Contents

- State of the War

- The Political Arena

-

Economic Developments

- Collapse of Yemeni Rial Fueling Unprecedented Transfer Costs

- CBY-Aden Board of Directors Replaced

- CBY-Aden Auctions Foreign Currency in Failed Attempt to Stave Off Inflation

- Hadi Appoints New Heads of Yemen Petroleum and Aden Refinery Companies

- Al-Mokha Port Expansion Plans

- MTN Group Exits Yemen in Controversial Deal

- Seeking a Course Correction in the Yemen Humanitarian Response – By Sarah Vuylsteke

- The Case for Mukalla as Yemen’s Capital – By Farea Al-Muslimi

- Has Riyadh Woken Up From Its Al-Mahra Pipe Dream? – By Yehya Abuzaid

- An Unneighborly Rapport: How Yemeni-Saudi Relations Went Astray – By Abdulghani Al-Iryani

- An Endless Pursuit of Refuge – By Manal Ghanem

- Development Assistance in Yemen: A Cautionary Tale from Al-Mahra – By Ameen Mohammed Salmeen ben Asem

- IDPs in Hudaydah: Where Aid, Protection Don’t Always Reach – By Ansam Ali

November at a Glance

State of the War

By Abubakr al-Shamahi

Coalition Falls Back in Hudaydah, Fighting Shifts South

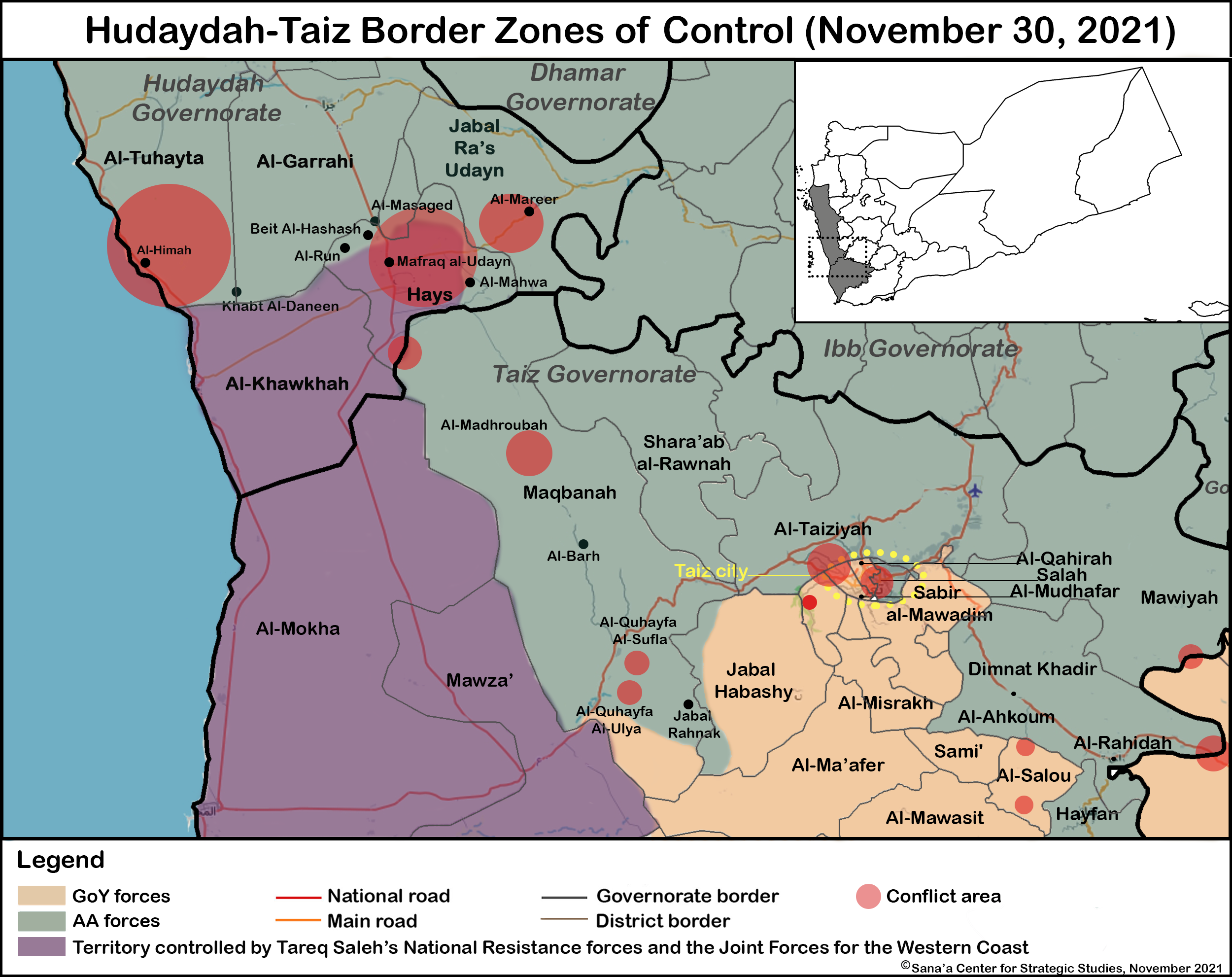

A surprise decision by the UAE-backed Joint Forces to withdraw from areas south of Hudaydah city and the surrounding governorate shook up the military situation on Yemen’s Red Sea coast.[1] The largest members of the Joint Forces are the Giants Brigade, Tariq Saleh’s National Resistance Forces and the Tihama Resistance. The withdrawal, which began on November 9, saw the Joint Forces move out 15,000 fighters and abandon frontlines in Hudaydah city, home to Yemen’s busiest port, as well as in Al-Durayhimi and Bayt al-Faqih districts, and from the majority of Al-Tuhayta district. The frontlines had been active but largely static since the December 2018 UN-sponsored Stockholm Agreement, which ended a Saudi-led coalition push to take Hudaydah city.

The UN and the Yemeni government said they had no advance notice of the withdrawal,[2] and it appeared as though the Joint Forces’ own units were confused about how it would be carried out. The process was disorganized, with units disputing the order of withdrawal with one another. Houthi forces took advantage of this, shelling Joint Forces positions and causing dozens of casualties, according to local military sources. Hundreds of Joint Forces fighters were captured by Houthi forces.

The Joint Forces withdrew to the south, establishing a new defensive line from the Al-Himah area, in southwestern Al-Tuhayat district, to Hays district, about 40 kilometers to the east. The official explanation from the Joint Forces was that the withdrawal corrected what it called the “mistake” of remaining in defensive positions while frontlines elsewhere in Yemen needed support.[3] In effect, the terms of the Stockholm Agreement prevented the Joint Forces from making any serious attempt to advance in Hudaydah since 2018.

Redeployment and the Hays Offensive

Once the Joint Forces had organized in its new positions, it quickly went on the offensive into different Houthi-controlled areas.[4] Backed by Saudi-led coalition airstrikes, the Joint Forces captured the remainder of Hays district on November 19, including Mafraq al-Udayn, which links Ibb and Hudaydah governorates and is a main supply route for Houthi forces into both governorates and on to western Taiz. The advances marked the first time that any anti-Houthi force held high enough ground to overlook areas of Ibb since the governorate was taken by the Houthis in 2015. The Joint Forces also consolidated control over Al-Khawkhah district in southern Hudaydah governorate, and advanced into Taiz governorate’s Maqbanah district with the aim of taking its capital, Al-Barh.

But these advances were ultimately the high watermark of the Joint Forces’ November offensive, as the Houthis began to reverse their losses. Saudi-led coalition airstrikes decreased markedly in intensity in the last ten days of the month, precipitating the withdrawal of the Joint Forces on November 24 from recently captured areas in southern Al-Garrahi district, according to local sources. On November 27, Houthi forces advanced, capturing areas in northern Hays district, including the villages of Al-Akhdam, Al-Ashjar, Al-Mahwa, Bani Jarbah and Hijamah.

Clearly, the leadership of the Joint Forces has decided to pursue a new strategic direction. This will likely entail an attempt to take Houthi territory in western Taiz governorate, which could lead to confrontations with Islah-affiliated Yemeni government forces in other parts of Taiz.

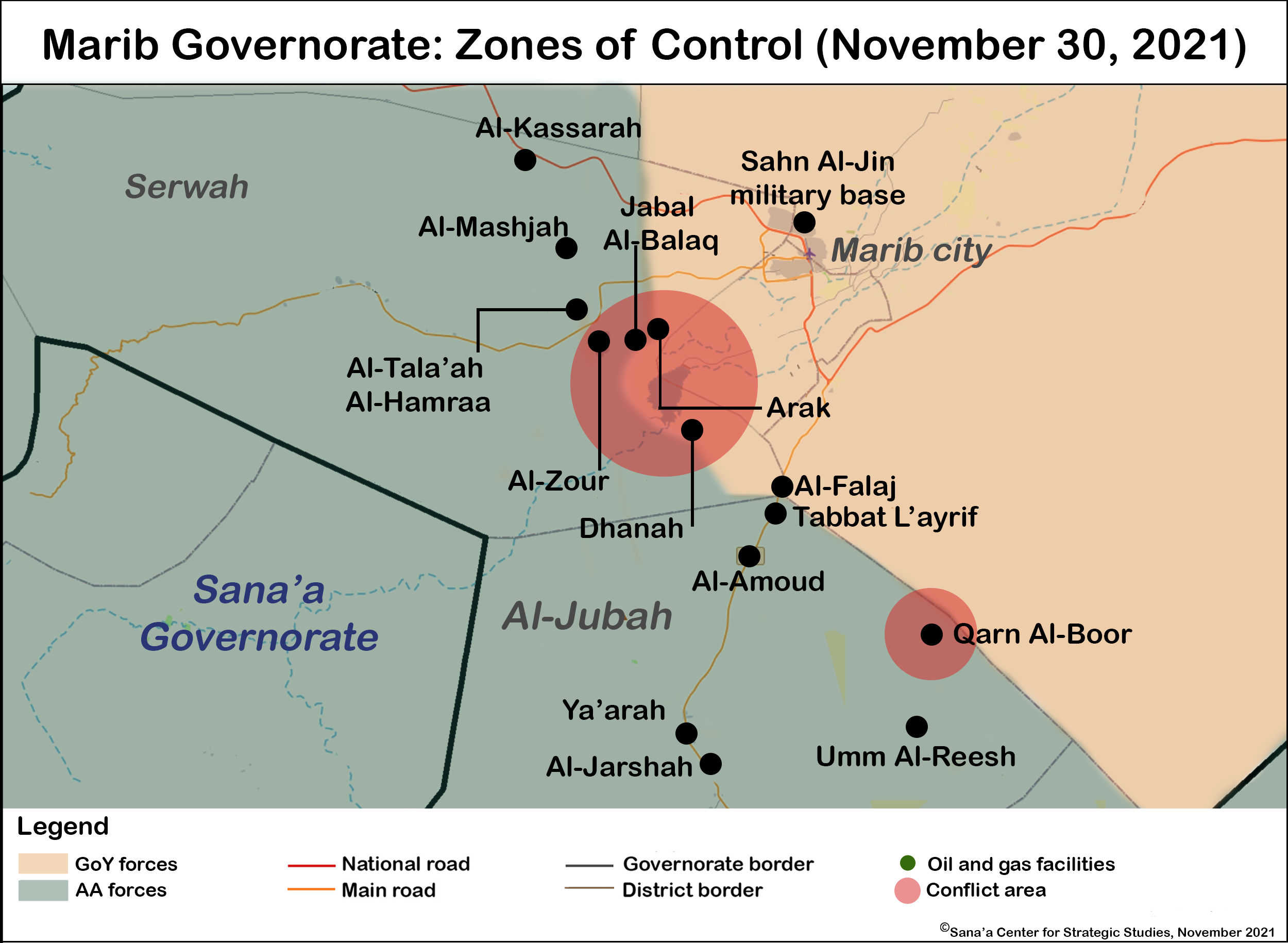

Houthis Continue Advance on Marib City

The focus of both the Houthis and the Saudi-led coalition on the Red Sea coast led to a reduction in the intensity of hostilities in Marib governorate in the latter part of November. The Houthis had been building on gains they made in recent months, advancing toward Marib city from the west and the south. On November 2, Houthi forces took Arak area, southwest of Marib city, after heavy clashes with Yemeni government forces, and captured the mountains overlooking Al-Rawdhah, a residential suburb of Marib city, according to fighters from both sides. On the same day, Houthi fighters captured the Umm Al-Reesh military camp to the south of Marib city in southeastern Al-Jubah district. On November 7, the village of Al-Amoud fell to Houthi forces after weeks of fighting,[5] and the Tabbat L’ayrif area, 20 kilometers south of Marib city, was captured on November 14.

With the help of the Saudi-led coalition, Yemeni government forces have largely held their ground since then as casualties were piling up on both sides. On November 18, the Saudi-led coalition claimed to have killed 200 Houthi fighters in the preceding 24 hours, and stated that 27,000 Houthi fighters had been killed in the battle for Marib since last year.[6] Two Houthi officials confirmed that nearly 15,000 of their fighters had been killed in Marib since mid-June.[7]

Abubakr al-Shamahi is an editor and researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

The Political Arena

By Casey Coombs

Pressure Grows on Islah-Affiliated Shabwa Governor to Resign

On November 16, Sheikh Awad Mohammed bin al-Wazir al-Awlaki, a General People’s Congress (GPC)-affiliated member of parliament, held a meeting near Shabwa governorate’s capital of Ataq to demand the dismissal of Shabwa governor, Mohammed Saleh bin Adio, the implementation of reforms at the local authority and the unification of efforts to liberate districts captured by Houthi forces in September. Al-Awlaki, who comes from the influential Al-Awalaq tribe in Shabwa, had returned to Shabwa in early November after living in the UAE for the last six years.

Military forces aligned with Bin Adio, who is a member of the Islamist Islah party, arrested prominent tribal and local figures traveling to and leaving the meeting in the Watah area between Ataq and Nusab districts. Sheikh Omar Atef al-Mazaf, another leader in the GPC in Shabwa, was arrested after returning from the meeting, according to Al-Mazaf’s relatives. On November 15, government forces opened fire on members of the Laqmoush tribe when they were on their way to the meeting. Four members of the 2nd Mountain Infantry Brigade and Special Forces were wounded in the ensuing clashes, according to a tribal source.

Hundreds of people established a peaceful sit-in in Nusab after the November 16 meeting; the group also expressed its intent to set up a protest camp in Ataq.

At another meeting Al-Awlaki headed on November 25, the formation of an organizing committee was announced for a series of open sit-ins planned in all districts of the governorate, including Ataq. In response to the plans to establish a sit-in camp in Ataq, government forces were stationed in the Al-Oshah area between Nusab and Ataq districts.

The Southern Transitional Council (STC) has also increased its calls for the removal of Bin Adio in recent months, while Southern Resistance forces affiliated with the STC have launched attacks on Ataq Military Axis soldiers. STC officials have accused the Islah-affiliated governor and the Ataq Military Axis of facilitating the Houthis’ takeover of Ain, Bayhan and parts of Usaylaan district.

Developments in Government-Controlled Territory

Marib Political Parties Condemn Handling of Houthi Attacks

On November 1, the local representatives of several political parties in Marib published a letter criticizing the national, regional and international responses to the ongoing Houthi military advances in the governorate. The letter specifically mentions the targeting of unarmed civilians with ballistic missiles and drones, which has caused a mass displacement of residents. The signatories of the letter – the Islah, GPC, Socialist, Nasserist, Baath and Al-Rashad Union parties – expressed disappointment in the “shameful silence” of the UN Security Council, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the UN and US envoys for their failure to help the civilians displaced by the fighting. The parties added that the internationally recognized government’s leadership and the Saudi-led coalition had failed in managing the battles against the Houthis. More broadly, the legitimate government had “failed miserably in its responsibilities in all various levels, politically, militarily, economically and in the media field,” the letter said. The political parties ended the letter by calling on the people of Marib in particular and the free people of Yemen in general to mobilize and use all local and national resources and capabilities to defend Marib and unite against the Houthis nationwide.

Human Rights Watch catalogued Houthi ballistic missile strikes that have targeted civilian locations in Marib since October, including an attack on the Dar al-Hadith Salafi school and mosque in Al-Amoud village in Al-Jubah district that killed 29 civilians, and another missile that targeted the home of prominent Murad tribal sheikh Abdulatif al-Qabli Nimran, killing at least 12 civilians including children. Between August and November, nearly 100,000 people in Marib have been displaced due to the fighting, according to the governorate’s Executive Unit for IDP management (for more on IDPs in Marib, see ‘An Endless Pursuit of Refuge‘).

Car Bomb Targets Journalists in Aden

On November 9, an explosive device planted in the car of two Yemeni journalists detonated while they were driving through Khor Maksar district in Aden. The explosion killed Rasha Abdullah, a correspondent for Al-Sharq channel in Aden, and her unborn child, and severely injured her husband Mahmoud Al-Atmi, a journalist with Al-Arabiya TV. A journalist in Hudaydah who knew the couple posted an SMS correspondence he had had with Al-Atmi in October in which the latter said the Houthis were summoning colleagues to find out where he and his wife were living in Aden, their movements and what kind of car they drove. Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed called the incident a terrorist attack.

Developments in Houthi-Controlled Territory

Houthis Occupy US Embassy, Detain US and UN Employees

On November 11, a spokesperson for the US State Department said that the “majority” of the 25 Yemeni employees of the US embassy in Sana’a who had been kidnapped by the Houthis had been released. The employees, most of whom were security guards protecting the compound, had been detained by the Houthis over a three-week period prior to the State Department’s acknowledgment of the detentions. The spokesperson also acknowledged that the Houthis had broken into the embassy and called on them to vacate the premises and “return all seized property.”

The embassy was evacuated in the months after Houthi forces captured Sana’a in a coup in September 2014. The American ambassador and key staff relocated to Saudi Arabia, where the diplomatic mission to Yemen has since been based.

On November 17, UN spokesperson Stephane Dujarric announced that the Houthis had detained two UN employees “without any justification or charge” in the capital Sana’a. The employees, who were understood to have been working in the UN’s cultural and human rights divisions, were detained separately on November 5 and 7 and have been held without access to their families or co-workers.

Houthi Court Sentences Model to 5 Years After Sham Trial

On November 7, the Houthi-run Specialized Criminal Court in Sana’a sentenced Yemeni model and actor Intisar al-Hammadi to five years in prison for “violating public morals.”

Three other women who were arrested with Al-Hammadi on February 20, 2021, while driving to a photo shoot in Sana’a were sentenced to one, three and five years, respectively, on the same charges. During her eight-month detention, Al-Hammadi was regularly abused by prison guards, threatened with a forced virginity test and compelled while blindfolded to sign a pre-written statement regarding drug-related offenses. She later attempted suicide after being transferred to the “prostitution” section of the Central Prison. Houthi authorities suspended Al-Hammadi’s lawyer before her first court appearance and replaced a prosecutor who ordered Al-Hammadi’s release after concluding she was not guilty of a crime.

The Houthis’ arrest and conviction of Al-Hammadi in a sham trial is part of a broader pattern of ongoing women’s rights abuses under Houthi rule, including the creation of an all-women militia (al-Zainabiyyat) to crack down on women political activists, increasing gender segregation in universities and businesses, expelling women from the workforce and preventing access to contraceptives.

Al-Hammadi’s relatives told Human Rights Watch that she was the sole breadwinner for her family of four, including her blind father and her brother who has physical disabilities.

Houthi Officials: Nearly 14,700 Soldiers Recently Killed in Marib

On November 18, unnamed Houthi officials told Agence France Presse that nearly 15,000 of their fighters had been killed since mid-June on the frontlines in Marib governorate. Although it is known that the Houthis have sustained greater losses than the internationally recognized government and allied tribal fighters in Marib, there has been little information on the number of Houthi fatalities during the Marib battles. Earlier, a Saudi-led coalition spokesperson said that 27,000 Houthi fighters had been killed in the battles in Marib since last year.

International Developments

Omani Minister Says the Sultanate is Considering Saudi Pipelines to Arabian Sea

On November 2, in an interview with Saudi-owned newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat, Oman’s Minister of Economy Dr. Said Mohammed al-Saqri called for the revival of a project to build overland oil and gas pipelines linking Saudi oil fields to an export terminal on Oman’s Arabian Sea coast. The news coincided with redeployment of Saudi soldiers from several bases in Yemen’s Al-Mahra governorate. In recent years, Saudi Arabia is rumored to have been considering plans to build such a pipeline through Al-Mahra. However, anti-Saudi factions in the eastern Yemeni governorate have strongly opposed the idea. (See further commentary, see ‘Has Riyadh Woken Up From Its Al-Mahra Pipe Dream?’)

UN, US Envoys Visits Taiz, Aden

On 11 November, the UN Special Envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, concluded a three-day visit to Taiz governorate. Grundberg met with local authority officials and military commanders in Taiz city, Al-Turbah and Al-Mokha. Hours before Grundberg arrived in Al-Mokha to meet with the commander of the National Resistance forces, Tareq Saleh, Houthi missiles struck an uninhabited part of the city. The missile strikes were a signal of the Houthis’ disapproval of the meeting and an attempt to prevent it from happening, according to a spokesperson for Saleh. Grunberg’s visit marked the first to Taiz by a senior UN official since the beginning of the war.

Prior to the visit to Taiz, Grundberg held meetings with the internationally recognized government’s Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed and Foreign Minister Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak in Aden. On November 9, the US Special Envoy for Yemen, Tim Lenderking, also held talks with Maeen Abdelmalek and Bin Mubarak in Aden. Their discussions included efforts to end the war, the Houthi offensive on Marib, the Riyadh Agreement and the economy.

UN and US Sanction Houthi Commanders

On November 9, the UN Security Council’s 2140 Sanctions Committee designated three Houthi commanders. Muhammad Abd Al-Karim al-Ghamari, Chief of the General Staff of the Houthi armed forces was sanctioned for directly threatening the peace, security and stability of Yemen in his role overseeing the Houthi military offensive in Marib and involvement in cross-border attacks against Saudi Arabia. Yusuf al-Madani, commander of the Fifth Military Region along Yemen’s western coast, was designated for threatening the peace, security and stability of Yemen. Al-Madani, who is married to one of the daughters of the deceased founder of the Houthi armed movement, Hussein Badreddine al-Houthi, also plays a leading role in the military offensive in Marib. Saleh Misfar Saleh al-Shaer was designated for smuggling weapons in his capacity as deputy minister of defense for logistics, as well as for extorting and detaining Yemeni citizens in his role as “Judicial Custodian” to fund the war effort. Al-Shaer used the Specialized Criminal Court to confiscate more than $100 million worth of funds and assets from the Houthis political opponents.

The US Treasury Department previously designated Al-Ghamari and Al-Madani in May 2021. On November 18, the US added Al-Shaer to its sanctions list for similar reasons the UN cited in designating him earlier in the month.

Yemen VP Visits Doha

On November 29, Yemeni Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar arrived in Doha for a three-day state visit. The trip marked the first visit by a senior Yemeni official to Qatar since 2016, prior to the three-year Saudi-led boycott of Doha that was lifted earlier this year. During the visit, Al-Ahmar delivered a letter from President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi to Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, and met with Prime Minister and Minister of Interior Sheikh Khalid bin Khalifa al-Thani. Mohsen also attended the opening ceremony of the FIFA Arab Cup.

Casey Coombs is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and an independent journalist focused on Yemen. He tweets @Macoombs

Economic Developments

By the Sana’a Center Economic Unit

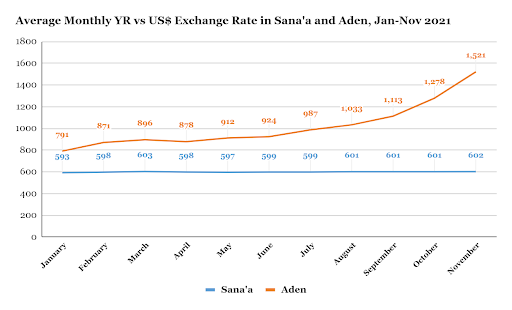

Collapse of Yemeni Rial Fueling Unprecedented Transfer Costs

The Yemeni rial (YR) continued its historic depreciation in areas controlled by the internationally recognized government in November. At the beginning of the month, one United States dollar (US$1) could buy roughly YR1,435 in Aden; by November 30, the exchange rate was YR1,620 to the dollar, and the rial looked set for further losses. With the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) essentially crippled and unable to carry out basic monetary functions, it has been unable to head off the currency’s collapse. It attempted to intervene in November by launching new foreign currency auctions (see below), but the impact on the exchange rate was negligible.

Concurrently, firms providing money transfer services have been dramatically increasing their customer fees for transactions from government-controlled to Houthi-controlled areas. At the end of November, the Sana’a Center Economic Unit found that the cost of transferring Yemeni rials from Aden to Sana’a had reached 180 percent of the transferred amount.

CBY-Aden Board of Directors Replaced

In early December, the internationally recognized Yemeni government replaced the board of governors at the CBY-Aden, in a belated response to long-standing appeals from local and international stakeholders to do so. In November 2020, local media published a report leaked from the Central Organization for Control and Accounting that accused the bank’s senior leadership of venality and corruption. The integrity and performance of CBY-Aden’s board of directors and senior leadership then faced intense international scrutiny following the release of the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen’s annual report on January 25, 2021. In it, the panel accused the CBY-Aden of colluding to embezzle nearly half a billion dollars from the US$2 billion deposit Saudi Arabia gave to the bank in 2018 to facilitate exchange rate stabilization and import financing. The CBY has also not been subjected to external audit since the relocation of its head office in 2016.

CBY-Aden Auctions Foreign Currency in Failed Attempt to Stave Off Inflation

In November, the CBY-Aden launched a new foreign currency auction system for private banks in Yemen using the Refinitiv platform. The objective is to help the central bank create a transparent platform by which to address the depreciation of the Yemeni rial and the accompanying inflation in areas nominally under the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government. Three separate auctions were held in November, with US$15 million available for sale at each:

- Auction 1, November 10: a total of US$8,775,000 was purchased at an exchange rate of YR1,411 per US$1.

- Auction 2, November 16: a total of US$14,708,000 was purchased at an exchange rate of YR1,461 per US$1.

- Auction 3, November 23: a total of US$13, 451,000 was purchased at an exchange rate range of YR1,461.

The three tranches, totaling some US$37 million in foreign exchange auction trading, was an expensive policy choice for the CBY-Aden, drawing on its nearly exhausted foreign currency reserves. It has been almost a year since the CBY-Aden depleted the US$2 billion Saudi Arabia deposited at the bank in 2018, which had helped it to regain control of the monetary cycle and stabilize the rial exchange rate. The central bank has since lost most of its ability to intervene in the foreign exchange market, undermining its authority as a monetary institution and increasing the cost of further intervention. The November intervention was well below market demand and had a limited effect on the exchange rate. The Sana’a Center Economic Unit has estimated that a US$100 million intervention, with reasonable expectation of further currency support, is necessary in order to have a meaningful and sustainable impact.

Hadi Appoints New Heads of Yemen Petroleum and Aden Refinery Companies

Yemeni President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi issued a presidential decree on November 6, appointing Ammar al-Awlaqi as the new Executive Director of the state-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) and Mohammad Yaslam Saleh as head of the Aden Refinery Company (ARC). The appointments were made amid continued fuel price hikes in government-held areas, as reported by the Sana’a Center last month, with the ‘commercial price’ of petrol at privately-owned stations in Aden reaching YR22,000 per 20 liters in November. By comparison, the corresponding price at privately owned stations in Houthi-controlled territories was YR11,000, while the price at Houthi-run YPC stations was YR8,500.

Al-Mokha Port Expansion Plans

According to a senior official in the National Resistance Forces, planning is underway regarding the possible expansion of Al-Mokha port. In particular, the stated aims are to increase the depth of the Red Sea port, currently estimated at 7.8 meters, and to expand the wharf. Increasing the depth would enable larger commercial ships to access the port and facilitate existing activity by dhows and small and medium sized vessels, such as fuel shipments and livestock imported from the Horn of Africa. Al-Mokha port reopened on July 30, 2021 after being closed for six years during the conflict. Just a month after reopening, the port was subject to a Houthi missile and drone attack that destroyed warehouses and forced its temporary re-closure.

MTN Group Exits Yemen in Controversial Deal

On November 18, South African multinational telecommunications company MTN Group announced the completion of the transfer of its majority (82.8 percent) stake in MTN Yemen to Emerald International Investment LCC. With a reported 4.7 million subscribers, MTN Yemen is one of the largest telecommunications companies operating in Yemen alongside Yemen Mobile and Sabafon. According to MTN Group, “Emerald is a subsidiary of Zubair Investment Center LLC, an affiliate of Zubair Corporation LLC, which is the minority shareholder in MTN Yemen.” The Zubair Corporation is an Omani business conglomerate that operates in many sectors, including energy, finance, real estate, hospitality, arts and education.

The MTN Group’s sale of its Yemeni operations has drawn controversy in the local press, with speculation that Emerald International Investment is a Houthi front facilitated by the Omanis. A Sana’a Center Economic Unit investigation noted that Emerald has neither a business registration nor a license history to prove its purported affiliation with Al Zubair Corporation LLC. Available information suggests Emerald did not exist prior to its involvement in the acquisition of MTN Yemen.

Following the public announcement of the deal, the internationally recognized Yemeni government declared it was rejecting what it called “unilateral” measures by MTN Yemen to sell its majority stake without consulting the government. In a statement, the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology said MTN Yemen initiated the move without taking into account its legal obligations to pay overdue taxes and licensing fees, and that the sale violated MTN’s contractual obligations to the government. The ministry stated that it will take the necessary measures to preserve the government’s legal rights and protect Yemeni consumers using the company’s networks.

According to MTN Group, the sale of MTN Yemen is part of its recent strategy to reduce its level of engagement in the Middle East and refocus on Africa, as announced in August 2020. The announcement of the deal follows an internal review of conflict markets, such as Yemen and Syria, whereby an exit strategy would be planned for those that were not self-funding. The telecommunications sector in Yemen has suffered considerably during the conflict as a result of the destruction of facilities and the dual governance and competing tax demands of the Houthis and the internationally recognized government.

Feature

Seeking a Course Correction in the Yemen Humanitarian Response

Editor’s Note: Sarah Vuylsteke, access coordinator for the United Nations’ World Food Programme in Yemen in 2019 and author of the report series When Aid Goes Awry: How the International Humanitarian Response is Failing Yemen, spoke November 8, 2021, in Geneva about her findings. The reports, published by the Sana’a Center in October, identified challenges, poor decisions and flawed practices that have driven the international response off course in Yemen, and made numerous recommendations toward implementing an effective response. Vuylsteke’s remarks at the Geneva forum, A New Narrative on Aid to Yemen: Toward Effective Humanitarian Practice, held in conjunction with the Sanaa Center Geneva Association, and the MENA Student Initiative of the Graduate Institute, have been edited for length.

It takes on average three days to die of thirst, 14 to starve. In Yemen it takes on average 10 days and often longer to reach any given location or to roll out a lifesaving response – if we manage at all. Humanitarian aid always tries to reach those most vulnerable and affected by conflict. Women. Children. The elderly and disabled. Yet in Yemen if you belong to any of these groups you are the least likely to have access to aid and assistance.

Why?

Yemen is the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. One step away from the brink of famine. The most dangerous country in the Middle East. The humanitarian operation faces immense challenges and is grossly underfunded. Nineteen million people are hard to reach. Authorities interfere and restrict activities on a daily basis. This is the prevailing narrative of the Yemen humanitarian operation.

While this is the public side of the story, there is another side – one that does not get discussed often and rarely makes it into the news. This story is one about the failure of the humanitarian system to deliver at scale, and how it may be contributing to the continuation of the conflict, blurring the lines between international assistance and contributing to war profiteering.

The humanitarian operation in Yemen is difficult to fathom when you describe it out loud. Many aspects of it are incomprehensible and would be strongly condemned elsewhere. One person I spoke to even called it sociopathic. I certainly have seen no other humanitarian operation like it. Yet somehow the deepest and most obvious flaws have been lost within the operation, accepted due to incompetence, carelessness and self-interest.

The Houthi movement in Yemen is without a doubt ideologically extreme. It is one of the most oppressive groups the world has seen. It is a party of one of the world’s most brutal conflicts. It is a perpetrator of gross human right violations, including executions and torture. It is also our largest humanitarian partner. Every day in Yemen we entrust an organization which has every motivation to disrupt principled humanitarian assistance with carrying out principled humanitarian assistance. We even pay them for it. As a result, no humanitarian can say for sure where aid in Yemen ends up.

How far we have strayed from a principled response can be seen through the example of Durayhimi city. This small town on the West Coast in Yemen has been held by Houthi forces since the start of the war. Most residents had already fled in 2018, before an offensive that saw the town surrounded by [Saudi- and Emirati-led military] coalition forces. By 2019 only a handful of civilians remained, 100 at most. Their neighbors and captors; thousands of Houthi fighters and a few prisoners of war. Also in 2019, the UN began to receive immense pressure from Houthi authorities to bring food, medical aid and emergency supplies to the location. Voices of concern were raised, objections lodged. How could we ensure that supplies would reach civilians? How would we protect them from being targeted and aid from being appropriated? Was it not clear that the pressure and demands would go to benefit fighters, combatants? All concerns fell on deaf ears. A WFP official at the time, when confronted with the question as to who stood to benefit from the assistance stated “Of course I know the so-called families inside are military. We are going to do it anyway.” Assistance, predominantly food, was delivered for almost 2,000 people. A few months later another three-month delivery was made. This assistance likely sustained Houthi troops for months through the autumn of 2019, with the full acknowledgment of the UN. It was even hailed as a success story.

There are almost certainly major humanitarian needs in Yemen. They are likely large. I am not here to claim that needs do not exist. But if you ask me whether the humanitarian situation in Yemen is as bad as the operation claims, worse or even half as bad, I honestly cannot tell you. There are claims that should and need to be refuted. For example, despite continued claims of famine, Yemen has reportedly seen an improvement in food security over the years. Malnutrition figures are apparently not worse or even better than pre-conflict. Regardless, in reality all the data and information available is suspect. With the limited presence of aid workers, and an inability or unwillingness to be present in most parts of the country, we have turned to the perpetrators of this war and asked them to somehow provide neutral and unbiased information. We have asked authorities and national organizations in one of the poorest and most remote parts of the world to assume the responsibilities for collecting and analyzing data that would normally be reserved for the most well-resourced and experienced humanitarian professionals. We rely on surveys by telephone in a country where most don’t have a telephone and there is no network. As a result, what data, if it exists at all, is unreliable. And without data we don’t know how many people need assistance. We don’t know what kind of assistance they need, we don’t know if the assistance we have given has reached them, and we don’t know whether they will continue to need that assistance. Without reliable data, we don’t know anything.

This lack of knowledge is perpetuated by how we, as internationals, conduct our presence in Yemen. Yemen is ostensibly referred to by the UN security system as one of the most dangerous places in the Middle East. As a result, some of the most stringent security rules apply to us being in Yemen. Movements cannot take place unless in an armored vehicle. International aid workers are confined to comfortable compounds with apartments, restaurants, a gym, a pool, room service. These compounds are guarded by heavily armed guards, with sharpshooters on the walls. Any movement to the field is disincentivized through the imposition of bureaucratic hurdles and requirements for authorizations from not only authorities, but the [Saudi- and Emirati-led military] coalition and the authorization from the highest levels of the UN in Rome, Geneva and New York. Any mission in Yemen — urgent or not — takes at least a week, if not two, to be approved. This setup is considered one of the key impediments to the response in Yemen. As a result, most aid workers rarely move beyond the walls of their compounds in Sana’a and Aden – completely removed from those they are there to help. As one key informant put it: “Aid workers In Yemen live an entirely sanitized existence separated from the war, hunger, suffering, in fact separated from Yemen. Behind the walls of the UN compound in Sana’a with its restaurants, swimming pool and room service, air-conditioning and gyms, suffering, need and response has become an abstraction. It has lost a sense of urgency, purpose – perhaps even morality.” International aid workers are completely disconnected from the realities of Yemen. The best example to illustrate the extent of the problem can be described through Marib. Though now a daily headline in Yemen news, and now hosting a sizable cohort of aid workers, for almost four years, until 2019, the humanitarian response did not realize that there were almost a million displaced people in Marib city. It has taken another two years to establish any form of reasonable presence and response. There is something dreadfully wrong with this model.

Our lack of presence in the field is often blamed on the risk it would pose to us. But is this accurate? Representation of risk by UN security officials has often been proven to be false, debunked by research and analysis. INGOs move around Yemen without coming to harm. Yemenis go about their day-to-day lives without high numbers of casualties. And unlike Yemenis, we have armored vehicles. We have helmets and body armor, we carry medical equipment, we have security officers, and we can communicate by radio and satellite. We have aircraft that can pick us up if we are sick and hurt. And even then, we are barely willing to visit their country. When we do, I often struggle to imagine what it looks like to an ordinary Yemeni citizen. Lines of bright white air-conditioned vehicles, often if you are the UN, bookended by heavily armed technicals from one of the warring parties. A few minutes and a handful of questions at the most, if that, before disappearing rapidly in a cloud of dust back to a capital not to be seen again for months, years or perhaps ever again. It will come as no surprise that the opinion of ordinary Yemenis of us and the aid response is low.

The problem is that it does not have to be this way. The 2016-17 Battle of Mosul was described by the US army as the most intense urban combat since the Second World War. Despite this, and the real risk humanitarian aid workers faced to deliver aid in this setting, a shared commitment by aid workers and the UN security system, leadership and donors to deliver led to daily missions to the frontline for months with only 24 to 48 hours notice per mission. Trauma response was set up close to the frontlines. If we can do it in Iraq, and other places such as South Sudan and Afghanistan, we should be able to do this in Yemen.

The response often references access constraints as its main impediment. And this is true. There are genuine impediments to access in Yemen. In the north, the authorities have enforced an almost totalitarian system to control aid worker movements to which we have almost willingly succumbed and complied with barely a word said in resistance. Instead, we have used those who have created the restrictions to collect our data and implement activities for us, as a solution for the problem they created. This does not incentivize change. In the south, the greatest impediment to humanitarian access are humanitarians themselves and the security systems which are deployed to ostensibly keep us from harm.

Instead of pushing back against the authorities that have interfered and diverted assistance, or pushing the system to become more efficient and flexible, the humanitarian operation has instead taken a hard line against transparency and accountability — which are at the center of any functional humanitarian operation. Accountability from the donor to the taxpayer, humanitarian organizations to donors, and [to] those [the response] serves. The humanitarian system has always worked best when there has also been mutual accountability, where a joint presence of different components of the system — UN, NGOs, coordinators, donors and others — have rubbed shoulders while trying to deliver aid. When we are all actually present, it is difficult to pretend that food has been delivered when it hasn’t, or that health facilities are functioning when they are not. In most humanitarian operations around the world, this model has been severely eroded. In Yemen it barely exists. Each sector and actor increasingly operates in silos, avoiding questions about delivery and presence. The lack of data and the uncertainty over delivery has led to a hyper defensiveness amongst many actors, reducing transparency to an almost endangered state.

All this could be overcome by good leadership. Leadership in the humanitarian system is essential. It is needed to ensure that we are well-coordinated. That we are able to stand together and counter attempts to control us through the divide-and-rule approach. It is needed to ensure that redlines are set and unacceptable behavior is corrected – either by authorities, parties to the conflict, or by aid workers themselves. It is needed to protect staff, ensure adherence to humanitarian principles and to deliver the best response possible.

There is little evidence over the last six years of the humanitarian response of effective humanitarian leadership in Yemen at a national, subnational or international level. Some have tried, but have quickly found out that we are often our own worst enemy with internal competition and a lack of solidarity undermining even the most well-intentioned. As one humanitarian official commented: “The Houthis are bad enough, but we are just as damaging and as bad if not worse.” As several people have learned, trying to advocate for change, for a better response, even to just take a stand to defend humanitarian principles comes at a political cost. It is easier to look the other way.

So, where do we go from here? Some would say, if things are so bad then why fund the response in Yemen at all? Let me be clear, this is not a solution and is not what this report advocates for. This would be unconscionable. But we do have to do better. Yemen is the second-most funded response globally; with those resources, aid needs to be of a higher quality. It needs to be more principled. It needs to be appropriate, it needs to be faster, and it needs to be more accountable. We all know the root causes of the Yemen humanitarian crisis; they are not a secret. But then we should also stop pretending that handing out more food baskets or temporary shelter kits are a solution, or that this is what people want.

A wise person told me “there is no success without failure.” In Yemen we have been too afraid to admit to failure to be able to succeed. We are seven years into the response; they say late is better than never, but now is really the time. And there is an opportunity now. A formal review of the Yemen operation is ongoing and due to finish by the end of the year. It is an opportunity for the response to really evaluate itself and how to move forward, to do better. Continuing with the status quo cannot be an option. Yemen and Yemenis deserve better than that.

Sarah Vuylsteke worked as the Access Coordinator for the United Nations World Food Programme in Yemen from February to December in 2019. In this position, she traveled throughout the country, interacting with representatives from all sides of the conflict trying to facilitate aid delivery. Since 2015, she has worked for the United Nations and other international organizations in South Sudan, Yemen, the Central African Republic and Cameroon, and she is presently a field coordinator with Médecins Sans Frontières. Prior to 2015, Vuylsteke worked on human rights and conservation issues in Uganda, Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Commentaries

The Case for Mukalla as Yemen’s Capital

By Farea Al-Muslimi

In 2014, the Houthis took control of Sana’a. Five years later, President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi lost his temporary capital of Aden to the Southern Transitional Council. Yemen’s internationally recognized government is thus in need of a capital. The Cabinet, which spends most of its time in exile in Riyadh and other regional capitals, needs a presence inside Yemen if it hopes to reunite the country and remain legitimate. The fact that several ministers are based in Aden, the heartland of a rival political group, is awkward to say the least. There are few safe cities in Yemen that are well placed to serve as a new capital; Mukalla is the top option.

The capital of Hadramawt governorate in eastern Yemen, Mukalla is the country’s fourth-largest city. It is a coastal urban sprawl, with a low enough population density to accommodate growth, and has an active port with space to expand along the Arabian Sea, home to some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. Once the government is physically positioned in the city, Mukalla could become Yemen’s economic as well as political capital, revitalizing trade via land routes to Oman and Saudi Arabia and internationally via maritime routes to commercial partners in East Asia.

Mukalla, unlike other large Yemeni cities, does not suffer from water shortages. Hadramawt, which accounts for more than one-third of Yemen’s territory, borders Marib, Shabwa and Al-Mahra, and produces nearly two-thirds of Yemen’s oil and gas for export. The governorate also enjoys wide social diversity, a measure of economic diversity through its fishing industry and post-war tourism potential, and is home to some of Yemen’s best universities.

Sana’a, Aden and Hudaydah — the three largest Yemeni cities — are no longer viable options, and even an end to the war will not necessarily make them better suited. Sana’a, the official capital, is under the control of an armed group, and is likely to run out of water within a few decades due to the projected impact of climate change and years of improper drilling and inland water use. An affordable, sustainable way to supply water to the highland city and its 4 million inhabitants remains out of reach, making growth unsustainable.

Aden has been the internationally recognized government’s interim capital since 2015, but the past few years have demonstrated that the city is incapable of restoring its historical role as a center that embraces all Yemenis. Apparently, it cannot even embrace all southerners. There are a number of competing armed groups in Aden, and it is difficult to control the security situation. Aden’s infrastructure, hit hard by the war since 2015, has effectively collapsed and will take decades to repair, and the city suffers serious problems pertaining to garbage and sanitation. Aden is overcrowded and under-resourced. In addition, the plundering and neglect Aden suffered following Yemen’s 1994 civil war at the hands of northern elites, and Sana’a in particular, deflated its cosmopolitan spirit. It is under this pretext that armed warlords who have emerged since 2015 have turned Aden into a city feared by Yemenis. In recent years, residents with northern roots have been threatened and chased out.

Hudaydah, a port city along the Red Sea coast, has fewer security problems than Aden or Sana’a. It can provide its own water through desalination. However, Hudayah is currently under Houthi control, and has lost much of its earlier economic value and infrastructure. The commercial sector based around the port city was largely destroyed after 1990, as Aden became the main port post-unification. Hudaydah is now among the poorest cities in Yemen.

Choosing an Alternative

A few years ago, Taiz was suggested as a potential capital for geographical, cultural and historical reasons. However, in addition to the social and economic destruction it has suffered during the war, it is densely populated and its geography does not lend itself to expansion. The security situation is unstable, and similar to Aden in terms of the presence of irregular armed groups. Taiz struggles to provide sufficient water to its residents. This problem will worsen as the population increases, mostly due to poor infrastructure, which has been neglected for decades and only deteriorated more rapidly over the course of the war.

During the past few years, there has been talk of setting up a new capital in Marib or Shabwa governorates, with Marib city or Ataq replacing Sana’a. This is simply impractical, wishful thinking. Beyond the contested military situation there, the area of Marib city is barely equal to a single district of Mukalla. The larger governorate of Marib is desert. The infrastructure is underdeveloped within the city, now home to about 1 million people. Marib has been unable to provide services to an increasing number of internally displaced persons (IDPs), estimated by the International Organization for Migration at 1 million across the governorate, and existing schools and healthcare centers are few in number and not properly equipped. Shabwa is in a similar situation, even though it is home to the most economically significant facility in Yemen, the refinery in Balhaf. Shabwa’s oil and gas wealth are not enough, however, to make the governorate suitable for hosting a national capital. Shabwa’s central city, Ataq, has poor infrastructure, and, like Marib, it is in the middle of the desert, home to strong tribal groups that may chafe at urban expansion.

Enter Mukalla

Despite its political and economic advantages, comparatively good infrastructure, and elegance and distinction as a city, Mukalla has drawn little international attention except, perhaps, from Saudi Arabia. Many Hadrami expatriates have acquired Saudi nationality since the formation of the modern kingdom. Over the years, they have developed strong financial and business networks in Saudi Arabia, while maintaining a strong connection to their local community in Hadramawt.

Perhaps the most important reason for establishing Mukalla as the new capital, and keeping it there after the war, is that it would derail the plans of those parties that want to fragment Yemen, such as the Houthis in the north or the Southern Transitional Council in the south. Furthermore, it would help deter dominant regional powers across Yemen from establishing central control. Restraining both fragmentation and centralization from Mukalla could redefine Yemenis’ relationships with each other, and help address and heal the grievances of the country’s citizens.

Farea Al-Muslimi is the chairman and co-founder of the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

Has Riyadh Woken Up From Its Al-Mahra Pipe Dream?

Commentary by Yehya Abuzaid

Since 2017, many residents of Al-Mahra, Yemen’s easternmost governorate, have had a growing anxiety regarding their Saudi neighbors to the north. What began as a trickle of Saudi troops[8] into the area quickly transformed into what appeared to be a fully fledged campaign for control of the governorate, including its border with Oman to the east. By 2019, the Saudis had established more than 20 military bases and outposts across Al-Mahra, a governorate with no more than 300,000 inhabitants.[9] This deployment has fueled speculation from American[10] and Yemeni experts,[11] as well as Mahri locals,[12] that the reason for the Saudi presence was to secure Al-Mahra for the construction of a pipeline to carry Saudi crude oil to the Arabian Sea. The pipeline rumor has increased local resistance and inflamed tensions in the governorate between those who supported and opposed the Saudi presence.[13]

Then, at the beginning of November 2021, Saudi troops suddenly began withdrawing from positions in the governorate.[14] This was quickly followed by Omani Minister of Economy Said bin Mohammed al-Saqri calling for the revival of a decades-old proposal to construct a pipeline that would transport Saudi oil through Oman to the Arabian Sea.[15] While these events are ostensibly unconnected, many observers have been quick to connect the dots and see Saudi Arabia reorienting its pipeline dream from Al-Mahra to the east.

Suspicions over Saudi Arabia’s intentions in Yemen’s east are nothing new. Some experts argue that Saudi Arabia has long desired access to the Arabian Sea via its neighbor to the south.[16] The strategic impetus is clear: It would end Saudi Arabia’s dependence on passage through the Strait of Hormuz, through which the majority of its oil exports pass and which might easily be threatened by Iran, the kingdom’s archrival across the Persian Gulf. This concern was evident during Saudi-Yemeni negotiations for an oil pipeline in the 1990s.[17] The negotiations eventually broke down over then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s fears of Saudi Arabia’s growing influence in the country.[18]

But Saudi interest in the pipeline did not end with the failed negotiations. According to a leaked American diplomatic cable from 2008, the Saudis remained keen to secure territory and build a pipeline by buying the loyalty of local leaders across the country.[19] Many continued to view the desire for an oil pipeline in Yemen as a key dimension of the Saudi-Yemeni relationship.

Suspicion regarding a pipeline through Yemen intensified when Saudi Arabia began entrenching itself in Al-Mahra in 2017. Aside from the many military installations Riyadh built in the governorate, Saudi Arabia recruited thousands of Mahris, putting them on its payroll in an apparent attempt to pacify antagonistic tribesmen and create its own irregular military force.[20] Additionally, the transfer of Mahri tribes residing in Saudi Arabia to Al-Mahra since 2017 created a base of support in the area.[21] Saudi construction firms have attempted to build infrastructure that many in the governorate thought was a precursor for a pipeline, leading to clashes between Mahri tribes and Saudi engineering crews.[22] Saudi forces also secured Nishtun port,[23] raising local suspicions that it was the intended site for an oil export terminal.

These suspicions were further fueled in 2018, by a memo leaked to local media in which a Saudi construction company, Huta Marine, thanked the Saudi ambassador to Yemen for commissioning a feasibility study for the construction of an oil port.[24] While neither Nishtun nor Al-Mahra were explicitly mentioned in the memo, the control of most of Yemen’s other viable ports by Houthi fighters and UAE-backed local forces was enough to drive speculation that the memo referred to Nishtun. The Middle East Monitor went so far as to use the memo and local fears to claim in a headline: “Saudi Arabia prepares to extend oil pipeline through Yemen to Arabian Sea.”[25]

While speculation regarding Riyadh’s pipeline ambitions has seemed plausible, it also merits some healthy skepticism. Saudi deployments and other tactics, such as transferring loyalist tribesmen, could represent a desire to counter Oman’s influence in Al-Mahra. It is no secret that there were tensions in the Saudi-Omani relationship, which only worsened once the Yemen war began. The Omanis, for their part, have leveraged various factors – including their native Mahri population, a targeted policy of granting residents of Al-Mahra Omani citizenship,[26] aid donations,[27] and maintaining close ties with Mahri political leaders, such as the prominent anti-Saudi figure Ali al-Hurayzi[28] – to push back against Saudi influence in the area. Publicly, the Saudis claim their troop deployments in Al-Mahra are focused on combating Houthi arms smuggling,[29] and indeed, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen have accused the Omanis of facilitating Houthi smuggling efforts through the governorate.[30]

The theory that Riyadh was preparing to establish a pipeline in Al-Mahra seems implausible in light of Yemen’s entrenched political instability. Saudi Arabia’s ability to maneuver politically, economically and militarily in Yemen is significantly influenced by events outside of Al-Mahra, such as conflict with Houthi forces, tensions with Iran and Oman, and the reliability of the United States as an ally. Then there is the threat within the governorate from restive tribes who have a strong desire for autonomy, and even independence. If the Saudis were being practical about a potential oil pipeline, they would have to consider their ability, or lack of, to protect this immovable, multi-billion dollar asset.[31] Even before the uprising of 2011, a report by the Gulf Research Center, a Saudi think tank, concluded that Yemen was too volatile to consider a project to transport oil via a pipeline.[32] The Omani minister’s renewed call for a pipeline to transfer Saudi oil, coupled with an overall easing of tensions between Oman and Saudi Arabia since the ascension of Sultan Haithem, presents the Saudis with a more realistic, and less risky, prospect to the east.

The theory that Riyadh maintained a desire for a pipeline through Al-Mahra during the ongoing conflict was attractive to its supporters. Were Al-Mahra to be transformed from a peripheral, forgotten corner of Yemen into a key transit route for Saudi oil, it would have marked one of the most significant geopolitical shifts in the Yemen conflict. It would recast perceptions of the notoriously opaque Saudi strategic planning and redefined the war as one of conquest rather than regional rivalry and poor decision-making. Now, with Saudi-Omani relations appearing to have turned over a new leaf, we may never know what the kingdom’s ambitions were.

With warming relations between Riyadh and Muscat, Mahris might breathe a sigh of relief now that a significant threat to the relative stability they have enjoyed during the war has receded. This inclination may be premature. However Saudi intentions in Al-Mahra evolve, the Saudi policy of building tribal and military influence in the governorate puts them in a strong position to try and enforce their policy preferences. If the Yemeni war ends with the country’s fragmentation, whether officially or in practice, Riyadh could still pursue territorial ambitions in Al-Mahra to salvage something from their quagmire.

Yehya Abuzaid is a research fellow at UC Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute and a member of the Sana’a Center US team. He primarily focuses on Middle East geopolitics, conflict resolution, and climate resilience.

An Unneighborly Rapport: How Yemeni-Saudi Relations Went Astray

By Abdulghani Al-Iryani

The Taif Treaty between North Yemen and Saudi Arabia ended the 1934 war between the two states and led to the Saudi annexation of the disputed provinces of Najran, Jizan and Asir. The treaty stipulated Saudi control over the disputed provinces for a period of 40 years. It also granted the right of the citizens of each country to live and work in the other country. That was followed by 30 years of peace that allowed the development of strong economic ties and facilitated the migration of hundreds of thousands of Yemeni workers to the kingdom.

The relations soured after the September 1962 Republican Revolution against Imam Mohammed al-Badr, who fled to Saudi Arabia. The revolutionaries invited Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt, Saudi Arabia’s main competitor in the region, to send troops to support the nascent republic. Shortly after, Vice President Abdul-Rahman al-Baydani, who was forced upon the revolutionaries by the Egyptians, threatened to bomb the palaces of Riyadh. That ushered in a major Saudi intervention in support of the royalist forces that fought to restore the imam to power in Sana’a. Egyptian intervention stopped after an agreement between President Nasser and King Faisal bin Abdulaziz al-Saud following Egypt’s defeat in the Six-Day War of 1967, but the Saudis, despite their agreement with Egypt, kept financing the royalists until 1970. When it became clear that the royalists could not win, Saudi Arabia cut the funding for their war effort and brokered a peace agreement between them and the republicans that granted the royalists a nominal share of political power in the republican system. A new page of relations between North Yemen (the Yemen Arab Republic) and Saudi Arabia started, lasting only a few years, characterized by hegemonic Saudi influence over Yemen and its persistent attempts to finalize the boundary line of 1934. In April 1973, Riyadh managed to get the Yemeni Prime Minister, Abdallah al-Hajri, to renew the Taif Treaty — a move that was struck down by the governing Presidential Council, prompting Saudi Arabia to sponsor the overthrow of the civilian government and replace it with a military council.

The leader of the Military Command Council, Ibrahim Al-Hamdi, proved equally resistant to Saudi hegemony. He was assassinated in October 1977 in a plot widely believed to have been sponsored by Saudi Arabia. The commander who killed Al-Hamdi and succeeded him as president, Ahmed al-Ghashmi, was in turn assassinated eight months later by a suicide bomber sent by the leader of South Yemen, Salim Rubai Ali, leading to Ali Abdullah Saleh assuming power in the North.

The wily Saleh skillfully survived the ups and downs of relations with Saudi Arabia despite his resistance to renew the Taif Treaty. He often said that no president of one part of Yemen can finalize the boundary line with the Saudis, as the other part of Yemen will consider that a sell-out. From 1978 until unification in 1990, Saleh was targeted by several assassination attempts that he attributed to Saudi Arabia.

Unification of the two parts of Yemen, a national objective that had been pursued by northern and southern Yemeni leaders for decades, took place in 1990. Saleh became the president; the leader of the South, Ali Salem al-Beidh, became vice president. Unification was opposed by Riyadh, but was supported by Saddam Hussein of Iraq and Moammar Gadhafi of Libya, both of whom were hostile to Saudi Arabia. Relations between the newly unified republic and Saudi Arabia would soon sour even more.

As an accident of history, Saddam invaded Kuwait a few months after Yemeni unification. Saleh chose the side of Saddam, against the protests of most senior Yemeni officials including his vice president, Al-Beidh, whom Salah quickly marginalized to become the sole decider of Yemen’s foreign policy. To Yemen’s misfortune, it was the only Arab member of the UN Security Council at the time, and Saleh instructed his representative to abstain from the vote that authorized the use of military force to liberate Kuwait. Saleh also instructed his government to organize massive demonstrations of solidarity with Iraq. Students were dismissed from schools and civil servants from work and all were instructed to join. Yemen’s actions triggered a massive backlash by Saudi Arabia (and some other Gulf states) that included abolishing the special privilege given to Yemeni migrant workers to work in the kingdom without a sponsor and the summary expulsion of approximately 1 million Yemeni migrant workers who could not liquidate their businesses or sell their assets.

Despite the cooling of relations of 1990-91, Saudi Arabia and Yemen resumed communication on two key issues: finalizing the border; and a Saudi proposal to build a pipeline through eastern Yemen to export Saudi oil, skirting the chokehold of the Strait of Hormuz. Some progress was achieved on both topics. Saleh agreed to start talking about the border and agreed in principle to the pipeline proposal. A point of disagreement was the security arrangements for the pipeline. Saudi Arabia insisted on joint security arrangements and Saleh, citing sovereignty, insisted on Yemen handling all security arrangements.

In the meantime, Saleh’s marginalization of his vice president and a wave of assassinations that claimed the lives of more than 150 Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) leaders led to tension that culminated in the 1994 war between YSP forces and northern forces, supported by a dozen southern brigades that had fled to the North after the 1986 civil war in Aden. Six months before the war, when it had become clear that Saudi Arabia was supporting the YSP and bankrolling its weapons deals, including Scud-B missiles from North Korea and MiG-29 bombers from eastern Europe, Saleh informed Riyadh that he was agreeable to joint security arrangements for the pipeline. The Saudi response was that it would accept nothing less than full sovereignty over the pipeline corridor.

Soon after the war, a memorandum of understanding was signed by the two states that initiated the process of demarcating the boundary line. Six years later, the process ended with the signing of the 2000 Treaty of Jeddah permanently demarcating the border between the two states.

With its main security concern, the boundary line, satisfactorily resolved, Saudi Arabia showed a willingness to turn a new page. Saudi financial support for Yemen, greater work opportunities for Yemeni migrants, and plans for developing the border communities and funding Yemeni Border Guards were clear indicators. However, Saleh did not reciprocate. Weapons used by Al-Qaeda in terrorist attacks in Saudi Arabia were traced back to Saleh and his erstwhile partner, General Ali Mohsen. Mutual confidence was again shattered. The pipeline proposal, which two members of the Yemen Technical Committee for Border Affairs involved in the discussions said continued at the technical level until 2003, seemed to have been put on hold due to the Houthi rebellion of 2004. This emerging shared security concern meant Saudi support for Yemen continued, albeit plans to integrate Yemen into the regional economy through the Gulf Cooperation Council waned.

As the Sa’ada wars raged, Saudi Arabia focused on managing the immediate threat of growing Iranian influence in Yemen. Yemeni-Saudi relations at the leadership level improved significantly, with Saleh receiving frequent infusions of cash from Saudi Arabia. The Sa’ada wars, which Saleh used to degrade the military forces of his main competitor, General Ali Mohsen, also turned the small Houthi militia into a significant military force. Saudi Arabia continued to support Saleh, even as major protests called for his overthrow during the 2011 Youth Revolution. When it became clear that Saleh could no longer hold on to power, Saudi Arabia supported a peaceful transfer of power and sponsored the political agreement to achieve it.

With Saudi Arabia now negotiating a pipeline through Oman, it is clear that Yemen in Saudi eyes is, first and foremost, a security concern. Yemen has posed a real or imagined threat to the kingdom throughout the past century. This has been amply demonstrated in the current Yemen conflict. It is also clear that, in Yemeni eyes, Saudi Arabia is a hegemonic power that has cast its gaze on part of Yemen’s territory. Stability in this part of Arabia will not be restored until this main concern is dealt with.

Abdulghani Al-Iryani is a senior researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies where he focuses on the peace process, conflict analysis and transformations of the Yemeni state.

In Endless Pursuit of Refuge

By Manal Ghanem

The last major stronghold of the internationally recognized government in northern Yemen, Marib governorate lies 173 kilometers to the northeast of the country’s Houthi-controlled capital, Sana’a. Renewed fighting began in Marib in July 2020 but escalated significantly in September and October 2021.

The upsurge in the scale and intensity of the fighting is a result of a resurgent campaign by the armed Houthi movement, made possible after the group consolidated control over southeastern Marib, neighboring Bayda’ governorate, and the three districts of Shabwah governorate that border Marib – Bayhan, Ain and Usaylaan. Control of these areas enabled Houthi forces to secure a supply route from Sana’a to Marib, and thousands of Houthi fighters have since descended onto the active frontlines south of Marib, edging their way toward Marib city as the southern districts of the governorate have fallen.

As the internationally recognized government steadily loses its grip on the governorate, the recent fighting has become increasingly devastating for the civilian population. In 2004, before the onset of the current conflict, the population of the governorate stood at 238,522.[33] But between 2014 and 2021, some two to three million internally displaced people (IDPs) have spent time in Marib.[34] With the possibility of the siege or seizure of Marib city by Houthi forces, thousands of IDPs are now preparing to flee for a second or third time.

A History of Displacement

After Houthi forces consolidated their control over Sana’a in 2015, a wave of displacement was seen throughout the country. People fled areas with active frontlines in search of safety and stability, settling in comparatively calmer districts. Marib governorate became a key destination for IDPs, as it was relatively isolated from the conflict.[35] Many northerners, both families and business owners, who fled Houthi rule but felt unwelcome in southern Yemen, due to historical animosities between two regions, also turned to Marib. The city also benefited from its proximity to Yemen’s northern border with Saudi Arabia and harmonious relations between its respective tribes. Thousands of highly qualified Yemenis fled conflict zones and settled in the city, bringing with them their professional expertise and directly contributing to the city’s transformation. By 2018, new developments were spreading, investment and real estate prices had increased, and businesses began to flourish.

The governorate also benefited from the decision in 2015 to cut ties with the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Sana’a, allowing the governorate maintain control over local revenues from Marib’s extensive oil and gas resources. Marib Governor Sultan Aradah later forged an agreement with the internationally recognized government that allowed the governorate to keep 20 percent of local oil and gas revenues. In mid-2021, Marib’s crude oil exports were estimated to be worth US$19.5 million per month.[36]

Prior to the escalation of fighting in September 2021, Marib city hosted 602,000 IDPs, Al-Jubah district hosted 9,300 IDPs, Marib al-Wadi hosted 101,000 IDPs and Al-Abdiyah district hosted 16,800 IDPs.[37] Among these IDPs, 80 percent were women and children, whom the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) noted suffer disproportionately from the overcrowding and lack of basic services in overpopulated camps.[38] In addition, 4,000 IDPs are migrants who were stranded in the governorate while attempting to cross into Saudi Arabia. Most struggle to find jobs and access basic services, and face various forms of abuse.[39]

According to UNHCR,[40] roughly 172,000 individuals were forcibly relocated in Yemen in 2020, which contributed to Yemen having the world’s fourth largest number of IDPs after Syria, Colombia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. One in every four displaced Yemeni families is headed by a woman or girl; 20 percent of them are under 18 years of age. In 2021, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimated there were some 1.6 million children among the IDPs in Hudaydah and Marib governorates.[41]

The Long Route to Safety

The escalation of conflict in Marib in September forced thousands more civilians to seek safety away from Marib’s active frontlines and led to an alarming rise in the number of displaced. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) says Marib now has more than 125 IDP camps, nineteen more than it had in 2020.[42] Around 70 percent of the IDPs are in Marib city, including the largest camp, Al-Jufainah, which now holds up to 10,000 people.[43] The number of IDPs in the city has also risen due to recent advances by Houthi fighters in neighboring Shabwa governorate. As the wave of displacement increases, an enormous and growing burden is placed on available resources and aid workers.[44]

More than 10,000 people were displaced in Marib governorate in September, the highest recorded figure in any month during 2021.[45] Since, the humanitarian situation has worsened after fighting in the southern districts of Al-Abdiyah, Al-Jubah and Jabal Murad. Accurate estimates are difficult to obtain due to the difficulties of communication in contested areas, but the IOM says more than 4,700 people[46] have fled the conflict toward Al-Jubah and Marib al-Wadi districts and Marib city. This brings the total number of people seeking refuge in Marib city to around 170,000 since January 2020, many of whom have been displaced multiple times previously.[47] Some have moved into established camps, exacerbating overcrowded conditions and a lack of resources, but the majority are still without proper shelter, seeking protection in such places as abandoned buildings, caves and under bridges.[48]

Following their gains in Al-Bayda and Shabwa, Houthi fighters besieged Al-Abdiyah district in the south of Marib governorate on September 23, preventing civilians from traveling in and out and hindering humanitarian aid workers from accessing the area. After three days and tribal mediation, residents were allowed to purchase necessary goods and services from the neighboring Mahiliyah district.[49] After Houthi forces consolidated their control of Al-Abdiyah, hundreds of families then fled, heading towards Marib city.

Approximately 40,000 people – almost 70 percent – of the IDPs in southern Marib governorate this year have been forced to flee since September. According to the Executive Unit for IDP Camps in Marib,[50] a total of 8,088 families, or approximately 54,502 people, were displaced inside the governorate as of the end of October. Around 287 families were reportedly displaced from one location to another within Al-Jubah and Rahabah districts. Marib city hosts around 5,000 displaced families, while Marib al-Wadi hosts 2,799 families from the southern districts in the governorate and Ain, Bayhan and Usaylaan districts in Shabwa. Currently, thousands of civilians are under direct threat from fighting or targeted missile attacks. On October 31, two Houthi ballistic missiles hit the Dar al-Hadith Salafi religious center in Al-Amoud village in Al-Jubah district.[51] The facility, which includes a school and mosque, was hosting several Salafi families displaced from Dammaj in Sa’ada governorate, following battles with Houthi forces there between 2011 and 2014. At least 26 civilians were killed and many more wounded in the missile strikes.[52] Estimates indicate that around 500,000 people are likely to be displaced if Marib city and the Marib al-Wadi district are captured by Houthis troops.[53]

Looking Ahead

Yemen’s humanitarian crisis has deepened as the conflict has continued to rage. The intensity of the fighting has steadily risen since 2020. Flooding and the Covid-19 pandemic have aggravated health and safety conditions in displacement camps. Internal displacement affects more than the security and livelihoods of the people, in that it also directly impacts their health, education and chance to lead a normal life in the future. Because of the increasing trend of repeated displacement, IDPs are at a severe disadvantage. Research has shown that prolonged displacement increases the risk of mental disorders.[54] As the war continues and clashes worsen, Yemenis will continue to seek shelter and safety. IDPs are a forgotten consequence of the violent power struggle the country is experiencing. The death toll from war is tragic in itself, but the fate of the displaced must not pass unnoticed.

Manal Ghanem is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies where her work focuses on cultural and technical research.

In Focus

Development Assistance in Yemen: A Cautionary Tale from Al-Mahra

Commentary by Ameen Mohammed Salmeen ben Asem

Even before the current conflict, Yemen’s development needs were vast.[55] The escalation of the war in 2015 worsened many of the country’s pre-existing systemic and infrastructural deficiencies. This makes Yemen a prime target for international development assistance, both now and especially in any post-conflict scenario. However, good intentions and money are insufficient to ensure that development projects, even those that are badly needed, will be accepted and successful in the communities they are meant to benefit.

The following is a cautionary tale from Al-Ghaydah, the capital city of Al-Mahra, Yemen’s easternmost governorate. Based on interviews with local officials, residents and private sector actors, it relates how a project to install a sewage system and treatment plant in the city using foreign funding was initiated before faltering and ultimately aborted. While the specific dynamics of development assistance will vary by region and initiative, the general lesson is widely applicable: development projects that do not curry meaningful local engagement and buy-in will likely face resistance and fail.

Al-Ghaydah’s Wastewater Challenges

In 2004, the last year a census was conducted in Yemen, the population of Al-Mahra was estimated at just under 90,000 and projected to grow 4.5 percent annually.[56] The majority of the governorate’s residents, then and now, live in and around the capital. Over time, Al-Ghaydah’s expanding population has brought into increasing focus the fact that the city does not have an integrated means of disposing of human wastewater. At best, buildings in the city have their own respective septic systems buried in the ground, at worst, wastewater is disposed of in open cesspits. Services to maintain both are limited.[57]

The increasing volume of wastewater pumped into the ground, coupled with periodic heavy rains and flooding, has regularly caused wastewater to overflow in residential and commercial areas of the city, polluting clean water sources and creating a public health hazard as well as a deeply unpleasant experience for local residents.[58] During the ongoing conflict, Al-Mahra’s relative stability and location far from the frontlines has led to a rapid population influx to the governorate from other parts of Yemen, estimated in the hundreds of thousands.[59] Many families and businesses are establishing themselves in and around Al-Ghaydah, compounding the city’s wastewater woes.

An Attempt to Build a Sewage System and Treatment Plant

In 2006, at a London donor conference, Oman pledged US$100 million to development projects in Yemen via the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development and the Yemeni Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation.[60] The grant money was to be released in stages and focused specifically on economically developing the border region between the two countries.[61] In 2014, through this grant, a number of projects were set to kick off in Al-Mahra, including a sanitation project for Al-Ghaydah.[62] This was undertaken after much follow-up by the late former governor of the governorate, Ali Mohammed Khawdam.[63] On February 23, 2014, a contract was signed between the Urban Cities Project of the Ministry of Water and Environment and the Sana’a-based Abdulaziz Altam Trading and Contracting Corporation.[64] The signing was also attended by the Egyptian firm consulting on the project, Arab Consulting Engineers (ACE) Moharram Bakhoum.[65]

The project was to include a sewage treatment plant and a system of sewer pipes covering 80 kilometers.[66] The pipes would traverse several neighborhoods of the city – in particular the areas of Bin Hijleh, Bin Ghouna, Kalashat and Al-Nahda – though it was by no means intended to serve the whole population.

The project broke ground May 26, 2014,[67] and the Abdulaziz Altam Corporation started implementation based on an assessment and project plan that had been prepared by the Jordanian consulting firm Sajdi Consulting Engineering Center.[68] The work included digging, laying and connecting the pipes, as well as installing manholes and small inspection rooms at set distances.[69] But operations ceased in June 2015. Abdulaziz Altam Corporation requested that the contract be voided due to threats against the company by local contractors and protests over the planned location of the sewage treatment plant.[70] In May 2016, the Arab fund accepted the request to void the contract, and the project was liquidated.[71]

Local Grievances Lead to Resistance

In both the design and attempted implementation of the sanitation project there was a distinct lack of consultation and engagement with the communities in which the project was to take place. For instance, the plans drawn up by the Jordanian consulting firm called for the treatment plant to be situated roughly 700 meters from Shahouh, a residential district on the eastern edge of Al-Ghaydah home to about 50 families. On most days, the winds in Al-Mahra come from the direction of the sea, which would have pushed smells from the plant’s uncovered sewage treatment basins into Shahouh. The residents of the area protested and demanded that the plant be moved to a more suitable area, and threatened to continue to fight against local authorities over the project’s implementation.[72]