De Facto Partition of Yemen Looms with Riyadh Agreement’s Continued Failure

The Riyadh Agreement, signed one year ago, has failed in almost every aspect of its implementation. As its promise to act as a unifying force in Yemen continues to fade into the past, the de facto partition of the country is coming evermore into focus on the horizon.

As the name suggests, the agreement was of Saudi design. Through it, the kingdom had sought to assume ultimate authority over the Yemeni forces confronting the armed Houthi movement – which had seized Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, and much of the country’s north five years earlier – and to mend the oft-violent confrontations among those parties that were undercutting the fight against their common Houthi foe.

The agreement envisioned Saudi Arabia becoming patron to the Southern Transitional Council (STC), taking over from the United Arab Emirates as Abu Dhabi drew down its military involvement in Yemen, and absorbing the STC into the internationally recognized Yemeni government. STC-affiliated fighters had driven the Yemeni government from its interim capital, Aden, in August 2019, and in exchange for relinquishing control of the city and folding their armed forces into the Yemeni government’s military and security bodies, STC figures were to receive cabinet positions, among other political and security posts, and be represented in any future government delegation attending United Nations-backed peace talks to end the wider war.

Implementation of the agreement’s political and military clauses was to begin immediately and be completed within three months – an absurdly ambitious schedule for the sweeping integration of bitter rivals into a unified body. Every implementation deadline was missed. Sporadic Saudi efforts to revive the agreement since, including throughout October, have witnessed much talk and speculation with little outcome.

Various factors have helped stall the agreement’s implementation, including intense animosity among the implementing parties, a lack of technical details regarding implementation, the sluggishness of Saudi decision-making in responding to changing circumstances on the ground, among others. A factor underlying many others, however, is a fundamental disagreement regarding the sequencing of the deal’s political and military aspects: the STC wants its political position secured before relinquishing its military advantage in parts of southern Yemen, while Yemeni President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi wants military and security integration to occur before he surrenders any political authority. The parties have at various times feigned compromise while avoiding concessions that would meaningfully impact their points of leverage against the other.

A similar impasse in 2016 was a primary factor responsible for scuttling UN-backed peace talks between Hadi’s government and the armed Houthi movement as well as a peace initiative then-US Secretary of State John Kerry had pursued. Hadi insisted that the political dimensions of a post-conflict government would not be decided before Houthi forces handed over their heavy weapons and withdrew from areas they had seized, while the Houthis refused to give up their military leverage until their place in a post-conflict government was assured. In the years since, and without a wider political deal, the Houthis’ military clout has allowed them space to entrench themselves and create their own political reality in the territory they control. Today, they are clearly building the contours of a state in their image in northern Yemen, and in so doing, making the path to a reunified country increasingly fraught.

The Riyadh Agreement’s failed implementation has, similarly, created space for the STC to leverage its military control over Aden and surrounding governorates to attempt to create the conditions to fulfill its ambitions for southern Yemen’s secession. These efforts saw the group declare self-rule in southern Yemen in April, following which, and in direct contravention to the Riyadh Agreement, it took meaningful steps toward establishing a financial basis for independence by redirecting state revenues in areas it controls – such as from the Aden port – to its own newly created quasi-state financial institution.

Historic intra-southern animosities and regional identities almost certainly prevent the STC from extending its control in southern Yemen to the governorates east of Aden, and Riyadh was ultimately able to pressure the STC into rolling back assertion of self-rule. Still, the STC remains the de facto authority in south Yemen’s largest city and the nearby governorates of Lahj and Al-Dhalea and, on current trajectories, its continued political entrenchment in these areas seems likely. Meanwhile, the Yemeni government – having been ousted from the country’s capital and its interim capital – is facing increasing pressure from Houthi forces in Marib, its most significant remaining stronghold.

The Yemeni government’s continued retreat from relevance in Yemen in the months and years to come would likely further spur a de facto, patchwork partition of the country, while maintaining a single Yemeni state in legal identity only, a situation similar to Somalia. The Riyadh Agreement, while heavily flawed, likely represents the best, and perhaps even the last, viable option to reverse this course.

Contents

October at a Glance

Developments in Yemen

Prisoner Exchange

Over the course of two days, October 15-16, the Yemeni government and the Houthis exchanged 1,081 prisoners in a deal facilitated by the International Committee of the Red Cross as part of the 2018 Stockholm Agreement. Among those released was Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar’s son, Mohsen Ali Mohsen. (For more see Nadwa al-Dawsari’s commentary ‘Yemen’s Prisoner Exchange Must be Depoliticized’).

Majed Fadhael, deputy minister of human rights for President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s government, said there would be talks on another prisoner exchange before the end of 2020, which would include several high profile figures such as the president’s brother, Nasser Mansour Hadi, Mahmoud al-Subayhi, the former minister of defense, and Mohammed Qahtan, an Islah party politician.[1]

In a related deal, the Houthis released two US citizens, Sandra Loi and Mikael Gidada, as well as the remains of a third American, Bilal Fateen.[2] In exchange, 250 Houthi fighters, who had traveled to Oman to receive medical treatment, were allowed to return to Houthi-controlled territory.

Iranian Ambassador Appears in Sana’a

The Iranian foreign ministry announced on October 17 that Iran’s newly appointed Ambassador to Houthi-controlled Yemen, Hassan Irloo, had arrived in Sana’a.[3] (The Houthis appointed an ambassador, Ibrahim al-Daylami, to Iran in August 2019.) Iran is the first state to establish diplomatic relations with the Houthis.

There has been some speculation that Irloo was smuggled into Yemen on the flight from Oman, which was overseen by the UN Special Envoy’s office. The Office of the Special Envoy for Yemen, however, has officially denied any involvement in his transfer to Sana’a.[4] Yemen has submitted a formal complaint to the United Nations Security Council, calling it a breach of Iran’s international obligations and a dangerous precedent for allowing “rogue regimes” to violate state sovereignty.[5]

State Department spokesperson, Morgan Ortagus, said in a statement on Twitter that Irloo has ties to Lebanese Hezbollah.[6]

Houthi Minister Assassinated in Sana’a

On October 27, Hassan Zaid, the Houthi-appointed minister of sports and youth and the head of the Al-Haqq party, was assassinated when gunmen opened fire on his car in Haddah neighborhood of Sanaa.[7] The assassination came amid heightened security measures throughout the week in Sana’a city in preparation for the Prophet Mohammed’s birthday, which began at sundown on October 28. This is the highest-profile assassination of a Houthi figure since August 2019, when Ibrahim al-Houthi, the brother of Abdelmalek al-Houthi, was killed in Haddah.

Hadi-STC Cabinet Rumors

President Hadi and STC leader Aiderous al-Zubaidi met in Riyadh on October 22, fueling speculation that a new “unity” cabinet will soon be announced in accordance with the Riyadh Agreement. The STC is reportedly slated to receive six of a proposed 24 cabinet slots, half of the 12 alloted to southern Yemen.

The current hold-up is over sequencing. Hadi’s government insists that the cabinet will only be formed after units affiliated with the STC redeploy from positions in Aden and Abyan. The STC wants the cabinet announcement to precede any military redeployments. (For more see Hussam Radman’s ‘The Riyadh Agreement One Year On’.)

Disruption at Aden Port

In early October, retired southern military officers disrupted normal activities at the port in Aden, calling for the payment of their outstanding pensions.[8] Service resumed at Aden Port on October 12, following the intervention of Aden Governor Ahmed Lamlas and the assurances given to the retired military officers that they would receive their pensions soon. The retired military officers remained camped next to the port at the time of publication.[9]

Economic Developments

Easing of the Fuel Crisis

During October, the Yemeni government authorized the entry of seven vessels to Hudaydah Port carrying a combined 140,000 metric tons of fuel.[10] The surge in activity marked an easing of the latest Hudaydah fuel import standoff between the government and the Houthis that began in June 2020 when the government suspended fuel imports to Hudaydah for the entire month. (For more details see: Yemen Economic Bulletin: Another Stage-Managed Fuel Crisis.[11])

Drivers in Sana’a waited long hours in line to refuel after fuel shortages began to take hold in Houthi-held areas this summer, June 15, 2020. // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

The reduction of fuel imports via Hudaydah and subsequent increase in fuel import activity in Aden prompted a rise in insider trading, according to both a government official and a fuel industry researcher in Aden, whereby local fuel traders would purchase fuel from the local market in Aden and then truck the fuel to Houthi-controlled territories where it would then be resold at higher profit margins.[12]

The resumption of fuel import activity at Hudaydah coincided with a drop in fuel prices and decreased lineups at petrol stations in Houthi-held areas in the second half of October. In the first half of October fuel was being sold at around 18,000 Yemeni rials per 20 liters on the black market; by the end of month, limited fuel was once again available at petrol stations at the ‘official price’ of 5,900 Yemeni rials per 20 liters.[13]

Battle of the Central Banks

In mid-October 2020, the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Aden, which is affiliated with Hadi’s government, referred members of the boards of directors of three Yemeni banks to the Public Prosecutor for failing to provide CBY-Aden with data related to their operational banking activities. According to the complaint, Yemen Kuwait Bank, Yemen Reconstruction and Development Bank, and the International Bank of Yemen refused to provide the requested data out of fear of punishment from the central bank in Sana‘a, which is under Houthi control.

