In mid-2015, Yousef[1] and his extended family escaped from an aerial bombardment near his hometown, Al-Shareefiah, a village outside Haradh in northern Hajjah governorate. The 68-year-old head of a large household had found refuge in Hayran, a nearby district, hoping the airstrikes would stop soon so he and his family could return to their homes and large banana plantation. But air and ground attacks intensified in Haradh and nearby areas, including Hayran, where they were taking shelter. He and his family were soon on the run again.

Now, nearly a decade since he abandoned his hometown, Yousef lives with his family in a makeshift camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs). They have never been able to return home, nor have the other local families who were uprooted from the border town of Haradh, once home to over 100,000 people.

In mid-2018, fighting erupted near Al-Durayhimi in western Hudaydah governorate, driving entire families from their villages. Kareem and his family were among the first to leave. Like many other families, the 48-year-old father of five first took shelter outside Al-Durayhimi before he and his family moved to Hudaydah city. After nearly five years of displacement, the family finally managed to return home in early 2023. Al-Durayhimi used to boast large numbers of date palms, but when Kareem returned, he found his hometown bombed out and infested with land mines.

The displaced populations of Haradh and Al-Durayhimi have faced similar calamities. Situated on the ends of the 420-kilometer Tihama plain, both towns were the epicenters of fighting for years. Local populations were uprooted, and some families still cannot return to their homes and livelihoods, as streets and fields are still littered with unexploded ordnance.

While hundreds of local residents, including Kareem’s family, have managed to return to their homes in Al-Durayhimi, none of Haradh’s displaced population, including Yousef’s extended family, have been able to go back. Both families are beset by harsh conditions, having dealt with inadequate assistance and protection at displacement camps and little or no help to facilitate their safe return to their homes and livelihoods.

Haradh: “A Ghost Town”

On March 26, 2015, a Saudi-led coalition began an aerial bombing campaign in Yemen to roll back the Houthis, who had seized power in the Yemeni capital, Sana’a, and taken control of large swathes of northern Yemen. Haradh town, along with other areas in its district, immediately came under a heavy bombardment that lasted for several months. Fighting for the border town and the nearby port of Midi raged until 2022, pitting pro-government forces backed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates against the Houthis.

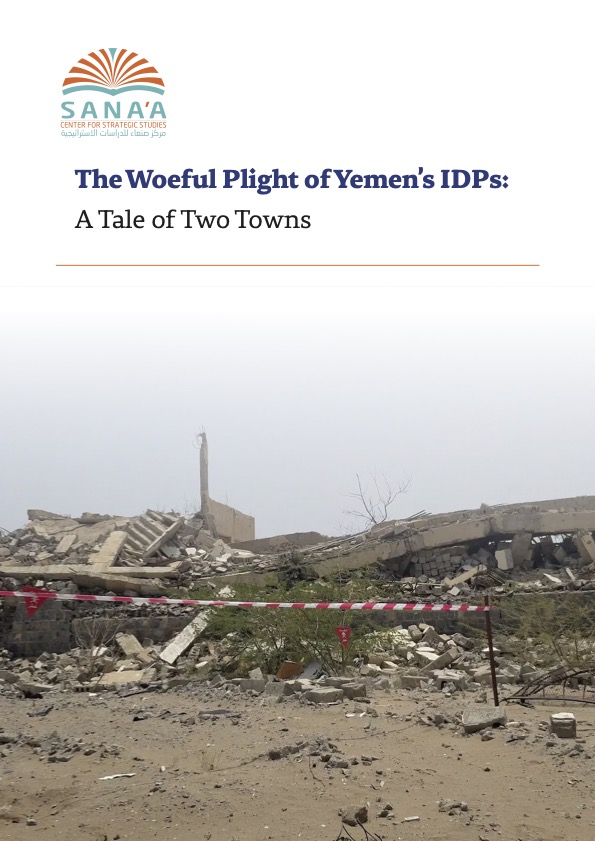

Before 2015, Haradh was so bustling with around-the-clock business activity that it was known as a ‘town that never sleeps.’ Situated just four kilometers from the border with Saudi Arabia, Haradh was home to one of Yemen’s vital border crossings, Al-Tuwal, through which a significant portion of non-extractive exports passed—particularly crops and fish from the coastal Tihama plain. But with civilian houses and public infrastructure razed to the ground, the trade through Al-Tuwal came to an end. Haradh now looks like a ghost town.

“When we first took shelter in [the neighboring district of] Hayran, I thought the airstrikes would last for a week or so; I really hoped we would be able to return to our village that soon,” Yousef said from his shelter at an IDP camp outside Hudaydah city. “But we couldn’t return, as the bombing continued to intensify day after day. Our houses and farms came under air attack, and some workers were killed. Even the areas in which we took shelter saw heavy airstrikes, and we had to run for our safety multiple times.”

On March 30, 2015, an airstrike hit Al-Mazraq camp outside Haradh, which had been sheltering some 12,000 IDPs from Yemen’s Sa’ada wars since 2009. At least 40 people at the camp were killed and about 200 others wounded. Over the next four months, Human Rights Watch (HRW) documented at least seven cluster munition rocket attacks by the Saudi-led coalition in Hajjah governorate. Six of these were in Haradh and killed and wounded dozens of civilians. HRW had also found ”unexploded submunitions scattered” in fields used for farming and grazing, which threaten “the livelihoods of local farmers and add to food insecurity.”

As in other parts of the Tihama plain, arable farmland sits on the outskirts of the town Haradh, where local farmers would cultivate several kinds of fruit. Yousef left behind a large banana plantation in his hometown, Al-Shareefiah, along with several commercial businesses in downtown Haradh. Most of his 15 sons used to help him run the 66-hectare banana farm. Yousef’s three brothers also had to abandon their own farms in Al-Shareefiah, each of which was almost as large as his banana plantation.

Yousef’s farm previously employed dozens of hired hands and his business was running successfully. “Before the [2015] war, I had about 70 fixed workers at my farm, dozens of daily laborers, and 30 water pumping generators were in use at the time for irrigation,” Yousef said, recalling those times with a rueful grin. “I used to distribute large numbers of bananas to several Yemeni markets and to Saudi Arabia overland.”

Yousef said it has been too difficult for him and his family to start over while they are displaced, even though they kept a large sum of money on hand. “We have tried, but we unfortunately failed,” he said. “We have had to spend a lot of money to cover household expenses over the years, and recently, we had to sell some of the cars, which we took with us when we first escaped from the airstrikes.”

According to Yousef, none of the residents of Al-Shareefiah have been able to return to their homes and livelihoods so far. “For only one time, I was recently allowed [by the Houthis] to briefly check on my gas stations and other properties in downtown Haradh,” he said.

Despite a lull in hostilities in Haradh since 2022, when a UN-brokered truce was announced, the district is still split, with one part, which includes the Al-Tuwal border crossing and Al-Shareefiah, under government control and the other under Houthi control.

“I am an old man,” Yousef said. “I don’t see any chance of going back home anytime soon, or even a chance of being buried in my hometown when I am gone. I just hope that my family will be able to return home and start their normal life once again.”

Al-Durayhimi: “A Mine-infested Hometown”

In mid-2018, the Joint Forces on the West Coast, backed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, advanced on the key port of Hudaydah in an offensive aimed at retaking it from the Houthis. Home to some 60,000 people, Al-Durayhimi lies some 23 km south of the port city and was the epicenter of a major battle. Kareem and his family had already escaped earlier in the year as other Houthi-controlled districts in southern Hudaydah, including Al-Tuhaytah, Al-Khowkha, and Hays, witnessed fierce fighting.

“We knew that the government forces were coming toward us, slowly but surely, and we had to escape before we were caught in the crossfire,” Kareem said in Hudaydah city. “It was morning when we left our home, along with a few other families; we took a specific dirt road, which the Houthis said was the only road out that had no landmines.” He first took his family to At-Taif, a fishing village southwest of Al-Durayhimi, before they relocated to Hudaydah city.

In December 2018, the warring parties signed the Stockholm Agreement, which included a cease-fire deal in Hudaydah city and its three seaports, as well as plans to demilitarize the city. But hostilities in southern Hudaydah never actually ceased. Al-Durayhimi remained under blockade for the next three years until the Joint Forces pulled out unexpectedly in late 2021. But Al-Durayhimi, Al-Tuhaytah, Al-Khawkhah, and Hays districts remain littered with landmines. Although demining efforts continue, thousands of mines still hide beneath the soil, making southern Hudaydah one of the most mine-infested areas in Yemen.

The UN Mission to Support the Hudaydah Agreement (UNMHA) reported that 41 people had been killed and 52 others wounded by landmines and explosive remnants of war in the governorate during 2024—40 percent of whom were women and children. The districts of Al-Durayhimi and Al-Tuhaytah in southern Hudaydah recorded the highest number of casualties. In March of this year, UNMHA recorded five landmine incidents in Hudaydah, two of which occurred in Al-Durayhimi. “The increase in both the number of incidents and casualties in March compared to February underscores the escalating threat posed by landmines and explosive remnants of war in Hudaydah,” the UN said.

A Common Future

Farming and fishing have long been important livelihoods for residents of the Tihama. But the threat posed by landmines and unexploded ordnance not only continues to hamper families’ efforts to return home but also their ability to support and sustain themselves.

Last June, a couple was killed when their motorcycle struck a mine outside Al-Durayhimi. On the same day, outside Haradh, a 14-year-old boy stepped on a mine while tending sheep near the Al-Shalilah IDP camp, losing his left leg. In December, a 13-year-old boy was tending sheep in the Bani Hassan area of Abs district, where most of Haradh’s IDPs have found refuge, when an explosive device camouflaged to look like a toy went off. He lost his left hand in the explosion. A week later, four children, aged between 4 and 14, were wounded in two separate mine explosions that took place inside and on the outskirts of Al-Durayhimi town. Three of them belong to one extended family.

As Yemen experiences yet another round of renewed conflict, mines and unexploded ordnance from previous rounds of conflict remain a menace in farmland and pasture and a reminder of the long-lasting impact of war.

This article is part of a series of publications produced by the Sana’a Center and funded by the government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The series explores issues within economic, political, and environmental themes, aiming to inform discussion and policymaking related to Yemen that foster sustainable peace. Any views expressed within should not be construed as representing the Sana’a Center or the Dutch government.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية