Introduction

Protracted complex conflicts that expose aid workers to risky operating environments are changing the way security is managed in the humanitarian community. Some of the world’s largest and longest-standing humanitarian operations — South Sudan, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Syria — are examples of such contexts that have recorded the highest numbers of attacks on aid workers year on year.[1] In addition, groups designated as terrorist entities are increasingly present within areas of humanitarian operations; Boko Haram in Nigeria, the Islamic State (IS) group in Iraq and Mozambique, Al-Qaeda in Yemen and Syria, and local groups in the Sahel are some examples. Their presence has furthered aid workers’ exposure to risk, and options are limited for negotiating safe operational environments with these groups on the ground.[2]

Yet, effectively assessing needs and delivering lifesaving assistance requires aid workers’ presence on the ground. Over the past two decades, the number of aid workers has more than doubled, from 210,000 to more than 500,000, to keep pace with a 121 percent increase in humanitarian interventions.[3] With more staff exposed to risks, the number of security incidents has also been rising.[4] Regardless of whether risk itself has increased,[5] the perception that this is the case has prompted the evolution of a security management style that separates humanitarian actors from people in need.

This can be seen nowhere more clearly than in Yemen. When the war escalated dramatically in 2015 with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates beginning an aerial bombing campaign against the armed Houthi movement, the sudden deterioration on the ground created a complex security and operating environment. Risk avoidance in the form of an overreliance on preventive and protective security measures took root early on, and this approach failed to adapt as the security environment evolved. This has prevented aid workers from being present on the ground, undermined the establishment of a quality and principled response and resulted in a failure to understand the operating environment. Information and analysis used to justify this approach remains dubious, and questioning of the status quo has been met with institutional resistance, even though the measures invoked have severely inhibited aid workers’ ability to act swiftly and effectively.

The overwhelming majority of key informants who contributed to this research considered the security framework to be prohibitive to the successful roll out of an effective, quality response.[6] In addition, a majority of operational staff interviewed noted that the security framework in Yemen was archaic, unusually bureaucratic compared to other more insecure contexts and disproportionate to the actual risk levels in Yemen.[7] Previous research supports these findings.[8]

This report, the first of two looking at how the Yemen operation implements its responsibility “to stay and deliver,”[9] examines the appropriateness of the present security apparatus and the response’s ability to assess and analyze the often-fluid and varied risks that exist in specific areas. It also considers the consequences of adopting a security-first approach, including the bureaucratic obstacles such an approach has allowed to flourish, the role the security apparatus has played in hampering a long-awaited decentralization that would place humanitarians closer to communities in need, and the response’s questionable reliance on warring parties as both armed escorts and gatekeepers. Finally, it looks at what has been lacking thus far in terms of risk mitigation measures: the component of fostering and investing in community acceptance of aid workers and the assistance they can offer.

One caveat important to note at the outset is that the analysis of the security framework below is applicable for the most part to the United Nations, and not to international non-governmental organizations (INGOs). The latter’s presence on the ground is still severely lacking, but INGOs overall have a more enabling security framework, even though some aspects, mainly pertaining to evacuation, continue to be subject to UN logistics. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) are excluded from this analysis; their independent management of security, access and logistics has allowed them more flexibility and a stronger, more sustainable presence on the ground.

The Evolution of Security Management

An increased focus on security management for both aid workers and other field staff developed in the early 2000s following several high-profile security incidents, including the murder of ICRC staff in Chechnya in 1996, the bombing of the UN political headquarters in Baghdad in 2003, the killing of Action Contre la Faim, or Action Against Hunger, staff in Sri Lanka in 2006, a suicide bomb near the UN premises in Algiers in 2007,[10] and the kidnapping of four staff from the Norwegian Refugee Council in Dadaab, Kenya, in 2012.[11] As a result, resources increasingly have been dedicated to security management. For example, the UN set up the United Nations Department for Safety and Security (UNDSS) following the bombing in Baghdad,[12] and most organizations now have dedicated security managers in programs; security management standard operating procedures (SOPs) also are now present across the board.[13] In addition to increased security management, events such as the bombings in Iraq and Algeria have highlighted the need to separate political missions, which inherently run more risk of being targeted, from humanitarian missions and premises.

Despite the challenges of complex (security) operating environments, officially the overarching premise of humanitarian response is that risk should be managed rather than avoided to ensure aid workers’ continued ability to deliver life-saving assistance. This concept was translated into the “To Stay and Deliver” policy established by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) in 2011.[14] An enabling approach to security, which the policy advocates, is defined as one in which security measures are applied to ensure programming objectives are carried out, and the UNOCHA report documented a range of methods for deploying and delivering relief in highly insecure environments.[15]

Despite an official commitment to remain on the ground and deliver in the most complex circumstances, recent years have seen an inherent struggle by humanitarian actors and organizations to put this policy into practice. This was confirmed by a follow up study in 2017.[16] Almost five years on, the situation has not improved. These findings are echoed by numerous other reports: A 2016 report found that humanitarian operations were highly determined by security conditions and that despite higher needs in locations more affected by conflict, emergencies with little or no conflict tended to have four times the number of organizations delivering assistance.[17] An MSF report, “Where is Everyone?” also highlighted that most humanitarian organizations were shying away from working in the most difficult situations or were evacuating at the first sign of trouble.[18] These reports are part of a growing body of evidence that, despite stated lofty intentions, the humanitarian sector struggles to respond where aid may be most needed. The bunkerized approach to security management that has emerged only compounds humanitarians’ safety issues; without presence on the ground, a true understanding of actual risks and how to manage them may never develop or be lost.

The Security Framework and Determining Acceptable Risk

As seen above, security management is a key component of enabling aid delivery. Good security management, therefore, should balance the need to deliver services against (acceptable) risk and be able to employ adequate risk mitigation measures. This is done through the application of a security management framework. Such a framework establishes and analyzes the risks present, and develops risk mitigation measures to reduce and/or manage that risk to enable the delivery of humanitarian activities and assistance. It is a foundational analysis for any organization working in a complex operating environment. Within this framework, it is important to remember that, while the safekeeping of humanitarian staff is important, any strategy to deliver aid should take the imperative to deliver as its starting point, not security.

The security system within the UN is complex and heavily bureaucratic; its policies and manuals encompass hundreds of pages of material. The framework and policies offer little flexibility and are often poorly understood outside the security system even though they heavily impact the ability of UN entities to carry out their mandates.[19] While the goal of the UN Security Management System (UNSMS) is “to enable the conduct of United Nations activities while ensuring the safety, security and well-being of personnel and the security of United Nations premises and assets,”[20] fieldworkers often consider its complexity and bureaucracy antithetical to this objective. The basic framework of security management is as follows:

Figure 3.1

Source: Compiled from DO and SMT Handbook, UNDSS

Source: Compiled from DO and SMT Handbook, UNDSS

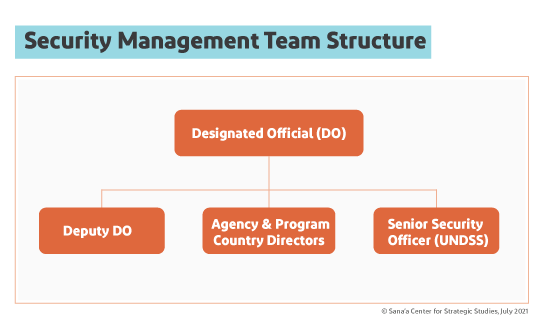

Security management is led at the country level by a Security Management Team (SMT), which is headed by a Designated Official (DO) who is the most senior UN official within the country and is responsible for final decisions on security-related issues.[21] Deputy DO responsibilities usually are handled by the second most-senior UN official in country who has taken UNSMS training. Country directors of each program or agency also sit on the SMT and remain responsible for security management of their own organizations.

In addition, at the country level, the most senior UNDSS representative creates and oversees a “security cell,” which includes security representatives for all UN agencies and programs, as well as security focal points of other organizations. The security cell is the first platform where any security related matters are discussed; it also advises the SMT and applies subsequent established measures systemwide.[22]

The UN Security Risk Management Process

The UN follows a security risk management (SRM) process to identify risks and impacts, analyze them and decide on measures to prevent or mitigate those risks so programs and aid can be delivered.[23] The policy is clear in stating that security management decisions should be based on how vulnerable humanitarians are to a threat and seek to reduce that vulnerability, not on whether a threat exists or its nature. This process of determining risk and assessing vulnerability is rarely carried out for a country or UN mission as a whole; instead, areas are generally delineated by geography and shared characteristics.[24] Specific aspects of the SRM process — including a lack of nuance in determining risk and vulnerability — will be addressed in this report as they have been identified by key informants as pertinent to challenges faced in Yemen.

Threat Assessments and Security Risk Levels

Threat assessment, including identifying actors and actions that could potentially harm the UN system, is a key component of the SRM process and is carried out by UNDSS in two parts. First, a general analysis of the prevailing security environment and hazards is undertaken in the categories of armed conflict, terrorism, crime and civil unrest. Second, threats that could specifically affect the UN are analyzed.[25]

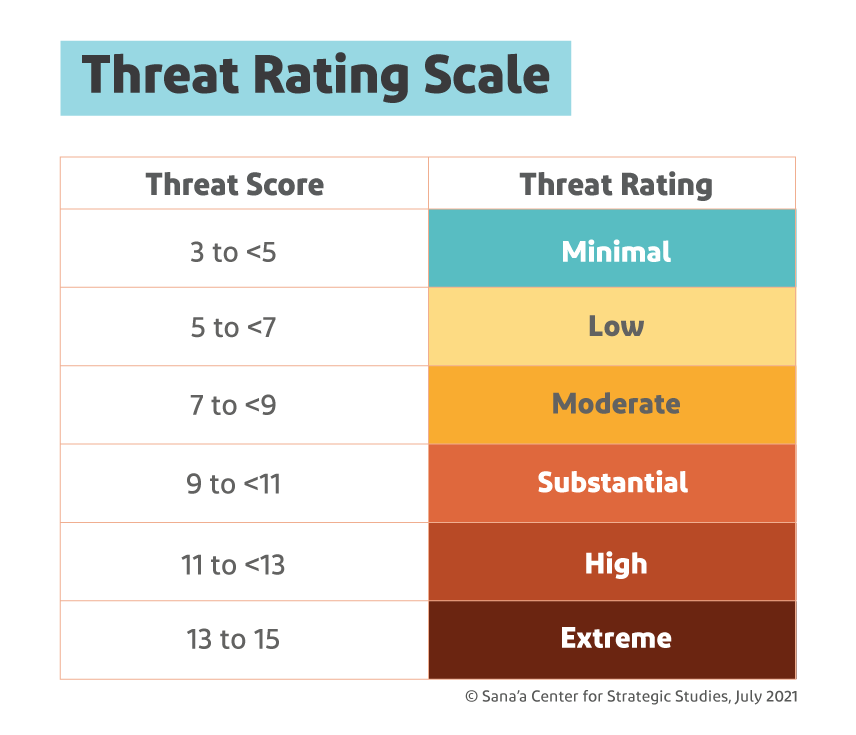

Figure 3.2

Source: SRM Manual, UNDSS

Source: SRM Manual, UNDSS

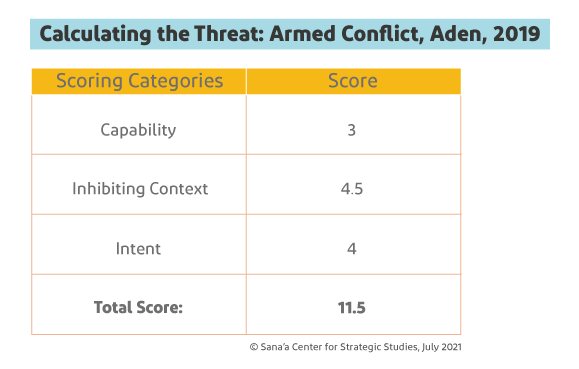

Each threat in each general analysis category is assessed on three variables — an actor or group’s intent, its capability and any inhibiting factors — with scores for each ranging from one to five.[26] A general threat assessment also considers “hazards,” which are significant non-deliberate events, whether natural such as earthquakes or human-caused such as industrial accidents.[27] The resulting “threat score” determines each threat’s rating (see Figure 3.2). For example, in the Aden area in 2019, the threat of armed conflict was rated as high:

Table 3.1

Source: Security Risk Management (SRM) Area: Yemen-SRM Area South, UNDSS, 2019

Source: Security Risk Management (SRM) Area: Yemen-SRM Area South, UNDSS, 2019

Clearly, and as the SRM manual emphasizes, a good understanding of the security situation in the area under analysis is paramount so that inputs to the analysis are relevant and based on credible facts. A vague or faulty understanding of the security environment corrupts the whole SRM process.[28] The manual is also clear that assessments are not meant to be predictive exercises; they assess the threat based on the existing situation, not on what might happen. For this reason, this sort of analysis must be repeated on a regular basis to ensure it remains relevant.[29]

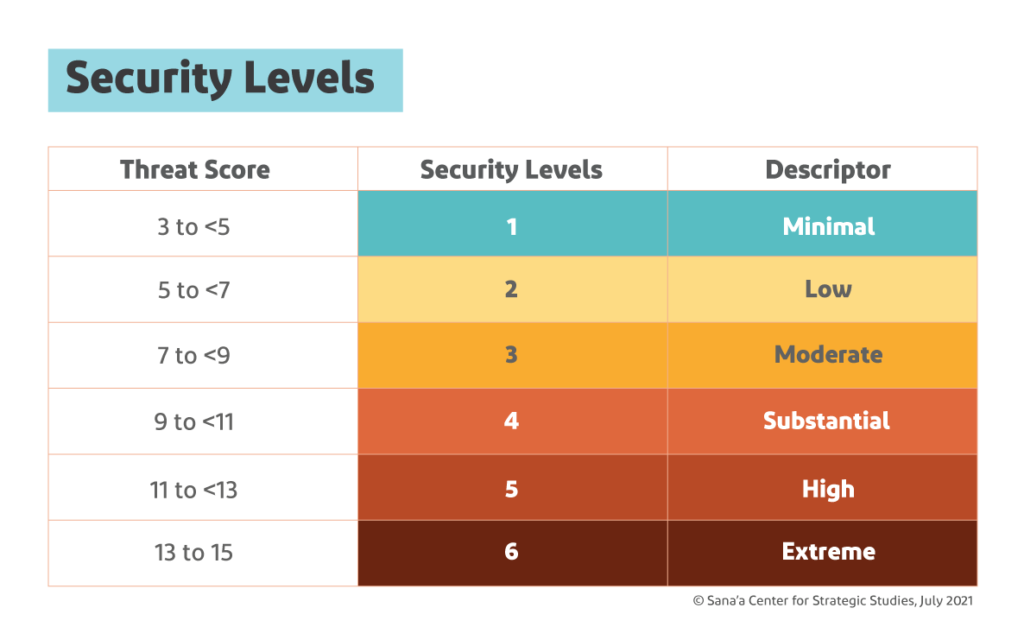

Figure 3.3

Source: SRM Manual, UNDSS

Source: SRM Manual, UNDSS

The results from the general threat assessment can also lead to the establishment of a security level for a certain area. Each threat and hazard is calculated, then each category is weighted to account for those with more serious security consequences (e.g. armed conflict and terrorism).[30] The combined weighted scores then determine the security level for the area in question.[31] Continuing the example seen in Table 3.1, the weighted score in 2019 for armed conflict in a southern zone that includes Aden became 4.6; it was added to those at the time for civil unrest (0.8), crime (2.2), terrorism (3.36) and hazards (0.12) to come up with a weighted score of 11.08,[32] or Security Level 5 (High), (see Figure 3.3).

For the second step, the assessment identifies the risk of specific threats against the UN in the SRM area. It looks at the risk of specific events that could affect the UN (e.g. kidnapping). Accomplishing this step requires situational analysis, knowledge of actual security incidents that have occurred in the area of concern, specific information and, based on these, an understanding of any trends and patterns.[33] Each potential threat is then evaluated using the same methodology as above. The threats that are ultimately identified drive the remainder of the SRM process.

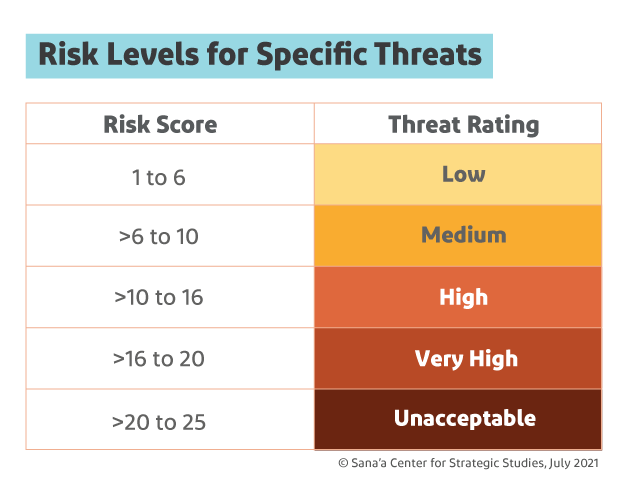

Figure 3.4

Source: SRM Manual, UNDSS

Source: SRM Manual, UNDSS

A security risk assessment follows to analyze the likelihood of identified threats occurring and their potential impact on the UN.[34] These ratings are then multiplied for each event, and the resulting scores determine the final risk of each event occurring. Finally, security mitigation measures are developed to reduce the risk of each threat.

Program Criticality

Risk scores are important not only to assess the risk of specific threats occurring, but also to clarify which activities can be carried out because only certain ones are allowed in areas of very high and high risk. These activities are defined through a “program criticality” process, which analyzes how important it is for an activity or program to take place.[35]

There are four levels of program criticality, with the first, PC1, reserved for life-saving missions or those directed by the secretary-general, and the rest, PC2, PC3 and PC4, assigned based on the activity or program’s strategic significance and the likelihood it will be implemented.[36] UN agencies and programs jointly assign categories to activities and programs, and these are then validated by the top UN representative at the country level.[37] Only PC1-designated activities are permitted in areas designated very high risk, and PC1 and PC2 in high-risk areas. PC1-PC3 activities are allowed in medium risk areas, and low-risk areas face no restrictions. In this way, risk determination also greatly impacts the modalities by which aid can be delivered.

The Yemen Security Baseline

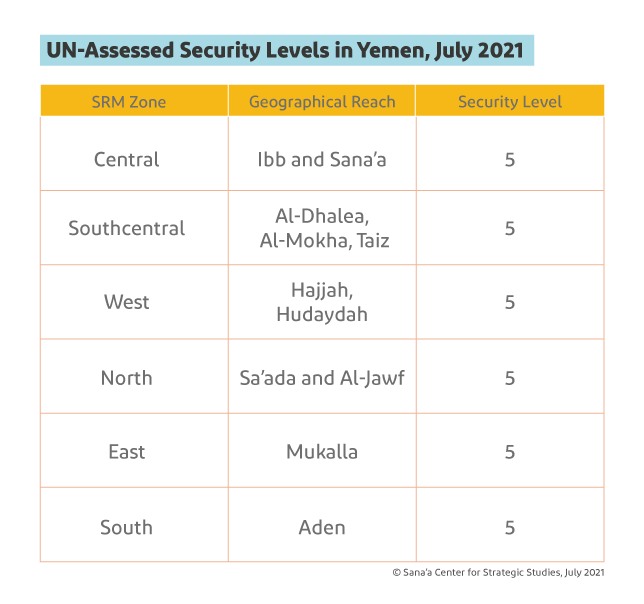

In Yemen, each of six zones (see: Table 3.1) is subject to its own SRM analysis. Designated security levels as of mid-2021 were at “high,” or five, in all of the zones on the scale of one to six.[38]

Table 3.2

Source: Compiled by the author from internal UNDSS advisories and SRM assessments.

Source: Compiled by the author from internal UNDSS advisories and SRM assessments.

The “high” security level rating is largely due to the perceived threat of armed conflict and terrorism, the specific risks of which were assessed as ranging from “high” to “extreme.”[39] In addition to this, zones within each area are further delineated into high risk and very high risk areas (in Yemen, no lower risk rating is found). Many parts of Yemen are considered “very high risk,” meaning that without a complex and time-consuming exercise in securing special authorization, these areas are off limits for UN staff.

UNDSS-designated ‘Very High Risk’ Zones (June 2021)

Sources: Compiled from UNDSS travel security advisories and SRM assessments |

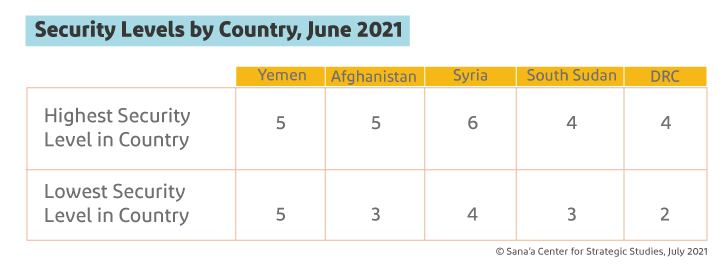

If looking purely at the security levels applicable in each country, Yemen appears overall less secure than at least three out of four comparison countries identified in ‘Challenging the Narratives’ (see Table 3.3). Afghanistan, Syria, South Sudan and the DRC, like Yemen, also are considered complex and protracted conflict emergencies and were classified at various points as Level 3 emergencies, meaning all five have seen full mobilizations of resources to address a rapidly changing humanitarian situation.

Table 3.3

Source: Travel Advisory per country, UNDSS

Source: Travel Advisory per country, UNDSS

However, these threat-level classifications across these different countries contradict other data. As detailed in ‘Challenging the Narratives’, all comparison countries rank higher in terms of aid worker security incidents than Yemen, and South Sudan has consistently ranked as the most dangerous country for humanitarian aid workers. Yet, as indicated in Table 3.3, South Sudan scores lower in assessed risk across the board. In addition, the numbers of violent incidents as a whole recorded in Syria and Afghanistan between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2020, were higher than in Yemen for the same time period.[40] Yet the security framework in Yemen, justified by UNDSS on the basis of these threat levels, has been more extensive and constrictive than in either Afghanistan or Syria. For example, Sana’a is rated as Security Level 5, and Kabul was (and, as of early October 2021, continued to be) rated as Security Level 4.[41] As a result, security restrictions have been less strict in Kabul than Sana’a, at least prior to current events.[42] In Kabul, the curfew for staff had generally been 10 p.m.[43] as opposed to 8 p.m. in Sana’a, and movements around Kabul and to the airport were made without the use of armed escorts, unlike in Sana’a.[44] This was despite more attacks on aid workers and a higher general level of violence in Afghanistan, as noted previously, as well as regular reports of significant security incidents in Kabul.[45]

Security personnel present Yemen as an inherently dangerous country, with limited geographic variation provided for the threats that exist. This is a narrative adhered to by the most senior humanitarian leadership, with one such official remarking during a 2019 visit to Aden that the southern port city was “the most dangerous city in the Middle East.”[46] Yet data looking at key indicators such as civilian fatalities, aid worker security and violent incidents does not support that narrative. In addition, humanitarian aid workers who have worked in multiple complex conflict situations, including South Sudan, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq, overwhelmingly perceived Yemen as relatively safer than other conflict areas in which they have worked.[47]

This is not to say that Yemen is without risk. Yemen remains a complex conflict involving multiple parties, and working in that context inherently carries risk. This was tragically illustrated by the death of an ICRC staff member in 2018 in Taiz,[48] three ICRC personnel in Aden in 2020,[49] the detention of UN staff members in Sana’a by the Houthi authorities in 2019[50] and an airstrike that hit an MSF cholera treatment center in 2018.[51] But these events remain relatively sporadic, and violence against aid workers has not become a normalized part of the Yemen conflict. The fundamental question is not about whether risk exists, but whether the management of that risk is proportional and the measures taken are designed to enable the delivery of aid rather than solely to reduce the risks to staff.

The Analytical Gap: Assessing Risk from a Distance

Understanding the context and environment in which a response operates is crucial on every level — crucial to understanding which needs to respond to and how, as seen in ‘The Myth of Data’; crucial to gaining and sustaining access as is explored in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Sustainable Access and Redlines’; and equally essential from a security perspective. Any analysis, whether a general situational analysis[52] or a specific threat assessment, must be based on facts. Incorrect or erroneous information can corrupt the entire process, potentially resulting in inappropriate and even dangerous security decisions.[53] This process becomes especially difficult without the right people — security analysts familiar with the general (security) environment — in place to develop the necessary knowledge and undertake a proper analysis.

One of the most significant gaps in the humanitarian response in Yemen identified by key informants was the lack of internal analytical capability,[54] which would facilitate more appropriate and better informed decisions. This deficiency is prevalent across the board, but is especially pervasive within the security sector. In the security risk management process, situational analysis is key to setting the scene and providing a good overview of the drivers of insecurity within the general environment. It forms the basis of further risk and threat analysis, and should encompass not just security incidents, but other factors including economic, environmental and social narratives.[55]

While there are a myriad of security officers present within the response – both with UNDSS and for individual agencies such as WFP and UNICEF, which have their own agency security teams[56] – only two (international) security analysts serve the entire UN operation in Yemen.[57] Both sit in the country office in Sana’a. No security analyst is present in the south for areas under the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government.[58] The option of placing UN (security) analysts in Aden, where restrictions on staff are arguably less,[59] has been raised several times with UNDSS by agencies in Aden as well as in an internal 2018 report to senior leadership in Yemen,[60] but as of mid-2021, UNDSS had yet to develop these positions in any other part of the country. Having only two analysts to cover the entirety of Yemen is a daunting, if not impossible task.[61] As a result, reliance for analysis defaults to outside analysts, many of whom are not in Yemen, and to security officers who lack the technical skills, humanitarian background and willingness to spend time in the field.

The outside analysis that is available is overwhelmingly undertaken by think tanks and humanitarian or security consultancies, including the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, the Yemen Analysis team, the ACAPS Yemen Analysis Hub, and Safer Yemen among others. While this sort of analysis is available and to some extent contracted to the response,[62] it has not necessarily been getting to those who could use it to better inform decision-making within the operation, or been used properly when received.[63] Third-party external analysis, even when of good quality, may still be of limited value because it generally does not target operational decision-making specific to needs of the response. For example, an understanding of recent or real-time dynamics in remote localities is important to operational decision-making, while external analysis is often only periodic.

Threats are not static or present all the time, and risk also evolves. Real-time information requires presence, direct engagement and relationship-building with local actors and communities. Integrating into local communities allows aid workers to understand when risks might elevate, and respond accordingly, while maintaining a presence when risk is lower. The Yemen response lacks field presence of key staff members across the country, which has severely compromised any ability to verify events on the ground. This, in turn, contributes to the limited awareness of context and environment that has led to poor operational decision making. Ironically, this lack of field presence that has left the response operating largely in an information vacuum is due to security measures in place, which will be discussed in more detail below.

With only two security analysts based in Sana’a, what passes for security and risk analysis in the response is overwhelmingly undertaken through desk research by security staff who are not trained analysts and who rarely leave UN compounds in Sana’a, Aden or their assigned hub. Analysis is mostly based on information from reported security incidents gathered from open sources such as traditional or social media, without triangulation or verification, and it is presented and used for decision-making without analysis of the impact on staff and programming or analysis within the wider context.[64] It is clearly questionable whether security analysis in Yemen meets the requirements of UNDSS’ own standard operating procedures or meets any standard of analysis.

An additional problem often referenced by aid workers is that decisions impacting the response are often taken by those who have no understanding or experience with humanitarian mandate and operational needs as well as by those with no vested interest in the humanitarian response.[65] The determination of risk and the corresponding mitigation measures directly impact implementation of the humanitarian response, both in the ability to deliver services and the modality by which the response operates. However, the typical background among security officers attempting to do this sort of analysis is within law enforcement, their home countries’ militaries or as private security contractors. The lack of a skillset related to humanitarian programming and prioritization has contributed to a protective and deterrent security approach becoming the default over a more flexible and adaptable one.

A skewed perception of risk emerges from the lack of proper situational and threat analyses, compounded by the lack of engagement with the operational environment. Along with this comes a skewed perception of reality, and the combination of the two often results in disproportionate and inappropriate mitigating measures being taken to address risk.

For example, Al-Mokha district along the Red Sea and parts of Lahj governorate have been considered by the UN as areas with an extreme threat of armed conflict.[66] Yet several INGOs have had field bases in Al-Mokha for years, including MSF, the Danish Refugee Council and Solidarites, and have been implementing programs in the area without the imposition of extreme security measures. These organizations regularly access areas such as Al-Tuhayta which are considered very high risk for the UN. Lahj hosts nearly 65,000 IDPs[67] and is a short drive from Aden. Many organizations travel there and back on a daily basis to serve communities without reporting problems, yet UN personnel struggle to gain the internal permissions required to undertake the trip. In Hajjah, Bakil al-Mir is also rated as a very high risk district, but the INGO implementing partner of WFP regularly accesses the area, including with international staff, to undertake food distributions. In another example, a road providing a shorter route to Marib was heavily mined and extremely dangerous, according to UNDSS and humanitarian security officials. However, on a visit to the area in April 2019, the UN mission found no evidence of insecurity or landmines. In fact, international oil workers on contract in Yemen had been travelling between the Safer oil fields in Marib and Mukalla, the provincial capital of Hadramawt governorate, in soft-skin vehicles without any major security incidents for several years.[68] Countless more examples exist of discrepancies between reality and the risk portrayed mainly by UN security personnel, which have delayed or canceled humanitarian missions.

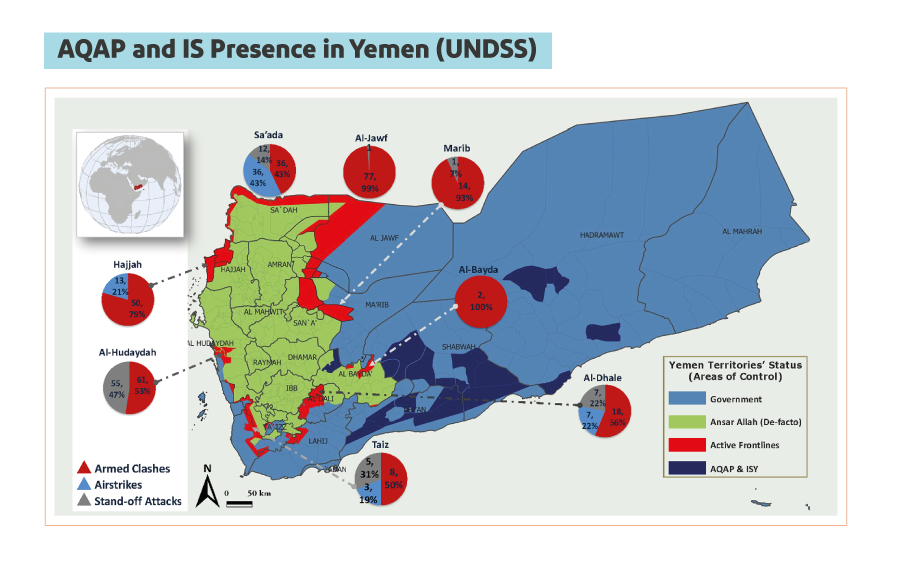

When Insufficient Analysis Skews RealityA particularly illustrative example of the consequences of an inability or unwillingness to analyze risk relates to the presence of extremist armed groups such as Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Islamic State (IS) group in Yemen. UNDSS rates abduction and hostage-taking as the major threat in Yemen, and the risk of being impacted by terrorist incidents as likely nationwide.[69] As a result, the ability to move in southern governorates has been heavily restricted. For example, travel on the coastal road between Aden and Mukalla, and between Mukalla and Marib has often been restricted and subject to UN security officials’ requirement that armored escorts accompany aid workers. This has significantly impacted the ability to roll out a field presence in the southern governorates of Abyan, Shabwa, Hadramawt and Marib, where international presence remains extremely limited. The UNDSS stance fails to take into account the particular presence of armed extremist groups in Yemen. Armed extremist attacks are largely absent in Houthi-controlled areas, though both AQAP and IS have targeted Houthi units, most often in contested areas.[70] Control by the Houthi movement and its security forces over its territory is strong, and the current risk of IS and AQAP terrorism in these areas is far less than elsewhere in the country. Furthermore, while armed extremists exist in southern governorates, their presence and strength is often exaggerated. In May 2019, UNDSS presented the following map of the AQAP and IS presence in Yemen to the SMT.[71] Figure 3.5: AQAP and IS Presence in Yemen (UNDSS)

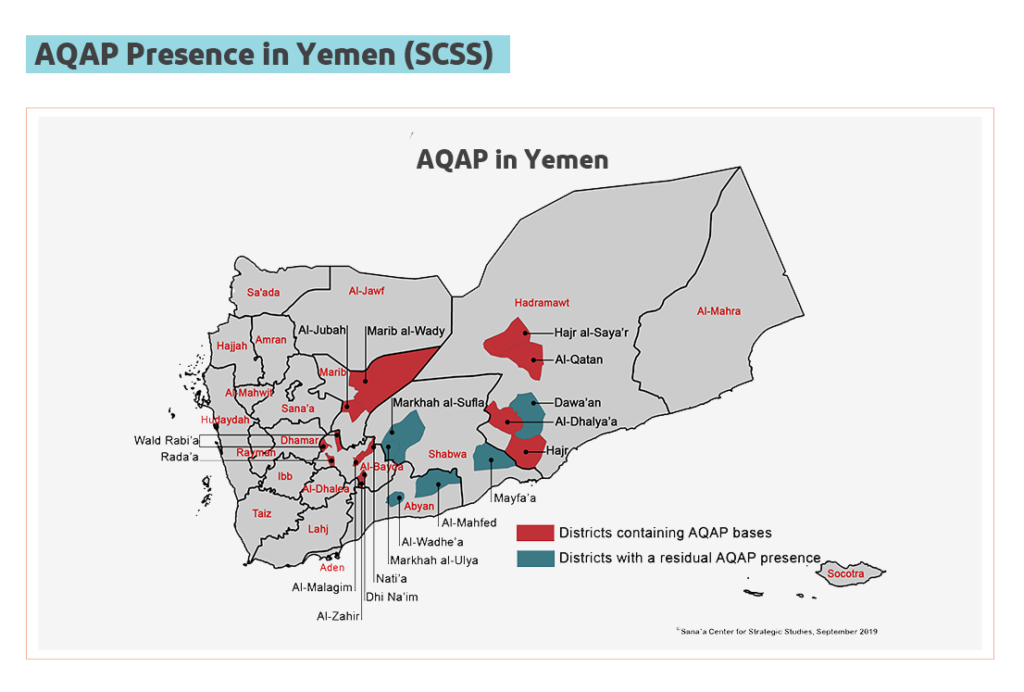

Source: UNDSS, May 2019 As pointed out by operational actors following the presentation, the map was misleading at best and incorrect at worst. The road between Aden and Mukalla was not held by AQAP or IS, nor did the groups control the territories of northern and central Abyan or east of Mukalla.[72] Regarding AQAP, a September 2019 map published by the Sana’a Center attested to the presence of armed extremist groups in the southern governorates, but clearly indicated that they did not control territory and were much more dispersed than indicated by UNDSS. In addition, conversations with local authorities at the time indicated that even in areas where the groups were present, they kept to isolated mountainous areas away from communities and main roads.[73] Figure 3.6:

Source: Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies The analysis by humanitarian security officials’ of AQAP and IS in Yemen generally has been flawed, attributing more power to them than they have in reality. Experts on Yemeni tribes and extremist groups have documented the decline in the strength of AQAP in recent years.[74] Operations by the Islamic State group, after a surge of strikes largely against rival AQAP in Al-Bayda in 2019, dropped off again in early 2020.[75] While AQAP and IS have been involved in localized attacks on security forces and key military and political institutions, most notably the August 2019 IS suicide attack on an Aden police station, neither group has directly targeted humanitarian actors. Contrary to the portrayal of UN security officials, INGOs and others travel freely through southern governorates without problems and operate in areas including Abyan and Shabwah that UNDSS claims are controlled by extremist armed groups. The more regularly these (I)NGOs work in these areas, the better they are able to analyze the risks and respond in real time to real threats with the most appropriate risk-mitigation measures. None of the INGOs in question have reported security problems related to the presence of extremist groups. One Yemen expert went as far as saying that IS in Yemen “is the most over-talked, overblown thing I’ve read in all my life.”[76] It is also interesting to note that Yemen does not feature as an active location in a recent IS campaign update newsletter detailing attacks and progress on their military campaign worldwide.[77] Nonetheless, UN restrictions for staff movements and presence based on UN assessments of the threat posed by AQAP and IS have left extensive areas in southern governorates without a humanitarian presence or services for years. Rather than defaulting to absenteeism or armed escorts for all excursions, however, a security approach committed to the principle of “to stay and deliver” would explore other options. For example, experts have noted the impacts of Houthi and tribal relations with AQAP and IS[78] as well as the role tribes play in curtailing extremist activity in general.[79] Engagement with tribal authorities can be considered a key avenue to explore for mitigating risk related to extremist armed groups in areas where the threat is present. |

In addition to poor analysis, some interviewees noted instances in which they perceived available information had been manipulated to serve source bias. Security analysis from the south, for example, would regularly get rewritten by counterparts in Sana’a to increase the sense of insecurity in Aden.[80] Aden-based staff also indicated that an unwillingness among UNDSS staff to join field missions or undertake field assessments led to claims of insecurity that delayed missions for months — and which later proved to be wildly inaccurate. This was seen at the start of the response in 2015, with researchers concluding subjective approaches to security analysis and assessing risk played a part in the delays in returning to Yemen.[81] It also was the case for the UN interagency mission to Mukalla in April 2019, which was months in the making, as well as for initial missions to Al-Dhalea requested by UN humanitarian agencies when conflict broke out in the governorate in 2019. As a result, civilians in Qa’atabah and elsewhere in Al-Dhalea were left for months without humanitarian response.[82] International staff also have routinely dismissed analysis by local security staff members when it has indicated a lower risk, despite their inherent better understanding of context.[83] Such deliberate skewing and manipulation of situational and threat analysis goes directly against provisions in the UN security risk management process, which specifically state that threats should not be assessed to fit a required profile or result.[84]

The lack of capacity and willingness within the humanitarian security apparatus to undertake the necessary analysis is not a new issue – it has been noted from the start of the response. The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) peer review in early 2016 reported that “insufficient detailed analysis [has been undertaken] to differentiate the security situation in different parts of the country” and that “security decisions have regularly been deferred to New York as opposed to making the decision at the field level based on analysis from the ground.”[85] Despite recommendations for improvement, little to no change has been noted. For example, a report to senior humanitarian leadership in Yemen in 2018 described the lack of analysis on security and operational implications as “crippling” to the response, leading to a risk-averse culture of isolation and bunkerization, and a “can’t-do attitude.”[86] This sentiment was reinforced by a majority of those interviewed for this research,[87] who noted it as a key problem and impediment to the Yemen response.

How Security Inhibits Decentralization

Proximity to beneficiaries, as previously noted, is crucial to enabling better and faster delivery of aid, better monitoring and a better understanding of the operational and security environment. Yet the response in Yemen today remains highly centralized, with the majority of humanitarian staff based out of Sana’a despite its location under the control of the armed Houthi movement and, to a lesser extent, Aden. Sana’a hosts the country offices and the most senior management roles. Initially, Aden and field hubs in a half-dozen smaller cities nationwide were intended to take on autonomous roles, ensuring a decentralized mechanism of decision-making and response delivery. This strategy has remained largely unimplemented, however, and attempts to establish the hubs have largely failed.[88] The impact of the failure to decentralize is examined later in this series of reports, but the role that the UN’s security setup in Yemen has played in its failure thus far merits discussion because, more than six years into the response, fresh attempts were being made to strengthen the secondary offices. For these to succeed and the hubs to be effective, an enabling approach to security will be especially important.

Troubles took root in the last half of 2015, right at the beginning of the emergency response, when decisions were taken that undermined the premise of adapting security management to the response rather than the response to security management. The initial cadres to return in May 2015 consisted overwhelmingly of UN security personnel and senior leadership. While leadership and security roles were and remain important, this choice created an immediate gap in strategic operational response roles with staff in operational leadership and technical positions struggling to gain access to the country. For example, the UN’s initial staff ceiling for international staff was 17 persons. Even as presence in the country was slowly scaled up to 107 slots for international UN staff by October 2015, 37 slots (a third of the available space) were reserved for security personnel,[89] impacting the ability to scale up operations in a context of high needs. The slot system remains in effect due to limited space in validated accommodation, meaning that in the seventh year of the response, security and operational personnel continue to compete for valuable space.

Staffing choices as the emergency response ramped up can also be questioned. One agency, for example, insisted that development personnel and security sector reform staff — which were key to the pre-war development-focused priorities but are not generally positions considered critical in the early stages of an emergency response — should remain as essential staff, taking up spaces that could have been allocated to humanitarian surge staff.[90] As only a few international staff of INGOs had returned by the end of 2015,[91] operational capacity at this time remained reduced across the response. In addition, security management remained until 2016 with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) resident coordinator. Keeping the DO designation with a senior official who had been leading a development response during the initial phases of the emergency response led to a disconnect between humanitarian priorities and security requirements. Development programming inherently takes place in more stable contexts with stable parameters. As such, development staff rarely have the skillset to manage emergencies and adequately balance humanitarian program priorities with security risks. This led to the security framework and decision-making process being imposed on humanitarian staff by those used to operating in a very different environment.[92]

Throughout the set-up phase, international staff were only present in Sana’a, with some national staff remaining in offices in Hudaydah and Aden.[93] A review six months into the emergency response found that the UN urgently needed to operationalize six pre-identified hubs (a number later raised to eight[94]) to bring the response and humanitarian actors closer to people in need of protection and assistance. It instructed the resident coordinator, the humanitarian coordinator and the designated official for security together with UNDSS to ensure a proactive and enabling security approach which would empower a decentralized and effective humanitarian response.[95] Despite this recommendation, it was noted two years later that UNDSS remained unresponsive to the push by UN agencies to re-establish a field presence in various locations.[96] It took four more years before the latest effort to engage hubs in the response, one that has seen them become slightly more functional with small numbers of staff present in most hubs.

The longstanding reluctance to allow staff in the field is compounded and facilitated by security measures that have been imposed within the response. They include:

- Staff Ceilings in Field Locations: Now in the seventh year of the response, staff ceilings remain in place[97] despite repeated requests to the DO, UNDSS and senior leadership to either increase them or abolish the practice, especially in field locations. The ceilings affect the ability of operational and technical staff to ensure the delivery of quality aid and to monitor operations throughout the response, often excluding staff presence in key locations. In Aden, for example, UN staff must stay in the UN enclave, which is permitted to host a certain amount of staff across all agencies. This has meant that any additional staff arriving for scale-up or for special missions were often unable to travel to Aden, impacting activities and programs due to a lack of a slot. In addition, although hubs recently became more functional, security restrictions have kept them staffed well below the country offices. For example, while in Sana’a close to 100 UN international staff are present, most agencies in Marib have only one international staff member present.[98] Considering that the need for response is in the field locations rather than the country office, these numbers are questionable.

- Security Requirements for UN Premises: The staff ceiling and presence of humanitarians are directly affected by the security requirements put in place by UN security officials. Guidelines on security management and risk mitigation strategies put in place by UNDSS require UN buildings and locations where staff are staying to conform to strict security protocols, including the installation of blast-proof windows, a secure perimeter wall, safe rooms, electronic access and permanent access to electricity and water. Needless to say, finding such a building in Yemen is difficult, especially in field locations, and upgrading often requires importing materials, which is both costly and time-consuming. Following renovation, a security-clearance process takes more time. For example, the Hajjah hub was to be established at the beginning of 2019. Until the beginning of 2021, only a temporary location had been authorized for stays up to a week for a maximum of 10 staff, including drivers.[99] Even in 2021, COVID-19 restrictions prevented humanitarian staff from using the hub, so they continued to stay in temporary accommodation when visiting Hajjah.[100] The hub in Al-Mokha, due in 2019, was only finished a year later. At the start of 2021, only a single national staff member of a UN office was based out of the hub because of continued security limitations imposed on UN international staff, despite the presence of numerous non-Yemeni INGO staff in the same area for many years prior.[101] The Mukalla site was adjusted to meet standards by April 2019; six months later UNDSS had yet to clear the premises officially for use as a hub.

These security measures, among others, have directly impacted the ability of humanitarian aid workers to be present in the field, and where needs are highest. Processes and arrangements that have hampered operationalization of hubs still inhibit efforts to assign staff where operational needs are the highest, keeping staff centralized overwhelmingly in Sana’a and to a lesser extent in Aden. Only once rebalanced is there an opportunity to deliver faster, more effectively and appropriately, to monitor better and to understand needs and the operational environment.

On Paperwork and Protection: How the Security Apparatus Hampers Response

The way the Yemen humanitarian security apparatus is set up, with an overreliance on protective and deterrence measures, disables a flexible response. Not only is the security set up “bunkerized”— shielded within fortress-like compounds and moving in armored vehicles, often with armed escorts — to the extent it is unable to adequately support field presence, it is also heavily bureaucratized. Three of the main issues brought up by key informants will be addressed below: the degree of bureaucracy required to undertake simple field missions; requirements to use armed escorts; and the warping of a deconfliction system that has handed the power to block humanitarian movements to a conflicting party.

Bureaucratic Impediments to Staffing and Executing Field Missions

The way risk has been categorized in Yemen led to the heavy protection and deterrence measures, and from this consequence grew another: cumbersome bureaucratic procedures that hamper a fast and flexible response. For example, all national and international staff members deployed in Yemen are required to complete the Safe and Secure Approaches in Field Environments training course (SSAFE) before undertaking field missions.[102] This requirement can severely delay starts for contracted field staff who have not previously received the training, as these periodic trainings are often booked out months in advance.[103] Though it initially only applied to international staff, the requirement became mandatory in 2019 for all national UN staff as well. This restricted the ability to deploy and move hundreds of national UN staff who had not been trained but held key positions in program implementation and monitoring. According to a 2019 internal email, training all necessary staff in one UN agency in Yemen through the SSAFE mechanism as per policy at the time would have taken about two years.[104] Requests to UNDSS to have the training take place in Sana’a were repeatedly turned down on the pretext that Houthi authorities would not allow it. Despite this claim, in 2019, one UN agency chose to override UNDSS, assume the risk and organize SSAFE training in Sana’a for its national staff, avoiding the time and financial burden of sending all staff to Amman.[105]

Gaining security clearances required for field missions has also impeded aid delivery in Yemen. While bureaucracy for field missions in high and very high risk areas is the same worldwide, the combination of UN security protocols, an institutional unwillingness to facilitate movements and procedures imposed by authorities on the ground make setting up movements and field time in Yemen extremely burdensome and time consuming. Any mission in Yemen is contingent on the authorization of Yemeni authorities, whether the armed Houthi movement in the north or the internationally recognized government in the south, as well as from within the UN system. All clearances must be obtained at the same time for activities to coalesce on the same dates because time frames for movements are usually specified. Ensuring everything comes together at the same time is challenging as SOPs for travel[106] laid out by UNDSS require a significant amount of paperwork and lead time to prepare.

For missions in high risk areas (the majority of Yemen) a mission security clearance request (MSCR) must be completed for any travel between hubs and cities and outside municipal boundaries. This approximately eight-page form requests a long list of information, including names of personnel, car number plates, exact route planning, GPS coordinates of locations to be visited as well as a description of mission objectives. It then requires approval from the requesting UN agency’s security personnel, followed by the agency’s head of country office. Next, it must be submitted to UNDSS at least two days prior to travel and be cleared by the DO or a senior UN security official. For round trips, separate authorization must be obtained for each leg. If multiple agencies participate in the same trip, this process must be completed separately by each agency — often meaning that one UN agency can delay finalization of the process for others. In addition, an online travel request must be submitted to UNDSS for each participant on the mission and obtained before final clearance for movement. A sign-off from the Saudi-led military coalition also must be obtained (deconfliction will be addressed below). As a result, the lead time for simple missions and movements between hubs or for monitoring purposes is approximately three to five days. In case of any “significant” changes, such as a change in participants or vehicles, the process begins again with a full resubmission of paperwork, thus delaying the mission by three to five days.

For missions considered very high risk, the process is even more cumbersome. In addition to the information noted above, the MSCR-VH form requires additional analysis of the security environment, a provision of risk mitigation measures and a justification for the PC1 categorization of the requested activity. In addition, a security officer, usually from the hub covering the area to be visited, must complete an ad-hoc security risk assessment recommending mitigation measures, which is then cleared by the chief security adviser in Sana’a. An additional document describing the concept of operations also is required. After agency approval, this paperwork must be submitted to UNDSS with a lead time of at least five working days. In addition to in-country approvals, the risk for these missions must be accepted by the executive directors of participating agencies at headquarters level, and subsequent to that, the under-secretary general of UNDSS in New York must sign off. As a result, the lead time for a mission into an area classified as very high risk is a minimum of 10 days. These restrictions immensely hamper the rapidity and flexibility of the response, and there are many moments and ways in which the process can be derailed.

Though this practice and these procedures are the same globally, other responses have cultivated more efficient and flexible ways to follow them. By way of comparison, humanitarian missions taking place in Mosul, Iraq, during the 2016-2017 battle for Mosul took 48 to 72 hours to plan and execute despite the same burden of paperwork. During the Mosul response, a dedicated team was set up to facilitate and ensure aid delivery. This team consisted of eight international access and civil military coordination staff, plus national staff who reported directly to the UN humanitarian coordinator. UNDSS staff were embedded into this team. Each staff member was assigned to prepare a certain number of MSCR-VH forms a week, which were then checked and processed by the UNDSS staff embedded in the unit itself. Each day, these MSCR-VH requests would be passed through the chain from the operational level, to the country level, to headquarters and to the under-secretary-general for UNDSS in New York, and they were returned between 24 and 72 hours later. This resulted in between 220 and 240 missions from Erbil to Mosul in the space of nine months.[107]

A humanitarian aid worker involved in the Mosul response said the main factors that made the system work were political will and establishing the correct operational culture. During the battle of Mosul, the DO and the under-secretary-general of UNDSS were supportive of the operation. In addition, there was great interest from the United States, a permanent member of the UN Security Council, in ensuring delivery of humanitarian aid. On the few occasions that UNDSS pushed back on missions, delaying aid, the US State Department would immediately raise questions, giving a powerful backing to the continuation of the process and ensuring its efficiency. As time went on, the culture of running missions and the processing of the paperwork became normalized. In addition, the embedding of security officers within the unit led to regular and consistent presence of security officers on the missions themselves, which greatly increased their understanding of the environment and allowed them to more accurately analyse risk; this, in turn, led to a better and more flexible implementation of mitigation measures that continued to support humanitarian movements and presence.[108]

Aid workers have frequently questioned why similar sorts of methods cannot be used in Yemen to expedite the system.[109] In short, the operational culture and political will do not appear to exist. Despite attempts to set up such a flow for Yemen by those who worked on both responses, pushback from UNDSS and the DO has stifled attempts to establish a more expeditionary culture in which field presence and visits are normalized and the bureaucratic process is streamlined. In Yemen, arguably the larger political investment in the response is held by UN agencies themselves, which have a vested interest in the narrative as discussed in ‘The Myth of Data in Yemen’ . More field presence would undermine the vested narrative, and as such there is little interest in facilitating this. In addition, the continued reluctance of security officers to join field missions and leave their comfort zones, along with a focus on a bunkerized security approach due to a poor understanding of risk and the environment, has hampered the rollout of a more efficient system. As seen in Mosul, effective alternatives exist, they just require internal will and keen donor interest.

The Use of Armed Escorts: When a Protection Exception Becomes the Rule

One of the biggest frustrations brought up by aid workers during the course of this research was the use of armed escorts, an issue applicable mainly in southern governorates though it has been grappled with in the north on several occasions as well. There is international guidance available on the use of armed escorts, which has been developed by the highest-level coordination forum in humanitarian aid, the IASC. Although the guidance is nonbinding, it is clear and has been widely endorsed. According to the IASC, while not forbidden, the use of armed escorts “should be used only as a last resort, in exceptional cases” after all alternatives have been considered and no other means of reaching a population to deliver aid is possible.[110]

The use of armed escorts in Yemen, particularly in the south has become the norm, even for some localized movements. This immediately breaches the requirement of “in exceptional cases.” Armed escorts are required by UNDSS on any missions outside of Aden, and until 2019 were required to move within Aden as well. This is problematic for various reasons, including that other groups or the general population could perceive humanitarians to be associated with the armed actors escorting them, undermining their neutrality. For example, using armed escorts from among security forces in Aden affiliated with the Southern Transitional Council (STC), may lead other politically aligned groups with whom the STC has come into conflict to view humanitarians as supportive of southern separatists.

This leads to a second risk — that due to this perception, traveling with armed escorts may pose a greater security risk than traveling without them. If any group or individual encountered along the way has issues with the nature or personnel of the armed escort, the escort may become a target. Escorts are armed forces, assigned by the military, who are engaged in conflict; as such, they are considered legitimate targets under international protocols on armed conflict. This is not unique to the Yemen context, but the normalization of their use in southern Yemen sets the situation apart. In this scenario, humanitarian actors risk becoming collateral damage, especially because under security protocols in Yemen, UN armored vehicles are unmarked, making their identification as humanitarian in nature problematic. This issue came to the fore in 2019 during the height of tension between the STC and Yemeni government troops. In December 2019, missions were planned from Aden to Mukalla in Hadramawt governorate and to Zinjibar in Abyan to move staff and undertake assessments. Ultimately, the missions were scrapped because the affiliation of the armed escorts would have complicated crossing the frontline. Despite this, the requirement for the use of armed escorts remained, effectively putting a halt to any staff movements, blocking needs assessments and impeding programmatic implementation.

From a purely practical perspective, the use of armed escorts also inhibits the free delivery of supplies and services. Though the presence of humanitarian staff in the south is more limited than in the north, military escorts can only accompany a certain number of vehicles per trip and are not always available. Taking into account that some missions can take multiple days, the availability of escorts becomes a logistical constraint around which missions need to be planned, leading to delays in aid delivery.

In other cases, the frequent use of armed escorts appears to have created a financial motivation for the forces relied upon to ensure the practice continues. Escorting humanitarians pays well: A convoy from Aden to Mukalla, one way, for example, can cost up to US$3,000, plus fuel.[111] This creates a financial dependence and interest in maintaining the practice.

Lastly, the use of armed escorts reinforces the bunkerization mentality and increases the distance between aid workers and beneficiaries as well as between the humanitarian operation and society as a whole. Showing up with armed actors at humanitarian sites does not create a conducive environment for dialogue, negotiation and the exploration of need. Rather, it immediately creates a hostile environment devoid of trust.

Deconfliction in the Yemen Operation

Deconfliction, a military term and procedure used since the 1970s to protect against friendly fire incidents, has more recently been adopted by humanitarians, who increasingly share the same space with military actors. For humanitarians, deconfliction is part of civil-military coordination and is most commonly defined as “the exchange of information and planning advisories by humanitarian actors with military actors in order to prevent or resolve conflicts between the two sets [of] objectives, remove obstacles to humanitarian action and avoid potential hazards for humanitarian personnel.”[112] This can include, for example, negotiating military pauses, temporary cease-fires or safe corridors to allow aid to be delivered.[113] There is no standard practice in how deconfliction is applied; more often than not it takes the form of sharing geographic coordinates with military actors, especially those with air force capability, to try to ensure the safety of humanitarian premises and/or assets. In Afghanistan, for example, coordinates of humanitarian infrastructure were shared with US and NATO forces. It can also be used in other ways. In South Sudan, UNOCHA established a deconfliction system during the crisis in 2013 to avoid the targeting of humanitarian aircraft by ground forces.

Deconfliction is considered a best practice to reduce accidental attacks against humanitarian activities, especially in complex environments, and is carried out in multiple responses, including in Yemen, Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria. It is important to understand, however, that it is an information-sharing system; it is not mandatory to ensure the safety and security for humanitarian activities. Under international humanitarian law (IHL), warring parties are prohibited from targeting humanitarian personnel, convoys and premises as well as civilians. Any such attacks breach IHL, regardless of whether deconfliction has taken place.[114] On the other hand, deconfliction does not always guarantee the safety of personnel, facilities or sites.

The efficacy of deconfliction has been a matter of debate, with questions raised about the bombing of the MSF hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, in 2015 despite its coordinates having been shared with US and NATO forces,[115] and repeated targeting of health facilities in Idlib in Syria.[116] These events prompted the UN to ask an internal Headquarters Board of Inquiry to look into the destruction or damage caused by military operations to facilities on the UN deconfliction list or to those supported by the UN. As a result, the Independent Senior Advisory Panel on Humanitarian Deconfliction was created to address recommendations made by the board.[117] While the scope initially focused solely on Syria, the panel has also begun to look into the Yemen deconfliction system.[118]

The Yemen deconfliction system was put in place with the Saudi-led military coalition following the start of its air campaign in March 2015. The initial aim was to ensure the safety of humanitarian premises from coalition airstrikes after some hit humanitarian-run hospitals.[119] The system, based on the model in place in Gaza, in the occupied Palestinian territories,[120] initially listed all static humanitarian premises; coordinates were passed to the Saudi-led military coalition. From there, the system grew to its current form. Today, three types of deconfliction are used:

- permanent deconfliction of premises, which are added to a “no-strike list” (such as humanitarian accommodations, offices, hospitals, schools);

- temporary venue deconfliction for locations such as distribution sites where humanitarian activities are implemented; and

- deconfliction of humanitarian movements, whether travel is by land, sea or air.

Currently, the deconfliction notice is created by the requesting organization through an online system and communicated to the coalition through UNOCHA, which acts as an intermediary ensuring that notifications are submitted correctly in a standardized manner. Acknowledgements of deconfliction notices are passed back through UNOCHA.[121] No deconfliction system is currently in place with the armed Houthi movement.

One of the main concerns raised by various key informants interviewed was that the system, which began with lofty intentions to safeguard humanitarian premises, has grown beyond its initial scope.[122] As discussed above, deconfliction is a voluntary notification system. In Yemen, the humanitarian community, and in particular the UN, has allowed the procedure to evolve to a point in which the coalition has established the power to block humanitarian movements. The UN considers deconfliction confirmation as mandatory for any movement or site visited by staff. If explicit acknowledgement of deconfliction by the Saudi-led coalition is not given, both the coalition and UNDSS consider a movement or location unauthorized under the current security management framework, and access to that location is denied.[123] For example, a major challenge faced by humanitarian organizations in 2019, was at Dubab checkpoint between Aden and Al-Mokha. The checkpoint was manned by Emirati forces, who refused passage to any humanitarian convoy or movement unable to provide proof of deconfliction with the coalition. This delayed or stopped many movements.[124] In addition to the practical ramifications on operations, this is in direct contravention to the IHL premise of freedom of movement of humanitarian personnel and goods.[125]

The process has also become time consuming and heavily bureaucratic. Deconfliction information needs to be submitted to the UNOCHA deconfliction team in Riyadh through an online system at least 72 hours in advance. This information is then passed to the military coalition’s Evacuation and Humanitarian Operations Committee (EHOC), which will either acknowledge or return the deconfliction notification.[126] This lead time is an additional impediment to a quick and life-saving response. For example, if a sudden displacement of population occurs, under the current deconfliction system a response would only be able to reach the affected population after three days (and considerably longer considering UN Security procedures). Missions can also often be left in limbo until clearances come through, which impedes planning and efficiency. The 72-hour requirement also has a significant impact on United Nations Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) staff movements. Passenger manifests are required to be submitted to coalition authorities at EHOC at least 72 hours in advance; no changes to the manifest are accepted after submission unless for medical evacuation purposes. This has meant essential staff have regularly been unable to travel into the country or between Sana’a and Aden on short notice.

In addition, the list of deconflicted locations in Yemen is arguably unmanageable. In late 2018, The New Humanitarian reported UN figures of up to 30,000 static deconfliction locations and Saudi figures of more than 64,000 deconflictions, though it wasn’t clear whether the Saudis also were including past temporary deconflictions.[127] The management of such an extensive list is immense, raising the possibility of mistakes or information being disregarded due to an inability to cope.[128] Indications from the EHOC team are that staff regularly feel overwhelmed by the amount of deconfliction requests submitted, which increases the time needed for processing.[129]

The system in place has also impacted humanitarian neutrality. Following a decision in 2015 made by the then-UN resident coordinator and DO to deconflict all locations that were humanitarian as well as those with presence of UNDP liaison officers, the majority of Houthi-controlled government buildings in Sana’a were put on the no-strike deconfliction list.[130] To date, many of these locations, including the Houthi-run Ministry of Foreign Affairs, remain on the UN no-strike list despite their inherently political character.

In addition, the information requested for deconfliction and passed to EHOC is extensive and surpasses what is needed to avoid accidental targeting. Even for land movements, full details of all staff members (names, phone numbers and other personal information) must be provided as well as pictures of the vehicles from all sides, precise GPS points of locations being visited, and a detailed description of any cargo and its use. This far surpasses information needed to avoid targeting a movement, location or convoy, and it is unclear how this information is used.[131] The deconfliction system has arguably moved toward the response having to prove the humanitarian nature of its activities. It also calls into question the independence of the response as it gives a party to the conflict access to extensive information that can be used to block movements and activities as per their will.

Lastly, a common complaint among humanitarians is that deconfliction is required in locations that do not have, and in some cases have never had, active conflict.[132] The southern governorates under the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government supported by the coalition are largely not affected by airstrikes; the air campaign targets areas under the control of the armed Houthi movement. Yet, both the coalition and the UN security management framework require the same process for government-controlled areas, which amounts to an unnecessary bureaucratic impediment to the flexibility and efficacy of the response.

Acceptance, a Missing Link in Risk Mitigation in Yemen

Responsible security management requires not only preventive measures to avoid an incident, but also investing in the capacity to manage an actual crisis situation and the consequences of a critical incident. A key finding that came to light during discussions with humanitarian staff during this research is that beyond a certain comfort with a bunkerized set up, the current security approach continues because other mitigation measures have been inadequately considered.

Acceptance is a risk management strategy that rarely has been used in Yemen, even though it was adopted in 2019 as a pillar of risk mitigation within UN security management and officially is part of the SRM process.[133] It is based on reducing threats to aid workers by reducing others’ motivation to harm them and rests on three core factors:

- the quantity and quality of aid provided;

- the degree to which this aid is valued; and

- the social distance between aid beneficiaries and parties considered a threat to aid workers or resources.[134]

The stronger the acceptance by communities, the stronger the ability to mitigate risk. If beneficiaries and communities accept and value the services and aid provided, they will often go out of their way to protect those providing the aid. Though frequently discussed, the concept of acceptance is often poorly understood. It is often assumed that good, community-based programming will automatically lead to acceptance, but it is important to recognize that acceptance is a continuous process, based on trust, that is built over time. It needs to provide a clear value but also requires consistent engagement with stakeholders and continuous dialogue. An active acceptance strategy, continually maintained, is what leading researchers in the field advise is necessary to be effective.[135]

Ways to Promote Acceptance

Source: Jackson, “Acceptance Strategies in Conflict,” (2015) |

Local perceptions of humanitarians and aid organizations are influenced by project design and accountability, adherence to humanitarian principles, staff behavior that is respectful of cultural norms and whether the agency understands the dynamics among various key interlocutors. While acceptance is particularly important from a community perspective, it is also key to gaining acceptance (and consent) from those who would have an interest in blocking the delivery of aid or harming those who deliver it. For this reason, acceptance is not only contingent on just delivering aid, it is an approach to risk management that requires diplomacy and negotiation.

Gaining and managing acceptance takes time and a sustained effort. As a strategy, it needs to be flexible and adaptable to context; it is not one size fits all. For this reason, many organizations prefer to rely on deterrence and protection methods, and this is especially true for the UN and its agencies, which have limited interaction with beneficiaries and the operational environment. A risk management approach that tries to physically deter threats with walls and armored vehicles, rather than reducing the desire of actors to harm an organization and its staff may prevent attacks in the short term. However, this approach has longer-term consequences for the ability to stay and deliver and does not reduce risk in a sustainable manner. This is evidenced in Yemen in how, as the response continues, the UN still struggles to put staff in the field and deliver aid while grappling with negative perceptions. Conversely, organizations with a different approach, such as MSF and ICRC, which focus on presence and acceptance as their main risk mitigation measures, have been able to provide quality responses that have the flexibility to adapt to needs and conditions. This clearly evidences that operating under this modality is possible in Yemen.

Restoring the Goal of Enabling Humanitarian Work

The goal of any humanitarian response is to provide assistance. Often, this takes place in contexts that are volatile, have various forms of insecurity and are complex. For this reason a balance has to be struck between delivering aid and keeping staff safe. Managing risk and putting in place appropriate security measures are a key aspect of enabling humanitarian work, but managing security is not intended to be an end in itself or an obstacle to the delivery of aid.

Good security management must be based on a sound understanding of the environment that the response operates in, the threats present and the risks faced by staff and the organization as a whole. This can only be done through proper analysis based on facts and by having a consistent presence on ground, which builds awareness and familiarity. Once this understanding has been established, appropriate and sustainable risk mitigation measures must be put in place that facilitate and enable aid delivery. Otherwise, risk mitigation becomes one of the biggest barriers to this goal.

In Yemen, however, security management has become an end in itself, with those trying to deliver aid regularly at odds with a security system that does not support this objective. The problem starts with a lack of analytical ability and an unwillingness to engage with the environment, which has led to a skewed perception of threats, risk and the environment in general. Security officers are quick to frame Yemen as an inherently dangerous country where staff run the risk of being kidnapped by extremists or getting caught up in armed conflict when they leave the compound. Yet there is no evidence of this. Most aid workers with experience in multiple crises spoke of feeling safer in Yemen than in most operating contexts, and data presented on aid worker insecurity would appear to support their perception.

This lack of proper understanding has led to the implementation of high risk levels across the country, which not only results in risk mitigation measures that rely heavily on protection and deterrence and focus on bunkerization, but also in heavy bureaucratic procedures that severely hamper quick and efficient aid delivery. As a result, UN aid staff spend more time attempting to process paperwork than actually implementing activities in the field.

The focus on bunkerization and inhibitory processes have resulted in an extremely limited field presence of UN staff and operations across the country. This lack of presence reinforces the vicious cycle of incapacitating analysis and understanding, only reinforcing bad practices that have become entrenched within the system. In addition, this lack of presence and bunkerized approach increases the disconnect between humanitarian aid staff and the Yemeni population, reducing not only quality delivery but acceptance, fundamentally undermining the ability to manage risk.

Calls for change within the security system, and for a more enabling approach, have been present since early on in the response. Yet, these calls to date have fallen on deaf ears with no one apparently willing to take on the responsibility of changing the status quo, assuming more risk and forcing the system to perform better. Security staff have come to be seen as gatekeepers, failing to enable humanitarian access and increasingly dictating operations. Unless a better way forward is found, the response will continue falling short in achieving its objectives, which will, ironically, only lead to more risk.

Recommendations

There is an urgent need to overhaul the security management system in Yemen. The manner in which it currently functions is directly impeding the delivery of aid, and preventing the ability of aid workers to be in the field. At minimum, better analysis of the context and risk would ensure the response understands its security environment correctly and is able to take appropriate mitigation measures that still allow it to fulfill its duty to stay and deliver. Security protocols need to become more transparent, flexible and efficient. A serious and practical discussion should be had on how to enable aid workers to be present in the country as well as in the field, and to remove unnecessary infringements that complicate their ability to move throughout the operating arena.

To Senior Leaders of The Yemen Humanitarian Response:

- Put in place a team of access and security staff tasked with enabling efficient staff movements and aid delivery (such as the Mosul model).

- Overhaul the deconfliction mechanism in Yemen to create a simple, efficient and effective system that enables free movement of aid workers and aid. To this end:

- Return to the premise that notification of a movement is sufficient without subsequent acknowledgement or permission from the Saudi-led coalition, thereby ensuring EHOC cannot use the deconfliction system to block aid for its own interests;

- reduce the information passed to EHOC to ease the data load, ensure shared data cannot be used for other purposes and to end any notion that aid delivery intentions must be justified to warring parties;

- address the feasibility of managing tens of thousands of sites by establishing a panel to fully review all permanently deconflicted sites to ensure their humanitarian nature and reduce the list to essential sites only; and

- end the restriction on UN staff movements that lack proof of deconfliction, recognizing the current restriction as an inappropriate tool to block staff movements.

- Create a more enabling environment within the response. To this end:

- Remove the slot-level system from the response to enable staff to move into and throughout the country;

- create additional accommodation to support more staff presence where necessary, especially at field level; and

- review the process for field missions to reduce bureaucratic procedures so staff are more easily able to move to the field.

To UNDSS:

- Undertake an immediate review of bureaucratic impediments resulting from the UNSMS and review the burden of the bureaucratic procedures on the response. While this should be done globally, Yemen could serve as a good case review.

- Ensure that UNDSS becomes a field-focused entity and decentralizes by taking staff members out of Sana’a and ensuring their presence nationwide to inform security and risk analysis. More staff should be based in the field than in Sana’a instead of the other way around.

- Prioritize skills developed through previous experience enabling humanitarian programming when hiring security officers rather than defaulting to candidates from law enforcement, military or private security backgrounds, where more rigid deterrent approaches are the norm.

- Reform the application of SRM procedures to ensure context and threat analysis are based on facts and adhere to SOPs and international standards. The analysis should focus on the impact of the work and mandate of UN personnel rather than generalized broad analysis. To this end:

- Ensure at least one security analyst is based in each hub as well as in Sana’a and Aden to ensure quality local security and risk analysis;