At the end of September, the Houthis had sanctioned Al-Kuraimi Bank for adhering to CBY-Aden instructions instead of those issued by CBY-Sana‘a. This resulted in a brief closure of Al-Kuraimi operations in Houthi-controlled territory until the bank paid YR 1 billion in fines.[14]

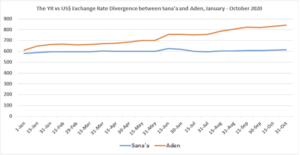

Since the schism of the CBY in 2016, the two central banks in Sana’a and Aden have increasingly competed for monetary authority, financial sector management and control over import financing. A full-blown currency war erupted in January this year when the Houthis banned newly printed banknotes issued in Aden from circulating in Houthi-controlled areas (for details see: Yemen Economic Bulletin: The War for Monetary Control Enters a Dangerous New Phase). The Yemeni rial exchange rate has since increasingly diverged between Houthi- and Yemen government-controlled areas.

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

Death Penalty Ruling in Al-Aghbary Case

Five men arrested for the torture and murder of Abdullah al-Aghbary in late August have been sentenced to death in a recent court ruling, according to the defendants’ lawyer.[15] The murder sparked public outrage when its details went viral last month, resulting in protests and added pressure on Houthi authorities to convict those responsible. Courts under de facto jurisdiction of the Houthis have been described by civil rights organizations as falling short of standards of independence and fair trial, having issued more than 200 death sentences since 2017.[16]

Decrease in Cholera Cases in 2020

A suspected 197,377 cases of cholera have been reported in Yemen so far this year, according to the WHO. Though still significant, the number is a 72 percent decrease in cases from 2019.[17]

International Developments

In the United States

On October 6, the American Civil Liberties Union won a lawsuit against the Trump administration requiring it to disclose its policy on the use of drone strikes in places where the US has not declared war, such as Yemen and Somalia.[18] The ACLU argues that Trump administration rules have loosened Obama-era restrictions aimed at limiting civilian casualties and procedures for selection of targets.[19] On October 26, Airwars published a 38-page report, titled “Eroding Transparency,” on the Trump administration’s counterterrorism actions in Yemen.[20]

Twitter Suspends Houthi Account

On October 8, Twitter suspended accounts linked to the Houthi’s al-Masirah news channel.[21]

State of the War

By Abubakr Al-Shamahi

Marib

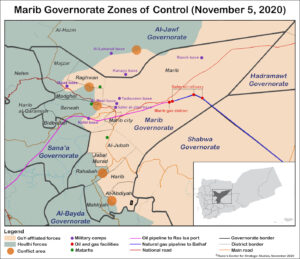

The Houthi offensive in Marib stalled in October, as Yemeni government forces rallied and mounted an effective defense following weeks of Houthi advances. In particular, the Houthis have been looking to take control of Al-Jubah and Jabal Murad, two districts in southern Marib, after seizing the neighboring district of Rahabah in early September. However both districts, and Jabal Murad in particular, are the heartland of the powerful pro-Yemeni government Murad tribe, and Murad military figures redeployed from other frontlines to support Yemeni government and allied tribal forces. Clashes between the two sides on this frontline were a common occurrence in the first half of October, but dwindled in the second half of the month.

In early October, Houthi forces began work on a dirt road to the Ablah area in the Yemeni government-controlled Al-Abdiyah district, in an attempt to reach the area, according to local tribal sources. However, they stopped work later in the month. The Houthis have found it particularly difficult to advance in Al-Abdiyah, but control of Ablah would enable them to cut supply lines from Marib city to the pro-government Bani Abd tribe in Al-Abdiyah.

The Houthi offensive in Marib also stalled in Medghal district, in the northwest of the governorate, where Yemeni government forces remain in control of roughly a third of the district. The Houthis are now on the defensive in this area, seeking to hold on to areas they took in the past few months. Houthi control over much of the high ground in and around Medghal limits possible government counterattacks.

Al-Jawf

In Al-Jawf, Yemeni government forces had some successes in early October, most notably taking the Al-Khanjar base in Khabb wa Al-Sha’af district, in the southwest of the governorate. Yemeni government forces have sought to secure the area around the base, as well as conduct an offensive toward Bir al-Maraziq in Al-Hazm district, as they attempt to get closer to the governorate capital of Al-Hazm. On October 10, General Abdulaziz Hankal, the commander of the Yemeni government’s 110th Infantry Brigade, was killed in action.

