Introduction

On paper, Yemen is a principled humanitarian response, much like any other. Strategic documents from the past six years set out frameworks and codes of conduct that clearly reference the four fundamental principles that guide any response: humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence as well as the principle of first do no harm. While the words exist on paper, they are far less evident in practice.

Inconsistencies that chip away at these guiding principles have been cited throughout this series of reports. Neutrality has been undermined through the detailed information passed to the Saudi-led military coalition through deconfliction requests as well as through the deconfliction of ministries in Sana’a and the use of armed escorts. The use of parties to the conflict to implement humanitarian activities has undermined not only the impartiality of the humanitarian response but also its independence. Further diminishing that independence have been the failure to implement the Joint Operating Principles that were devised in 2016[1] and an acceptance of restrictions on needs assessments. Instead, the response has relied on authorities who have their own interests and agendas as key sources of information on needs and in identifying beneficiaries. Together, these factors call into question whether the Yemen response is still a principled response, or if it ever was.[2]

In an ideal world, delivering aid should not require compromising on core principles. Challenges on the ground, however, frequently lead to debates and decisions on whether and to what extent neutrality and independence can be compromised to ensure the delivery of aid. As such, compromising can become the norm rather than the exception, slowly eroding the foundation of humanitarian response. The consequences of this erosion can be far reaching.

If, for example, humanitarian organizations are no longer perceived to be neutral and independent, acceptance by parties to a conflict or even communities being served can decrease greatly – directly impacting the safety and security of aid workers and the ability to deliver assistance. This was seen in Darfur where mixing political and humanitarian advocacy with political and military choices led to increased attacks on humanitarian organizations on the ground.[3] Being seen to be on a certain side during a conflict can also lead to outright rejection of an organization in the future once realities on the ground change. This experience has confronted organizations in Afghanistan and Iraq.[4] Perceptions are also hard to change once established, and reputational damage can take decades to recover.

This problem has been influenced in Yemen through the uncomfortable intertwining of aid and politics. Aid decisions have, at times, been made to serve as cover for a lack of political progress in Yemen rather than for humanitarian reasons. Some key informants interviewed in the course of this research also raised concerns that not enough analysis has been done by the response in Yemen to evaluate the unintended consequences of the huge influx of humanitarian resources (financial and material) into the country, and that this assistance might be providing the means for at least one of the parties to the conflict to continue the war.[5] If this is true, the question has to be asked whether choices made in operating modalities contribute to this and whether the response is veering toward doing more harm to the population than good.

Humanitarian Principles and Their Practical Relevance

The Humanitarian PrinciplesHumanity: Human suffering must be addressed wherever it is found. The purpose of humanitarian action is to protect life and health and ensure respect for human beings. Neutrality: Humanitarian actors must not take sides in hostilities or engage in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature. Impartiality: Humanitarian action must be carried out on the basis of need alone, giving priority to the most urgent cases of distress and making no distinctions on the basis of nationality, race, gender, religious belief, class or political opinions. Independence: Humanitarian action must be autonomous from the political, economic, military or other objectives that any actor may hold with regard to areas where humanitarian action is being implemented. — OCHA on Message[10] |

Four key principles — humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence — form the foundation of any humanitarian action. They were developed from core values that have guided the work of the International Committee for the Red Cross and the broader Red Cross and Red Crescent movement since their establishment.[6] The principles were formally endorsed by the UN General Assembly in Resolutions 46/182 (1991),[7] and 58/114 (2004),[8] and are widely recognized throughout the humanitarian system. Their application not only guides and underpins humanitarian action, it also distinguishes humanitarian aid from other activities, such as those of a political, religious, ideological or military nature.[9]

One of the most fundamental debates in the humanitarian community centers around the hierarchy of these four principles and whether it is acceptable to compromise any of them to achieve the end goal of relieving suffering, preserving life and addressing needs. As such, the principle of humanity is not just a principle, it also defines the end objective of delivering humanitarian assistance.

In addition to these four principles, humanitarians adopted from medical ethics the concept of “first do no harm” and have applied it to humanitarian assistance since the 1990s. Its intent is to ensure that any negative or potential unintended effects resulting from aid delivery are considered before implementation. The objective of aid is to do good, not put communities in need at further risk. Unintended consequences can include making civilians more vulnerable to attack if they are perceived to have access to scarce resources, providing an advantage to a warring party or disrupting the local economy or individuals’ livelihoods.[11]

Finding a Balance: Principles vs. The Need to Deliver

One hundred percent adherence to principles throughout a humanitarian response is a gold standard that is often difficult to achieve. The politicization of aid, security concerns, diverse sets of assertive state and non-state actors in complex and protracted conflict situations are some reasons why principled humanitarian action is challenging. As a result, humanitarians often wrestle with inherent conflict between the ideal and an operational reality. For example: How neutral can and should one remain in the face of evidence of gross human rights abuses, knowing that speaking out could lead to loss of access to deliver aid? When negotiating for service delivery, is it acceptable to deliver aid to communities in less need if doing so will gain favor with authorities and result in access to high-need areas that are otherwise beyond reach? Should subcontracted service delivery be allowed through partners known to disregard humanitarian standards in exchange for access to hard-to-reach locations with high need? To what level is diversion tolerable if it ensures the rest of the aid will get to where it needs to go?

In reality, these sorts of dilemmas are faced constantly and highlight the need for pragmatic solutions that find a balance between upholding the principles of humanitarian aid while finding a way to meet humanitarian needs. Every humanitarian makes choices affecting this balance at some point. Ideally, the best solution would be for humanitarian organizations to perform better, design better operations and have skilled and professional staff handling these dilemmas in a principled manner. The compromises made, however, are often efforts to compensate for failures in humanitarian operations. The question then centers around finding the least-worst choice going forward without causing further harm.

Principle vs. Reality: Compromising in the Name of Humanity

Whether a response is principled can be subject to debate. As indicated above, principles are often viewed in a hierarchical manner. A perspective heavily favored by the senior humanitarian leadership in Yemen is that humanity — the imperative to alleviate suffering — trumps all other principles.[12] Those who support this view take the stance that it is acceptable to put aside independence, impartiality and neutrality as long as doing so achieves the goal of alleviating suffering.

There are contexts in which compromise for the sake of humanity is necessary and justified, and the humanitarian sector has developed guidance that offers a framework for these types of situations. Compromises are generally accepted when they fulfill the criteria of “last resort.” To be recognised as a last resort, the following criteria must be fulfilled: An overwhelming or critical humanitarian need must exist; there is no other viable alternative; and the compromise will be temporary and include a clear exit strategy.[13] In such cases, compromising to achieve humanity is accepted.

Last resort was correctly applied during the 2016–2017 Battle of Mosul, for example. As Mosul was liberated, heavy fighting took place, injuring not only combatants but also civilians, thousands of whom had remained trapped in the city. Taking into account the security risk, no organizations were willing or able to operate close to the front lines. As a result, medical transportation to the nearest humanitarian facilities able to treat wounded civilians was more than 80 kilometers away and would take hours, requiring passage through dozens of checkpoints. To offset this, the World Health Organization (WHO) coordinated support through various medical services for the trauma response, including a for-profit private company, Australia-based Aspen Medical, and non-profit organizations[14] whose personnel worked alongside Iraqi military medics. Their use was controversial; to enable access to the frontline in order to provide trauma response on a 24-hour basis, these organizations were embedded, or co-located, with the Iraqi military. Such a close alliance with one side to the conflict to deliver aid and the use of military and defense assets undermined the neutrality and independence of the response and associated organizations. Aspen Medical also used armed guards to protect its hospital as a risk mitigation measurement, detracting from any humanitarian character.[15] Yet, these various entities treated approximately 20,000 persons[16] in the course of nine months for conflict and trauma-related injuries. In this case, compromising on neutrality and independence, sanctioned under the premise of last resort,[17] saved hundreds of lives.[18]

The case of Mosul is a good example of how compromising to save lives can and should be done. It fulfilled the criteria of last resort:[19]

- A clear need and humanitarian imperative existed given the large number of civilians trapped in the city;

- there was no alternative. Other humanitarian organizations, including Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), had tried and failed to establish response close enough to the frontline to handle trauma cases;

- the service itself remained civilian in nature with civilian personnel undertaking the trauma response; and

- the intervention was time-bound in nature, being fixed to the duration of a single battle, and had an exit strategy. The battle lasted more than nine months, but as more of the city was liberated and the security situation improved, humanitarian organizations began to take over again; working under the protection of the Iraqi military was no longer necessary or done.

In Yemen, the argument of humanity and justification for compromise cannot be made in the same way. The response has continued for nearly seven years, but its modalities lost any temporary nature long ago; they are the norm, though they are not consistent with standards and best practice. Compromises have been made time and again with no real gain. By compromising on independence in establishing needs and implementation, the response remains unable to ensure that the most vulnerable are included in assistance.[20] It continues to compromise on standards and to directly fund authorities and government institutions, those controlled by the Houthis and the internationally recognized government, yet operational space keeps shrinking and access to communities decreases.[21] The risk of indefinitely putting the principle of humanity first at the expense of independence, neutrality and impartiality — and with little benefit — is ending up with a deeply unprincipled response that does more harm than good.

How far the balance has fallen to the unprincipled side in Yemen was illustrated in the events of late 2018 and 2019 in Durayhimi City.

Key Decision Moment in the Response: Aiding Durayhimi CityIn late 2018, Houthi authorities began to request humanitarian assistance to Durayhimi city, which they controlled, claiming thousands of civilians were on the brink of starvation.[22] Troops affiliated with the internationally recognized Yemeni government and UAE-affiliated forces had cut off access to the city in June 2018 as they positioned themselves for an assault intended to ultimately oust the Houthis from Hudaydah and its strategic port, 20 kilometers north of Durayhimi city.[23] A first delivery of food, water and basic hygiene products[24] was made to the city in May 2019 (this delivery was made without humanitarian presence on the ground to supervise its end destination[25]); in October 2019, WFP brought through a second shipment,[26] followed by another mission about two months later by the ICRC. The decisions to authorize repeated aid deliveries led to heated debates among agency senior management and operational aid workers on whether the acquiescence was too much of a compromise for the benefit it brought. Most residents had already fled what prior to the 2018 crisis had been the main city in a district of approximately 82,000.[27] Consultations with authorities and residents of the district as well as members of organizations that had managed to keep some contact with those on the inside made clear that Durayhimi city was highly militarized at the time with minimal civilian presence. Best estimates based on figures from an organization operating on the West Coast put the number of civilians in the city at fewer than 100, with one count indicating only 49 civilians; the rest were armed Houthi fighters and combatants they had taken as prisoners of war.[28] The remaining civilians, however, were thought to be in an extremely vulnerable position. Civilians were prohibited from leaving the city and prevented from communicating with the outside world. The understanding was that they were being kept as human shields by the Houthi forces inside to stop any Yemeni government attempt to take over the location. Any civilian trying to escape reportedly was shot by Houthi armed forces.[29] The humanitarian situation inside was considered likely to be poor. Considering the highly militarized context, the presence of prisoners of war and the specific and complex protection concerns for the few civilians remaining, the initial debate centered around organization mandate. The ICRC is clearly mandated and best positioned to intervene in such situations; the UN system and its agencies are less equipped and lack the technical expertise to handle the particular complexities.[30] The ICRC had opened communication with all parties around the matter and, in the course of protracted negotiations, offered a comprehensive response.[31] Houthi authorities rejected the offer and pressured the UN to deliver.[32] As aid workers argued at the time, the fact that the offer of a principled comprehensive response by an organization well placed and mandated to carry it out was being turned down should have led to pause for thought.[33] Attempts to access the location by the UN were not easy, and there were clear warning signs about authorities’ intention to use the assistance for their own military and political gain. With each attempted delivery, Houthi authorities tried to interfere in the supplies being sent to the city. For example, the Houthi-run National Authority for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (NAMCHA)[34] continually attempted to influence what type of aid would be carried (to the extent that it stated authorization would not be provided unless certain items such as medical supplies were on board). Pressure on agencies led to nonstandard items being authorized for procurement and distribution. Fresh fruits and vegetables, for example, were not routinely provided to civilians in need because they spoil quickly, but were included in the first shipment at the insistence of Houthi authorities. Authorities continued to pressure for an increase in commodities, especially food, despite no independent assessment of needs on the ground. Attempts were made by Houthi authorities within NAMCHA to send additional trucks to accompany UN-supplied trucks or to load additional items on the trucks. These attempts were rebuffed, with UN personnel at one point turning away crates claimed to be food and medicine that Houthi authorities had brought to the loading point. This is extremely sensitive as any commodities that are not UN-issued or -sanctioned can be seen by external parties as the UN providing support to a party in the conflict, which breaches the principle of neutrality.[35] Another debate at the time surrounded the balance of the imperative of humanity versus neutrality and the principle of “first do no harm”; it involved frank discussion about the potential gain from the compromise made. The number of civilians in the city was minimal. The number of fighters was high. There were extreme protection concerns surrounding the civilians who remained. Past experience has taught that providing assistance, particularly food assistance, in highly militarized contexts can lead to civilians being targeted to appropriate the assistance, putting them even more at risk.[36] In addition, providing assistance would deeply compromise not only the foundational principles of neutrality and independence, it also would directly breach specific agency commitments based on these principles, which are posted in WFP offices around the world, including in Yemen. They include (emphasis added):

WFP is well aware of the risks related to the distribution of food aid. As far back as 2001, it was recognised that “food aid is the form of humanitarian assistance that is most easily and frequently manipulated and misused by parties to conflict to support their own purposes of warfare.”[37] It was also well aware that the food aid provided to Durayhimi city would not be going to civilians but would benefit fighters. A senior WFP official at the time acknowledged that “of course I know that the so-called families inside are military.”[38] The choice was, therefore, knowingly made to provide food assistance to military combatants, even with the understanding that the benefit to the small civilian population would be minimal and potentially put them at risk. The heavy military presence, diversion of supplies and a civilian presence of fewer than 100 was confirmed later in the year when humanitarians were finally allowed into the city.[39] The example of Durayhimi city clearly shows how far the response has been willing to bend and discard principles for little gain. The only apparent concession made by the Houthis was to allow a team to enter the city in exchange for the second UN aid shipment. The entire process of delivering aid to the city was fraught with interference and clear attempts to instrumentalize aid for military gain. As was witnessed by people on the ground, assistance such as dignity kits for women containing personal care products[40] were discarded by “authorities” and combatants and burned instead of being distributed to the few females present.[41] Witness reports confirmed the diversion and appropriation of assistance considered to be useful — mainly food items — from civilians to military actors, and detailed the extreme protection concerns of civilians inside, including their inability to leave.[42] The food aid delivered was not insignificant. In May 2019, a one-month supply of food items and rapid response kits was delivered for 300 households.[43] This should have lasted the actual number of civilians on the ground more than a year. A few weeks after the initial delivery, reports from Houthi authorities claiming that the assistance was finished led to renewed pressure on the UN to deliver again. As a result, in October 2019, the UN delivered a three-month supply.[44] This assistance more than likely fed and sustained thousands of soldiers for months in 2019. Considering the limited benefit for the few civilians on the ground and the increased risk the assistance posed to them, combined with the obvious benefit the assistance had to one side of the parties to the conflict, the balance clearly had tipped in the wrong direction. At the end of the day, what consequences or benefits the assistance had will never be widely known: The mission report from October 2019, when some aid staff finally went in, was confidential; findings were never transparently shared within the humanitarian community. Participants on the mission also were instructed by senior agency management to not speak about events that occurred on the mission or what was found. The only clear instruction from senior humanitarian leadership after the October mission was that no further deliveries would be made to the location by the UN.[45] Durayhimi city events and the end results of the assistance provided remains shrouded in secrecy. |

What proponents of the stance that no price is too high to pay to fulfill the principle of humanity often overlook is that adhering to all of the other principles is the only way to effectively accomplish that final objective of alleviating suffering. If a response cannot establish and respond to needs in an independent, neutral and impartial manner, then acceptance, security and access are eventually compromised, which leads to the cessation of assistance in the longer term. Furthermore, the probability that a response that lacks independence is reaching those most in need rather than those who will benefit politically, militarily or financially is slim, so it will not address or alleviate suffering.

When the most strategic leadership imposes a framework in which humanity trumps all, it is hard for those on the ground to apply principles, especially in moments of substantial pressure. Inevitably, then, adherence to principles diminishes across the response. This was seen, as noted in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Sustainable Access and Redlines‘, during the 2018 battle of Hudaydah, when the senior humanitarian leadership in Yemen sidelined efforts to ensure the independence of needs assessments and beneficiary identification in favor of mounting a rapid response. This decision undermined later attempts to insist on independent beneficiary selection and registration, setting a precedent that was then hard to roll back both in Hudaydah as well as other Houthi-controlled areas.[46]

Politics, Money and the Thwarting of Independence and Neutrality

In an ideal scenario, humanitarian action would be completely neutral and devoid of political influence. Realistically, however, it always takes place within a certain political context; more frequently than not, it takes place in one that is highly complex. Even in best-case scenarios, humanitarian response necessitates interacting with the political actors and systems that exist within the operational environment. For example, at the most basic level, aid personnel require political authorities’ permission to undertake their work; this includes obtaining visas and securing access on the ground.[47] Humanitarian response often also takes place in the middle of situations with ongoing peacekeeping interventions or political mediation processes. This has been the case in South Sudan, the DRC, Afghanistan, Iraq and Yemen. In all of these scenarios, humanitarian aid has had to find a way to distinguish itself from these processes to maintain the neutrality and independence that ensure acceptance. At the same time, it must be recognized that these political processes affect response and, similarly, that humanitarian response can affect political efforts.

In addition, humanitarian response is inherently influenced by politics because it is funded by donors with political agendas, an issue discussed later in this report. Since the early 2000s, many discussions have been had around the acknowledgement that humanitarian aid is being integrated into donor strategies to advance donors’ own agendas.[48] More recently, a January 2021 panel discussion reflected on the use of humanitarian aid as part of the broader US agenda in Yemen rather than solely to alleviate humanitarian need and noted other countries also have used aid in various contexts to achieve their political goals.[49]

Neutrality and Politics: The Stockholm Agreement, Hudaydah and the Joint Declaration

Even though the lines between politics and humanitarian aid are not always clear, and interaction is inevitable, a principled response requires maintaining neutrality to the greatest extent possible. Yet in Yemen, the political and the humanitarian have become intertwined over time to an uncomfortable degree. This can be seen clearly through the Stockholm Agreement of 2018, the housing of political personnel in humanitarian quarters in Hudaydah and the current Joint Declaration being advanced by the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen (OSESGY) as a solution to the conflict in Yemen.

The Stockholm Agreement

By 2018, the war in Yemen had been dragging on for more than three years. Attempts to bring parties to the table to mediate an end to the crisis had not succeeded and, militarily, the conflict was intensifying. By mid-year, Saudi- and Emirati-backed forces had battled their way up Yemen’s Red Sea coastline and were readying for an offensive against Houthi forces entrenched in the port city of Hudaydah. Concerns about the humanitarian consequences of a battle for Hudaydah invigorated efforts to push the warring parties to find some common ground. Ultimately, they did to varying extents, and on December 13, 2018, an agreement was signed in Stockholm and endorsed by the UN Security Council. It called for a cease-fire and redeployment of forces for the ports of Hudaydah, Salif and Ras Isa, provided a memo of understanding to serve as the basis for further discussions on easing fighting in Taiz, and it set up a mechanism to prepare for prisoner exchanges.[50]

The Stockholm Agreement mixed military and political progress with humanitarian objectives. While parts of it, for example, dealt with the redeployment of forces, cease-fires, a halt to hostilities and a prisoner swap, other parts related to facilitating the movement of humanitarian aid and the opening up of humanitarian corridors.[51] Parties involved recognized the importance of addressing the humanitarian situation, and acknowledged it had motivated the Hudaydah cease-fire and redeployment.[52] What was also significant was that humanitarian organizations were deeply involved and backchanneling during the negotiating process.[53]

Initial hopes that the agreement would enable a comprehensive peace deal down the line never materialized as implementation stalled shortly after its signing. The Hudaydah cease-fire has been violated regularly, throughout 2019 to date. By January 2020, coalition forces had accused the Houthis of committing at least 13,000 violations since the start of the December 18, 2018, cease-fire.[54] The redeployment of forces from the ports and other key parts of Hudaydah city also has failed, despite many follow-up meetings on the matter. The prisoner exchange lagged with no significant exchanges until the latter half of 2020, and the Taiz component remains unimplemented.[55]

With little movement on the political and military front in regard to implementation of the agreement, pressure mounted on the humanitarian community to showcase progress on the humanitarian side. One result of this was the pressure for UN humanitarian agencies to respond to the situation in Durayhimi, as described above.[56] Having to rely on humanitarian indicators to save face on a political agreement led to the uncomfortable involvement of political entities such as the OSESGY and political departments of the UN in New York in humanitarian discussions, with frequent requests[57] for the response to accommodate political considerations when making decisions.[58]

The Stockholm Agreement, how it was negotiated and the subsequent lack of implementation, set a bad precedent. Looking to start afresh, 2020 saw a new initiative from the special envoy. At the end of March 2020, a Joint Declaration was proposed that included a proposal for a nationwide cease-fire, economic and humanitarian measures to build confidence and ease suffering, and a commitment to resume the political process,[59] which had remained stalled by the end of 2020.[60]

The special envoy cited disagreements over the humanitarian and economic relief components of the Joint Declaration as holding up the process.[61] The continuation of using a strategy that intertwined the humanitarian with the political, with the intent of using humanitarian issues as building blocks toward a peace agreement, was deeply flawed and continues to undermine the response’s independence and neutrality from the political process. Only when humanitarian actors, not political ones, negotiate humanitarian issues can it be ensured humanitarian suffering is not instrumentalized for political purposes. That humanitarian issues became partly responsible for holding up a peace agreement provides an ironic lesson to this effect.

Integration Struggles: Humanitarian Space in the Hudaydah Context

Politics and humanitarian aid collided on a very practical level in 2019. As noted in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Security‘, the security framework restricts UN staff to living spaces that have been cleared by the UN Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS), and it can take months to find, renovate to meet requirements and gain approval for new quarters. At the beginning of 2019, one office and two guest houses were available in Hudaydah to host all necessary UN agency staff from nine UN agencies, funds and programs. The Hudaydah hub also serves Hajjah governorate, so housing all necessary operational staff was a tight squeeze; some agencies had been allocated only one slot. Following the Stockholm Agreement, the UN created and deployed in Hudaydah the UN Mission to Support the Hodeidah Agreement (UNMHA) to oversee implementation. The civil observer mission consists of civic authority, military and police personnel.[62] Space needed to be found to house the mission, and in early 2019, the humanitarian response was requested to detach one guest house to UNMHA. The discussion quickly led to a standoff between the humanitarian leadership and the UN political side over priorities, but the response acquiesced. This reduced the number of humanitarian operational staff able to be present in their duty station and oversee activities and programs, and inhibited any additional staff from visiting the area to provide technical and surge support when necessary.[63] It also made the Yemen response look more like an integrated mission, one in which political and humanitarian components form part of a broader strategy to achieve a common goal.[64]

In March 2019, UNMHA requested additional accommodation space from humanitarian agencies in Hudaydah through the use of two rooms within the remaining humanitarian guest house. Pressure from the political leadership citing the priority of the political mission forced senior humanitarian leadership to consider the request, [65] which was poorly received on the ground. On a very practical level, the request would have resulted in one humanitarian agency having to leave Hudaydah due to a lack of space, directly affecting the delivery of humanitarian assistance in one of the worst-affected areas in Yemen. Of broader concern were the risks associated with mixing political and humanitarian UN staff. UNMHA staff are subjected to a higher level of scrutiny, surveillance and restrictions from local authorities by nature of their role in Yemen. Mixing personnel, humanitarian staff pointed out at the time, could have led to confusion surrounding the identity and mandate of humanitarian aid workers, increasing the risk of furthering the already extensive restrictions for humanitarian personnel and affecting humanitarian programming.[66] Following lobbying from humanitarian personnel, the request was denied, safeguarding the neutrality of humanitarian space and ensuring continued ability to deliver. The issue was eventually solved by the arrival of a ship, which houses the UNMHA mission to date.

Coordination between the humanitarian and political sides of the UN predates the Yemen response, so established guidelines and policies exist. Under these guidelines, activities and objectives of special missions, UN peacekeeping operations and UN humanitarian actors should be coordinated and strategically aligned. However, they also clearly state that special missions and peacekeeping operations cannot dictate or influence activities and operations of UN humanitarian actors, and that “integration arrangements should take full account of recognized humanitarian principles [and] allow for the protection of humanitarian space.”[67] In addition, studies on the impact of UN integration on humanitarian action have routinely highlighted the importance of not co-locating political/military and humanitarian staff in order to maintain distinction, particularly in highly politicized contexts.[68]

Advocacy and the Battle of Hudaydah

A last example of the complexity between politics and principles relates to advocacy done by humanitarian actors ahead of the battle for Hudaydah. In 2018, Emirati-backed local forces within the anti-Houthi coalition, with the support of Yemen’s internationally recognized government, regained control over territory on Yemen’s western coast. A final phase of the military push was the plan to recapture Hudaydah city and port from the armed Houthi movement.[69] The intention of the Emirati military planners to undertake this path was clear; the UAE requested humanitarian organizations leave Hudaydah city by June 12, 2018.[70]

Humanitarian organizations feared a battle to take back Hudaydah would lead to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of civilians, result in a high death toll, disrupt key imports into the city’s port and push Yemen into famine.[71] As a result, the humanitarian response together with organizations including International Crisis Group and Human Rights Watch launched an intense public and private advocacy campaign for the Saudi-led coalition and key actors, including the United States, to halt the offensive.[72]

Ultimately, the offensive stopped on the outskirts of Hudaydah city. Regardless of whether humanitarians’ advocacy affected the decision to halt, it did prompt debate about whether humanitarian agencies crossed a line in advocating heavily against a military strategy of a party to the conflict. Neutrality implies non-interference, though humanitarian advocacy is common and accepted in, for example, areas where parties to the conflict are being urged to abide by their obligations under international humanitarian law (IHL). Such advocacy includes seeking to safeguard hospitals, schools and civilian houses and infrastructure, and to ensure safe corridors for fleeing civilians. Six aid workers interviewed, however, specifically raised concern that advocating for or against a decision to implement a military strategy ultimately crosses the humanitarian community’s own neutrality principle and pushes the boundaries of humanitarian advocacy too far.[73]

Neutrality and Money: Where Does the Money Come From and Where Does it Go?

Saudi Arabia and the UAE

Another ethical dilemma that has divided opinions within the response surrounds the acceptance of funding from major parties to the conflict and how that impacts the principles of independence and neutrality. Seventeen key informants raised concerns about the willingness to accept Saudi Arabia and the UAE as donors to the humanitarian response, including for projects and activities that are implemented in areas under the control of the armed Houthi movement.[74] The two Gulf states have led the military coalition backing the internationally recognized Yemeni government in its fight against the armed Houthi movement. Saudi Arabia still leads the aerial campaign, which has been accused of disproportionately and indiscriminately targeting civilians, civilian infrastructure, health facilities and agricultural land.[75] Until 2019, the Emiratis maintained a significant physical presence on the ground, supporting and training troops and taking charge of the West Coast offensive in 2018. The UAE has since drawn down its forces, though it maintains a minimal presence as well as influence with the local forces it previously trained and funded and with those forces’ political allies.

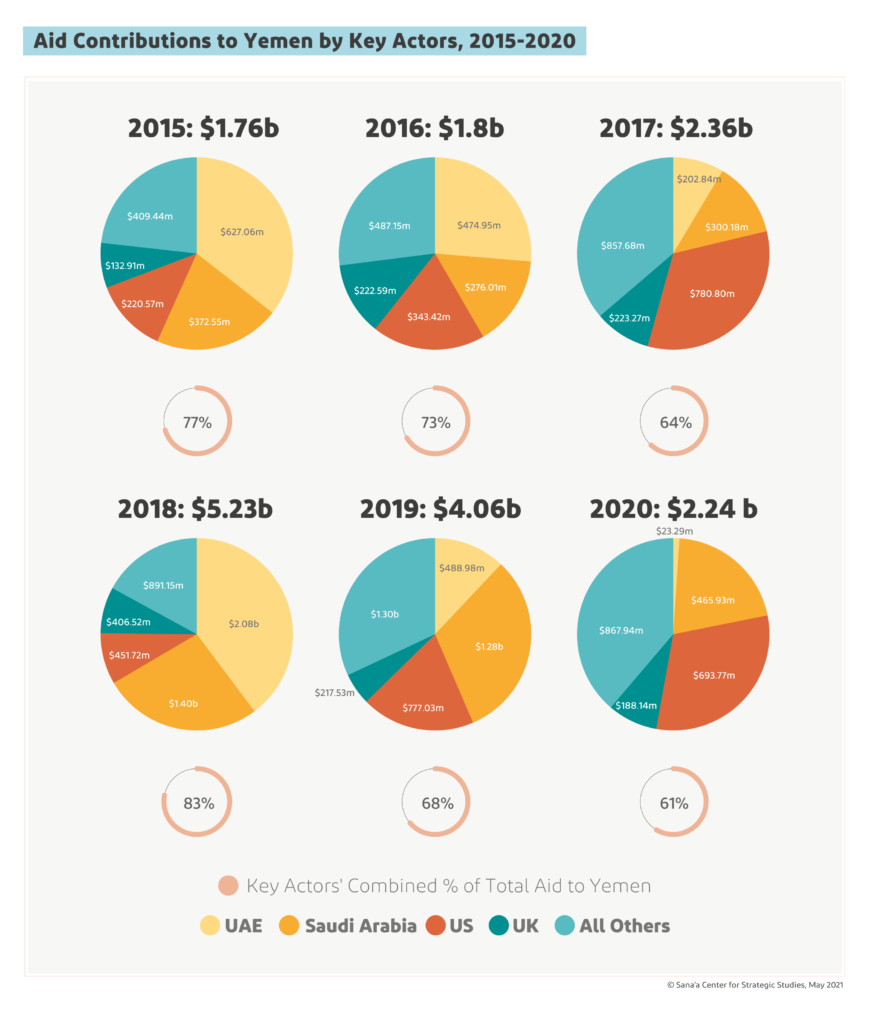

The Saudis and Emiratis are undeniably key parties to the conflict, and both have been big donors. Between 2015 and 2020, Saudi Arabia spent US$4.07 billion on the humanitarian response in Yemen.[76] Of that, US$1.73 billion went directly through the humanitarian response plan funding process, and more contributions were paid directly to other agencies.[77] In 2019, Saudi Arabia was the biggest donor to the humanitarian response, with its $1.28 billion representing 32 percent of total funding.[78] In 2018, the UAE was the biggest donor, providing 40 percent of total funding, followed by Saudi Arabia, which provided 27 percent.[79] Saudi Arabia also co-hosted the 2020 humanitarian pledging conference.[80]

The US and the UK, which have supported the Saudi-led coalition politically and with arms, logistics and military expertise, also have been key donors. Other European aid donors have lesser but still lucrative defense industry deals with coalition countries. During the 2019 standoff between the UN and the Houthis over aid diversion and interference, one donor country, already under domestic pressure over arms sales to Saudi Arabia, directly requested that WFP not suspend aid in northern Yemen. It cited concern that such a suspension would lead to more pictures of starving children, which would affect its constituency’s willingness to continue the arms sales.[81]

Figure 5.1

Source: UNOCHA Financial Tracking Service[82]

Source: UNOCHA Financial Tracking Service[82]

Those who defend accepting funds from parties to the conflict[83] generally cite international law, specifically that such parties are responsible for ensuring the provision of humanitarian assistance to populations in need.[84] Proponents of this view maintain that the role of warring parties in causing humanitarian need leads to a financial responsibility to alleviate this suffering.[85] While IHL does obligate parties to the conflict to allow humanitarian access,[86] it does not state that parties to a conflict have a financial responsibility with regard to providing humanitarian assistance.[87] In addition, purporting that Saudi Arabia and the UAE have a financial responsibility toward alleviating need paradoxically assumes guilt and assigns blame to a party in the conflict, directly undermining the neutrality principle.

The opposing viewpoint holds that there is an innate conflict of interest in accepting funding from countries that perpetuate the suffering of the civilian population while also sending humanitarian assistance.[88] Those on this side of the argument consider accepting money from parties to the conflict as directly undermining the neutrality of the response. Earmarked funding, whether for a specific activity, sector, geographical region, etc., is viewed as even more problematic as it not only undermines neutrality but also the independence of technical agencies and organizations to allocate funding based on need, not political considerations. Another general concern is that countries may use high levels of funding to somehow absolve themselves of their primary responsibilities to respect IHL and protect civilians.

The US and the UK are prominent donors to the response, and also provide significant amounts of arms to Riyadh and the UAE.[89] The US and UK also have provided direct assistance to the Gulf military coalition through their armed forces, including aerial targeting assistance, intelligence sharing and mid-flight aerial refueling.[90] The ethical dilemma, therefore, reaches beyond just those directly involved on the ground.

Figure 5.2 Sources: SIPRI, UNOCHA Financial Tracking Service

Sources: SIPRI, UNOCHA Financial Tracking Service

As a result, even during 2015 and 2016, many organizations active in areas under Houthi control declined to take funding originating from Saudi Arabia and the UAE.[91] This became especially important in instances when other organizations, which took a less principled stance, directly promoted their donors while undertaking field activities. For example, in 2017, one organization implemented an activity in Ibb, in an area under the control of the armed Houthi movement, while sporting a Saudi Arabian flag.[92] Such blatant disregard for neutrality subsequently undermined acceptance of the organization and its activity in the community and with the authorities, complicating its ability to maintain access and carry out activities. Such examples are not unique.

There is no clear guidance on parties to the conflict also being donors to the humanitarian response, and the sensitivities surrounding the issue are not unique to Yemen. Even if organizations accepting funding from donors such as Saudi Arabia or the United States act in a principled manner, that means little when acceptance is directly linked to the perceptions of those receiving aid. And having the major donors for the response, including the US and UK in addition to Saudi Arabia and the UAE all heavily involved in the conflict itself does not lend well for this perception.[93]

Direct Funding to Houthi Authorities

The implementation of humanitarian assistance in Yemen differs to that of other response contexts. Not only does it encompass the direct delivery of humanitarian services by (I)NGOs, but it also invests heavily in institutional support through ministries and government institutions.[94] This is particularly pervasive in the health and WASH sector but runs through most areas of the response, including food and livelihoods.[95] Direct use of parties to a conflict to implement humanitarian aid — and direct funding to these parties as a result — is not a practice that is used or accepted in other response contexts simply due to its direct breaches of neutrality, impartiality and independence. This is a red line elsewhere and a modality left to development agencies and programs.

When humanitarian actors took over from development programs in 2015, the escalation of the conflict that prompted the Level 3 emergency response was widely expected to be short-lived. At the time, ensuring minimum services provided by government agencies would continue was considered beneficial to a quicker return to stability; many of these services had already been receiving UN development support. As a result, support to institutions continued where it was possible to do so.[96]

Six years later, this model has not changed. Support continues to be funneled largely through government institutions. This can be seen for example in the WASH sector, in which it was reported in 2019 that authorities handled the implementation of 78 percent of the sector’s total response activities.[97] WHO also focuses almost exclusively on support to health institutions through the separately run health ministries operated by the Yemeni government in Aden and Houthi authorities in Sana’a rather than focusing on direct implementation.[98] The ability of this more development-oriented response to ensure continuation of services arguably still could make quick rehabilitation of services easier once the conflict ends. But, in areas under the control of the armed Houthi movement, this practice seems to have spiraled out of control.

In February 2020, The Associated Press reported that approximately US$370 million was paid directly to Houthi authorities and Houthi-controlled government institutions for salary payments and other administration costs; a third of this money was not audited.[99] This is in addition to money paid to line ministries as implementing partners, as discussed in ‘To Stay and Deliver: Sustainable Access and Redlines‘, and financial or management support to government-run programs such as the Social Welfare Fund.[100] Much of this support, which began in the early days of the response, was temporarily halted in late 2019 after senior leaders began to realize multiple agencies were paying salaries and operational costs to Houthi-run ministries and NAMCHA. This prompted them to demand all agencies report the extent of their money flowing to Houthi-based authorities.[101]

The problem was clear: a significant chunk of humanitarian assistance intended to go to beneficiaries and alleviate suffering was directly going to a party to the conflict. In addition, UN records could not account for at least one-third of this money,[102] meaning a credible possibility existed that humanitarian financing was directly being used for the war effort or other reasons beyond humanitarian assistance. In addition to undermining neutrality, this runs counter to the basic goal of alleviating suffering rather than prolonging it. What is less clear is how significant this problem remains today. Monitoring in general, of humanitarian financing as well as aid resources and programs, has been insufficient throughout the response, an issue addressed in ‘Accountability Falters When Oversight is Outsourced’. Despite attempts by senior humanitarian leadership in 2019 to halt this practice of directly providing financial support to warring parties, seven interviews with key informants confirmed that UN agencies were continuing to channel money for direct payment of salaries and administration to Houthi authorities. According to their information, two UN agencies pay the salary of the Houthi-appointed health minister and at least one UN agency continues to provide funding for operating costs to SCMCHA.[103]

Impact on Perceptions Among Yemeni Humanitarians and the Public

Humanitarian principles themselves are clear and provide a framework that guides humanitarian action. In reality though, once principles begin to interact with a contextual environment, their application becomes more complicated. Compromises that may need to be made to ensure effective aid delivery require analysis and consideration, and should be applied according to accepted frameworks such as that of last resort. It is important that every choice and compromise is weighed against the final value of delivery as well as the longer-term consequences.

In Yemen, many compromises have been made that have diminished operational space over the years to the extent that, out of 42 key informants interviewed, only four said that the response is sufficiently principled, and none of those four considered it a wholly principled response. In addition, three Yemeni aid workers interviewed by the Sana’a Center for this report directly stated that the response was unprincipled[104] and uncredible.[105] Other perceptions shared included a concern the response was allowing authorities to direct aid[106] and that the response was in Yemen to make money rather than to provide assistance.[107] More concerning is that none of the 30 Yemenis interviewed by the Sana’a Center expressed a positive view of the response. In addition to being perceived as unprincipled, those interviewed highlighted other negative perceptions of the response, ranging from corruption,[108] the lack of a timely response,[109] that the response misunderstands Yemen and its needs,[110] and that there are gaps in the response.[111]

That the Yemen response has an image problem is not a secret. It has been hit hard by constant accusations of corruption, diversion (by both authorities as well as the UN and aid organizations themselves), poor quality of aid (particularly food), and it is portrayed as insensitive toward the Yemeni population. One of the more well-known social media campaigns to hit Yemen in recent years has been the “where is the money campaign.” A group of Yemeni activists and financial experts started the campaign in April 2019, focusing on transparency and accountability of the financial resources flowing into Yemen. They claimed that despite the billions of dollars of aid being allocated for Yemen, the situation was not improving. For this reason, the activists requested the aid sector to be more transparent about expenditures and aid allocation.[112] The same request has been supported by national aid workers interviewed and surveyed during the course of the research for the report.[113] Out of those 30 interviews, 42 percent of the respondents had a negative perception of how organizations were spending money, saying it was more to the benefit of international organizations than the Yemeni population.

Two issues exacerbate the problem. The first is the ability of authorities, particularly the Houthi movement, to exploit the portrayal of a corrupt and badly managed humanitarian response to further undermine community acceptance and humanitarian ability to operate. Houthi officials have adopted strong anti-aid rhetoric, including accusing humanitarian organizations of colluding with foreign intelligence services and serving the interests of donors more than the Yemeni people. Twitter, Facebook, Telegram and other sites are full of negative reports about aid delivery in Yemen.[114] While the criticism has usually come from Houthi authorities, similar attacks have originated from supporters of the internationally backed government since January 2021, when the UN opposed a move by outgoing US President Donald Trump to designate the armed Houthi movement a foreign terrorist organization, triggering sanctions.[115] The origins of aid financing, as previously discussed, do not help the portrayal of the response as neutral from other objectives.

A second issue pertains to the (in)ability of the aid community to communicate effectively and transparently. Little has been done in past years to engage with communities about the response’s objectives, how humanitarians work and how and why certain segments of communities are targeted and others are not.[116]

In addition, the narrative that has been commonly portrayed by the international community as seen in ‘The Myth of Data in Yemen’, also sets the response up to fail. Prior to COVID-19 in 2020, the stated number of people in need articulated in every public communication and article on the Yemen response was 24 million. But humanitarian programming in Yemen did not target 24 million people; it targeted a certain caseload of that number, 15.6 million people.[117] But how caseloads are identified and selected is not well explained to the Yemeni population, who prior to 2015 had little experience with humanitarian aid. As a result, complaints about inclusion for services and gaps in coverage are myriad, and they are reflected in hotline complaints where, among the most frequent requests, are explanations of how to register and what the criteria are for inclusion.[118]

Illustrating this lack of understanding, international aid workers interviewed for this report overall agreed that funding to Yemen has been high, and that the ability to effectively respond has to do with the failure of aid workers and leadership to run a good response rather than funding levels. As highlighted in ‘Challenging the Narratives,’ Yemen remains the second-highest funded response globally. National aid workers, on the other hand, all perceived the response to be underfunded based on the needs. When looking deeper into their responses, what becomes clear is that they considered the response to be underfunded because it does not cover all of the needs. Among the responses were descriptions of the aid as “unsubstantial” and “ineffective”,[119] and “not at all appropriate to the needs of the population.”[120] One Yemeni aid worker said the response is only “somewhat adequate because it does not provide for all the population’s needs, and [operates] for temporary periods of time. Also, the quantities and rations being distributed are not sufficient compared to the number of members of households.”[121] Another, asked about access constraints, referred to funding levels, describing donors as the biggest obstacle to addressing the population’s needs.[122]

Humanitarian aid will never cover all needs, in any context. The role of humanitarian aid is to carry out life-saving activities. If even within the sector this understanding does not exist, then it is not surprising that it is misunderstood in local communities and by beneficiaries. Misinformation and misconceptions will continue to swirl and cause frustration, prolonging the negative cycle, as long as the scope of aid is not understood.

The Challenge Ahead: Reclaiming a More Principled Response

Many compromises have been made in the Yemen response. Examples such as Durayhimi and the loss of control over independent assessments and aid delivery indicate a significant loss of independence and neutrality. These compromises have been excused by senior humanitarian leadership both in Yemen and New York in the name of humanity. Yet, the compromises made have not led to a better and more inclusive delivery of aid, nor do they show any sign of abating. Compromise in Yemen has become the norm rather than the exception.

In addition, questions must be asked about whether these compromises have now shifted the response into an area where it does more harm than good. The significant diversion of humanitarian material and financial resources to at least one party of the conflict is likely enabling them to sustain a war that has been devastating the country since 2015. The response in Yemen must evaluate whether its ability to save lives has not been irrevocably compromised by the choices it has made.

Reclaiming a principled operation will require fundamental shifts in approach and a complete redesign of how humanitarian aid is implemented in Yemen. Humanitarians must take control of both establishing need and implementing aid independently. They must also look hard at how aid is being instrumentalized to further political and military goals, whether through diversion of resources (in terms of commodities such as food as well as finances in the form of institutional support) or through the manipulation of aid to feed a failing peace process. The road back to a more independent and neutral response will be painful. Strong resistance can be expected from authorities on both sides of the conflict who have benefitted from the constrained operating space it has created and lack of oversight and control, as well as from some organizations who benefit from the current status quo.

In addition, one of the biggest challenges will be to change the overall negative perception of the humanitarian response in Yemen. More work is required to ensure the system itself is clear and transparent about what it can and cannot do and how it works, with purposeful efforts made to counter wrong information. New and innovative strategies need to be put in place to deal with the negative propaganda machine. It is also important to recognize, as discussed earlier, the crucial roles of accountability and transparency: Ultimately, the best way to improve perception is to run a good response, with interventions and assistance that positively impact communities and are delivered in a timely and principled manner. This is necessary within the communities where humanitarians work, which perceive the response as biased, unfair and serving the personal interests of parties to the conflict and individuals within the humanitarian sector. It is also important for aid workers, whose will and motivation to even try to make changes are fading in the face of an increasingly narrow operational space and an unprincipled operational mode.

Recommendations

The Yemen response has been and continues to be held hostage by parties to the conflict and openly used to further political goals and foreign policy objectives. The response must find a way to restore its independence, neutrality and impartiality. The current way of operating is untenable, constraining the operational environment in a manner in which aid delivery is deeply compromised and potentially does more harm than good. At a minimum, the response needs to ensure that aid is delivered on the basis of independent assessments of needs and is not instrumentalized for political and military gain. Humanitarian agencies need at least a broad idea of where assistance is going and a certainty that it is not being used by the parties to perpetuate the war. A clear divide must be set between humanitarian and political negotiations, and humanitarian aid should not be used in attempts to influence political settlements among parties to the conflict or as a tool for broader foreign policy objectives that disregard the people on the ground. Of key importance is the need to change the perception of the Yemeni population that the response and aid workers are present only for their own gain and to further other objectives than providing humanitarian assistance. Their security and operational capability depend on it. To this end, specific recommendations are as follows:

To Senior Leaders of the Yemen Humanitarian Response

- Recognize that while addressing needs and upholding the principle of humanity is the end goal of any response, this cannot be achieved by ignoring the need to respect the other principles of independence, neutrality and impartiality. Toward this end:

- Stop using parties to the conflict, including their civilian entities, to carry out humanitarian assistance given their personal, military and political interests in where aid ends up;

- stop funding and providing material support either directly or through humanitarian assistance to parties of the conflict;

- develop and support a baseline for the humanitarian response that clearly sets out operating principles, thresholds, redlines and consequences for violations. Ensure that these operating principles are adhered to by the whole humanitarian community by putting in place reporting requirements and a compliance mechanism as well as the requirement for consensus on any compromises made; and

- only authorize compromises under the principle of last resort with a particular focus on ensuring they are for lifesaving purposes only and are limited in time and scope. Compromises should be carefully considered and evaluated before being authorized for use.

- Undertake a full analysis of the response to evaluate:

- Whether the current modality of response is achieving its goals; and

- the role of the Yemen aid response in a war economy so as to ensure that humanitarian resources do not contribute to war efforts by any party to the conflict.

- Protect the humanitarian response from being instrumentalized and used for political processes such as the Stockholm Agreement and the Joint Declaration pursued by the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary General for Yemen.

- Ensure internal complaints about actions and decisions that compromise principles are heard and addressed appropriately and transparently by independent bodies such as ombudsmen to ensure impartiality within the complaint mechanism.

- Communicate about the Yemen response in a more nuanced, transparent and accurate manner. To avoid creating false expectations, cease using sweeping generalizations, tropes and exaggeration in framing the narrative, and instead seek to create greater awareness of the role, objectives, capabilities and limitations of the Yemen response.

To Humanitarian Sector Actors within the Response

- Define and establish common positions on what constitutes principled response in order to foster collective and effective action. Adherence to the common position should be collectively monitored by the humanitarian community. Any breaches should be openly communicated to senior leadership and donors through a transparent and clear reporting system. If no remedy is found at the country level, aid workers should seek recourse through the ombudsman system.

- Improve the decision-making process when faced with operational difficulties that challenge principled action. To achieve this:

- Develop frameworks and guidance around ethical decision-making, which will contribute to better decisions by ensuring consideration of the ethical issues at stake in each situation;

- provide consistent training for national and international staff to strengthen their abilities to interpret and prioritize the principles, thereby building capacity in the area of principled decision-making; and

- ensure continuous external communication to all stakeholders on the principles of humanitarian aid, clearly indicating redlines and unacceptable conditions, and following through with consequences such as:

- temporarily suspending support (either geographically or to specific authorities), and conditionality for resumption;

- public statements on breaches of red lines and nonadherence to operating principles, ensuring the UN Security Council and donors are made aware of the constraints,

- Direct engagement by the most senior humanitarian leadership with relevant communities/authorities.

- Ensure assistance is not directly benefiting parties to the conflict instead of civilians. To this end:

- Cease using parties to the conflict to establish needs and implement humanitarian activities. Needs must be established independently and humanitarian aid should only be delivered by humanitarian actors unless authorized under the premise of last resort;

- have aid workers on the ground, including international staff, to undertake post-distribution monitoring instead of relying on local third party monitors; and

- put in place proper compliance mechanisms where reports of aid misuse are followed up on and addressed in a comprehensive and timely manner.

- If any doubts exist about who is benefiting, speak up and challenge the status quo.

- Put in place measures to transparently, honestly and constantly communicate with authorities, communities and beneficiaries on the modalities of aid, inclusion criteria and challenges faced to ensure understanding and mitigate frustration and negative perceptions.

To Donors

- Respect the neutrality of humanitarian response, and don’t use it to further political or foreign policy goals. To foster a clear divide between humanitarian and political initiatives:

- End the practice of earmarking or providing conditional funding based on the donor government’s interests and foreign policy goals;

- allow independent and impartial aid organizations to decide on needs and the resources required to address them; and

- support the humanitarian community when it pushes back against instrumentalization from the political sphere.

- Demand transparency and proper accounting from the UN and humanitarian organizations. For example:

- Stop allowing the use of humanitarian funding for activities that directly support institutions and parties to the conflict, including for paying salaries of SCMCHA officials and others in authoritative political positions.

- Develop indicators, guidance and compliance mechanisms to ensure funded organizations adhere to humanitarian principles, with clear clauses that penalize unprincipled actions.

- Engage with global humanitarian leadership to instruct and support their staff in Yemen in taking principled and ethical stands.

Up Next in this series of reports examining fundamental issues of concern in the Yemen humanitarian response is ‘Rethinking the System: Is Humanitarian Aid What Yemen Needs Most?’, which looks at a potential new avenue for the Yemen response through the implementation of the triple nexus concept, which has come to the fore in recent years. This report will look at the pros and cons of the approach and whether it is enough to change the current trajectory of the aid response and offer change to Yemen and its population.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security-related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

This report is part of the Sana’a Center project Monitoring Humanitarian Aid and its Micro and Macroeconomic Effects in Yemen, funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. The project explores the processes and modalities used to deliver aid in Yemen, identifies mechanisms to improve their efficiency and impact, and advocates for increased transparency and efficiency in aid delivery.

The views and information contained in this report are not representative of the Government of Switzerland, which holds no responsibility for the information included in this report. The views participants expressed in this report are their own and are not intended to represent the views of the Sana’a Center.

- “Joint Operating Principles of the Humanitarian Country Team in Yemen,” UNOCHA, October 23, 2016, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/joint_operating_principles_of_the_humanitarian_country_team_in_yemen_final_eng_2.pdf

- All 34 key informants asked about the application of humanitarian principles in the Yemen response expressed concern they fell short of an acceptable standard, including: INGO staff member #1, November 5, 2020; INGO staff members #4, #5 and #6, November 16, 2020; UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; donor 2, December 8, 2020, and donor 3, December 14, 2020; and a journalist, January 14, 2021.

- Angelo Gnaedinger, “Humanitarian principles – the importance of their preservation during humanitarian crises,” full text of remarks by ICRC director-general at the conference titled Humanitarian Aid in the Spotlight: Upcoming Challenges for European Actors, Lisbon, October 12, 2007, https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/statement/humanitarian-principles-statement-121007.htm

- Ibid.; author’s discussion with an aid worker for the Iraq response from 2015–2018, June 6, 2021.

- Interviews with senior UN expert, November 5, 2020; UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020; economic analyst #1, December 2, 2020; economic analyst #2, December 4, 2020; and UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020.

- These are humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence, voluntary service, unity and universality, proclaimed in Vienna in 1965. For further information, see: “The Fundamental Principles of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement,” ICRC, Geneva, August 2015, https://www.icrc.org/sites/default/files/topic/file_plus_list/4046-the_fundamental_principles_of_the_international_red_cross_and_red_crescent_movement.pdf

- “Resolution 46/182, Strengthening of the coordination of humanitarian emergency assistance of the United Nations,” UN General Assembly 46th Session, New York, December 19, 1991, https://undocs.org/A/RES/46/182

- “Resolution 58/114, Strengthening of the coordination of humanitarian emergency assistance of the United Nations,” UN General Assembly 58th Session, New York, December 17, 2004, https://undocs.org/A/RES/58/114

- “Challenges to Principled Humanitarian Action: Perspectives from Four Countries,” Norwegian Refugee Council and Handicap International, Geneva, 2016, pp. 8-9, https://www.nrc.no/globalassets/pdf/reports/nrc-hi-report_web.pdf; For more information, also see: Jeremie Labbe, “On the Road to Istanbul. How can the World Humanitarian Summit make humanitarian response more effective?” Chapter 2, “How do humanitarian principles support humanitarian effectiveness,” CHS Alliance, Geneva and London, 2015, pp. 18-27, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/chsalliance-humanitarian-accountability-report-2015-chapter-2.pdf

- “OCHA on message: Humanitarian Principles,” UNOCHA, New York, June 2012, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/oom-humanitarianprinciples-eng-june12.pdf

- Jean Martial Bonis Charancle and Elena Lucchi, “Incorporating the Principle of ‘Do No Harm’: How to take action without causing harm. Reflections on a review of Humanity & Inclusion’s practices,” Humanity and Inclusion and F3E, Lyon, France and Brussels, Belgium, October 1, 2018, pp. 4-12, https://www.alnap.org/help-library/incorporating-the-principle-of-%E2%80%9Cdo-no-harm%E2%80%9D-how-to-take-action-without-causing-harm

- A senior humanitarian leader directly stated this during a Humanitarian Country Team meeting in Sana’a at the end of 2018; remarks were confirmed in a November 2020 interview with an INGO staff member present in the meeting.

- The ‘last resort’ principle can be found in various documents, including: “Guidelines on the Use of Military and Defence Assets to Support United Nations Humanitarian Activities in Complex Emergencies. Revision 1,” Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), New York, January 2006, paragraphs 7, 26(ii), 30, 33 and 38, https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/01.%20MCDA%20Guidelines%20March%2003%20Rev1%20Jan06_0.pdf; “IASC Non-Binding Guidelines on the Use of Armed Escorts for Humanitarian Convoys,” IASC, New York, February 27, 2013, pp. 3, 6-7, https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/Armed%20Escort%20Guidelines%20-%20Final.pdf; and “What is Last Resort?” UNOCHA, New York, April 2012, https://www.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/Last%20Resort%20Pamphlet%20-%20FINAL%20April%202012.pdf

- These included US-based Global Response Management and NYC Medics as well as Berlin-based CADUS.

- The use of private security in humanitarian operations is controversial and no common policy exists to provide guidance on this topic. For further reference, see: Abby Stoddard, Adele Harmer and Victoria DiDomenico, “Private Security Contracting in Humanitarian Operations,” Humanitarian Policy Group, London, January 2009, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/96599/hpgbrief_33.pdf

- According to a case study, 19,784 patients were treated and an estimated 1,500 to 1,800 lives (including 600 to 1,330 civilians), although considering the complex and evolving situation at the time, definite figures are not possible. See: Paul B. Spiegel, Kent Garber, Adam Kushner and Paul Wise, “The Mosul Trauma Response, A Case Study,” Johns Hopkins Center for Humanitarian Health, Maryland, February 2018, pp. 36-39, http://hopkinshumanitarianhealth.org/assets/documents/Mosul_Report_FINAL_Feb_14_2018.pdf

- As authorized under the IASC “last resort” concept: “Operational Guidance on the Concept of ´Provider of Last Resort´,” IASC, New York, June 20, 2008, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/operational-guidance-concept-provider-last-resort; “Military and Defense Assets,” paragraphs 7, 26(ii), 30, 33 and 38.

- Spiegel et al., “The Mosul Trauma Response,” p. 4.

- “Military and Defence Assets,” paragraph 26, pp. 8-9.

- “For Us but Not Ours. Exclusion from Humanitarian Aid in Yemen,” Danish Refugee Council and the Protection Cluster, November 2020.

- According to the Global Humanitarian Overview for Yemen, since August 2020, some 19.1 million people in need were located in hard-to-reach areas, compared to 5.1 million people in April 2019. See: “Global Humanitarian Overview 2021, Part 2: Inter-agency coordinated appeals, Yemen,” UNOCHA, New York, December 2020, https://gho.unocha.org/yemen and “Yemen: Hard to Reach Districts (as of 29 April 2019),” UNOCHA, Sana’a, June 3, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/map/yemen/yemen-hard-reach-districts-29-april-2019

- Ahmed Abdulkareem, “The Forgotten War. Saudi Siege of Yemen´s al-Durayhimi as Devastating as WWII Siege of Leningrad,” MintPress News, Minneapolis, April 2, 2019, https://www.mintpressnews.com/saudi-siege-of-yemen-al-durayhimi-as-devastating-as-wwii-siege-of-leningrad/256820/

- “Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014,” Report of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts as reported to the UN Human Rights Council, September 3, 2019, pp. 123-124, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/GEE-Yemen/A_HRC_42_CRP_1.PDF

- Food to support approximately 300 households for 1 month, 300 emergency kits containing food, basic hygiene goods and the dignity kits that include personal care items for women and girls, as well as fruit, vegetables and water.

- Interviews with UN senior staff member #3, November 30, 2020, and UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020: A local partner drove the supplies truck into Houthi territory on the outskirts of Durayhimi city; it was offloaded there by a group of men who drove with it toward the city.

- “WFP brings vital humanitarian supplies to civilians trapped on the Yemeni frontline,” WFP, Rome, October 22, 2019, https://www.wfp.org/news/wfp-brings-vital-humanitarian-supplies-civilians-trapped-yemeni-frontline

- [27] Population figure is a 2017 projection by Yemen’s Central Statistical Organization based on the 2004 census. See: “Local Governance in Yemen: Resource Hub, Al-Hodeidah,” Berghof Foundation and Political Development Forum Yemen, https://yemenlg.org/governorates/al-hodeidah/

- Interviews with senior UN staff member #3, November 30, 2020, and UN staff member #4, December 9, 2020; the same numbers were shared with the author in September 2019.

- Interview with senior UN staff member #3, November 30, 2020; UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; and UN staff member #4, December 9, 2020; also shared with the author by community members and coalition forces in Durayhimi district in 2019.

- In Yemen at the time, only a handful of people had experience in handling similar situations.

- The offer included access to medical care and protection services such as the possibility to evacuate vulnerable cases.

- Interviews with senior UN staff member #3, November 30, 2020, and UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020.

- Ibid.

- NAMCHA preceded the Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (SCMCHA), which was formed by Houthi authorities in November 2019.

- Interview with senior UN staff member #3, November 30, 2020, and UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020; backed up by author’s experience during the process and detailed in an internal WFP analysis and recommendations paper on the risks and best way forward regarding deliveries to Durayhimi city.

- For further information on the risk of harm through provision of assistance in militarized areas, see: “The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response,” The Sphere Association, Geneva, 2018, p. 31, https://spherestandards.org/wp-content/uploads/Sphere-Handbook-2018-EN.pdf; “Protection in Practice: Food Assistance with Safety and Dignity,” WFP, Rome, 2013, Introduction and Part 1: Complex Emergencies, pp. 7-90, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/wfp254460.pdf; Jose Ciro Martinez and Brent Eng, “The unintended consequences of emergency food aid: neutrality, sovereignty and politics in the Syrian civil war, 2012-15,” International Affairs 92:1, London, 2016, pp. 153-173, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/ia/INTA92_1_08_MartinezEng.pdf

- Mary Anderson, keynote remarks at the Food Aid in Conflict workshop, Rome, 2001, WFP, as quoted in “Protection in Practice,” p. 15.

- Personal WhatsApp conversation between the author and the official in May 2019.

- “Protection observations. Mission to Ad Durayhimi 13-18 October 2019,” a confidential paper shared with the author in 2020.

- These kits contain underwear, abayas, hygiene products such as soap and washing powder and hygienic items for women and girls.

- Interviews with senior UN staff member #3, November 30, 2020, and UN agency staff member #4, December 7, 2020.

- “Protection observations.”

- One household is estimated at six people, therefore a one-month supply for 300 households is enough to feed 1,800 persons for one month. The civilians inside, confirmed by humanitarians to be 100 at most, should have had enough food to last 18 months.

- “WFP brings vital humanitarian supplies,” WFP.

- Emails shared with and seen by the author in a personal capacity during 2019.

- Interview with INGO staff member #4, November 16, 2020.

- Daniel Warner, “The politics of the political/humanitarian divide,” International Review of the Red Cross, Geneva, March 1999, Vol. 81, No. 833, March 1999, p. 112, https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/S1560775500092397a.pdf

- Devon Curtis, “Politics and Humanitarian Aid: Debates, Dilemmas and Dissension,” Overseas Development Group (ODI), Humanitarian Policy Group, London, April 2001, pp. 3-4, https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/295.pdf

- Jomana Qaddour, remarks during the panel discussion, “Humanitarian Aid and the Biden Administration: Lessons from Yemen and Syria,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Washington, January 15, 2021, from 34:30, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ETA-0zHm_-4

- “Full text of the Stockholm Agreement,” OSESGY, December 13, 2018, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/full-text-stockholm-agreement; see also, “A year after the Stockholm Agreement, Where are we now?” OSESGY, Amman, 2019, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/year-after-stockholm-agreement-where-are-we-now

- Ibid.

- Haydee Dijkstal, “Yemen and the Stockholm Agreement: Background, Context and the Significance of the Agreement,” American Society of International Law, Insights, Vol. 23 Issue 5, Washington, May 31, 2019, https://www.asil.org/insights/volume/23/issue/5/yemen-and-stockholm-agreement-background-context-and-significance