Executive Summary

Shabwa’s oil sector has developed in fits and starts. Its first commercially viable oil reserves were discovered in 1987 when the governorate was still part of South Yemen. In 1990, South Yemen united with North Yemen to form the Republic of Yemen, which enlisted foreign energy companies to help develop the nascent oil industry. This included the construction of a pipeline running from northern Shabwa to the governorate’s Arabian Sea coast, and over the next 15 years a growing number of foreign energy firms and state-owned companies tapped new oil fields and further expanded production. Shabwa’s annual oil output peaked in 2010 at more than 25 million barrels (about 70,000 barrels per day), before plummeting to about 8 million barrels the following year amid the political and security vacuum that accompanied Yemen’s Arab Spring uprising.

Throughout most of the history of Shabwa’s oil sector, the interests of foreign energy companies and the central government have taken precedence over the concerns of local communities, such as a fair distribution of revenues, environmental impacts, and oversight issues. In 2018, Shabwa became the first governorate to resume oil production for exports after operations were suspended in 2014. The revival of exports marked a new beginning for Shabwa’s local authority, which negotiated an agreement with the central government in Aden to retain 20 percent of oil revenues generated from the governorate. Although the revenues have increased the local authority’s capacity to fund development projects and other priorities in the governorate, most of the major decisions in Shabwa’s oil sector continue to be handled by foreign energy companies and the Aden-based Ministry of Oil and Minerals.

Shabwa’s latest oil boom has spawned new environmental problems, in particular due to the increased reliance on the governorate’s dilapidated oil pipeline, which has contaminated the water wells and soil of farming communities along its path. The central government is responsible for the maintenance and repair of oil infrastructure, but late 2022 saw oil exports suspended nationwide once again after Houthi drone attacks targeted oil export terminals in Shabwa and Hadramawt. The Houthi-imposed embargo on hydrocarbon exports has exacerbated the government’s dire economic situation by depriving it of its main source of revenue, which has, among other negative ramifications, prevented needed investment in the development and maintenance of Shabwa’s hydrocarbon industry.

To continue the momentum in reviving Shabwa’s oil sector, the internationally recognized government should restart oil production in blocks where known reserves have been neglected by foreign energy companies since the late 2000s. This can be facilitated by encouraging local participation and buy-in through the creation of a Shabwani oil company, similar to those existing in Marib and Hadramawt. A small oil refinery should also be established in Shabwa to help meet domestic demand and reduce Yemen’s overall reliance on fuel imports. Finally, the government should publish oil sector news and statistics on a more consistent basis to reduce misconceptions about oil production levels and increase transparency regarding ownership.

Introduction

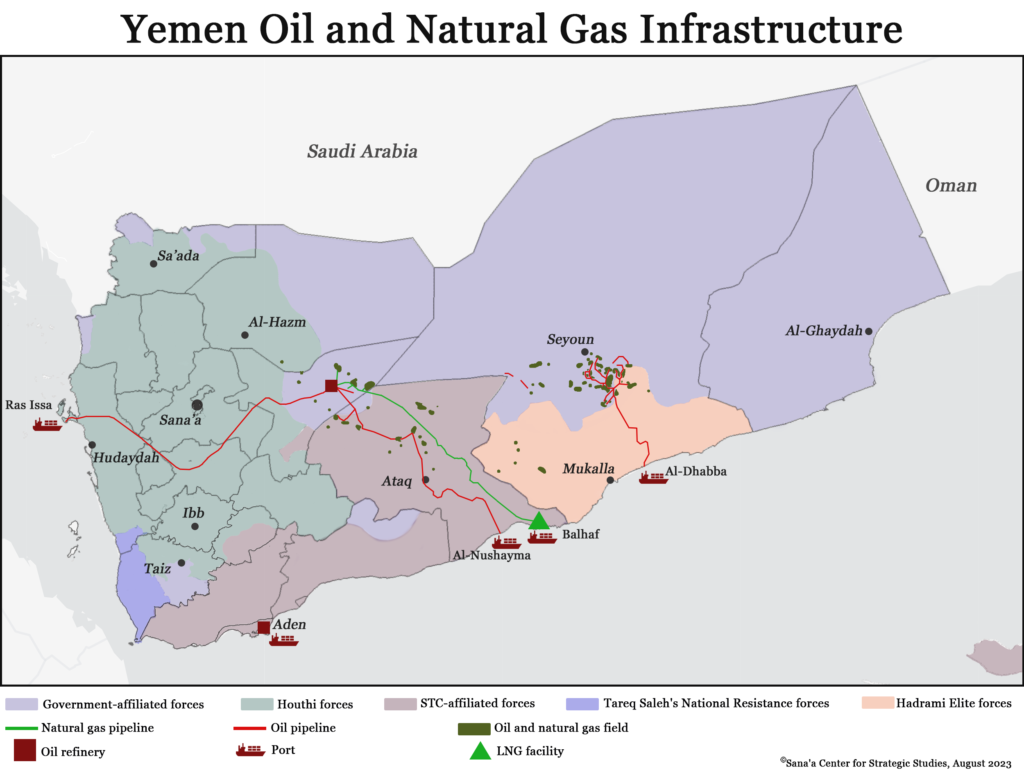

Strategically located in south-central Yemen, Shabwa governorate is part of what has been dubbed the Yemeni government’s “triangle of power,” an area encompassing Shabwa and neighboring Marib and Hadramawt governorates that contains all of the country’s oil and gas production.[1] Control of this region has allowed the government to remain relevant despite losing both the capital Sana’a to Houthi forces allied with former President Ali Abdullah Saleh in September 2014 and the interim capital Aden to the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) in August 2019. In 2018, Shabwa resumed oil production after a near-complete shutdown of Yemen’s sector in early 2015 as the conflict escalated, and the local authority negotiated an agreement with the central government to keep 20 percent of oil revenues generated in the governorate.[2] However, the interests of foreign oil companies and Yemen’s central government continue to dominate the governorate’s oil sector. As a result, Shabwa’s population is still unable to maximize the economic and development benefits of its lucrative natural resource and bears the brunt of environmental problems associated with its extraction and transport.

This policy brief examines the historical development of Shabwa’s oil sector, the complex network of foreign and domestic stakeholders involved in its governance, and how diverging interests and lack of coordination have undermined productivity. With these considerations in mind, and based on the priorities of local stakeholders, the policy brief explores the challenges and potential benefits of establishing a state-owned, locally-run oil company in Shabwa similar to Safer Exploration and Production Company in Marib and PetroMasila in Hadramawt. On the upside, a state-owned oil company would be better positioned to maintain operations during security and political instability that has routinely spooked foreign energy companies. The downside of a Yemeni-operated oil company in Shabwa is the potential for corruption and bloated bureaucracy to erode productivity and cut into profits. These considerations are weighed against historical developments and current trends in formulating recommendations for Shabwa’s oil sector.

Methodology

On August 17-18 2022, a diverse group of local stakeholders attended a workshop in Shabwa’s capital Ataq to assess the governorate’s most urgent challenges. The workshop was not designed to be a forum on the oil sector, but this quickly became the case as oil has been central to work and life in Shabwa for many years. Among the main outcomes of the workshop[3] was the insight that increased local management and control of the oil sector was a key economic and development priority for the governorate.[4] One of the authors attended a follow-up event in January 2023 where the topic was raised again. As such, this policy brief aims to examine the viability of prioritizing local management by analyzing the prevailing institutional setup of Shabwa’s oil sector, which has historically been dominated by foreign companies and the central government.

Interviews with officials from the Ministry of Oil and Minerals, employees with foreign and domestic oil companies, academics, and crews and management at oil facilities were carried out between January and April 2023. To supplement information from these interviews, a qualitative analysis of the historical and contemporary environment of Shabwa’s oil sector was conducted in order to better understand its development over time and foreign companies’ role therein. This included reviewing archival sources, regional newspapers, and existing data published by the Yemeni government.

Throughout this process, two key research challenges arose: First, a lack of verifiable and current data on Shabwa’s oil sector, which made quantifying developments over time difficult. To overcome this, public information was shared with informed sources in Shabwa’s oil industry, allowing experts to provide alternative or supplementary data sets. The second challenge involved a general reluctance among interviewees to discuss certain topics, particularly the issue of corruption. As a solution, unless they requested to be publicly cited, interviewees were granted anonymity to allow them to speak freely and mitigate the possibility of reprisal.

The Historical Development of Shabwa’s Oil Sector

In the late 1980s, Yemen experienced a small boom in oil exploration. New geological surveys identified promising Jurassic-era reserves, and energy companies from all over the world scrambled to negotiate exploration and production concessions.[5] Brokering concession agreements was particularly delicate, as Yemen was then divided between the Yemen Arab Republic, or North Yemen, and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, or South Yemen.[6] Exploration was taking place on the seam between these two nations, with North Yemen handling negotiations for contracts in Marib governorate, and South Yemen developing the oil sector in Shabwa.[7]

In 1987, Soviet energy company Technoexport was the first to discover oil reserves in Shabwa in Block 4 of the Eyad area in Jardan district, just north of the governorate’s capital Ataq.[8] This was the first commercially viable oil discovery in South Yemen; oil had been discovered in the North three years earlier.[9] The limited oil supply produced under Technoexport was trucked to the port city of Aden for refining, as neither pipelines nor port infrastructure existed in Shabwa at the time.

On May 4, 1988, North and South Yemen agreed to demilitarize their border in order to establish a joint oil exploration area.[10] Both fledgling nations were struggling economically and in dire need of new revenue streams. To share the profits and administer the area, they formed a joint-holding company, the Yemeni Investment Company for Oil and Minerals (YICOM) in 1989.[11] Development of the oil fields in Shabwa under Technoexport was moving much slower than development in North Yemen, which was run by the US-based Hunt Oil Company.[12] In August 1990, negotiations with the Soviet Union demanding increased infrastructure investment completely fell apart and the contract with Technoexport was suspended.[13] YICOM had already opened bidding for new concessions in Shabwa, issuing permits in June 1990 for four international oil companies, Chevron and Phillips from the United States, Crescent from the United Arab Emirates, and Italy’s Agip, ramping up the foreign development of Shabwa’s oil fields.[14]

By May 1991, a year after the unification of North Yemen and South Yemen formed the Republic of Yemen, additional oil discoveries and investments in the oil sector led to the construction of the Bir Ali pipeline in Shabwa. Upon inauguration, the pipeline transferred about 10,000 barrels per day (bpd), representing about one-sixth of the pipeline’s capacity, from Block 4 to the Al-Nushayma export terminal in Shabwa’s southern Rudum district on the Arabian Sea.[15] In 1996, a consortium of energy firms led by Jannah Hunt Oil Company discovered Shabwa’s largest oil reserves.[16] The discovery was in Block 5, located in the Wadi Jannah area of Usaylan district in the northwestern part of the governorate. Production from this site peaked at more than 65,000 bpd in 2000, gradually dropping to about 17,000 bpd in 2012.[17] The major shareholders in Block 5 are state-owned YICOM and the Kuwait Foreign Petroleum Exploration Company (KUFPEC), each of which owns a 20 percent share of the concession. Total, Exxon Mobil, Jannah Hunt, and Newco Enterprises each own 15 percent of Block 5.[18]

Commercially viable reserves were again discovered in 2003, this time in Block S1 in the Damis area of Usaylan district. Explorations were led by a consortium of companies: Vintage Petroleum from the US held 61.9 percent at the time of discovery; the Canadian company Transglobe Energy held 20.6 percent; and the Yemen Company (YCO) held 17.5 percent.[19] In 2005, US company Occidental Petroleum acquired Vintage Petroleum,[20] and in 2016, the assets of both Occidental and Transglobe in Block S1 were acquired by Australian Petsec Energy, which sold 75 percent of its stake in the block in 2020 to British company Octavia Energy, the current operator.[21] Production started in 2004 and peaked at nearly 12,000 bpd in 2008, dropping to about 830 bpd in 2012.[22]

In 2005, the discovery of commercially viable oil deposits was announced in Block S2 in the Al-Uqlah area in the district of Erma in northeastern Shabwa by a consortium led by the Austrian company OMV (44 percent) and China’s Sinopec (37.5 percent concession).[23] Extraction began in 2006 and peaked at around 19,000 bpd in 2010 before dropping to less than 700 bpd in 2011.[24]

When oil from Block S2 was connected to the Bir Ali pipeline in 2006, total oil production in the governorate was nearly 20.6 million barrels. Overall production then steadily increased by about 1-1.5 million barrels per year, reaching an all-time peak of more than 25.6 million barrels in 2010 (about 70,000 bpd).[25] However, by the following year, the Arab Spring-inspired uprising in Yemen led to the resignation of longtime President Ali Abdullah Saleh, and administrative disruptions and insecurity caused annual oil production to drop by more than two-thirds — to about 8.1 million barrels. During the first two years of Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s presidency, from 2012 to 2014, Shabwa’s annual oil production was not tracked as his administration centralized data into one national index for oil production, temporarily halting regional data collection.[26]

Yemen’s oil production was disrupted in the months after the Houthi took over Sana’a in September 2014 due to instability surrounding the political upheaval, and nationwide production nearly completely shut down following the Saudi-led coalition military intervention on March 26, 2015. Oil exports were also suspended.[27] Most of Shabwa’s oil at the time was trucked northward to Marib’s Safer company where it entered the pipeline leading to the Ras Issa oil export terminal in Hudaydah governorate on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast. Hadramawt restarted production in August 2016.[28] The largest oil producer in Yemen, Hadramawt governorate also has the advantages of being far from frontlines and having a domestic oil company, PetroMasila, in charge of production.[29] Shabwa resumed production in April 2018, after the Austrian company OMV assessed the security situation in northeast Shabwa and asked staff who left Yemen to return to the facility.[30] Production resumed at drastically reduced levels. In 2022, Shabwa had an output of 1.1 million barrels, or about 3,000 bpd.[31]

However, the indefinite closure of Ras Issa and the year-and-a-half closure of the Al-Dhabba export terminal on Hadramawt’s Arabian Sea coast refocused attention on the existing infrastructure in Shabwa. Given its relative stability, distance from the frontlines, and proximity to export markets in Asia, Shabwa’s Arabian Sea coast emerged as a new focal point for oil exports. In July 2018, trucks started to transport oil from Shabwa’s Block S2[32] to facilities in Block 4, where they entered the Bir Ali pipeline to the Al-Nushayma’s export terminal.[33] Realizing Shabwa’s potential, the Yemen-owned Safer Exploration & Production Company in neighboring Marib’s Block 18 and Canadian company Calvalley Petroleum from Hadramawt’s Block 9 started sending their oil through the pipeline to the export terminal in Shabwa months later.[34]

In addition to oil reserves, significant natural gas reserves have been found in the Safer area of Marib. In 2005, the Yemeni government signed a deal with a consortium of foreign companies to process the gas reserves. In Yemen’s largest foreign investment project to date, US$4.5 billion[35] was invested in a Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) processing and export facility in the port town of Balhaf, adjacent to Bir Ali port, in Shabwa’s Rudum district.[36] The first LNG shipment was exported in November 2009 but the facility was closed in 2012 amid the instability that followed Yemen’s 2011 uprising.[37] The processing facility has remained closed throughout the war, having been taken over by Al-Qaeda until 2016 and used as a prison and military base for UAE-backed forces since 2017.[38] Although Shabwa has not extracted natural gas deposits of its own, most of the LNG pipeline traverses Shabwa en route to the LNG refinery and export terminal at Balhaf. The project was forecasted to generate a total of about US$30-50 billion for the Yemeni government over 20-25 years.[39] Its continued closure, in part due to its use as a military base by UAE-backed forces, became a source of contention between former Shabwa Governor Mohammed Saleh bin Adio and UAE forces stationed at the facility.[40]

Governance of Shabwa’s Oil Sector

With a history complicated by the political and economic ambitions of many nations, multiple Yemeni administrations, corporations, tribes, and armed forces, the governance of Shabwa’s oil sector echoes deeply in, and far beyond, the governorate. Management of the sector too often suffers from a narrow focus on the interests of foreign corporations and the central government at the expense of all else. Concessions are signed between the government and oil companies, which discuss the rights to produce oil, ratios for dividing profits, rights for exploration, investment in, and maintenance of infrastructure. This has relegated important considerations such as environmental impact, oversight mechanisms to guarantee infrastructure maintenance, community development, local hiring practices, and the local authority’s ability to control the distribution of resources outside of the governorate. The following section breaks down these competing interests and lays the groundwork for areas of most concern for policymakers.

Foreign and Domestic Companies

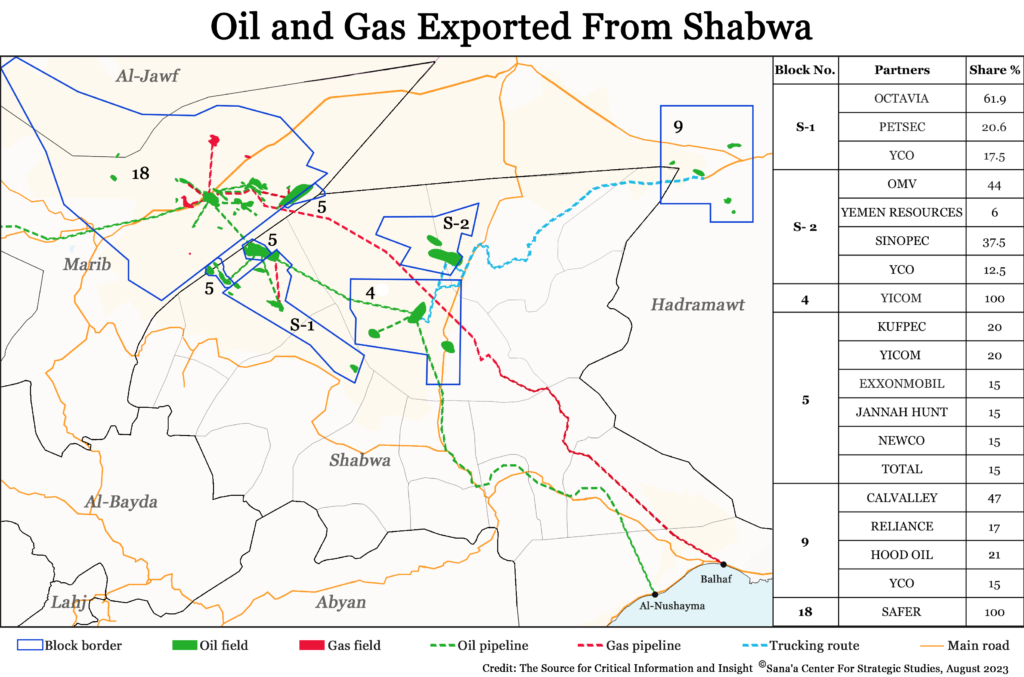

Shabwa has four oil-producing blocks, which are operated by a consortium of foreign and local companies. As shown below, current concessions allow foreign companies to take the largest share of ownership over production.

Block 5, the highest producing in the governorate, is operated by Petromasila and owned by KUFPEC, YICOM, Total, Jannah Hunt, Exxon Mobil, and Newco Enterprises. Block 5 is located in northwest Shabwa and includes five oil fields. Block 5 also contains a large untouched gas reserve, awaiting investment and extraction.[41]

Block S2, the second largest producing in the governorate, is operated by OMV and owned by OMV, Sinopec, YCO, and Yemen Resources. S2 is located in the Erma district of northeastern Shabwa, and this complex fractured basement reservoir[42] holds three oil fields.[43]

Block S1 ranks third in production and is operated by Octavia Energy, and is owned by Octavia Energy and Petsec Energy. It is located in the Damis area of Usaylan district, northwest Shabwa, and contains two oil fields.[44]

Block 4 is the least productive in Shabwa and is fully owned and operated by YICOM. In the Eyad area of Jardan district, just north of the governorate’s capital Ataq, Block 4 has three oil fields.[45] It has not been fully explored, and veteran experts in the field suggest that it might hold significant untapped reserves that might eclipse other blocks in the governorate if exploited correctly.[46]

The Local Authority, Central Government, Tribes, and Regional Actors

Beyond competing corporate interests, Shabwa’s oil industry is still trying to overcome a legacy of highly centralized government control. Since restarting production in 2018, local authorities in Marib, Shabwa, and Hadramawt exercised increased autonomy. Shabwa, like Hadramawt and Marib, negotiated an agreement with the central government to keep 20 percent of all hydrocarbon revenues generated within the governorate’s borders.[47] Still, foreign oil companies typically discuss all major decisions with the Aden-based Ministry of Oil and Minerals. This includes plans to sell shares of a particular block or determine which processing and export facilities to which their oil production will be sent.[48]

As head of the local authority, the governor of Shabwa has significant influence over oil companies’ day-to-day operations. Often, the governor has a strong say over which infrastructure projects the oil companies will finance. Some foreign oil companies have supplied funding for public services, building hospitals, schools, and roads, upgrading wastewater disposal infrastructure; and completing other public works throughout Shabwa.[49] These investments vary widely from company to company and are often viewed by local communities as insufficient. Design and implementation of these projects are often carried out by the Governor’s Office, along with the Ministry of Oil and Minerals’ local branch. The governor also advises foreign oil companies of potential security issues that might threaten operations — a role with surprising power. At times of emergency, this can even extend to the ability to halt oil-producing activity in the governorate altogether. For example, in January 2015, after Houthi forces kidnapped Ahmed bin Mubarak, the current foreign minister and then-chief of staff to President Hadi, while he was on his way to present a draft of the new Yemeni constitution, then-Shabwa governor Ahmed Bahaj ordered a halt in oil production in the governorate.[50] A more recent example of the governor’s power was illustrated by the combined efforts of former governor Mohammed Saleh bin Adio and current governor Awadh bin al-Wazir al-Awlaki, who co-signed an agreement in February 2023 to build Shabwa’s first natural gas power plant. The 60 MW power plant is to be built in Al-Uqlah, and will be powered by unused natural gas reserves captured from oil production sites.[51]

Also influencing oil companies in Shabwa are the different tribes who have long lived in the areas surrounding oil fields and their infrastructure. Realizing that barriers to oil companies’ operations quickly inspire government actions, tribal members regularly interfere with production efforts. By organizing demonstrations, blocking roads leading to oil fields, or sabotaging equipment and infrastructure, tribal members have found they can increase the likelihood that their demands are met.[52] Foreign oil companies’ lack of awareness of local norms, customs, and complex kinship networks has also caused tension with tribes, who often have their own competing interests. For example, one oil company’s hiring practices sparked a tribal dispute in December 2012 which resulted in 12 deaths after members from one tribe were hired as guards to protect a section of the LNG gas pipeline without asking for input or offering similar sources of income to other tribes in the area.[53] The resulting feud has expanded to a legacy of hostilities between the two groups that is still ongoing today.

The development of Shabwa’s oil sector has been slowed by the unstable security situation, which adds chaos and unpredictability to basic system operations. In addition to contributing to the instability that led to the shutdown of oil production from 2015-2018,[54] Houthi forces subsequently advanced into Shabwa in late 2017 and threatened oil infrastructure before being driven out of the governorate in January 2022.[55] In response to incursions by Houthi forces and an expanded Al-Qaeda presence in Shabwa during the early months of the war, the UAE formed the Shabwani Elite forces, whose mission was to help coalition forces retake and secure territory in Shabwa. The Shabwani Elite ultimately became part of a power struggle in the governorate that deepened divisions within the Saudi-led coalition and culminated in the takeover of Ataq city and the surrounding oil fields in August 2022 by UAE-backed forces. The changing of the guard led to new sources of instability for oil companies operating in the area.[56]

Fog of War Fuels Dysfunction

Even after the necessary infrastructure was built in 1991 to export oil directly from Shabwa via Al-Nushayma, local politics prevented all but Shabwa’s least producing block, Block 4, from using the pipelines from 1994 to 2018. Instead, the majority of extracted oil was trucked to neighboring Marib and then piped twice the distance to Ras Issa until it was closed in 2015. This was vastly more expensive than using Shabwa’s existing pipe infrastructure, as trucking oil traditionally costs between 5 and 10 times more than piping.[57] However, politics trumped efficiency here, as trucking the oil to Marib and then exporting the oil via pipeline to Hudaydah ensured that the central government controlled oil exports, and prevented southern nationalists from gaining too much economic and political leverage from the strategic resource. After Shabwa’s oil production resumed in 2018, Yemeni authorities decided to transport nearly all of it through the Bir Ali pipeline to Al-Nushayma. At the export terminal, Aboveground Storage Tanks (AST) can hold more than 600,000 barrels of oil and are currently storing oil from four different blocks: Safer’s Block 18 in Marib; OMV’s Block S2 in Shabwa; YICOM’s Block 4 in Shabwa; and Calavalley’s Block 9 in Hadramawt. In 2019, construction began on a pipeline to move oil from the Jannah Hunt Oil Company’s Block 5 to YICOM’s facility at Block 4, where it is planned to join the pipeline leading to Al-Nushayma export terminal.[58] Oil exports were expected to have doubled once the pipeline became operational.[59]

But just months after the new pipeline was tested for capacity, Houthi drones attacked a ship offloading oil at Bir Ali port in southern Shabwa on October 18, 2022.[60] Less than one month later on November 9, a second Houthi drone attack targeted a ship offloading diesel at Qana port. Because both Bir Ali and Qana ports are located just east of the Al-Nushayma export terminal, these attacks effectively ceased international exports from the terminal.[61] Due to the Houthi threats, oil exports nationwide were completely halted in late 2022.

Block 4: Untapped Potential

Paradoxically, disruptions to oil operations could be a positive development by leaving oil reserves and the ability to access them untouched. This is thought to be the case in Block 4, or the “granny block” as it is referred to in the Yemeni oil sector, where Technoexport began production in 1987. By 1991, the block (then under management by Saudi Arabia’s Nimr Petroleum company)[62] reached nearly 10,000 bpd, with plans to increase output to 25,000 bpd in subsequent years. However, when Yemen’s 1994 civil war and technical difficulties caused production to drop to zero in 1995 and stay at around 1,200 bpd from 1996-2001, the potentially productive block became dormant. After Nimr Petroleum pulled out of the project in 2001 and YICOM took over, production fell even lower to 500 bpd, leaving even more potential for future exploitation.

Because of this, experts agree that Block 4 still contains the majority of its reserves and thus has great untapped potential.[63] However, cascading crises — from political unrest to engineering failures — have prevented development and access to these reserves, despite a series of efforts by foreign companies to stabilize production over the years. The last of these efforts was in 2008 by South Korea’s KNOC, but given the political unrest throughout Yemen, KNOC was unable to import the necessary equipment to restore production in a timely manner, and the company eventually decided that the investment risk was too high and abandoned the project in 2012.

In general, Block 4 is indicative of a larger problem with foreign oil companies in Yemen. Unlike local initiatives, foreign companies often do not make plans for long-term sustainable operations of oil blocks. They instead prioritize extracting as much oil as possible as quickly as possible, without consideration for damage to the environment or existing infrastructure or wells. They also frequently abandon projects when profits are threatened, leaving all outstanding problems for the next company to deal with. Oil wells cannot be temporarily abandoned, and neglect makes many wells unusable. Oil well restoration involves a lengthy and costly process called a ‘well workover.’[64] If a well must be abandoned, the correct process is to seal the well, ensure that no leakage is occurring, and dismantle and remove all equipment from the site. This process is highly technical and costly, and it has not yet taken place at Block 4.

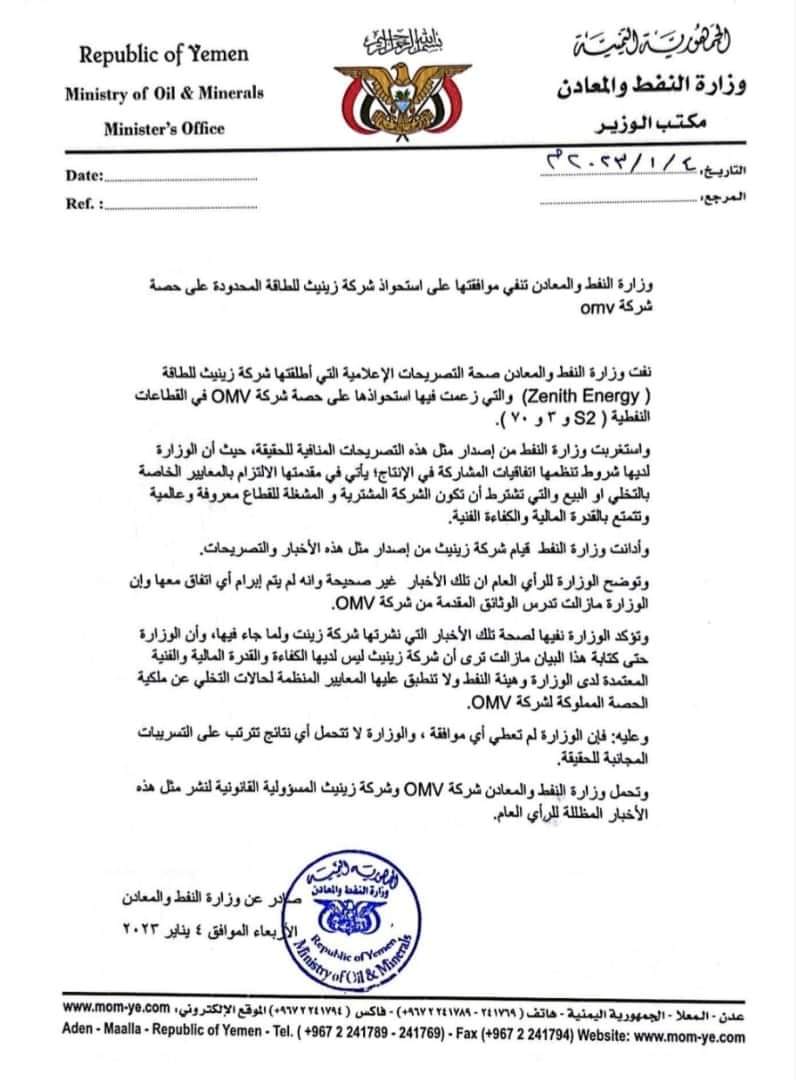

OMV’s Misreported Takeover

Dysfunction can also come in the form of corporate overreach, as companies attempt to take advantage of perceived gaps in the regulation of Yemen’s oil sector. This was the case in early January 2023, when Zenith Energy, a company headquartered in Canada,[65] announced on Twitter that one of its subsidiaries had negotiated the purchase of Austrian company OMV’s stake in Shabwa’s Block S2, and OMV’s contract to explore Block 3 and Block 70.[66] The following day, on January 4, the Aden-based Ministry of Oil and Minerals issued a press release stating that no such deal had been completed, as any concessions would have to be authorized by the ministry, adding that Zenith did not have the technical or financial resources to be considered a viable replacement for OMV. The ministry warned of potential legal action against both Zenith and OMV for the release of misleading information to the public. On February 1, a committee formed by parliament to investigate the rumored changes in ownership of these oil blocks — without the central government’s approval — found that the Ministry of Oil and Minerals had rejected a November 2022 request from OMV to sell its concession to Zenith due to the latter’s lack of sufficient technical expertise and financial resources. The committee noted its surprise that Zenith would publicly announce the acquisition of these blocks without official approval, overtly disregarding the government’s jurisdiction.[67] The incident highlighted the dysfunctional nature of Shabwa’s oil sector, stemming in part from unclear regulations and the willingness of foreign companies to exploit them.

The Oil Sector’s Developmental, Social, and Environmental Impacts on Shabwa

The more than three decades of exploration and production by different foreign oil companies in Shabwa has had a lasting impact on the local community, both positive and negative. Although the governorate’s oil production long contributed a major portion of the central government’s national budget, Shabwa received little in return during the rule of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh. Aside from the 1991 pipeline which connected Block 4 to the Al-Nushayma export terminal, Shabwa saw no major infrastructure projects and almost no economic development in the following decades. That changed in 2019 after former governor Bin Adio negotiated a 20 percent share of the governorate’s oil sales to be set aside for local development.[68] The arrangement, which has continued until today, has visibly changed the governorate in unprecedented ways. Local development projects using oil revenues have been used to help to fund Shabwa’s first university,[69] complete the construction of a long-awaited general hospital,[70] connect several districts to the electricity grid for the first time,[71] and build tens of kilometers of paved roads in the capital Ataq, as well as in remote districts.[72] The construction of Shabwa’s first natural gas power plant is scheduled to begin in the coming months.[73]

However, not all oil sector activities have been positive for Shabwa. Farming communities, in central and eastern Shabwa in particular, have been affected by oil leaks that have contaminated their water wells and soil.[74] Maintenance and repair of oil infrastructure is the joint responsibility of YICOM and the Ministry of Oil and Minerals, and repairs are complicated by the fact that both of these entities are in dire financial straits and often unable to perform their duties unless the pipelines are functional and producing income, creating a self-exacerbating problem. Much of the leakage has occurred since 2018 as a direct result of a sudden influx of oil being pumped through the dilapidated, 32-year-old pipeline traversing farmlands from YICOM’s Block 4 in northern Shabwa to the Al-Nushayma export terminal.[75] Prior to 2018, the pipeline was used to transport much smaller volumes of oil and lacked regular maintenance.

Only after these leaks began visibly polluting farms and water wells did YICOM and the Ministry of Oil and Minerals initiate repairs on the most damaged segments of the pipeline in the Ghurair area in Al-Rawdah district.[76] Further repairs were most recently conducted in early 2023.[77] While the repairs were welcomed, locals have requested further government regulation to mitigate the long-term effects of oil pollution on Shabwa’s soil and water. Chief among these requests is the proper disposal of contaminated soil using licensed companies with the requisite technical expertise. Preventative efforts and timely responses to future leaks – guaranteed through the establishment of an emergency unit staffed by financially and legally motivated companies – are also a top priority for locals, given that the quantity of oil flowing through the pipeline is expected to expand as additional blocks enter service, increasing the risk of leakage.

Current Trajectory of Shabwa’s Oil Sector

Shabwa’s oil sector is still dominated by foreign companies with extractive business models. These companies terminate their contracts with the government with little notice, stop production without fully understanding Yemen’s security risks, and often don’t resume production for years — unlike domestic companies such as Safer Exploration and Production Company in Marib and PetroMasila in Hadramawt, which were faster at resuming operations during the war. Such problems are common with foreign companies working in war-torn countries, but most foreign concessions in Shabwa are coming to, or have already come to, an end.[78] In coming years the government will have to decide whether to renew their contracts or handle the blocks in a way that promises more reliable production at a time when stable energy and resources are essential.

Experts estimate that moving the production tasks to government-owned companies will save the government an estimated 30 percent of profits from exported oil that have been paid to foreign companies as royalties.[79] In addition to royalties, foreign companies are also reimbursed for their operating costs. This arrangement made sense in the early decades of oil production when Yemen needed outside expertise and investment to develop the nascent oil sector. However, because no new infrastructure projects are currently needed for oil production or transport, and outside expertise regarding production is no longer required, the moment has never been better for Shabwa’s oil sector to finally follow the Marib and Hadramawt model. The establishment of a domestic Shabwani oil company could help the governorate plan for the future and minimize any resistance that might come from local political or tribal leaders if the blocks were given to another domestic company.

Media attention surrounding the misreported sale of OMV’s production blocks also inspired an investigation by the Yemeni parliament,[80] which revealed divisions among politicians: several voices in the Yemeni government want to continue allowing international oil companies to run Shabwa’s oil blocks arguing that foreign oil companies are more efficient and stable in the production of oil, while others are in favor of launching a local initiative.[81] Nonetheless, the general tone of the parliamentary debate, coupled with a lack of transparency around foreign companies’ attempts to acquire and sell shares in Shabwa’s oil blocks, indicates that foreign companies are there to stay. Beyond OMV, the rapid and almost unpublicized acquisition of Block S1 by Petsec and then Octavia Energy demonstrates that the Yemeni government has a long way to go if it intends to fulfill the dream of building a Shabwani oil company.

Regardless of ownership, Shabwa’s many promising exploratory blocks still need attention. The long history of civil wars, tribal conflict, and political turmoil in Shabwa and across Yemen have prioritized a grab-and-go approach, meaning the expensive – yet necessary – process of oil exploration remains unfinished. As Yemeni policymakers look forward, they should take into consideration foreign companies’ tendency to prioritize profits over sustainability and instead prioritize deals that invest in Shabwa for years to come.

Conclusion

Shabwa’s oil sector still holds great potential for Yemen’s future. After the war ends, Yemen will need steady sources of revenue to subsidize reconstruction. This is something that Shabwa could offer — but only if oil production and export can be stabilized. Many of the major steps have already been taken, as infrastructure is already in place, and is owned and operated by the central government. Oil wells have been drilled, pumps installed, and pipelines run from Shabwa to the nearby Al-Nushayma port where AST containers are ready for use. From there, oil can be loaded onto oil tankers and exported. Experts agree that Shabwa still contains reservoirs of untapped potential.[82] With Shabwa’s intact reserves, the exploration zones have been identified and significant investments have already been sunk into drilling. The largest obstacle to seizing the many opportunities in Shabwa’s oil sector is instability.

Each break in production and stoppage of exports diminishes the efficiency and profitability of the sector’s operations. Without a consistent flow of cash to balance payments, maintenance becomes inadequate. With deficient maintenance and irregular use of existing infrastructure, the sector requires ever greater investments. Shabwa, and all of Yemen, needs oil production to function regardless of the political circumstances. Without it, instability causes a series of system failures, generating a negative feedback loop of lost opportunity with dire implications across Yemeni society.

Shifting management of the Shabwa oil sector away from foreign-directed leadership to local managers could have tremendous long-term benefits for the sector’s production, profitability, and development on local, regional, and national levels. Instead of extracting as much profit as possible, local managers are incentivized to plow profits back into the sector and region, which would benefit all of Yemen. Local operational staff are also a better fit, as they are more reliable during these uncertain times. A reorientation toward training and retaining local operational staff will develop an adaptive and motivated workforce able to maintain the sector’s labyrinthine infrastructure of wells, pipes, and derricks. Finally, giving Shabwa’s oil sector local leaders and staff would promote more local buy-in and build resiliency.

Recommendations

Restart Oil Production and Exploration

Promising discoveries have been made in Shabwa’s oil exploration blocks in the years before the Arab Spring but they never evolved into oil-producing projects. The Yemeni government should make a plan to resume the final steps of production for these blocks or use legal means to terminate concession contracts and negotiate new exploration or production concessions if foreign companies are unresponsive.

Shift Towards Domestic Actors

The oil sector in Yemen should encourage domestic production in Shabwa, as is the case in Marib and Hadramawt. This will help to avoid any disputes or grudges about job distribution or contracting opportunities that might lead to unrest among Shabwa’s local tribes and local oil sector workers. Policymakers should consider the potential benefits of creating a Shabwani oil company.

Improve Communications and Transparency

The government should publish information on the oil sector in official outlets on a timely basis to prevent confusion surrounding ownership changes and unknown oil production levels. Although the quality of data is unlikely to reach pre-war levels in the near term, available data should be made public on a timely basis.

Localize Oil Refining

A quick and sustainable solution is needed to address frequent fuel shortages in Shabwa and Yemen as a whole. Because oil is not refined within Shabwa, the governorate must import refined fuel from abroad, leaving the oil-rich region without the resources to solve its own fuel problems. To solve this, the Ministry of Oil and Minerals should construct a small oil refinery in Shabwa, similar to that in Marib, preferably at Block 4 because of its vicinity to other production blocks, in order to refine a portion of production for Shabwa’s and neighboring governorates’ needs at a reasonable price.

Prevent Damage to the Local Environment and Livelihoods

Taking precautions to prevent negative ecological ramifications from oil production is a must, particularly as the Soviet-era pipeline to the Arabian Sea passes through fertile and spring water-rich lands in southeast Shabwa. The Ministry of Oil and Minerals should develop protocols, including dedicated teams, to respond quickly to any leakages. This should involve hiring specialized companies to repair pipelines and remove and rehabilitate contaminated water and soil as a long-term investment in the health of the local environment and residents and the future sustainability of Shabwa as a route to export Yemeni oil abroad.

This policy brief was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, in partnership with Saferworld, as part of the Alternative Methodologies for the Peace Process in Yemen program. It is funded by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO).

- Ammar al-Aulaqi, “The Yemeni Government’s Triangle of Power,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 9, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/11542

- Omar Saleh Yaslm BaHamid, “Wartime Challenges Facing Local Authorities in Shabwa,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 10, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/11641

- The workshop was organized by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies in partnership with Saferworld as part of the Alternative Methodologies for the Peace Process in Yemen program, funded by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO).

- “Sana’a Center Workshop Tackles Urgent Issues in Shabwa,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, August 19, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/news/18511

- “Historical Overview [AR],” Yemen Ministry of Oil and Minerals (YICOM), accessed April 28, 2023, https://mom-ye.com/site-ar/نبـذة-تاريخـية/

- Robert Burrowes, “The Yemen Arab Republic: The Politics of Development, 1962-1986,” Routledge, 2016.

- Brian Whitaker, “The Birth of Modern Yemen,” Al-Bab, 2009, https://al-bab.com/birth-modern-yemen-chapter-4

- “Historical Overview [AR],” YICOM, 2023.

- In 1984, Yemen’s first oil deposits were discovered in nearby Marib governorate.

- Nada Choueiri, Klaus-Stefan Enders, Yuri V Sobolev, Jan Walliser, and Sherwyn Williams, “External Environment: Politics, Oil, and Debt,” in: “Yemen in the 1990: From Unification to Economic Reform,” International Monetary Fund, 2002, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781589060425/ch02.xml

- Sharif Ismail, “Unification in Yemen: Dynamics of Political Integration 1978-2000” Master’s Thesis, University of Oxford, 2007, https://users.ox.ac.uk/~metheses/Ismail Thesis.pdf

- “Historical Overview [AR],” YICOM, 2023.

- “Yemen-USSR Dispute Results in Suspension of Production from Shabwa Fields,” Weekly Middle East Oil & Gas News and Analysis (MEES), Vol. XXXIII, No.44, August 6, 1990, http://archives.mees.com/issues/1140/articles/40653

- “Yemen Awards Two More Concessions at Shabwa,” Weekly Middle East Oil & Gas News and Analysis (MEES), Vol. XXXIII, No.40, July 9, 1990, http://archives.mees.com/issues/1136/articles/40561

- “The Middle East and North Africa 2003 – 49th Edition,” Europa Publications, London and New York, 2003, p. 1227, https://bit.ly/3raewLU

- Jannah Hunt Oil is not a subsidiary of the US-based Hunt Oil Company. It is owned fully by Singapore-based WellTech Energy PTE. Ltd; “About Us,” Jannah Hunt Oil Company, Accessed June 15, 2023, https://www.jhocyemen.com/about-us-2/

- “Average daily oil production (barrels) from Block 5 Jannah until October 2012,” Petroleum Exploration and Production Authority of Yemen, unpublished report viewed by author.

- “Block 5,” Yemen’s Petroleum Exploration and Production Authority website, accessed June 25, 2023, https://pepaye.com/page/67

- “Block S1,” Yemen’s Petroleum Exploration and Production Authority website, accessed June 25, 2023, https://pepaye.com/page/71

- “Occidental to Buy Vintage,” New York Times, October 14, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/14/business/occidental-to-buy-vintage.html

- “Appendix 4E and 2021 Annual Report,” Petsec Energy Ltd, February 24, 2022, p. 5, https://www.aspecthuntley.com.au/asxdata/20220225/pdf/02491870.pdf

- “Average bpd produced at Block S1 until 2012,” Petroleum Exploration and Production Authority of Yemen (unpublished report viewed by author).

- “OMV to develop field on Yemen’s Block S2,”Oil and Gas Journal, January 19, 2006. https://www.ogj.com/exploration-development/article/17280143/omv-to-develop-field-on-yemens-block-s2

- Interviews with veteran oil and gas engineer Mohsen Abdelhaq and Shabwa-based officials from the Ministry of Oil and Minerals, January-March 2023.

- Data provided during interviews with oil and gas engineers and Shabwa-based officials from the Ministry of Oil and Minerals, January to March 2023.

- “Crude oil production in Yemen 2013-2022 [AR],” Studies and Economic Media Center, 2023.

- Farouk Kamali, “The ban paralyzes Yemen’s exports [AR],” The New Arab, May 16, 2015,www.alaraby.co.uk/الحظر-يشلّ-صادرات-اليمن; “Resolution 2216 (2015),” United Nations Security Council, April 14, 2015, p. 5, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/103/72/PDF/N1510372.pdf?OpenElement; Michael Knights, Alex Almeida, “Gulf Coalition Targeting AQAP in Yemen,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Policy Watch 2613, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/gulf-coalition-targeting-aqap-yemen

- “The Minister of Oil announces the resumption of Yemen’s production and export of oil from the Masila fields,” Saba Net, August 11, 2016, https://www.sabanew.net/story/ar/7982

- Rafiq Latta, “Yemen Oil Export Restart Hinges on Saudi-Houthi Talks,” Energy Intelligence, February 17, 2023. https://www.energyintel.com/00000186-6012-de95-a7ae-6336ba2f0000

- “Austrian firm boosts Yemen oil production,” MEED, November 20, 2018, https://www.meed.com/austrian-firm-boosts-yemen-oil-production/

- Author’s interview with an official in the office of the oil and minerals ministry in Shabwa, February, 15, 2023.

- Block S2 in Shabwa is operated by Austrian company OMV. “OMV to develop field on Yemen’s Block S2,” Oil & Gas Journal, January 19, 2006. https://www.ogj.com/exploration-development/article/17280143/omv-to-develop-field-on-yemens-block-s2

- “The Ministry of Oil announces the success of the first export of crude oil through the port of Rudum in Shabwa [AR],” Saba Net, July 31, 2018, https://www.sabanew.net/story/ar/36638

- “The oil ministry restores oil production and gains the trust of foreign companies,” Saba Net, December 27, 2019, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/57331. When larger volumes of oil started flowing through Shabwa’s pipeline, following the addition of Safer’s and Calvalley’s production in 2018, engineers discovered numerous leaks because for about 27 years the pipeline had been exclusively used for Block 4’s low volume of oil production and lacked regular maintenance and repair. Safer was exporting about 10,000 bpd and Calvalley about 3,000 bpd through the pipeline prior to the October-November 2022 Houthi drone attacks against oil export infrastructure along Yemen’s southern coast. As a result of the ongoing halt in exports, the pipeline remains inactive at the time of publication of this policy brief. Interviews with employees at YICOM and the Al-Nushayma export terminal, April 2023.

- “Project Overview,” Yemen LNG Company [AR], accessed April 25, 2023, https://www.yemenlng.com/ws/en/go.aspx?c=proj_overview

- The consortium consists of French oil company TotalEnergies (39.6 percent ownership and the project’s technical leader), US-based Hunt Oil Company (17.2 percent), Yemen Gas Company (YGC) (16.7 percent), South Korea’s SK Innovation (9.6 percent), and other minor stakeholders. “Shareholders,” Yemen LNG Company, accessed April 25, 2023, http://www.yemenlng.com/ws/en/go.aspx?c=ylng_share

- Mohammed Mukhashaf, “Yemen gas pipeline blown up, output halted after drone attack” Reuters, March 31, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-yemen-qaeda-drone-idUKBRE82T1DW20120330

- Michael Knights, Alex Almeida, “Gulf Coalition Targeting AQAP in Yemen,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Policy Watch 2613, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/gulf-coalition-targeting-aqap-yemen; Louis Imbert, “A Total site used as a prison in Yemen [FR],” Le Monde, November 7, 2019, https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2019/11/07/un-site-de-total-utilise-comme-prison-au-yemen_6018350_3210.html

- “FAQs,” Yemen LNG Company [AR], accessed April 25, 2023, https://www.yemenlng.com/ws/ar/go.aspx?c=proj_faq

- Louis Imbert, “The gas war in southern Yemen [FR],” Le Monde, December 4, 2020, https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2020/12/04/dans-le-sud-du-yemen-ruee-sur-le-magot-gazier_6062186_3210.html

- “Block 5,” Yemen’s Petroleum Exploration and Production Authority website, accessed June 25, 2023, https://pepaye.com/page/67. Note: This section includes the last publically released data published on PEPA’s website, but expert interviews suggest PEPA data is not current.

- Basement reservoirs occur when oil or gas has moved into older and more porous metamorphic or igneous rocks. This type of rock typically does not have enough void space for economically viable oil production, but natural fractures can increase the volume of oil reservoirs, making this type of reservoir an interesting prospect in the oil industry.

- “Block S2,” Yemen’s Petroleum Exploration and Production Authority website, accessed June 25, 2023, https://pepaye.com/page/73

- “Block S1,” Yemen’s Petroleum Exploration and Production Authority website, accessed June 25, 2023, https://pepaye.com/page/71

- “Block 4,” Yemen’s Petroleum Exploration and Production Authority website, accessed June 25, 2023, https://www.pepaye.com/page/65

- Interviews with experts in Shabwa’s oil sector and current and former engineers at Block 4, March-May 2023.

- “Shabwa receives $21 million from its share of oil exports [AR],” Saba Net, July 7, 2019, https://www.sabanew.net/story/ar/51472

- Interview with an official at the Shabwa office of the Ministry of Oil and Minerals, April 9, 2023.

- See, Nadwa Al-Dawsari, Daniela Kolarova, Jennifer Pedersen, “Conflicts and Tensions in Tribal Areas in Yemen,” Partners for Democratic Change International, 2011, pp. 17-18, https://partnersbg.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2011-Yemen-Conflict-Assessment-.pdf

- “Houthi abduction prompts Yemen to turn off oil taps,” The National, January 18, 2015, https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/houthi-abduction-prompts-yemen-to-turn-off-oil-taps-1.111045

- “Bin Al-Wazeer signs a memorandum to establish a 60 MW gas powered electric station”. Official statement, February 19, 2023, https://shabwa-gov.com/archives/9880

- Oil pipe sabotaged in Shabwa [AR], Reuters, December 23, 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/oegtp-yemen-pipeline-sk3-idARACAE9BM0EH20131223

- “Tribal mediation seeks to stop clashes that resulted in 12 deaths last week in Shabwa [AR],” Almasdar Online, December 19, 2012, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/94422

- Casey Coombs, Majd Ibrahim, and Nasser al-Khalifi, “Shabwa: Progress Despite Turmoil in a Governorate of Competing Identities,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 19, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/11930

- Fatima Abo Alasrar, “The Houthis’ retaliation for Shabwa,” Middle East Institute, January 19, 2022, https://www.mei.edu/publications/houthis-retaliation-shabwa#:~:text=In less than 10 days,districts that they had occupied

- “Shabwa.. Soldiers cut the road in front of oil tankers [AR],” Al-Harf28, September 20, 2022, https://alharf28.com/p-78033. The protesters stopped tankers coming from Al-Uqla to Marib governorate, as well as those heading to the Block 4 storage tanks, from which oil is then sent to Al-Nushayma port.

- “Transporting Oil: Why Pipelines Still Rule,” Forbes, May 13, 2016, https://www.forbes.com/sites/tortoiseinvest/2016/05/13/transporting-oil-why-pipelines-still-rule/?sh=3c2647a12dc9

- “Yemen to build new oil pipeline and storage tanks,” Middle East Business Intelligence, January 6, 2019, https://www.meed.com/yemen-build-new-oil-pipeline-storage-tanks/; Also see, “Al-Oud talks about a package of projects that will be implemented this year to develop the oil sector [AR],” Saba Net, November 5, 2019, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/49471

- Interviews with veteran oil and gas engineer Mohsen Abdulhaq and Shabwa-based officials from the Ministry of Oil and Minerals, January-March 2023.

- “Governor’s statement on Houthi drone strike targeting oil port [AR],” Hadhramaut TV, October 21, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GKs2foNNqKs

- Oil fields in Shabwa are still supplying a limited amount of derivatives to domestic power plants in Yemen.

- “Yemen Government Approves Nimr Agreement with Arco,” MEES, December 9, 1991, http://archives.mees.com/issues/1003/articles/36895

- Interviews with experts in Shabwa’s oil sector and current and former engineers at Block 4, March-May 2023.

- “Energy Glossary: Well Workover,” Schlumberger, Accessed June 20, 2023, https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/w/workover

- “About,” Zenith Energy, Accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.zenithenergy.ca/about/

- Zenith Energy, Twitter post, “Zenith is pleased to announce that Zenith Netherlands has entered into a SPA with OMV Exploration and Production to acquire 100% of the outstanding share capital of OMV Yemen…,” January 3, 2023, https://twitter.com/zenithenergyltd/status/1610242484315078657

- Almawqea Post, “Almawqea Post publishes the text of the parliamentary committee’s report on the sale of shares of some contractors in some oil sectors [AR],” Facebook, February 2, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/almawqeapost/posts/559904902832215; The committee also noted a request by OMV in May 2020 to sell its stake in multiple blocks to a company called SEPC. That request was also denied on the grounds that the new company lacked sufficient technical and financial capacity to operate the oil fields. Almawqea Post, “Almawqea Post publishes the text of the parliamentary committee’s report on the sale of shares of some contractors in some oil sectors [AR],” Facebook, February 2, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/almawqeapost/posts/559904902832215; The committee also noted a request by OMV in May 2020 to sell its stake in multiple blocks to a company called SEPC. That request was also denied on the grounds that the new company lacked sufficient technical and financial capacity to operate the oil fields.

- “Shabwa receives $21 million from its share of oil exports [AR],” Saba Net, July 7, 2019, https://www.sabanew.net/story/ar/51472

- “Bin Adio monitors the progress of rehabilitating and furnishing the headquarters and the medical college of Shabwa University [AR],” Saba Net, November 16, 2021, https://www.sabanew.net/story/ar/81093

- “Shabwa governor inaugurates phase one of Shabwa’s general hospital [AR], May 5, 2022, https://www.sabanew.net/story/ar/86404

- “Connecting Al-Talih district to the electric grid from Al-Uqlah station [AR],” Saba Net, July 14, 2020, https://www.sabanew.net/story/ar/64294

- “Shabwa’s governor initiates the desert road project costing $6 million [AR” March 12, 2020, https://www.sabanew.net/story/ar/60061

- “Signing a memorandum to established a 60 MW gas-powered electric station in Shabwa [AR],” Ministry of Electricity and Energy, https://moee-ye.com/site-ar/2363/

- Interviews with locals from the affected areas on April 15, 2023, and an unpublished geological survey report from the University of Aden’s College of Oil and Minerals in Shabwa seen by the authors, March 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Interview with an engineer working in Shabwa’s oil sector, April 17, 2023.

- Interviews with veteran oil engineer Mohsen Abdulhaq, March 2023.

- Ibid.

- For screen shots of the report, see Almawqea Post, “Almawqea Post publishes the text of the parliamentary committee’s report on the sale of shares of some contractors in some oil sectors [AR],” Facebook, February 2, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/almawqeapost/posts/559904902832215

- Interviews with local officials and experts in Shabwa’s oil sector, April 2023.

- Interviews with experts in Shabwa’s oil sector and current and former engineers at Block 4, April 2023.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية