Centralization with its concentration of efforts, energy and resources in Sana’a is at the root of many of the problems and inefficiencies of the Yemen humanitarian response. Despite pressure to decentralize since early in the response, decision-makers in Sana’a have been reluctant to cede autonomy and authority to the field. This lack of support has disempowered the response at a more local level, and its implications on gathering quality data and informing appropriate security measures have already been discussed. Failing to ensure the presence of field workers outside of main protected hubs also has directly inhibited good operational management, resulting in a lack of access for aid delivery and undermining the quality, speed and effectiveness of the Yemen response.

All management and coordination of activities and all decisions have been handled in Sana’a, even for areas under the control of the Yemeni government. Due to the nature of the operational environment in areas under Houthi control and the proximity to Houthi authorities, senior humanitarian leadership in Yemen and decision-makers have spent a great deal of energy reacting to events in Sana’a. This has resulted in little energy and support being focused on areas outside, where significant needs exist and a little more attention could make a big difference. Without this attention, feedback, guidance and decisions for other areas have been delayed, forgotten or ignored, which has affected the ability to respond in a timely and impactful manner in a vast swath of the country.[1] It even led, as will be described below, to overlooking three-quarters-of-a-million internally displaced persons until 2019.

Decentralization contributes to proper oversight, reducing opportunities for manipulation and mistakes and ensuring effective coordination of response activities within the country. Yet, even though recommendations to increase the number of hubs and decentralize operations date as far back as 2016,[2] only as the response entered its seventh year were some improvements being seen. Despite plans for sub-offices in Mokha, Al-Turbah and Marib in 2018,[3] it took another three years for some progress to be made. By mid 2021, most UN agencies were present in Marib. Some agencies also established a permanent presence in Hajjah, and agencies have slowly been placing some staff in the Mokha hub.[4] Despite these improvements, the substantial presence required to make a significant difference remains to be established. Presence for most agencies equates to one national or international staff member on the ground. This means that despite official presence, the difficulties related to monitoring, oversight and implementation remain much the same in practice. Some of the practical consequences of failing to decentralize are discussed below to illustrate the wide-ranging effects on operations.

Key Decision Moment within the Response:The decision of international organizations, with the exceptions of MSF and ICRC, to evacuate all international staff in early 2015 has had consequences for the response that continue to have an impact today. Needs spiked along with the war while experienced senior staff, heads of operations and decision-makers were absent, having been relocated to Amman and Djibouti. Re-entry in May 2015 focused on Sana’a, with the few staff members allowed to return confined not only to the city, but to a temporary compound and offices. Few national staff remained in locations such as Hudaydah and Aden; implementation was contracted out to third parties with little to no accountability on delivery. Security decisions remained with the UNDP resident coordinator, rather than shifting to a position with experience in delivery of humanitarian aid; a temporary humanitarian coordinator was constrained by an inflexible security framework that did not adapt to fast-changing needs. As a result, the response had little to no visibility on the situation outside of Sana’a. This had a twofold effect: The response lost both its proximity to the people and a foothold. It took almost two years for international staff to return to Aden and longer for operations to venture out of it. It has taken even longer for hubs and offices in the governorates to be reinstated. This has resulted in the operation losing an understanding of the context and operational environment, and it undermined trust and acceptance from beneficiaries abandoned during the worst time of the conflict. |

Losing Precious Time in Emergency Situations

One of the core standards of humanitarian action is to deliver aid in a timely manner.[5] While no exact time frame has been given for what is a timely response, in emergencies it is widely accepted that the initial 24-72 hours after a shock are usually critical and, especially if the shock entails casualties, that every hour counts. In Yemen, “emergency response” does not measure up to this standard. Firstly, a rapid response mechanism (RRM) was not put in place in Yemen until 2018, when about 680,000 people were displaced following fighting in Hudaydah.[6] Before this time, the humanitarian response did not work in conflict zones, and regular programming and development-oriented styles of implementation were being used despite the L3 emergency declaration.[7] Even with the establishment of the RRM, the problems were not off the table. In 2018 and 2019, the average time for an RRM to respond to an emergency was 16 days.[8] Currently, the response officially indicates that people experiencing an emergency should be reached within 72 hours of the onset of the emergency.[9] In reality, it generally still takes a week or longer to respond to events on the ground, a far from timely response, especially when life-saving assistance is required.[10]

The limited presence of staff from UN agencies and international NGOs outside Sana’a and Aden, combined with the arduous movement restrictions and procedures imposed by authorities and the UN security framework (see: ‘To Stay and Deliver: Security’), directly impact response time. This is especially problematic when it comes to emergencies such as sudden onset displacement, whether due to conflict or natural phenomena such as flooding, which require an immediate response. A more diffuse presence of the humanitarian infrastructure and staff would ensure a timely response to emergencies as well as better support for ongoing aid work as it would enable resources – staff and response items – to be in the right place at the right time.

Inability to Transfer Caseloads Leads to Manipulation, Mistakes and Lost Time

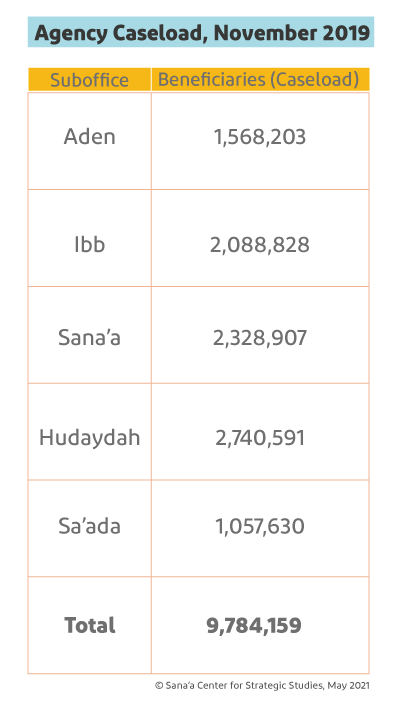

One significant challenge created by the failure to decentralize relates to caseload management.[11] Caseloads are reflected at a national level but are split across hubs, with each hub or area office responsible for the management of a certain caseload. For example, one agency serving 9,784,159 beneficiaries in November 2019 split its caseload accordingly:

Table 4.2

Source: Internal document shared with the author in 2020.

Source: Internal document shared with the author in 2020.

The division is determined by which areas fall under the responsibility of each sub-office or hub. In theory, this area of responsibility is determined logically by which areas are most accessible for each office; and they often follow official boundary lines. For example, in South Sudan, sub-offices are based out of central towns in each state: Torit, as the state capital for Eastern Equatoria, covers the state of Eastern Equatoria; Wau, as the state capital of Western Bahr el Gazal, serves as the hub for this state. As the humanitarian community in South Sudan has negotiated access to areas not under the control of the government of South Sudan, it is possible to manage aid distribution to these communities regardless of territorial control. Therefore, the model applied has an administrative rationale as well as an operational one of proximity.

In Yemen, this does not apply in the same manner. For international aid workers and official UN movements, access across frontlines is practically nonexistent. Very few official corridors exist, and while these are accessible to the general population and for the movement of commodities (relief items as well as products such as fuel), aid workers have been unable to use them because such access was never negotiated at scale.[12] When the allocation of caseloads took place in Yemen at the beginning of the crisis, it was based on territorial control combined with governorate delineation. But although the conflict has evolved over the years, including some shifts to frontlines and territorial control, the caseload allocation in different hubs and sub-offices has not. As a result, hubs remain responsible for areas that are no longer accessible to them, leading to unclear and inefficient caseload management. For example, Hudaydah sub-offices are responsible for managing caseloads in Hudaydah governorate. Yet, following the advance on the West Coast in 2018, the area immediately south of Hudaydah city returned to the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government. Many districts in Hudaydah governorate remain under split control, while entire sections of the governorate farther south along the coast fall under Yemeni government control.

Without cross-line access, the response in practice serves all areas under Yemeni government control out of Aden. Yet, caseload management has remained with the Hudaydah sub-office. This has resulted in the Hudaydah office instructing Aden logistics directly on dispatch and delivery — its managers often leaving those in Aden out of the loop — causing problems with oversight, accountability and implementation.[13] The situation has been similar for Taiz, which is managed by Ibb but includes large areas accessible only from Aden, as well as for Al-Jawf, where control over the land is split but humanitarian operations have been managed by the Sa’ada sub-office. Marib city, long under the control of the Sana’a sub-office while in territory controlled by the Yemeni government, only recently started to improve with the more functional Marib sub-office. Such a set-up impacts implementation in many ways. Firstly, due to the lack of monitoring and accountability, it opens up the system for manipulation. During 2019 flooding in Khoka, south of Hudaydah city in government-controlled territory, there was a need for emergency response. Due to the slow response from the international community, the Emirates Red Crescent provided emergency shelter and food aid. An implementing partner of a UN agency approached the Aden sub-office to deliver additional emergency assistance to the area. This was declined because the needs had already been covered. The partner then approached the Hudaydah sub-office, which remained officially in charge of the Khoka area, with the same request. Not having the full information and without coordinating with the Aden sub-office, the Hudaydah office released the request, leading to double coverage of the area. Follow-up on the matter revealed large-scale diversion of the aid distribution.[14]

Secondly, remote management of caseloads leads to an inability to understand dynamics on the ground and to mistakes. Marib city has been under the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government since the start of the war and was a safe haven for those fleeing Sana’a and its surrounding areas during fighting. By 2019, Marib was host to approximately 770,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs), by far the largest IDP caseload in the country.[15] Yet, due to decisions taken in caseload allocation, it was being managed by the Sana’a sub-office. Humanitarian presence in the area consisted solely of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and there was no international presence because of the complexities of crossing the frontlines and the unwillingness of the UN security framework to authorize missions from Aden to the area. As a result, it was only in 2019 that the international community became aware of the huge number of displaced people in Marib city, four years after the conflict broke out. Until then, the presence of three-quarters-of-a-million displaced people was somehow missed, and subsequently they went without services for years.[16] With a decentralized model under which management of Marib city would have been handed over to Aden, or had there been a separate hub based in Marib, this would have been avoided.

Thirdly, the inability to transfer caseloads contributes significantly to the lack of timely response. For example, in 2019, an offensive by the armed Houthi movement moved the frontlines in Al-Dhalea, taking territory south to the central town of Qa’atabah.[17] The caseload in this area was managed by the Aden hub and its implementing partners. As a result of the change in frontlines, populations under Yemeni government territorial control suddenly found themselves in Houthi-run territory. Those displaced or otherwise impacted by the fighting required emergency assistance. Due to the complexity and instability of the security situation, the Aden hub could not continue to manage its original caseloads, necessitating assistance from the Ibb hub. A decentralized approach would have ensured a quick transfer of caseload management between the two areas. Instead, for one UN agency alone, it took hours of discussions over months among Aden, Ibb and Sana’a management to organize assistance to the populations in need because staff from the same UN agency were unwilling to hand over information and caseload management to their colleagues in another hub. It took additional time for the Sana’a level to authorize the transfer, with at one point no follow up on the matter for almost three months.[18] By the time assistance was dispatched, at least three months had passed since the start of the fighting and displacement and one could no longer speak of emergency response. UN agencies criticized the late response, as did implementing partners, at a displacement response meeting in July 2019.[19]

Pitfalls of Coordinating Clusters in a Centralized System

Effective management of humanitarian action necessitates coordination within the humanitarian system and across the web of response partners. To address this, the “cluster approach” was introduced globally in 2006 with the purpose of strengthening leadership, accountability and technical capacity within the response as a whole. In this way, both gaps and overlap in aid delivery and activities could, in theory, be minimized.[20] Each cluster is headed by one or two persons who are responsible for ensuring activities are coordinated within their sector, whether health, shelter, food security, education, etc.[21] As it is a global system, it is difficult to adapt to different contexts, and several key informants raised concerns the cluster system may not be able to fulfill its objectives or be properly placed to coordinate the response in Yemen.[22] A 2019 internal audit of the UN coordination agency, UNOCHA, operations in Yemen also found that coordination among the clusters needed to be improved.[23] The reasons it remains problematic circle back to decentralization.

Decision-makers sitting in Sana’a, or any other hub, do not have effective reach and visibility beyond their direct environs. They are, therefore, not well placed to take decisions and react in a timely manner to sudden onset shocks. This has been seen over and over again. For example, on the west coast, several INGOs are based in Al-Mokha and have been responding to needs in the area for years. The UN only managed to establish a presence in this area at the end of 2020, and even then only had one national UN staff member based out of the hub.[24] Clusters and UNOCHA have insisted on coordinating the response from afar. One INGO manager described spending hours every month traveling to Aden to attempt to coordinate with the various UN agencies responsible for the response in the area, with little result or value.[25] In addition, when INGOs faced difficulties with local authorities in 2019 over the location of security forces near an IDP site, no coordinated support was accorded as Aden did not have capacity to provide support and Sana’a was embroiled in its own problems with Houthi authorities.[26]

Furthermore, the clusters are deeply entwined in the problematic set up of humanitarian response in Yemen, which largely takes place through authorities and institutions. The health, nutrition, education and WASH clusters have struggled to retain independence; Houthi authorities require, for example, their meetings be held with officials from Houthi-controlled ministries present. At times, these officials have served as official co-chairs of the cluster. SMART surveys presented in the nutrition cluster, for example, are approved by the Houthi-controlled Health Ministry, which serves as the co-chairing body of the nutrition cluster, including for areas not under Houthi control because the national nutrition cluster is based in Sana’a. These challenges deeply undermine the cluster system and its ability to coordinate in an independent manner. Attempts to push back have resulted in threats to shut down the cluster system as a whole and to refuse visas to cluster coordinators.[27]

Empowering Field Offices, Emphasizing Area-based Coordination

Coordination is essential for effective action, and coordination among actors who are proximate to the response itself makes it relevant, timely and impactful. Yemen is a vast country with many differences in environment, context and particularities. Copy-paste modalities do not work well. Some UN and INGO staff members interviewed for this report suggested area-based coordination[28] could be more effective as it would allow adapted modalities to be applied in a coordinated manner in delineated areas among all actors and organizations.[29]

The issues discussed above would have been avoided or significantly mitigated through decentralization. Decentralizing, however, would require decision-makers and senior management in Sana’a to overhaul the entrenched security and administrative protocols and cede authority, including in the area of resource management. Attempts to decentralize by creating sub-clusters in Aden and other hubs have not been implemented well. The same issues an internal review cited in 2016 remain today, even with the slight improvements thus far in establishing sub-offices around the country: Sub-clusters remain understaffed, lack technical expertise, do not control resources and remain dependent on the national clusters for decisions.[30] As a result, the quality and standards of interventions in areas such as shelter and camp management remain subpar compared to other responses.[31] The failure to decentralize and establish effective coordination mechanisms has not only disempowered field offices, it also has hampered humanitarians’ ability to execute an effective, timely and impactful response to people in need. One INGO staff member, reflecting on the 2020 departure of UN staff because of COVID-19, said the UN’s absence simplified response coordination because there was no one in Sana’a or Aden attempting to coordinate activities on the ground from afar, enabling local coordination: “Having no one on the ground meant no one led it — and it made it better.”[32]

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security-related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

This report is part of the Sana’a Center project Monitoring Humanitarian Aid and its Micro and Macroeconomic Effects in Yemen, funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. The project explores the processes and modalities used to deliver aid in Yemen, identifies mechanisms to improve their efficiency and impact, and advocates for increased transparency and efficiency in aid delivery.

The views and information contained in this report are not representative of the Government of Switzerland, which holds no responsibility for the information included in this report. The views participants expressed in this report are their own and are not intended to represent the views of the Sana’a Center.

- nterviews with UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN staff member #3, December 2, 2020; UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; UN staff member #4, December 9, 2020; and INGO staff members #1 on November 5, 2020, #5 on November 16, 2020, and #10 on December 3, 2020.

- Panos Moumtzis, Kate Halff, Zlatan Milišić & Roberto Mignone, “Operational Peer Review, Response to the Yemen Crisis,” Inter-Agency Standing Committee, January 26, 2016, pp. 9–10.

- “Yemen: 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan End of Year Report,” UNOCHA, Sana’a, August 2019, p. 12, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2018_Yemen_HRP_End%20of%20Year_FINAL.pdf

- Confirmed with an IOM staff member on the ground, February 7, 2021, and INGO staff in Al-Mokha at the start of 2021. In the meantime, some further progress has been made. By July 2021, for example, the hub in Marib hosted staff from IOM, UNHCR, UNFPA, UNOCHA, OHCHR, WFP and UNDSS. While IOM has had a well-established presence with approximately 14 staff, most other entities had only one or two staff present. Since January 2021, WFP and UNHCR have detached some staff from another sub-office to Marib. Only IOM and UNHCR had an international presence on the ground, one staff member each.

- “The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response, fourth edition,” The Sphere Association, Geneva, 2018, pp. 56-57, https://spherestandards.org/wp-content/uploads/Sphere-Handbook-2018-EN.pdf

- “2018 Humanitarian Response Plan End of Year Report,” p. 7; interview with UN agency staff member #1, November 13, 2020.

- Interviews with UN agency staff member #1 and UN senior staff member #1 on November 13, 2020; INGO staff member #3 on November 14, 2020, #4 on November 16, 2020 and #7 on November 20, 2020; senior political analyst, November 11, 2020; and senior humanitarian analyst, November 17, 2020.

- “2018 Humanitarian Response Plan End of Year Report,” p. 7.

- “Humanitarian Response Plan: Yemen,” UNOCHA, Sana’a, March 16, 2021, pp. 9, 126, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Final_Yemen_HRP_2021.pdf

- Interviews with UN staff member #1, November 12, 2020; UN agency staff member #1, November 13, 2020; Updated official figures for RRM response time in Yemen were not available.

- Caseload refers to the number of beneficiaries registered for a service or a distribution. For more on establishing humanitarian caseloads, see: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/Establishing%20Humanitarian%20Caseloads%20%28Dashboard%20guidance%202013%29_0.pdf

- For example, trucks can move from the port of Aden to areas under the control of the armed Houthi movement via the main transport route through Al-Dhalea, through Marib or via Taiz to Ibb. For ordinary Yemenis, travel is difficult because of the many checkpoints, but possible. However, these routes remain largely inaccessible for aid workers, especially when trying to access front-line areas. Cross-line movements for aid workers have been negotiated for special visits to, for example, Taiz and for travel in 2019 from Hudaydah City to the Red Sea Mills, but these have been exceptions.

- Interviews with UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020, and INGO staff member #5 on November 16, 2020; author’s experience in Yemen in 2019.

- Discussion the author had with INGO and UN staff in 2019 directly after the event; internal report of the incident shared with the author in 2020.

- “Yemen Area Assessment Round 37 March 2019,” IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix, Sana’a, March 2019, p. 4, https://displacement.iom.int/system/tdf/reports/Yemen%20Area%20Assessment%20Round%2037.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=5295; “Marib Mission, March 2019,” IOM, Sana’a, March 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/iom-yemen-marib-mission-march-2019

- Interviews with UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020, and UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; “Marib Mission;” and findings from the first joint UN agency visit to Marib out of Aden in April 2019 on which the author was present.

- “Yemen Humanitarian Update, Covering 7-20 May 2019,” UNOCHA, Sana’a, May 20, 2019, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/20190602_humanitarian_update_issue_08.pdf

- Interviews with UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020, and UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; author’s presence during the 2019 discussions.

- “Ad Dhale Displacement Response Meeting Minutes,” Al-Dhalea city, July 31, 2019, shared with the author in 2020.

- “What is the Cluster Approach?” UNOCHA, New York, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/coordination/clusters/what-cluster-approach

- Ibid., For more on the cluster system, see “Humanitarian Coordination Leadership,” UNOCHA, New York, https://www.unocha.org/our-work/coordination/humanitarian-coordination-leadership

- Interviews with UN agency staff member #1, November 13, 2020; UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN staff member #3, December 2, 2020; UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; UN agency staff member #5, December 8, 2020; UN staff member #4, December 9, 2020; and with INGO staff members #1 on November 5, 2020, and #10 on December 3, 2020.

- “Report 2019/126. Audit of the operations of the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Yemen,” Office of Internal Oversight Services, New York, December 17, 2019, p. 3, https://oios.un.org/sites/oios.un.org/files/Reports/2019_126_pd.pdf

- Interview with INGO staff member #5, November 16, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.; interview with UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020.

- Interview with UN senior staff member #3 November 30, 2020, and UN agency staff member #5, December 8, 2020, and knowledge gained by the author in Sana’a in 2019, through discussions within the humanitarian community.

- Area-based coordination focuses more on harmonizing response holistically in a given area, rather than within a certain sector. For more information on the approach, see: Jeremy Konyndyk, Patrick Saez and Rose Worden, “Inclusive Coordination: Building an Area-Based Humanitarian Coordination Model,” The Center for Global Development, Washington, October 2020, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/inclusive-coordination-konyndyk-saez-worden.pdf; and “Humanitarian Crises in Urban Areas: Are Area-Based Approaches to Programming and Coordination the Way Forward?” The International Rescue Committee, New York, 2015, https://www.syrialearning.org/system/files/content/resource/files/main/area-based-approaches-dfid-irc-discussion-paper.pdf

- Interviews with UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; and INGO staff member #10, December 3, 2020.

- Moumtzis et al., “Operational Peer Review,” pp. 2–3, 7, 9–10; interviews with INGO staff members #1 on November 5, 2020, and #5 on November 16, 2020; and UN staff members #3 on December 2, 2020, and #4 on December 9, 2020.

- Interviews with UN agency staff member #1, November 13, 2020; UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN agency staff members #4 on December 7, 2020, and #5 on December 8, 2020; INGO staff member #1 on November 5, 2020, #5 and #6 on November 16, 2020, and #10 on December 3, 2020.

- Interview with INGO staff member #5, November 16, 2020.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية