Introduction

Access to populations in need is essential to humanitarian operations, and in conflict situations, how unimpeded and sustainable that access is depends heavily on how willing warring parties are to cooperate with humanitarians in territories they control. In the case of Yemen, aid delivery, therefore, depends largely on the willingness of the armed Houthi movement in the north and the internationally recognized Yemeni government in the south as well as the Saudi-led military coalition. However, an important part of the responsibility for ensuring access also lies with the humanitarian community itself. Humanitarian actors have a responsibility to set the parameters of the operational space and to foster an environment in which programs and activities can be implemented in an independent and impartial manner. On both counts, Yemen often falls short.

The operating environment in Yemen has frequently been described as one of the least permissive in the world,[1] and recent analysis states that 19.1 million people, two-thirds of the population, were hard to reach by the end of 2020 due to conflict as well as logistical and bureaucratic hurdles.[2] Operational interference is rife in areas under the control of the armed Houthi movement, where operational space has shrunk over the years with a marked drop noted in 2019. While access constraints are experienced across the country, the typology and who is responsible varies between areas controlled by the Houthi authorities and those run by the internationally recognized Yemeni government. In general, however, the operational environment has remained more permissive in government-controlled southern areas, even though the response has not necessarily taken advantage of that.

Access to populations in need can be challenging for a variety of reasons. Some of these arise from the operational environment, such as nearby frontlines making visits more dangerous for aid workers. Other obstacles are rooted within the response itself, such as the inappropriate, ill-informed and overly bureaucratic security procedures that have confined staff largely to Sana’a and Aden, and which were examined in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Security’. Failing to decentralize decision-making and response also has far-reaching effects on aid delivery, leaving it more open to manipulation and mistakes (See: ‘A Centralized Response is a Slow, Ineffective Response’). All of these factors impact access to communities for the delivery of response.

This report acknowledges the constraints on access, administrative and operational,[3] imposed by those authorities who control territory, but more specifically it examines how the response handles these challenges. In Yemen, the humanitarian response itself has contributed to a highly restrictive environment by essentially abdicating its duty to enforce redlines in response to challenges and create the operational space needed for aid delivery. Failing to establish and preserve operational space has not only reduced access, it also has allowed authorities in northern Yemen, who have a vested interest in the implementation of the response, to present themselves as the solution to access impediments they have largely created for their own benefit. Ending this arrangement in favor of a comprehensive operational and access strategy, and addressing internal issues that contribute to the overall stagnation and unhealthy operational culture throughout Yemen, would improve the operating space and allow for a more effective response. Doing so, however, risks jeopardizing established relationships – ones made harder to replace by the response’s failure to understand and develop relationships on the ground. Yet, if the fundamental problem of access to people in need cannot be resolved, then the response serves little purpose.

Constraints on Sustainable Humanitarian Access

Often when considering access, efforts and attention are focused on reaching a population once. If reached once, whether with a one-off food distribution or with a single service such as the provision of clean water, the response as a whole can record success for the year in having reached a targeted population and will claim that there is access to that population. But reaching a population in need once neither alleviates suffering in the long term nor ensures a minimum standard of aid provision to affected populations. Ultimately, humanitarian assistance can only have a successful impact if it can be delivered to people in a consistent manner over a longer period of time. This requires sustainable access, even when some obstacles and risks are present. And sustainable access in Yemen is a fundamental problem.

To track access impediments in a consistent manner, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) has developed tools that are used in responses globally.[4] Using these tools across humanitarian responses is thought to ensure consistent and correct reporting and tracking, and to enable comparisons. One of these tools is the Access Monitoring & Reporting Framework (AMRF), which is used to collect and analyze data on the impact of access constraints. It is used to develop context-specific indicators for the most relevant constraints to a response. Many of these types of constraints are apparent in Yemen, overwhelmingly in northern areas under the control of Houthi authorities where the majority of Yemenis live. In Yemen, like elsewhere, this data is usually used to develop access snapshots, which offer a quick look at the most widely reported access constraints by humanitarian partners on the ground.[5]

Access Constraints Laid Out in the AMRF Framework[6]

|

In Yemen, UNOCHA consistently tracks concerns in all but the first of the AMRF typologies (denial that need exists) on a monthly basis. Overwhelmingly, the number one access constraint reported is the restriction on the movement of humanitarian organizations, personnel and goods to and within Yemen, followed closely by operational interference; more than 90 percent of complaints reported involved bureaucratic restrictions.[7] Most of these restrictions are imposed by Houthi authorities in areas under their control. For example, in 2019, 93 percent of the movement restrictions were attributed to Houthi authorities.[8]

Access in Areas Controlled by Houthi Authorities

Challenges around establishing adequate operational space and negotiations for access have been taking place in Yemen for decades, not only with the formal government. During the Sa’ada wars (2004—2010), humanitarian organizations were already negotiating with the armed Houthi movement to access areas in Sa’ada affected by conflict.[9] A 2016 analysis of the operating environment in Yemen identified ad hoc restrictions on humanitarian movement, increased assertiveness with regard to travel permissions, shrinking humanitarian space, interference in activities, threats against humanitarian staff and delays in approvals of sub-agreements and visas as key issues facing the humanitarian response.[10] That list is almost identical to current constraints. Today, in areas under the control of the armed Houthi movement, adequate operational space and access are almost nonexistent. The top three access constraints reported by humanitarian partner organizations in Houthi-controlled areas are movement restrictions, bureaucratic impediments, and operational interference.[11] Challenges surrounding interference in beneficiary selection, appropriation of aid by authorities, visa and movement blockages have been well documented in recent years.[12]

Despite a common perception that the operational environment is worse now than it was previously, the deterioration is hard to quantify. The 2010 humanitarian response plan already referenced limited access to areas in need.[13] Humanitarian personnel present in 2015, after the Level 3 emergency was declared, said that access was problematic from the start, though no baseline was established at that time.[14] Relatively, however, humanitarians interviewed indicated that Houthi authorities were more open and permissive at the start of the response, and that the situation deteriorated over time as Houthi authorities slowly began to take over more institutions and centralized power, pushing out previous technocratic cadres from institutions and ministries.[15] In particular, key informants identified three events as significant in pinpointing the deterioration in operational space and humanitarian access: the November 2017 Houthi directive creating the National Authority for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Aid (NAMCHA), the death less than two weeks later of former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh, which left the Houthi movement solely in control of state institutions in Sana’a, and the November 2019 creation of a new coordinating body, the Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA), which centralized management of all humanitarian affairs in Houthi-run territory under one body.[16] Each of these events signified a consolidation of power and control within structures and by Houthi authorities and hardliners (compared to the more moderate GPC technocratic officials who had remained in place in the initial phases of the response). This, in turn, increasingly narrowed the scope of actors with whom to negotiate, allowed for less leverage and resulted in a harder line being taken by those who assumed power.

Access in Areas Controlled by the Internationally Recognized Government

While in the north the Houthi authorities have actively sought to constrain the operational environment and access, the situation is markedly different in areas under the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government. Authorities governing the south have remained supportive of aid organizations and largely facilitate access. Increased delays relating to the signing of NGO sub-agreements have been noted,[17] as well as challenges in areas such as moving humanitarian cargo across the south-north supply pipeline. However, these challenges have not fundamentally reduced the capacity to deliver aid in the south, and the operational environment in government-controlled areas remains largely permissive; NGOs are able to regularly access conflict and frontline locations such as Hays and Al-Tuhayta in Hudaydah governorate. All humanitarian aid workers interviewed for this report who were experienced with operations in northern and southern Yemen indicated that access issues attributable to the internationally recognized Yemeni government were minimal in areas under its control and were manageable with the right approach and strategy.[18]

Largely free of the external interference and restrictions imposed in the north, several humanitarians interviewed indicated that access challenges in government-run areas were, for the most part, attributable to the internal UN/humanitarian security management framework[19] (discussed in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Security’). One humanitarian practitioner boiled down the issues of access in the north versus the south: “Where we can’t, we try; where we can, we don’t.”[20] As a result, large areas under government control remain unassessed and lack the presence of a quality response.

As noted above, access challenges imposed by authorities throughout Yemen have been well documented, but what has remained less clear is the humanitarian community’s strategy to manage and mitigate these impediments. The rest of this report will explore gaps within the Yemen response that relate to access, and internal choices made that have led to the reduction of the humanitarian community’s operational space in Yemen.

A Shaky Foundation: Setting Up the Yemen Operational Environment

A key weakness of the humanitarian response has been a lack of a comprehensive operational and access strategy from the start. Typical to any emergency response, initial negotiations conducted with the emerging authorities in the north were undertaken with little thought to medium- and long-term consequences. Interviews with three interlocutors present at the start of the L3 in 2015 indicated insufficient consideration was given, for example, to putting in place standard operating procedures (SOPs) or agreements relating to the movement of personnel and goods or the issuing of visas.[21] As a result, most issues were negotiated on an ad-hoc basis, subject to change at the will of the Houthi authorities and, in the first two years, their allies within Saleh’s General People’s Congress party. Failure to address these practices in the early years of the response meant that until today discussions on SOPs with Houthi authorities have failed to materialize.

Key Decision Moment within the ResponseIn 2015, the humanitarian response took over from a development-oriented response and structure. No international staff were present outside of Sana’a at the time; they had been evacuated when the war escalated in March. As a result, institutional knowledge and connections made in years prior by development staff were lost during the transition to an emergency response. A tendency to look for quick fixes to this shortcoming at times resulted in poor choices. For example, surge staff in one UN office hired an interlocutor from within the armed Houthi movement as a liaison officer to manage the relationship with the new authorities and negotiate for the movement of humanitarian staff and the movement of goods.[22] While doing so ensured a quick solution to the initial access problems and facilitated initial discussions, potentially serious longer-term consequences exist when embedding people affiliated with a party to the conflict within the humanitarian response. This decision created opportunities for real or perceived undue influence, bias and use of position to manipulate humanitarian operations for political or personal gain. In addition, it breached neutrality principles and potentially compromised the agency’s independence. This practice has continued and, according to some key informants, has grown within the humanitarian response to the point that all UN entities and INGOs have people affiliated with the armed Houthi movement within their personnel rosters.[23] These people, who often occupy positions of influence and key posts such as in procurement departments, security and access, are able to influence or have control over information affecting programming and the allocation of resources and supply contracts. Their roles provide access to internal discussions and information that can be used against staff members perceived to work against Houthi interests, or for personal reasons. Several UN and INGO staff members have seen visas revoked and denied.[24] Only MSF and ICRC had previously invested in building a rapport with the armed Houthi movement, which had already become the de facto authority on the ground in part of the north prior to 2015. These organizations had an established presence in Sa’ada governorate prior to the current crisis,[25] and they had developed working relationships with the armed Houthi movement. A 2016 MSF report noted that networking is often undervalued by emergency response practitioners fulfilling short-term objectives. However, it said that “for the ICRC and MSF, having good contacts and a solid analysis have been key to unlocking access.”[26] |

In 2016, a peer review by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) recommended that the Yemen response develop a systemwide coherent access strategy to create and maximize opportunities to deliver assistance. Specifically, the IASC recommended the response:

- identify approaches and strategies to engage with actors who could provide or influence access;

- implement a better-informed and coordinated approach to access;

- engage closely with authorities on the ground to more quickly address issues including access denials, diversion and interference

- engage more closely with authorities on both sides to approve visas, travel permits and clearances as well as to organize training for authorities on humanitarian issues and principles to create more understanding and a more enabling environment; and

- improve the distinction between UN humanitarian and political actors.[27]

To date, this strategy does not exist, though some efforts have been made recently.[28] One aspect that has seen progress is the community’s ability to track access impediments. By the end of 2019, for example, efforts to more consistently and comprehensively track access constraints were implemented for areas under the control of Houthi authorities. This has helped to improve understanding of the types and impacts of restrictions imposed and to quantify the impact of these restrictions.[29] Yet, while monitoring and reporting access impediments have improved, this has not translated into a strategy or practical measures to resolve the impediments.

Barring the improved tracking system, little progress has been made on the 2016 IASC recommendations. Multiple key informants confirmed negotiations remain largely ad-hoc, resulting in one-off agreements that lack real strategic meaning and have little effect on the longer term.[30] For example, after Houthi authorities repeatedly blocked truck movements in 2019, a UN task force was appointed to work out a collective strategy to mitigate the restrictions. The process quickly fell apart: the appointed chairperson was frequently (and then completely) absent, which was especially problematic because no one was authorized to take decisions in his absence; agencies were reluctant to share information on their individual negotiations with authorities about the release of trucks, including any concessions they may have made; and task force leaders never built a negotiating strategy around the issue. In addition, the task force refused to accept INGO truck blockages within its remit, focusing only on such incidents experienced by UN agencies.[31] Thus, no comprehensive solution was negotiated or applied with the Houthis. Outside of ICRC and MSF, only one INGO in Yemen spoken to in the course of the interviews had developed an access strategy and SOPs to deal with key negotiation points.[32] No UN agency has an established access strategy.

Small Choices, Big Consequences: Bad Practices in the Response

Any emergency humanitarian response faces dilemmas on how to combine quick response with accountability, quality and principles. It is often tempting during high pressure moments to pick the easier and quicker fixes to problems. Yet, as experienced aid workers know well, such choices can have long-lasting adverse consequences for the response and the aid recipients it needs to reach.

When the conflict escalated in 2015 and Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates began an air and ground campaign to push the armed Houthi movement out of Aden and restore President Hadi to power in Sana’a, the war was expected to last only a matter of weeks, based on Saudi assurances. Choices made at the beginning of the L3 emergency response were made in that light. Yet, those choices have handcuffed the response by putting in place practices that do not meet the minimum standards of a principled response. The principles of humanitarian action are clear: It is to be guided by neutrality, meaning it cannot support parties to the conflict, as well as independence from any actor’s objectives in areas of aid operations.[33] The next report, ‘A Principled Response: Neutrality and Politics,’ fully explores the compromising of response principles and its consequences.

Because the humanitarian response took over from a development program, the long-standing interlocutors and implementers for the response were line ministries within each sector, for example: the Ministry of Health for WHO, the Ministry of Water for UNICEF’s WASH programs, the Ministry of Education for WFP school-feeding programs and for UNICEF’s education activities, etc. These longstanding relationships and the practice of working through ministries were retained when the humanitarian response was established in 2015 through the lens of a short-term conflict. As a result, to date a significant portion of humanitarian activities continue to be implemented through ministries, especially through those controlled by the armed Houthi movement. Yemen is unique in being a humanitarian response in which an armed actor in opposition to a recognized government is used as a partner to implement a response.

This practice has had serious consequences for the integrity of the response and for humanitarians’ ability to work unimpeded in the field. For example, 34 percent[34] of food distributions in areas under the control of the Houthi authorities in 2019 were carried out by the Houthi-run Ministry of Education (MoE). (This was in addition to all school feeding programs, which are headed by the Houthi education minister, Yahia al-Houthi, the brother of Houthi leader Abdulmalek al-Houthi.) For this, the Houthi-controlled MoE was contracted and paid at least US$9.8 million in 2019 alone[35] as an implementing partner. From a principled point of view, using a party to the conflict to deliver aid and implement humanitarian services directly breaches the principles of neutrality and independence. In addition, not only is a party to the conflict implementing humanitarian activities, it also is receiving financial compensation for doing so. The humanitarian system is, therefore, directly providing financial resources to a party to the conflict, money which reasonably can be expected to be used to sustain the war effort that is affecting civilians on a daily basis.[36]

The problematic use of non-neutral authorities as implementing partners, especially when it comes to handing over relief items for direct distributions, was raised in 2017 by the UNOCHA-led Humanitarian Access Working Group (HAWG). Specific concerns around conflict of interest, the potential to jeopardize access negotiations in the long term, risk of diversion, the use of items to support a warring party and the breach of humanitarian principles (because assistance provided by authorities would render it non-humanitarian through association) were noted, among others.[37] Although it was recommended that authorities perceived as being party to the conflict should not be used as implementing partners to directly deliver assistance, unless as a last resort and with a clear exit strategy,[38] the practice remains commonplace.

In addition to this, the use of Houthi-run ministries has proven to be severely problematic. In 2019, for example, for one UN agency, more than one-third of all incidents recorded as operational interference, including interference in beneficiary selection and rotation and failing to meet minimum distribution standards, were directly attributed to the Houthi-controlled Education Ministry.[39] It also was responsible for almost one-quarter (23 percent) of all access incidents[40] recorded during the year, including appropriating food from distribution points, harassment of personnel and operational interference as described above.

The amount of diversion of humanitarian aid and interference in implementation directly related to the use of a party to the conflict as an implementer is significant and replicated in other sectors through other ministries and authorities. For example, SCMCHA continues to be in control of registering those eligible for emergency relief in areas under Houthi control,[41] UNICEF continues to disburse cash transfers through the Houthi-controlled Social Welfare Fund,[42] and the World Health Organization (WHO) overwhelmingly implements projects through the health ministries in both the north and south.[43] The problem is replicated to a lesser extent in the government-run south. For example, the Executive Unit for Internally Displaced Persons[44] has increasingly been trying to assert its authority within IDP camps in southern areas by determining activities and trying to take over their management.[45] But especially in areas under the control of Houthi authorities, those most responsible for imposing access impediments then present themselves as the solution in ways that allow them to directly benefit from the arrangement. As a result, the interference in humanitarian programming and activities is extensive and is to the detriment of the response. Ending this arrangement could jeopardize now-established relationships, a risk senior UN officials have been unwilling to take in an already difficult operating environment.[46] What seemed like a quick fix in 2015 has had long-term consequences on the integrity and effectiveness of the response to date.[47]

Key Decision Moment within the ResponseBeneficiary selection is a key element of any humanitarian response as it determines who is eligible to receive humanitarian assistance. Without the ability to correctly identify beneficiaries, the basis of any humanitarian response is flawed. It also relates directly to the ability of those in need to access humanitarian assistance. Selection criteria, adapted to context and put in place by organizations that provide the service, determine beneficiaries. These criteria aim to target the most vulnerable within communities, such as single-parent households, households with children suffering from malnutrition, displaced persons, the elderly or disabled, etc. Criteria also depend on available resources and access to the population. To ensure accuracy, accountability and to maintain independence, beneficiary selection is in theory controlled by humanitarian aid workers. In this way, factors including political affiliation, community power dynamics and corruption are designed to be distanced from aid distribution. To date, the response has failed to control beneficiary selection, especially in, but not limited to, areas under the control of Houthi authorities. In Yemen, humanitarian organizations accept lists of beneficiaries from authorities, from SCMCHA in the north and the Executive Unit in the south. While these lists are supposed to be verified, such a process for thousands of names, especially in emergency situations, would be an almost impossible task. Different UN agencies also often maintain their own lists. Attempts to cross-check lists among themselves for names of people receiving different services have often led to the discovery of discrepancies and duplications. In addition, the limited amount of time humanitarians spend on the ground and limited oversight make it difficult to know whether a beneficiary has been selected on the basis of vulnerability or because of other interests such as family connections or to secure loyalty. As a result, those most in need are often excluded from aid delivery. This was most recently evidenced by the Danish Refugee Council and Protection Cluster’s November 2020 report, which found that the most vulnerable — women, the elderly, displaced persons, the disabled and the Muhammasheen, a long-marginalized social class — are those most likely to be excluded from aid. The report found that a lack of accountability in registering and verifying beneficiary lists resulted in the exclusion of these groups, and it said that more than two-thirds of respondents throughout Yemen blamed local authorities to some extent for their inability to receive aid.[48] Attempts to change the practice have faced opposition, not only from the authorities themselves, but also from within the humanitarian community. For example, during the 2018 Hudaydah offensive, humanitarian agencies prepared to respond to those displaced by the fighting. Recognizing a moment to put in place appropriate and principled response systems, a joint UN and INGO push was made to gain access to displacement camps and to ensure verification of beneficiaries. Unfortunately, this attempt was blocked by senior humanitarian leadership in Yemen, which acquiesced to Houthi demands to undertake blanket cash distributions on the basis of lists provided by the authorities.[49] This decision further embedded control of beneficiary selection with local authorities which set a difficult precedent. Attempts to improve the beneficiary selection process in 2019 also failed to make much headway. Proposals were made by a UN agency to begin the process, including reclaiming control of registering beneficiaries from SCMCHA and other authorities.[50] Successful implementation, however, would have required the agreement of other agencies conducting registration for other sectors. Once again, there was little appetite within the rest of the humanitarian community to tackle the problem and engage in what would undoubtedly be a contentious and difficult negotiation, and a lack of support from senior leadership. A watered-down version of the proposal ultimately was passed by the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) that increased joint registration as well as oversight of beneficiary selection and registration rather than advancing an independent registration process. Though a step in the right direction, the measures still fall far short of globally accepted standards for beneficiary selection. |

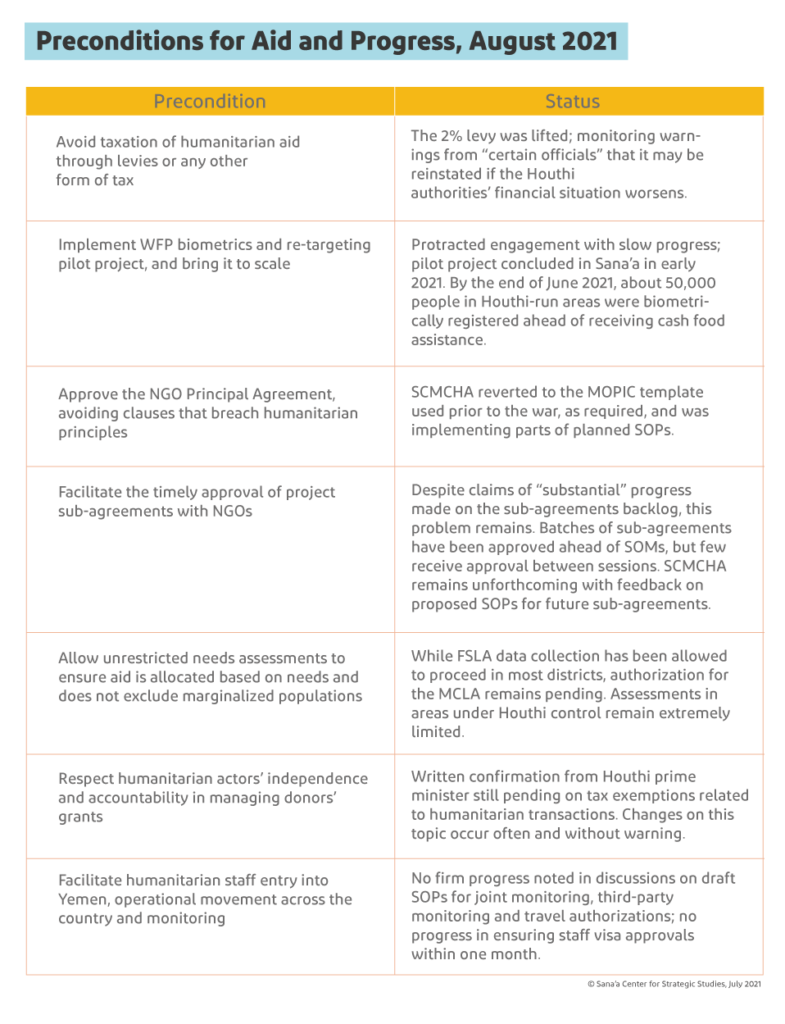

Pressed by Donors, Effort is Made to Establish an Access Strategy

Following a sharp deterioration in access in areas under the control of the armed Houthi movement in 2019, and threats from increasingly frustrated donors to cut or suspend their financial support over Houthi interference, the humanitarian community rallied to try to negotiate a way forward. This initiative produced the Senior Officials Meeting (SOM), the first session of which was held in February 2020. It resulted in a unified stance by the UN, INGOs and donors for the first time since the start of the response. As part of the SOM, seven preconditions were drawn up for Houthi authorities to meet to enable response, with 16 benchmarks identified to monitor progress toward meeting the conditions. Further funding and recalibration of programming were to be contingent on progress made. Benchmarks included the signing of sub-agreements with NGOs, authorization for the World Food Programme (WFP) biometric registration and re-targeting and establishment of SOPs for humanitarian movements.[51] Despite initial enthusiasm and some gains in key demands, the process is largely considered to have stalled (see Table 4.1).[52]

Aid workers involved in the process have pointed to a lack of understanding and expertise on how to build and implement a negotiation strategy as one of the reasons the process has not moved forward as hoped.[53] For example, nobody in the SOM process from the Yemen operation has, in practice, previously established or implemented a strategy for negotiating access. Limited technical input by experts has been taken into account and those with technical access experience in the response left in 2019 and early 2020. Those involved in the SOM process also continue to engage with the same actors with whom they have made little progress in past years; this is due to the lack of any comprehensive mapping of actors and spheres of influence, which will be discussed further below. As one aid worker pointed out, while the benchmarks track progress on the signing of sub-agreements and the establishment of an SOP for movements, progress on these benchmarks does not automatically translate into unimpeded access.[54] Even if SOPs are established and sub-agreements get signed allowing pending activities and programs to proceed, authorities can still reject travel permits and effectively halt all humanitarian movements and activities.

Table 4.1

Sources: Internal SOM document, September 2020; WFP; and key informant[55]

Sources: Internal SOM document, September 2020; WFP; and key informant[55]

While the SOM signaled for the first time an attempt to implement a unified system-wide response to a deeply constricted operating environment, it fell short of being a comprehensive operational and access strategy, making it unlikely to gain the results and impact needed to improve the operating space in Yemen for an effective response.[56]

Learning to Say Enough is Enough – Redlines Within the Response

Defining preconditions and benchmarks for humanitarian response constituted a rare attempt to set any boundaries, however mild, with authorities in Yemen. The pervasive inability and unwillingness to put in place system-wide operating principles to guide the response and to draw redlines has severely constricted the operational space. In the humanitarian community, redlines are defined as “actions or conditions deemed unacceptable by aid providers and beyond which they will not operate.”[57] Examples of redlines enforced in other global responses are extensive and include actions such as the looting and destruction of humanitarian compounds or the killing of aid workers. In some instances, redlines are set at the country level by the HCT, as for example, in South Sudan, Syria and Somalia,[58] but usually redlines are defined by individual agencies in line with their own risk tolerances. The crossing of redlines normally triggers consequences, and frequently results in the suspension of operations. For example, the killing of two guards and the arrest of a WFP security officer by national security officials in South Sudan led to the suspension of operations for several months in the affected location until national authorities pledged to ensure the safety and security of humanitarian staff members.[59]

In Yemen, instances of blockages, looting, diversion and harassment of humanitarian personnel are frequent and well documented. Yet in no other context are there fewer consequences for parties who continuously breach what would be considered redlines in other response contexts. As one INGO staff member said: “The Houthis put in place these crazy restrictions and yet we come to their rescue again and again. They block all our assessments, and we just go back to the international community and ask for more money. We know it gets diverted, but we just give in every time – in the name of the beneficiaries.” [60] This sentiment was echoed by several aid workers interviewed.[61]

Attempts to put in place parameters to safeguard operational space and define acceptable restrictions have been made but not implemented within the response. In 2016, the HCT formally adopted joint operating principles, which attempted to ensure a coordinated approach by humanitarian actors in line with the principles of humanity, neutrality, independence and impartiality.[62] INGOs simultaneously developed an “information-sharing guidance” document,[63] which clarified where to draw the line in sharing information when negotiating humanitarian access to avoid compromising humanitarian principles. For example, it was agreed that sensitive information such as beneficiary lists, inventory lists and staff contact lists should not be shared. The joint operating principles guided the response to, among other things, provide assistance based only on independent needs assessments, not share beneficiary information, not use armed escorts, pay taxes only when clear and legal procedures exist and to reject any request by authorities to accompany humanitarians during their work.[64] The agreement was never implemented, and many of the points the humanitarian community had stated it would not accept (for example, the use of armed escorts, interference in beneficiary selection and needs assessments, delivery of humanitarian assistance to parties of the conflict) are now common practice. In addition, most points regarding information-sharing redlines relate to information already readily available to, and shared, with authorities.

In May 2019, another attempt was made to put in place operational parameters through a Framework for Humanitarian Engagement.[65] The framework was much weaker than the 2016 version, breaching several minimum operating standards; for example, the document agreed to share beneficiary information with authorities unless it specifically related to protection, medical data or receiving cash assistance. This means that for any general distribution, people’s names, locations, origins and contact details can be shared with authorities. It also agreed to provide relevant organizational information to authorities in accordance with reporting agreements, while remaining vague about the sort of information that may include.[66] Adherence to most clauses remains poor, despite the watered-down parameters.[67] Continued acceptance of Houthi authorities’ conditions and behavior without consequences has failed to improve the deeply compromised and restricted operational space in Yemen.

Key Decision Moments within the ResponseTwo key moments in 2019 illustrate how redlines could have improved the humanitarian operating environment. In one instance, a redline was drawn but implemented badly; in another, an egregious attack on an aid worker was allowed to pass without consequences.

To date, the WFP suspension remains the only substantive instance in which humanitarian actors have attempted to put in place any consequences in response to a breach of humanitarian standards. |

Key informants often cited a lack of solidarity among humanitarian actors and the absence of a collective front and weak leadership for the reluctance to set and enforce redlines. Interviews with INGO staff indicated a paucity of cohesion among INGOs in terms of sharing information and addressing issues of mutual concern.[69] In addition, NGOs (both international and national) have reported perceiving a lack of solidarity from the UN when seeking support for issues they face.[70] This has been exacerbated by Houthi authorities’ decision early in the response to dissolve the NGO forum, a platform that had facilitated inter-NGO coordination and offered the possibility of presenting a united front to both the UN and authorities. In addition, a competitive culture for funding among UN agencies and INGOs can undermine solidarity. Such divisions within the community have undermined the ability to confront violations and negotiate coherently for better operational space. The propensity of UN entities to work with authorities and their use of ministries to implement activities has only added to an unwillingness to address key operational impediments for fear of jeopardizing relationships, regardless of the consequences.

Hard to Reach or Easier to Avoid?Responding to needs in complex conflicts or in countries with weaker infrastructure often poses additional challenges in accessing the populations in need. For that reason, many humanitarian operations (including in Iraq and Syria) work with a Hard to Reach (HTR) classification system, which monitors barriers to sustainable delivery.[71] The HTR methodology was put in place in Yemen in 2019, and, like the AMRF described above, it is used to understand and map access constraints nationwide. In the Yemen context, HTR refers specifically to the following access impediments alone or in combination.

The exercise, which is intended to be carried out biannually, has enabled the humanitarian community to track changes over time, and has provided data to substantiate the claim that the access environment in Yemen has deteriorated. In April 2019, for example, 5.1 million people in need living in 75 districts were classified as hard to reach.[73] By January 2020, this was estimated to have increased to 18 million people in need who were hard to reach,[74] and to 19.1 million in 222 districts by the end of 2020.[75] The majority of these increases were attributed to growing bureaucratic impediments in areas under the control of the Houthi authorities.[76] Though it serves an illustrative purpose, the tool does have flaws. One of the main problems with it is that the data collected is based on a qualitative rather than quantitative review of all 333 districts in Yemen. The classification system builds on results of access severity focus group discussions, which are held at hub levels with partners.[77] Therefore, it reflects perceptions of areas being hard to reach rather than presenting quantitative data to back up these statements.[78] Though intended to be supported by other data sets, such as analyses of clusters’ planned and achieved targets where an extensive gap could point to access constraints, the classification does not quantitatively measure access constraints. The picture painted by the classification also can be somewhat misleading. For example, the HTR classification is heavily weighted by bureaucratic restrictions imposed by central-level authorities in Sana’a rather than at the district level. Yet the classification does not reflect whether the source of the restrictions is at the central or district level. In addition, the results of the current classification put the majority of Yemenis (almost 80 percent of the population deemed in need of humanitarian assistance, living in 220 districts) as hard to reach.[79] This would mean that sustained programming and delivery of aid is compromised to the vast majority of those who need it. Yet, according to the HRP and the OCHA 3W map, organizations continue to claim ongoing delivery to an increasing number of beneficiaries.[80] It is unclear whether this disconnect is due to HTR being improperly represented or whether there are flaws in the response delivery data. There are certainly hard-to-reach, and even a few inaccessible, areas in Yemen. But, as some humanitarians interviewed noted, failing to acknowledge these areas as particularly challenging by not being more circumspect in applying the label of hard to reach does them a disservice.[81] In addition to the above, as pointed out by several humanitarian access practitioners, the mapping also lacks nuance and does not necessarily accurately reflect conditions in the country. Access is not the same for everyone, and restrictions are not applied uniformly. What is accessible for one sector, or some organizations, is not the same for others. For example, food distribution and health activities usually have more access than protection activities or organizations focusing on human rights. At times, international organizations may not have access, but local organizations do through local connections and community ties.[82] This brings into question for whom an area is being defined as “hard to reach.” The mapping also offers an excuse for inadequate implementation. Organizations and practitioners can use the HTR label to justify sub-standard implementation, or a failure to implement, with donors and authorities. HTR is not an absolute, but rather a sliding scale. The label does not measure the severity of access restrictions (for example, an area might be hard to reach, but this does not mean there is no access if continued attempts are made and resources are assigned to mitigate the impact of restrictions); HTR also is often read as “impossible to access,” providing an excuse to not attempt to access areas or find alternative ways for delivery.[83] Lastly, Yemen’s HTR classification is not accompanied by a strategy to mitigate or overcome the accessibility challenges. As with the majority of access restrictions in Yemen, while the problem can be and often is identified, the next steps to address the issues are often not discussed or taken; leaving the problem unaddressed can be easier and be used as an excuse to explain poor functioning of the response.[84] |

Know Who You are Talking To – The Failure of Negotiation in Yemen

One of the key gaps discussed in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Security’, was the security apparatus’ absence of capacity and expertise to collect information and analyze context, which is especially important in a country with localized tribal and clan dynamics as well as conflict and complicated political dynamics. This problem is not confined to the security sector but spills over into the operational and access part of the response. One of the greatest impediments to access in Yemen is that those within the humanitarian operation do not know to whom they should be speaking. The development of an access strategy also requires at least some analysis of actors and structures, both formal and informal. Actor network mapping helps to identify key interlocutors, their relationships, their points of leverage and their networks. Over time, through active networking and the development of relationships with interlocutors, key stakeholders can be identified for negotiation and advocacy. In most humanitarian operations, networks like these are built, maintained and expanded, and then leveraged when needed. A good example of this took place in South Sudan in 2013. The head of a UN entity in South Sudan at the time attended church in the same congregation as the wife of a senior government official. When the humanitarian operation faced restrictions on moving aid to Pibor, where an emergency was taking place in opposition territory, the relationship through the official’s wife was successfully used in efforts to gain access to the area in question. For the first time in the South Sudan response, a cross-line operation was successfully established, forming the baseline and model for cross-line movements in South Sudan until today.[85]

The humanitarian operation in Yemen lacks a comprehensive mapping of actors engaged in the conflict, including their networks and areas of influence, which limits the ability to negotiate access and defend humanitarian space.[86] On a daily basis, negotiations take place, including at senior levels, without fully understanding bases of power, actor networks and affiliations where indirect negotiation could create leverage. The January 2016 peer review of the Yemen humanitarian operation indicated early on that there was a need to identify approaches and strategies to engage with various actors — conflicting parties and local authorities as well as community, religious and business leaders — who could provide or influence access.[87] Still, it was only at the end of 2019 and through some initiatives undertaken in 2020, that efforts were made to understand the wider negotiating environment, which includes tribes and other local structures dispersed throughout the country with the ability to profoundly impact negotiations.[88] In southern Yemen, for example, buy-in from tribal authorities is considered key to establishing safe and sustained access to areas under their control.[89] In areas under the control of the Houthi authorities, it is important to understand the supervisor system and identify the correct supervisor as individual supervisors will ultimately be in charge of access for their areas.[90] In those cases, whether the official channels, such as SCMCHA in the north or Yemeni government bodies in the south, grant access will matter little if the informal channels will not. While the research described above fosters a wider understanding of negotiation dynamics and networks, such efforts instigated outside of the response have yet to make a dent in the marked lack of understanding of how to negotiate and with whom in Yemen.

The inability to identify the correct stakeholders can have far-reaching consequences. For example, had a comprehensive mapping of the authorities in Sana’a been available in June 2019, when WFP was negotiating with Houthi authorities for the beneficiary identification system or during the creation of SCMCHA later in 2019, negotiations may have been informed differently and achieved better results. This issue was identified as far back as 2016, when the humanitarian community found that the results of negotiations with the Houthi authorities at times had backfired as a result of incorrect identification of power holders.[91] An additional consequence of this practice was that it inadvertently empowered stakeholders who previously had little influence, adding yet another layer to any access negotiations.[92] Despite recognition of this shortcoming early on in the response, the same problem remains to date and is only exacerbated by the lack of presence in the field. Permanent staff presence across the country, and proximity to locations where services are delivered, is paramount to identifying stakeholders and facilitating negotiations.[93]

In addition, negotiations in Yemen are highly centralized in that they are generally carried out by either senior humanitarian leadership or heads of agencies with two or three designated authorities and no involvement or support from technical access staff. Involving such narrow pools of individuals limits leverage and maneuverability, resulting in standoffs. Furthermore, bigger agencies will also often engage in parallel negotiations without sharing information with other partners. Negotiating on an individual level without taking into account the wider system can often lead to compromises being made for quick gains, and it sets a bad precedent for other organizations coming after. For example, in 2019, one INGO signed a revised version of the principled agreement with Houthi authorities that included multiple clauses considered anathema to the response as a whole, such as not accepting UN funding and allowing significant interference in staff recruitment. This only complicated all other INGOs’ efforts to push back against such clauses.[94]

The centralization of negotiations has also had a wider impact, especially in Houthi-run territory. Focusing access negotiations at the Sana’a level has undermined the strategic importance of local authorities and members of communities that may benefit from humanitarian access. For example, on one occasion in 2019, an INGO at odds with central authorities faced expulsion from Hajjah; the dispute was settled and activities continued after intervention from the communities the group served, whose residents protested on the doorstep of the local authorities in Hajjah.[95] By focusing on negotiations with SCMCHA at the Sana’a level, the humanitarian community has effectively reinforced and empowered central authorities to act as gatekeepers and has disempowered communities, tribes and local authorities.[96]

The Lack of Presence and Operational Culture

A 2014 MSF critique of the humanitarian system as a whole pointed out a troubling tendency among humanitarian organizations in crises worldwide to act more as technical advisers and supervisors than as implementers.[97] This tendency to work from a distance through proxies was noted as a key problem in Yemen by several people interviewed in the course of this research.[98] The UN in particular has extremely limited field presence, with the majority of its staff in Sana’a and Aden, and a very limited presence in field hubs (see: ‘A Centralized Response is a Slow, Ineffective Response’). One of the INGO actors interviewed put it bluntly: “The UN are not in the field; we rarely ever see them. They have no clue what is happening in this country.” [99]

There are various reasons for lack of presence, including security management, which was discussed at length in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Security.’ Another reason relates to operational culture. Yemen, in the context of humanitarian operations, is one of the more comfortable duty stations. Accommodations in Sana’a, and even Aden and most field hubs, far surpass standards of comfort in other responses, where hot water, comfortable apartments, air conditioning, and access to restaurants and shops cannot be taken for granted. In addition, rest and recuperation cycles in Yemen are frequent, with one week off every four weeks in-country for the UN, and every six to eight weeks for most INGOs. A lethargy within the operation has resulted, with staff largely remaining in comfortable, fortified compounds and waiting for regular breaks outside of the country. Access negotiations, however, take time, effort and energy. Accessing areas outside of well-established bases requires planning, a mountain of bureaucracy, internal negotiations, external negotiations and reducing comfort levels. With little external pressure to move out of comfort zones, the operational culture within the Yemen response is beset by indolence. A UN staff member based in areas controlled by the internationally recognized Yemeni government said it was difficult to get international UN staff to leave the UN enclave in Aden for missions and almost impossible to persuade UN Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS) security officers, who would be expected to accompany them at least once to facilitate security clearances.[100]

This problem is exacerbated because although an L3 emergency declaration is intended to mobilize, among other things, the right skillset and staff, this has not been the case in Yemen. Multiple interviewees indicated that the Yemen response lacks experienced emergency and operational personnel as well as those with specialized technical skills.[101] Furthermore, an insufficient proportion of the humanitarian personnel working within the response are committed to ensuring it succeeds, according to key informants who directly linked this to a stagnation of operational response and an inability to drive forward and improve. This situation also has led to burnout and rapid turnover of the qualified staff operating in Yemen who, in a better work environment and with more senior support, would be capable of raising the level of the response.[102]

Within the access sector specifically, despite the numerous challenges and declining environment, there was until late 2018 only one international staff member on the ground dedicated to access issues. By the start of 2019, four international access staff had been added across three UN organizations, bringing in additional capacity and experience in operational access.[103] However, rather than capitalize on the newly available critical mass of capacity and expertise within the response, these persons were largely centralized and office bound in Sana’a and Aden with little ability to improve access or the operational environment. As a result, the focus remained largely on the more bureaucratic aspects of access (both within and outside of the system), and on information management related to access impediments. Furthermore, bringing in access personnel resulted in internal battles over field presence and security, which diminished efforts to improve the presence of the response where it was needed. By the end of 2019, internal and external disinterest in making an improved field presence possible led to the exit of most of the access expertise and capacity from Yemen.[104] As of mid-2021, the Yemen response was back in the same situation as it was prior to 2019, with only one international UN staff member dedicated to access on the ground.[105]

Viewing Access as a Challenge, Not an Impossibility

Access is key to establishing and maintaining a well-functioning humanitarian response. Without access, humanitarians are unable to stay and deliver. Although critical, it is also one of the most fundamental problems of the Yemen response. Yemen is claimed to be one of the most challenging contexts in terms of humanitarian access, yet there has been no corresponding investment in overcoming this challenge. There has not been a system-wide access strategy since the start of the L3 emergency response in 2015. Technical support for access in the country is extremely limited, and when this technical support was more widely available, it was not used wisely; more energy was spent frustrating the extra capacity available than utilising it. Access officers are used widely in other contexts; their absence in Yemen is significant.

Not only does the response have no access strategy, it also is increasingly boxed into a narrow negotiating space because it has centralized decision-making power over operations and access in Sana’a and Aden. In the north, all negotiations take place in Sana’a with just a handful of interlocutors. This gives immeasurable power to few individuals, with far-reaching consequences for the whole response. It also means there is only one level of negotiation: the top. If this level fails, or deadlocks as it so frequently has, little room remains for negotiation and leverage. This has disempowered the local levels of authorities and community leaders who previously had a say, and often still wield significant leverage. Part of the problem lies in the lack of understanding of the Houthi administrative structure, the key actors, power networks and spheres of influence. This gap handcuffs the response to a few channels, which have increasingly been able to bend the response to their will.

The response in Yemen also has a history of accepting bad practices and crossing redlines. Standards upheld in other contexts are dispensable in Yemen. Implementation of activities is done by parties to the conflict. Arrests of national staff by security offices are regular, and prolonged detention of international staff also has passed with little comment or reaction. Consistent interference, diversion and manipulation is widely documented and public, but the response’s senior leadership has been unwilling to take a stance that might provoke authorities who are implementing activities and hold power over visas. Continuous acquiescence, however, has not led to improvements but rather ever-increasing demands — and less access.

Access in Yemen is also often used to manipulate information and data. While most organizations claim to have reached between tens of thousands and millions of people, the vast majority of access to those who benefit from humanitarian response is not by humanitarians themselves, but through authorities and parties to the conflict. Access is therefore not neutral or impartial, but highly dependent on those with interest in where aid ends up. It also often remains unclear what is meant by the number of people reached. Is humanitarian assistance reaching people once? Or in a sustainable manner that actually improves people’s condition? What assistance is reaching people in need and what is not?

On the other hand, access, and more specifically access constraints, are often used as excuses to justify poor implementation, a lack of oversight and delays in delivery. If someone asks any humanitarian in Sana’a or Aden, “why have you not been to X location?” the response will be that this is because it is hard to reach. According to the official UN classification, two-thirds of the country’s districts are hard to reach. But many NGOs, and even the author, have managed to get to places that are considered to be hard to reach. Experience found that an ingrained preconception that a location was hard to reach, and the internal bureaucracy required to make the effort, proved greater obstacles than any encountered actually getting to the location. Most places in Yemen are not hard to reach. They just have challenges that require some time and effort to manage. Reaching somewhere the first time is always the most difficult. It is often less hard to go back the second time, and the third … until it becomes the new normal.

Painting an overwhelming picture of inaccessibility leads to little impetus to try. Why invest energy when it is easier and more comfortable to sit in offices and fortified compounds with a generous R&R cycle? Access requires time, dedication and effort. Disrupting that process every few weeks does not make for efficient progress. The picture painted also does a disservice to locations that are, indeed, hard to reach. If a better classification of hard to reach was available, with a more accurate view of the challenges, time and effort could be focused on the truly complex areas while aid moved more routinely as needed in the rest of the 220 districts said to be hard to reach.

The response also does a disservice to its potential, and to people in need in southern Yemen, by underutilizing the existing potential to operate in areas under the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government. The overwhelming majority of effort and attention go to Houthi-controlled territories, where attempts to open access have been hitting a wall for years. Yet the south, despite its more conducive operating environment providing the flexibility needed to move around, is neglected, and the opportunity to significantly impact those the response can actually reach is lost.

Redrawing a conducive operating environment that ensures principled, sustainable and effective access starts with establishing boundaries. If the response clearly sets out what it will and will not accept, there will be initial growing pains. Doing so will most likely lead to more restrictions. It will likely initially mean loss of visas in the north. It will mean antagonism and difficult conversations. But as technical access people will advise, authorities have more to lose than the response. An often-heard excuse for failing to correct the course of the response by enforcing redlines is that doing so will harm beneficiaries. It might. But the Yemen response already is causing harm through its current modalities and the lack of access to enforce a proper response; it struggles to understand, realistically, how many beneficiaries are receiving assistance and how reliant they are on it. This lack of control also plays directly into the potential for diversion away from need and toward a war economy. The question is whether the response will choose short-term pain for a long-term gain, or the other way around.

Recommendations

To Senior Leaders of the Yemen Humanitarian Response:

- To ensure aid is not being used to support continuing conflict:

- End the use of parties to the conflict as implementing partners; and

- establish concrete consequences for authorities when they act outside of reasonable, globally accepted standards (on interference, manipulation, diversion, etc.). These may include, for example, withholding institutional support from the authorities involved, suspending aid temporarily in areas where breaches have occurred and communicating breaches to donors and the public.

- Act as one body, showing solidarity and cohesion to external parties, ensuring no organization acts on its own to undermine joint positioning and negotiations.

- To improve the access environment in Yemen:

- prioritize establishment of a system-wide access strategy developed by people with expertise in access strategies and those with sound operational experience;

- undertake a full stakeholder and network analysis of authorities and groups in Yemen to identify a broader network of actors with whom to advocate for and negotiate on key humanitarian issues;

- clearly define redlines for the response as a whole and the consequences for crossing them. If redlines are crossed, the stated consequences must follow. All organizations must adhere to the redlines set to ensure maximum leverage and enforcement capacity;

- prioritize support for operational access over reporting of access impediments; and

- put in place clear guidance on appropriate behaviour for humanitarian actors which all organizations must adhere to (such as the humanitarian framework or joint operating principles as discussed above). UNOCHA should monitor this adherence on behalf of the humanitarian community.

- Invest in proper technical expertise for the Yemen mission, and empower these staff members by providing the space, resources and support needed to improve the operational culture.

- Hire access staff who have experience with complex environments and operational challenges as well as a track record of paving the way for improved response, and permanently deploy them to access hotspots to negotiate on the ground with authorities.

- Invest in adding expertise from different channels (e.g. academics with Yemeni backgrounds or in depth experience in Yemen who have good knowledge of authorities and power structures) to advise on access strategies, networking, actor mapping and power dynamics to better tailor response and strategies. This can help in identifying a wider network of secondary actors with pathways to those in power that could be leveraged.

- Shift staff from Sana’a and Aden into the field, and ensure objectives and goals focus on improving aid delivery rather than reporting.

- Differentiate between areas under the control of Houthi authorities and those under the internationally recognized Yemeni government, and take advantage of the better operational space and access in southern areas to mount a quality and effective response that will make a sustainable difference for many people.

- Base R&R cycles on actual workload, risk-related stress and living conditions to maintain staff well-being while ensuring a more consistent staff presence in Yemen.

To All Humanitarian Sector Actors within the Yemen Response:

- Improve understanding of access at all levels and ensure acceptance of activities by way of the following:

- Provide quality and appropriate activities that are delivered in an independent and neutral manner; and

- build understanding of (power) dynamics and context from the local level up, and develop networks that can provide leverage upward.

- To improve the beneficiary selection process:

- Ensure neutral and independent verification of the beneficiary selection process. Do this by providing organizational monitors and prohibiting subcontracting to a party to the conflict with a vested interest in where aid ends up.

- Prioritize solidarity within the humanitarian sector to ensure redlines are upheld and one organization cannot undermine another. This can be done by drawing up a clear document outlining redlines and transparently sharing it within the community. Any organization’s breach of the redlines should be reported to senior leadership and donors, and issues should be transparently discussed.

- Data reflective of the situation on the ground should be used to enable analysis that will better inform access decision-making. In particular:

- The hard-to-reach classification should be revised to nuance the concept of hard to reach, be based on solid data rather than subjective perceptions emanating from focus group discussions, and ensure that areas considered hard to reach are actually hard to reach; and

- Access constraints should be reported in a transparent, consistent and timely manner to ensure trends and problems are able to be identified through analysis in a timely manner and addressed.

- An access hotline should be established by UNOCHA to immediately deal with access issues as they are reported in a principled and consistent manner.

- Improve programming and presence in areas of need where the operational environment is more permissive, which in practical terms would improve the quality of the response in the south. The failure to establish solid parameters and a functional working environment in Houthi-controlled northern areas and the leadership focus in and on Sana’a should not be allowed to impact aid elsewhere.

To Donors:

- Stop funding organizations who use parties to the conflict as implementing partners.

- Demand a more accurate and evidenced analysis of “hard-to-reach” areas, ensuring the classification is not being used to detract attention from poor program implementation.

- Support the humanitarian community in developing and maintaining redlines by introducing funding consequences for organizations that do not uphold them.

- Build flexible modalities into funding agreements to support the temporary suspension and retargeting of aid, if necessary, to enable the humanitarian community to institute and uphold consequences of redline breaches.

- Provide the Yemen response and its senior leadership with adequate support as a donor bloc, which would assist in the drawing up and implementation of redlines and their consequences.

Up Next in this series of reports examining fundamental issues of concern in the Yemen humanitarian response is ‘A Principled Response: Neutrality and Politics’, which considers the far-reaching consequences of allowing flaws in the response and the intertwining of aid and politics to erode the fundamental guiding principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security-related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

This report is part of the Sana’a Center project Monitoring Humanitarian Aid and its Micro and Macroeconomic Effects in Yemen, funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. The project explores the processes and modalities used to deliver aid in Yemen, identifies mechanisms to improve their efficiency and impact, and advocates for increased transparency and efficiency in aid delivery.

The views and information contained in this report are not representative of the Government of Switzerland, which holds no responsibility for the information included in this report. The views participants expressed in this report are their own and are not intended to represent the views of the Sana’a Center.

- See, for example, “Access. Humanitarians are unable to reach millions of people who need help to survive,” UNOCHA, November 4, 2019, https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/yemen/card/43I17TvF8t/

- “Global Humanitarian Overview 2021. Yemen,” UNOCHA, December 1, 2021, https://gho.unocha.org/yemen

- Administrative impediments can include visa denials, registration requirements with conditions that run counter to humanitarian principles and best practices, illegal taxation, bribery; operational hindrances include, for example, denying entry to an area, interfering with the registration and rotation of beneficiaries, threatening aid workers or seizing food aid and other assets, including vehicles.

- These are the Access Monitoring and Reporting Framework (AMRF), as well as two tools that are discussed below, the Humanitarian Access Severity tool and the Hard to Reach classification system. Like all tools they have some limitations: They are highly dependent on reporting, and the access severity tool is highly subjective as it is based on people’s perceptions of access rather than data.

- See, for example: “Yemen: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (January – February 2021),” UNOCHA, Sana´a, April 11, 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-access-snapshot-january-february-2021

- “Access Monitoring and Reporting Framework,” UNOCHA, New York, 2012, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/OCHA_Access_Monitoring_and_Reporting_Framework_OCHA_revised_May2012.pdf

- “Yemen: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (2019 Yearly Overview),” UNOCHA, Sana’a, April 23, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-access-snapshot-2019-yearly-overview; “Yemen: Annual Humanitarian Access Overview 2020,” UNOCHA, Sana’a, March 14, 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-annual-humanitarian-access-overview-2020

- “Yemen: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (2019 Yearly Overview).”

- Interviews with senior UN expert, November 5, 2020, and senior humanitarian analyst, November 17, 2020; “Yemen: Sa’ada Humanitarian Needs and Response 2012,” UNOCHA, Sana’a, December 31, 2012, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/Sa%E2%80%99adah-Humanitarian-Needs-and-Response-2012-as-of-31-Dec-2012_0.pdf

- “Critical Impediments to Humanitarian Access in Yemen,” confidential INGO joint analysis paper shared with the author in 2020, dated September 4, 2016, pp. 2-5.

- “Yemen: Annual Humanitarian Access Overview 2020.”

- “Yemen: Humanitarian Access Severity Overview,” UNOCHA, January 2019, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/ocha_yemen_humanitarian_access_severity_overview_jan_2019.pdf; Maggie Michael, “UN Food Agency Says Aid Looted in Yemen’s Houthi-held Area,” January 28, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/4302168b612e6b1f77d1b77f62e85fcf; “Yemen: US to stop aid in Houthi areas if rebels do not cooperate,” Al Jazeera, February 25, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/2/25/yemen-us-to-stop-aid-in-houthi-areas-if-rebels-do-not-cooperate; information on Houthi authorities’ obstruction of humanitarian assistance has been included annually in final reports to the UN Security Council by the UN Panel of Experts’ 2140 Sanctions Committee (Yemen), and are accessible at, https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/2140/panel-of-experts/work-and-mandate/reports

- “Yemen: Mid-Year Review, Humanitarian Response Plan 2010,” UNOCHA, Sana’a, 2010, pp. 1-3.

- Interviews with INGO staff members #3 on November 14, 2020, #4 on November 16, 2020, and #7 on November 20, 2020; senior humanitarian analyst, November 17, 2020; and donor #3, December 14, 2020.

- Interviews with senior UN expert, November 5, 2020; UN staff member #5, December 15, 2020; and INGO staff member #7, November 20, 2020.

- Interviews with INGO staff members #3 on November 14, 2020, #4 on November 16, 2020, and #7 on November 20, 2020; UN senior staff member #2, November 13 and 27, 2020; and UN agency staff member #5, December 8, 2020.

- Sub-agreements are the framework upon which NGOs operate in government- and Houthi-controlled territories in Yemen. Signed by authorities, they permit organizations to implement projects where specified.

- Interviews with INGO staff member #1, November 5, 2020; INGO staff members #4, #5 and #6, November 16, 2020; UN agency staff member #1, November 13, 2020; UN senior staff member #1, November 13, 2020; UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN staff member #3, December 2, 2020; UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; and UN staff member #4, December 9, 2020.

- Interview with INGO staff member #1, November 5, 2020; UN agency staff member #1, November 13, 2020; UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; and UN staff member #4, December 13, 2020.

- Interview with INGO staff member #5 on November 16, 2020.

- Interviews with senior UN expert, November 5, 2020; senior humanitarian analyst, November 17, 2020; and UN staff member #5, December 15, 2020.

- Interview with UN staff member #5, December 15, 2020.

- Interviews with UN senior expert, November 5, 2020; UN staff member #1, November 12, 2020; UN agency staff member #1, November 13, 2020; senior UN staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; UN staff member #4, December 9, 2020; UN staff member #5, December 15, 2020; INGO staff members #7, November 20, 2020, and #10, December 3, 2020; and senior political analyst, November 11, 2020.

- Author’s experience in Yemen in 2019; interviews with UN senior expert, November 5, 2020; UN agency staff member #1, November 13, 2020; UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN agency staff members #3 and #4, December 7, 2020; UN staff member #4, December 9, 2020; UN staff member #6, December18, 2020; and INGO staff members #7, November 20, 2020, and #10, December 3, 2020.

- MSF was present in a non-permanent form from 1998 to 2007, when it established permanent presence. ICRC has been present in Yemen since 1962.

- Andrew Cunningham, “Case Study: Enablers and Obstacles to Aid Delivery: Yemen Crisis 2015,” MSF, May 2016, p. 11, https://arhp.msf.es/sites/default/files/Case-Study-01.pdf

- Panos Moumtzis, Kate Halff, Zlatan Milišić and Roberto Mignone, “Operational Peer Review, Response to the Yemen Crisis,” Inter-Agency Standing Committee, January 26, 2016, p. 7, 24-25.

- Interviews with INGO staff members #5, November 16, 2020, and #10, December 3, 2020; and UN staff member #1, November 13, 2020, and #3, December 2, 2020.

- For example, a mid-2020 UNOCHA assessment of access issues specified at least 163 interference incidents, primarily relating to delays or rejections of sub-agreements on NGO projects. It was able to note that, for this reason, 95 NGO projects with a cumulative budget of US$204.5 million and targeting up to 5.6 million people remained at least partly unimplemented. See: “Yemen: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (May – June 2020),” UNOCHA, Sana’a, August 24, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-access-snapshot-may-june-2020

- Interviews with UN staff member #1, November 12, 2020; UN agency staff member #1, November 13, 2020; UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN staff member #3, December 2, 2020; UN agency staff members #4, December 7, 2020, and #5, December 8, 2020; UN staff member #4, December 9, 2020; interviews with INGO staff members #2, on November 13, 2020, #5 on November 16, 2020, and #10 on December 3, 2020; and with INGO humanitarian adviser, November 18, 2020, and humanitarian analyst #2, December 15, 2020.

- Interviews with UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020, and UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020. Note: the author served on the task force.

- Interview with INGO staff member #10 on December 3, 2020.

- “OCHA on Message: Humanitarian Principles,” UNOCHA, April 2010, https://www.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/OOM_HumPrinciple_English.pdf

- “Expert Mission Report – WFP Yemen Operations,” WFP (internal report shared with the author during the course of the research in 2020), Rome, February 15, 2019, p. 6. The report indicated that the Houthi-run MoE had been handling more than 54 percent of the total general food distribution caseload in the areas under the control of Houthi authorities by 2017.

- “DFA Support Matrix_v9,” internal UN document seen by the author in 2019 and shared with the author by a key informant during the research period in 2020.

- A differentiation must be made between using parties to the conflict to implement humanitarian aid and paying incentives to certain government employees, such as health workers, or providing structural investment such as support provided to the Ministry of Water for the maintenance of water networks. These payments fall under support to vital services, which are necessary to ensure service delivery and safeguard essential infrastructure that humanitarian actors are not meant to replace. These initiatives are usually backed by development-oriented donors such as the World Bank and the UN Development Programme (UNDP), which have specific mandates to support these programs.

- “Risks associated with the use of non-neutral local authorities as implementing partners. Final Draft,” HAWG, Sana’a, (internal document shared with and seen by author in 2021), June 2017, pp. 1-3.

- Ibid., pp.3-4.