The Sana’a Center Editorial

FSO Safer: Why Are We Still Waiting?

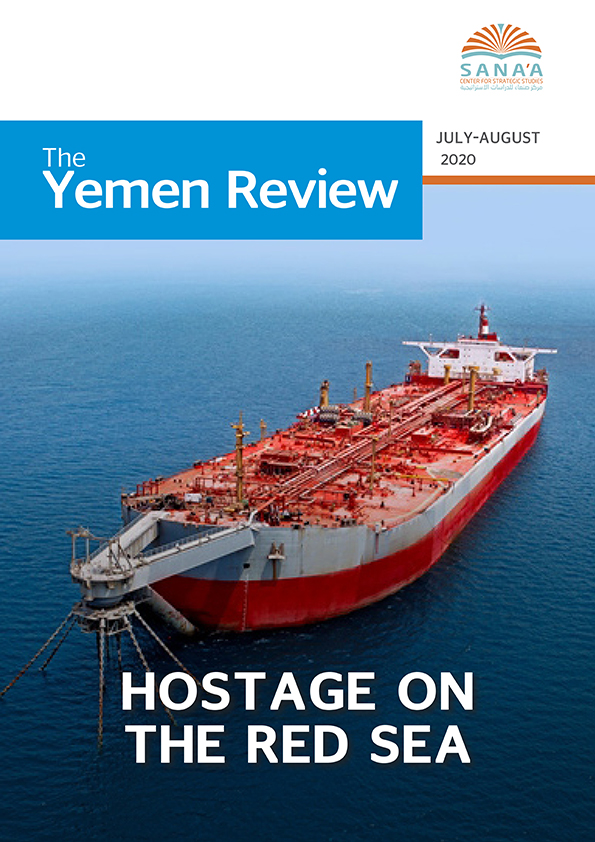

The devastating explosion at the port of Beirut, Lebanon, in August should instill a sense of urgency among all stakeholders in Yemen regarding the gigantic floating bomb just offshore of Hudaydah governorate, officially known as the FSO Safer oil terminal. Like the thousands of tons of highly explosive ammonium nitrate that had been stuffed into a warehouse at the east end of the Mediterranean in 2013 and silently loomed as a threat against the Lebanese capital for more than six years, the estimated 1.15 million barrels of crude aboard the derelict Red Sea oil terminal, 7.5 kilometers offshore of Ras Issa, have been left unattended for more than five years. During that time, seawater has leaked into the vessel while highly combustible off-gases have likely built up in the holding chamber, risking explosion and an oil spill of historic proportions.

Should the vessel rupture and large amounts of oil spill into the sea, there would be wide-ranging and interrelated environmental, economic and humanitarian impacts. Immediately at risk would be the Red Sea’s 2,000-kilometer-long coral reef system, one of the most significant in the world and home to an estimated 1,100 fish species. This ecosystem feeds and provides livelihoods for hundreds of thousands of Yemenis, through fishing and related activities. In the event of an explosion and the crude catching fire, the westerly winds could expose millions inland to toxic fumes. An oil slick could also force the closure of Hudaydah and Saleef ports along Yemen’s western coast roughly 50 kilometers from where the FSO Safer is moored, with these ports serving as the entry point for most of the country’s commercial and humanitarian imports, representing a lifeline for millions of people. Meanwhile, the Bab al-Mandab Strait at the south end of the Red Sea is the gateway between the Indian Ocean and Europe and one of the busiest waterways in the world, meaning the impacts of an FSO Safer disaster would likely spread far beyond the region, given the potential disruption of global trade.

It is the enormous scale of what is at risk that has created such a valuable hostage for the armed Houthi movement. The hostage game is one the Houthis have refined during the ongoing conflict, having used the threat of denying aid agencies access to populations at risk of famine as leverage to silence those agencies while they pillaged vast sums of money and supplies from the relief effort. With the FSO Safer, well within range of Houthi artillery onshore, the group controls access to the vessel – control that repeatedly has allowed its leadership to rebuff United Nations’ efforts to carry out even a status assessment of the oil terminal. The seriousness of the threat, and the Houthis’ intentional delays in having the situation addressed, have raised it to the highest levels of policy making in the world, including discussions at the UN Security Council. This, however, has only reinforced the Houthi leadership’s belief that the oil terminal is a card they can leverage for concessions in other matters during any prospective negotiations regarding the wider armed conflict.

As recently as August, the group reneged on a commitment to allow UN inspectors onboard. In a subsequent media interview, Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, a senior figure in the group, explained that they had denied the inspectors access because the UN did not agree to a list of Houthi conditions. These included a demand that the inspectors should be accompanied by personnel and equipment to carry out any needed repairs there and then. In reality, the Houthis are paranoid that the outcome of the assessment has already been predetermined and will call for the removal of the oil from the terminal. For its part, the UN, while it agreed to carry out any light repairs that were immediately possible, could not agree to the Houthi conditions, given that major fixes to the vessel are likely necessary and the UN would need to know the type and extent of these repairs before it could even issue the tender to carry out the work.

Additionally, given the age of the FSO Safer – originally a single-hulled oil tanker built in 1976 and retrofitted for the Yemeni government in the mid-1980s to be a “Floating Storage and Offloading” terminal – and the length of time it has gone without maintenance, safely securing the crude onboard is likely impossible. What to do with the revenues from selling the oil were it removed, however, has also been a sticking point. The Houthis’ principal rival in the ongoing war, the internationally recognized Yemeni government, still officially owns the oil terminal and the crude in its bowels. Various estimates had pegged it at between US$50 million and US$80 million in value, which inspired bickering between the warring parties over what to do with the money and scuttled previous UN-led attempts to broker a deal regarding the oil terminal. However, time has almost certainly degraded the crude, which in concert with slumping global oil prices would mean its value today would be only a fraction of previous estimates.

Greed may have thus have receded as a factor, though it remains unshakably the case that neither of Yemen’s main warring parties act like they have the slightest responsibility for preventing the massive catastrophe that could befall their country and the region. In his interview, Al-Houthi summed up his zero-sum view of a potential disaster, noting that its impacts “would all cause more damage to them than to us.” The Yemeni government’s disregard for the wellbeing of the country’s citizens has been no less obscene, with its concern seeming to extend no farther than heaping blame on the Houthis for their handling of the situation. Indeed, a senior government official, speaking privately with the Sana’a Center, essentially framed the government’s position as: “if it explodes, it’s not our fault.”

The UN or other international stakeholders who might intervene must be careful not to feed the Houthis’ demands for greater concessions through raising the stakes. With the right imagination and balance of diplomacy and pressure there is, however, a possible horizon of de-escalation by allowing the lords of this war to use a resolution to the Safer situation as a demonstration of their goodwill toward Yemenis – even if in reality their motivations would be entirely self-serving. An agreement committing any revenues from the oil’s sale to the pandemic response is one potential creative compromise to explore. Short of this or a similar such arrangement, an apocalypse will remain in wait on the Red Sea.

Contents

- Hostage on the Red Sea

- The Struggle for the South Continues

-

Economic Developments

- In Focus: The Yemeni Rial’s Widening Exchange Rate Disparity Between Sana’a and Aden

- Economic Uncertainty in the South Complicates Govt-STC Standoff

- Yemeni Banks in Aden Face Increased Intimidation

- Fuel Standoff in Hudayah Eases

- Long-Running Ponzi Scheme Defrauds Hundreds of Thousands of Yemeni Investors

- Military and Security Developments

- On the Houthi Front

- Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

A bulldozer helps clear dried mud from a settlement for internally displaced people after flooding in Al-Noqaia’a, Al-Wadi district, Marib governorate, August 9, 2020. The rainy season this year was one of the most destructive in living memory. For more see ‘Deadly Flooding Wrecks Homes, Communities Across Yemen‘ // Sana’a Center photo by Ali Owaida

Developments in Yemen

Hostage on the Red Sea

Refocused Attention on Potential FSO Safer Oil Terminal Disaster

Focus on the threat of an environmental disaster related to the FSO Safer, the decrepit oil terminal offshore of Yemen’s west coast, increased for the United Nations and other stakeholders in Yemen in the first six months of 2020 and continued to sharpen through July and August. International attention was raised earlier in the year with United Nation Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2511 in February calling for UN officials to be given access to “inspect and maintain” the 45-year-old oil terminal which, with more than 1.1 million barrels of crude on board, has gone with almost no maintenance since 2015. Yemen’s armed Houthi movement, Ansar Allah, controls access to the FSO Safer – the terminal being within range of its artillery onshore – and it has repeatedly blocked UN attempts to inspect it.

In March, the governments of Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Yemen followed up with a joint letter to the UNSC calling for an “immediate solution” to prevent the “widespread environmental damage, a humanitarian disaster and the disruption of maritime commerce” that an explosion or spill would cause. This warning gained urgency in June following a report by The Associated Press that seawater had damaged ship pipelines and increased the risk of the vessel sinking. A diving team was dispatched in June by Safer, Yemen’s national oil company, to seal holes in the ship where seawater was leaking in, though it was unclear how long the patchwork solution would hold.[1]

On July 12, AFP reported that the Houthis had agreed to allow a UN assessment and repair team to access the tanker.[2] Three days later UNSC held its monthly meeting on Yemen with the sole topic of discussion being the FSO Safer. UN humanitarian affairs chief Mark Lowcock said the UN mission to the tanker would hopefully take place in the coming weeks. “We have, of course, been here before,” he noted, referring to August 2019 when the Houthi movement had made similar promises before canceling permission for the UN mission to board the vessel.[3]

Lowcock’s skepticism was warranted: the UN mission, planned for mid-August, was delayed due to the Houthi authorities refusing to issue the necessary approval. On August 17, Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, head of the Supreme Revolutionary Council, told Al Jazeera that the group had refused the UN inspection over suspicions that the assessment report would be politicized. He said the Houthi movement was insisting that a third party, possibly Sweden or Germany, send experts along with the UN team to ensure the results of inspection were independently verified, and that the necessary repairs be carried out simultaneously to the inspection.[4]

Concerned parties, including the Sana’a Center on multiple occasions, have warned of the potentially catastrophic consequences that an oil spill would risk to Yemen’s western coastline, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, as well as to other countries that border the vital waterway. The tanker holds more than 1.1 million barrels of oil. A limited-circulation international assessment seen by the Sana’a Center in September 2019 estimated that a spill at the FSO Safer terminal could be “potentially catastrophic … with ecological, economic and human health impacts all highly likely to occur on a large scale.” Specifically for Yemen, the report stated that within a week of a spill some 500,000 Yemenis could be affected, with food, fuel and water supplies compromised, the fishing industry crippled and pollutants spread down the coast; in the event of an explosion or fire, some 9 million Yemenis could be left breathing toxic fumes.[5]

The Heritage Festival in Yafa’a, Lahj Governorate, August 9, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Ahmed Shihab al-Qadi

The Struggle for the South Continues

The Yemeni government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC), in Saudi-brokered talks, agreed at the end of July to a new framework to jumpstart implementation of the Riyadh Agreement. As part of the new deal, the STC rescinded its declaration of self-rule across southern Yemen and the two sides agreed on the appointment of a new Aden governor and security chief. Progress on implementing further aspects of the agreement, however, later fell apart, with the STC suspending its participation in consultations with the Yemeni government in late August.

New Aden Governor and Security Chief Appointed

On July 29, the STC agreed to abandon its declaration of self-rule across southern Yemen and recommit to the Riyadh Agreement. Saudi Arabia has hosted delegations from the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the STC since late April for reconciliation talks aimed at ending renewed fighting between the two major Yemeni partners in the anti-Houthi coalition. As part of the announced breakthrough, a new governor and security chief for Aden were appointed, and the two sides agreed on the formation of a new cabinet, including STC participation, within 30 days.[6]

The updated framework was the latest attempt to implement the Riyadh Agreement, in which the Yemeni government and the STC agreed to unify politically and militarily under a Saudi umbrella. Signed in November 2019, the accord laid out a strict timetable for the formation of a new government that included STC participation; the return of the government to Aden; the appointment of new governors and security chiefs in southern governorates; the redeployment of forces and weaponry away from contested areas; and the absorption of STC-aligned forces into the ministries of defense and interior.

While the Riyadh Agreement managed to halt months of fighting, which saw Hadi’s government pushed out of the interim capital Aden in August 2019, the deal stalled over mistrust between the two sides and disagreement over the sequencing of implementation. The STC insisted that political aspects must come before security redeployments, while the Yemeni government argued the opposite. Tension between the sides escalated in April after the STC issued a decree declaring self-rule in the former South Yemen. Clashes reignited in May across frontlines in Abyan governorate between STC-aligned forces and troops loyal to President Hadi. In June, the STC seized control of the island governorate of Socotra, deposing the pro-Hadi governor. While the Saudi-led coalition announced a cease-fire on June 22 and deployed monitors to frontlines in Abyan, fighting has continued in the governorate.[7]

The revised framework agreed in July sought to resolve prior issues related to sequencing that torpedoed implementation of the agreement in the past by prioritizing political elements of the accord. As a first step, the Yemeni government and STC agreed on a new Aden governor and security chief. Ahmed Lamlas was named to the Aden governorship, while Brigadier General Mohammed al-Hamedi was appointed as security chief.

The background of the two men, most notably their home governorates, appears to have been a primary factor in securing an agreement on compromise candidates following months of stalemate. Neither Lamlas nor Al-Hamedi is native to Aden, and neither hail from the STC strongholds of Lahj and Al-Dhalea, or Abyan, the home governorate of President Hadi. These rival regions have had a longstanding identity conflict, which has manifested itself in several power struggles in Yemen’s modern history, including the 1986 South Yemen Civil War.[8]

By selecting candidates outside the Lahj-Al-Dhalea and Abyan rivalry, both the government and the STC were able to skirt a major driver of the current struggle over the south. According to Yemen government officials who spoke to the Sana’a Center, the STC presented three candidates for the Aden governorship position: one from Lahj, one from Al-Dhalea, and one from Shabwa. Hadi chose Lamlas, the former governor of Shabwa and current secretary-general of the STC, who was sworn in as Aden governor by the Yemeni president in Riyadh on August 11.[9] From the STC’s perspective, it was able to get one of its members appointed to the Aden governorship while simultaneously demonstrating that its secessionist project for South Yemen has appeal outside the confines of Lahj, Al-Dhalea and Aden. The Yemeni government, meanwhile, likely saw potential leverage in appointing a figure from Shabwa, which is under government control and has historic tribal and political ties with its neighbor Abyan to the west. Hadi’s hope, it appears, is that Lamlas’ Shabwani considerations will trump full loyalty to the STC and allow him to chart a middle course. Lamlas arrived at Aden airport on August 27, telling assembled reporters that his immediate priority would be rehabilitating infrastructure and improving service provision in the city.[10]

Al-Hamedi, the new Aden police chief, is from Hadramawt, where he held the post of security chief. Notably, Al-Hamedi gained esteem for his handling of Southern Movement protests, which began in 2007. There was little violence in Hadramawt during this period, contrasting with the crackdowns against demonstrations that took place in other southern governorates, where a number of demonstrators were killed by security forces.[11]

The appointment of Al-Hamedi also appeared aimed at partially satisfying Hadramawt’s demands for influence and bringing it back within the fold of larger political dynamics in the south. The Hadramawt Inclusive Conference (HIC), a gathering of Hadrami socio-political elite aimed at advocating for greater autonomy for Yemen’s largest governorate, had warned both the STC and Yemeni government against attempting to exclude Hadramawt and its considerations from the talks in Riyadh related to the future of the south. A delegation from the HIC and Hadramawt Tribal Alliance traveled to the Saudi capital on July 18 following an official invitation from Saudi Arabia to join the talks.[12] Both the government and STC have been courting influence in Hadramawt, with the latter organizing a rally in Mukalla on July 18 in support of southern secession.[13]

The STC, Citing Govt Intransigence, Pulls Out of Implementation Talks

Hopes for further progress were dashed on August 25 when the STC announced that it had suspended its participation in consultations with the GoY to implement the Riyadh Agreement. In a letter sent to the Saudi-led coalition, the STC cited a number of reasons for the suspension, including ongoing military escalations by government-backed forces, the failure to pay the salaries of public sector employees, the lack of measures to stem the depreciation of the Yemeni rial (see ‘The Yemeni Rial’s Widening Exchange Rate Disparity’) and the deterioration of public services in the south. The STC also accused the government of collaborating with Islamic State and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and incorporating members of the groups into its military formations in Abyan.[14]

On the Yemeni Government-STC Frontlines

Fighting abated between Yemeni government and STC forces in Shabwa and Abyan governorates in July and August, in part due to the presence of cease-fire monitors from the Saudi-led coalition. However, intermittent clashes did occur throughout the period, particularly on the frontline in Shoqra, east of Zinjibar, the capital city of Abyan.

Sporadic fighting also occurred from July 9 through July 21 in the vicinity of the Al-Anad military base, in Lahj governorate, one of the most important military bases in the country. The STC-aligned Al-Anad military axis, part of the 4th Military Zone, engaged in fighting involving heavy weapons with the 2nd Giants Brigade, aligned with President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi. Casualties were reported on both sides.

Fighting between pro-Hadi forces and separatist groups was not limited to official STC-aligned units, but also involved pro-secession tribal groups in Shabwa. The governorate has been under the full control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government since its military forces defeated STC-aligned forces in August 2019. Resentment among some groups remains, and fighting flared July 9 in Baaram area, Mayfa’a district, after security forces entered the village looking for a suspected drug smuggler. The security forces were attacked by members of the Al-Rashid tribe, many of whom were also members of the UAE-backed, pro-secession Shabwani Elite forces, which was essentially disbanded following the government’s consolidation of control in the governorate in August 2019. Three government soldiers were injured in the fighting, and five tribal fighters were detained. Government forces eventually withdrew from the area, and the fighters were released, as a result of tribal mediation.

The Yemeni Government’s Triangle of Power

Commentary by Ammar Al Aulaqi

The internationally recognized Yemeni government’s continued relevance on the ground, even after losing its interim capital of Aden last year, is largely due to its hold on the country’s oil and gas producing regions. These form what could be called the government’s triangle of power, drawn between the cities of Marib, Ataq and Sayoun in the governorates of Marib, Shabwa and Hadramawt, respectively, which account for all of Yemen’s oil and natural gas production. Control of Yemen’s oil and gas fields represents an immense strategic resource, both for their current revenues and future potential as hydrocarbon exports continue to recover.

Marib, Shabwa and Hadramawt, while rich in natural resources are also relatively sparsely populated, while the inverse dynamic is at play in areas held by the Yemeni government’s main rivals in the ongoing conflict: The armed Houthi movement and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) control the country’s most densely populated areas, which are also relatively devoid of easily exploitable natural resources. It should come as no surprise, then, the government has found its grip on these areas increasingly challenged by its rivals. Indeed, control of the Marib-Ataq-Sayoun oil-producing triangle not only has consequences for the progression of the current conflict, but could provide crucial leverage for warring parties attempting to shape their visions for a post-war Yemen.

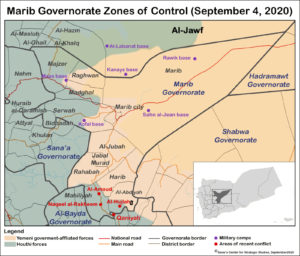

In January 2020, the Houthi movement launched an offensive and regained control of the strategic Nehm area. Located in Sana’a governorate, it is the meeting point of the Yemeni northern highlands and the desert of Marib governorate to the east. Several weeks later, the Houthi movement carried out another offensive further to the north in Al-Jawf governorate, capturing the governorate capital of Al-Hazm on February 29. These bold offensives represented a change in Houthi strategy from the previous five years of conflict, switching from a mainly defensive posture to go on the attack. By capturing Nehm and Al-Jawf, the Houthi forces positioned themselves to lay siege to Marib city and potentially seize the governorate’s oil and gas fields.

Should Marib city fall into the hands of the Houthis it would also put government-held Shabwa governorate and its oil fields in Bayhan and Uqlah under serious threat. This is why government brigades based in Shabwa, namely the Bayhan military axis, have been heavily involved in the battles to the west in Qaniah and Al-Abdiah fronts along the border between Marib and Houthi-held Al-Bayda governorate. While battles have been ongoing in this area since 2018, they have increased in frequency and intensity since April, when government troops advanced into Al-Bayda. It was a way of taking the battle to Al-Bayda before it came to Shabwa. By June, however, the Houthi movement was able to stem the government advance and a nascent tribal uprising, and push pro-government forces back into southern Marib.

Shabwa also came under threat from the STC following the breakdown in relations between the separatist group and the Yemeni government. After ejecting the government from the interim capital of Aden in August 2019, the STC did not hide its intentions to move on southern Yemen’s oil-producing regions. In a statement, STC head Aiderous al-Zubaidi identified oil-rich Bayhan in Shabwa and Sayoun in Hadramawt as areas that needed to be “liberated.” Forces aligned with the STC made a hasty advance toward Shabwa’s Ataq in the wake of the fall of Aden, but the offensive backfired, with the government counterattacking and expelling all STC-backed forces, including the Emirati-backed Shabwa Elite forces, from the governorate. This blow prevented the STC from securing Shabwa and moving on Hadramawt, which would have given the group and its Emirati backers de facto control of most of southern Yemen.

The Houthis and the STC have multiple motivations for wanting a piece of the government’s triangle of power. Among their chief concerns is that both groups control heavily populated regions of Yemen that lack substantial local revenue bases to support them. The majority of the country’s population and many of its poorest regions are in Houthi-held territory. The STC, meanwhile, controls the South’s densely populated governorates: Aden, Lahj and Al-Dhalea. The city of Aden in particular has long been a black hole when it comes to government spending, with public services a heavy financial burden on any ruling authority. These realities in Houthi- and STC-controlled territories differ greatly from the context in the Marib-Ataq-Sayoun triangle, which encompasses vast, sparsely populated areas rich in potential revenue from oil and gas.

The leadership of both the Houthis and the STC also see securing a piece of this triangle as crucial to achieving their respective greater ambitions, as well as a way of dealing the Yemeni government, a rival of both, a potentially decisive defeat. Along with the financial windfall of securing natural resource revenue, the Houthis are seeking to control all of pre-unification North Yemen to fulfill their grand political project, meaning Marib must come into the Houthi fold. For the STC’s vision of an independent southern state, it is essential that they control all of pre-unification South Yemen. Being cornered in Aden and its surroundings both undermines the economic viability of this project and denies the STC the legitimacy of being a truly pan-Southern actor.

Even after being expelled from its interim capital, Aden, the Yemeni government was still a player on the ground due to its control of the Marib-Ataq-Sayoun triangle. The government and its Saudi supporters are aware that losing any corner of this triangle would risk stripping Yemen’s ‘legitimate’ government of meaningful significance in the country, and they have thus fought with renewed fervor to hold these positions. After Houthi forces overran the government’s positions in Nehm and Al-Jawf, President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s government and the Saudi-led coalition shifted additional resources to defend Marib city. This led to a reshuffle in military command zones as well as the appointment of General Sagheer Bin Aziz, who is trusted by the Saudis, to lead all joint forces in Marib. Marib’s tribes, most importantly the Abidah and Murad, were also called into action to defend the governorate. These two tribes were also involved in the fierce defense of Marib city against a major Houthi offensive in 2015.

In Shabwa, the defeat of the 8,000 strong pro-STC Shabwani Elite forces reestablished the government’s almost full control of the governorate. Prior to the August 2019 fighting, control of Shabwa was divided between pro-Hadi forces and the UAE-backed Shabwani Elite. From Sayoun, the Hadi government fully controls Wadi Hadramawt and has an untapped reserve of manpower in the form of the First Military Region.

The recent battles in Shoqra, Abyan, between government and STC-aligned forces are also linked to the oil-producing triangle. Here, forces from the government-allied Ataq military axis and Shabwa special forces had advanced into Abyan, securing a buffer zone to protect the triangle behind them. For the Yemeni government, control of these oil-producing regions provides legitimacy on the ground and revenues to pay salaries and sustain loyalties. Whether against the Houthi movement or the STC, the Hadi government knows the Marib-Ataq-Sayoun triangle must be defended at all costs.

Ammar Al Aulaqi is a Yemeni engineer and public official. He is also a political and economic analyst, and served as a member of the advisory team to the Prime Minister in the Jeddah talks between the Yemeni government and the Southern Transitional Council in 2019. Al Aulaqi received a degree in environmental engineering from Dalhousie University in Canada and worked in the oil and gas industry before entering the public sector. He has contributed to many civil society initiatives in his native Shabwa governorate and throughout Yemen. He tweets @ammar82.

Other Political Developments in Brief

- July 14: The Houthi-run Supreme Political Council announced it had extended the term of council president Mehdi al-Mashat for one year, beginning August 24.[15]

- August 12: President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi left Saudi Arabia to head to the United States for medical treatment. Hadi has traveled to the world-leading Cleveland Clinic, a cardiovascular treatment center in the United States, five times in the last five years, most recently in June 2019.[16] Hadi returned to Riyadh on September 2.[17]

Economic Developments

In Focus: The Yemeni Rial’s Widening Exchange Rate Disparity Between Sana’a and Aden

Exchange rate divergence between Sana’a and Aden reached a record high by the end of August, with a Yemeni rial worth 33 percent less in Aden than in Sana’a. The rial was trading at YR805 per US$1 in the Aden parallel exchange market, compared to YR605 per US$1 in Sana’a.

The difference in value of the rial between government- and Houthi-controlled areas is a consequence of the split in the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) into rival institutions in Sana’a and Aden affiliated with the warring parties, leading to fractured monetary policy. The divergence started to widen following the Houthi authorities’ decision in December 2019 to ban the use in areas they control of newer rial banknotes issued by CBY-Aden.[18] In July and August, the rial depreciated around 7 percent in Aden relative to the Sana’a exchange rate, which has remained stable at around YR600 per US dollar since the beginning of the year.

Enforced Currency Stability in Houthi-Held Areas

The limited supply of old banknotes in Houthi-controlled territories compared to the large size of economic activity, along with the Houthi authorities adopting strict measures to enforce a fixed-exchange-rate system through the suspension of foreign-exchange trade in areas they control, have contributed to the stabilization of the rial’s value in northern Yemen.

For instance, during the past few months Houthi authorities have intensified restrictive measures banning the circulation of new banknotes in many frontline areas, including Ibb, Taiz and Al-Dhalea. This has helped spur new rial banknotes to increasingly flow toward areas nominally controlled by the Yemeni government. Meanwhile, CBY-Sana’a has both electronically and physically limited the transfer of dollars to areas outside Houthi control, according to a money exchanger based in one Houthi-held governorate.

Yemen Government’s Expansionary Monetary Policy and Hobbled Central Bank

In areas outside of Houthi control, the government’s general lack of revenues has led it to regularly print new banknotes in order to meet expenses, with this expansionary monetary policy being one of the key drivers of the Yemeni rial’s devaluation. By the end of 2019, the total rial liquidity in circulation in the country was estimated at YR3.4 trillion, meaning that CBY-Aden had printed YR1.7 trillion worth of new banknotes since its relocation decree in September 2016.[19]

As of the beginning of 2020, the Aden-based central bank had roughly YR200 billion held in reserve and has additionally printed around YR300 billion over the course of the year, according to a senior Yemeni banking official. Faced with a larger budget deficit this year resulting from the drastic decline in global crude prices and from government tax and custom revenues in southern areas being controlled by the STC, the Yemeni government has largely relied on the CBY’s overdraft financing instrument to cover government spending, including public sector wages, thus inflating the monetary base issued in new rial banknotes close to YR2 trillion. This has increased downward pressure on the rial’s value and helped drive inflation.

Additionally, over the last several months the CBY-Aden has faced a litany of pressures that have undermined its monetary role – most importantly the CBY’s mandate to protect the value of the rial – and accelerated the pace of rial depreciation. Again, one of the major factors hindering CBY-Aden is the ongoing struggle between the Yemeni government and the STC. Little progress has been witnessed in ending fragmentation and military clashes between the two parties, derailing efforts to lay the groundwork for new Saudi financial support to replenish CBY-Aden’s nearly depleted foreign reserves.

Since the beginning of 2020, the CBY-Aden’s monetary functions have been hindered by a lack of foreign currency stocks needed to finance imports. As of the end of August, the central bank had nearly exhausted the $2 billion Saudi deposit that was made available to it in early 2018. According to a credible source working in the Aden banking sector, the CBY’s remaining foreign currency holdings from the Saudi deposit stand at around $180 million, which is insufficient to cover a two-month bill of commodity imports.

The Aden central bank’s level of foreign currency intervention using the Saudi deposit has been limited of late. On August 13, it received approval from the Saudis to withdraw $61.5 million to cover requests for the import of basic commodities at the privileged exchange rate of YR650 per US$1. Between May and July this year, no withdrawals from the Saudi deposit were made.

Currency Traders’ Increased Fees and Speculation Related to Old-vs-New Banknotes

Yemen’s fractured monetary policy and dual rial banknote systems has negatively affected market sentiment and confidence in using the domestic currency in financial transfers across the country’s frontlines. In order to avoid the value fluctuations between new and old rials, exchange outlets and money transfer networks have taken to pricing their transfers in an intermediated foreign currency, generally the Saudi riyal or US dollar.

Financial service providers, including commercial banks, have reacted by charging 30 percent or more as a processing fee for cash transfers from areas held by the anti-Houthi coalition to Houthi-held areas. In other words, someone in a nominally government-held area has to send 1.33 units in newly printed rials for their intended recipient in a Houthi-held area to receive 1 monetary unit of old rial banknotes.

Indications from the currency market through July and August are that money exchangers and money transfer network operators have sought to profit from increased speculation on the differentiated exchange rates between old and new rial banknotes. As well, in southern Yemen, financial service providers appear to have been selling large quantities of their stocked newly printed rial banknotes to purchase foreign currency from the market, both to pay customers due transfers and to replenish their own foreign currency holdings.

Economic Uncertainty in the South Complicates Govt-STC Standoff

Underlying the standoff between the Yemeni government and STC over southern Yemen are economic considerations. If properly implemented, the Riyadh Agreement would help ease pressure that has mounted on the STC regarding the management of the local economy in Aden, delayed payments of allied fighters’ salaries, and the provision of basic services. These concerns helped shape the STC’s decision in April to announce self-administration across the south as it looked to draw the attention of Saudi Arabia and gain leverage during the mediation efforts that followed.

Amid start and stop progress on political and security aspects of the envisioned power-sharing arrangement, an agreement was reached in July to pay months of back salaries to STC-aligned forces. These groups were previously paid by the United Arab Emirates. Following the signing of the Riyadh Agreement in November 2019, Saudi Arabia assumed greater responsibility for the management of security in Aden and southern Yemen more broadly, including taking over salary payments for STC-allied forces following the withdrawal of most UAE forces from the country the previous month. However, with the breakdown of implementation talks between the Yemeni government and STC toward the end of August 2o20, no new salary payments were made.

The STC sought to use its security control on the ground in Aden to increase pressure for these payments to be made. In June, the group seized 60 billion newly-printed Yemeni rials (worth almost $80 million US dollars) and began diverting locally collected revenues to the National Bank of Yemen (NBY). STC anxiety over the outstanding salary payments for STC fighters, which had been accumulating since March, appeared to spike in July against the backdrop of the talks in Riyadh. On July 13, STC spokesperson Nizar Haitham issued a video message to the government, demanding it pay the outstanding salaries owed to STC-allied fighters since May or risk the STC taking matters into its own hands in order to pay these salaries, without specifying exactly what these actions might be. The demand for government intervention appeared somewhat wishful thinking, given the events that occurred over previous months and the STC’s desire to self-govern.

During the second half of July, the STC returned the newly-printed banknotes it had seized from the government and the Central Bank in Aden in June after an agreement was reached to pay back salaries. It was expected that some of the newly-printed Yemeni rial banknotes that the STC seized would be used to make such payments, though the outstanding salaries totaled 70 billion Yemeni rials, 10 million more than the seized banknotes.

Meanwhile, the undisclosed amount of newly-printed Yemeni banknotes seized by the UAE-backed Hadrami Elite Forces from Mukalla port at the end of June remains out of the government’s reach. After it was seized, the money was transferred to the local CBY branch in Mukalla, under the supervision of the Hadrami Elite Forces, whose commander, Faraj Bahsani, is also the governor of Hadramawt.

Yemeni Banks in Aden Face Increased Intimidation

Three separate incidents involving STC-affiliated fighters and Yemeni banks in July caused growing concern among the latter over the current operating environment in Aden.

The first incident saw STC-affiliated gunmen seize 750 million Yemeni rials belonging to the Cooperative and Agricultural Credit Bank (CAC Bank) in Aden on July 3. (Note: there are two separate executive branches of CAC Bank: one in Sana’a where CAC Bank was originally headquartered and one in Aden that was established in November 2018). The money was being sent from the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden to CAC Bank when it was intercepted at an STC checkpoint, despite the accompanying documentation specifying the details of the transfer. The money was then diverted to an STC-run military camp at Jabal Hadeed, before being returned to CAC Bank several days later following mediation between senior STC and CAC Bank officials.

The second incident concerned Yemen Kuwait Bank (YKB), in which an internal dispute quickly escalated following the direct intervention of Ahmed bin Briek, a member of the STC Presidential Council and head of STC Self-Administration Committee. Bin Briek ordered the deployment of gunmen outside the two YKB branches in the Sheikh Othman and Crater districts of Aden in response to appeals made by the YKB Crater branch manager, Lamya Magoor, who had objected to her planned reassignment by YKB senior management to a branch in Hadramawt. Meanwhile, both YKB and the Yemen Banks Association (YBA) issued separate letters denouncing the actions taken against YKB in Aden. Following direct communication between Ahmed bin Breik and senior YKB management over a two-week period, the issue was eventually resolved. YKB senior management scrapped the decision to reassign Magoor to Hadramawt, although she was still required to hand over the Crater branch to a new manager.

The third incident concerned the alleged deployment of gunmen operating under the command of Abdulnasser al-Bawa’a, more commonly referred to as Abu Hamam, at different Yemeni bank branches in Aden city in early July. The deployment led to the closure of a number of branches, including those belonging to Al Kuraimi Islamic Microfinance Bank and the Cooperative and Agricultural Credit Bank (CAC Bank).

Senior Yemeni bank officials who spoke to the Sana’a Center expressed their concern over the dangerous precedent that these disputes, specifically the deployment of gunmen at Yemeni bank branches in Aden in order to extract concessions, could set. There was a collective fear that other armed groups may look at developments involving YKB and seek to gain effective control over other Yemeni bank branches that fall within the armed groups’ respective areas of control.

Fuel Standoff in Hudayah Eases

The latest Hudaydah fuel standoff between the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the Houthis that spanned the entire month of June eased during July with the entry of eight different fuel shipments. The government suspended fuel imports to Hudaydah throughout June in response to the Houthis’ withdrawal of up t0 YR45 billion from a special account at the Central Bank of Yemen’s (CBY) Hudaydah branch intended to pay civil servant salaries.

At the start of July, the government agreed to lift the suspension and authorize the entry of the four shipments to Hudaydah in response to a request from UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths during meetings with government officials in Riyadh on June 30. The UN Special Envoy did not place any conditions on the Houthis for the receipt of these four shipments, which is surprising given the Houthis role in manipulating the fuel standoff for political and economic gain (For details, see the Sana’a Center’s Yemen Economic Bulletin: Another Stage-Managed Fuel Crisis). On July 2, the Technical Office of the Supreme Economic Committee awarded import licenses to four shipments carrying a total of 92,000 metric tons (MT) of fuel. Another four ships were granted permission later in the month, with just under 180,000 MT in total unloaded at Hudaydah port during the month of July.

Long-Running Ponzi Scheme Defrauds Hundreds of Thousands of Yemeni Investors

A massive fraud scheme was exposed in mid-July, leaving hundreds of thousands of Yemenis in the lurch for billions of rials in family assets and valuable jewelry. The Ponzi scheme, which paid profits to old shareholders from investments by new shareholders, began soon after the 2015 military intervention by the Saudi-led coalition and was based mainly in Sana’a. According to a video statement by Sultan al Sami’i, a member of the Houthi Supreme Political Council in Sana’a, one company, Al Sultana Palace, defrauded 350,000 investors. In total, 12 fraudulent companies were involved in the scheme. Houthi authorities arrested a number of individuals alleged to be involved in the con for performing illegal investment activities.

In July and August, hundreds of deceived investors held demonstrations in Sana’a. This included protests in front of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Presidential Office. According to media sources, the Public Prosecution in Sana’a demanded the payment of YR40 billion as a financial guarantee for releasing the arrested representatives working in Al Sultana Palace.

A Houthi supporter on the ‘Day of Wilayah’ event in Sana’a, August 8, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Military and Security Developments

Commander of Saudi-Led Coalition Forces in Yemen Dismissed for Alleged Corruption

Prince Fahd bin Turki, a lieutenant general and commander of the joint forces of the Saudi-led military coalition, was dismissed from his position on August 31. Bin Turki was sacked along with his son, Prince Abdulaziz Fahd bin Turki, deputy governor of Saudi’s Al-Jawf province, and a number of other officers and officials, over corruption allegations. A royal decree announcing the move stated that men were referred by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to the Saudi Control and Anti-Corruption Authority for investigation related to “suspicious financial dealings monitored at the Ministry of Defense”.[20] Lieutenant General Mutlaq bin Salim bin Mutlaq al-Azima, Deputy Chief of the General Staff, was appointed by Bin Salman to assume the duties of the coalition commander.

The firing of Bin Turki is a major shakeup in the Saudi-led coalition and represents the first instance that a major Saudi figure was implicated in corruption related to the war effort against the Houthis. According to more than half a dozen senior Yemeni government officials and political and tribal leaders who spoke with the Sana’a Center Bin Turki’s corrupt dealings were well known among the Yemeni leadership, including instances of diverting money, vehicles and material intended for coalition for his personal use.

Saudi scrutiny into corruption in the Yemen file appears to have increased in 2020 in response to Houthi military advances on the ground. In March, Houthi forces captured Al-Jawf governorate and have since set their sights on oil-rich Marib governorate. It is notable that Bin Turki’s son, Abdulaziz bin Turki, as deputy governor of Saudi’s Al-Jawf province, had previously been given some responsibility for coordinating among and paying tribes in Yemen’s Al-Jawf. The fact that local forces in Al-Jawf were perilously under-supplied, leading to their eventual collapse in the face of a Houthi offensive, may explain why the younger Bin Turki became the subject of corruption investigations. Two senior government officials also said that the Saudis were angered to discover that vehicles, weapons and equipment sent by Riyadh to Marib to aid in the defense of the governorate had not arrived to frontline areas.

Dynamics within the Saudi royal family may have also played a role in the decision to dismiss and investigate Bin Turki. He holds close familial ties to the late King Abdullah. Fahd bin Turki’s mother was King Abdullah’s sister-in-law. His wife is the daughter of the late king and sister to Prince Mutaib bin Abdullah. As head of the Saudi National Guard, Mutaib was considered a potential future contender for the throne during his father’s rule. After King Abdullah’s death in 2015, the former ruler’s close family was mostly sidelined by the new Saudi monarch, King Salman, with Mutaib the last senior member of the Shammar branch to retain his position.[21] Mutaib was later dismissed from his position and arrested in November 2017 as part of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s anti-corruption purge, which saw senior princes and Saudi businessmen locked in the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton. Many at the time saw the move as a crackdown by Bin Salman against potential rivals within the Kingdom.[22] A western diplomat based in Riyadh described Bin Turki’s dismissal as a “two-in-one” deal, in that targeting him was both to purge corruption and to settle an intra-Saudi royal dispute, within the context of further power consolidation by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Taiz Infighting: Pro-Islah Forces Put Down Challenges from Within Restive 35th

Infighting among government forces erupted in July in Taiz. The fighting was largely the result of long-simmering political and ideological disputes among military units and their associated political forces, and attempts by the Taiz military axis, affiliated with the Islah party, to enforce its control over southern Taiz governorate. At the core of the dispute is the 35th Armored Brigade, a government army unit that for years had largely been backed by the UAE. Based in Ash Shamayatayn district, the 35th Armored Brigade was led by General Adnan al-Hammadi from the beginning of the war in Yemen until he was killed by his brother in murky circumstances in December 2019. On July 10, his vacant position was finally filled by General Abdulrahman al-Shamsani, but the appointment was seen by rivals as an attempt by the Islah party to take over the 35th Armored Brigade.

On July 11, a convoy carrying Al-Shamsani was prevented from moving toward the 35th Armored Brigade’s base by soldiers from the brigade itself. The 35th is mainly dominated by Nasserist and leftist political forces, some of whom rejected their newly appointed boss due to the backing he received from the Islamist bloc.

Soldiers of the 35th Armored Brigade also clashed with members of the Islah-affiliated 4th Mountain Infantry Brigade, on July 18, in Ash Shamayatayn. The fighting took place after an anti-Islah protest, and resulted in the death of the son of a commander in the 35th Armored Brigade.

A separate commander in the 35th Armored Brigade, Marwan al-Bareh, also survived an assassination attempt in Ash Shamayatayn on July 24. That attempt led to fighting between members of the 35th Armored Brigade and the 4th Mountain Infantry Brigade, in which the latter shelled the former’s positions on Jabal Bayhan. The shelling led to the death of a civilian bus driver.

Islah, for its part, remains wary of ceding a foothold in Ash Shamayatayn, located on the main route between Taiz and Aden, to UAE-backed forces, including those loyal to Tariq Saleh, former President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s nephew who is currently based on the Red Sea Coast.

In August, the infighting spread to Taiz’s Jabal Habashy and Al-Ma’afer districts. From August 7 to 9, clashes took place in Jabal Habashy between forces backing the district security chief, Tawfiq Al-Waqar, and security forces including the Islah-affiliated Military Police and the 17th Infantry Brigade. The fighting ended with the latter’s takeover of Jabal Habashy, and Al-Waqar was forced into hiding.

Fighting between members of the 4th Mountain Infantry Brigade and the 35th Armored Brigade on August 21 in Al Nashma area, Al-Ma’afer district, led to the Taiz military axis deploying a large security force to the district. The security operation’s stated aim was to end the rebellion by members of the 35th Armored Brigade, and to reopen the main road between Taiz and Aden governorates in Al-Ma’afer, which had been closed as a result of the fighting. The day’s fighting ended with the complete takeover of Al-Nashma by the Taiz military axis forces, along with 35th Armored Brigade positions in Mount Bayhan, Ash Shamayatayn district, and Mount Rahish and Mount Al-Masha’ir, Al-Ma’afer district.

Witnesses reported that members of the 35th Armored Brigade fled to As-Sami’ district, east of Al-Ma’afer. Attacks were then carried out at night on August 21 by armed men on properties of those believed to be supportive of anti-Islah members of the 35th Armored Brigade, including one of the brigade’s commanders, General Abdul Hakeem al-Jabzi. Al-Jabzi’s son, Aseel, a dental student in Aden, was kidnapped and later found dead, with his body showing signs of torture.

The next day, the headquarters of the 35th Armored Brigade in Al-Ayn, Al-Mawasit district, was handed over to General Abdul Rahman al-Shamsani, who was finally able to enter having been previously prevented from doing so in early July.

Al-Mahra Tribesmen Clash with Saudi Forces

Saudi forces in Al-Mahra governorate clashed with local tribesmen in late August. The Saudis had tried to send forces to Shihn district, on the Yemeni border with Oman, but were prevented by the tribesmen on August 23. The Saudi forces made a second attempt to head to Shihn the next day, but were again stopped by local armed tribesmen, leading to clashes. No casualties were reported, but a Saudi vehicle was set on fire. Many local tribes in Al-Mahra have close links with neighboring Oman and are opposed to the Saudi military presence in their governorate.

Al-Qaeda and Islamic State Developments

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and Islamic State (IS) activity was recorded throughout July and August in Al-Bayda and Shabwa governorates. On July 23, a former Shabwani Elite soldier was killed in Mayfa’a district, eastern Shabwa, on the road between Al-Houta and Azzan. He was attacked by gunmen believed to belong to AQAP. The attack came a month after another former Shabwani Elite soldier was killed on the same stretch of road, which the soldier’s family blamed on AQAP. Shabwani Elite forces, until they essentially disbanded in 2019, had conducted operations against AQAP and it is now believed that the organization is carrying out revenge attacks.

On August 14, AQAP militants crucified and killed a local dentist in As-Sawma’ah district, southeastern Al-Bayda, after they had accused him of spying on the group for Yemeni government security forces. On August 25, gunmen belonging to AQAP blew up the medical clinic the dentist worked in, killing at least four civilians inside. Local security and government officials indicated that the other men killed had also been accused of spying. AQAP later released a statement confirming the cruxification of the dentist and claiming it had uncovered a spy network in Al-Bayda.[23]

On August 17, the Houthis claimed to have taken control of IS camps in Wald Rabi’ district, Al-Bayda governorate, after clashes with IS fighters. The Houthis then declared, on August 20, that they had killed the leader of IS in Yemen, Abu al-Waleed al-Adani, during an operation in Qayfah area, Rada’ district, Al-Bayda. The group later released video of an attack in Qayfah, which the Houthis claimed showed dead and captured IS fighters, as well as IS camps in the area.

On the Houthi Front

The Battle for Marib

August saw an intensified attempt by the Houthis to advance in Marib, where frontlines were relatively quiet in July. The Houthi push in and around Marib comes from three sides: from Al-Jawf governorate to the north; from Sana’a governorate to the west; and from Al-Bayda governorate to the south.

Houthi forces pressed forward on the Qaniyah frontline, in southern Marib’s Mahiliyah district. Their most significant advance was toward Naqeel al-Rakheem in early July. Naqeel al-Rakheem is one of the three main passes on the mountainous asphalt road between Marib and Al-Bayda, and overlooks Qaniyah and Al-Amoud, the center of Mahiliyah district. Houthi forces’ control of the pass means they are well-positioned to surround the neighboring government-held Al-Abdiyah district and isolate it from the rest of Marib governorate.

As July went on, the Houthis were able to press that advantage and advance in Al-Abdiyah. Houthi forces took the village of Al-Hujlah on July 28 and opened up a new frontline in the district, at the Kharfan mountains, but have made little progress there thus far. Fighting in both Al-Abdiyah and Mahiliyah involved heavy weapons and Saudi-led coalition airstrikes. The Houthis also sent tribal mediators to the Bani Abd tribe, in an effort to break up their alliance with the Yemeni government. The Bani Abd tribe has, however, refused the Houthi overtures.

The Houthis did advance throughout August in Mahiliyah district, gradually taking areas such as Al-Nahmah, Al-Samrah and Al-Arash in western Mahiliyah as the month progressed. On September 2 the Houthis entered Al-Amoud, the main town in Mahiliyah, and appear to be in control of the whole district, as they edge closer to Marib city itself.

The Houthis also gained ground in Al-Bayda during the period, seizing full control over two districts. On August 17, the Houthis reached a deal with local tribal leaders in Al-Zoub, allowing them to take control of the area and complete their takeover of Al-Quraishyah district, northwestern Al-Bayda. On the same day, the Houthis also took control of Wald Rabi’ district, northern Al-Bayda, after clashes with Yemeni government forces. In Al-Jawf governorate, a Saudi-led coalition airstrike killed at least 11 civilians on July 15, including children, according to the UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen, citing initial reports from the area. The airstrike took place in the village of Masafa, to the east of Al-Hazm, the capital of Jawf, in the southeast of the governorate. The Houthis took over Masafa and Al-Hazm in March 2019.

Another airstrike in the governorate on August 6 killed nine children and injured several other civilians from the same four families after three cars were hit. The attack took place in Naqeel Firadh, Khabb wa Ash Sha’af district, western Al-Jawf. A spokesman for the Saudi-led coalition said that they were investigating “the allegation of the occurrence of collateral damage”.

Fighting Continues in Hudaydah, Al-Dhalea, Lahj

Clashes took place throughout July and August in Hudaydah, becoming more heated as the summer wore on, particularly in Al-Durayhimi and Al-Tuhayta districts. Frontlines there, however, remained static. Each side has accused the other of violating the Stockholm Agreement, under which the Yemeni government and Houthi leaders agreed to a cease-fire in Hudaydah in December 2018.

In Al-Dhalea’s Qa’atabah district, Yemeni government and Southern Resistance forces advanced in multiple areas on the Al-Fakhir frontline against the Houthis. On July 14, anti-Houthi forces captured several positions, including Al-Badhaa, Tabat Al-Hawaa, and Tabat Qarha, in battles that led to the deaths of dozens of fighters on both sides. Anti-Houthi forces continued their advances on July 22, taking the villages of Al-Kharazah and Al-Qarhah, followed by Al-Soud on July 31. Anti-Houthi forces opened a new front in the direction of Al-Oud as a result of these advances, and appear to be seeking to link Al-Fakhir with another frontline, Murays, both of which are in northern Qa’atabah. Anti-Houthi forces continued their advances in Qa’atabah on August 22, taking the areas of Shaleel and Naasa after clashes that led to at least 20 casualties on both sides.

Anti-Houthi forces led by STC military units, also made significant advances in Lahj, in particular on the Hayd Lisoud frontline, in the north of Al Had district. Progress in Hayd Lisoud occurred throughout early July and STC forces had full control of the area by July 14. Heavy weapons, including tanks, were used in the fighting, as well as medium and light weaponry. Control of Hayd Lisoud is important because it leaves the STC in control of large areas of northern Al Had district, on the border with Al-Bayda.

The Houthis were able to advance on one front in Lahj. They took Al-Uqmi, a mountainous area in the governorate’s western Al-Qabbaytah district, on July 22, following intense clashes with Yemeni government forces. Al-Uqmi overlooks Al-Shurayjah area, which contains Yemeni government military positions.

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

Amid Lack of Hard Data, Expected COVID-19 Surge Not Shown by Indicators

Projections of a surge in COVID-19 cases in Yemen in July and August did not materialize, while anecdotal reports suggest the number of cases may have subsided in August.[24] However, there is no definitive data on the spread of the coronavirus in Yemen due to the low level of testing in the country and the refusal by the armed Houthi movement to disclose confirmed cases or deaths in territory it controls.

By September 1, 1,966 cases of COVID-19 and 571 deaths had been confirmed in areas of Yemen under the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government.[25] This figure likely reflects the lack of testing: Fewer than 7,000 COVID-19 tests had been carried out in Yemen by August 22, although this too is an undercount because the Houthis only report on negative test results.[26] More than 21,000 test kits have been supplied to Yemen, according to UNOCHA.[27]

UNOCHA reported that while confirmed case numbers slowed in August, indicators suggested the virus continued to spread.[28] Stigma, difficulty accessing treatment centers and perceived risks of seeking care were among the factors deterring people from seeking treatment, UNOCHA said.

There were indications that COVID-19 may have subsided in some parts of Yemen by the end of August. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) ended its emergency intervention in Aden at the end of August following consistently low patient admissions.[29] An unpublished assessment by an INGO in July, seen by the Sana’a Center, noted that fears around the pandemic had started to subside as Yemeni authorities increasingly denied or downplayed the continued severity of COVID-19. While the virus appeared to have subsided in major cities, there were concerns it may have started to rise in rural areas, the report said.

A staff member for an INGO engaged in the COVID-19 response in Yemen told the Sana’a Center that the lack of any systematic testing capacity had precluded evidence-based analysis of the spread of the virus. Reports of coronavirus from the ground had lessened in August, the INGO staff member said, but there were multiple possible reasons for this: As fear of the pandemic diminished among communities with the passage of time, people may have become less concerned by symptoms and less likely to report them. In many parts of Yemen, healthcare is inaccessible and people are unable to seek treatment, therefore cannot be identified. Fear of compulsory quarantine in isolation centers had made people afraid to be tested, the aid worker added. Finally, while coronavirus appeared to have subsided in some major cities, no assessment could be made about some remote parts of rural Yemen that are highly inaccessible, where residents may not even be aware of COVID-19 and so may confuse its symptoms with flu or other illnesses.

Ammar Derwish, a Yemeni doctor working in Aden, said most Yemenis had not stayed at home during the pandemic, and the early spread of the virus was brutal: “I personally know more than 20 people who died from suspected coronavirus, and I know people who know many others,” he told the Sana’a Center. Derwish suggested the lack of preventative measures, such as staying at home, may have increased the early spread of the virus but also the general level of immunity. This may suggest a second wave in Yemen would be less deadly than in countries that enforced strict lockdowns, he said. To what extent infection with COVID-19 may confer immunity is not yet clear.[30]

Derwish suggested that the comparatively less deadly outbreak in Yemen may be a result of the young average age of the country’s population, especially since COVID-19 is often deadlier amongst older patients. However, the dire state of the country’s health service, and the absence of the government coordination and support, leaves him lamenting that Yemenis were left to fend for themselves during a pandemic that still killed a large number of people.

“There is no state in Yemen,” Derwish said. “The people were left alone to deal with their fate. Yemenis are forced to face problems on their own, and the coronavirus pandemic was no exception. Some people tried to emerge and say they would do this and that, but the reality was, that they did nothing.”

Deadly Flooding Wrecks Homes, Communities Across Yemen

Torrential rain and wind starting late July, and lasting well into August, left at least 172 people dead and thousands displaced, with the hardest hit governorates being Abyan, Aden, Amran, Hajjah, Hudaydah, Lahj, Marib and Taiz.[31]

Monsoons come every summer to Yemen, with the season typically lasting from June to September, and are often thought of as a blessing by farmers and city-dwellers alike, providing valuable water for irrigation and respite from the summer heat. However, this year the rains brought a devastating amount of destruction in their wake. The UN estimates that 300,000 people have lost homes, crops, livestock or personal belongings in the past three months as a result of the rains and flooding. Particularly hard hit were internally displaced people (IDPs) who had already fled their homes because of the conflict and often were living in substandard conditions in camps. Many camps are in wadis, or dry river beds, which placed them directly in the path flood waters.

Hudaydah governorate, already one of Yemen’s poorest regions, was a focal point of the flooding. The Sana’a Center visited the governorate and, assisted by reports from local government officials, aid organizations and activists, compiled an assessment of the flooding: 118 communities in Hudaydah were affected in 10 districts. Flooding also destroyed four IDP camps. Excluding families in IDP camps, more than 11,250 families were forced to flee their homes, and over 7,400 homes were partially or completely destroyed. Four bridges were destroyed on the highway that runs between Hudaydah, through Hajjah governorate, to Jizan province in Saudi Arabia.

According to the Yemeni government’s IDP Camp Management Executive Unit in Marib, almost 17,000 IDP families had been affected by the flooding by August 5 in that governorate alone. Large numbers of IDPs were also left homeless in Abyan, Al-Dhalea, Hajjah and Hudaydah.

Following heavy rains this summer the Marib dam flooded, impacting many. Internally displaced Yemenis, originally from Tihama on the west coast, had found refuge near the dam at Al-Noqaia’a in Marib’s Al-Wadi district. Between August 5-9 photographer Ali Owaidan was there to capture the flood’s aftermath // All photos by Ali Owaidan for the Sana’a Center

“Many of the [IDPs] displaced by the floods were already living in abject poverty, often in overcrowded, makeshift shelters made from plastic sheeting or mud, which had been washed away or sustained significant damage,” said UNHCR spokesperson Andrej Mahecic on August 21. “People are now being forced to shelter in mosques, schools or with relatives, or live out in the open, in abandoned buildings — some of which are at risk of collapsing — or in whatever is left of their damaged homes.”[32]

Aside from the damage to IDP camps, the flooding also destroyed or damaged roads across Yemen, washed away agricultural land, led to hundreds of livestock drowning, caused electricity blackouts and destroyed cars. In addition, there were concerns landmines may have been washed away from known areas, presenting a danger to civilians.[33]

Yemen’s capital Sana’a witnessed severe flooding in the first week of August, overflowing the Sayilah, a road that turns into a water drainage system designed to take rainwater out of the city. Some of the city’s main thoroughfares, including Al-Zubayri Street, Al-Qasr Street and Tahrir Square, were left underwater.

Buildings destroyed due to recent floods in Al-Abhar neighborhood in Old Sana’a, August 12, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Sana’a’s Old City, a UNESCO World Heritage site, was significantly damaged. Houthi authorities said 111 houses had partially or completely collapsed as a result of the torrential rain. The distinctive mud brick houses of the Old City require constant upkeep, but many have been neglected as a result of the war, poverty, and a lack of adequate oversight from the authorities.[34] Among the collapsed houses was the home of one of Yemen’s most celebrated poets, the late Abdullah al-Baradouni. There had reportedly been plans to turn the house into a museum.

Other Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments in Brief

- July 12: An airstrike in Washhah district, Hajjah governorate, killed seven children and two women and injured four more, according to the UN.[35]

- July 15: Airstrikes east of Al-Hazm in Al-Jawf governorate killed at least 11 civilians, including children and women, and injured at least six more.[36] The UN Special Envoy for Yemen demanded a “thorough and transparent investigation” into the attack.[37]

- July 20: The Yemeni blogger and human rights activist Mohammed al-Bokari was sentenced to jail to be followed by deportation to Yemen by a Saudi court.[38] Saudi police arrested Al-Bokari in early April after he posted a video on social media in which he demanded equal rights for all, including gay people.[39] He has been denied legal counsel, experienced physical and psychological mistreatment and has been denied access to medication despite a chronic heart condition, Human Rights Watch reported. Al-Bokari fled Yemen in June 2019 after receiving death threats from Yemeni armed groups.

- July 23: For the first time since late 2018, the World Food Programme (WFP) has warned of the risk of famine in Yemen, should a lack of funding continue to impede its work.[40] WFP halved its food assistance to Houthi-controlled areas in early April. The food agency referred to a study of the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification that predicted high food insecurity would increase from 25 percent currently to 40 percent of the population by the end of 2020 in areas it examined, if humanitarian assistance is kept at current levels.[41] The analysis considers rising food insecurity in Yemen as the result of a combination of ongoing conflict, economic crisis, the outbreak of COVID-19 and natural hazards. In recent months, Yemen has been hit by floods and desert locusts.

- July 27: Reuters reported that the World Food Programme had succeeded in emptying the Red Sea Mills, which enabled the organization to distribute life-saving humanitarian aid supplies that had been inaccessible for two years due to ongoing hostilities. Stuck in between frontlines, the UN grain store had become inaccessible in September 2018 and damaged by shelling.[42]

- July 30: The Baha’i International Community (BIC) confirmed that the Houthi authorities in Sana’a had released six Baha’is, including Hamed Bin Haydara who had been detained in late 2013 and sentenced to death.[43] The Associated Press quoted bin Haydara’s wife, Alham, as saying they were flown to Ethiopia. Leaving Yemen was a condition of the men’s release, the AP reported, citing Houthi judicial officials who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to journalists.[44] In March, the Houthis’ supreme political council president, Mahdi Al-Mashat, ordered all Baha’i prisoners released and Bin Haydara’s death sentence lifted. However, at an August 22 court hearing the Houthi prosecutors said they had not dropped charges against the Baha’is and considered those who had been released “fugitives”. According to BIC, the prosecution had asked bailors to ensure five of the released Baha’is attended a hearing on September 12.[45]

- August 2: Some 131 Malaysians, mostly students according to the Malay government, stranded in Yemen since March following the outbreak of COVID-19, returned to their home country, arriving in Kuala Lumpur via a special repatriation flight operated by Egypt Air. Seventeen others were expected to arrive the following day via an Emirates commercial flight.[46] Twelve of the group tested positive for COVID-19 on arrival in Malaysia.[47]

- August 8: An airstrike hit homes and cars in Al-Jawf governorate killing 20 people, including seven children, Save the Children said, citing local health authorities.[48] The UN partners reported that nine children were killed and seven injured.[49] Special Envoy Martin Griffiths condemned the airstrike.[50]

- August 13: Human Rights Watch reported that Houthi forces had forcibly expelled thousands of Ethiopian migrants from an unofficial settlement in Sa’ada governorate to the Saudi border region in mid-April, accusing them of spreading COVID-19 inside Yemen. Tens were killed by both Houthi forces and Saudi border guards, with those surviving fleeing to a mountainous border area. While many are thought to remain stranded in the border region without safe access to food and water, hundreds have been allowed to enter Saudi Arabia before being arbitrarily detained in unsanitary facilities with no access to legal counsel while they await deportation to Ethiopia.[51]

- August 20: Six major international NGOs with operations in Yemen called on USAID to end its partial suspension of humanitarian aid to Houthi-controlled northern Yemen.[52] Since March 28, USAID has partially halted funding to NGOs in Yemen’s north in response to Houthi interference in aid distribution.[53] The suspension was initially expected to last until the end of June, but has been extended since.[54]

- August 21: Ethiopia’s foreign ministry spokesperson Dina Mufti said the country was working to repatriate 1,200 nationals stranded in Yemen.[55]

International Developments

In the Region

A man buys Saudi riyals at Al-Hamdi Exchange on Haddah street in Sana’a on August 14, 2020. // Photo by Asem Alposi

In Focus: Yemenis in Saudi Arabia Have Less Money to Send Home, More Pressure to Leave

Yemeni workers in Saudi Arabia are used to making trade-offs to save money and send the remittances that support their families in Yemen and prop up their country’s underdeveloped economy. But in interviews from Riyadh, Jeddah, Taif and Dammam during the kingdom’s coronavirus crisis, Yemeni migrants discussed the pressures piling up in recent years and months. They spoke about the struggle to pay the rising costs of permits and expenses, the elimination of available jobs under Saudization policies, about dodging crackdowns on foreign workers that sometimes sweep up legal residents along with those residing in the country illegally and, most recently, about worries that COVID-19 measures and fallout will put them out of work and leave their families back home without financial support. With remittances a key external factor mitigating economic collapse, the subject is an essential consideration in Yemeni relations with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Arab countries that host large numbers of Yemeni expat laborers.

Read the full report by Sana’a Center researcher Ali Al-Dailami here.

Regional Developments in Brief

- July 18: The emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah, was admitted to hospital for medical checks. A royal order was issued to temporarily transfer some of the 91-year-old emir’s constitutional prerogatives to Crown Prince Sheikh Nawaf al-Ahmed al-Sabah.[56]

- July 20: King Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud, 84, was admitted to hospital in Riyadh for an operation to remove his gallbladder. The Saudi monarch was discharged after the procedure on July 31, the Saudi royal court said.[57]

- August 4: Former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad wrote to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman urging Saudi Arabia to find a peaceful route to end the war in Yemen, The Times reported.[58] Copies of the letter were also sent to the Iranian Foreign Ministry, Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi and UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. The new initiative on Yemen has propelled Ahmadinejad, who said he wrote the letter as a private citizen, back into the Iranian public sphere.

- August 13: The UAE and Israel, in a statement released via Twitter by US President Donald Trump, officially normalized relations between the two countries. The announcement, made the UAE the third Arab country to normalize relations with Israel, following the establishment of full diplomatic relations between Egypt and Israel in 1980, and between Jordan and Israel in 1994.[59]

- August 18: The Sultan of Oman announced a major government restructuring in a series of royal decrees. Several new ministries were created while the foreign affairs and financial portfolios were removed from the sultan’s direct supervision. Oman’s longtime foreign minister, Yusuf bin Alawi, was replaced by Badr bin Hamad al-Busaidi. Bin Alawi had served as the country’s top diplomat since 1997, playing a key role facilitating talks between the Houthi movement and Saudi Arabia aimed at deescalating the conflict in Yemen.[60]

In the United States

Democratic Party Pledges to Pull US Support from Saudi-led Coalition in Yemen

The Democratic Party pledged to stop US support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen and help end the conflict in its 2020 platform approved during the Democratic National Convention on August 18.[61] The platform outlines party policy on a wide range of local and domestic issues, although it is not binding.

Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, who served two terms as vice president to former US President Barack Obama, pledged in May 2019 to end US support for the Arab coalition in Yemen in what was his campaign’s first major foreign policy announcement.[62] The move followed President Donald Trump’s veto of a congressional measure broadly supported by Democrats that would have cut US military support for the coalition in Yemen by invoking the War Powers Act, which prevents presidents from indefinitely placing troops in war zones without congressional approval. Militarily, the US provides logistical support, coordinates on intelligence and facilitates arms sales to Saudi Arabia.[63]

The Democratic party’s 2020 platform reveals a shift in tone regarding its Gulf Arab allies and Iran since the party’s previous 2016 platform, which did not mention Yemen. The Democrats in 2016 affirmed their support to US “Gulf partners”, pledging to “bolster their capabilities” in countering Iran, Hamas and Hezbollah,[64] while the 2020 platform called for a reset of America’s relationship with its Gulf partners to better reflect US interests and values. The Democrats said they would suspend the Trump’s administration “blank check era” to the Gulf monarchs and involvement in the region’s internal rivalries and proxy wars.[65] The stark change in the Democrat’s language toward Gulf countries signals a further partisan divide on the issue of US allies and policy in the Middle East.

Trump formally accepted his renomination as the Republican party’s nominee on August 27. The Republican party decided not to publish a party platform for 2020.[66]

Senate and House Try Again to Limit US Assistance to the Coalition

For the fourth year in a row, US legislators in both chambers of Congress have introduced amendments into their versions of a key defense policy bill aiming to enforce some oversight, transparency and restraint on US military involvement in the Yemen War and on American support to the Saudi-led coalition.

The US Senate and the House of Representatives each produce their own versions of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which lays out defense budget priorities for fiscal year 2021. A reconciled version forged in a conference committee ultimately is sent to the president for approval or veto.