Introduction

Once a small-scale intervention in a forgotten crisis, the humanitarian response in Yemen has grown in the past decade into one of the biggest, highest-profile and costliest responses in the world. In its attempt to address what is often described as the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, the United Nations’ 2020 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) for Yemen targeted 15.6 million people for assistance prior to the outbreak of COVID-19; in 2021, 20.7 million people are considered in need of some form of humanitarian assistance, with aid efforts targeting 16 million of them.[1]

This portrayal of Yemen as the worst and biggest crisis, one in which famine is always imminent, disease is always deadliest and the risks and obstacles on the ground are unparalleled, is by now a well-set narrative. Yet those who have worked in the Yemen humanitarian response often question this public face of the crisis and whether it only serves to sustain a deeply flawed response. Many of these aid workers, including several with experience in other responses, are conflicted about whether data and numbers generated in the Yemen context and claims made based on them are truthful or merely a story propagated to ensure a continued source of funding and to excuse the failure to deliver the quality and type of response most needed.

While subsequent reports in this series will delve into the main challenges of the Yemen humanitarian response, operating modalities and its management from the highest levels, this report sketches in the foundations of the current response. It also questions the dominant narrative to explore whether Yemen really is the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. “Worst” is subjective, but key humanitarian data sets — whether in terms of health, nutrition, need, casualties or costs — often provide bases for the claims made. For this report, the data sets used to guide the Yemen response are compared to those from other major humanitarian crises, namely Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan and Syria.[2] The results show a more complex picture than what donors and the public have been asked to accept at face value, and call into question the effectiveness of the response.

The Yemen conflict in 2021 encompasses a mosaic of multifaceted local, regional and international power struggles that are the legacy of recent and long-past events. In recent years, frontlines have largely been static: the armed Houthi movement controls most of northern and central Yemen, including main population centers and accounting for approximately 75 percent[3] of Yemen’s population, while the southern and eastern parts of the country – comprising vast swathes of lesser-populated territories – remain largely under the nominal control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government. While a military victory remains elusive, the outlook for a political solution is also bleak; peace talks have so far failed and fighting recently escalated in Marib governorate. The Stockholm Agreement, backed by the UN and signed by the warring parties in December 2018, remains largely unimplemented, and a newer initiative under the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen (OSESGY) also has stalled. New impetus is sorely needed not only to end the war, but also to respond to its consequences on the civilian population.

The Pre-War Focus on Development

Even before the current war, Yemen was the poorest country in the Middle East, ranking 154 out of 187 in the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index.[4] Development has been constrained by regular outbreaks of conflict and political instability; deeply embedded corruption leading to weak state institutions and a lack of infrastructure; limited education opportunities; and a political elite focused on the consolidation of power and wealth and resistant to reform. Western counter-terrorism concerns led to a focus on security assistance, which the elites used to shore up their continued control. Since the 1990s, an over-dependence on oil exports has stifled growth and investment across other economic sectors.[5] With a mandate to improve long-term development indicators, a development conglomerate of UN agencies and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) – including UNDP, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), among others – was present and working in Yemen well before the current war, and had built longstanding contacts with authorities and civil society.

The first consolidated humanitarian response in Yemen – the 2010 HRP – was established following the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people due to a series of six conflicts between the Yemeni army and Houthi forces in Sa’ada governorate between 2004 and 2010.[6] The popular uprising in Yemen in 2011 and the ensuing clashes in Sana’a and other northern governorates, as well as the resurgence of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), led to additional population displacements and triggered further humanitarian interventions.

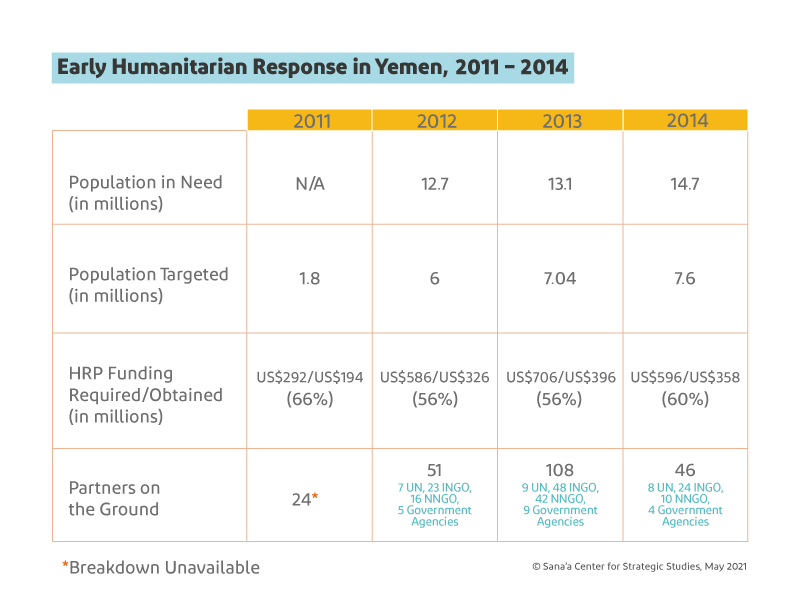

Initially, the humanitarian response focused on early recovery, an approach involving the meeting of emergency needs in ways that can quickly return to supporting longer-term development needs. This response – and the funding it required – swiftly scaled up (see Table 1.1). In July 2011, 24 organizations were involved in the HRP; a year later, this had grown to 51,[7] and by the end of 2013, it had more than doubled again to 108.[8] The financial ask also increased, from US$187 million for the response in 2010[9] to US$596 million by the end of 2014.[10] As far back as 2012, more than 10 million people were believed to be food insecure, with close to 1 million children under 5 severely malnourished and 13 million people estimated to require water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) support.[11]

Table 1.1

Sources: UNOCHA Humanitarian Response Plans, Consolidated Appeals, Financial Tracking Service

Sources: UNOCHA Humanitarian Response Plans, Consolidated Appeals, Financial Tracking Service

HRPs formulated between 2010 and 2014 clearly indicated the need for a humanitarian response to acute as well as chronic needs, with the deterioration in the political and security context significantly impacting the 2015 response and nearly tripling funding requirements for that year.[12] However, interviews with key informants from early years of the response indicate that the profile of staff in Yemen during this period remained largely development-oriented, with a longer-term approach to the implementation of activities and programs. Their focus leaned heavily on early recovery, improving development indicators and investment in local institutions despite a sudden spike in humanitarian needs, which require a different response and skillset than development.[13]

War, Evacuation and Resetting Assistance for the Crisis

The events of late 2014 and early 2015 dramatically changed the humanitarian outlook in Yemen. The armed Houthi movement, capitalizing on growing instability, took over Sana’a in September 2014 after forming an alliance with ex-President Ali Abdullah Saleh and his loyalists in the General People’s Congress party (GPC). Attempts to establish a technocratic government failed, and by January 2015, President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and others were placed under house arrest by armed Houthi forces. Parliament, the constitutional court and other state institutions were suspended. In March 2015, after an initial escape to Aden, Hadi fled Yemen as Houthi forces expanded their push and took over parts of the southern port city. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) led a regional military coalition to support Hadi’s government and began an air campaign on Houthi-controlled areas in March 2015, followed by a ground operation. The coalition recaptured Aden in August 2015, and the city was declared the interim capital of Yemen.

Reacting to the quickly deteriorating political and security context, initial cadres of humanitarian staff and most of the diplomatic community evacuated Yemen in February 2015. Following the start of the air campaign in March 2015, most of the remaining members of the international humanitarian community and diplomatic corps evacuated the country; humanitarian base offices were re-established in Amman, Jordan, and embassy relocations were split between Amman and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. In the following weeks, any ongoing humanitarian activities were carried out by remaining Yemeni staff, overseen through remote management. The only exceptions to this were Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which have remained in Yemen with an international presence throughout the conflict, including in key areas such as Sa’ada.

Shortly after the evacuation of international staff, reports filtered out that the humanitarian consequences of the air campaign were severe, and that the humanitarian situation was rapidly deteriorating. Six weeks after the evacuation, a small core group of UN staff returned to Sana’a to try to address Yemen’s exponentially increasing needs.[14]

The choice of Sana’a was obvious: it was the capital; country offices and most senior Yemeni staff were there, as were institutions that had long been interlocutors and partners; it boasted proximity to the population most affected by the escalation in the conflict; and there was a more volatile security context in Aden and the south. This assessment accompanied a belief that the conflict would not last long and there would be a quick return to the status quo. However, given that the armed Houthi movement had established de facto control over state institutions in Sana’a, the decision to return to Sana’a as the humanitarian capital was a pivotal moment that has had long-term strategic implications for the humanitarian response in Yemen. Unlike any other response in the world, all country offices and representation of the most senior humanitarian leadership in Yemen sit outside territory controlled by a recognized government. This has had serious consequences for the ability to negotiate and wield leverage with the armed Houthi movement with regard to aid implementation or the establishment of independent humanitarian action. To an extent, it has legitimized an armed political-military movement that has consolidated control over a large part of the population of Yemen. Given this, it may have been preferable to have limited senior staff presence in Sana’a in favor of a more diffuse spread, and to have factored in contingencies early on in the response.

Further, the initial core team that re-entered Sana’a prioritized UN leadership and security staff over INGO staff, who were and remain the main implementers of the humanitarian response in Yemen.[15] While the importance of reintroducing leadership and security functions into the country is clear, the choice to not prioritize key operational staff was questionable. The goal of any humanitarian response is the provision of aid. Swiftly involving only security personnel resulted in the UN Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS) guiding humanitarian operations rather than allowing programming objectives to determine the necessary security support.[16] This overweighting of security versus programming needs in 2015 quickly became a serious constraint on operations and has shaped the response to date.[17] This issue will be examined in more depth later in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Security’.

At the start of 2015, the HRP estimated that 15.9 million people were in need of some form of humanitarian assistance in Yemen. In April 2015, the humanitarian community launched a flash appeal for US$273.7 million to reach 7.5 million people affected by the conflict over a period of three months.[18] At the time, it was estimated that 300,000 people had been displaced across 19 governorates, while more than 1,200 civilians had been killed and 5,000 injured.[19] By June 2015, a revised HRP estimated that, due to the conflict, 21.1 million people were in need across the

country and 11.7 million people were to be targeted to receive humanitarian assistance, requiring funding of US$1.6 billion.[20] Struggling to regain a foothold and respond to needs within the new context, it quickly became clear that the capacity in place in Yemen was not equipped to handle the evolving needs. Due to this, on July 1, 2015, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC)[21] declared Yemen a systemwide Level 3 (L3) emergency. At the time, it was one of six L3 emergencies globally.[22] Although the IASC no longer considers Yemen a systemwide L3, the largest humanitarian agencies, including WFP and UNICEF, continue to designate it as such internally to ensure they are able to allocate requisite resources.[23]

Emerging Gaps: Response System Struggles to Keep Pace with Rising Global Need

The rapid growth of the response in Yemen reflects global trends of a massive expansion in humanitarian needs and humanitarian funding in recent decades. Still, despite the increase globally in the humanitarian system’s resources and institutional machinery, its operational capacity is worsening and gaps in coverage are increasing. This can be linked to the foundations of the system remaining largely unchanged while realities on the ground no longer correspond to the early years of organized humanitarian interventions.

Though the Biafra conflict (1967-1970) is often referred to as the starting point for modern-day humanitarianism, international efforts to relieve suffering go back much further. Examples of this include the American Indian (Choctaw Nation) support to the Irish during the potato famine in the 1840s, efforts by religious organizations to alleviate suffering, and the creation in 1863 of what is now the ICRC. The first recorded global aid relief effort was in response to the Great Northern Chinese Famine of 1876-79, which killed nearly 10 million people in rural China. At that time, funds equating to between US$7 million and US$10 million were raised to support a relief effort. After World War II, the UN and its agencies were created and the fourth Geneva Convention to protect civilians in times of war was adopted. As a result, humanitarian efforts became more organized. The structures that have formed the basis of the humanitarian aid world have stayed largely unchanged since then.[24]

The essence of the system, the main underlying premise of “humanitarian aid,” since its inception has been: to address humanitarian need when and where it arises, with a focus on addressing the needs of civilians caught up in conflict and natural disasters; to ensure protection of civilians within conflicts; and to address the consequences of displacement. Despite this well-accepted foundation, there is no single definition for “humanitarianism” or “humanitarian response.” For the purposes of this series of reports, “humanitarian action” is defined through the principles endorsed by key donor nations in Stockholm in 2003, as support provided to people affected by conflict and natural disasters to “save lives, alleviate suffering and maintain human dignity” during a crisis.[25] It is guided by the four commonly accepted and recognized principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence.[26]

While the foundations have not changed, the system itself has experienced exponential growth over time. This has led to a (sometimes painful) process of institutionalization and bureaucratization as well as attempts at professionalization, giving the humanitarian sector the face that is familiar today – fronted by loosely interconnected structures of the UN, (I)NGOs and other aid organizations such as MSF and the Red Cross/Red Crescent movement.[27]

Humanitarian response data over the past quarter of a century[28] reveals a huge increase in indicators across the board (people in need, funding, operations, field staff, etc.). A full analysis of the reasons for this increase is outside the scope of this report, but contributing factors may include: that conflict and natural disasters increasingly affect highly populated areas creating greater need; the steep increase in the world’s population; and a rise in protracted emergencies with long-term challenges created by instability and mass displacement that cannot be managed through short-term interventions.[29]

In 2000, it was estimated that approximately 35 million people were in need of emergency humanitarian assistance.[30] By 2020, this had risen to 167.6 million,[31] an almost fivefold increase in identified people in need in two decades. In parallel, the humanitarian aid sector has also expanded rapidly. In 2000, the required humanitarian funding for all coordinated appeals was US$1.91 billion (worth roughly US$2.92 billion in today’s US$),[32] which covered consolidated appeals for 14 response plans[33] and provided jobs for approximately 210,000 field workers.[34] By early 2020, required humanitarian funding (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) reached US$28.8 billion for 37 response plans[35] with more than 570,000 field workers employed in the sector.[36]

Table 1.2

Source: UNOCHA Financial Tracker Service Appeals and Response Plans overview per year, US Committee for Refugees, Development Initiatives, UNOCHA reports.[37]

Source: UNOCHA Financial Tracker Service Appeals and Response Plans overview per year, US Committee for Refugees, Development Initiatives, UNOCHA reports.[37]

The figures in Table 1.2 show disproportionate growth between indicators from 2000 to 2019. While the target population for humanitarian response has nearly tripled over the past 20 years, funding requested has grown well more than tenfold.[38] In 2019, despite a decrease in the number of people targeted for assistance to 93.6 million, down from 106 million in 2010, there was no corresponding drop in requested funds. In short, the costs of the sector are rising much faster than the number of people being reached. A former head of the World Food Programme (WFP) noted with concern that from 2002 to 2016, three to four times the financial resources were required to provide global food assistance to roughly the same caseload.[39] Such illustrations call into question the efficacy of the aid sector as a whole.

The Yemen Response in Numbers

Figure 1.1

Source: UNOCHA, End of Year Report HRP Yemen 2019

Source: UNOCHA, End of Year Report HRP Yemen 2019

The humanitarian crisis in Yemen has often been described as the worst in the world, and, since 2018, it has been portrayed as the largest humanitarian response. Examining key emergency indicators from Yemen alongside those from L3 humanitarian responses in other countries offers insight into the accuracy of these claims. Comparisons show that when looking at absolute numbers, it is true that Yemen has an extremely high number of people affected by the conflict. But, when looking at relative numbers, other countries show larger segments of their populations affected by crises, indicating more broadly based high levels of hardship and suffering.

To put the prevailing narratives, including the idea that the response is underfunded, into perspective, the rest of this report undertakes a comparison of the Yemen crisis and response with other responses based on the publicly reported data. Four comparative countries have been chosen to ensure a consistent picture: Syria, Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and South Sudan. All of these responses were designated systemwide L3 emergencies at some stage and most function as corporate emergencies.[40] All four countries are designated complex and protracted conflict emergencies, like Yemen.

The Largest Humanitarian Crisis and Response

In terms of the number of people in need and targeted for humanitarian support, the Yemen crisis and the response are, indeed, the largest in the world. Questions surrounding the reliability of data in Yemen and how need is defined will be addressed later in this series of reports, in ‘The Myth of Data in Yemen‘. However, according to the Yemen HNOs of 2020 and 2021, 24 million people in Yemen need some form of humanitarian assistance, approximately 80 percent of the population. Even after the 2021 figures were revised, to 20.7 million people in need and 16 million targeted, Yemen’s absolute numbers remained highest (see Table 1.3).[41] Prior to the spread of COVID-19, the Yemen HRP for 2020 targeted 15.6 million people, just over half the population.[42] South Sudan and Syria, however, reported higher proportions of people in need by the end of 2020, at 74 and 77 percent, respectively (see Table 1.3), with the relative scale appearing to indicate worse situations in terms of broad-based needs prevailing across the countries.

Table 1.3

Source: UNOCHA, country-specific HRPs 2021, UNData[43]

Source: UNOCHA, country-specific HRPs 2021, UNData[43]

Yemen also tops the list in terms of the scale of the humanitarian response, reporting the most people targeted, even though the humanitarian responses in both South Sudan and Syria aim to reach a higher percentage of those populations.

The Second Most-Expensive Response in the World

Compared to the annual funding requested from donors, almost all global responses, including the Yemen response, are characterized as underfunded. However, funding appeals are rarely met fully, and an interesting picture emerges when funding allocated to Yemen is compared to elsewhere in the world. The Yemen humanitarian response has attracted almost US$17 billion since 2015, with funding generally increasing and a huge influx in 2018 and 2019. Funding allocated to Yemen did decrease heavily and below initial funding levels in early 2020 as a result of cuts by the United States over access constraints and a drop in funding from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the United Kingdom. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic also constrained funding for all emergencies. Yet despite this, the Yemen response maintained a significant amount of funding in 2020, US$2.2 billion (see Figure 1.2), remaining the second most-funded response globally, behind Syria.[44]

Figure 1.2

Source: UNOCHA Financial Tracking Service, updated through December 2020

Source: UNOCHA Financial Tracking Service, updated through December 2020

Putting it in a global perspective, between 2015 and 2019,[45] US$70 billion has been allocated to consolidated response plans and appeals worldwide. During that time, the Yemen HRP was allocated US$9.8 billion, 14 percent of the global total. Furthermore, an overwhelming portion of global funding has been dedicated to the Yemen and Syria responses. Taken together, Yemen and Syria accounted for 27 percent of global funding for consolidated response plans and appeals between 2015 and 2019. The other 73 percent of funding was split among approximately 33 other responses.

Figure 1.3

Source: UNOCHA Financial Tracking Service

A detailed analysis of cost and expense is outside the scope of this report, but the expensive nature of the Yemen response merits further investigation and analysis, in particular given the effectiveness of the response. How this high funding level, and the desire to retain it, impacts the investment in maintaining questionable narratives about the Yemen response will be discussed further in ‘The Myth of Data in Yemen’.

Defining the Worst: An Analysis of Four Indicators of Human Suffering

While Yemen reports the highest number of people in need globally, whether it is therefore the worst crisis in the world demands a more nuanced analysis. To explore this, the following key indicators will be compared: number of civilians killed, displacement, food security and nutrition, and health.

Number of Civilians Killed

The number of civilians killed and injured is a key indicator of the severity of a conflict. From June 1, 2015, to October 31, 2019, it is estimated that more than 12,000 civilians were killed in Yemen in direct attacks as a result of the conflict.[46] While any civilian death is a devastating loss and the conflict-related death toll in Yemen is considerable, available data suggests other conflicts in the world are more deadly for the civilian population.

Figure 1.4

Sources: Yemen,[47] Syria,[48] Afghanistan,[49] DRC,[50] South Sudan[51]

Sources: Yemen,[47] Syria,[48] Afghanistan,[49] DRC,[50] South Sudan[51]

Direct conflict-related deaths do not necessarily offer a full picture of a war’s death toll. As such, indirect deaths related to the conflict are often taken into account when and where possible. An analysis by UNDP and the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures estimated that by the end of 2019, 233,000 deaths in Yemen would be attributable to both conflict and humanitarian-related causes, including 131,000 deaths from indirect causes such as lack of access to food, health services and infrastructure.[52] In comparison, South Sudan experienced an estimated 383,000 conflict-related deaths during a similar time period, of which 193,000 were due to indirect causes of the conflict.[53] While the difficulties in calculating conflict-related deaths are considerable and methodologies vary (see ‘The Myth of Data in Yemen’), the available numbers and estimates suggest that Yemen is not the worst crisis in the world in terms of civilian deaths caused either directly or indirectly by conflict.

In addition, it is worth highlighting that it can, at times, be difficult to discern whether a death due to violence in Yemen is a result of the current conflict, or other factors. Even prior to the war, Yemeni society experienced a significant level of violence, influenced by the wide distribution and acceptance of arms within communities. A 2010 survey found, for example, that “violence accompanying land and water disputes results in the deaths of some 4,000 people each year, probably more than the secessionist violence in the South, the armed rebellion in the North, and Yemeni Al-Qaeda terrorism combined.”[54] Analysis by MSF in 2014 found that tribal disputes were at the core of most incidents.[55] When looking at a snapshot of trauma cases in Yemen in 2020, only 17 percent were considered to be war wounded.[56] These findings lined up with two medical professionals’ observations in 2019, that most of the trauma cases they were seeing were related to other violence such as fights stemming from clan feuds and qat-related quarrels.[57] The effect of aerial bombardments and the number of civilian casualties as a result of war-related violence is significant, but it is important to note that many casualties of violence in Yemen are not directly caused by the conflict itself, even if some may be indirectly related.[58]

Number of Internally Displaced People

Another key indicator of the severity of a crisis is the number of people displaced due to conflict. In Yemen, it is estimated that nearly 3.9 million people were internally displaced due to conflict as of the end of 2020 (see Figure 1.5). Compared to other contexts, higher numbers of people have been displaced by conflict in Syria, Afghanistan and the DRC.

Figure 1.5

Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre[59]

This indicator also does not support the thesis that Yemen is the worst crisis worldwide, even when taking into account the percentage of total population displaced.

Food Security and Nutrition

A key reason why the crisis in Yemen is often referred to as the worst humanitarian crisis in the world is the threat of famine, reports of which have surfaced frequently since 2017. Disputes over the data driving these reports are explored in detail in ‘A Data Case Study: Famine in Yemen’, but for the purposes of these comparisons, the official data will be used. In June 2020, UNOCHA reported that more than 230 of Yemen’s 333 districts were food insecure,[60] and the 2021 HRP indicated 16 million people were considered food insecure.[61] According to food insecurity data published in December 2020, 13.5 million people faced high levels of acute food insecurity.[62] An additional nutrition analysis also indicated more than 3.5 million children and pregnant and lactating women were in need of nutritional support.[63] While these figures merit serious concern, analysis has found that Yemen is not the most food insecure country in the world. According to the 2021 Global Report on Food Crises (which covers the period of 2020), Yemen accounted for the second-largest number of food insecure people in absolute terms, with 13.5 million people considered food insecure in 2020 (see Figure 1.6). The highest population suffering from food insecurity was the DRC, with 21.8 million classified as in crisis phase (IPC 3) or worse.[64] In addition, when looking at countries with more than 1 million people in emergency phases of food insecurity (IPC 4 and above), Yemen, with 3.6 million, ranked below the DRC (5.7 million) and Afghanistan (4.3 million), two of the comparison countries.[65] Meanwhile, Syria had the highest rate of food insecurity per capita, with 60 percent of its population food insecure.[66] South Sudan had the highest number of persons facing catastrophic levels of food insecurity, 105,000 at the end of 2020; it is considered by food security experts to be on the brink of famine.[67]

Figure 1.6

Source: Food Security Information Network (FSIN), 2021 Global Report on Food Crises

Source: Food Security Information Network (FSIN), 2021 Global Report on Food Crises

The FSIN analysis also indicated that deterioration of acute food insecurity due to conflict was highest in Syria, Nigeria, Sudan and the DRC, two of which are comparison countries. Yemen was considered to have improved its food security levels by 15 percent from 2019 to 2020, the strongest improvement in food security globally.[68]

A separate data set on food security yielded similar overall results, that Yemen cannot be described as the worst off, though the numbers varied. December 2020 integrated food security phase classification (IPC) data indicated Yemen is worse off neither in absolute numbers nor proportionally than the DRC and South Sudan, respectively (see Figure 1.7).[69] The end of 2020 also saw an alert that famine would be declared in parts of South Sudan,[70] and results in the DRC by February 2021 had designated the central African country as “host of the highest number of people in urgent need of humanitarian assistance in the world.” [71]

Figure 1.7

Source: IPC[72]

Source: IPC[72]

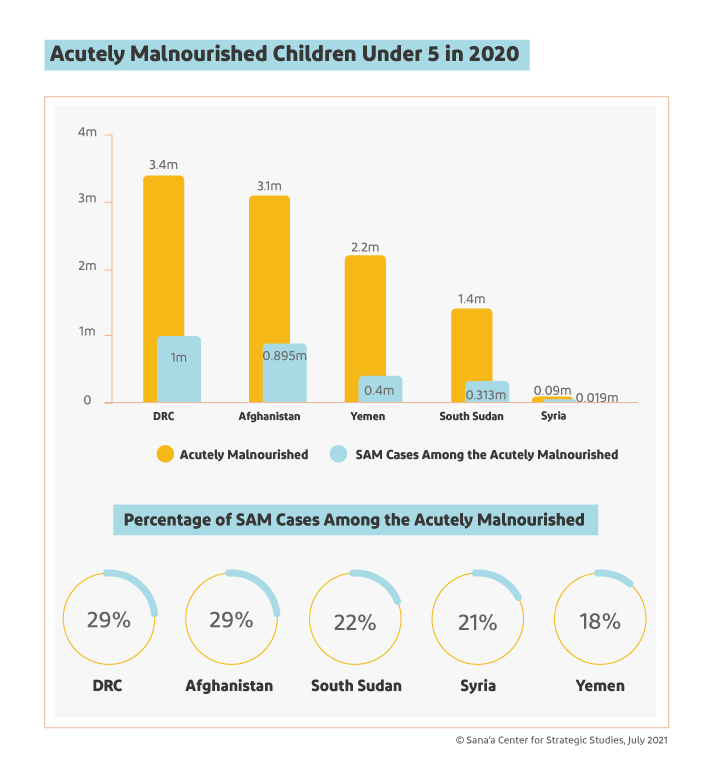

Nutrition data complements food security data, often providing a good second touchstone to identify the gravity of a food security situation. According to the data collected by the same FSIN report, Yemen does not appear to have a nutritional situation that is more serious than other comparison countries (see Figure 1.8); both Afghanistan and the DRC experience higher numbers of malnourished children.[73] The four comparison countries also fare worse than Yemen in regard to the percentage of acutely malnourished children younger than 5 classified as suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM), meaning their condition is particularly grievous.

Figure 1.8:

Source: FSIN, 2021 Global Report on Food Crises

Source: FSIN, 2021 Global Report on Food Crises

However, when looking at another indicator for malnutrition, stunting,[74] Yemen scores the worst out of all comparison countries for children under 5, as well as the worst across the 10 countries considered to suffer the biggest food crises globally.

Figure 1.9

Source: FSIN, 2021 Global Report on Food Crises

Source: FSIN, 2021 Global Report on Food Crises

Taking into account all datasets and absolute versus relative numbers, it is clear that while the Yemen food security crisis is serious, the data does not support the thesis that the situation is worse than in all other countries in either absolute or relative terms. The noted improvements to food security only cast further doubt on the continued questionable claims that Yemen is on the brink of famine. Yet Yemen gathers more attention and, subsequently, more funding, and the famine narrative in Yemen is a key factor in this despite its shaky evidence base. Additional issues regarding data collection and the veracity of food security and nutrition data in Yemen will be examined in ‘The Myth of Data in Yemen’ and in ‘A Data Case Study: Famine in Yemen’.

Health and Disease

It is extremely difficult to compare health parameters across the comparison countries, considering that all of them have near-collapsed or non-existent health systems as well as varying types of infectious disease, poorly functioning health surveillance and unreliable epidemiological data. As a snapshot to analyze the situation, a claim will be examined regarding the cholera situation in Yemen. According to reports, in 2016 Yemen saw the start of the worst cholera outbreak of modern times. Between October 2016 and December 2020, 2,510,806 suspected cholera cases were recorded, with a case fatality rate of 0.16 percent (3,981 deaths).[75] In 2019, 825,000 suspected cholera cases were reported in Yemen. Of these, 9,694 were tested – with 5,298 confirmed as cholera cases (a positive rate of 54.7 percent). Of the 825,000 suspected cases, 1,023 deaths were reported, indicating a case fatality rate of 0.1 percent.[76] In 2020, only 1,347 specimens were tested, a much smaller sample, of which just 130 (9.7 percent) tested positive for cholera.[77] Data has not been made available since the outbreak began to indicate the number of fatalities among confirmed cholera cases.

By comparison, the DRC has also seen repeated outbreaks of cholera. While the reported numbers were much lower, with 31,000 cases reported in 2019, the case fatality rate was much higher. Approximately 540 deaths were reported – a case fatality rate of 1.7 percent[78] – which would seem to indicate that cholera has been deadlier in the DRC than in Yemen. Data from earlier outbreaks indicate this is in line with previous case fatality rates in the DRC.[79] UNICEF has also recently referred to the DRC as hosting the deadliest cholera outbreak in the world.[80] Unlike in Yemen, however, all 31,000 DRC cases reported had been confirmed as cholera. Ultimately, determining which was more fatal would require comparable, reliable data from Yemen.

Putting Aid Workers’ Safety in Perspective

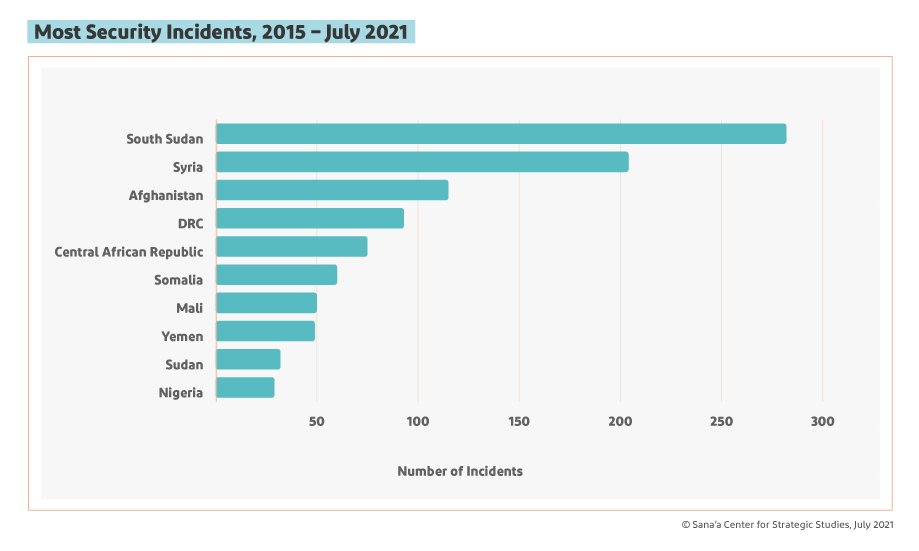

Security and access are addressed in depth later in this series of reports, but will be explored briefly here because a common narrative holds Yemen to be one of the most dangerous places in the world. Heavy security measures put in place by the UN and international organizations certainly lend credence to this idea – armored vehicle requirements, burdensome bureaucratic procedures to regulate movements, well-fortified compounds are but a few maintained over time. But how dangerous is Yemen for aid workers compared to other countries in crisis?

Overall, attacks against aid workers have been increasing worldwide (see Figure 1.10). In 2019, 483 aid workers were affected by violence directed against them, in 277 attacks.

Figure 1.10

Source: Humanitarian Outcomes, Aid Worker Security Report 2020

Source: Humanitarian Outcomes, Aid Worker Security Report 2020

The top five countries recording serious incidents against humanitarian aid workers in 2019 were: Syria, South Sudan, the DRC, Afghanistan and the Central African Republic – the same countries that accounted for 60 percent of the incidents in 2018. Syria topped the list with not only the highest number of incidents recorded, but also the most incidents resulting in death. When comparing high-incident contexts from 2016-2019, the number of attacks rose the most in the DRC.[81]

Looking at the data from 2015 to the most recent data available, Yemen ranks eighth on the list of countries with the most incidents recorded against humanitarian aid workers, with less than one-fifth of the number of incidents recorded in South Sudan (see Figure 1.11).[82] Across this time period, all comparison countries consistently rank objectively as more dangerous for aid workers than Yemen, yet security procedures in most other countries are much more flexible and conducive for humanitarian operations than in Yemen. This issue and the reasons why will be explored in more detail later in this series of reports, in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Security’.

Figure 1.11

Source: Humanitarian Outcomes, Aid Worker Security Database, aidworkersecurity.org

Source: Humanitarian Outcomes, Aid Worker Security Database, aidworkersecurity.org

Faulty Picture of Yemen’s Needs Hides a Flawed Response

The data above reveal a more complex picture of the Yemen humanitarian framework than is usually presented to the world. Yemen is portrayed by the humanitarian community as the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, and the security measures in place would suggest it is the most dangerous country for aid workers. This portrayal is not only too simplistic, it is also unsubstantiated by the data when the Yemen response is compared to other large-scale humanitarian responses, such as those in Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan and the DRC. This oversimplification often leads to inappropriate and erroneous response modalities, which continue to inhibit the development of a proper aid response in Yemen. However, while the humanitarian narrative often misrepresents Yemen and its needs, it can be a lucrative fundraising tool. Further, risk is frequently cited among the reasons for limited staff presence, an inability to reach much of the country and for what are quite possibly the world’s most arduous security procedures for a UN presence.

Beyond the accuracy of the humanitarian narrative, given Yemen’s classification as an L3 emergency, initially systemwide and still among key agencies, the corresponding systemwide mobilization of resources in terms of staff and more than US$17 billion of funding over five years, one would expect a fully functional, effective response addressing the needs of the most vulnerable. Even if addressing the needs of more than 20 million people is unrealistic, at a minimum those of the most vulnerable should be met.

Instead, a recent study by the Danish Refugee Council and the Protection Cluster found that many vulnerable people were excluded from access to aid, especially among women, displaced people, people with disabilities and minority communities. Those belonging to more than one vulnerable group, such as displaced women or people with disabilities from a minority community, were even more likely to be excluded.[83] In addition, half of participants in a 2019 perception survey conducted by UNICEF indicated that their priority needs were not being met, while only 2 percent were “mostly satisfied” with the assistance they were receiving.[84] The failure to reach the most vulnerable, despite the massive resources available, is a damning indictment of the response.

In addition, 16 of 22 humanitarian actors asked to rate the Yemen response compared to others they have worked in described it as either the worst or among the worst. These humanitarians did cite a difficult operational environment as one factor, but more overwhelmingly expressed a frustration toward the fundamental failure of the humanitarian system to understand and respond to the needs and adequately address the external challenges it faces in Yemen.

A 2015 peer review by the IASC after the first months of the L3 response in Yemen found that:

Operationally, the response is hindered by (1) disjointed leadership arrangements that were slow to be established, (2) the limited capacity of UN agencies due to security ceilings and inadequate numbers of staff in-country, (3) the slow return of international NGO staff to Yemen, as a result of visa restrictions and concerns about security and evacuation capabilities and responsibilities, (4) restricted access across Yemen due to insecurity and bureaucratic impediments, (5) a limited ability to expand operations and establish UN humanitarian hubs outside Sana’a; and (6) limited credible information and analysis on local security threats and risks, and the actual needs of people.[85]

Interviews with key informants indicate that these factors overwhelmingly remain, and this criticism applies as much now as it did in 2015. Clearly questions can be asked about whether the Yemen crisis is the worst in the world. A more fundamental question, though, is if Yemen is not the worst crisis in the world, is it possibly the worst response?

Up Next in this series of reports examining fundamental issues of concern in the Yemen humanitarian response is The Myth of Data in Yemen, which examines the reasons behind the lack of quality data in Yemen and the consequences of flawed data on the appropriateness and effectiveness of the response.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security-related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

This report is part of the Sana’a Center project Monitoring Humanitarian Aid and its Micro and Macroeconomic Effects in Yemen, funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. The project explores the processes and modalities used to deliver aid in Yemen, identifies mechanisms to improve their efficiency and impact, and advocates for increased transparency and efficiency in aid delivery.

The views and information contained in this report are not representative of the Government of Switzerland, which holds no responsibility for the information included in this report. The views participants expressed in this report are their own and are not intended to represent the views of the Sana’a Center.

- “Humanitarian Response Plan. Yemen (2021),” UNOCHA, March 2021, p. 7, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Final_Yemen_HRP_2021.pdf

- Comparisons are based on data collected in the five countries prior to 2021. Mid-2021 turbulence in Afghanistan, a fluid situation at the time of this report, is not reflected.

- Estimates of population numbers in Houthi-controlled areas range from 70 percent to 80 percent of the country’s roughly 30 million people; precise population information is complicated by the lack of a census since 2004 and internal displacement in recent years due to war and conflict.

- “Summary Human Development Report 2011; Sustainability and Equity: A Better Future for All,” UNDP, 2012, p.16, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr_2011_en_summary.pdf; Yemen currently ranks 179th: “Human Development Report 2020,” UNDP, 2020, http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/YEM

- Ginny Hill, Peter Salisbury, Leonie Northedge and Jane Kinninmont, “Yemen: Corruption, Capital Flight and Global Drivers of Conflict,” Chatham House, September 2013, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Middle%20East/0913r_yemen.pdf; Amal Nasser, “Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: Private Sector Engagement in Post-Conflict Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 2018, https://devchampions.org/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No3_En.pdf

- “Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP) Humanitarian Response Plan 2010 for Yemen,” UNOCHA, December 1, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/consolidated-appeals-process-cap-humanitarian-response-plan-2010-yemen

- Seven UN agencies, 23 international NGOs, 16 national NGOs and five government agencies; “Expansion of the humanitarian operation in Yemen – timeline,” UNOCHA, October 23, 2012, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/Expansion%20of%20the%20Humanitarian%20Operation%20in%20Yemen%2023Oct%202012.pdf. Author’s note: Partner presence has been revised because an incorrect calculation of the number of partners in 2012 was shown in the Yemen National Snapshot – Humanitarian Snapshot (as of December 31, 2012), https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/YEM_snapshot_08012013_1.pdf

- Nine UN agencies, 48 international NGOs, 42 national NGOs and nine government agencies; “Yemen: 3W Humanitarian Presence,” UNOCHA, February 12, 2014, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/NATIONAL_3W_DEC_2013.pdf

- “Yemen Mid-Year Review, 2010 Humanitarian Response Plan,” UNOCHA, July 13, 2010, p. 1, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/consolidated-appeals-process-cap-mid-year-review-yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-2010

- “Yemen Humanitarian Dashboard (December 2014),” UNOCHA, January 12, 2015, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/Yemen%20Humanitarian%20Dashboard%20Dec%202014.pdf

- “Yemen National Snapshot – Humanitarian Snapshot (as of 31 December 2012),” UNOCHA, January 15, 2013, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/YEM_snapshot_08012013.pdf

- Response funding requirements in 2015 reached US$1.6 billion, with 55 percent of that, or $885.3 million, funded. See: “Yemen 2015, Appeal Summary,” OCHA Financial Tracking Service website, https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/477/summary

- Interviews with a senior UN expert, November 5, 2020; UN senior staff member, November 13, 2020; senior humanitarian analyst, November 17, 2020; INGO staff member #7, November 20, 2020; and UN staff member #5, December 15, 2020.

- Johannes van der Klaauw, “Yemen; Exotic and utterly war-torn,” Diplomat & International Canada, December 16, 2019, https://diplomatonline.com/mag/2016/12/yemen-exotic-and-utterly-war-torn/

- Interviews with senior UN expert, November 5, 2020; senior humanitarian analyst, November 17, 2020; and UN staff member #5, December 15, 2020.

- Andrew Cunningham, “To stay and deliver? The Yemen Humanitarian Crisis 2015,” Médecins Sans Frontières, April 2016, pp. 6, 9, https://arhp.msf.es/sites/default/files/Emergency%20Gap%20Series_2_Stay%20and%20Deliver_Yemen%20Crisis%202015_April%202016_0.pdf; Panos Moumtzis, Kate Halff, Zlatan Milišić & Roberto Mignone, “Operational Peer Review, Response to the Yemen Crisis,” Inter-Agency Standing Committee, January 26, 2016, p. 10.

- These findings were confirmed by all 26 humanitarian aid workers interviewed by the author who were involved in the Yemen response between 2015 and 2020, as well as by a senior UN expert, two analysts and a journalist.

- “Flash Appeal for Yemen,” UNOCHA, 2015, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Yemen_Flash%20Appeal.pdf

- “Yemen: Areas of conflict and ongoing humanitarian activities (as of 27 April 2015),” UNOCHA, April 27, 2015, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/humanitarian_presence_conflict_27apr2015.pdf

- “Yemen: 2015 Humanitarian Response Plan (YHRP) Snapshot (as of 19 June 2015),” UNOCHA, June 27, 2015, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/yemen-ocha_hrp_snapshot_27062015.pdf

- The IASC is a forum of UN and non-UN humanitarian partners founded in 1992 to strengthen humanitarian assistance by improving its delivery to affected populations.

- Other L3 emergencies were: the Central African Republic, Iraq, South Sudan, Syria and the Ebola emergency.

- Systemwide L3s are activated by the IASC, but UN agencies can individually apply “corporate” L3 designations for their respective organizations. By the end of 2018, the IASC had deactivated the systemwide L3 designations for Yemen and Syria, the latter of which (declared in 2013) was the only systemwide L3 to have lasted longer than that in Yemen. However, all major UN agencies continue to list Yemen and Syria individually as corporate L3s. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-transformative-agenda/iasc-humanitarian-system-wide-scale-activations-and-deactivations

- For a more in-depth discussion on the origins of humanitarian aid, see: Heba Aly and Jeremy Konyndyk, “Humanitarianism, The Making Of… with Antonio Donini, Catherine Bertini, and Jessica Alexander,” Rethinking Humanitarianism Podcast, November 4, 2020, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/podcast/2020/11/04/rethinking-humanitarianism-podcast-history-origins

- “Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship,” Reliefweb, 2003, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EN-23-Principles-and-Good-Practice-of-Humanitarian-Donorship.pdf

- “OCHA on Message: Humanitarian Principles,” UNOCHA, June 2012, https://www.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/OOM-humanitarianprinciples_eng_June12.pdf

- Increasingly, civil society, private organizations and others also have been included in the humanitarian landscape, fulfilling roles to a greater extent than previously understood.

- For an in-depth look at humanitarian data over the past 25 years, see: Jessica Alexander and Ben Parker, “Change in the Humanitarian sector in numbers; A deep dive into 25 years of data,” The New Humanitarian, September 9, 2020, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/maps-and-graphics/2020/09/09/25-years-of-humanitarian-data

- Peter Maurer, “Humanitarian crises are on the rise. By 2030, this is how we’ll respond,” World Economic Forum, November 13, 2016, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/11/humanitarian-crisis-are-on-the-rise-by-2030-this-is-how-well-respond/

- “Global Humanitarian Emergencies: Trends and Projections 1999 – 2000,” Federation of American Scientists, August 1999, https://fas.org/irp/nic/global_humanitarian_emergencies.htm

- “Global Humanitarian Overview 2020,” UNOCHA, December 2019, p. 28, https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/GHO-2020_v9.1.pdf

- This amount refers to official funding provided by donors to UN-led coordinated responses and appeals, and does not include private donations, the funding of the Red Cross and Red Crescent as well as organizations outside the system such as MSF. According to the Global Humanitarian Assistance report of 2003, total funding for humanitarian aid reached US$5.594 billion in 2000, see “Global Humanitarian Assistance 2003,” Development Initiatives, 2003, p. 14, http://cidbimena.desastres.hn/docum/crid/Febrero2004/pdf/eng/doc14792/doc14792.pdf. Funding for humanitarian aid in 2019 reached US$29.6 billion, see: “Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2020,” Development Initiatives, 2020, p. 11, https://devinit.org/resources/global-humanitarian-assistance-report-2020/#downloads

- “Appeals and Response Plans 2000,” UNOCHA FTS, 2000, https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2000

- “The State of the Humanitarian System: Assessing performance and progress. A Pilot Study,” Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance (ALNAP), January 1, 2010, p. 18, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/B564B7E356934713C12576BD003FAABC-ALNAP_Jan2010.pdf.

- “Appeals and Response Plans 2020,” UNOCHA FTS, 2020, https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2020

- “The State of the Humanitarian System, 2018 Edition,” ALNAP, December 1, 2018, pp. 16-17, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/SOHS%202018%20report%20online%20.pdf

- Funding information, data related to appeals and the recipient and donor organizations can be found through the FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/. Generally accepted figures for persons in need of emergency humanitarian assistance in 2000 can only reliably be traced back to figures from the US government, and targeting at that time was based on all those determined to be in need: “Global Humanitarian Emergencies: Trends and Projections 1999-2000,” US Committee for Refugees, August 1, 1999, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-humanitarian-emergencies-trends-and-projections-1999-2000-0; For information for 2010 and 2019 on need and targeting, see: “GHA Report 2012,” Development Initiatives, July 19, 2012, Bristol, p. 4, http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Global-Humanitarian-Assistance-Report-2012.pdf; “World Humanitarian Data and Trends 2012,” UNOCHA, New York, 2012, p. 2, https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/World%20Humanitarian%20Data%20and%20Trends%202012%20Web.pdf; and “Global Humanitarian Needs Overview 2019,” UNOCHA, New York, December 2019, p. 4, https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/GHO2019.pdf

- It is important to note that it is extremely difficult to track financial resources in the humanitarian aid sector. Consolidated appeal data, for example, excludes budgets of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and MSF. Alternative estimates provided by Development Initiatives in its Global Humanitarian Assistance Reports find that between 2000 and 2019, international humanitarian assistance increased by nearly 200 percent (accounting for inflation) from US$6.7 billion (valued at US$9.95 billion in 2019 dollars) to US$29.6 billion. See “GHA Report 2011,” Development Initiatives, July 2011, p. 12, http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/gha-report-2011.pdf, and “Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2020,” p. 11.

- Aly and Konyndyk, “Humanitarianism, The Making Of…”

- WFP, for example, maintains the DRC, South Sudan, Syria and Yemen as L3 emergencies. See: “Ongoing Operations,” WFP, Rome, accessed July 11, 2021, https://executiveboard.wfp.org/ongoing-operations; UNICEF maintains Yemen and Syria as such as well. See: “Level-3 and Level-2 Emergencies (and UNICEF Emergency Procedures),” UNICEF, New York, accessed July 11, 2021, https://www.corecommitments.unicef.org/level-3-and-level-2-emergencies

- “Humanitarian Response Plan. Yemen (2021),” p. 7.

- The 2021 forecast is to target 19 million people, a figure likely distorted by the inclusion of COVID-19 targets.

- Population figures used to calculate percentages are based on UN estimates: http://data.un.org/en/index.html. Figures do not include the regional refugee response for Syrian refugees, the regional refugee response for Congolese refugees in the region and figures for South Sudanese refugees in the region. These responses are managed separately from country HRPs and bring additional numbers of people (and funding to the table); For Afghanistan the population figure was reduced by 3 million refugees registered out of Afghanistan at the time.

- “Appeals and Response Plans 2020,” UNOCHA FTS, accessed September 24, 2021, https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/overview/2020

- 2020 figures not included to remove bias related to the anomalous situation of COVID-19 funding.

- “Over 100,000 reported killed in Yemen war,” Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), October 31, 2019, https://acleddata.com/2019/10/31/press-release-over-100000-reported-killed-in-yemen-war/

- “Dashboard, Yemen 1 January 2015 – 1 January 2021,” ACLED, custom search undertaken February 3, 2021, https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard

- Figure is the mean number taken from three estimates by the Syrian Network for Human Rights, https://sn4hr.org; Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, https://www.syriahr.com/en/; and the Violations Documentation Centre in Syria, https://www.vdc-sy.info/index.php/en/about

- “UN urges parties to prioritize protection of civilians and start talks,” United Nations Mission in Afghanistan, July 27, 2020, https://unama.unmissions.org/un-urges-parties-prioritize-protection-civilians-and-start-talks

- Persistent instability over decades, the vastness of the country and difficulties in gathering data make estimating civilian casualties in the DRC especially difficult. “Dashboard, Democratic Republic of the Congo,” ACLED, accessed November 20, 2020, https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard

- Francesco Checchi, Adrienne Testa, Abdihamid Warsame, Le Quach and Rachel Burns, “Estimates of Crisis Attributable Mortality in South Sudan December 2013 – April 2018, A Statistical Analysis,” London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, September 2018, p. 2.

- Jonathan D. Moyer, Hanna Taylor, David K. Bohl & Brendan R. Mapes, “Assessing the Impact of War in Yemen on Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals,” Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures and UNDP, 2019, p. 15, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNDP-YEM%20War%20Impact%20on%20SDGs_compressed.pdf

- Francesco Checchi, et al, “Estimates of Crisis Attributable Mortality in South Sudan December 2013 – April 2018, A Statistical Analysis,” p. 2. https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/south-sudan-full-report

- “Under Pressure: Social violence over land and water in Yemen,” Small Arms Survey, Yemen Armed Violence Assessment, Brief 2, October 2010, p. 2, http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/G-Issue-briefs/SAS-Yemen-AVA-IB2-ENG.pdf

- Michael Neuman, “No patients, no problems: Exposure to risk of medical personnel working in MSF projects in Yemen’s governorate of Amran,” The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, February 18, 2014, https://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/2040#_edn2

- Data obtained by the author through a medical organization operating in Yemen, November 13, 2020.

- Interviews with two medical professionals, in Mocha and Aden, May 2019.

- For example, war-related economic hardships, the breakdown of law and order, and the loss of informal protection systems through displacement are widely accepted as contributing to increasing violence within families and in communities, especially gender-based violence. See, for example, “Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen: Preventing Gender-based Violence & Strengthening the Response,” United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), October 2016, https://yemen.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/Final%20-GBV%20Sub-Cluster-%20Yemen%20Crisis-Preventing%20GBV%20and%20Strenthening%20the%20Response.pdf, and Fawziah Al-Ammar, Hannah Patchett & Shams Shamsan, “A Gendered Crisis: Understanding the Experiences of Yemen’s War,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 15, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/files/A_Gendered_Crisis_en.pdf

- “2020 internal displacement figures by country,” Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, accessed July 2021, https://www.internal-displacement.org/database/displacement-data

- “Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan Extension June – December 2020,” UNOCHA, June 2020, pp. 5, 25-26, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-extension-june-december-2020-enar

- “Humanitarian Response Plan: Yemen,” UNOCHA, Sana’a, March 16, 2021, p. 69, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Final_Yemen_HRP_2021.pdf

- “Yemen: Acute Food Insecurity Situation October–December 2020 and Projection for January–June 2021,” IPC, Rome, December 2020, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1152947/?iso3=YEM

- “Yemen: Acute Malnutrition January – July 2020 and Projections for August – December 2020 and January – March 2021,” IPC, Rome, January 2021, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1153006/?iso3=YEM

- “2021 Global Report on Food Crises. Joint Analysis for Better Decisions,” Food Security Information Network (FSIN), May 5, 2021, p. 17, https://www.wfp.org/publications/global-report-food-crises-2021

- Ibid., p. 15.

- Ibid., p. 19.

- Ibid., p. 14; author’s interviews with food security analyst #1, November 25, 2020; food security analyst #2, December 8, 2020; and senior food security expert, January 20, 2021.

- “2021 Global Report on Food Crises,” p. 17.

- “Yemen: Acute Food Insecurity Situation October – December 2020 and Projection for January – June 2021,” IPC, Rome, December 2020, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1152947/?iso3=YEM and “South Sudan: Acute Food Insecurity Situation for October – November 2020 and Projections for December 2020 – March 2021 and April – July 2021,” IPC, Rome, December 2020, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1153003/?iso3=SSD

- “IPC South Sudan Alert December 2020,” IPC, December 2020, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipcinfo-website/alerts-archive/issue-31/en/

- “Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Acute Food Security Situation February – July 2021 and Projection for August – December 20201,” IPC, February 1, 2021, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1154108/?iso3=COD

- For IPC country-specific data, see: Yemen, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1152947/ ?iso3=YEM; Afghanistan, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1152907/?iso3=AFG; DRC, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1152857/?iso3=COD; and South Sudan, http://www.ipcinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ipcinfo/docs/South_Sudan_Combined_IPC_Results_2020Oct_2021July.pdf

- “2021 Global Report on Food Crises,” pp. 92, 132, 227, 238, 254.

- Stunting is defined as being too short for one’s age due to acute nutrition deficiencies.

- “Cholera Situation in Yemen, December 2020,” World Health Organization (WHO), February 2021, http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/cholera-outbreak/cholera-outbreaks.html

- “Cholera situation in Yemen, January 2019,” WHO, February 2019, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EMROPub_2019_EN_22332.pdf; “Cholera situation in Yemen, December 2019,” WHO, January, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EMCSR244E.pdf

- “Cholera Situation in Yemen, December 2020.”

- “On Life Support. A battered health system leaves DRC children at the mercy of killer diseases,” UNICEF, March 2020, https://www.unicef.org/media/66701/file/On-life-support-DRC-2020.pdf

- Brecht Ingelbeen, David Hendrickx, Berthe Miwanda , Marianne A. B. van der Sande, Mathias Mossoko, Hilde Vochten, et al., “Recurrent Cholera Outbreaks, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2008–2017,” Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Emerging Infectious Diseases, vol. 25, no. 5 (2019), pp. 856-864. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/25/5/18-1141_article

- Sarah Ferguson, “8 Things to Know About the World’s Deadliest Cholera Outbreak,” Forbes, March 2, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/unicefusa/2020/03/02/8-things-to-know-about-the-worlds-deadliest-cholera-outbreak/?sh=a0c2a8a471d0

- Abby Stoddard, Paul Harvey, Monica Czwarno and Meriah-Jo Breckenridge, “Aid Worker Security Report 2020: Contending with threats to humanitarian health workers in the age of epidemics,” Humanitarian Outcomes, August 2020 (revised January 2021), p. 6, https://www.humanitarianoutcomes.org/sites/default/files/publications/awsr2020_0_0.pdf

- “Highest Incident Contexts 2015 – Most Recent,” Aid Worker Security Database, custom search, July 29, 2021, https://aidworkersecurity.org/incidents/report/contexts?start=2015

- “For Us but Not Ours. Exclusion from Humanitarian Aid in Yemen,” Danish Refugee Council and the Protection Cluster, November 2020, p. 3 (non-public report).

- Sherine El Taraboulsi-McCarty, Yazeed Al Jeddawy and Kerrie Holloway, “Accountability dilemmas and collective approaches to communication and community engagement in Yemen,” Humanitarian Policy Group, July 2020, p. 7, https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/Accountability_dilemmas_and_collective_approaches_to_communication_and_communi_H0iP4yT.pdf

- Moumtzis et al., “Operational Peer Review,” p. 2.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية