US Sanctions Complicate Humanitarian and Financial Landscape

The first quarter of 2025 saw escalating US sanctions against the Houthis. The sanctions, intended to suffocate the Houthis financially, could have a negative impact on Yemen’s already fragile financial system, and threaten to disrupt flows of crucial humanitarian aid and remittances, further destabilizing the economy.

In mid-January, the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned the Yemen Kuwait Bank for Trade and Investment for providing financial support to the Houthis. OFAC accused the bank of allowing the Houthis to exploit the Yemeni banking sector to launder money and transfer funds to their allies, including the Lebanese group Hezbollah. The bank was also alleged to have helped the Houthis establish and finance front companies involved in Iranian oil sales, in coordination with the sanctioned Houthi-associated money exchange Swaid and Sons.

The sanctions had a devastating impact on the bank’s operations and affected the entire sector. The Yemen Kuwait Bank has been effectively disconnected from the international financial system: US-owned financial transfer providers, such as Western Union and MoneyGram, have terminated their relationships, disrupting millions of dollars in remittances, particularly from Yemeni migrants in the Gulf countries. The bank had played a vital role in facilitating humanitarian aid delivery, managing funds for UN agencies, INGOs, local NGOs, and civil society organizations. The sanctions disrupted this critical function, forcing customers to seek alternatives.

Sanctions had already been imposed on numerous senior Houthi officials and entities for their roles in trafficking arms, laundering money, and shipping illicit Iranian petroleum. They include the governor of the Houthi-aligned Central Bank of Yemen in Sana’a (CBY-Sana’a), Hashem Ismail Ali Ahmad al-Madani, accused of facilitating funds transfers from Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force to the Houthi group.

Adding to the financial pressure, the Trump administration redesignated the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) on March 4, reversing the Biden administration’s 2021 rescission of the designation. The decision followed US President Trump’s Executive Order 14175, issued on January 22, citing Houthi attacks on international shipping. In January 2024, the Biden administration had listed the Houthis as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) organization, a lesser designation, in response to the group’s attacks in the Red Sea.

On March 5, OFAC revised its Houthi-related General Licenses under the Foreign Terrorist Organizations Sanctions Regulations (FTOSR) and implemented targeted amendments to close loopholes and enhance enforcement. Specifically, OFAC updated its General Licenses authorizing transactions related to agricultural commodities, medicine, and medical devices, to ensure continued access to essential supplies; noncommercial and personal remittances, to safeguard financial support for Yemeni civilians; and third-country diplomatic missions, to preserve crucial diplomatic channels.

However, OFAC also amended some General Licenses to impose stricter controls. The delivery and offloading of refined petroleum products in Yemen was only authorized until April 4, and only if such products had been loaded onto a vessel prior to March 5. OFAC also explicitly excluded refined petroleum products from the list of goods that can be imported or exported through Houthi-controlled ports and airports. In response to the impending fuel import ban, the internationally recognized government pledged to provide petroleum products and cooking gas to Houthi-controlled areas. However, the effects of the ban are of concern across the country, as government areas have long suffered from fuel shortages and prolonged electricity outages.

Under the FTO designation, persons and entities may face penalties if they knowingly provide “material support or resources” to a group, including currency and financial services. US sanctions effectively prohibit any financial dealings with entities tied to the Houthis, making it difficult for Houthi-linked businesses and banks to access global financial networks such as SWIFT, Western Union, and MoneyGram. The UN previously cited the consequences of this isolation when it asked the CBY-Aden to abandon attempts to consolidate power over Yemen’s financial sector.

The impact on trade, particularly through the Houthi-controlled port of Hudaydah, which handles most of Yemen’s imports, is a major concern. With Yemen heavily reliant on imported food and medicine, the FTO designation, even with its humanitarian aid exemptions, has raised fears of cuts and delays in aid distribution as organizations try to navigate the sanctions.

