held areas, experienced significant fluctuation, hitting a record low in July before significantly rebounding and closing the period trading at YR1,632 per US$1. Before its resurgence, the rial had fallen as low as YR2,903 to the dollar. This dramatic rebound was driven by aggressive intervention from the CBY-Aden, along with considerable support from various factions within the government. Old rials remained stable in Houthi-controlled areas, trading at approximately YR535-536 per US$1 over the reporting period.

In mid-July, the new rial reached a record low of approximately YR2,903 per US$1 despite CBY-Aden’s foreign currency auctions, which have proved largely ineffective at stabilizing the currency. The central bank was pressured to postpone further actions in the light of dwindling FX reserves and delayed Saudi financial support. Furthermore, demand from commercial banks was consistently low: only 44 percent of the US$510 million offered across 15 auctions had been purchased by mid-July. Commercial importers had increasingly opted to secure hard currency on the open market, bypassing the CBY-Aden’s financing mechanism. Money exchangers acted as the primary drivers of the rial’s collapse, engaging in rampant currency speculation and manipulation by artificially inflating demand for hard currency within government-controlled areas.

Recognizing the systemic pressure on the rial, the CBY-Aden adopted a series of measures during July and August to tighten its control over the foreign currency market, suspending and revoking the licenses of numerous money exchange outlets and financial transfer networks accused of engaging in illicit currency speculation. This multidimensional strategy succeeded in temporarily rescuing the rial.

The CBY-Aden also pushed for the institutionalization of import financing, which culminated in the establishment of the National Committee for Regulating and Financing Imports in mid-July. Chaired by the Governor of the CBY-Aden, this committee has been granted broad authority to regulate foreign currency demand, control import financing, and curb speculation. By early August, the committee had approved its action plan and began receiving financing requests through banks and exchange companies for 25 essential commodities. The mechanism proved immediately successful, approving 91 import requests totaling US$39.6 million in its first week of operation. These tightened regulations yielded immediate results: the new rial appreciated by over 40 percent by early August.

The CBY-Aden’s success, however, was strongly opposed by the Houthi-affiliated Central Bank of Yemen in Sana’a (CBY-Sana’a), which, in mid-August, issued a ban prohibiting banks and exchange companies under Houthi control from engaging with the committee’s new import financing mechanism. This ban was intended to undermine the CBY-Aden’s capacity to leverage the financial sector’s hard currency reserves and maintain Houthi control over lucrative financial inflows.

In early August, the CBY-Aden further tightened its regulatory control over access to hard currency, reducing the ceiling on foreign currency sales for personal purposes from US$5,000 to just US$2,000, and requiring extensive documentation to prove the purpose of the transfer. The government also prohibited the use of foreign currency for all commercial and service transactions and financial contracts. The new regulations enforced the exclusive use of the Yemeni rial in all these transactions, entrenching it as the country’s primary unit of exchange.

Despite its appreciation, the rial remained vulnerable to manipulation. In late August, it experienced a brief and unexpected jump in value, seemingly driven by speculation and manipulation by money exchange outlets. It appreciated by over 23 percent, from YR1,630 to YR1,250 per US$1. The jump was short-lived, however, as the CBY-Aden intervened to push the exchange rate back towards its previous equilibrium of YR1,630 per US$1.

The rial remains stabilized near YR1,630, supported by the CBY-Aden’s sustained foreign exchange policy management and the late-September announcement of Saudi support. However, the value of the currency remains a critical concern, particularly if no further economic reforms are forthcoming. Long-term stability will require transforming recent interventions into sustainable policies and implementing structural reforms to access sustainable sources of foreign currency.

Food and Fuel Prices Fall with Rial Recovery

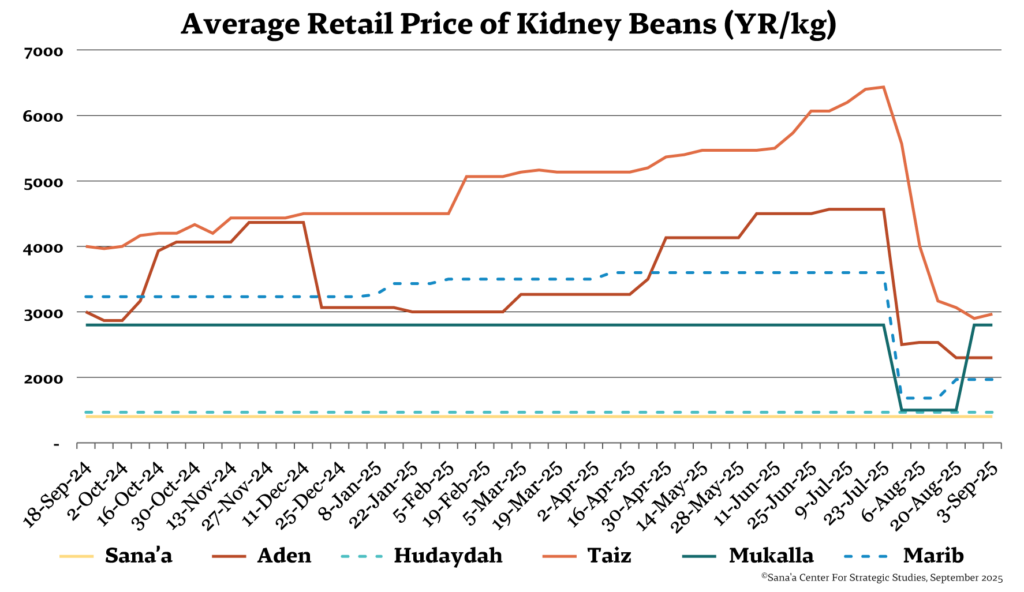

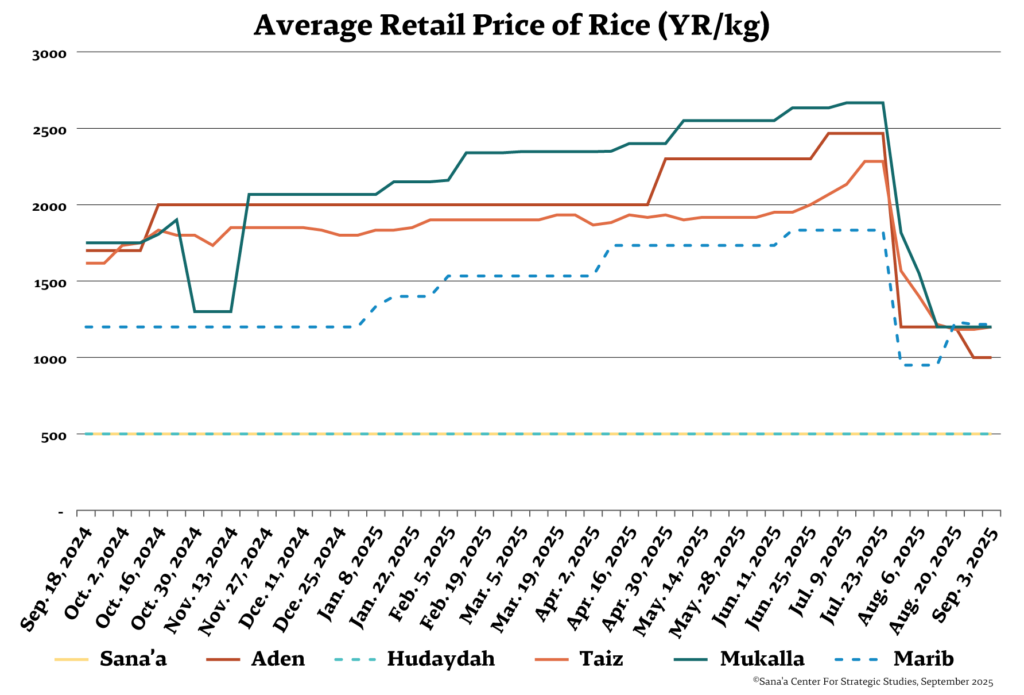

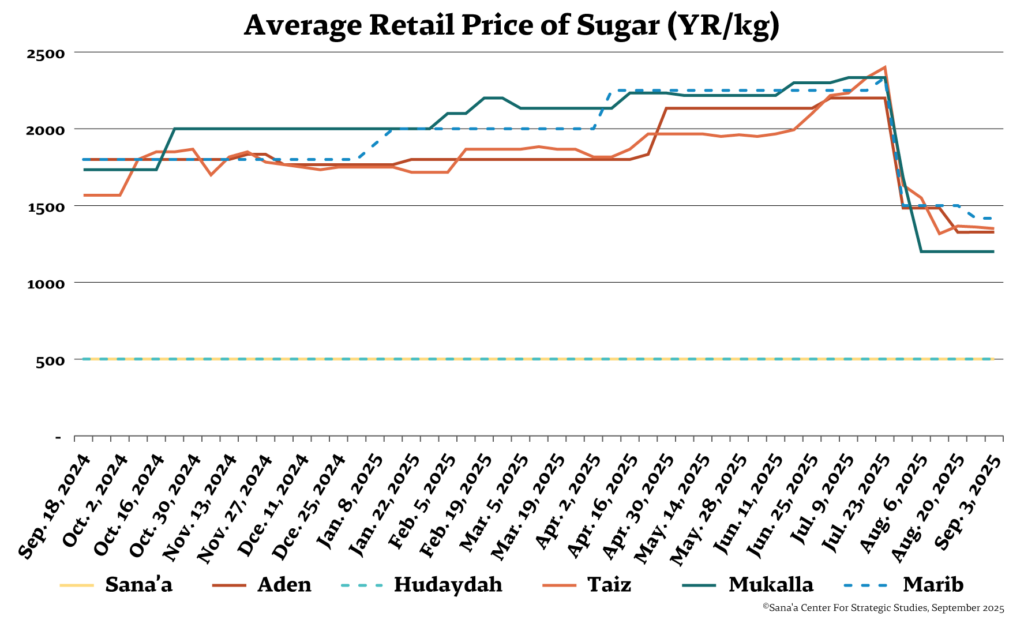

Food and fuel prices have witnessed a sharp decline in government-controlled areas following the rial’s recovery (see commodity price graphs below). Price reductions in Aden ranged between 20 and 40 percent for basic food commodities like wheat flour, rice, sugar, vegetable oil, and kidney beans. Beginning in August, local authorities conducted monitoring and inspection campaigns to ensure prices aligned with official price caps set by trade and industry offices.

Despite these efforts, price reductions have been inconsistent across governorates under government control. Commercial traders have been reluctant to respond to the rial’s sharp appreciation, as they perceive the rial’s recovery as temporary, and their current inventories of imports were purchased when the currency was weaker. Prices for most basic goods in Taiz remained relatively unchanged before falling by as much as 20 percent after officials conducted field visits.

In a statement, the Hayel Saeed Anam Group (HSA), Yemen’s largest trading conglomerate, warned against imposing lower prices without coordination with relevant authorities or genuine guarantees of exchange rate stability. The HSA claimed that ill-considered measures could lead to supply disruptions and widespread bankruptcy among manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers, as existing import commitments and hard currency payments had been made at higher exchange rates.

In mid-August, the Yemeni Petroleum Company in Aden announced price reductions of over 22 percent for both petrol and diesel. Prices dropped from YR1,550 to YR1,200 per liter for diesel and YR1,190 for petrol in Aden, Lahj, Abyan, and Al-Dhalea. Taiz, Hadramawt, and Al-Mahrah have also announced fuel price reductions. The price of petrol was down from YR1,430 to YR1,100 per liter in Taiz; in Al-Mahra, the price of diesel was set at YR1,325 per liter and petrol at YR1,050. Marib continues to sell locally refined gasoline at a heavily subsidized price of YR400 per liter. Conversely, its imported diesel sells for YR1,800 per liter and has not seen any price reduction.

Cooking gas prices have also been cut. The Yemen Gas Company issued a circular reducing gas prices across most government-controlled governorates. A 20-liter cooking gas cylinder is now YR6,025 in Aden, YR5,687 in Al-Mukalla, and YR6,338 in Al-Mahra. In Marib, the price is set at YR4,873 in the city and YR5,662 in the countryside.

Socotra is the exception. The price of a single gas cylinder has soared to over YR30,000, fueling a surge of public anger. Deputy Governor Issa Muslim denounced the archipelago’s exclusion from reductions of domestic gas prices, calling it a continuation of the marginalization that Socotra’s people have suffered for decades. There have been accusations of monopolistic practices against Emirati companies operating in Socotra, specifically ADNOC and the Eastern Triangle Company. In June, the Emirati companies increased the price of a 20-liter container of petrol to YR50,000 and a small gas cylinder to YR32,500. The Socotra National Conference called on the PLC and the government to compel the Eastern Triangle Company to match official prices elsewhere. The Socotra Reconciliation and Settlement Committee gave ADNOC until August 6 to comply with official price caps, threatening escalatory measures, including closing stations and imposing government pricing themselves, but the prices remained unchanged at the time of writing.

CBY-Sana’a Introduces New Coins and Banknotes

On July 13, the CBY-Sana’a issued a new 50-rial coin, stating it would not affect exchange rates or the economy, as it is intended solely to replace deteriorating banknotes of the same denomination. Two days later, the CBY-Sana’a announced the introduction of a new 200-rial banknote to replace damaged and worn-out 100, 200, and 250-rial notes.

In response, the CBY-Aden denounced the Houthis’ new currency issuances as “counterfeit, destructive, and a continuation of the economic war.” The CBY-Aden asserted that the Houthis were deliberately destroying Yemen’s financial system to loot savings and fund illicit operations. The bank warned citizens and financial entities against using the currency in order to protect their assets and avoid international sanctions. At a meeting in Aden, several European ambassadors voiced support for the CBY-Aden as the sole legitimate authority for issuing new currency, describing other operations as “illegal counterfeiting.”

The Houthis’ new 50-rial coin aims to replace YR5 billion in 50-rial banknotes, less than 1 percent of the overall supply of old rials. The larger 200-rial banknote, however, is intended to replace an estimated YR35 billion of worn-out 200 and 250-rial banknotes, over 2 percent of old rials. Their release also carries a hidden threat: it likely represents the first step before the printing of higher denominations. An uncalculated expansion of the monetary base could further erode confidence in the rial and destroy the monetary system.

Power Outages Spark Anger as Government Scrambles for Fuel

Many governorates in government-controlled areas experienced prolonged blackouts due to a shortage of fuel supplies to operate their power stations. Power cuts in Aden and Hadramawt reached up to 20 hours a day, compounding residents’ suffering during the hot summer.

The drastic reduction in electricity supply sparked public outrage in Hadramawt, leading to widespread protests. Demonstrations quickly expanded to the cities of Al-Shihr and Ghayl Bawazir, where protesters blocked the streets, criticizing the collapse of essential services and the deterioration of living conditions and local currency. Protesters raised banners demanding the resignation of Hadramawt Governor Mabkhout bin Madi, accusing the authorities of corruption and negligence in addressing the crisis.

The crisis stems from a confluence of factors. A critical shortage of fuel has limited electricity generation. The local authority accused the Hadramawt Tribal Alliance of being behind fuel supply disruptions at power stations and said the group should bear full responsibility for the deteriorating situation.

Years of neglect and lack of investment in the electricity infrastructure have contributed significantly to the current situation. Last summer saw similar protests as blackouts and living conditions became unbearable. The government has faced a barrage of criticism for its handling of the problem, and accusations of mismanagement and lack of transparency in the electricity sector abound. The government claims to spend US$100 million a month on fuel and power plant rentals.

With homes and businesses without power for extended periods, basic necessities like refrigeration and air conditioning become luxuries. The situation poses significant health risks, especially for vulnerable populations. The already fragile social fabric in government-controlled areas threatens to unravel entirely if the government is unable to find a durable solution.

Houthi Drug Trafficking Thwarted

The government reported a significant escalation in Houthi trafficking of illegal drugs between July and August, with major seizures thwarted on land and at sea. The largest seizure was reported by the Counter-Terrorism Service in Aden on August 23, constituting approximately 600 kilograms of cocaine. The drugs were hidden inside bags of sugar that arrived from a Brazilian port. The shipment was seized in Aden before it was reportedly scheduled to be transported to areas under Houthi control.

High-value narcotics were also seized on the border with Saudi Arabia, the primary consumer market for amphetamines in the Gulf. In mid-July, government authorities at the Al-Wadea border crossing announced they had thwarted a Houthi attempt to smuggle approximately 16,000 captagon pills. The drugs were hidden inside the buttons of women’s clothing loaded in a Toyota Land Cruiser, which was en route to Saudi Arabia from Houthi-controlled territory. The US Embassy in Yemen commended the seizure, calling it an important step in curbing the illicit activities that fund the group and threaten regional stability.

There have been similar seizures before. The operation came several days after the confiscation of 439 kilograms of narcotics from a boat off the coast of Hudaydah. This included 253 kilograms of hashish and 186 kilograms of methamphetamine (shabu). On July 6, government authorities at Al-Wadea thwarted an attempt to smuggle 13,750 captagon pills into Saudi Arabia in a truck coming from Houthi-controlled Sana’a. In June, authorities seized an estimated 1,530,300 narcotic pills smuggled inside another Houthi truck bound for Saudi Arabia.

Before President Bashar al-Assad’s ousting in December 2024, Syria was the world’s leading source of captagon with an amphetamine business estimated at US$10 billion, exceeding the country’s US$9 billion GDP. The seizure of large quantities of illicit drugs on the Yemeni-Saudi border could indicate a shift. Following the fall of the Assad regime, manufacturing capacity for captagon and other narcotic substances has likely been relocated to Houthi-controlled areas. This could allow the group to mobilize significant revenues through drug trafficking.

US Expands Sanctions on Houthi Networks

The US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) escalated its campaign to financially isolate the Houthis. It has issued two rounds of sanctions targeting the group’s revenue streams, procurement networks, and illicit trading. On June 22, the OFAC announced sanctions against two individuals and five entities[1] for their involvement in money laundering and illicitly importing petroleum products into Houthi-controlled territory, claiming the Houthis have coordinated with Yemeni businessmen to tax these petroleum imports, mobilizing hundreds of millions of US dollars annually to fund their activities.

The Amran Cement Factory was also sanctioned for money laundering and providing the Houthis with earnings. Since March 2025, the Houthis have diverted cement from Amran Cement Factory to the mountainous Sa’ada region in northern Yemen to build and fortify military bases and ammunition caches.

OFAC continued its pressure campaign, imposing new sanctions on Houthi revenue streams and procurement networks on September 11. These targeted 32 individuals and entities and four vessels in Yemen, the UAE, China, and the Marshall Islands,[2] which were accused of facilitating revenue streams, oil smuggling, and the illicit import of goods through Houthi-controlled ports.

One of these was the state-owned tobacco company. Revenue generated from the cigarette industry and associated taxes represents a significant source of income for the Houthis. In 2017, the Houthis effectively took control of the Kamaran Industry and Investment Company, using it to generate profits for themselves. There are indications that some Houthi leaders may also be involved in cigarette smuggling operations.

In response to the OFAC designation, Kamaran issued a statement repudiating the claims made against it and characterizing the sanctions as politically motivated. The company maintained that it had not violated any company laws or its articles of association and said it reserves the right to challenge the sanctions through legal channels. The sanctions threaten the company’s continued viability, with hundreds of families standing to lose their primary source of income.

The new sanctions are part of an intensive US campaign to suffocate the group financially, but the Houthis’ established black-market activities and trade with other sanctioned entities make it unlikely that the sanctions will erode their funding sources completely.

Houthi Authorities Impose Boycott and Energy Sector Sanctions

The Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Investment in Sana’a urged all traders to dispose of goods on an American-Israeli boycott list ahead of an upcoming deadline. Beginning October 5, the ministry will run field inspections and seize any remaining goods. On April 25, a directive issued by Mahdi al-Mashat, president of the Houthi Supreme Political Council, banned all American and Israeli products, giving traders a three-month grace period to comply. In July, an exception allowed banned goods held at the border until August 18 to clear customs, but the final deadline now forces traders to comply or face confiscation.

The boycott will impact already strained supply chains, affecting business and infrastructure projects, as well as small workshops and companies that rely on affordable, second-hand imported goods. Boycotted products include electronics, batteries, heavy equipment, cars, fuel, and engine oil, which are widely used in Yemen for transportation, construction, energy, and household purposes. The ban, combined with restrictions on imported goods that have locally produced equivalents, is expected to strain the economy further and increase costs for business operations.

On September 30, the Humanitarian Operations Coordination Center (HOCC) in Sana’a announced sanctions against thirteen entities, nine individuals, and two assets for their alleged involvement in the export of US crude oil. According to the HOCC, the designated parties are directly or indirectly involved in the “export, re-export, transport, loading, purchase, or sale of US crude oil.” The list included international oil companies such as ExxonMobil and Chevron.

- Among the most notable companies sanctioned was the Arkan Mars Petroleum Company for Oil Products Imports (Arkan Mars). Owned by Muhammad al-Sunaydar, who manages a vast network of petroleum companies between Yemen and the United Arab Emirates, it is one of Yemen’s most prominent petroleum importers. Arkan Mars Petroleum DMCC and Arkan Mars Petroleum FZE are UAE-based companies associated with Arkan Mars that have reportedly been involved in importing Iranian oil to Yemen. OFAC said “all three of the Arkan Mars companies coordinated the delivery of approximately US$12 million worth of Iranian petroleum products with the Persian Gulf Petrochemical Industry Commercial Company (PGPICC) to the Houthis via Ras Issa port in Yemen.” Saida Stone for Trading and Agencies (Al-Saida), owned by Yahya Mohammed al-Wazir, was sanctioned for similar illicit activities. Between November and December 2024, Al-Saida spent approximately 6 million euros to purchase bulk coal, presumably to import into Houthi-controlled areas. Al-Saida’s public advertisement of itself as a stationery wholesaler in Sana’a is at odds with these repeated large-volume coal purchases, behavior typical of a front company.

- OFAC sanctioned a number of revenue-generating entities, including the Kamaran Industry and Investment Company, Yemen’s largest tobacco producer, led by Mohammed Ahmed al-Dawla, and real estate company Shibam Holding, which OFAC said was being used by the Houthis to launder money and finance investments in the real estate and communications sectors. Among the individuals sanctioned were Abdullah Mesfer al-Shaer, associated with the General Holding Corporation for Real Estate and Investment, and Khaled Muhammad Khalil, head of the Economic Department of the Houthi Security and Intelligence Service. Khalil is known to manage acquisitions and facilitate money laundering for the Houthis, frequently utilizing Shibam Holding, with Al-Shaer playing a key role in these operations. The sanctions also targeted oil and fuel importers based in Hudaydah, Sana’a, and Sa’ada, including the Azal Company, Royal Plus Petroleum Derivatives Import, the Oil Primer Company, Sam Oil, and Al Faqih International. Overseas outfits supplying the Houthis with dual-use components and military-grade materials were also listed, most notably Chinese companies Guangzhou Nahari Trading, Shanxi Shutong, and Hubei Chica. Shipping companies were also named, including Tyba Ship Management, based in the United Arab Emirates, as well as Star MM Inc. and MT Tevel Inc., both registered in the Marshall Islands. Each is accused of providing the Houthis with financial, material, or technological assistance, or supplying goods and services that benefited the group or enabled its operations.