Hudaydah

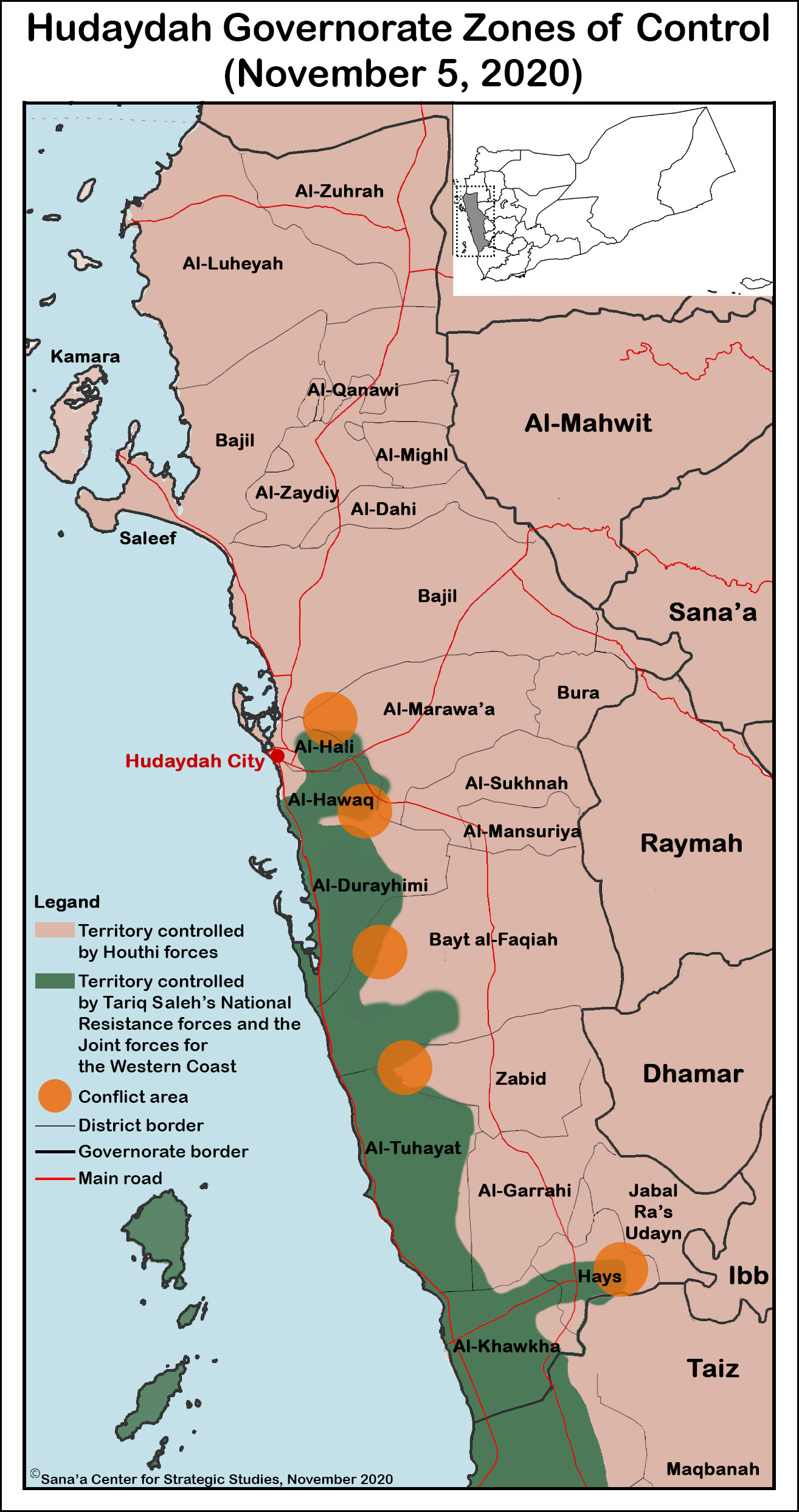

With their advances temporarily paused in the north of the country, the Houthis shifted their focus to other areas. On the Red Sea Coast, Hudaydah saw its most intense fighting of the year, particularly in and around the city of Al-Durayhimi, south of Hudaydah city. A Houthi offensive in early October sought to link up with Houthi fighters who had been inside the city since May 2018, but had been surrounded by Saudi-led coalition-backed Joint Forces. On October 5, the Houthis were able to break through Joint Forces lines in the northwest of Al-Durayhimi, and then attempted to break through from the east of the city as well. However, by October 9, the arrival of reinforcements for the Joint Forces led to a counterattack against the Houthis, and the Joint Forces currently surround the Houthis from three sides of the city: the north, east, and west. The fighting led to dozens of casualties, including civilian deaths. Heavy fighting also occurred in Hays city, in the southern part of the governorate, and in the outskirts of Hudaydah city itself.

Al-Dhalea

The Houthis also intensified their attacks on the joint Yemeni government and Southern Transitional Council (STC) forces in Al-Dhalea in southern Yemen. This may be linked to the slowdown of Houthi advances in Marib, and part of an attempt to take advantage of the continuing dispute between the Yemeni government and the STC. The heaviest fighting in Al-Dhalea was seen in Qa’atabah and Al-Dhalea districts, in the governorate’s northwest and west, respectively.

Taiz

In Taiz city, where frontlines have been largely static for the past two years, an offensive by Yemeni government forces in mid-October led to the capture of the Lawzam citadel, on the eastern outskirts of the city. The advance marked a significant victory for Yemeni government forces, but it was quickly reversed. On October 14 Yemeni government forces were forced to withdraw from the area after coming under heavy Houthi bombardment.

On the same day that Houthi forces pushed government forces out of Lawzam, the group also launched intensified rocket attacks on several Yemeni-government-held residential neighborhoods of Taiz city – Al-Ashbad, Al-Jahmaliya, Al-Shammassi, and Wadi Sala. Doctors Without Borders (MSF) said they had treated 38 people injured as a result of the clashes, and that one person had died.

Abyan

Clashes continued between Yemeni government and STC forces in Abyan, where the July deal for both parties to return to the Riyadh Agreement, and the deployment of coalition observers, have not succeeded in halting hostilities. Fighting remained centered on the Shaqrah frontline, east of Zinjibar. Clashes also took place in the Ahwar district, leading to the death of one Yemeni government soldier.

Abubakr Al-Shamahi is research liaison at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. As a journalist his work has appeared in outlets such as Al-Jazeera English, The Guardian, TRT World, the New Arab, and the BBC. He tweets at @abubakrabdullah.

Feature

What Happens When COVID-19 Hits the World’s Worst Humanitarian Crisis?

Bombed and battered by nearly six years of war, Yemen’s hospitals were struggling long before the country’s first confirmed COVID-19 case in April. The country doesn’t have enough doctors, ICU beds, ventilators, or testing to get a handle on the scope of the problem, case count, or casualties. Shuaib Almosawa reports on the current situation in Sana’a.

*Editor’s Note: For security reasons, medical staff and patients who discussed the situation in Sana’a hospitals are identified only with pseudonyms.

Plastic sheeting limits contact between staff and customers at a pharmacy in the Qa’a Al-Ulufi area of Sana’a on May 21, 2020. // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

The patients in the ICU greeted each other with a nod of the head, lying in bed and hooked to ventilators. “I saw patients dying one after another and being put in plastic bags,” Faisal said, recalling the moments before he went into a coma back in May at Kuwait Hospital, the main facility for treating COVID-19 patients in the Yemeni capital, Sana’a. Faisal said his case seemed so hopeless that the nursing staff threw him a party upon recovery. When his family would ask about his health, the hospital staff would reply with “pray for him.” “Some [relatives] had even rushed to dig my grave,” he said.

When Yemen’s first COVID-19 case was confirmed in April, many expected the disease to decimate the already hurting country. In June, Lise Grande, the UN’s humanitarian coordinator in Yemen, told CNN that she expected “the death toll from the virus could exceed the combined toll of war, disease and hunger over the last five years.”[22] Although the current case numbers and fatalities are unknown – and Yemen’s official numbers, as of publication, are 2,064 cases and 601 deaths are undoubtedly only a fraction of the real number – the virus appears to have receded in Sana’a. After a brief shutdown this summer, the city has largely returned to life and few people are wearing masks or socially distancing. Whether COVID-19 has largely run its course in Yemen, or whether this is a lull before another spike in cases, is unclear.

What is clear, at least so far, is that COVID-19 has not been the knockout blow many feared. Instead, the virus has become just one more challenge – to go along with cholera, food shortages, a lack of potable water, a cratering economy, and bombings – in a war in which most of the dead are uncounted. In Aden, a new though not yet peer-reviewed study using satellite imagery suggests that death rates in the southern port city may have doubled over the summer as a result of COVID-19.[23]

The World Health Organization has noted the sharp decline in the reported COVID-19 cases, but has blamed it on difficulty in accessing health care, underreporting by the health officials, and fear of seeking treatment, among other reasons.

As the outbreak began in mid-March, the first thing one Sana’a doctor did was write out his will and send his children to his home village. In the beginning, everyone was panicking, Dr. Ibrahim recalled, including the medical staff. “No doctor agreed to work; they all ran away,” he said, adding that some returned after assurances that no one would work without the required personal protection equipment.

Dr. Ibrahim said he had expected the death toll due to COVID-19 to reach 200,000 in the capital alone, where about 6 million people live. Instead, he estimates fatalities have been in the hundreds. The Houthi-controlled Ministry of Health in Sana’a has refused to disclose true numbers of cases or deaths. Officially, the Houthis have confirmed only four cases and one death.[24]

Anecdotally, Sana’a’s COVID-19 peak appeared to have hit between mid-May and July, when the 16-bed ICU at Kuwait Hospital was filled to capacity. During that period, patients arriving in need of an ICU bed would be turned away, recalled a second doctor, who was a member of the hospital’s medical staff. “We would tell incoming patients that there was nothing we could do beyond the ER,” Dr. Hanan said.

During a typical day, Dr. Hanan explained, about 20 people suspected of having the illness arrived, almost half of whom would die. By the end of June, she said, there was a “remarkable decline” and patients started seeking treatment earlier. Initially, many patients in and around Sana’a did not seek medical help early as rumors of a so-called “mercy injection” – which claimed patients testing positive for COVID-19 would be euthanized – made the rounds on social media.

In Taiz, Yemen’s second-largest city, nurses and officials noted a significant decline in the number of suspected COVID-19 cases around the same time. One of two isolation centers in the city reported only five suspected COVID-19 cases were admitted during the first week of October, but all tested negative. Dr. Muneer al-Humaidi, a member of the Epidemiological Surveillance Committee, which was established by the internationally recognized government’s health office in Taiz to track COVID-19, said that although June and July saw the largest number of deaths, confirmed cases were reported through September. The outbreak came and disappeared out of the blue, he said. “And regardless of the scientific reasoning behind it, we can safely say that we have managed to go past the risk stage we used to have, at least for now.”

While it’s too early to say the outbreak is over, the panic over COVID-19 appears to have largely vanished in much of Sana’a and Taiz. On October 29, thousands of people in Sana’a celebrated the Prophet Mohammed’s birthday by marching through the streets. Restaurants, indoor halls, and schools which were closed earlier this summer have re-opened.

Officials at the health ministry in Sana’a continue to defend their nondisclosure policy. When asked about the apparent decline in cases, Khaled al-Moayad, director of the Epidemiological Surveillance Department, which is responsible for tracking infectious diseases, said: “Heaven knows, seriously.”

Al-Moayad said that initially he and others raised concerns over this secrecy policy with the Houthi-appointed minister of health. Now, however, Al-Moayad argues that keeping the public updated on the death toll would have provoked unnecessary fear. “Take this news bulletin, for example, ‘death toll rose from 20,000 to 50,000!’” he said, pointing to the interactive data of the global tally published and broadcast by the mainstream media. “People would definitely lose their minds.”

The Houthis’ decision to not release public data on cases and deaths may also have been rooted in financial concerns over the impact of shutting down an already anemic economy that has been all but destroyed by the last five years of war. Add in the fact that, regardless of the numbers, the Houthis were not in a position to implement effective mitigation strategies and the “secrecy policy” appeared as the course of least resistance, while also shielding the Houthis from potential public outcry over their handling of the virus response.

Al-Moayad believes that the majority of Yemenis sickened by COVID-19 didn’t seek treatment, but he also believes that cases “have, indeed, significantly dropped to the point where you could say there are hardly any new cases.” A hospital administrator in Sana’a agrees: “While you can’t say that the outbreak is over, there’s been a decline in new cases.”

How people will respond if, as elsewhere, COVID-19 surges again this winter, is unclear. Over the past six years, Yemen has been destroyed by war and a cascading series of crises that seem to multiply and mutate; COVID-19 is merely the latest and takes its place alongside other daily struggles to survive. Few can afford to socially distance or quarantine. One of Sana’a’s army of day laborers, Abu Haidar, who works as a blueberry vendor, explained it this way: “Hunger is the most serious virus.”

Shuaib Almosawa is a freelance Yemeni journalist based in Sana’a. He tweets at @shuaibalmosawa

Commentaries

Prisoners held by Yemeni government forces prepare to board a plane in Aden that will transport them to Sana’a as part of a prisoner exchange agreement facilitated by the UN and ICRC between the government and the armed Houthi movement, October 15, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Ahmed Mohammed Obeid Al-Shutiri.

Yemen’s Prisoner Exchange Must be Depoliticized

By Nadwa Al-Dawsari

In mid-October, the Yemeni government and the Houthis swapped 1,081 prisoners as part of the December 2018 Stockholm Agreement. The prisoner exchange sparked hopes, mainly among foreign observers, that this could be a first step toward peace in Yemen. UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths called it a “very important milestone” while the UN Secretary General called upon all parties to engage with his envoy to agree on a “Joint Declaration encompassing a nationwide cease-fire, economic and humanitarian measures, and the resumption of a comprehensive, inclusive political process to end the war.”[25]

While the prisoner exchange is a positive development, it should not be interpreted as a sign that either the Houthis or Hadi’s government are interested in ending the war. Nor should it be hailed as a “breakthrough” that can improve Yemen’s chances at peace.

There is a reason it took nearly two years to complete this exchange. One of the Stockholm Agreement’s many flaws is that it linked the prisoner exchange issue to broader peace negotiations. This politicized the prisoner exchange process and jeopardized local mediation efforts that had already proven effective.

Since the beginning of the Saudi-led military coalition’s involvement in the war in 2015, thousands of prisoners have been exchanged as a result of local mediation conducted by tribal leaders, community leaders, lawyers, military leaders, ordinary tribesmen and even local NGOs.

For example, in 2015, tribal mediation led by Sheikh Yasser al-Haddi al-Yafi’i led to the exchange of 605 prisoners between the Houthis and Southern Resistance forces.[26] Since late 2017, the Mothers of Abductees Association, a women-led Yemeni NGO, successfully facilitated mediations that led to the release of more than 650 civilians who were forcibly disappeared by parties to the conflict. In Taiz, local mediators have managed to secure the release of over 1,200 prisoners.[27] Hadi Jumaan, a tribesman from Al-Jawf, secured the release of the remains of 1,000 dead fighters and mediated the release of 226 prisoners between the two main parties in February 2019.[28]

“The job of prisoner exchange is a humanitarian one. The UN envoy’s work is focused on political and military matters. Linking the prisoner exchange to the envoy’s negotiations made prisoner exchange subject to negotiations on political and military issues,” Rajeh Balleim, a local tribal mediator in Marib, told me.

Balleim has negotiated the release of more than 350 prisoners since 2016 and he explained that local mediators can work freely and effectively because they are independent and apolitical. Each mediator relies on their social connections and relationships, local influence, and customary rules to reach deals.[29] That element is lacking in the UN-backed high-level negotiations. “Local mediators are not paid by anyone and the parties cooperate with them. Yemenis are brothers. Sometimes you exchange a man on one side for his cousin with the other side. It works because it is that personal,” he added.[30]

The “all prisoners for all prisoners” rule outlined in the Stockholm Agreement was both highly ambitious and highly impractical. The implementation mechanism stipulated that both parties present lists of names and information for all of the 16,000 prisoners, detainees, missing persons, arbitrarily detained, and forcibly disappeared persons within one week, and for the exchange of all the prisoners to take place within 40 days of signing the agreement.[31] This proved extremely challenging, not only from a technical perspective, but also in terms of parties’ willingness to follow through on their commitment to implement the swap.

Negotiations frequently stalled over individual names with, for example, one party wanting a name included on the list but the other party denying that person existed. This became an excuse for parties to refuse releasing any prisoners.[32] “This ‘all-for-all’ rule obstructed many of the exchanges that used to happen locally and at the frontline level,” said Abdurabuh al-Shaif, a tribal leader from Al-Jawf.[33]

Sheikh Naji Murait, a tribal leader in Al-Hayma district, Sana’a governorate, shares this frustration. Murait has led negotiations that resulted in the release of more than 2,500 prisoners since the beginning of the war, and said that his and other mediators’ efforts came to a screeching halt as a result of the Stockholm Agreement.[34]

The chairwoman of the Mothers of Abductees Association, Amatassalam al-Haj, criticized the Stockholm Agreement for lumping in fighters with civilian abductees, which she said undermined the work of her advocacy body. “After Stockholm, all local mediation efforts that the Mothers of Abductees coordinated were rejected by the Houthis,” she said. “They said that the names [we submitted to them] are now part of the prisoner exchange process under the Stockholm Agreement and insisted on keeping the civilian captives. A humanitarian issue turned into a political issue and a bargaining chip.”

According to Al-Haj, the Mothers of Abductees Association has documented more than 3,000 civilians, including journalists and human rights activists, abducted by the Houthi movement, the Yemeni government, and the Security Belt forces in the south. The UN Panel of Experts report for 2017 described this as hostage taking, which is prohibited under international humanitarian law.[35]

Indeed, the drawn-out negotiations over the prisoner exchange may have actually served to incentivize the abduction of civilians in order to exchange them for fighters. According to several sources, including Majed Fadhael, the Yemeni government member in the committee that negotiated the release of prisoners, nearly two thirds of those released by the Houthis were civilians, including five journalists. Houthi forces snatched civilians from homes and checkpoints based on their identity and geographic background. These civilians were then swapped for Houthi fighters.[36]

Al-Haj also warned against including women captives in any prisoner exchange effort led by the UN, saying that “it would legitimize taking women as hostages, prolong their abduction, and make their freedom subject to political and military bargaining.”[37]

The prisoner exchange process must be depoliticized. It should remain a strictly humanitarian issue and should be delinked from the UN-led negotiations.

The UN Envoy should absolutely call for the release of civilian captives and pressure parties to release them unconditionally. He should then remove the prisoner exchange file from the humanitarian measures proposed in the Joint Declaration as well as from cease-fire negotiations so that the fates of these individuals are not at the mercy of progress in peace talks. While the facilitation of the prisoner exchange by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is appreciated, no international organization should monopolize this process. If the ICRC continues to be involved on a purely humanitarian basis and away from the political negotiations, it should consult with local mediators to ensure no harm.

Nadwa Al-Dawsari is a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute. She is a Yemeni researcher and conflict practitioner with twenty years of field experience in Yemen. She tweets at @ndawsari.

A tank from the Islah-affiliated 17th infantry brigade deployed in Taiz as clashes with Houthi forces were ongoing in August 2018 // Sana’a Center photo by Ahmed Basha

Yemenis Must Face the Truth About Our War of Identities

By Abdulghani Al-Iryani

The war in Yemen, while still described as a political conflict between political factions, from the start had an underlying clash between two key identities: northern Zaidi tribes of the high plateau, historically referred to as Upper Yemen, who have dominated most of Yemen for centuries; and the Shafi’i farming communities from what was described as Lower Yemen, which served as the tax base of Zaidi rule. The time for well-meaning denials of the nature of the Yemen war as a conflict of identities has passed and we Yemenis have to face the facts to be able to deal with them.

The armed Houthi movement, Ansar Allah, despite its modern structure, ideology and regional Shia dimension, is nothing more than the most recent iteration of Northern-Tribal-Zaidi (NTZ) power. The lightning speed of its takeover of Sana’a and, indeed, of most of Yemen, was a clear indication that it was a natural heir to its predecessor, the old NTZ elites led by former president Ali Abdullah Saleh. When the Houthis pushed beyond the safe space of the north, into Marib and southern Yemen, they were quickly repelled. The traditional NTZ elites’ complicity with Houthis reveals that they thought, much in the same way as President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi did — that they could use Houthis to weaken their opponents, then absorb the group into the much larger Sana’a-based faction of that elite. By choosing to support the Houthi takeover, these elites revealed their inability to coexist with the rest of the people of Yemen on an equal basis. In a sense, they were saying to others: “Either we rule, or we destroy the unity of this country.”

In so many ways, the Islah party is the flip side of the Houthi movement. This may be a surprising statement, given the Houthis’ impressive military prowess and battlefield successes and the dismal performance of forces generally considered as part of the military arm of Islah. However, Islah is the most expressive political representation of the other large Yemeni demographic, the Shafi’i farmers of Middle Yemen, although the group’s stand against the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) in 1994 weakened its representativeness of the governorates of Aden, Lahj and Al-Dhalea.[38]

The Houthi movement openly expresses the sectarian nature of their political system. Slogans of welayah[39] and other Zaidi doctrines are splashed all over public buildings and in the streets of majority-Shafi’i cities such as Hudaydah. They couldn’t say any more clearly that they view the Shafi’i population as their subjects. In this climate of sectarian polarization, Islah became the main adversary of the Houthi movement.

Islah is also in the crosshairs of a dangerous regional power, the United Arab Emirates. The core of Islah is the Yemeni chapter of the Muslim Brotherhood, which the UAE has classified as a terrorist organization and sworn to eradicate. In Yemen, Abu Dhabi has sought to empower Salafists, particularly in the south, Taiz and along the Red Sea Coast, to counter Islah. While this effort has made some inroads, Islah’s solid organization has helped it stay relevant, and in some cases, such as in Taiz, push back against such groups.

Still, the UAE’s position is only the tip of the iceberg of regional and global antagonism against Islamist parties, and thus, the dilemma for Islah is that it is in a lose-lose situation. Whether the Houthis or the internationally recognized government, supported by the Saudi-led Coalition, win the war, Islah’s very survival is at risk. To exit that doomed situation, it cannot just react. It needs to be proactive.

As Houthi forces close in on Marib, the main stronghold of Islah, the trajectory of the war is becoming clear. The Houthis will make new facts on the ground, disposing of the axiom that has dominated the thinking of many Yemeni and international observers: that peace will be one of “no-victor, no vanquished”. The Houthis will dictate the terms of the coming peace. Naturally, they will opt for the model tried and tested by their forefathers: a settlement between the ruling NTZ elites and their Shafi’i subjects.

The obvious representative of the Shafi’i subjects is a subdued Islah party. Negotiations are ongoing between Islah and the Houthis. The release of the Islah-affiliated Minister of Education Abdulrazzaq al-Ashwal by the Houthis in 2018 was the sign of the first attempt at such negotiations. More recently, Islah MP Fuad Dahaba returned in August to Sana’a to join several other Islah MPs who never left. In all likelihood, the two sides are no longer negotiating the principle of striking a deal; they are probably discussing the terms.

Islah knows full well that time is not on its side. The deal it can get today will not be on the table tomorrow. It is also probably concerned by the mystifying prisoner exchange of the son of General Ali Mohsen, a high value prisoner, for the Zaidi religious cleric and vocal critic of the Houthis, Yahya Al-Dailami. Islah would be foolish to stand by while others snatch deals with the Houthis. Therefore, it is likely to make a deal with the Houthis. Unfortunately, that is likely to be on terms not much different from the deals their forefathers struck with past Zaidi imams.

While such a deal will facilitate an end to the war, the political system that will come out of it will inevitably be a theocratic state that will frustrate socio-economic development and democratization for a generation.

Grim as the situation appears to be, there is still one possible way out. The lines of confrontation could still be rearranged to lead to a more inclusive, participatory and progressive settlement. In 1991, Islah was formed out of a number of core General People’s Congress (GPC) leaders. Though wounded and divided, the GPC remains the party with the largest popular base in Yemen, including a sizable portion of the country’s technocratic elites. Despite its sorry state, the international community, the Gulf Cooperation Council Initiative, the UN Security Council resolutions and common sense dictate that the GPC must play a leading role in any settlement. Notwithstanding its corrupt past, the GPC’s history of moderation is a reassurance to the region and to the world that Yemen can cease to be a regional security concern.

Islah has the choice: Either make a deal with the Houthis and hope they do not double-cross it in the future, or go back to its roots and merge with the GPC, where it can hibernate and wait out this formidable wave of antagonism. A merger of Islah with the GPC would hopefully provide enough assurance to the UAE that Islah would not act against its interests, and so the Emiratis would let it be. The GPC is a loosely organized bureaucratic party,[40] and many of its leaders were previously in Islah or the YSP, or are former Baathists or Nasserites. Islah leaders will not be alone.

This option is one possible way to end the war and give Yemenis a chance for an inclusive political settlement upon which to build a civil state.

Abdulghani Al-Iryani is a senior researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies where he focuses on the peace process, conflict analysis and transformations of the Yemeni state. He tweets at @abdulghani1959.

Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al-Nahyan, Yemeni President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman arrive for the signing of the Riyadh Agreement on November 5, 2019. // Photo credit: SPA.

The Riyadh Agreement One Year On

By Hussam Radman

One year ago, on November 5, 2019, the internationally recognized government of Yemen and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) signed the Riyadh Agreement.

The agreement was intended to do two things at once. First, and most immediately, it was designed to halt the military confrontation between President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s forces and STC-aligned troops, which had reignited in August 2019, allowing the STC to take control of Aden as well as parts of Shabwa and Abyan. Second, the Riyadh Agreement was supposed to smooth over differences between Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and their two allies on the ground.

In brokering the deal, Saudi Arabia hoped to end the near-constant conflict within the anti-Houthi alliance, re-establish a strategic relationship with the UAE in southern Yemen, integrate STC forces into a unified Yemeni military, and further the prospect of a federal state in Yemen.

Both local parties — Hadi and the STC — as well as the international community welcomed the Riyadh Agreement when it was signed last November. The agreement focused on three things: forming a national partnership cabinet, changing local authorities and security chiefs in all southern governorates to improve the livelihood situation in liberated governorates, and restructuring military and security forces in the south as a way of bringing all units under the umbrella of either the Ministry of Defense or the Ministry of the Interior.

One year on, none of these steps has been achieved. President Hadi has taken a few small steps, such as appointing Ahmed Lamlas, the STC secretary general, as governor of Aden. But Aden’s new security chief, Ahmed al-Hamidi, has not yet been able to assume his position. Hadi’s government and the STC have also agreed, in principle, to divide ministerial posts, but only a few of these have been named.

In attempting to midwife the process, Saudi Arabia has been faced with the predictable problem of which issue to deal with first: security or politics. The STC insists that a cabinet has to precede any redeployment of forces, while Hadi’s government is equally adamant that the STC must withdraw its forces from Aden and other flashpoint areas before a cabinet is formed. Neither trusts the other — or Saudi Arabia — enough to take the first step, and Saudi appeals that withdrawal and cabinet formation take place in concert have so far fallen on deaf ears.

In mid-2020, after months of tension, the STC and Hadi did sign a “mechanism to expedite the implementation of the Riyadh Agreement.” The mechanism laid out a three phase approach. First, end the clashes in Abyan. Second, move Hadi’s forces into Aden, withdraw STC forces from Aden, and redeploy them in Lahj and al-Dhalea. Third, declare the new cabinet, which will integrate STC forces into the defense and interior ministries. But much like the Riyadh Agreement itself, the “mechanism to expedite” has not achieved its aims.

There are three reasons for this. First, neither Hadi’s government nor the STC has been willing to commit to a timeframe. Both sides distrust the other. Second, the formation of a new “unity” cabinet may solve little. Decision making will continue to be monopolized by Hadi, Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, and their inner circle regardless of how many STC officials gain seats. Third, the redeployment of STC forces does not mean that these forces will hand over their weapons or renounce their goal of complete secession. Particularly as STC leaders have consistently stated that they view the Riyadh Agreement as an interim step and not a final deal.

Still, Saudi Arabia retains the power and influence, through its economic and military power on the ground, to at least push the two sides to implement a token deal.

Over the past year, Saudi Arabia succeeded in overcoming a number of political obstacles. It pressured the STC to walk back its declaration of self-rule and convinced Hadi to halt military operations in Abyan in June. Saudi Arabia has demonstrated its influence and power at the regional level, but that has yet to translate into success on the ground, where the kingdom is using a carrot-and-stick approach to keeping its allies in line. Reconstruction projections and infrastructure funds are being held out as an enticement, while Saudi Arabia has said that it would use coalition aircraft to deter future clashes.

One year ago, the Riyadh Agreement represented the best of a series of bad options. In a very narrow sense, it succeeded in halting the military confrontation that began in August 2019. But Saudi Arabia has not been able to transform that cease-fire into lasting peace between Hadi and the STC.

Hussam Radman is a journalist and Sana’a Center research fellow who focuses on southern Yemeni politics and militant Islamist groups. He tweets at @hu_rdman.

The Conversation

Q&A with Anna Karin Eneström, Swedish Ambassador to the UN

Anna Karin Eneström currently serves as the Permanent Representative of Sweden to the United Nations. // Photo credit: Agaton Ström

Among the international community, Sweden has played an outsized role related to humanitarian relief, the peace process and gender issues in Yemen. Sweden has previously co-hosted the annual High-Level Pledging Event for the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen. On the diplomatic front, Sweden hosted the Yemeni parties that negotiated the 2018 Stockholm Agreement, and regularly raised humanitarian and gender related concerns in Yemen during its 2017-18 tenure on the United Nations Security Council. Since December 2019, Ambassador Anna Karin Eneström has been the Permanent Representative of Sweden to the United Nations. On October 12, she spoke with the Sana’a Center’s Gregory Johnsen and Waleed Alhariri about, among other things, the importance of involving women in Yemen’s peace talks and why now is not the time to change the UN’s strategy.

*Note: This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Sana’a Center (SC): Your Excellency, prior to your appointment as Sweden’s ambassador to the UN, you served as Sweden’s ambassador to Pakistan and Afghanistan. Do you see any similarities between the conflict in Afghanistan and what is taking place in Yemen?

Ambassador Eneström: I think that there are a couple of similarities. Both countries have had conflicts for a long time—for decades actually—where you have seen both the disagreement and conflict between national parties or actors and international involvement. Both countries are very poor, among the poorest in the region, but also when you look at the world, they are among the poorest countries in the world. I think also when we look at peace processes, the national actors in both countries need to compromise and make concessions, but are deeply split of course, so this would take a lot of effort from both sides. The humanitarian situation in Yemen is much worse now than in Afghanistan, but you have a lot of human suffering because of the conflict in both countries. Then I think also the regional context is very important in both situations. You have the conflict in both Afghanistan and in Yemen impacting the regional stability. You also need the regional actors to take specific responsibility for the peaceful developments in both countries. I think one aspect that I thought a lot about when I was in Afghanistan is the importance of regional integration. I mean, we are not there yet, but this is something for the future to look into; regional integration in both these areas is not only important for stability but also important for the potential economic development. The last thing I would say is the involvement of women in both conflicts. Sweden has, when it comes to Afghanistan and Yemen, pushed for more involvement of women (in the peace process).

SC: Just to follow up on that, taking in mind what you just said about regional integration, are there any lessons you feel you learned in Afghanistan or Pakistan that would be applicable or useful in the Yemen context?

Ambassador Eneström: I think there might be a long way to go for true regional integration in Afghanistan and the region. But I come from one of the most integrated regions in the world, the European Union, and we have seen how important it is to start with economic integration, and that will then lead to further political integration as well. I think there is great potential for economic integration in the area.

SC: This summer, Sweden’s foreign minister, along with the foreign ministers of Germany and the UK, wrote that “Yemen is on the brink of collapse.” Analysts, scholars and diplomats have been saying this for more than a decade. What makes the current moment so acute?

Ambassador Eneström: I think we see as the conflict goes on that it is getting more complex. It’s getting more fragmented. It’s more difficult to get Yemen on the right track. We are seeing the institutions being weakened. But I think there were some positive signs when it comes to dialogue and de-escalation. We saw some stabilization in the south with the Riyadh Agreement. Unfortunately, we see that this is backtracking now. That’s one of the reasons why we see it as acute right now from the political point of view. We also saw that the UN Secretary General called for a humanitarian cease-fire in Yemen, as in other conflicts, and we have not really seen any results from that. So, that is on the political side, and on the humanitarian side, it’s looking really bad right now. It’s not only the humanitarian situation on the ground, but also the fact that the humanitarian appeal is funded I think around 40 percent and this is really worrying. I come from a huge humanitarian donor. We are trying to do everything we can to get more funds into the humanitarian situation. As you know much better than I do, the humanitarian actors have already been forced to close or severely restrict their activities on the ground. They have warned for a long time that the country might go into famine. Then of course you have COVID-19 that will, on top of all this, worsen the situation even more. So this is why leaders in my country and others have called for urgent action. And this is the reason why during the UN high-level week we took the initiative to the P5 +4 meeting – the 5 permanent members of the UN Security Council + Germany, Sweden, Kuwait, and the European Union – covering both the political and humanitarian situation as well as a dedicated humanitarian meeting together with the EU/ECHO (European Commission for Humanitarian Aid).

SC: I have a couple questions on the political side, and then I’ll return to the humanitarian side. So, first, to start on the political side, when Saudi Arabia launched Operation Decisive Storm in March 2015 it told the United States this was something that was going to take about six weeks. Obviously, the war in Yemen has lasted much longer than most anticipated with seemingly no end in sight. The UN has had three special envoys in five years, none of whom has been able to broker a comprehensive settlement. Given the lack of success on the ground and on the political track, is it time to rethink the UN’s approach through Resolution 2216, which has largely been the framing resolution for dealing with Yemen?

Ambassador Eneström: We strongly feel that the support to the UN special envoy is more important than ever. This is not the right time to change the strategy of the UN. What we can do is support the UN system but also do whatever we can as the international community to push the parties, because the responsibility is actually on the parties. Then of course, eventually I think it is important that the UN get a broader mandate as we go, hopefully, into a more consolidated process when it comes to peace and stability and building peace, which we of course hope we will end up in. Then you will need a more comprehensive mandate for the UN to act on the ground.

SC: Following up on what you just said, Madam Ambassador, what leverage do you believe the international community, the UN, and Sweden have on the warring parties, particularly the Saudi-led coalition and the Houthis, in Yemen? How can you put more pressure on them, or use the leverage that currently exists to bring them closer to peace?

Ambassador Eneström: I think it is extremely important for us and for others in the international community to keep Yemen high up on the agenda, both on the political agenda and on the humanitarian agenda. We think we need to continue with the messaging and the pressure on the parties. We have seen that has an effect when the international community continues to message and have meetings and continues to press the parties from different angles. I said already that we strongly believe that we should give the special envoy our full support, and it is important of course that he has the support of the Security Council. On this we see that there are a lot of questions about the unity of the Security Council at the moment, but when it comes to Yemen there is good common ground among the P5. When I talk about my own country, we sense that we have trust from all parties. We had the meeting in Stockholm a couple of years ago. We also have good relations with the regional actors. I think it is important that we, and others in the international community, make it clear that we will support peace and a UN-brokered peace agreement. We would do that financially, we would do that politically, and we would do that with good offices. And we would link that with the humanitarian support we are giving, and potentially development cooperation support. Of course this country will need huge investment after there is a peace agreement to build a stronger country.

SC: Yemen is sometimes described as having a “Humpty Dumpty” problem — that it is broken with little hope of ever being put back together. Given the political divisions among the Houthis in the north, Hadi’s government in exile, the Southern Transitional Council, and a multitude of armed groups, is the international community capable of holding together a country these various groups seem intent on breaking apart?

Ambassador Eneström: I think we don’t have a choice as an international community. We need to continue to push for that because, of course, we cannot accept that it will be the different armed groups in Yemen that will decide the future of the country at the expense of the welfare and rights of the broader population. We strongly believe that you need to have an inclusive peace process that brings together all the different Yemeni actors. This is what we need to support. As I said, we also believe [in] bringing women into that process. We see not only in Yemen but in other conflicts that if you involve women from the beginning of the implementation of a peace agreement, you will have a much more sustainable peace. But of course, we as the international community have a responsibility to continue to push, and to continue to be active, and to continue to push the parties. Ultimately, it is their responsibility. We cannot accept that they do not take their responsibility in building peace.

SC: If we turn to the humanitarian side, earlier this year the United States found itself in a difficult situation. That is, it wanted to continue to put humanitarian aid into northern parts of the country where the Houthis were in control, but felt that by doing so it was unnecessarily strengthening the Houthi’s political control in the north. That is humanitarian aid, which is supposed to be non-political, was having political ramifications on the ground by strengthening the Houthis. The US made a decision to partially withdraw its aid from Houthi-controlled territories. When Sweden is looking at humanitarian aid to Yemen, and is confronting similar questions, how does Sweden make a decision about where the money goes in Yemen and how to give life-saving humanitarian aid without unnecessarily shifting the battlefield or putting your finger on the scale?

Ambassador Eneström: When we give humanitarian support, we give it to the UN and we try not to earmark our support. We have great trust in the UN — and other organizations like the International Committee of the Red Cross or NGO:s — and their decisions when it comes to humanitarian support. The way we work is mostly through the UN. For us, it is extremely important that this aid is reaching the people in need and that it’s done in accordance with humanitarian principles. Access, which is a problem, is extremely important, so humanitarian actors will get access to the people to deliver the support. We do not want to politicize any humanitarian support. It is important that it reaches the people on the ground. Sweden and ECHO are hence very active within the donor community for Yemen in trying to address the obstacles within the humanitarian response.

SC: It is kind of hard, isn’t it? If you look at the US’s perspective, or even the World Food Programme’s negotiations with the Houthis up in the north, where if one side is keeping the aid non-political, and the other side is trying to manipulate it, then the World Food Programme or USAID is sort of held hostage. The only alternative they have is to withdraw aid, which no one wants because then you have preventable deaths.

Ambassador Eneström: I agree, but again, this comes back to the pressure we need to put on the parties. They have the responsibility for their own population. I totally agree with you that this is a difficult problem, which we have and will also face elsewhere with our humanitarian support. But I think here we need to continue to be strong on the messaging that we need humanitarian access, and that humanitarian assistance should be non-political. This is about people on the ground.

SC: It is fairly easy to imagine a scenario in which six years down the road the status quo remains in Yemen: The war has gotten worse while negotiations to end it remain at an impasse, while the humanitarian situation continues to deteriorate and people continue to die of preventable causes. It’s a scenario that is quite frightening if you look at the humanitarian cost. What, if anything, can the international community do to avoid such a scenario, given the fact that all the things that have been tried — from sanctions on the Houthis to special envoys who have the full and undivided support of the UN Security Council — have not, at least to this date, resulted in any sort of change or a comprehensive cease-fire? In 2016 it seemed that the Kuwait peace talks had some positive momentum, and then they were scuttled by one side. And it seems like that happens most of the time; there is a little step forward, and then there are two or three steps back. In this scenario, does the international community, the United Nations, the Security Council, just continue to do what it’s been doing and hope that something changes on the ground, or is there something else that the international community can do to make sure we don’t have six more years of what’s happened so far?

Ambassador Eneström: Not an easy question to answer. I think we need to keep it high on the agenda, and I think we need to push for the Security Council to be united on this. What we have done is also to try to get a group together where we see that we join hands with the permanent members of the security council together with some countries that we hope can push and also build bridges. The regional context is extremely important. We see that countries like Sweden, Germany, and Kuwait, together with the European Union, can try together with the P5 to push. I think this is what we need to continue to do. I agree with you that this situation is very dire, but I think we need to continue with the strategy we have from the international community. We need to continue to push and have it high up on the agenda. We need to link the political situation to the humanitarian situation, and we need to work with the region.

SC: We are almost two years out from the Stockholm Agreement, and I am curious about how you evaluate the success, or lack thereof, of that agreement. Also, looking forward, what is Sweden’s policy toward Yemen beyond the Stockholm Agreement or co-hosting pledge conferences? Is there anything else that Sweden would be looking to be pushing to the forefront here?

Ambassador Eneström: I think the Stockholm meeting was a good meeting in the sense that we had the Stockholm Agreement, we had all the parties there and we averted hostilities in Hudayda which could have had disastrous consequences. Of course we had hoped that the implementation of the Stockholm Agreement would be faster than what we have seen. That’s also a part of what we and the international community are trying to do, to continue to push for the implementation of the Stockholm Agreement. I think we need to hang on to these agreements that we have and push for them. We are willing to use our good offices if that is what can help the process move forward. I think if we are looking ahead, we hope that there will be a peace agreement that will be negotiated by the UN. From a Swedish perspective, it is important that we continue to keep our attention to Yemen, because as we discussed before, there is not only the humanitarian needs on the ground, but there are also other needs when it comes to building institutions and looking into development cooperation and other support. I think this is one of the similarities we talked about with Afghanistan. To keep the international attention on the conflict I think is extremely important.

SC: How do you do that in a world that is in a pandemic with COVID, there’s the peace talks with the Taliban in Afghanistan, there’s Iraq and what’s happening there, there’s Libya, there’s the ongoing war in Syria, and that’s just mostly in the Middle East? I have great sympathy for those at the UN who are trying to manage all these crises. All of these crises in one way or another should be at the top of the world’s attention list, and they are all fighting for space. When it comes to Yemen, how do we do what you’re advocating for, to keep the international attention on this conflict as a way of moving the parties towards peace?

Ambassador Eneström: I agree there are a lot of things where the international community needs to keep its attention right now. But I think when it comes to a country like Yemen, it is a shared responsibility of the international community and the regional actors. Those conflicts have a regional impact and a global impact, so when we look at how we can build stability, even for our continent, we need to sustain our responsibility. It’s not only the responsibility of Sweden; it’s the responsibility of the entire international community. Some countries will be more involved than others. We see that the European Union, with all its member states, is already a very strong actor. This is a shared responsibility for the international community to not leave these countries.

Arts & Culture

Salma: The Misery of Tin

By Rim Mugahed

Editor’s note: As the Yemen Review is re-launching as a monthly magazine, we are pleased to begin publishing fiction, poetry, and book reviews from Yemeni authors. Our first selection is an excerpt from Rim Mugahed’s forthcoming untitled novel, which deals with the social costs women face in war.

Salma was avoiding her father’s calls. Her mother had not yet told her whether she should inform him about the real reason they had suddenly taken off to visit her mother’s family on the city’s outskirts, or whether she should come up with a lie. He had called twice so far, and she knew she had to pick up the phone the third time he called or he’d lose it and the situation would take a turn for the worse. She gazed at her mother, who was surrounded by relatives, embracing them and kissing her grandmother’s forehead, but decided to wait until things were calmer before asking her what to tell her father.

The family lives in four separate structures that are separated by a narrow dirt path. The last building in the camp is the largest, and it’s where Salma’s grandmother, her two uncles and their wives and the children live. There are three rooms made of concrete brick and another of tinplate, and it’s here where the older children sleep. The small space that separates each room is used to store things, from cleaning tools to clothes. There are two kitchens equipped with a gas cylinder and a stove burner, which are shared by all of the women, in addition to the wood stoves. The bathroom is made of brick, with an old red curtain as its door. Unlike the layers of sand that constitute the floor of the house, the bathroom floor is made of concrete. Salma’s aunts and another uncle live in the building next door. The third structure is made up of one room, while the fourth has two. They’re built from concrete brick and lack doors, with nothing but worn out rags shabbily hanging for some privacy; their roofs are tin or wood and sand, all strewn with punctured car tires.

Salma found herself on the roof, unaware of how she got there or why. She stood there surrounded by shards of rusting tin-coated steel, torn cloths and the remains of metal tools that could come in handy for someone, someday. The children were outside as usual, getting dirty playing in the mud – seemingly indifferent to what had happened the night before, as children are to things they cannot comprehend. Salma gazed at her 12-year-old cousin, who seemed disoriented. Her grandmother said she had intuitively hidden her when the men approached the house. However, the adults in the room were not concerned about hiding what had happened, speaking openly without even noticing she was standing there.

Overwhelmed by curiosity and overtaken by fear, Salma’s mother kept asking for details that she did not want to believe. Salma had already told her about news circulating on WhatsApp, that armed men had stormed the camp of the internally displaced and Muhamasheen at night, forcing men out of the houses and raping and molesting the women they had kept inside. Horrified, Salma’s mother broke down in tears while Salma remained calm, having already pondered what happened and concluded: Of course this would happen! What would prevent this from happening? Hasn’t this happened throughout time in every corner of the world? If we would only take a look through history, we would realize that men have created war and women have paid the price, in victory and in defeat. And, therefore, in this loathsome society, women, like Salma and her mother’s family before her, would be the first ones to pay the price of war.

They were all talking at the same time, challenging the accounts of that night’s events, screaming, soothing one another, praying, then breaking down in tears. Her aunts’ husbands and one of her uncles were narrating what had happened to the men. Then they’d listen to the women, often interrupting them and forbidding them from recounting their experience, then exploding in anger, swearing and kicking whatever was lying around before sitting again to hear more details.

Salma sat in the corner on an empty ghee container, which she had made sure was not greasy so it would not stain her abaya. The room was brightly lit and the cool night’s breeze had swept in, but in her eyes, it was the most miserable room in the world: worn out and dirty blankets, old mattresses, kitchen utensils, old shoes and many other items her mother would never tolerate hoarding in her own house. She opted out of the conversation as everything had become pointless since her meeting with Ali, and having survived that night she had promised God that she would not complain. She sat there, adamant not to break her silence, having taken an oath not to speak. But she gathered the details of that night’s events, imagining it in Ali’s prosaic words and unrefined tone:

“Cars filled with gunmen from the forces tasked with maintaining order in the stricken city stormed the houses and camps of internally displaced people and the Muhamasheen, in the black moonless night when the power was out. Testimonies of dragging men away from their houses, insulting them and humiliating them under the pretense of not having identity cards. Molestation and rape of women who were with their children in the shabby houses on the city’s outskirts. M.S, a woman in her 30s (Salma imagines the testimony of her youngest aunt): ‘A man asked me for my ID. I told him I did not have one and that we never had one. He started touching me, and when I screamed, he slapped me and said he would tear my clothes if I screamed again.’ M.H. said (Salma imagines the sharp voice of her eldest uncle’s wife): ‘Two men tossed me around in each other’s lap.’ When asked about cases of rape, female witnesses said they heard women scream in neighboring houses, and they were certain they were raped but no one has spoken about this yet, afraid of the scandal that is expected and normal in a society like ours.”

Salma felt repulsed as she imagined the journalists interviewing her naïve aunts, rudely insisting on hearing the most accurate details to get a story that attracts readers. “Where exactly did he touch you, dear? Were you in your nightgown when the armed men stormed the house? Did the armed men molest little girls? Since you, ma’am, were not raped like your neighbor, do you think there was a reason you were spared a similar fate?”

Most people spread videos on WhatsApp and asked others to send more; that’s what Salma hated the most. Salma knew for a fact that her aunts and uncles would speak to these petty journalists, because like anyone else in the world without an ID, they would finally be able to prove their existence – even if only briefly – via an interview recorded on a smartphone by people who know nothing about them. They’d speak even without knowing the purpose of these video recordings, which would never be used to achieve justice. This is exactly what Salma wanted to say, but she could not rub salt into their wounds and humiliate them even more: “My dear uncles and aunts, these fools with their smartphones will not remember any of you after publishing the videos on social media platforms. You are so far from being significant in any way for anyone at all to care about you, you are of no worth in this miserable world even if you are raped every day. Rape is considered a crime of honor and by national standards, you have no honor, no dignity – your existence is null and void.”

Salma will never say this, but she is so painfully aware of it.

Her father was calling now for the third time. She ran to her mother and asked in whispers what to tell him. It usually takes some time for her mother to make up her mind, but not this time. She immediately told Salma: “Tell him your grandmother is sick.” Salma sneaked out and walked toward the outskirts of the camp so her father would not overhear the family’s loud conversation. She did not know why her mother lied, but she had expected it and that’s why she had asked her. When she hung up the phone, her cousin was standing behind her. Without hesitation, she looked Salma straight in the eye: “I saw everything! My mother and grandmother are lying.”

Salma felt a hole open up inside her as she asked: “Will you tell me what happened?” Unhesitatingly, and as if she had already made up her mind to do so before Salma even asked, she recounted that night’s events. Tears streamed down Salma’s face through each detail, unable to decide which pained her the most. The child had witnessed through a little hole in the roof what the women did not confess.

As her cousin finished speaking, Salma asked one last question: “Will you tell anyone else about this?” “No, I cannot,” the girl replied.

Rim Mugahed is a non-resident researcher at the Sanaa Center. She is at work on her first novel.

Editor’s Note: This piece was originally published in Arabic in As-Safir Al-Arabi.

This report was prepared by (in alphabetical order): Naziha Baassiri, Ryan Bailey, Ali Al-Dailami, Yasmeen Al-Eryani, Ziad Al-Eryani, Magnus Fitz, Amani Hamad, Hamza al-Hammadi, Waleed Alhariri, Abdulghani Al-Iryani, Gregory Johnsen, Maged Al-Madhaji, Farea Al-Muslimi, Spencer Osberg, Hannah Patchett, Hussam Radman, Susan Sevareid and Abubakr al-Shamahi.

The Yemen Review is a monthly publication produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. Launched in June 2016 as ‘Yemen at the UN’, it aims to identify and assess current diplomatic, economic, political, military, security, humanitarian and human rights developments related to Yemen.

In producing The Yemen Review, Sana’a Center staff throughout Yemen and around the world gather information, conduct research, and hold private meetings with local, regional, and international stakeholders in order to analyze domestic and international developments regarding Yemen.

This monthly series is designed to provide readers with contextualized insight into the country’s most important ongoing issues.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security-related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Endnotes

- “Scores More Freed on Day Two of Yemen Prisoner Swap,” AFP, October 16, 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/scores-more-freed-on-day-two-of-yemen-prisoner-swap-01602860404

- Dion Nissenbaum, “Two Americans Held Hostage by Iran-Backed Forces in Yemen Freed in Trade,” Wall Street Journal, October 14, 2020,

- “New ‘ambassador’ in Sana’a signals Iran’s ambitions in Yemen,” The Arab Weekly, October 18, 2020, https://thearabweekly.com/new-ambassador-sanaa-signals-irans-ambitions-yemen

- Office of the Special Envoy for Yemen, Twitter post, “The Office of the Special Envoy for #Yemen denies involvement in the transfer of Hassan Irloo into #Sanaa…,” October 18, 2020, https://twitter.com/OSE_Yemen/status/1317801932736561153

- “Yemen submits UN complaint after Iran posts ambassador to Houthi-held Sanaa,” The New Arab, October 20, 2020, https://english.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2020/10/20/yemen-submits-un-complain-over-irans-ambassador-to-houthis

- Morgan Ortagus, Twitter post, “The Iranian regime smuggled…”, October 21, 2020, https://twitter.com/statedeptspox/status/1318889792906690562?s=20

- “Houthi Official Gunned Down in Capital,” Reuters, October 27, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-idUSKBN27C1GP

- Ali Mahmood Mohammed, Twitter post, “For the third day, angry officers…,” September 29, 2020, https://twitter.com/alimahmood19844/status/1310952139624194051

- “With the efforts of the governor Lamlas, the military suspends its sit-in and opens the port’s gate [AR],” Hadramout21, October 12, 2020, https://www.hadramout21.com/2020/10/12/262494/.

- Sana’a Center interviews with local sources who track fuel dynamics in Hudaydah and Sana’a on October 26, 2020.

- Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “Yemen Economic Bulletin: Another Stage-Managed Fuel Crisis,” July 11, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/10323

- Sana’a Center interviews with a government official and a fuel industry researcher in Aden in September and October 2020.

- Sana’a Center interviews with local sources who track fuel dynamics in Hudaydah and Sana’a on October 26, 2020.

- “First State by al-Kurami Bank after being shuttered by the Houthis,” (Ar.) al-Mashhad, October 1, 2020. https://www.almashhad-alyemeni.com/180488

- “Their crime shocked the Yemenis… the execution of the Al-Aghbary killers… [AR],” Al Arabiya, October 17, 2020, https://www.alarabiya.net/ar/arab-and-world/yemen/2020/10/17/

- “200 Death Sentences Issued by the Houthis-controlled Courts,” SAM Organization for Rights and Liberties, October 10, 2020, https://samrl.org/l.php?l=e,10,A,c,1,74,77,3972,php/200-Death-Sentences-Issued-by-the-Houthis-controlled-Courts

- World Health Organization—Yemen, Twitter post, “During the first 9 months of 2020, 197,377 suspected #cholera cases were reported in #Yemen…,” October 14, 2020, https://twitter.com/WHOYemen/status/1316261235156025345