Adding to the dilemma, the US temporarily suspended USAID funding, depriving Yemenis of access to vital aid programs. The World Food Programme (WFP), which received more than US$700 million a year from USAID, was forced to suspend dozens of projects. In early February, the US temporarily halted food aid to the WFP as part of a pause on Title II funding for US farmers under the Food for Peace program. This interruption directly impacted the WFP’s work in Yemen, where 64 percent of the population cannot meet minimum food requirements. The halt in food aid was part of a broader re-evaluation of foreign aid under Trump’s “America First” policy, in which the WFP was instructed to suspend dozens of US-funded grants.

Some Yemeni economists have suggested the Houthis’ FTO designation could help the government consolidate authority over the economy, as banks will have to deal with the CBY-Aden to avoid sanctions. Banks in areas under Houthi control could see the freezing of assets, accounts, and foreign reserves in international correspondent banks unless they can prove they have no relation to the Houthis.

Eight banks announced their intention to relocate their headquarters to Aden in mid-March, a move the CBY-Aden welcomed, saying it would help protect the banks from the consequences of the Houthi terrorism designation. However, the CBY-Sana’a condemned the relocations, attributing them to Saudi and Emirati influence. There have been reports of travel bans for bank employees trying to leave Sana’a and threats to detain those who try to flee to government-controlled areas.

If the sanctions are strictly enforced, they could limit the Houthis’ ability to conduct international financial transactions. But the group has demonstrated adaptability in the past, and will likely increase its reliance on money transfer networks, which are harder to monitor.

Food Security Worsens

Yemen is grappling with increasing food insecurity, driven by the ongoing conflict, economic collapse, and reduced aid. In its latest Yemen situation report, the World Food Programme (WFP) indicated that 62 percent of the population was facing inadequate food consumption in February, up more than 15 percent from last year. The report attributed the deterioration in food security to the increase in food prices in government-controlled areas and the limited assistance delivered in Houthi-controlled areas. The lack of income-generating opportunities across Yemen has compounded these issues.

The latest Joint Monitoring Report highlighted this crisis, warning that Yemen’s food security situation is continuing to deteriorate, with 3.8 million people at risk of falling into the Emergency (IPC Phase 4) classification. The report states that currency depreciation, rising food prices, and the resulting decline in purchasing power are the primary drivers of this increase in government-controlled areas, with the price of a Minimum Food Basket (MBF) in February up 27 percent over the three-year average. In December 2024, over half of the population relied on crisis or emergency livelihood coping mechanisms. The report warns that the situation was likely to worsen over the winter, as cold weather and water shortages threaten agricultural productivity, especially in Sana’a and Dhamar. A Houthi ban on wheat flour imports, which took effect January 8, is likely to hamper access to food by disrupting supply chains and increasing processing costs.

The FAO’s latest Market and Trade Bulletin also reinforces this dire outlook, warning that food insecurity is expected to worsen, with currency devaluation, rising fuel prices, political instability, and the Houthis’ FTO designation exacerbating the crisis. The report projects that food insecurity will affect up to 17.1 million Yemenis by February 2025. The prices of essential foods, livestock, and labor are high and expected to increase further in the coming months. In areas under government control, the prices of staple food items have increased by 6 to 27 percent since last year, mainly driven by the 46 percent depreciation of the rial year-on-year. Increased fuel prices and shortages have further inflated the cost of transportation and food.

In areas under Houthi control, the currency remains stable. Still, petrol and cooking gas imports have dropped by 30 percent since last year, and fuel shortages could threaten wheat production. Ports in Hudaydah, As-Salif, and Ras Issa have been impacted by Israeli airstrikes, leading to reduced capacity and a reliance on manual unloading, which could affect the volume of imports. Food distribution was critically lacking in 2024, leading to 52 percent of households adopting severe food-based coping strategies. Despite Houthi price controls, declining wages have reduced affordability, as 54 percent of residents in Houthi-controlled areas rely on casual labor for income.

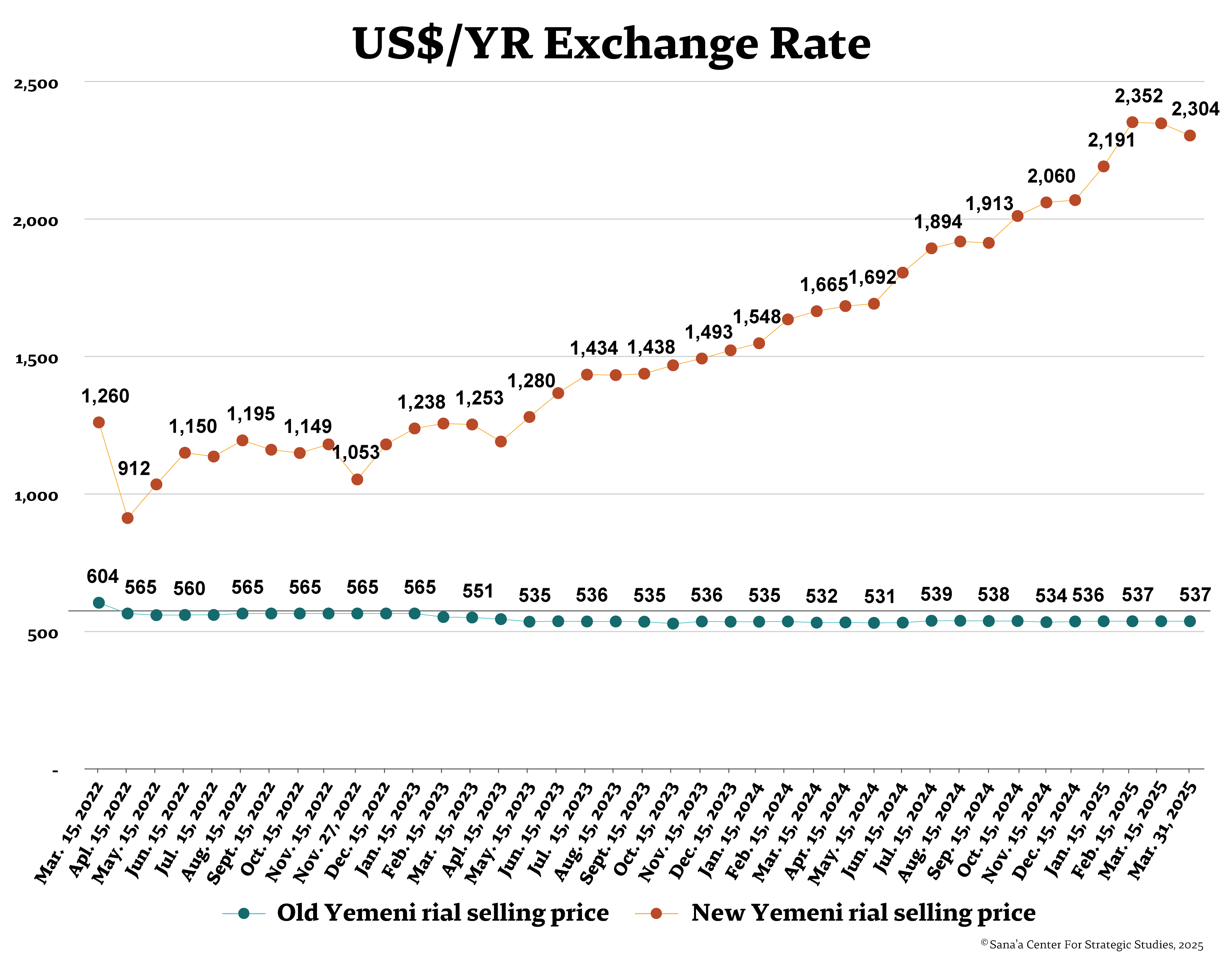

Rial Continues to Depreciate

The new rial has continued its alarming decline in government-controlled areas, hitting a record low of YR2,340 per US$1 by the end of the reporting period. This represents a 15 percent decline relative to the dollar since the beginning of the year and a 52 percent drop since the start of 2024, despite the arrival of new Saudi financial support in late December. Old rials trading in Houthi-controlled areas remained stable, trading at YR537 per US$1.

Several factors have driven devaluation. Deep-seated political divisions within the Yemeni government hinder the effective implementation of a cohesive macroeconomic policy. The lack of unity has created a fertile environment for currency manipulation and speculation by money exchangers and traders operating in an under-regulated market. There was also increased demand for hard currency from commercial traders to finance imports ahead of the holy month of Ramadan, to meet rising demand for food and other commodities.

Saudi Arabia’s latest financial aid payment included US$200 million to help the government continue disbursement of public sector salaries and a US$300 million deposit in the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) to shore up its dwindling reserves. Still, Saudi support, disbursed in four tranches between August 2023 and December 2024, has been inadequate to offset the government’s large fiscal deficit. The government is spending US$70-100 million per month on fuel derivatives alone to operate power stations in areas under its control. The situation is aggravated by the Houthis’ continuing blockade of crude oil exports and the redirection of commercial shipments from government-controlled ports to Houthi-controlled ports on the Red Sea.

The CBY-Aden has repeatedly tried to prop up the rial’s value by auctioning its foreign currency reserves. Between January and March, the CBY-Aden announced eight auctions, each with US$30 million on offer. However, the auctions saw limited participation from Yemeni banks, with subscription rates ranging from 45 to 47 percent. This can probably be attributed to fluctuations in the parallel money exchange markets, which discourage banks and importers from participating. Banks also face further constraints in terms of cash liquidity, most of which is in the hands of money exchangers. In addition, in late March, the CBY-Aden announced two new public debt auctions, hoping to raise YR16 billion through one-year treasury bills with an 18 percent interest rate and YR20 billion through three-year government bonds with an interest rate of up to 20 percent, both with semi-annual interest payments. Despite such fiscal interventions, investor skepticism has limited the CBY-Aden’s capacity to stabilize the rial, and the currency continues to depreciate.

The rial’s declining purchasing power has exacerbated hardship in government-held territory. In January, hundreds of people gathered in Aden to protest the continued deterioration of economic and living conditions and the collapse of the currency. Protesters said they held the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) responsible and warned the government against continuing to ignore their plight. Demonstrators also called on the Saudi-led coalition and the international community to provide further support.

Central Bank Report Highlights Government Deficit

In its Monetary Development Report for December 2024, the CBY-Aden elaborated on the government’s dire fiscal situation. While revenues amounted to YR2,065.6 billion, expenditures amounted to YR2,870.2 billion at the end of December, a deficit of nearly 39 percent. With no real sources of income, the government continues to accrue public debt. The government’s net debt at the bank rose from YR6,628.4 billion in November 2024 to YR7,048.4 362 billion in December 2024, an increase of YR420 billion in the space of a month. Direct borrowing from the CBY-Aden constituted the primary source of financing domestic public debt, amounting to YR6,585.3 billion in December 2024 and accounting for 93.4 percent of total domestic public debt. Domestic public debt instruments (treasury bills, certificates of deposit, and Islamic bonds) constituted the second largest source of domestic public debt, amounting to YR463.2 billion at the end of December 2024 and representing 6.6% of total domestic public debt.

Inflation continued to rise in November despite a 2.6 percent decrease in hard currency in circulation. This upward trend intensified in December 2024, with the monthly inflation rate up by 3.33 percent compared to November. The central bank continues to work with a dwindling budget. Wholly reliant on foreign aid, its ability to stabilize the exchange rate or address other budgetary issues is severely constrained.

Accusations of Corruption Threaten Government’s Standing

There are ongoing reports of corruption and appropriation of state resources in government-held areas. Accusations range from the conversion of public lands into private residences, discounted rentals of government tourism facilities, exploitation of revenue-generating public facilities for personal gains, and the inflated salaries of the PLC members.

A recent media report claims that members of the Southern Transitional Council (STC) close to its president, Aiderous al-Zubaidi, converted a government building in Aden into a private residence. Many other government buildings and lands have been exploited in the same way. Activist Ali al-Nasi claimed that government tourism facilities in Aden are being rented out for small amounts, while they should be generating much higher returns. One of these, the Elephant Resort, reportedly generates YR50 million in monthly revenue while being rented out for a fee of only YR200,000.

A leaked report published on March 12 stated that the members of the PLC receive monthly salaries worth a cumulative total exceeding US$2.981 million. This indicates that the eight council members would have collectively received more than US$104 million between April 2022 and February 2025. Amid the severe economic crisis and persistent corruption scandals, the report is likely to enrage citizens, who have been demanding greater government transparency and accountability.

CBY-Aden Combats Illicit Trading

Facing the devaluation of the new rial and widespread illicit financial activity, the CBY-Aden adopted a litany of strict new regulations targeting money exchange outlets and financial transfer networks. On February 23, the CBY-Aden issued a circular mandating that exchange companies record customer data for all financial transactions and immediately sell all surplus foreign currency to licensed local banks. Exchange companies are now prohibited from acting as agents for local companies, trading foreign currency amongst themselves, maintaining credit or debit accounts for other local exchange companies or remittance agents, or making cash deposits on another’s behalf in any money transfer network. To ensure compliance, the CBY-Aden has said it will conduct surprise field inspections with penalties that may include suspension or cancellation of licenses. The bank also ordered the suspension of buying and selling operations via electronic applications, limiting these to cash transactions. The new oversight measures are intended to combat fraud and currency speculation, which weaken the already unstable currency.

In early March, the CBY-Aden released an official notice warning individuals and merchants against keeping deposits with exchange companies or any other institutions that are not licensed banks. According to existing law, only banks licensed by the CBY-Aden are authorized to open and maintain bank accounts and hold deposits. Moreover, the bank stressed that dealings with unlicensed entities violate provisions of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing (AML/CTF) law and could lead to legal penalties.

Total Blackouts in Aden

The interim capital of Aden has suffered from longstanding blackouts due to government incompetence and mismanagement of the energy sector. Interconnected factors, including fuel shortages, internal disputes, sabotage of infrastructure, and an insufficient budget, forced a complete shutdown of major power stations in the city for over two weeks in late January.

Blackouts paralyzed daily life and disrupted essential services, such as water and sewage systems. Hospitals and health centers were severely affected, while water shortages and the cessation of commercial activity exacerbated the suffering of the population. The situation sparked widespread discontent among citizens already grappling with an infrequent and erratic power supply. Southern governorates, including Aden, Lahj, and Abyan, witnessed angry popular demonstrations, with protesters setting fire to car tires and blocking roads.

The Aden Electricity Corporation explained in a statement that the primary cause of the blackout was the disruption of crude oil supplies to Aden’s main power station, PetroMasila, due to a roadblock on the main highway through Abyan. Fuel shortages also prevented the use of a new 120-megawatt solar power plant, plunging Aden and neighboring areas into complete darkness.

The government faces serious fiscal challenges in sustaining the energy sector, spending an estimated US$1.2 billion a year on fuel and power plant rentals. Government revenues are insufficient to cover these costs, deepening the crisis. The collapse of the local currency has also led to a surge in the price of basic commodities, and fuel has become unaffordable. In Aden, the cost of a 20-liter can of gasoline has risen to YR31,800, up from YR31,300. With prices increasing and salaries either flat or falling, some citizens now pay more than 70 percent of their wages for services such as water and electricity. The blackouts in Aden underscore broader failures of governance and a lack of coordination between local authorities, energy companies, and fuel suppliers. As the situation worsens, the risk of further social unrest grows.

Adding to this crisis, the Hadramawt Tribal Alliance (HTA) announced in early February that it would halt crude oil shipments to Aden in the latest salvo in its ongoing dispute with the PLC. HTA head Amr bin Habrish justified the escalation by pointing to the PLC’s failure to respond to his demands or implement reforms promised in early January, including the absorption of more Hadramis into the armed forces, the allocation of more oil revenues for local development, and greater participation in governance.

The government has made efforts to restructure its obligations. In February, the General Electricity Corporation (GEC) reportedly sent letters terminating its contracts with independent private power producers (IPPs) supplying diesel-generated electricity. While the prime minister approved the decision to cancel the contracts to lessen the burden on the public budget, there are fears that the lack of alternative providers could further jeopardize Aden’s power supply.

The GEC justified the move by citing the inefficiency of diesel-operated power stations due to persistent diesel shortages and exorbitant costs, which weakened the corporation’s capacity to meet its contractual obligations. For months, Aden’s main diesel and fuel oil-powered generating stations – responsible for approximately 85 percent of the city’s electricity needs – have been entirely non-operational due to the government’s failure to meet its financial obligations to contractors. The move also aligns with the government’s stated policy of limiting its reliance on diesel-powered energy. The PetroMasila power station in Aden and solar power initiatives were cited as potential replacements for the lost generating capacity. However, creating a sufficient and sustainable energy supply from these sources will take both time and massive investment.

The PetroMasila station is emblematic of government incompetence and mismanagement. While possessing a nominal capacity of 270 megawatts (MW), the station currently produces a mere 60MW. The rest of its capacity remains offline due to technical problems that the government has been unable to resolve since it began operation. The station could significantly alleviate Aden’s power shortages if it were to operate at full capacity, but the government’s inability to fix the problems casts doubt on its ability to implement a meaningful, long-term program. Solar power has also been touted as a potential solution, but the supply is currently insufficient to bridge the gap created by the contract terminations.

The World Bank’s announcement in early March of US$159 million for a new electricity “roadmap” of fundamental reforms could offer a respite. Energy projects, including solar power stations, have been nominated to receive technical support from the World Bank and other international institutions. One such initiative, the “Shams” solar project, aims to generate 25 MW, with a planned expansion to 98 MW across multiple governorates. However, activists have warned that the plan may lead to further corruption. The energy sector is notorious for financial mismanagement, absorbing a large portion of the state budget and foreign aid.

Smuggling Exacerbates Gas Shortages

Government-controlled regions are experiencing a severe shortage of cooking gas due to widespread smuggling, politically oriented blockades, and the government’s systematic failure to regulate the energy sector. According to media outlet Aden al-Ghad, smugglers have transported liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) from Yemen overseas to sell it at a premium. They reportedly use two main routes: from the port of Nishtun in Al-Mahra to Somalia, and from the Bab al-Mandab coast to Djibouti. On February 21, the Yemen Gas Company denied the allegations, saying the government is working to combat black market activity.

The supply of cooking gas has been complicated by armed groups imposing roadblocks between governorates. On February 22, gunmen opened fire on trucks carrying cooking gas on behalf of the government-owned Yemen Gas Company in Taiz. For weeks, gas shipments were prevented from moving from Block 18 in Marib, operated by the Safer Company, resulting in widespread shortages and rising prices, reaching more than YR15,000 in some areas. The official list price is just YR4,500. Demand for domestic gas has also increased due to the surge in prices for petroleum derivatives in government-controlled areas. Citizens have taken to using gas as an alternative fuel, putting more pressure on filling stations.

On March 3, media sources confirmed that cooking gas shipments had finally arrived at filling stations in Aden after tribal mediation produced an agreement to reopen transport routes for the week of March 1 to 8. While the temporary resumption of supplies provided some relief and lowered prices, more effective regulation and long-term agreements between local actors and the government are still absent.

Contaminated Fuel Cripples Vehicles in Sana’a

Sana’a and other areas under Houthi control have suffered from a fuel crisis due to a shipment of poor-quality oil derivatives. The Houthi-controlled Yemen Petroleum Company has been accused of flooding the market with contaminated fuel, causing engine failures and sudden breakdowns in hundreds of vehicles and motorcycles.

Media outlets reported that the tanker Love, carrying 60,639 tons of substandard Iranian oil, docked at the port of Ras Issa on December 26 of last year. The shipping agent was the Taj Oscar company, which is reportedly linked to corrupt officials within the Yemen Petroleum Company in Sana’a. On February 20, the unloading process began, with the contaminated oil transported directly to the market via tugboat due to the lack of sufficient storage tanks. Within two weeks, drivers reported recurring, crippling malfunctions after refueling at local stations. Notably, no other oil tankers have since unloaded.

Facing mounting public outrage, the Yemen Petroleum Company issued a statement on March 22, acknowledging complaints of vehicle malfunctions but without mention of the tanker or low-quality Iranian fuel. The company said it had assigned field technicians to visit a number of fuel stations to inspect the fuel and study vehicles that had suffered technical failures to determine the causes. It also stated that it had taken measures to enhance oversight until it can diagnose the defect, if any, and implement necessary solutions.

Activists and critics have accused Houthi leaders of orchestrating the scheme to maximize profits, alleging that the Yemen Petroleum Company’s provision of oil to Houthi-controlled firms has opened the floodgates for corruption. The company’s failure to disclose the name of the shipment’s importer, coupled with deafening silence from the authorities, points to a network of Houthi businessmen benefiting from illicit fuel revenue streams.

The fuel crisis has its roots in the Houthis’ 2015 decision to effectively privatize the import of fuel, handing over control to traders affiliated with the group. This policy has not only raised fuel prices but also created a lucrative market for the Houthis to exploit.

Sana’a Authorities Centralize Revenue Collection

On March 5, the Houthis introduced an electronic payment system for customs revenues at the ports of Hudaydah and Al-Salif. The group claims the system will facilitate business, enhance transparency, and save money, but it is also clearly a tool for directly controlling revenue flows.

Since the formation of a new Houthi government last August, the group has aggressively and systematically dismantled or restructured every ministry and public authority under its control. The campaign has targeted key revenue-generating authorities, cementing the group’s grip on Yemen’s financial arteries. Media reports have questioned the effectiveness of some institutional mergers, citing conflicts over appointments and interests.

The Houthi political leadership had announced a new head of the customs authority, but it backtracked when incumbent chief Adel Margham agreed to form a committee to merge the customs and tax authorities. The merger will allow the group to extract higher tax and customs revenues from businesses and traders and to funnel these funds directly to top Houthi leaders and military operations.

The restructuring is likely to result in increased restrictions and barriers to trade and higher fees for importers. As the FTO designation comes into effect, the Houthi economy will be further isolated, resulting in hardship for citizens as businesses face increased taxes and potential legal ramifications.

CBY-Sana’a Begins Destruction of 100-Rial Banknotes

In mid-March, the CBY-Sana’a began destroying YR13 billion of 100-rial banknotes. The bank said the notes were being destroyed because of their physical deterioration. Citizens and institutions have been urged to exchange damaged 100-rial banknotes for coins minted by the group at designated centers.

The CBY-Sana’a announced a new coin to replace deteriorating 100-rial banknotes in March 2024. At the time, the announcement was criticized by the CBY-Aden and the US, EU, and the UK, who viewed it as a deliberate attempt to erode the country’s financial stability, deepen existing monetary divisions, and impede the precarious peace process.

While the UN’s intervention in the economic war between the central banks last summer seemingly put a pause on these plans, the destruction of the 100-rial banknotes again raises questions over the potential impact on liquidity, especially in light of the recent FTO designation. Beyond concerns over inflation, the move threatens the CBY-Aden’s mandate as the sole printer of the national currency.