“Respecting God’s tenets, living in harmony, simplicity, and peace, and doing as our parents and grandparents did.” [1]

Socotra, a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site, has one of the most unique and isolated ecosystems in the world. Located off the coast of Yemen near the Horn of Africa, the Socotra archipelago sits at the crossroads of the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. The archipelago is home to incredible biodiversity: 37 percent of its 825 plant species are endemic. It is also home to rare trees, including the iconic dragon’s blood tree, and a diverse array of animals, including both terrestrial and marine birds, several of which are threatened species. In 1992, during the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Socotra was recognized as one of the world’s most pristine areas, unspoilt by degradation. The Yemeni government formally declared the Socotra archipelago a nature reserve through Republican Decree No. 275 of 2000, dividing it into 27 marine reserves and 12 terrestrial reserves. UNESCO declared it a Man and the Biosphere Reserve in 2003, and a World Natural Heritage Site in 2008.

For centuries, the people of Socotra have cultivated a close relationship with their environment, adapting to its character and utilizing its resources while making efforts to preserve it. The impact of climate change now poses the greatest threat to the Socotran way of life. In recent years, prolonged droughts and the devastating effects of cyclones, including Cyclone Chapala in 2015 and Cyclone Mekunu in 2018, have devastated the archipelago’s natural habitats, destroying reefs, causing soil erosion, and harming the islands’ endemic trees and plants. Cyclones in Yemen have increased in frequency, posing serious risks to the country’s vulnerable coastal populations.

In this photographic essay, we document the changes witnessed by the people of Socotra, capturing the impacts of climate change on their livelihoods and landscapes. We explore their stories to understand the extent of these effects on the archipelago, emphasizing the human and cultural experiences of the local people during this transformative period. Rapid climatic shifts have had far-reaching consequences in Socotra, from the changing landscape to the evolving anxieties of its residents.

With the outbreak of war in Yemen and the transformations that have taken place over the past decade, little research has been done and little attention given to the rapid effects of climate change on Yemen’s prized natural and cultural heritage. With its unique biodiversity, the Socotra archipelago serves as a compelling example of how climate change is reshaping the natural world and the lives of its inhabitants.

Life at Sea

“A time will come when the coast is empty of any fishermen, and the pastures are empty of sheep.” [2]

The sea carries a tale both cherished and painful for the people of Soctora. Since ancient times, it has been a source of sustenance during periods of hunger and drought, providing vital employment opportunities. Local folklore in Socotra highlights both the sea’s abundance and the threats associated with extreme weather events. Fouad Naseeb Saeed,[3] a local resident and Director of Research and the Marine Protected Areas Department at the Socotra branch of the Environmental Protection Authority, highlighted the extensive damage inflicted by cyclones on the livelihoods and equipment of fishermen.

Socotra currently lacks an early warning system to alert fishermen to impending extreme weather events, enabling them to secure their property and equipment before cyclones strike. In 2015, Cyclone Chapala damaged several boats, engines, and pieces of equipment, catching fishermen off guard. Just one week later, Cyclone Megh followed, causing further destruction.

Overfishing — much of it illegal — along with rising sea temperatures, has significantly affected traditional fishing practices in Socotra, leading to severe declines in catch. In the past, local laws and customs regulated fishing, but these are slowly disappearing. Studies examining the effects of climate change on Socotra’s marine life remain scarce due to a lack of resources.

Valleys

“Wadi Difarhu changed after the cyclones.”[4]

Sheikh Salem Hazmehi, a resident of Wadi Difarhu, reminisced about his childhood in this central valley, one of the most important in Socotra. “This valley used to be filled with shady trees, and we held all our gatherings here. One day, when I was young, the Sultan [from the Afrar Dynasty] came to this valley, and the tribes gathered here, bringing their goats. The goats were slaughtered, and the Sultan mediated conflicts between the residents of neighboring areas. After a few days, the Sultan left, and we returned to our homes here.”

Valleys, too, have been extensively damaged in Socotra. Once filled with trees, many of these wadis now resemble barren deserts due to the impact of cyclones, explained Hazmehi. “The rains were torrential, and the accompanying winds were severe; everything was destroyed,” he lamented. His house, which overlooked the valley, was destroyed during a cyclone; floods swept away parts of it. Pointing to a ruined home nearby, he said, “This house holds my memories. My whole life was here. I was born here, I got married here, and I lived my entire life here. But the cyclones came and took so much away, forcing me to move and build another house elsewhere.” A biodiversity expert working on Socotra warned that millions of years of biological evolution could be under serious threat from climate change.

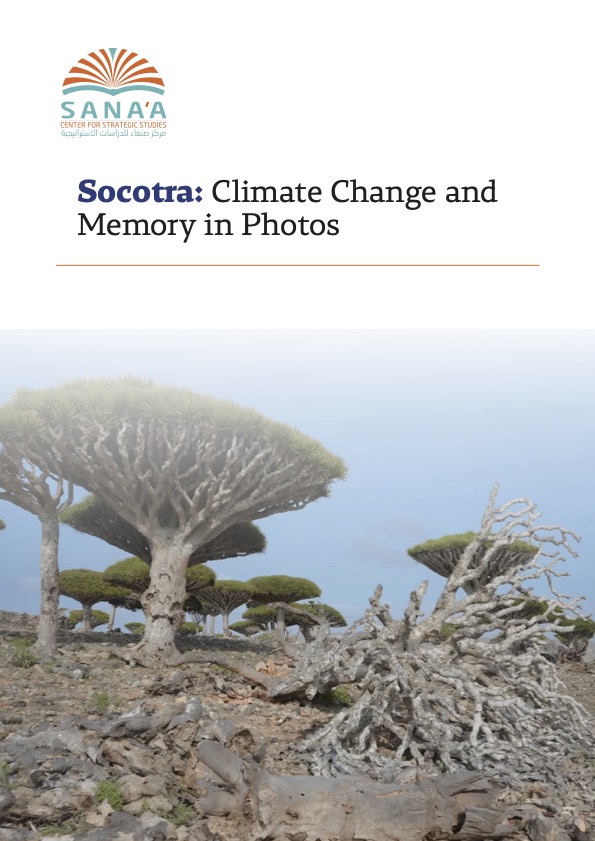

The Dragon’s Blood Tree

“The Dragon’s Blood Tree in the heart of Socotra.”[5]

Myths surround Socotra’s iconic Dragon’s Blood Tree (Dracaena cinnabari). One story tells of an uninhabited island. On the mainland, a sultan’s daughter fell ill, and despite their best efforts, doctors were unable to find a cure for her sickness. Finally, one of the doctors advised the sultan that there was an uninhabited island named Socotra, where a plant could be found that would cure his daughter. The sultan announced that any knight who dared to venture to that island and bring back the cure would marry his daughter. One brave knight stepped forward and sailed to Socotra. Upon arriving, he found that jinn guarded the island. He fought a battle with a jinni and managed to wound it. When the jinni realized it was injured, it fled to the mountains, bleeding. Wherever a drop of its blood fell, a Dragon’s Blood Tree sprouted. The knight returned to the mainland with the cure. The daughter recovered, and he married her. Together, they returned to Socotra, becoming the first inhabitants of the island.[6] The tree’s resin, known as Amsala, was used and exported in ancient times as a remedy to stop bleeding. Today, women from Socotra use it in cosmetics, and it is also sold to tourists.

A 2022 UNESCO report on Socotra highlights how cyclones have destroyed entire groves of the Dragon’s Blood Tree.

Palm trees

“We preserve palm trees because, to us, they are blessed and sacred.”[7]

Among Socotra’s residents, palm trees are blessed. In Socotri folklore, a legend recounted by Sheikh Hassan al-Qaisi, from the western Socotran village of Qaiso, goes as follows: “In a small village in western Socotra, water was scarce. A roster was in place to regulate the use of the little water available, allocating one day to each person to water their livestock and store enough for their household until their next turn. One quiet day, a woman from the village was collecting water. While she was busy filling the waterskin (a traditional water container made from animal skin), a man on horseback approached her. He asked for water to quench his thirst, and she gave him some. He then asked for water for his horse, and she obliged. He then asked to wash himself, and she gave him more water. Then he asked to wash his horse, and once again she fulfilled his request. “‘You are a generous woman,’ said the man on horseback. ‘I ask you to return to this spot early tomorrow morning, and you will find it filled with springs of water and transformed into a forest of palm trees.’ The woman returned home, and the next morning she went back to the spot to find it full of springs and palm trees. Since then, this place has been called Aihan Masbiha, (springs that appeared suddenly in the morning). The legend says the man was an angel from the heavens.”

For generations, palm trees have been a source of survival during droughts, providing sustenance for the local population. Climate change and increasingly violent cyclones are putting these blessed trees at risk.

The Imtah Tree

“Trees in Socotra, including the Imtah, have suffered significant damage”[8]

Grazing in Socotra is largely uncontrolled. Goats roam freely except during the dry season, when they require supplemental feeding because drought has reduced grass and shrubs. Different regions have varying practices of providing fodder. In the northern coastal strip, shepherds still rely on the Imtah tree to feed goats during drought. Historically, all shepherds relied on this tree more to feed their goats, but as barley began to be imported, many stopped depending on it.

The Imtah tree (Euphorbia arbuscula) is a native species of Socotra and was once widespread in many areas. Over the past decade, cyclones have severely impacted many endemic trees, leaving large areas barren. The Imtah tree resembles the Dragon’s Blood Tree. A local joke among Socotris recounts an incident where a senior Yemeni state official from the mainland visited the island for the first time. He spotted the Imtah tree on the road from the airport to Hadibo and sat under it, mistakenly thinking it was a Dragon’s Blood Tree, which only grows at higher altitudes.

In an environmental report on Socotra, the Associated Press highlighted that in 2015, an exceptionally intense double cyclone uprooted thousands of trees, some over 500 years old. The devastation continued in 2018 with the arrival of Cyclone Mekunu.

The Frankincense Tree

“Many forests have lost 70 percent of their frankincense trees due to cyclones.”[9]

The frankincense tree (boswellia sacra) is a rare tree that thrives in the mountainous regions of South Arabia, particularly in Oman and Yemen. The tree produces frankincense, the most prized commodity traded along the ancient incense route. Of the 24 known species of Boswellia, 11 are found only on Socotra. The majority of Socotri frankincense is sold and exported, usually through mainland Yemen via Mukalla, before reaching foreign countries. The rest is sold locally to tourists. “The name of the frankincense tree in Socotri is Sam’anah or Saqtrana,” said Saleh Omar,[10] a resident from the Homhil Natural Reserve area located in northeastern Socotra, known for its unique flora and extensive forests of endemic trees. “This place used to be a forest of frankincense trees, but cyclones and strong winds destroyed many of them, turning the area into a devastating scene filled with trees lying on the ground.” Saleh Omar took the initiative to plant nearly 700 frankincense trees, stating, “I couldn’t bear to see this area without its frankincense trees.” Saleh also noted that they had recently discovered the tree’s resin to be beneficial for patients with heart disease, and that it was used in the rituals of Socotri traditional healers when treating their patients.

Goats

“Our lives have been greatly affected, and bit by bit, we are abandoning our beautiful culture and heritage.“[11]

Goats have been associated with Socotris since ancient times and have become an integral part of their rural philosophy. Estimates suggest there are about 480,000 goats on Socotra. Amer Salem Saeed,[12] a shepherd in Qalansiyah district in western Socotra, says, “We love our goats because they are our livelihood. We take pride in them and cherish them, calling them ‘maghsab di Allah‘ (consecrated by God). Goats have always been of great importance to us; they provide milk, save us from hunger, and it is how we honor our guests. We consider them blessed animals that we also use to pray to God, and He often answers us.”

Saleh bin Dohr from the Liskah area of west-central Socotra,[13] noted how extreme weather has led to the decline and disappearance of a variety of endemic shrubs grazed by goats. “Plants were growing in the pastures that locals would eat at times, and they were delicious, but these have entirely vanished.” Another shepherd[14] from the same area listed the shrubs that goats used to eat, some of which were also suitable for human consumption, including aishhir, sayfut, talaliya, kabdeneh, jafahin, mgkherhem, reiba, mandawrab, and many others. “Ninety percent of these shrubs have disappeared in recent years and no longer grow.” Goat herds were heavily impacted during the cyclones due to heavy rains, resulting in the loss of many animals. After the cyclones, herding patterns and practices underwent significant changes due to alterations in soil and pastures, the disappearance of many shrubs, widespread damage to the natural environment, and fallen trees.

Honey

“Socotri bees are facing the threat of extinction.“

Socotri honey is among the finest types of honey in Yemen, a country renowned for an ancient beekeeping tradition that goes back thousands of years. In Socotra, honey used to be sold in markets inside Shamlan plastic water bottles (Yemen’s national water brand), and exported to mainland Yemen and the Gulf. With the rise of tourism, some shops have started marketing honey in plastic containers with a label and their logo.

Socotri beekeepers used to extract honey from hives located in cliffs, rocks, and large trees, with bees foraging on various native tree species on Socotra, such as Mathen, Dhad, Lasfa, and Imtah. Recurrent cyclones have also affected Socotra’s bees. The storms caused numerous trees to fall, which in turn affected the archipelago’s bees. In many areas of Socotra, bees have now almost completely disappeared. Ahmed Abdullah,[15] a beekeeper from the Hajhir mountains in eastern Socotra, stated, “In the past, at the beginning of the season, bees would come to their homes and hives in large trees or rocks in the valleys and mountains. But the cyclones destroyed the trees, the valleys, and everything else. The bees’ way of life has now changed.” The effects of climate change could have a dire impact on beekeeping, with dire implications for people’s livelihoods and this ancient craft.

Ancient Building Methods

“The houses built in the old way were warm.”

In addition to its biodiversity, climate change is impacting the archipelago’s unique architectural heritage. In Socotra, the ancient method of building houses and stone huts, called ṭād ḍāfrī, involved stacking single stones one on top of another, rather than using double-layered walls. The roof was constructed by laying large tree branches as beams from one side to the other. Then, the roof was packed with smaller branches, and finally, a specific type of soil was applied to prevent water from leaking onto the floor. Locals found this method reliable, but it cannot withstand violent weather brought on by climatic shifts. The people of Socotra have had to adapt to a new, modern method of building that relies on cement and iron, which contrasts sharply with Socotra’s natural, wild environment.

The extreme weather events of 2015 and 2018, in particular, took a heavy toll on Socotra’s architectural heritage, including damage to national monuments such as the 19th-century Alha Mosque. The World Monuments Fund, an organization dedicated to preserving Socotra’s built heritage, has acknowledged the threat that climate change poses to the biodiversity, architectural heritage, cultural traditions, and local livelihoods of the Socotra Archipelago, noting that its rich living heritage deserves recognition and protection.

An Uncertain Future

“A change may occur in Socotra where the spring wind arrives during the autumn season.”[16]

The words of Sheikh Saad Suleiman Harsi,[17] a goat herder from the village of Harswa in western Socotra, reflect the unsettling realities of climate change for Socotra’s communities, highlighting how the impact of climate change is not just environmental but also profoundly human: “A long time ago, it rained for about a week. Many goats died, and some people died too. Before the rains of that year, a drought had lasted for many years. That year was known for the rains of ‘di-Raboo’ (the Wednesday Rains). I think the rain started on a Wednesday and continued until the following Wednesday. The situation then was not at all like what we have experienced in recent years. I have never heard any of the elders discussing rain in such an unusual manner. The cyclones destroyed everything and disrupted the way of life in Socotra. We used to believe that Socotra would always be fine, but recently I have had deep anxiety for Socotra, and I fear these disasters will happen again.”

This photo essay was produced as part of the Yemen Peace Forum, a Sana’a Center initiative that seeks to empower the next generation of Yemeni youth and civil society activists to engage in critical national issues.

- Interview with Saleh Bin Dohr, a goat herder and resident of the Liskah area of Socotra, June 29, 2025.

- “Ad tawhah laken kheleh debal mesh’arek wa ‘ad shadheren adihum debal gikeih basen.” A folkloric chant sung in the Socotri language by fishermen while out at sea.

- Interview with Fouad Naseeb Saeed, Director of Research and Marine Protected Areas Department at the Socotra branch of the Environmental Protection Authority, June 22, 2025.

- Interview with Sheikh Salem Hazmehi, a resident of Wadi Difarhu in Socotra, June 25, 2025.

- Jess Craig, “Saving the Dragon’s Blood: How an Island Refused to Let a Legendary Tree Die Out.” The Guardian, November 12, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/nov/12/saving-dragons-blood-island-refused-let-tree-die-out-socotra-yemen

- As told by Salem al-Kibani, resident of Diksam plateu, central Socotra, June 26, 2025.

- Interview with Sheikh Hassan al-Qaisi, a local resident and the Sheikh of the Qaiso area in western Socotra, June 26, 2025.

- Interview with Ahmed Mohammed Ahmed, a sheperd from the Haibaqh area of Hadibou distrit, June 26, 2025.

- Interview with Salem Hamdiyah al-Suqutri, a frankincense tree arborist, June 26, 2025.

- Interview with Salih Omar, a resident of the Homhil area, a nature reserve for frankincense trees in northeastern Socotra, June 21, 2025.

- Interview with shepherd Amer Salem, a resident of the Shata area in western Socotra, June 27, 2025.

- Ibid.

- Interview with goat herder Saleh Bin Dohr, a resident of the Liskah area in west-central Socotra, June 29, 2025.

- Interview with Abdullah Ahmed, a shepherd from the Liskah area in west-central Socotra, June 29, 2025.

- Interview with Ahmed Abdullad, a beekeeper from the Hajhir mountains in eastern Socotra and head of the Ma’thin Honey Association, June 23, 2025.

- “Harsi harsi khalfi amdten. Lilbeden men kharfi arees lamdiah la’ali.” Saying by Nabhi, a Socotri sage.

- Interview with Sheikh Saad Suleiman Harsi, a goat herder from the village of Harswa in western Socotra, June 28, 2025.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية