After eight years of absence from Yemen and my hometown of Sana’a, I decided to travel home, longing to see my family and loved ones after a long separation enforced by the war.

The flight from Amman took three-and-a-half hours, landing in Aden in the early hours of the morning. My older brother came to pick me up and accompany me on the 16-hour car journey home. We headed straight to Sana’a, stopping just once, at 3 am, to buy the popular Adeni delicacies of Khobz al-Tawa and Chai Adeni (thick flatbread and sweetened milk tea). Our driver, who knew the roads well, advised us not to waste time in Aden so as to avoid problems at checkpoints. In his experience, nighttime was the best time to travel, a time when soldiers didn’t ask too many questions, giving us a better chance of avoiding being detained for hours.

The hired car was from one of the companies now widely used to travel the country. Yemenis use these outfits to facilitate their journeys, since they deal with the multitude of checkpoints extending from Aden to Sana’a, and on to other cities in Yemen. It’s an expensive way to travel – as expensive as a flight – but it provides travelers with a modicum of safety on the roads.

A Perilous Ride Back Home

Everyone talks about the difficulties of traveling in Yemen since the start of the war, but no one can prepare you for the reality. The war has wreaked havoc. These were not the roads I once knew. I could not believe the cities looked the way they did. Almost a decade of war has made them unfamiliar.

As we made our way north, my brother joked that I should appreciate the roads that were still somewhat paved. I did not understand what he meant until we passed Lahj, taking a different route than the one we had used before the war. Yemen’s main highways have been closed off by the warring parties due to their proximity to the frontlines, to block access to opposing forces, or because of damage incurred in the conflict. Motorists now take alternative roads that are often unpaved, remote, and unsuitable for high volumes of traffic or heavy vehicles. These remote secondary roads often have limited mobile and internet coverage, roadside amenities, or emergency rescue services.

No matter how difficult or dangerous, Yemenis have had to find alternative routes to their destinations. Ours was through Wadi Hayfan. The path goes through a valley that acts as natural drainage for rainwater. The middle of the track is made up of rocks and boulders, with thick vegetation on both sides.

As we went through, I started to feel nervous. Could our car make it through this? It was still dark. Trucks filled with goods were in front of us, or going in the other direction, blinding us with their headlights. The narrow pass meant every couple of minutes we had to stop and make way for other vehicles. It took a couple of hours, moving at an excruciating pace, to make it through the valley. The driver told us that we were lucky to have made it through relatively quickly, noting that there are sometimes flash floods in the wadi, and people have to avoid the middle of the road so as not to be swept away.

Once we crossed the valley, a refreshing breeze picked up as the rays of the morning sun started to filter through. The view reminded me of the times my family and I would travel for holidays. We took these trips during the rainy season, when waterfalls and greenery covered these areas. I had memories of its beauty, but I was struggling to find any now. The roads were in utter disrepair, everyone you saw had a look of despair on their faces, and the trees were littered with different colored plastic bags.

We continued driving north, navigating the various checkpoints, which made the difficult journey even harder. After the twentieth, I stopped counting. Were it not for the desperate need to work or travel, no one in their right mind would put up with these conditions.

Approaching Sana’a

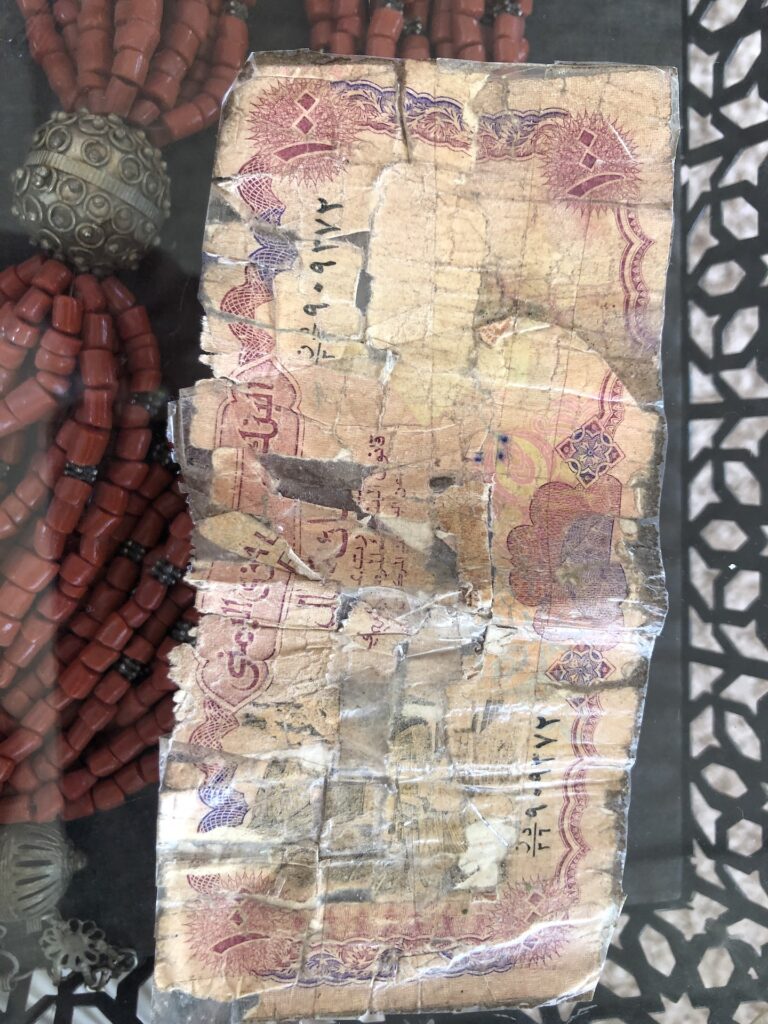

After hours of travel, we approached our first checkpoint under Houthi control. I saw a group of children and young men waving new rial banknotes, which are used in the areas under government control, and offering to exchange them for the old banknotes used in Houthi territory. I could not comprehend how these old banknotes, worn and wrinkled beyond recognition, held together more with tape than paper, were still being used.

Our car was stopped and we were asked to provide our passports, explain how we were related, and why we were traveling. Restrictions imposed by Houthi authorities mandate that women cannot travel alone and must be accompanied by a male guardian. Even if they present all the necessary documentation, unaccompanied women risk being detained at checkpoints until a male guardian picks them up. If the woman is an activist, an NGO employee, or affiliated with a political party opposed to the Houthis, they can be detained for days, and forced to pay a bribe or sign documents pledging adherence to the new rules.

Thousands of pictures of Houthi ‘martyrs’ displayed along the roads coupled with slogans of death and jihad, left no doubt that we had entered Houthi territory. It was a chilling experience that is difficult to put into words. It reminded me of a scene from the movie The Hunger Games, where the pictures of people who had died in a dystopian survival contest were displayed in a similar fashion. But this was reality, and these were pictures of Yemenis, many of them young, who had died on the frontlines.

As we approached the outskirts of Sana’a, I realized I no longer knew the areas we were passing through. New buildings and luxurious homes had sprouted without any visible planning or organization. There were dirt roads everywhere. It was difficult to even tell the paved roads apart, or know where they started and ended. The new houses stood in stark contrast to the destitute people walking on the streets, or the vendors on the sidewalk selling vegetables, fruit, and cheap clothes. They looked resigned, poverty and misery engraved on their faces.

A Bitter-Sweet Return

The first moments after my arrival at my family home in Sana’a are hard to describe. Reuniting with my family, and the moments of happiness that we shared, surrounded by the scent of home-cooked food wafting through the house, is what I replay in my mind. We ate on the floor so that the whole family could sit together, enveloped by the atmosphere of laughter and contentment. We stayed up late into the night. The next day was filled with visits to friends and relatives whom I hadn’t seen in eight years. I listened to stories of their daily lives, how it’s been since the war began, and the deteriorating conditions they face.

Yemenis now live without basic services like electricity, fuel, or cooking gas. Many have started to rely on solar power, while private companies have stepped in to provide electricity, albeit at a very high cost that few can afford. Incredibly, refrigerators have become a luxury item, used only by the few who have the means to keep them switched on. Groceries are thus purchased on a daily basis, and women only cook what will be consumed on the day, since it is no longer possible to keep leftovers. State services and salaries have become absent, with the de-facto Houthi authorities only stepping in to collect fines, Zakat, and the controversial Khums tax, which requires Muslims to pay 20 percent of their profits towards Ahl Al Bayt (descendants of the prophet).

Education in Yemen has also undergone a grave downturn. Public schools, which were once free, are now charging fees, the justification being that these are needed to pay teachers’ salaries. Due to difficult living conditions and public sector employees having not received regular salaries since 2016, many parents have had to either select which of their children can continue their education, or pull them out of school to look for work. In 2021, UNICEF quoted the number of children taken out of school at more than 2 million, many of whom have started working or been recruited to fight on the frontlines.

Schools also now adhere to the Hijri calendar, the Gregorian calendar no longer being used in territories under Houthi control. The de-facto Houthi authorities want Ramadan to mark the beginning of what was the summer vacation, even if Ramadan coincides with winter.

I talked at length about these changes with friends of mine. One, an academic at the College of Literature at the University of Sana’a, suggested I visit the university. As a former student and having taught there in the past, I took her up on the suggestion. The university felt eerily empty, with just a few students. As a public institution, students were not required to pay tuition in the past, but this too has changed, leading to a drop in enrollment. For women studying or working at Sana’a University, things are even harder. Bathroom facilities for female staff are now closed. I kept thinking to myself why such oppressive measures?

Women’s rights have been particularly hit hard. A week after I arrived in Sana’a, a social media campaign took off, led by several women activists and academics, who posted pictures of themselves wearing traditional Yemeni clothing under the hashtag #YemeniIdentity. Yemeni women’s traditional clothes are colorful, patterned, and detailed with intricate embroidery, with every region of the country displaying different styles. The campaign was a reaction to a decision by the Houthi authorities to close shops selling clothing that was not in line with their regulations. Shop owners were instructed to stop selling abayas that are short, form-fitting, colorful, or have frills. Abayas must now be black and lacking any adornment. This is just one measure among many that are limiting women’s participation in public life.

I spent a month in Sana’a, listening to countless stories of hardship from people I met, taking in the changes since the war, while being enveloped by the love of my family. But now it was time for me to go back.

A Stop in Aden

We arrived back in Aden on a Friday evening. We purposely chose Friday, a day off in Yemen, in the hope there would be fewer trucks going through Wadi Hayfan. As soon as I saw the sea, I forgot all about the strain and toll of the trip. Early the next morning, my brother and I went for a walk on the beach overlooking the Abyan coast, which has numerous hotels whose guests are mostly northerners traveling to Aden to reach its airport. Winter months, when the weather is mild, are one of the most beautiful times of the year to visit Aden.

Since the war, Aden’s cost of living has gone up and inflation is high. But compared to territories under the control of the Houthi authorities, civil servants receive more frequent salaries and electricity is still available, even if there are significant outages (especially problematic during the hot summer months). Government facilities and hotels use electricity generators, although not all residents are able to afford these.

A friend picked us up by car to take us for lunch in an area called Sirah, known for its fish markets. There, you can pick a fish of your choice and take it to one of the many restaurants to be cooked. We chose a restaurant with a table overlooking the coastline. It was full of families. The last time I had spent time in Aden was in 2009. My family and I used to travel to Aden during Eid vacation to enjoy its beautiful coastline and stay in one of the many hotels that had been built in the beginning of the 1990s. Aden was then a destination for Yemenis coming from all governorates. I couldn’t help but notice the way women were dressed. Nearly all were wearing face coverings (burqa) and dressed in black, which stood out in a city like Aden which can get extremely hot. In its heyday, Aden was a beacon of pioneering women in all fields of work. On that day, I did not see a single woman driving.

I also sensed reservation, if not outright discomfort, towards visitors from the north. Aden has witnessed vast destruction since the Houthis’ attempt to take the city in March 2015. The effects of war are heavily marked on the city’s buildings and homes. Many of its hotels have been destroyed. I discerned a sense of blame toward people from northern areas, colloquially sometimes referred to as Dahabishah, a derogatory term used since unification for people from the north. I could palpably feel the reluctance in the faces of the people I met, once I talked with them and they realized I was not from the city. I cannot blame Adenis for this.

A Changed Yemen and Threads of Hope

We had a dream when we gathered in Yemen’s squares back in 2011 demanding our right to a dignified life. But we have now become estranged in our own country – not just those of us living outside of it, but also those who have stayed. Traveling to Yemen from abroad has become easier than traveling from one governorate to another. Yemeni society has become fragmented, and the war, now in its ninth year, has changed all that we knew about our country. Living conditions are dire. The people look gaunt, and many seem to have given up on their dreams and aspirations for the future. The vast majority seem focused on just surviving the day. But there are signs of life, no matter how small. Defying all odds, I noticed how young Yemenis are showing incredible determination in trying to make ends meet, often innovatively. I was struck by the young women in particular, some of whom have set up small businesses to make a living, whether online or by opening home-based businesses. Despite these glimmers of hope, the overarching sentiment I was left with was that the country and its people can no longer bear the toll of this conflict. I cannot think of a single reason why this war should continue, but I can think of a million reasons why we need peace.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية