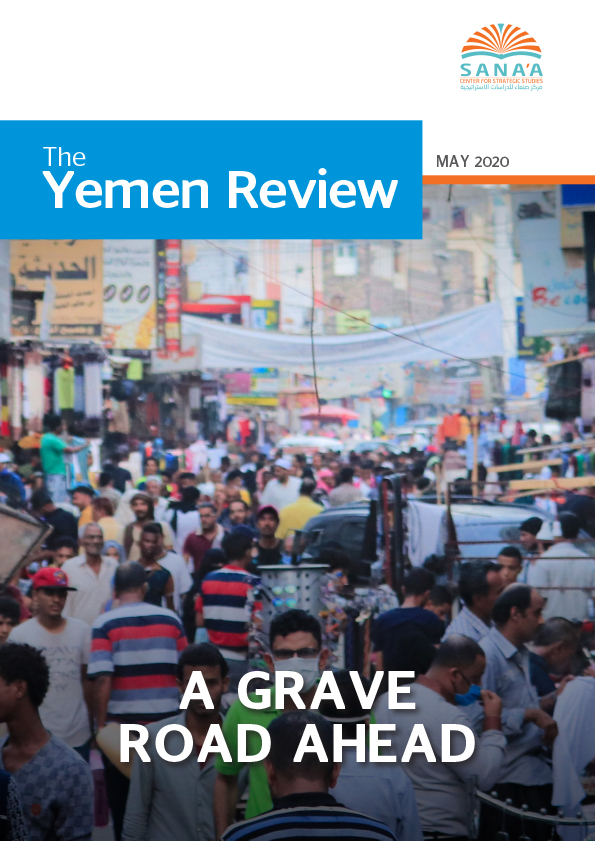

Shoppers crowd Al-Taweel market in Crater, Aden, on the last day of Ramadan, May 23, 2020, to prepare for Eid al-Fitr. Few people were seen wearing masks to protect against the spread of COVID-19 despite case numbers rising in May. // Sana’a Center photo by Ahmed Al-Shutiri

The Sana’a Center Editorial

Will Yemen Survive COVID-19?

There is a confluence of humanitarian and economic woes bearing down on Yemen that evoke the image of tidal waves cresting upon tidal waves, and average Yemenis have been left terrifyingly exposed. The United Nations estimates that 16 million Yemenis may ultimately be infected with the COVID-19 virus. Simultaneously, the warring parties’ response, or lack thereof, to the pandemic’s arrival has been stunningly reckless, and the ongoing retraction of international financial support for the country’s relief effort could not be more ill-timed. Available foreign currency in Yemen is also projected to enter a steep decline due to lost remittances and Saudi support for import financing ending, which will beget price shocks and increased unemployment. Seen through the sum of all these factors, the months ahead have come to appear sufficiently dire as to warrant consideration of whether it is still possible for Yemenis to save their country, or whether Yemen, as a political entity, will be unrecoverable after the pandemic passes.

Behind the frontlines, Houthi authorities have engaged in a massive censorship campaign to stifle public awareness of the disease’s spread, keeping shops open and allowing Ramadan festivities to continue normally through April and May even as new obituaries increasingly flooded Yemeni social media and reports of a surge in burials in Sana’a emerged toward the end of last month. The open economy allowed the Houthi authorities’ systemic extortion of businesses to continue unabated, while they also undertook a forceful campaign to collect religious alms from businesses during the holy month. By concealing the extent of the threat, however, the Houthi authorities ensured the spread of COVID-19 in northern Yemen.

Meanwhile, outside Houthi-controlled areas a second front in the war is pitting factions of the anti-Houthi coalition against each other and fracturing southern Yemen, with Yemeni government allies to the east, forces associated with the Southern Transitional Council (STC) to the west, and battles between the two raging in Abyan governorate in the middle. Notably, the STC is in full control of what is meant to be the government’s interim capital, Aden. The Riyadh Agreement, which the two parties signed in November 2019, was intended to end their rivalry, unify them politically and militarily, and facilitate the emergence of functioning public institutions and effective governance in southern Yemen. Instead, the “agreement” became the latest platform upon which to jockey for position, and in continually undermining each other, the parties have collectively robbed people in the south of the public services and protections that a state could provide – such as preparing for the arrival of a pandemic. The STC’s declaration of self-rule for southern Yemen in April would be farcical if it did not so tragically highlight the actual absence of governance in the south. Hospitals’ requests to authorities for supplies to handle COVID-19 patients went unanswered, and as the virus has spread, healthcare centers have shuttered and doctors, lacking personal protective equipment, have turned away the sick.

In Aden, like Sana’a and elsewhere in Yemen, the rising numbers of burials and tributes to the newly dead on social media attest to a virus spreading freely – the World Health Organization (WHO) is now operating on the assumption that full-blown transmission is ongoing in the country – while the lack of available testing makes accurate quantification impossible. Widespread malnutrition and poverty are undoubtedly aggravating factors – ones that are on track to significantly intensify in the near future.

As a soon-to-be-published Sana’a Center research paper will show, the Yemeni market is on the cusp of a precipitous drop in the amount of available foreign currency. Remittances, the country’s largest source of foreign currency estimated at more than US$3 billion annually, are largely sent from Yemeni workers in Saudi Arabia. Tightening labor restrictions on these workers, in combination with a sudden Saudi economic contraction – due to measures aimed at containing COVID-19 and global oil prices plummeting – has the UN projecting that remittances to Yemen could drop as much as 70 percent.

In the past several months there have been increasing warnings that the billions of dollars in foreign support sent annually is also shrinking. In April, the World Food Programme announced food rations in Houthi areas were to be cut in half – impacting some 8.5 million people – while the WHO said it was cutting most of the services it provides in hospitals and care centers, including COVID-19 response operations. The UN announced in May that it was heading for a “fiscal cliff” in Yemen and that its funding deficit was causing three-quarters of its programs in the country to either close or reduce operations. In the process of retraction, these agencies will also shed thousands of Yemeni workers. Meanwhile, the pandemic is creating a far more challenging environment in which to deliver aid for the relief programs that remain, given the reduction in international staff, national staff having their movements restricted by quarantines and their aid agencies’ safety protocols, and global supply chain disruptions.

The impact that the decline in remittances and foreign aid is having on available foreign currency in Yemen, if plotted on a graph, would appear to be a steep downward slope. An actual cliff on this graph will emerge when the US$2 billion deposit Riyadh made at the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden two years ago, which the bank has since been using to finance basic commodity imports, is exhausted. Given the gapping Saudi budget deficit and current cost-cutting campaign, few are expecting Riyadh to match its previous financial assistance to its southern neighbor. As of this writing, there is less than US$200 million remaining of the Saudi deposit and, without replenished foreign currency reserves, the Aden central bank will likely be unable to continue underwriting imports past this summer.

When that happens, traders – in particular commercial food and fuel importers – will have to turn to the market to purchase dollars to pay for orders from abroad. The shrinking supply of available foreign currency, however, means that it will cost increasingly more Yemeni rials to purchase each dollar, and thus the rial’s value will fall. Further downward pressure on the rial’s value will come as the Yemeni government begins issuing tranches of the YR250 billion in new banknotes it recently printed to cover its operating expenses. In a country highly dependent on imports – up to 90 percent of Yemen’s basic foodstuffs come from abroad – a depreciating domestic currency will mean price inflation for most goods. This will be on top of the inflation already caused by pandemic-related global supply chain disruptions. Five years of war and economic collapse have left some three-quarters of the population under the poverty line and even incremental price shifts have outsized impacts – large cost increases will dramatically impact people’s ability to survive. Less foreign currency entering Yemen will also reduce economic activity in general and increase unemployment.

The integrity of the Yemeni rial-based currency system itself will also increasingly come into question. The Houthi authorities’ ban in January this year forbidding new currency banknotes issued in Aden from circulating in areas they control has already spurred divergent exchange rates between northern and southern areas and driven a migration toward the use of Saudi riyals and US dollars to carry out local transactions. The rial’s continued depreciation will further undermine its function as a store of value at all. What business owners will want to accept Yemen’s domestic currency as payment if they expect those bills to be worth less tomorrow?

Thus, in the months ahead it is reasonable to expect a surge in COVID-19 infections accompanied by an acute shortage in access to healthcare, food, water, sanitation and most of the other services that millions of Yemenis receive only from, or through the facilitation of, international aid agencies. Concurrently, prices will spike as a large new slice of the population loses its income source, either because of unemployment or lost remittances. The culmination of these factors will likely propel the humanitarian crisis into dizzying new scales of horror.

To be clear, what is to come is in no way certain, and those in positions of power can choose differently and alter the outcomes. For instance, while the Riyadh Agreement has deep flaws, it is a framework for cooperation which, if entered into with genuine commitment, could facilitate the merger of the Yemeni government and the STC, end the battles across the south and allow a new state apparatus to take shape. The Houthis and the anti-Houthi coalition may still recognize that they are headed for mutually assured pandemic destruction if they do not cease fighting and form a unified front against COVID-19, with this cooperation laying the groundwork for reunifying the bifurcated central bank and other institutions that can begin providing Yemenis with basic services. Perhaps there will be a groundswell among donor countries that will see the international community reinvest in the relief effort and stave off the worst potential humanitarian outcomes. At the same time, international stakeholders could work to prevent further depreciation of the Yemeni rial, advocating strict fiscal policy measures to fight corruption and government waste, and provide the necessary foreign exchange to support import financing in Yemen. These steps are possible. All they take is people in power choosing for them to happen. If they do not, however, and current trends are allowed to play out as projected, it is rational to question whether there will be a future for Yemenis beyond further war, disease and famine in a failed state.

Contents

COVID-19 and the Grave Road Ahead

- In Focus: Yemen’s Medical Sector Struggles to Cope with COVID-19

- Houthi COVID-19 Coverup Unleashes Death, Suffering

- In Focus: Education Under COVID-19 Measures

- UN Evacuates Most International Staff in Sana’a

- Government and STC Forces Clash in Abyan

- Abyan Battles to Determine Fate of the Riyadh Agreement

- Government-STC Power Struggle Simmers in Socotra

Yemeni Govt and Houthis Battle On

- Houthi-Government Fighting Shifts from Marib to Al-Bayda

- Commentary: Al-Bayda Governorate: Too Strategic to be Forgotten

- Houthi Missile Strike in Marib Targets Army Leadership

- Yemeni Government Accuses Houthis of Rejecting UN Cease-Fire Plan

- Commentary: Serious Risks in Saudi Options for Leaving Yemen

- In the United States

- Other International Developments in Brief

Plastic sheeting limits contact between staff and customers at a pharmacy in the Qa’a Al-Ulufi area of Sana’a on May 21, 2020. // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

COVID-19 and the Grave Road Ahead

In Focus: Yemen’s Medical Sector Struggles to Cope with COVID-19

By Rim Mugahed

Yemeni social media accounts filled with obituaries in May as news spread of high numbers of deaths across the country. People relayed stories of being unable to find medicine in pharmacies and questioned how they could protect themselves when a daily wage would barely cover the cost of a face mask, and how families living in a single room could be expected to physically distance from vulnerable or elderly relatives. People also expressed sympathy with doctors who were forced to refuse treatment to sick patients out of fear of infecting their own families. In a video shared on social media, a man in Sana’a prepared to pick up a body left in a shop for two days because local authorities refused to collect it. He asked a question shared by many Yemenis: If a superpower, the United States, has been unable to deal with this pandemic, how will Yemen cope?

Yemen was one of the last countries in the world to report the presence of COVID-19, announcing the first case on April 10. By the end of May, all of Yemen’s 38 hospitals designated for COVID-19 hospitals were full,[1] yet the internationally recognized Yemeni government had officially confirmed only 323 cases of coronavirus, including 80 deaths in areas it controls,[2] while Houthi authorities had confirmed just four cases, including one death in Houthi-held territory.[3] These figures are almost certainly a vast undercount given the country’s chaotic response to the pandemic, especially considering the apparent concealment[4] of cases in Houthi-controlled territories and severe lack of testing.[5] For a country of close to 30 million people, at the end of May the UN reported that Yemen had 675 intensive care unit beds, 309 ventilators and six labs with testing capacity for COVID-19.[6] The Sana’a Center spoke with doctors and medical professionals across Yemen about the challenges of responding to the coronavirus pandemic in a health system which the UN said in May had, in effect, collapsed.[7]

Aden: An “Infested City”

The Yemeni government’s coronavirus committee declared Aden an “infested city” on May 11 due to rising numbers of coronavirus cases and other infectious diseases.[8] Heavy flooding in Aden in April led to sewage flowing through the city and left behind breeding grounds for mosquitoes, which spread diseases. Dr. Mona Mukred, a pharmacist at Al-Jumhuriyah Teaching Hospital, one of Aden’s biggest hospitals, said the floods led to a sharp increase in infections and deaths from malaria, dengue fever and chikungunya, which are endemic in the city and display similar symptoms to COVID-19.[9] She said many people distrust large hospitals due to their poor reputation and because they are unprepared to receive COVID-19 cases. They prefer to visit small health clinics or dispensaries within large hospitals, but Dr. Mukred said these smaller facilities lack testing capacity or medical equipment. Al-Jumhuriyah Teaching Hospital has a small isolation and examination unit able to receive only a few suspected COVID-19 cases at a time.

A vendor wears a face mask while waiting for customers at Al-Taweel market in Crater, Aden, on May 23, 2020. The Yemeni government’s coronavirus committee declared Aden an “infested city” because of rises cases of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases. // Sana’a Center photo by Ahmed Al-Shutiri

A surgeon at May 22 Hospital in Aden, Dr. Iyad, said neither public nor private hospitals were even minimally prepared to deal with COVID-19 cases due to a lack of equipment and supplies. When the first deaths from COVID-19 were announced in Aden on April 28, several hospitals closed as staff walked out because they did not have personal protective equipment (PPE) or resources to treat the disease.[10] Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) took over management of the COVID-19 treatment facility at Aden’s Al-Amal Hospital on May 7; the facility is the only dedicated treatment center for COVID-19 in southern Yemen. Dr. Iyad said Al-Amal Hospital had only seven ventilators.

Dr. Iyad said he had equipped a small apartment with an oxygen cylinder to treat a friend with COVID-19, but another friend had died because no beds were available in the intensive care units at Al-Amal Hospital or Al-Jumhuriyah Hospital. Some people delay seeking treatment until they are no longer able to breathe, Dr. Iyad said, in part because of the similarity of COVID-19 symptoms to those of other diseases such as malaria and chikungunya. No laboratory in Aden is able to test for chikungunya, he added, despite the prevalence of the disease.

Dr. Iyad’s concerns were echoed by MSF, which said many people arriving at Al-Amal Hospital were already suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome, at which point it was difficult to save them.[11] This suggested many people were sick or dying at home, MSF said, noting a sharp increase in burials in Aden. The number of healthcare professionals being treated at Al-Amal Hospital, including MSF staff, indicated the outbreak was widespread, MSF said. The people dying of COVID-19 at Amal Hospital were mostly men between the ages of 40 and 60, MSF said, a younger demographic than seen in COVID-19 fatality rates in other countries, possibly because older sufferers were dying at home instead of seeking treatment.[12]

Private hospitals in Aden are refusing to admit patients with suspected COVID-19 and some public hospitals have closed, Dr. Iyad said. He and Dr. Mukred said the refusal by medical professionals to treat suspected COVID-19 cases violated medical ethics and would have catastrophic consequences, but that it was understandable as staff were not provided with PPE. Authorities also ignored requests from doctors to provide other equipment – such as oxygen cylinders to treat the disease before it progresses to a need for ventilators – and spaces to treat COVID-19 patients, Dr. Iyad said. In the absence of government support, youth activists in Aden launched a campaign in the city in May to provide oxygen cylinders to treat people, he added.

Sana’a: Lack of PPE and Denial of Healthcare

Houthi authorities, meanwhile, had confirmed only four cases of COVID-19 by May 29, but social media and WhatsApp groups were filling with reports of friends and relatives dying with symptoms of the disease. The Sana’a Center is using pseudonyms for doctors in Sana’a to protect their identities, due to Houthi authorities’ intimidation of doctors who discuss COVID-19 publicly. Dr. Huda, who works at a hospital in Sana’a, said the Houthi-run health ministry had issued instructions to transfer all patients with chest infections to Zayed Hospital and Kuwait Hospital, but said these hospitals lacked PPE. She said the administration at the hospital she works in had struggled to secure PPE due to shortages worsened by the Saudi-led military coalition’s restrictions on imports to Houthi-held areas and price inflation, while international aid was scarce. The UN says it is approaching a “fiscal cliff” in Yemen and that cash shortages will force vital programs to close, including those critical to fighting COVID-19.[13]

A boy pushes a wheelbarrow through the central market in Tahrir district, Sana’a, on May 21, 2020. // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Dr. Abdullah, an emergency and critical care physician at a hospital in Sana’a, said preparedness had improved, and that staff had access to PPE. He said the Houthi-run epidemiological surveillance committee was tracking coronavirus cases and supervising PCR tests at private and public hospitals. Doctors have requested that PCR testing should be made available at all hospitals, he said; this would ease the issue of hospitals refusing to receive suspected COVID-19 cases because they do not have access to testing and do not have resources to treat the virus.

Dr. Mohammad, an anesthesiologist at a private hospital in Sana’a, said hospitals remained unprepared to treat COVID-19, and doctors did not have PPE. Some medical staff are buying their own face masks, he said, but these are expensive so doctors are being forced to reuse disposable masks. The hospital he works in is refusing to treat any suspected COVID-19 patients due to fear of transmission, he added. While he felt this was inhumane, he said it was a logical response given the high risk of transmission to other patients and staff. Dr. Mohammad said he would be willing to treat any patient if he had the necessary equipment and resources. His hospital has received no assistance from authorities or international organizations, he said.

Taiz: Little Testing or ICU Available

In Taiz, Dr. Abdelmoghni Almasani, the technical director at Shafak isolation center, said there were seven doctors at the facility, only one of whom was an ICU physician. The team was trained by the World Health Organization. The center has 30 beds and eight ICU beds. It is one of two isolation centers in Taiz; the other has just two ICU beds; these facilities are insufficient for a densely populated city experiencing a growing outbreak, he said. The biggest challenge is the lack of testing, Dr. Almasani said: The number of suspected COVID-19 cases has risen, but the diagnoses cannot be confirmed. Patients arriving at the isolation facility with other illnesses are being turned away, in line with international practices, he added. The center’s doctors receive no government support, he said, warning that the healthcare system was unprepared to confront the pandemic and suffered a widespread lack of PPE. Two of his isolation unit’s medical staff have contracted COVID-19, he said.

Hamstrung WHO Response

The World Health Organization (WHO) is operating under the assumption that full-blown transmission is occurring in Yemen,[14] although the numbers of cases announced by Yemeni authorities remains low. Altaf Musani, WHO representative in Yemen, said the agency had been systematically advising, influencing and informing discussions on case declaration and reporting in Yemen, but that under international health regulations, the decision to announce cases rests with national leaders.

Yemen does not have enough resources to clinically respond to the impact coronavirus will have on the population, Musani told the Sana’a Center. “At present we do not even have enough gloves, masks or other personal protective equipment for all doctors and nurses. … We know that what we have is not enough to cover the projected needs of the country,” he said. The WHO is working to procure and deliver supplies, but amid a global shortage of life-saving supplies, the prioritization of Yemen on this global list is in direct proportion to the actual needs signaled by the country itself. Complicating efforts is the $150 million shortfall the agency is facing in Yemen. In response, WHO said it was phasing out incentives to healthcare workers – which had been in place for years to help compensate for irregular civil salaries payments – and cutting back support for supplies for health centers.[15] In the absence of resources, Musani said, WHO is focusing on prevention, ramping up community engagement and awareness activities.

WHO and its partners are helping equip and upgrade isolation units in 38 hospitals designated for COVID-19, of which 18 units are fully operational. It is also supporting 333 Rapid Response Teams in every district in Yemen; each five-person team is responsible for detecting, assessing and responding to suspected COVID-19 cases.

But the odds are not good, Musani said: Yemen is facing “a powderkeg of factors” including low levels of immunity, high levels of acute vulnerability and a fragile health system that cannot handle an additional crisis. “We are doing what we can but of course, all of this is not enough,” he said. “Everyone in Yemen needs to band together to stand a chance against COVID-19 — from authorities to community and religious leaders to teachers, parents and children.”

Rim Mugahed is a sociologist, novelist and non-resident researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. Her work on Yemen includes research into women’s issues, especially pertaining to police and prisons, and transitional justice.

Houthi COVID-19 Coverup Unleashes Death, Suffering

Commentary by Osamah Al-Rawhani

The COVID-19 virus is rapidly spreading in northern Yemen and the response of Houthi authorities – to publicly deny this reality and silence those who contradict them – has ensured vastly more Yemenis will needlessly suffer and die in the months to come. The advance of the virus in Yemen, already plagued by curable diseases, a collapsed health system and weak immunity levels after five years of war, urgently demands a coordinated and comprehensive response between local authorities and international stakeholders. Instead, the armed Houthi movement, under whose control most of the population lives, has pursued a catastrophic strategy of trying to conceal the virus’ spread, created a fear of reporting symptoms and stigmatized the disease.

(The full commentary from Sana’a Center Deputy Executive Director Osamah Al-Rawhani can be read here.)

Children play with a worker sanitizing public spaces against coronavirus in the Tahrir district of Sana’a on May 21, 2020. // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

In Focus: Education Under COVID-19 Measures

by Yasmeen al-Eryani

Education institutions in Yemen were the first to be shut down in the official response to the COVID-19 pandemic in early March 2020. While the first case of COVID-19 was announced on April 10 in Hadramawt and the first death was announced in Sana’a on May 5, schools were ordered to shut down as early as March 15 in Houthi-controlled areas and a day later in areas controlled by the internationally recognized Yemeni government.[16] The decision came quickly and with no instructions as to how best to implement it. Students were not offered any information on the pandemic and how to avoid its spread. Final exams were canceled for all grades and postponed indefinitely for grades 9 and 12 who are still expecting to sit for their general examinations in June.

Interviews with education staff around the country in May painted a clear picture of how COVID-19 is putting an additional strain on a sector that has been eviscerated by more than five years of war. About 2,000 schools have been either damaged, occupied by armed groups or used to house internally displaced people and 256 schools have been destroyed by ground shelling or aerial strikes. Meanwhile, 51 percent of teachers haven’t been paid since October 2016, affecting 10,000 schools in 11 Houthi-controlled governorates.[17] In other parts of the country teachers continued to receive partial and often delayed payments, leading to prolonged teacher strikes. The impact of war on education has resulted in 2 million children out of school. Now an additional 5 million children will receive no schooling for an indefinite period.[18]

According to an interview with a school supervisor overseeing three girls’ schools in Salah district, Taiz – a district under government control sitting near a frontline with the Houthis – education in this area was already severely disrupted.[19] The school supervisor said it has been very difficult to achieve even minimal education objectives during the conflict. Schools were suspended during intense fighting and students suffered psychological trauma, while many teachers continued to work on a voluntary basis with unpaid or partial salaries. The March decision to close schools as students were preparing for their final exams brought everything to a halt.

Similarly in Dar Sa’ad, one of the most underserved districts in Aden, teacher Nassim Ahmed Salem expressed concerns over the shutdown decision, which seemed to come without a proper plan in place.[20] Salem heads the Arman Development Association, which organizes special lessons for children who have dropped out of school and supports children with disabilities and learning difficulties to remain in school. He said children could have been instructed on how to avoid infection before letting them go for the remainder of the academic year, but this opportunity was lost. “The biggest concern now is that these children are going back to work in menial jobs and it may be very difficult to get them back to school after this is over,” he said. There are also no measures to enforce physical distancing in Dar Sa’ad, where children regularly play and gather in the streets in a densely populated area with a high number of IDPs.

In Shabwa it is not much different, according to Hiyam al-Qarmoushi, an official at the office of the Ministry of Education and the head of the Women’s National Committee in Shabwa. School feeding rations were distributed to children for the rest of the semester and the children were let go. Al-Qarmoushi said that while markets and mosques were closed for only two weeks before they resumed their normal operations, measures were swiftly taken to shut down schools for the rest of the academic year. Prior to COVID-19, education in Shabwa was suffering from many challenges.[21] Although schools continued operating throughout episodes of armed conflict, Al-Qarmoushi remarked that young men and boys were dropping out of school at a high rate to join the Shabwani Elite forces, which offer its recruits relatively generous pay. Shabwa also suffers from an extreme shortage of teaching staff, and relies on teachers coming from outside the governorate, resulting in frequent teacher absences.

In Sana’a, the decision to suspend all education institutions came about two months before the first case of COVID-19 was officially reported. The implementation of this measure was very strict and school principals, particularly in private schools, were threatened with severe consequences if they were not fully compliant with the directive, according to Hajar al-Lahabi, a deputy school principal in a girls’ school in Sana’a.[22] Al-Lahabi explained that this was out of concern for the health and well-being of the students. Nevertheless, this is an addition to a sequence of disruptions to education, with recurrent teacher strikes and excessive teacher absences over the past several years. Many public school teachers work part-time in private schools to make ends meet. Unable to force teachers to work full-time without salaries, the Ministry of Education in Sana’a implemented an emergency plan that made it possible for teachers to work part-time. This resulted in a significant reduction in schooling days per academic year – now exacerbated with early school closure. According to Al-Lahabi, many teachers took a conscious decision to resume their work even without pay, driven by a sense of responsibility towards their students. “We know that boys skip school and join the frontlines and we can’t do anything about that, but at least we could help the girls because if they were not in school they would be in the streets selling tissue boxes,” she said. “Now with the shutdown all the kids are out of school and in the streets.”

As for higher education, Nadia al-Kawkabani, an associate professor in the Engineering Department at Sana’a University, said that final-term exams were postponed until August 2020 and university lecturers at the beginning of the shutdown were expected to carry out lessons online using newly assigned emails and WhatsApp.[23] According to Al-Kawkabani, this plan was not successful as many students did not have Internet access and university staff lacked suitable tools and training to carry out remote teaching. Al-Kawkabani said that while classes were suspended, face-to-face university staff meetings were taking place and other forms of life continued as normal with busy markets and mosques. Meanwhile, a university dormitory was turned into a quarantine site for university staff returning from Aden, where they were collecting their salaries.

Certainly, Yemen is not alone in suspending schools; an April 2020 UNICEF situation report on the MENA region’s response to COVID-19 stated that all MENA countries suspended education institutions, impacting over 110 million students.[24] However, four key international agencies have urged governments to mitigate and weigh the health risks posed by COVID-19 against the risks of school shutdown for children in terms of protection from exploitation and domestic violence, and compromising their social and economic prospects that disproportionately affect marginalized groups.[25] Many countries in the region have implemented some form of remote learning; in Yemen this is extremely challenging with merely 30 percent Internet penetration.[26] The ministries of education controlled by the Houthis and government launched remote-learning programs using local TV channels, but the effectiveness of such measures and the ability to reach the majority of the student population in rural areas remains highly questionable.

Yasmeen al-Eryani is a non-resident fellow at Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies where she focuses on educational issues. Al-Eryani is currently a Ph.D candidate in Social Anthropology in Tampere University in Finland, where her research focuses on education practices and experiences during armed conflict in Yemen. She tweets @YEryani

UN Evacuates Most International Staff in Sana’a

In mid-May the UN evacuated more than half of its international staff in Sana’a because of the spread of COVID-19.[27] The UN’s country team in Yemen already consisted largely of local staff when two flights, on May 12 and 17, transported 98 out of the remaining 158 international staff in Sana’a to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. UN Resident Coordinator Lise Grande and several international WFP staff remained in Sana’a, UN officials told The New Humanitarian.[28] While there were plans to rotate in replacement staff, an increased presence of international UN staff in Yemen is unlikely in the near future.

Several dozen international staff were believed to remain in Aden, following the evacuation of others via UN-chartered flights in previous weeks.

Also concerned for the security of its staff, the WHO temporarily paused “all movements, meetings or any other activity” of its staff in Sana’a, Hudaydah, Sa’ada and Ibb on May 9, Reuters reported, citing a WHO directive.[29] On May 11, the restrictions on staff movement had been lifted, the WHO affirmed.[30]

STC fighters gear up to fight pro-government forces at Sheikh Salem village near Shoqra, Abyan, on May 14, 2020. // Sana’a Center photo by Ahmed Mohammed Obeid al-Shutairi

The Struggle for the South

Government and STC Forces Clash in Abyan

Fighting broke out between Yemeni government forces and those loyal to the Southern Transitional Council (STC) in Abyan in May, threatening to plunge southern Yemen into renewed turmoil and endangering their shared fight against the armed Houthi movement. The clashes followed months of simmering tension between the two sides over unrealized progress on the Riyadh Agreement, a power-sharing deal signed in November 2019 that ended their last round of fighting.

Battles broke out on May 11 after government forces began advancing west along the coast from Shoqra toward Zinjibar, the governorate capital under STC control. The coastal advance was halted near Sheikh Salem, east of Zinjibar, while a second offensive saw government forces advance from Khanfar district and pass through Al-Taryeh to Ja’ar, north of the city of Zinjibar. STC forces have generally maintained defensive positions, halting the advances of pro-government troops north and east of Zinjibar. In particular, Security Belt forces and other units aligned with the secessionist group still hold the 7 October base, the governorate’s largest military base, near Al-Hussn, north of the governorate capital.[31] A temporary truce was struck on May 18 to open the road between Shoqra and Zinjibar but the lull lasted only hours before renewed fighting cut the coastal highway.[32]

To bolster troops based in Shoqra, the Yemeni government brought in forces from Ataq in neighboring Shabwa governorate, Marib and Hadramawt. In response, the acting head of the STC in Aden and former governor of Hadramawt Ahmed bin Breik threatened to send forces to counter any offensives in Wadi Hadramawt, Shabwa and Abyan.[33] Meanwhile, forces loyal to the STC were redeployed from Aden, Lahj and Al-Dhalea governorates to Abyan.

After fighting broke out, STC President Aiderous al-Zubaidi, who is currently based in the UAE, called on the group’s supporters to “defend [the] dignity of and independence” of the South.[34] A more inflammatory call to arms came from STC deputy chairman and militant Salafist Hani bin Breik, who played a major role sparking the August 2019 Aden fighting by calling for a march on the presidential palace to overthrow what he termed the pro-Islah government.[35] On May 18, Bin Breik issued a fatwa on Twitter permitting the spilling of the blood of those attacking the South.[36] The Yemeni government’s embassy in the United States, meanwhile, issued a statement May 11 saying that it was the army’s duty to confront any “armed rebellion” and restore any undermined government institutions.[37]

On May 20, an STC delegation led by Al-Zubaidi arrived in Riyadh. The visit of the STC chief to the Saudi capital, where President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and much of the Yemeni government is based, followed an invitation by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman for talks aimed at ending the southern infighting.[38]

The governorate experienced a brief lull in fighting after a local committee negotiated a cease-fire starting May 24 to coincide with the Eid al-Fitr holiday marking the end of Ramadan, but fighting resumed the next day. At least 45 people had died in the clashes as of May 26, including the commander of the government’s 153rd Brigade, General Mohammed Saleh al-Aqili, according to Yemeni outlet Al-Masdar.[39]

STC forces positioned along the Abyan coast prepare for battle against pro-government forces on May 14, 2020. // Sana’a Center photo by Ahmed Mohammed Obeid al-Shutairi

Abyan Battles to Determine Fate of the Riyadh Agreement

Commentary by Hussam Radman

Besides halting the current military escalation, the Saudis are seeking to convince the STC and the Yemeni government to resume negotiating the Riyadh Agreement. According to local media, Riyadh recently submitted amendments that would synchronize political and security aspects of the accord. The calls for deescalation have been positively received among the STC leadership and the dovish faction of the government, led by the prime minister and representatives of the socialist and Nasserist parties, according to political sources within the government and STC. Meanwhile, government hawks, which advocated for restarting conflict to prove their military strength before any renegotiation of terms with the STC, appear to oppose accommodation before cementing gains on the ground.

(The full commentary by Sana’a Center Research Fellow Hussam Radman can be read here.)

STC forces positioned at Sheikh Salem village, Abyan, prepare to fight pro-government troops on May 14, 2020. // Sana’a Center photo by Ahmed Mohammed Obeid al-Shutairi

Government-STC Power Struggle Simmers in Socotra

Local authorities on the island of Socotra prevented a UAE ship from docking at the main port on May 14, prompting a local power company run by an Emirati businessman to cut electricity on the island. The Socotra local authority suspected the ship may have been transporting weapons to pro-STC elements on the island.[40] The standoff followed tension between the pro-government local authority, led by Socotra Governor Ramzi Mahrous, and pro-Emirati elements surrounding an STC attempt to implement its self-rule declaration in the governorate at the end of April. Fighting between pro-government and STC-aligned forces centered in Haybat, a mountainous district 20 kilometers outside the governorate capital Hadebo, before a May 1 agreement to halt fighting gave coalition and government forces responsibility for securing Hadebo and local authority facilities; both STC and government-aligned forces agreed to remove checkpoints and military vehicles.[41] In the days following the clashes, Saudi Arabia sent additional troops to the island.[42]

The UAE, the main backer of the STC, has worked since the beginning of the conflict to cement its presence on the archipelago strategically situated off the Horn of Africa. It has established proxy security forces in Socotra similar to other Emirati-backed forces in mainland Yemen, while also expanding its soft power influence through offering islanders visa-free access to the UAE, financially assisting fishermen, building infrastructure in the capital Hadebo, among other activities.

Yemeni Govt and Houthis Battle On

Houthi-Government Fighting Shifts from Marib to Al-Bayda

Clashes between Houthi movement and pro-government forces were witnessed across multiple governorates in May, with the focus of fighting shifting to Al-Bayda as violence receded in Marib compared to the intensity of previous months.

Fighting in the governorate was focused in the Qaniyah border region, where an intersection of main roads connects two frontline areas: Al-Abdiyah district in Marib and Radman al-Awad district in Al-Bayda. Here, pro-government forces had begun pushing into Al-Bayda from Marib to the north in April in an effort to ease pressure on other fronts. The Houthis’ forces made advances in Radman al-Awad district toward Qaniyah, seizing back areas lost in previous weeks of fighting, while the Saudi-led coalition carried out airstrikes in Qaniyah and Al-Suwadiyah district to the south.[43] On May 8, the Houthis announced that special forces commander Mohammed Abdel Karim al-Homran had been killed in fighting in the area. According to The Associated Press, Al-Homran had close ties to Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi and was part of an elite unit that had received training from the Iran-backed Lebanese militant group and political party, Hezbollah.[44] By the third week of May, violence had receded compared to levels seen earlier in the month.

The increased violence in Al-Bayda comes as the Houthi movement contends with the threat of an uprising from the governorate’s tribes. At the end of April, Yasser al-Awadi, a local sheikh and member of the General People’s Congress (GPC), issued an ultimatum for the Houthis to respond to demands aimed at providing justice for Jihad Al-Asbahi, the daughter of pro-government Brigadier General Ahmed Mohammed al-Asbahi, who was killed by Houthi forces during a raid on her father-in-law’s house in Al-Taffah district on April 27.[45] A visit by a Houthi delegation to tribes in the governorate and mediation efforts by Oman have thus far failed to resolve the issue. As the tribes’ demands went unmet, the Houthis sent reinforcements to Al-Bayda’s Al-Suwadiyah district.[46] Antipathy among Al-Bayda’s tribes toward the Houthi movement also stems from the group’s association with the Zaidi Imamate. Prior to the overthrow of the Imamate in 1962, Zaidi rulers had at various points in Yemen’s history mobilized northern tribes to invade Al-Bayda, carrying out violence and looting against local tribes.[47]

Marib, where Houthi forces have made major advances into government-held territory in 2020, witnessed a decrease in frontline movement and fighting intensity during the month of May. This change is likely resultant from the Houthi mobilization of forces toward the Qaniyah border region of Al-Bayda.

Fighting remained most active along Marib’s Serwah front, with Houthi forces defending the strategic Mount Haylan and Al-Makhdara mountain vantage points from government forces. Meanwhile, clashes continued near the government’s Kawfal military base, one of the last major defensive points on the road to Marib city and the site of hostilities since February.

Al-Bayda Governorate: Too Strategic to be Forgotten

Commentary by Maged Al-Madhaji

Al-Bayda is often forgotten. It is a vast area of Yemen where little is visible other than poverty and powerlessness, which have worsened during the war. It generally receives little attention among Yemen observers and monitors, except when it comes to Al-Qaeda. Recently, however, Al-Bayda has emerged as a central arena in the battle between the Houthi movement and its opponents.

Al-Bayda borders eight other governorates: Shabwa, Al-Dhalea, Abyan and Lahj to the south, and Marib, Sana’a, Dhamar and Ibb to the north. Its strategic location, providing access to many areas of the country, makes Al-Bayda decisive to the current conflict between the Houthis and the government.

The Houthis, thanks to their military strength, secured control of the governorate in 2015 despite initial local resistance, which was crushed because it was scattered and received no support. For years, there was little conflict in the governorate. Initially, the Houthis relied on their alliance with the General People’s Congress and former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had great influence on tribes there. Later, they reached agreements by force with local tribes to avoid engaging in open conflicts in exchange for letting the tribes manage their own affairs.

The Houthis’ strategy in dealing with Al-Bayda tribes is based on two elements: mobilize supporters from among tribes (particularly Hashemites who, like the Al-Houthi family, trace their lineage to the Prophet Mohammed) and render neutral tribes that are not loyal to them. This arrangement has guaranteed that tribal blocs that are not loyal to them are neither hostile toward them nor supportive of the government, and it allows the Houthis to freely move in the governorate and control it.

One of the most important agreements the Houthis struck was with the Al-Awad tribe, which is large, prominent in the governorate and traditionally hostile to the Zaidi imamate. Sheikh Ahmad Abdo Rabbu al-Awadi is one of the tribe’s most notable members. He emerged as a charismatic leader during the Yemeni civil war after the 1962 revolution that overthrew the Zaidi imamate and played a decisive role in ending the siege imposed by the royalist forces on Sana’a in 1968.

The Houthis also reached an accord with the combative Qifa tribes, which are known for their opposition to authority and engaged in a bloody conflict against the Houthis at the beginning of the war. This confrontation with the Houthis was costly, and the government appeared unwilling to provide the necessary support – it did not even prioritize Al-Bayda in its strategy for confronting the Houthis. As a result, the Qifa tribes eventually settled with the Houthis.

Neutralizing the Qifa tribes after their bloody conflict was significant, but the other challenge for the Houthis was dealing with the Al-Awad tribe via a deescalation deal. Al-Awad tribe extends into Marib and is present in Al-Abdiyah district adjacent to Al-Bayda. The tribe’s bloc in Marib maintained a hostile position against the Houthis while the tribe’s bloc in Al-Bayda remained neutral and away from the conflict. Likewise, tribes in Al-Bayda’s Al-Malagem and Al-Sawadiyah districts did not want to engage in a futile conflict with the Houthis without any guarantees that the government would provide continuous, unqualified support, and thus remained neutral. So, the tribal situation remained under control, except for the Humaiqan, which includes a Salafi presence, and has fought the Houthis ever since the war erupted on ideological grounds.

Meanwhile, the Houthis have managed an interesting relationship with the Islamic State (IS) group, which has a presence and positions in Al-Bayda. There appears to have been an implicit agreement between the groups to not attack each other. While cautious of one another, the situation has remained stable with no confirmed reports of IS targeting Houthi fighters or vice versa. IS, however, has attacked the national army. For example, it detained four people in the Yakla area because they were headed to join the army and broadcast footage of their execution on September 11, 2018.

The Houthis’ relationship with Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) does not seem as stable, though the Houthis have tended to avoid targeting it, focusing on maintaining calm. Al-Qaeda and IS camps are present in isolated areas of Al-Bayda, specifically in mountainous ranges between Al-Bayda and Abyan and Shabwa governorates. Al-Qaeda also has a limited presence in the district of Wald Rabi’. Some Al-Qaeda members belong to conservative tribes and this has helped the group operate within the governorate’s social fabric. Meanwhile, IS, with its hardline beliefs and many non-Yemeni members, is viewed as a stranger, and the group’s relationships with tribes have witnessed extreme and regular tensions.

Al-Bayda governorate is implicitly and unofficially divided into two blocs. One is centered around Al-Bayda city and its surroundings, and another around the city of Rada’ and its surroundings. Rada’s particularity is that it is a sectarian frontline as its tribes are Sunni while its tribal neighbors in the Dhamar governorate belong to the Zaidi sect of Shia Islam. These tribes, while not necessarily religious, have a strong sense of religious identity. This was also formed in part by past invasions of Al-Bayda by Zaidi imams, which have been immortalized in Al-Bayda tribes’ zawamel, the folk songs that inspire fighters ahead of battle.

Therefore, Al-Bayda represents more hostile territory to the Houthis compared to most other governorates. Except for some communities with a Hashemite identity, including Riyam, outside Rada’, and Al-Saqqaf in Al-Sawadiyah, the majority of residents do not have anything in common with the Houthis. Rather, there is a history of enmity and subjugation associated with Zaidi rulers.

It is notable that the Houthis, after entering Sana’a in September 2014 and while still on good terms with President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, marched toward Al-Bayda to seize it before heading to Aden, Taiz, Hudaydah or any other governorate. The Houthis’ military prioritization of Al-Bayda revealed the governorate’s strategic importance as well as the Houthis’ awareness of Al-Bayda’s history of rebellion against the center and lingering animosity. Hence, subjugating Al-Bayda was a priority. Doing so also brought the Houthis into an alliance with Saif al-Qabli, a prominent sheikh now living in Oman who fought with the Imamate during the civil war between the royalists and republicans.

Al-Bayda Becomes Key to Protecting Marib

Battles in Al-Bayda have been fiercest in the area of Qaniyah, in the district of Radman al-Awad bordering Marib governorate. These battles began in 2018, but have increased in intensity and frequency since government forces began advancing slightly on this front in April. The government offensive coincided with Houthi forces’ pressure on frontlines in Marib, and thus the Al-Bayda front became important in blunting the Houthis’ surge toward Marib by keeping them busy in Qaniyah.

There are also battles in the Humaiqan area, part of Al-Zahir district adjacent to Lahj governorate, and in Mukayras district adjacent to Abyan governorate. The continuous battles since 2015 in the Humaiqan area tend to resemble gang warfare against the Houthis more than a comprehensive military confrontation. The Qifa area of Al-Bayda, specifically surrounding Yakla, has seen a fragile, intermittent calm.

However, the government thus far has failed to achieve a major breakthrough in any Al-Bayda battles because there is no strategy to mobilize tribes and push them to rebel against the Houthis. This is due to several factors, most notably the tribes’ distrust of the government and coalition to provide real support, fearing that they will be left again to face the Houthis alone.

Recent events, however, between the Al-Awad tribe and the Houthis have threatened to explode into a full tribal rebellion. Tensions between the two in 2018 reemerged when Houthi forces killed a woman, Jihad al-Asbahi, from a neighboring tribe during a raid on her home in April. The incident sparked anger and tension; in Yemeni society and according to tribal customs, killing women is a shame requiring justice no matter the cost.

Al-Ashabi’s family appealed to the Al-Awad for help in receiving justice. This incident encouraged calls for rebellion against the Houthis – one that the coalition and the government failed to create and that the Houthis brought upon themselves. Still, it represents the best opportunity to change the formula in Al-Bayda and creates a real challenge to Houthi control of the governorate.

The Houthis have displayed flexibility – negotiating rather than resorting to swift military action – when dealing with this case for several reasons. First, this case socially exposes them for committing a grave violation according to tribal society. Second, the Houthis need Al-Bayda to stay calm as its strategic significance is more important than any temporary display of prestige and power. As of the end of May, tribal mediation was continuing between Al-Awad and the Houthis to reach a settlement, or at least postpone any clash.

While it is not assured that a tribal rebellion will erupt against the Houthis or that the government will succeed in advancing from the outskirts of Al-Bayda to its heart, what is certain is that the Houthis do not want to risk losing this governorate. For the government, taking Al-Bayda would represent a turning point in the conflict. Al-Bayda overlooks the governorate of Dhamar, south of Sana’a, and if the government controls Al-Bayda, it will be able to pressure, and perhaps cut, Houthi supply lines toward fronts in Ibb, Taiz and Al-Dhalea. Al-Bayda would also give the government a direct path to join the Damt front in Al-Dhalea governorate and pressure Houthi forces there. It also would block the Houthis’ chances of threatening the southern governorates of Shabwa and Abyan. The uniquely strategic location of Al-Bayda grants whoever controls it the keys for escalation and deescalation on open fronts in eight different governorates. But controlling it, as both sides know, requires strategies responsive to tribal interests.

Maged Al-Madhaji is a co-founder and executive director of the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. He tweets at @MAlmadhaji.

Houthi Missile Strike in Marib Targets Army Leadership

On May 26, a Houthi missile strike hit Yemeni army headquarters in Sahn al-Jinn, between Marib city and Marib al-Wadi, as a meeting of the senior army leadership was taking place. Yemeni government Minister of Defense Mohammed al-Maqdishi and army chief of staff Major General Saghir bin Aziz both survived the missile strike, although the chief of staff’s son and six others were killed.[48]

The Houthis have previously targeted army camps in Marib, with a January 2020 strike killing 111 soldiers.[49] An investigation by Yemeni outlet Al-Masdar revealed that Houthis have been utilizing their control of the country’s telecommunications network to aid their military operations in Al-Jawf and Marib. Locals claimed that blocked mobile networks would briefly reconnect before missile bombardments, leading to speculation the group was using phone location data to guide the strikes.[50]

Yemeni Government Accuses Houthis of Rejecting UN Cease-Fire Plan

Even as battles raged on the ground, on May 23 the Yemeni government announced that it had accepted the UN’s proposed nationwide truce, including a prisoner exchange and the reopening of Sana’a airport, but Houthi authorities remained cool to the proposal.

The announcement, made on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Twitter account, quoted Foreign Minister Mohammed al-Hadrami as saying that the UN envoy’s plan agreed to by the government included a cease-fire, a joint coronavirus task force, full opening of roads and re-opening Sana’a airport for international flights, payment of all public sector salaries, the release of all prisoners and further talks, adding: “In turn, the Houthis rejected it!”[51] While the armed Houthi movement has not publicly rejected the UN proposal, diplomatic sources confirmed to the Sana’a Center that the group’s stance has been the main obstacle preventing an agreement.

The UN, through its envoy Martin Griffiths, continued to mediate among the warring parties in May, though progress was slow during the Islamic month of Ramadan. Griffiths has been pushing a nationwide cease-fire since the end of March, and on April 10 he announced that the UN had distributed a revised plan to the warring parties. Along with a halt in the fighting, the plan contains economic and humanitarian initiatives and an agreement to resume the political process.[52] The Houthis, however, released their own peace plan in April, demanding the withdrawal of coalition forces, the lifting of restrictions on the entry of goods and people into Houthi-held territory and Saudi agreement to pay reparations as a precursor to any cease-fire deal.[53]

During a May 14 briefing to the UN Security Council, Griffiths said “significant progress” had been made in negotiations on the UN plan, particularly on the nationwide cease-fire component of the deal. However, he pointed out that all aspects of the deal needed to be agreed upon before it could be announced. The envoy also stressed the importance of humanitarian and economic measures outlined in the proposal in helping Yemen deal with COVID-19.[54] Griffiths held talks with Houthi spokesperson and chief negotiator Mohammed Abdel Salam on May 22.[55]

The mission of negotiating a nationwide cease-fire was made more complex with the outbreak of renewed fighting in May between the Yemeni government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC). On May 14, the Security Council called on both sides to deescalate military tension and return to the Riyadh Agreement while singling out the STC “to reverse any actions challenging the legitimacy, sovereignty, unity or territorial integrity of Yemen, including the diversion of revenues.”[56] (See: STC Claims Aden Revenues, Adding to Government’s Economic Woes) The UN envoy’s position has been that the STC should be included as part of the Hadi government delegation in future peace talks, as laid out in the Riyadh Agreement.

UN Security Council Plans Resolution to Support Yemen Cease-Fire Deal

If a cease-fire agreement is reached, the UN Security Council is expected to negotiate a resolution supporting the UN envoy’s plan. According to a diplomatic source, Griffiths requested that the Security Council formalize its backing for the prospective accord during a closed-door meeting of the council. A new resolution would likely include calls for the warring parties to de-escalate tension and commit to a nationwide cease-fire. Negotiating resolutions on Yemen has been challenging given the Saudi worry that any outcome that is binding would undermine UN Security Council Resolution 2216, which Riyadh uses as the justification for its military intervention in Yemen. However, a new resolution would be unlikely to challenge or change 2216, given Riyadh’s proven ability to leverage relations with UNSC member states to shape Council outcomes in line with Saudi objectives.[57]

Aside from technical renewals of mechanisms such as the UN sanctions regime and the United Nations Mission to Support the Hudaydah Agreement, the last Security Council resolution passed on Yemen was the endorsement of the Stockholm Agreement in December 2018. Although the Security Council, particularly its five more powerful permanent member states, is often touted as being united on the Yemen file, the last negotiation on Resolution 2511, passed in February 2020 to extend the UN arms embargo against the Houthis and renew the mandate of the Panel of Experts for another year, revealed that differences remain.[58] The United States is likely to champion references to Iran, having actively accused it in the past of providing arms to the Houthis.[59] Russia, on the other hand, warned the Council once again in February that singling out blame would not be tolerated in future resolutions.[60]

Hudaydah Cease-Fire In Peril As UN Monitors Sent Home

A truce governing Hudaydah appears to have completely broken down as the cease-fire monitoring mechanism in the port city ceased to operate and most UN mission personnel left the country while diplomatic efforts have shifted toward negotiating a nationwide halt in fighting. Fighting escalated in the governorate during May with both sides shelling and sniping across the frontlines. Main lines of contact extended from Al-Durayhimi and Hays district to the northeast part of Hudaydah city.

The UN Redeployment Coordination Committee (RCC) charged with monitoring the cease-fire has not operated for months. In March, the Yemeni government suspended its participation in the RCC after a member of the government monitoring team, Colonel Mohammed al-Sulihi, was shot, allegedly by a Houthi sniper. Al-Sulihi died in April.[61] Martin Griffiths, the UN envoy, told the UN Security Council in April that the cease-fire in Hudayah was being violated daily and the UN-led RCC had in effect “ceased to function” since the incident.[62]

By early May, at least some of the UN Hudaydah mission had been moved to Oman. On May 4, UN Under-Secretary-General for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs Rosemary DeCarlo tweeted a photo of the UN ship that previously hosted meetings of the RCC, along with thanks to Omani Sultan Haitham bin Tariq for assisting in the “temporary repositioning of some mission personnel.”[63] The ship, the Antarctic Dream, docked in Salalah, where the UN arranged for the repatriation of RCC personnel to their home countries, according to a source within the UN who spoke with the Sana’a Center. The head of the UN mission, General Abhijit Guha, who according to the same source has remained in Hudaydah along with a handful of aides, later told the Security Council at a closed meeting on May 14 that he wants to reopen a line of communication to the parties in the next two to four months.

A Yemeni diplomatic source told the Sana’a Center that the government has prepared a list of demands that must be met before it would rejoin the RCC. These include an investigation of the sniping attack, the relocation of the UN headquarters in Hudaydah (currently based in converted villas in Houthi-held territory) to a neutral location and free movement for UN personnel in the city.

Meanwhile, UN diplomatic efforts through the Special Envoy’s office have shifted toward brokering a nationwide cease-fire, with a particular emphasis on preventing a destructive battle for Marib city, from its previous focus on demilitarizing Hudaydah as part of the Stockholm Agreement. Indeed, the December 2018 deal, which included a cease-fire to stop a government assault on Hudayah city, a prisoner swap and a statement of understanding on Taiz, appears dead, as neither side has shown a real commitment to honoring the terms agreed to in Sweden. The UN also seems to have accepted this reality and is now focusing on including a broader cease-fire and prisoner exchange component in a future deal that would update and supersede the Stockholm Agreement.

A barber wears gloves and a face mask in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic as he cuts a young customer’s hair ahead of the Eid al-Fitr in the Al-Bonniyah neighborhood of Sana’a on May 21, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Other Developments in Yemen

Economic Developments

STC Claims Aden Revenues, Adding to Government’s Economic Woes

After declaring self-rule at the end of April, the Southern Transitional Council (STC) moved in early May to try and secure locally generated revenues from the southern coastal city of Aden. This included collecting Aden Port revenues, which are essentially customs, import taxes and port service fees.[64] The STC shuttered the Central Bank of Yemen office at the port and confiscated existing customs and import tariff revenues, according to a Sana’a Center financial source. The port revenues are being deposited in an account held at the Aden-based National Bank of Yemen, also known as Al Ahli Bank.[65] According to an estimate provided by one government official, the port generates a daily average total between 200 to 300 million Yemeni rials (roughly between US$282,000 to $483,000, based on an exchange rate of YR708 per US dollar in Aden at the end of May).[66]

On May 4, the STC announced the establishment of the Supreme Economic Committee with Abdel Salam Humaid appointed as the head of the committee. Three days later, Humaid asserted that a number of public economic institutions had opened their own accounts at Al Ahli Bank, as requested by the STC and its Supreme Economic Committee.[67] Among those said to have opened accounts are Aden Refinery Company (ARC), the local Aden branch of the Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC), and local customs authorities located at Al-Mualla and Aden Free Zone, among others.[68]

Losing revenue from Aden leaves the government in an even more precarious economic position following the sizable reduction in crude oil revenues caused by the huge drop in global oil prices that began in March this year.[69] In 2019, the government was exporting crude oil at an average price of $65 dollar per barrel and accumulated an estimated total of $600 million in crude oil export revenues by the end of the year.[70] Global oil prices have increased marginally since the sudden fall in March, and as of May 26, 2020, the price of Brent Crude was $35 dollars per barrel. Current crude oil export revenues leave the government with little net revenue after covering the operating costs for state-run oil companies SAFER and PetroMasila. SAFER oversees Block 18 in Marib, which resumed crude oil exports in the second half of 2019 via Nushayma terminal in Shabwa. PetroMasila runs Blocks 10 and 14 in Hadramawt, which resumed intermittent crude oil production and export activities in 2016. Given the government’s dependency on hydrocarbon revenues as its main source of revenue, the drop in global oil prices will leave it struggling to prevent a further widening of its accumulated budget deficit gap.[71]

Newly Printed Notes Could Further Devalue Rial

The internationally recognized government appears to have responded to the revenue it has lost from Aden and crude oil exports by ordering the delivery of more newly printed Yemeni rial notes, with some estimates claiming YR250 billion arrived to Aden during the third week of May.[72] However, it is unlikely that the notes will be immediately issued by the government-run Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Aden. According to one Yemeni banking official, new banknotes generally are placed in a designated vault and then fed gradually into the total currency supply, depending on how much already is in circulation.[73] However, without an offsetting increase in economic activity, issuing additional currency will put further downward pressure on the Yemeni rial’s value in areas under government control, where there has already been a recent influx of newly printed banknotes because of the ban on such in Houthi-controlled territory since January.[74] Printing more money could also have a notable inflationary impact in areas outside the control of the Houthis.[75]

Since relocating the central bank headquarters from Sana’a to Aden in 2016, the Yemeni government has tried to cover budget shortfalls through printing some 1.7 trillion in new banknotes.[76]

Saudi Deposit Below US$200 Million, Rapid Currency Depreciation Looms

Less than US$200 million remains from the original US$2 billion deposit that Saudi Arabia earmarked for the internationally recognized Yemeni government in March 2018, according to an Aden-based senior Yemeni banking official who spoke with the Sana’a Center.[77] Since June 2018, the government-run CBY in Aden has been using funds allocated from the Saudi deposit to underwrite the import of essential food commodities – specifically rice, wheat, sugar, milk and cooking oil.[78] Later, essential medicines were added to the list.[79] The government’s last public announcement regarding the allocation of funds from the Saudi deposit came on April 1, when it stated that the CBY in Aden had issued US$127 million worth of letters of credit.[80]

The Saudi deposit has been a major stabilizing force for the Yemeni rial, enabling the government to help meet food importers’ foreign currency demands in a regulated manner. A Yemeni economist told the Sana’a Center that about $80 million per month is needed to cover Yemen’s total food import requirements, with the country importing up to 90 percent of its foodstuffs.[81] A number of importers, however, use Yemeni money exchange companies to secure and transfer foreign currency to pay exporters.

Saudi Arabia – which is currently facing its own budget shortfall due to low oil prices – has not indicated whether it will financially intervene once more when the remaining funds at the CBY are depleted. Given the Yemeni government’s current challenges to independently generate foreign currency, the Yemeni rial can be expected to depreciate rapidly without a significant injection of foreign currency from Saudi Arabia or other external actors. Sana’a Center economists estimate the rial could fall below YR1,000 per US$1 by year’s end; at the end of May the Yemeni currency was trading at YR 602 per US dollar in Sana’a and YR 708 per US dollar in Aden. This would result in severe inflation in the cost of almost all goods purchased locally, which in turn would bring about a rapid intensification in the country’s humanitarian crisis, already considered among the worst in modern history.

Military and Security Developments

AQAP: Ties to US Shootings Raise Fresh Questions

On May 18, the FBI announced that it had succeeded in unlocking the phones of Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani, a Saudi Air Force officer, who opened fire at a US naval air station in Pensacola, Florida on December 6, 2019, killing three sailors and wounding eight others.[82] The broader point of the FBI’s statement, that Alshamrani had been in contact with AQAP, was already largely known thanks to a February video release by AQAP, which featured the shooter’s will as well as messages to the group.[83] What wasn’t known, however, were some of the details. Namely, that Alshamrani had been in contact with AQAP since 2015, and that he later joined the Saudi Air Force in order to carry out a “special operation.”

The FBI statement also suggested that Alshamrani was in contact with AQAP’s media officer, Abdullah al-Maliki, who was recently targeted in a US counterterrorism operation in Yemen. That is an apparent reference to a May 13 drone strike in Marib, which severely wounded Al-Maliki, resulting in the amputation of one of his legs, and killed one other AQAP member.[84] Other news reports suggested that Al-Maliki had been killed in a strike.[85]

There are, however, still three key questions about Alshamrani’s relationship with AQAP.

- Did Alshamrani reach out to AQAP in 2015 or did AQAP recruit him?

- Was Alshamrani a member of AQAP, someone who offered the group his oath of allegiance (bay‘a), or merely a supporter and like-minded individual?

- Did AQAP instruct him on when and what to attack or merely provide advice as he planned his attacks?

These questions are important not necessarily for what they tell us about Alshamrani, but rather for the insights they would provide about AQAP, its inner workings and the current threat it poses. For instance, if Alshamrani reached out to AQAP that is one thing, but if AQAP was actively recruiting individuals to join the Saudi Armed Forces that is something else entirely, and an indicator that instead of being an isolated incident Alshamrani might be representative of a broader trend. Similarly, Alshamrani’s membership status and the level of influence AQAP had over his attack matters greatly. If AQAP was only consulting and providing advice to Alshamrani for an attack he largely planned himself that tells us more about Alshamrani than it does about AQAP. But if AQAP was directing and instructing Alshamrani in what one analyst described as essentially a replay of the Fort Hood attack and the Little Rock shooter, then that would suggest that AQAP’s foreign operational planning has not progressed much over the past decade.[86]

On May 21, three days after the FBI announced the details of the Alshamrani case, another shooting took place at a military base in Corpus Christi, Texas. The suspect, 20-year-old Adam Salim Alsahli, attempted to speed through a security gate at the naval air station, wounding one security guard in the process.[87] The guard managed to raise a barrier in time to prevent Alsahli entering the base. Other guards shot and killed Alsahli, whose social media posts expressed support for AQAP and other terrorist groups. There is, as of yet, no evidence that Alsahli was in contact with AQAP.

Fractures within AQAP

Within Yemen, there continue to be rumors of fractures within AQAP. Mohammed al-Basha, a prominent Yemen analyst, outlined one of these splits in a Twitter thread, describing it as a fracture between AQAP’s top leaders, men including the newly named head of AQAP Khalid Batarfi and Saad bin Atef al-Awlaki – both of whom are on the US’s most-wanted list – and regional commanders Abu Omar al-Nahdi, Abu Daud al-Sayari and Abu al-Walid al-Hadrami.[88]

Not surprisingly, these reports are emerging as Batarfi, who was named as head of AQAP in February, attempts to consolidate control over an increasingly fragmented organization.

Under Batarfi’s predecessor, Qasim al-Raymi, who was killed by a US drone strike in January, AQAP struggled on a number of fronts. The group was unable to replace key figures like Said al-Shihri, Anwar al-Awlaki and Ibrahim Asiri, who were all killed in US drone strikes. Part of this replacement problem was exacerbated by the rise of ISIS in Iraq and Syria, which siphoned off many of the international recruits who in previous years had traveled to Yemen. AQAP also struggled with spies and informants within its ranks. Indeed, according to The New York Times, the US was able to locate and track Al-Raymi thanks to an informer.[89]

Batarfi appears to see his job as one of reorganizing and tightening the ranks. But Batarfi may be moving too fast. He was not a unanimous choice to replace Al-Raymi. At the time, AQAP said that because of communication difficulties not everyone within the organization was consulted.[90]

Among the issues that AQAP’s mid-level commanders have with Batarfi are the recent executions of three alleged spies as well as the removal of some of their colleagues as regional commanders. The group has sent its complaint to Ayman al-Zawahiri, the global head of Al-Qaeda, and requested he intervene.[91]

Other Military and Security Developments in Brief:

- May 17: A British-flagged vessel repelled an attack by pirates in the Gulf of Aden. Stolt Tankers said its ship, the Stolt Apal, was approached by two speedboats 75 nautical miles off Yemen, leading to an exchange of fire between armed guards onboard the chemical tanker and the would-be pirates.[92]

- May 27: An improvised explosive device detonated near a police vehicle in Shibam district, Hadramawt governorate, killing the district security chief, Saleh bin Ali Jaber, along with three fellow passengers.[93]

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

UN Warns Against Stigmatizing African Migrants

The UN expressed concern about rising xenophobia in Yemen fueled by migrants being stigmatized as “transmitters of disease,”[94] as Houthi authorities confirmed on May 5 the first case of COVID-19 in territory they control was a Somali national who had died in a hotel in Sana’a. A laboratory test later confirmed he had been infected with COVID-19.[95] The UN said the man had lived in Yemen since seeking refuge in the country as a child.[96]

Refugees and migrants from the Horn of Africa have continued to enter Yemen throughout the war, trying, but often failing, to reach Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. These journeys have continued during the COVID-19 pandemic, though with decreasing numbers, a humanitarian aid worker in Sana’a told the Sana’a Center.[97]

The World Health Organization and International Organization for Migration said that migrants, as a result of the stigmatization and scapegoating, have been physically and verbally harassed, denied medical care, forced to frontline and desert areas and left stranded without food, water and other essentials.[98]

Other Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments in Brief:

- May 10: Saudi Arabia announced that it would host an online donor pledging conference for Yemen in partnership with the UN on June 2.[99] The event was initially scheduled to be held in Riyadh in April, but postponed until further notice due to international travel restrictions.

- May 17: As part of a coordinated European response, the EU announced it had pledged 55 million euros to support Yemen’s pandemic response.[100]

- May 21: A local staff member of the World Food Programme died from COVID-19, The Wall Street Journal reported.[101]

-

May 28: A first plane, arriving from Amman, landed at Sayoun airport, Hadramawt governorate, part of a government plan to repatriate Yemeni nationals stranded in Jordan, Egypt and India.[102]

International Developments

Serious Risks in Saudi Options for Leaving Yemen

Commentary by Abdulghani Al-Iryani

Saudi Arabia is politically and financially exhausted after five years of conflict against the Houthis. Tired of the 200 million Saudi riyal per day cost of the war, Riyadh offered a unilateral cease-fire April 8 and then extended it two weeks later, part of its attempt to pivot to a negotiated solution after continued territorial losses. Timed with the growing COVID-19 crisis, the recent Saudi cease-fires provided face-saving moral high ground to step back militarily and invited the Houthis to follow. The Houthis, however, were not biting; they ignored the cease-fires and responded with their own peace terms that would amount to a Saudi surrender. Given Houthi intransigence and Riyadh’s increasing desperation over the deadlock, the Saudis appear to be reconsidering their engagement in Yemen in principle.

Two options appear to be under consideration, judging from Saudi Arabia’s actions and the opinions emanating from its “independent commentators”— editors and publishers who float the ideas of senior Saudi officials. One option is to make a deal with the Houthis and let other Yemeni parties fend for themselves, providing enough support to local warlords to keep Yemen in a state of perpetual civil war similar to that of Somalia in the 1990s. Saudi disengagement from Yemen would almost certainly lead to economic collapse, as much of the foreign exchange that keeps the Yemeni economy going comes from the war budget in the form of salaries and patronage payments to tribesmen. This option will be a round-about way of achieving the desired objective of “no victor-no vanquished.” Saudi Arabia would avoid an outright defeat, as there would be no winners in Yemen as it gets ravaged by famine and disease.