The Sana’a Center Editorial

Diplomacy May Pause the Fighting; It Cannot Impose the Peace

International stakeholders to the Yemen conflict have pursued a rush of diplomatic initiatives in recent months that are unprecedented in the war to date. Consensus among regional and international actors to achieve a cease-fire appears closer now than ever before – with the right efforts made to gain buy-in, this could help create a framework for talks among Yemeni parties focused on ending the ongoing war. Simultaneously, events in Yemen itself, specifically the ongoing battle for Marib, threaten to derail prospects for peace for years to come should the armed Houthi movement seize this northern stronghold of the internationally recognized Yemeni government.

Underlying the international moves of late have been the shifting dynamics between Washington, Riyadh and Tehran. Washington’s political and military support for the Saudi-led military coalition intervention in Yemen – during both the Obama and Trump administrations – has been instrumental in sustaining the protracted conflict, now in its seventh year. Also instrumental has been Iranian support for the armed Houthi movement – politically, strategically and militarily, with the latter in direct violation of UN arms sanctions.

It was largely Saudi fears that Iran would establish a foothold in Yemen through the Houthis that drove Riyadh to launch its military intervention in Yemen in 2015. At the time, the US backed the intervention in large part to limit Saudi opposition to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) Washington was then finalizing with Tehran to limit the latter’s nuclear program. While in the first years of the Yemen conflict the Houthi forces benefited domestically from their alliance with former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, as the conflict escalated the group also sought more outside assistance from the sole sources willing to offer it – Tehran and its regional proxy forces. Over the subsequent years, Iranian assistance has helped Houthi forces attain increasing battlefield sophistication, gain the upper hand on Yemeni rivals, impose increasingly higher costs on Saudi Arabia and establish its unrivalled dominance across most of northern Yemen. For Tehran, supporting the Houthis began as a relatively low-cost, high-impact avenue by which to harass its arch-rival Saudi Arabia. As the Houthis’ position on the ground has strengthened, so too have Iranian interests and investments in the group.

It has become among the war’s tragic ironies that today, thanks to Saudi Arabia, the Houthis and Iran have never been closer. Meanwhile, Riyadh has become trapped in a military quagmire and is paying dearly in riches, reputation and clout. It has been clear for some time that the kingdom wants out of Yemen. And Washington, after the Trump administration tore up the Iran nuclear deal, has been left paying the cost of the deal – being a primary backer of an unwinnable war that has unleashed a humanitarian catastrophe – without any of the payoffs the Obama administration had sought.

Among the factors driving the new international dynamics regarding the conflict is the about-turn in the US approach since the Biden administration took office. The new US president has explicitly called for an end to the Yemen war, appointed an envoy to lead this diplomatic charge and halted some US arms sales to Saudi Arabia – importantly, the latter comes after billions upon billions of dollars worth of previous US arms sales have left the kingdom already armed to the teeth. Also important to note is that neither the US, nor any of the other five permanent members of the UN Security Council, have yet brought forward a new framework for negotiations beyond Resolution 2216, which the US and United Kingdom pushed through the security council in 2015 to give international legitimacy to the Saudi-led intervention.

The fate of the Yemen conflict now appears to be increasingly linked with larger efforts toward regional deescalation. The US, Iran and other world powers met in Vienna in March and April for talks on bringing Washington and Tehran back into compliance with the JCPOA. In recent months, Oman has been hosting a flurry of diplomatic meetings, with representatives of the United States, Saudi Arabia, the armed Houthi movement, Iran, the United Nations and others brushing shoulders in Muscat with increased frequency. In April, Baghdad then played host to a discreet meeting between Saudi and Iranian security officials, at which they discussed regional flashpoints between them, including Yemen. This was followed by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman giving a television interview in which he said the kingdom sought to build a “positive relationship” with Iran. Officials from Oman, the UN, the US and others have also been gathering for talks in Riyadh in recent weeks. For Saudi Arabia, however, a precondition for any agreement to end the Yemen conflict is security along its southern border, particularly in the face of regular Houthi drone and missile attacks into the kingdom.

In any conceivable future, the Houthis’ ties with Tehran, with whom the group has exchanged ambassadors, will remain prized – which should worry every stakeholder who cares about peace in Yemen. As international dynamics have been realigning toward peace, Houthi forces on the ground in Yemen have continued to press an assault on Marib city. For the Yemeni government to maintain relevance in the country and in any future peace negotiations, it must not lose this stronghold. The dynamics at play among the various stakeholders inside and outside Yemen would change dramatically if the city falls into Houthi hands, with the prospects for a UN-mediated peace likely to vanish and not return for years. With Marib, the Houthis would consolidate control over northern Yemen, as well as oil and gas fields that could offer an economic base for a new Houthi state; the group’s leaders would feel little compulsion to make concessions. Rather, Houthi demands for ending their military conquest would likely grow astronomically and entail terms that neither Saudi Arabia nor any other Yemenis could stomach.

Even if the emerging international and domestic dynamics end up bringing the parties to the table, peace will continue to face many challenges. A durable cease-fire and post-conflict environment will depend on finding a stable balance among the domestic forces in Yemen, with regional and international actors providing mechanisms to guarantee the arrangement. The danger here, however, would be if international priorities came to dominate those of Yemenis; we have already seen how the results of such played out in Yemen’s post-2011 failed “transition process” – dubbed the Gulf Cooperation Council Initiative, aptly reflecting its priorities – that helped bring on current conflict. As well, hardliners within the Houthi movement will almost certainly push to keep an inordinate share of power during negotiations – which would be unacceptable to any other portion of Yemeni society – and seek to usurp any agreement the group’s more moderate and pragmatic negotiators might make. Similarly, divisions within the anti-Houthi coalition could easily undermine its side in the negotiations.

It would be dangerous for international actors to push for an immediate, comprehensive cease-fire prior to the basic prerequisites of a post-conflict state being agreed. Such an arrangement would create an incentive for armed groups that are currently reaping handsome profits from the populations under their control to maintain the status quo by obstructing a power-sharing deal. Rather than giving Yemen the best chance to find a path toward sustainable peace, a more likely scenario would be a relapse into war and a slow and final disintegration of the Yemeni state into warlord-run fiefdoms. Instead, a conditional, limited cease-fire, focused on freezing frontlines in place, should be sought to allow the opportunity for negotiations on the basic prerequisites of a post-conflict arrangement. This should entail identifying basic end goals for political power sharing, social equality and revenue sharing under a unified Republic of Yemen.

Contents

- Eye on Yemen

- The Political Arena

-

State of the War

- Government Offensive Pressures Houthis in Taiz

- Intense Fighting but Few Advances in Marib

- Fighting Escalates in Hudaydah; New Government Offensive in Hajjah

- Houthis Pepper Saudi Arabia with Cross-Border Attacks

- Escalation in AQAP-linked Attacks in Abyan

- Government-STC clashes in Abyan Threaten Stability in the South

-

Economic Developments

- Update on Local Exchange Rates

- Government Presents Fuel Data in Defense of Reduced Fuel Import Activity at Hudaydah

- Saudi Arabia Pledges US$422 million Fuel Grant for Govt Areas

- Panel of Experts Revise Analysis of CBY-Aden

- Shabwa Local Authority Cancels Agreement for Qana Port Development

- Houthis Temporarily Open YPC Fuel Stations in Sana’a

- Sana’a Chamber of Commerce and Industry Denounce Houthi Zakat Authority

-

Reflections on the 2011 Yemeni Uprising a Decade On:

- The Day I Wore a Revolution – by Bilqis Lahabi

- The Other Side of the Wall – by Salah Ali Salah

- The Yemen Uprisings: The View from Turtle Bay – by Casey Coombs

- How the Fractious Elite Hijacked the Yemeni Uprising – by Abdulghani al-Iryani

- A Decade of Shattered and Betrayed Dreams – by Mohammed Al-Qadhi

- Dignity is in Aspirations, Not in a Wall – by Bilqis Lahabi

- The Kingpin of Sana’a: A Profile of Ahmed Hamid – by Gregory Johnsen and Sana’a Center Staff

- A View From the Frontlines: Taiz – by Khaled Farouq

- ‘The Battle of All Yemenis Against the Houthi Coup’ – A Q&A with Tareq Saleh

- The Corruption is Real: UN Panel Should Not Have Retracted Embezzlement Accusations – by Khaled Monassar

- Toward a Wise US Policy in Yemen – by Alexandra Stark

- Socotra Faces COVID-19’s Rising Tide Unprepared – by Quentin Müller, Socotra

March & April at a Glance

Eye on Yemen

Intensified Seasonal Flooding

Torrential rains struck much of Yemen in mid-April and lasted through the end of the month, causing widespread flooding that destroyed homes and infrastructure. Spring typically heralds the beginning of the rainy season in Yemen, however extreme weather events have become more frequent and more intense in recent decades, with their impacts magnified by the country’s already weak infrastructure and urban planning.

As of the beginning of May, deaths and injuries were reported along with the displacement of more than 20,000 people, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, which reported large-scale damage in Aden, Abyan, Al-Dhalea, Lahj, Hadramawt, Marib and Taiz governorates. In Tarim district, Hadramawt governorate, four people were reported killed and 167 homes destroyed as of May 2. Photographer Mohammed Haian documented the scene there the following day for the Sana’a Center.

The Political Arena

By Casey Coombs

Developments in Government-Controlled Territory

Local Authorities Call for Canceling Stockholm Agreement

March 1: In a letter, former heads of local councils in eight Houthi-controlled governorates – Amanat al-Asimah, Ibb, Hudaydah, Al-Mahwit, Dhamar, Raymah, Sa’ada and Amran – called on President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi to cancel the Stockholm Agreement. The letter also requested that the internationally recognized government make regular payments of military salaries and reactivate all battlefronts to implement UN Security Council resolution 2216 by force.

STC President Tells The Guardian, CNN of Secessionist Plans

March 1: In an interview published in the UK-based newspaper The Guardian, Southern Transitional Council (STC) President Aiderous al-Zubaidi said the secessionist group seeks a referendum for an independent south Yemen despite the formation of a power-sharing cabinet with the internationally recognized government in December, as part of the Riyadh Agreement. The interview was a continuation of the STC leader’s high-profile appearances in international media since the start of the year. Al-Zubaidi also told The Guardian that a Houthi takeover of the government stronghold of Marib could position the STC for direct talks with the Sana’a-based Houthi authorities: “It could lead to a situation where the STC are largely in control of the South and the Houthis control most of the North. In that case, it would make sense to have direct talks between the parties that are in control,” he said.

Al-Zubaidi, however, seemed to walk back that statement in a March 15 interview with CNN International in Abu Dhabi, when he said that such negotiations would only take place under the umbrella of the UN and international organizations, adding that coexistence with the Houthis is not possible. In January and February, Al-Zubaidi spoke with UAE-based SkyNews Arabia and Russia Today, during which he reiterated the STC’s plans to form an independent state in southern Yemen.

On March 14, Al-Zubaidi appointed Amr al-Beidh as his representative for foreign affairs. Prior to the appointment, Al-Beidh was responsible for external communications for the STC’s presidential council and previously worked in the office of his father, former President of South Yemen Ali Salim al-Beidh. In early April, Al-Beidh explained the STC’s role in the peace process in a series of tweets.

STC’s European Union Representative Pushes Two-state Solution

March 3: In an interview with Spanish news outlet Descifrando la Guerra (Deciphering War), the STC’s representative in the European Union, Ahmed bin Fareed, said he believes in a two-state solution. Bin Fareed highlighted the north-south divide as the dominant factor in the push for South Yemen’s independence. “We in the south think that all the northern forces have the same intention toward our land whether they are the Houthis, Islah Party or other political or military forces,” he said, adding that the EU was not supportive enough of the STC.

Protestors Call for Dismissal of Abyan Governor

Early March: The local authority in southern Abyan governorate sent a food convoy to Marib in support of the pro-government forces defending against Houthi incursions in the governorate. In response, protesters affiliated with the STC in Abyan’s capital, Zinjibar, demanded the departure of Abyan Governor Abu Bakr Hussein Salem. The protesters criticized Salem for sending aid to Marib while failing to provide adequate public services, such as fuel for the electricity plants in Zinjibar and Khanfar, districts of Abyan.

Taiz Governor Rallies Troops to Liberate Capital

March 11: Taiz Governor Nabil Shamsan ordered the mobilization of troops to force Houthi fighters from the governorate and end the siege on Taiz city which has been in place since 2015. In the televised speech, Shamsan offered a general amnesty to Houthi fighters who surrender to the internationally recognized government’s forces.

Protests Simmer Across Southern Yemen

Mid-March: Demonstrators in several cities across southern Yemen took to the streets to protest the deterioration of basic services including electricity and to demand payment of government salaries amid sharp rises in food and fuel prices. On March 15, in the city of Sayoun, in the central part of Hadramawt governorate, soldiers fired on a group of protesters who stormed the offices of the local authority, injuring at least six people. The headquarters of the internationally recognized government’s First Military Region is located in Sayoun. The next day, protesters in Abyan’s capital, Zinjibar, reiterated the calls of protesters earlier in the month for the dismissal of Governor Abu Bakr Hussein Salem. At the same time, about 65 kilometers to the west, in the interim capital Aden, protesters breached the perimeter of Al-Maashiq presidential palace, the internationally recognized government’s headquarters in the interim capital.

Second Wave of COVID-19 Reaches Southern Yemen

March 21: The Supreme National Emergency Committee for Coronavirus reported 140 new infections and 14 deaths, marking the largest officially recorded coronavirus-related cases and casualties since the outbreak reached Yemen. Importantly, scant levels of testing mean it is widely believed that the number of positive cases of COVID-19 is actually much higher. Two days later, the internationally recognized government’s COVID-19-monitoring body declared a health emergency. A UN graphic shows that the latest wave of reported infections started in late February. On March 31, 360,000 doses of the COVID-19 AstraZeneca vaccine arrived in Aden, where hospital workers overwhelmed by the latest outbreak complained of the lack of medical supplies to treat patients.

West Coast Commander Tareq Saleh Launches Political Platform

March 25: The National Resistance Forces led by Tareq Mohammed Abdullah Saleh, the nephew of the late former president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, announced the establishment of the Political Bureau for the National Resistance at a ceremony in the port city of Mokha, where his forces are based. The declaration comes amid US-led efforts to revive peace talks among Yemen’s warring parties to end the war. In this context, the new political body can be seen as an attempt by Saleh to secure a seat at the negotiating table. (See ‘The Battle of All Yemenis Against the Houthi coup – An Interview with Tareq Saleh’)

Socotra Sit-In Ends in Arrests

March 28: STC forces broke up a meeting of the Peaceful Sit-In Committee of the Archipelago of Socotra. The group opposes both the Saudi-led coalition and the UAE-backed STC. Several of the protesters were arrested, including the head of the committee, Mohammed Saeed Issa.

Hadramawt Governor Declares State of Emergency After Bloody Protests

March 30: Hadramawt Governor Faraj Al-Bahsani declared a governorate-wide state of emergency after a demonstrator was killed and several others were wounded during protests in the Mayfa’a area in the district of Brom Mayfa. Al-Bahsani also ordered the detention and suspension of coastal Hadramawt’s director of security, Major General Saeed Ali al-Ameri. A tribal negotiator intervened and Al-Ameri was released and resumed his work. Al-Bahsani reportedly flew to the UAE and then to Riyadh to discuss the situation with Saudi-led coalition leaders.

Hadi Government Claims Majority of Yemenis Live in Govt-Held Territory

April 4: The Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation released an infographic claiming to show updated figures on the geographical distribution of Yemen’s 2020 estimated population of 30.4 million. According to MOPIC, 48 percent of the population live in areas nominally under the control of the internationally recognized government, 46 percent of the population live in areas under Houthi control and the remaining 6 percent live outside the country as refugees. The infographic, which includes no methodology on how census data was gathered and analyzed, was published following criticism by some government officials of the widely-cited figure that Houthi-controlled areas contain about 70 percent of Yemen’s population. A footnote on the infographic states, “The continuation of war enhances the movement of more IDPs to legitimate areas.”

Iranian University Officials Announce Plans for Yemen Campus

April 5: In an interview with Iranian news outlet Mehr News Agency, Alaeddin Boroujerdi, head of international affairs at Islamic Azad University, said that the university is planning to open a branch in Yemen. It would be the first Iranian university in Yemen and reflects the strong ties between the Sana’a-based Houthis and Tehran. Boroujerdi said that the university had hit obstacles trying to obtain licenses to open branches in Iraq and Syria. “Syrian law does not allow a foreign university to be set up there, and Iraq has special rules, including the fact that the university’s founding board must be made up of Iraqis. But we are negotiating to get the necessary permits by agreement (there),” he said.

Swedish Diplomat Visits Marib

April 8: Sweden’s special envoy to Yemen, Peter Semneby, met with Marib Governor Sultan al-Aradah and visited IDP camps around Marib city during a visit to the governorate.

STC Swaps Government Officials for Soldiers in Prisoner Exchange

April 9: A prisoner exchange took place in Abyan governorate’s coastal city of Shoqra between forces loyal to the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and the internationally recognized government’s army. The STC released the director of Marib governor’s office, Mohammad al-Bazli, and four administrative staff, who were arrested while traveling to meet officials in Aden in March. In exchange, 15 STC-affiliated soldiers captured while fighting army forces in Abyan late last year were released.

Yemen’s Third-Largest Airport Reopens in Hadramawt

April 9: Yemen’s Civil Aviation Authority announced the reopening of Al-Rayyan Airport in Hadramawt’s capital city of Mukalla. Closed since Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) militants captured Mukalla in 2015, the country’s third-largest airport will operate domestic flights. An official in Hadramawt’s local government told Chinese news outlet Xinhua that the airport reopened with the help of the United Arab Emirates, whose military forces used Al-Rayyan’s facilities as a command center and as a prison after ejecting AQAP from the city in 2016. Yemeni officials announced the reopening of Al-Rayyan in late November 2019, but were forced to re-close the airport days later because they had reportedly not obtained licenses from the Saudi-led coalition to operate commercial flights.

Developments in Houthi-Controlled Territory

African Migrants Burned Alive in Houthi-Run Detention Facility

March 7: Scores of African migrants were burned to death in a Houthi-run detention center in Sana’a, after Houthi forces fired projectiles into a locked, overcrowded hangar. Houthi officials initially attempted to blame the fire on the UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM), but later took responsibility. Testimony from survivors indicated that the chain of events leading to the fire was sparked when detained migrants protested conditions in the facility, including Houthi attempts to extort money from the migrants for their release and forcibly recruit migrants to fight on the frontlines. In response, a group of prisoners went on hunger strike, which Houthi forces tried to end by force. When the migrants fought back, the Houthi forces locked them in the hangar and fired projectiles thought to be smoke bombs, tear gas canisters and/or flash-bangs inside, igniting the fire.

Houthi Transportation Minister and Former Army Chief of Staff Reported Dead

March 21: News of the death of Houthi Transportation Minister and former deputy army chief of staff Zakaria al-Shami surfaced on social media. The cause of death remains contested. Two unnamed Yemeni officials told Reuters that Al-Shami died from coronavirus-related complications in a hospital in Sana’a, where other Houthi officials, including the group’s prime minister, Abdulaziz bin Habtour, were treated recently for COVID-19. An unidentified Yemeni military official told Arab News that Al-Shami was killed a week earlier in a Saudi-led coalition airstrike while leading fighters in an offensive in Marib.

Houthi Security Head, Accused of Disappearances, Rape and Torture, Dead from COVID-19

April 6: Sultan Zabin, the director of the Houthi-run Criminal Investigation Department (CID) who oversaw the disappearances, rape and torture of dissidents and minorities in police custody, was reported to have died from COVID-19. The US Treasury Department and the United Nations Security Council had designated Zabin for sanctions in recent months. Zabin had “direct involvement in acts of rape, physical abuse, and arbitrary arrest and detention of women as part of a policy to inhibit or otherwise prevent political activities by women who have opposed the policies of the Houthis,” according to the Treasury designation.

Houthi religious authority rolls out new Ramadan rules

April 13: The Houthi-controlled General Authority for Endowments in Sana’a issued a circular outlining new religious guidelines during Ramadan. The document called for synchronizing the daily calls to prayer from loudspeakers in mosques throughout Sana’a and broadcasting speeches by Houthis leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi and religious awareness broadcasts from mosques’ loudspeakers. The General Authority for Endowments was created on January 30, 2021, taking over duties from the Ministry for Religious Endowments and Guidance. A day later, Abdulmajeed Abdulrahman Hassan al-Houthi, a member of the ruling Al-Houthi family, was appointed chairman of the new body.

Houthi Authorities’ Arrest of Fashion Model Highlights Women’s Rights Restrictions

April 11: The disappearance of Yemeni model and actress Entisar al-Hammadi in Sana’a became public after activists accused Houthi authorities of kidnapping her and two other women about a month earlier. On April 24, Al-Hammadi’s lawyer told Agence France-Presse that 19-year-old Al-Hammadi was arrested without a warrant on February 20 and public prosecutors had recently opened an investigation into the case. He said that the prosecution asked her questions related to “prostitution and immorality” in an attempt to frame the case as an “outrageous act,” based on the fact that “she did not wear the veil” in public places. The conservative Houthi government in Sana’a has greatly restricted women’s rights since coming to power in a coup in late 2014.

Houthi Forces Raid Shops Seeking Accounting Records and Religious Taxes

April 19: Houthi authorities launched an aggressive campaign to collect taxes in Sana’a and other areas under their control starting in mid-April. Shortly after Ramadan began, armed forces and intelligence officials raided businesses, demanding merchants hand over accounting records and increased amounts of zakat religious taxes. The seizure of accounting records is thought to be in preparation for imposing new taxes and royalties on merchants. The raids were carried out on behalf of the Houthi-run General Authority of Zakat, a quasi-state body established in 2018.

April 19: The president of the Houthi-run Supreme Political Council issued a decree changing the name of the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MOPIC) to the Ministry of Planning and Development and redefining its functions. The changes to MOPIC’s organizational structure were not spelled out, but Houthi authorities had stripped the body of its authority to deal with international aid donors and transferred those functions to the Supreme Council for Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (SCMCHA) in 2019.

International Developments

Donor Pledges Fall Short of Humanitarian Demands

March 1: International donors pledged US$1.67 billion for humanitarian assistance in Yemen for 2021, falling well short of the requested US$3.85 billion. Expressing disappointment at the fundraising effort, UN Secretary-General Antonio Gutteres said in a statement that the amount raised was “less than we received for the humanitarian response plan in 2020 and a billion dollars less than was pledged at the conference we held in 2019.” The drop in aid pledges stems from a combination of the global economic downturn during the pandemic and donor skepticism that the aid will reach intended beneficiaries in Houthi-controlled areas. Major donors, UN agencies and other international NGOs held an extraordinary summit in Brussels in February 2020 to highlight Houthi aid obstruction and demand an end to the practices.

Internationally Recognized Government Renews Qatar Ties

March 6: Yemen and Qatar marked their first diplomatic meeting since severing ties in June 2017, with Yemeni Foreign Minister Ahmed bin Mubarak meeting in Doha with Qatari Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani. While it remains unclear how the renewed ties with Qatar will affect the war in Yemen, Al-Thani stressed the importance of preserving Yemen’s unity and implementing UN Security Council resolution 2216. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt reconciled with Qatar in January, ending a blockade they had imposed in 2017.

Houthis, Iran Reject Saudi Peace Initiative to End War

March 22: Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan announced an initiative to take the first step toward political negotiations to end the war. Houthi spokesman Mohammed Abdulsalam quickly rejected the offer, stating there was nothing new in the Saudi initiative. On March 23, Iran’s ambassador to Sana’a, Hasan Irlu, rejected the peace initiative, saying on Twitter that a true peace initiative would stop the war, lift the coalition blockade, withdraw all Saudi military forces and support for “mercenaries and takfiris,” (referring to Yemeni forces) and start a Yemeni political dialogue without any external interference. A week later, Abdelmalek al-Ajri, a senior Houthi leader and member of the Houthis’ negotiating team in Muscat, Oman, rejected the Saudi initiative on the same grounds and called the cease-fire proposal an attempt to halt Houthi progress toward Marib.

Iran’s Military, Diplomatic Arms Spar Over Policy in Yemen

April 21: An assistant commander in the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force, General Rostam Ghasemi, told Russia Today in an interview that the IRGC had provided weapons to the Houthis early on in the war and trained Houthi forces to manufacture weapons, noting that there remains a small number of IRGC advisors in Yemen. It was the first public admission of Iran’s military support for the Houthis. On April 23, Iran’s Foreign Ministry refuted Ghasemi’s claims in a news release, stating that Iran’s support for Yemen is political in nature. The same day, Russian news outlet Sputnik published statements from an interview with Houthi political leader Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, who echoed the Iranian foreign ministry’s position and said Ghasemi’s comments may have been designed to provoke the Gulf states. Ghasemi himself responded to these counterclaims by stating that he meant what he said.

Throughout Yemen’s war, the UN has documented numerous instances of Iran violating a UN Security Council arms embargo that bans the shipment of weapons to the Houthis.

Casey Coombs is an independent journalist focused on Yemen and a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. He tweets @Macoombs

State of the War

By Abubakr al-Shamahi

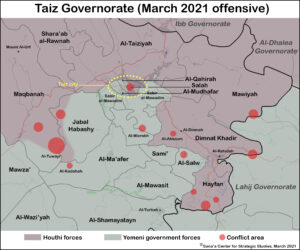

Government Offensive Pressures Houthis in Taiz

Yemeni government forces began an offensive in Taiz on March 3, leading to some of the biggest advances in the governorate since 2016. Frontlines that were previously stagnant, such as those in Al-Ma’afer district west of Taiz city, and Hayfan district in southeastern Taiz, witnessed significant advances by pro-government forces. The Yemeni government’s offensive came partly as a response to the Houthi offensive in Marib, and attempted to take advantage of the reduced number of Houthi forces on frontlines in Taiz. The renewed fighting in Taiz has also further empowered the pro-Islah Taiz Military Axis, which officially leads all Yemeni government military forces in the governorate. There are indications that the Taiz Military Axis is also seeking to impose its authority over areas on Taiz’s Red Sea Coast, currently controlled by the Saudi-led coalition-backed Joint Forces, led by Tareq Saleh.

While some fighting occurred within the city of Taiz, much of the fighting took place in areas west of the city, on the borders between the districts of Al-Ma’afer, Jabal Habashy and Maqbanah.

On March 9, Yemeni government forces took much of Al-Kadahah, northwest Al-Ma’afer, which gave them control over the road connecting the Red Sea Coast and the city of Taiz. Use of this road shortens the travel time between the port city of Mokha and Taiz city, and allows travelers to avoid treacherous unpaved roads they had previously been forced to take.

In Hayfan district, in the southeast of the governorate, Yemeni government forces, alongside ‘Popular Resistance’ local militias associated with Islah, attacked the Houthis on March 17, forcing them to withdraw from Al-Akboush and Al-Akawish. The areas sit near a mountain range that overlooks the Aden-Taiz road, as well as the Fourth Military Zone headquarters in Ma’abaq (Lahij), which the Houthis have been attempting to reach.

However, following these early successes, Yemeni government advances stalled. Initially, it appeared as though Yemeni government forces would attempt to consolidate their gains in Al-Kadahah and push further into Maqbanah district to the north. But throughout the second half of March and April a stalemate developed. This was partly a result of a lack of planning from the Yemeni government military, and partly the result of a Houthi decision to counterattack in certain areas they consider strategically important, rather than attempting to recapture all lost territory.

For example, on March 20, the Houthis sent heavy reinforcements into Bilad Al-Wafi, in the Jabal Habashy district, reversing recent gains by government forces in the area, most notably in Al-Sarahim and Sharaf Al-Aneen. Al-Sarahim overlooks the main road between Taiz and Hudaydah, a main supply route for the Houthis that they could not afford to allow to stay in government hands. Houthi forces also sent reinforcements to Al-Tuwayr, in southeastern Maqbanah, where they lost territory at the start of the offensive. The fighting in Al-Tuwayr was ongoing as of this writing. (For more, See ‘From the Frontlines in Taiz’)

Intense Fighting but Few Advances in Marib

The Houthi offensive in Marib continued in March, with the majority of the fighting in the governorate taking place west of Marib city in Sirwah district, specifically in the areas of Al-Mashjah, Al-Kassarah, Al-Zour and Al-Tala’ah Al-Hamraa. While fighting between the Houthis and Yemeni government forces has been intense, with heavy casualties regularly reported by both local media outlets and international media – including the death of the Yemeni government’s commander of the 6th Military Zone, General Ameen Al-Wa’ili on March 26 – there were few advances by either side. By the end of April, fighting assumed a back and forth nature as, despite frequent attacks, Houthi forces were unable to hold onto seized territory, as airstrikes from Saudi-led coalition forced them to retreat. The Houthis, however, continue to send waves of fighters forward for new attacks, and casualty numbers have been high in April, with international media outlets regularly reporting death tolls in the dozens. The dead include Muhammed Mashli Al-Harmali, the chief of staff of the government’s 7th Military Zone, whose death was announced on April 7, and the government’s Military Attorney General, Abdullah Al-Hadhiri, who was killed on April 24 in Al-Mashjah.

Houthi forces also continued to shell Marib city and its surrounding areas. The majority of these attacks have targeted the Yemeni government’s Third Military Zone headquarters in Marib city, but some have hit residential areas, resulting in civilian casualties.

Fighting between the two sides also continued in Jawf governorate, to the north of Marib. The Houthis made small advances in Al-Alam, southeast of the governorate capital Al-Hazm, on March 5, while the Yemeni government’s military claimed to have advanced in the Al-Madabiq mountains, in western Jawf’s Bart Al-Anan district, on March 26.

Fighting Escalates in Hudaydah; New Government Offensive in Hajjah

After a relatively quiet February, fighting escalated in and around the city of Hudaydah in March, with battles between the Houthis and the Joint Forces taking place primarily in the city’s eastern frontlines. Neither side made any advances, but casualties were high – in the last week of March over 100 fighters died on both sides, according to medical sources. The Houthis called up reserve forces and police officers to fight on the city’s frontlines in an effort to bolster their numbers.

The Saudi-led coalition conducted airstrikes throughout the month on Houthi targets in Hudaydah, primarily focused coastal areas in an apparent effort to damage the Houthis’ naval capabilities. Some airstrikes also hit civilian facilities, including a strike on March 22 that hit the Al-Saleef grains port, north of Hudaydah city. A warehouse and the living quarters of a food production company were hit, and the UN observer mission in Hudaydah said that six injured workers were transferred to local medical facilities for treatment.

Further north along the Red Sea Coast, in Hajjah governorate, the Yemeni government launched an offensive on March 12. Fighting in Abs district on the border with Saudi Arabia had some initial successes, with the Yemeni government claiming on March 14 that its forces had taken a dozen villages, including Al-Manjourah, Al-Hamraa, Al-Jaraf, Al-Shabakah and Barman. There were no reports of further advances in the second half of the month or in April.

Houthis Pepper Saudi Arabia with Cross-Border Attacks

The Houthis claimed a number of aerial attacks on Saudi territory in March, a continuation of the group’s escalation of cross-border operations since the beginning of 2021. Although the majority of the projectiles fired by the Houthis were intercepted by Saudi Arabia, the Houthis continue to demonstrate the ability to strike Saudi territory. On March 7, a Houthi missile and drone attack targeted a Saudi Aramco oil storage yard at Ras Tanura, on Saudi Arabia’s Gulf coast. The Saudi defense ministry said it intercepted the armed drone before it hit the storage yard, adding that shrapnel from a ballistic missile fell near a residential compound used by Saudi Aramco in Dhahran. Additionally, a Houthi attack on March 19 started a fire at a Saudi Aramco oil refinery in Riyadh, and a March 25 attack led to a fire at an oil facility in southern Saudi Arabia’s Jizan province. On April 12, the Houthis once again showed their capability to hit targets deep into Saudi territory, when they fired projectiles at Saudi Aramco facilities in Jubail, in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, and Jeddah. The attacks were part of a salvo that included 17 armored drones and two ballistic missiles, and also hit targets in Khamis Mushait and Jizan, according to the Houthis.

For its part, the Saudi-led coalition also stepped up its airstrikes in Sana’a, hitting Houthi targets across the capital, such as the Al-Siyanah base in northern Sana’a, and the Al-Haffa base in the east of the city. Airstrikes on Sana’a on March 21 and March 22 bookended the Saudi announcement of a cease-fire proposal. More than 400 Saudi-led coalition airstrikes were reported in April, with the majority targeting Houthi forces in Marib governorate.

Escalation in AQAP-linked Attacks in Abyan

March saw an escalation in the number of suspected Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) attacks in southern Yemen’s Abyan governorate. The attacks primarily targeted current and former membersof the Southern Transitional Council’s Security Belt forces, which actively fought against AQAP in Abyan prior to 2018. Five separate AQAP-linked attacks were reported in March, killing at least 11 Security Belt fighters. The deadliest attack, on March 18, saw a group of gunmen believed to be AQAP members attack a Security Belt checkpoint in Dahoumah, eastern Ahwar district, in Abyan’s southeast. The attack killed five civilians and seven Security Belt fighters.

Government – STC clashes in Abyan Threaten Stability in the South

Intermittent clashes broke out in eastern Abyan in April between Yemeni government and STC forces. The Yemeni government’s Special Forces and the STC’s Security Belt forces had agreed to jointly patrol Ahwar district after the rise in AQAP attacks, as well as criminal activity, in February and March. However the presence of rival forces led to clashes, initially sparked on April 5 after Security Belt forces raised the flag of the former South Yemen over a checkpoint in Khabar Al-Maraqishah area, Khanfar district, eastern Abyan. One Yemeni government soldier was killed in that fighting, which, despite local mediation efforts, resumed on April 9 and continued until the next day.

Fighting also broke out on April 16 in western Ahwar district, before local mediators intervened and stopped the fighting on the same day. No clashes were reported during the rest of the month.

Abubakr Al-Shamahi is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

Economic Developments

By the Sana’a Center Economic Unit

Update on Local Exchange Rates

During the months of March and April, the exchange rate in Houthi-controlled territories remained around the 600 Yemeni rial (YR) per US dollar. Houthi authorities continue to prioritize the maintenance of exchange rate stability, aided by the continued enforcement of a ban on new Yemeni rial banknotes (i.e. those issued by the Central Bank in Aden after September 2016) in Houthi-controlled territories.

In sharp contrast, the value of the Yemeni rial in areas outside of Houthi control fluctuated during March and April. On March 2, the value of the rial stood at YR884 per US$1 dollars, and on March 9 depreciated to YR913. At the end of March, the rial stood at YR830 per US$1 dollar, following an appreciation on the back of news that Saudi Arabia pledged a US$422 fuel grant to Yemen, and that the Panel of Experts on UN had withdrawn corruption accusations lodged against the Central Bank in Aden in its annual report. As has proven to be the case in the past, the appreciation of the Yemeni rial in non-Houthi areas in response to certain political or economic announcements/developments was short lived. On April 1, the rial dropped to YR861 per US$1. By April 23, the value of rial fell further to YR900 per US$1.

Government Presents Fuel Data in Defense of Reduced Fuel Import Activity at Hudaydah

On April 2, the Supreme Economic Council for the internationally recognized Yemeni government published fuel data that examined nationwide fuel import activity between January and March 2021 and compared this data with fuel import data recorded in 2020 and 2019 for the same period.

Yemen Fuel Import Activity Between January and March 2019, 2020, and 2021 (in metric tons)

|

Port |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Hudaydah |

459,422.64 |

710,803.62 |

84,517.86 |

|

Aden |

289,773.87 |

318,833.89 |

590,235.87 |

|

Mukalla |

110,964.13 |

182,918.03 |

291,750.65 |

|

Nishtun |

23,400.00 |

16,353.30 |

86,873.41 |

|

Total: |

883,560.64 |

1,228,908.84 |

1,053,377.79 |

Source: Supreme Economic Council for Internationally Recognized Government

The government released this data in a briefing note in an apparent attempt to allay fears over remaining fuel supplies in Yemen, particularly in the more densely populated Houthi-controlled territories where up to 70 percent of Yemen’s 31 million people reside. From January until the end of February 2021, only one shipment of cooking gas entered Houthi-run Hudaydah port, with no other fuel import activity recorded. In March, however, the government issued clearances for five fuel shipments to enter and unload at Hudaydah, but only one of the shipments that arrived was for general sale to consumers.

Similar to the last period of reduced fuel import activity at Hudaydah (June-September 2020), the government has sought to mitigate the impact of reduced fuel imports at the Red Sea port by authorizing additional fuel imports via Aden, Mukalla, and Nishtun ports in government-held areas, with the expectation that fuel would then be transported overland to Houthi-held areas. In the briefing note published on April 2, the government claimed that from January to March 6,000 metric tons (MT) of fuel was transported overland daily from areas outside Houthi control to Houthi-held areas. Using the government’s own estimates, this would mean that from January to March a total of 540,000 (MT) was transported overland to Houthi-held areas, equivalent to 51 percent of the total 1,053,377.78 MT the government said was imported into Yemen.

Fuel has and continues to be transported overland from areas outside Houthi control to Houthi-controlled territories. There are frequent upticks in overland fuel transfers during repeated periods of prolonged standoff between the government and the Houthis over Hudaydah. It is, however, difficult to quantify and confirm daily overland transportation activity. Doing so would require greater insight into the amount of fuel traffic that passes through Houthi inland customs checkpoints as well as knowledge of other, more irregular, routes that truck drivers take.

The government is eager to play down concerns over available fuel supplies in Yemen. In addition to highlighting fuel import activity, it also accuses the Houthis of withholding fuel from the local market in areas they control. It is almost certain that there are fuel shortages in different areas of the country, including government areas as fuel traders look to transport supplies to Houthi-held governorates, given the potential for greater profits due to the higher fuel prices there. The extent and severity of these shortages remains unclear, with both the Houthis and the government looking to either play up or conversely play down resultant humanitarian concerns.

Saudi Arabia Pledges US$422 million Fuel Grant for Govt Areas

On March 30, Saudi Arabia announced that it would provide Yemen with a US$422 million fuel grant via the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen (SDRPY). Riyadh stated that the fuel would be for electricity power generation, but did not initially specify in which exact areas the fuel would be sent, distributed and subsequently used. On April 13, the Saudi Press Agency reported that the fund would purchase 1,260,850 metric tons (MT) to power “more than 80 power stations” in areas that fall under the government’s administrative control. Saudi Arabia previously provided Yemen with a US$180 million fuel for electricity grant, spread out over a six month period from October 2018 till the end of March 2019. The fuel was delivered via three separate shipments in October and December 2018 and January 2019, which were then distributed and used in areas nominally under the government’s control.

Panel of Experts Revise Analysis of CBY-Aden

At the end of March the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen withdrew its earlier accusations lodged against the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden related to its handling of the US$2 billion deposit provided by Saudi Arabia in March 2018. The economic section of the latest UN Panel of Exports report circulated at the end of January 2021 included accusations that the central bank in Aden had engaged in “money-laundering and corruption practices.” In addition to the Panel of Experts telling the UN Security Council to disregard this particular section, pending a final review, the author of the economic section, Mourad Baly, also withdrew his name from consideration for re-nomination. (For commentary, see ‘The Corruption is Real: UN Panel Should Not Have Retracted Embezzlement Accusations’)

Shabwa Local Authority Cancels Agreement for Qana Port Development

On April 11, the local authority in Shabwa announced the cancellation of a standing agreement with QZY Trading LLC over the development of Qana port. Ahmed al-Essi, one of Yemen’s most prominent businessmen and deputy director of the President’s Office, is a shareholder of QZY Trading LLC. The first shipment of fuel (17,000 MT of diesel) unloaded at Qana in mid-January. The reasons behind the cancellation of the agreement between the local authority and QZY Trading LLC has been subject to a lot of local media speculation, with the Shabwa local authority accusing Al-Essi and QZY Trading LLC of refusing to sell 35 percent of any fuel shipment via Qana to the local Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) branch at cost (the price at which they purchased the fuel plus the cost of shipping it to Qana). For its part, QZY Trading LLC stated that this condition was not part of the original agreement with the local governing authority.

Houthis Temporarily Open YPC Fuel Stations in Sana’a

On April 20, the Houthi-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) temporarily reopened a number of fuel stations in Sana’a and sold petrol and diesel at a rate of YR11,000 per 20 liters. This was a marked increase from the previous ‘official’ rate of YR5,900 per 20 liters at YPC stations, but was, however, YR2,000 less than the price at privately-owned fuel stations. The YPC fuel stations remained open for roughly 48 hours before closing again, with fuel once again being only available on the ‘parallel’ or ‘black’ market at a price of YR13,000 per 20 liters. The temporary reopening of YPC stations and the sudden increased availability of fuel at those stations raised suspicions over potential fuel stockpiling and the validity over claims of fuel shortages due to decreased fuel imports via Hudaydah port from January through April.

Sana’a Chamber of Commerce and Industry Denounces Houthi Zakat Authority

On April 18, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry – Amanat al-Asimah issued a statement denouncing ‘harsh’ and ‘extreme’ measures adopted by the Houthi-run Zakat Authority in April, namely the deployment of armed security and intelligence officials at different commercial stores and private sector enterprises to demand access to their internal data. The Chamber of Commerce and Industry – Amanat al Asimah also expressed its opposition to the damage caused by the fact that a number of stores were forced to close at the behest of the security and intelligence officials. The moves are seen as part of an attempt to increase zakat and general tax revenues, with taxation serving as a reliable source of funding for the Houthi movement.

Features

Reflections on the 2011 Yemeni Uprising a Decade On

January 15: The Day I Wore a Revolution

By Bilqis Lahabi

I was in Tunisia on December 17, 2010. The workshop I was attending in Tunis was in a frenzy, everyone worriedly whispering about the young Tunisian man in Sidi Bouzid who had set himself on fire, kicking off a wave of protests in the city.

I returned to Sana’a, but my thoughts, along with those of the world, remained focused on Tunisia and the growing protests. I was watching them at a friend’s house when on January 13, 2011, Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali said “I have understood you” to the people, and left for exile. It was a moment that awakened emotions of hope and revolution: an urge to cry, a sense of joy, awe and amazement. The exclamations were in throats and in our hearts, as we recited the Tunisian poet Abu al-Qasim al-Shabbi’s words: “If, one day, the people will to live…” Who among us did not will what was happening?

That night, we ended our gathering and everyone silently went home. Later, I got a message from a friend, Fatimah Mutahar, suggesting that we make a public gesture to express our joy and solidarity with Tunisia.

On January 14, I sent an open invitation on Facebook to gather the next morning in front of the Tunisian Embassy in Sana’a. I’d never done anything like this before, so I asked for help. Eventually, a colleague, Abdulrasheed Al Faqih, helped me draft and send the invitation:

A call for a celebratory gathering in front of the Tunisian Embassy at 10 a.m. on Saturday, January 15, 2011.

The invitation soon found its way to Fakhriah Hujairah, an activist who sent it to her network of university students, youth political party members, activists and journalists. I may have written the invitation, but Fakhriah made it an event.

The night before our event, I could hear my heart beating in my chest, I could feel tears running down my face. Tears I couldn’t bother to dry as I imagined the moment of liberation from a corrupt regime. I was at home, alone, unable to sleep, like a child the night before Eid. What should I wear? What color do you wear to a revolution? I decided on orange, the color of the revolution in Ukraine. Orange would be a welcome change from the uniform black abayas.

The next morning, I arrived well ahead of time. There were a few media outlets covering the event. I told the Al Jazeera correspondent, Hamdi al-Bukari, that I wanted to send a message to President Ali Abdullah Saleh. Standing in front of the door to the Tunisian Embassy, with the Tunisian flag behind me, I said: “If he has been threatening us with Iraqization, Afghanistization, or Somalization, we are now threatening him with Tunisization!” It was a moment in my life that I had never expected, yet once I said those words it felt right.

In a nearby street, university students were marching and chanting the first line of what was quickly becoming the poem of the revolution: “If, one day, the people will to live, then fate must obey.”

In that small space in front of the Tunisian Embassy, there were roughly 15 activists and journalists, arguing with the security forces sent in to detain them. The marching students were blocked from joining us, but the chanting did not stop.

Bilqis Lahabi is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies where she focuses on Yemen’s political and social developments.

The Other Side of the Wall

By: Salah Ali Salah

“Shame, Shame; Peace is met with violence.” Despite hearing these chants hundreds of times, it was a very different experience that Friday because I was not inside the square. I was on the other side of the wall, with the perpetrators.

March 18, 2011, the Friday of Dignity, is a day that cannot be forgotten in Yemen. I was at home in Sana’a, near the Change Square, south of the old university campus. I was shocked when my wife told me they burned the square. I went to the window, and saw smoke rising from the direction of the protests, a TV channel news team in the building across the street, filming in the direction of the square, and a helicopter flying over the square.

Neighborhood chiefs and regime supporters had warned us: “If the protests expand, they will search your women before allowing them to come home! They will not let you sleep at night! They will turn the street outside your homes into public bathrooms! If your children go out into the street, they will harass them!”

Cement walls were erected around the square, with funding from the regime and protection by security forces. They separated the surrounding neighborhoods from the protesters in the square. Some of these walls had doors built into them, and they were guarded by men in civilian clothing from the neighborhoods, who would harass the protestors and sometimes not allow them to enter the square.

I left my home, heading toward the square. We were used to the Central Security Forces officers at the entrance, searching everyone going in for weapons. But on that day, they weren’t there. Instead, at each intersection, there were men in civilian clothes forming human chains to stop people from reaching the square.

The largest group of these men was near the first line of contact with the square, behind the wall that had been built across Ring Road. A number of tires had been placed on the wall and burnt by regime supporters. This was the source of the heavy black smoke that I had seen from my window.

Some of the men were carrying clubs, others were carrying automatic rifles. There were also signs demanding that the protesters leave the street and explaining the problems that they were causing for the residents of the areas surrounding the protests. One of the signs had a saying by the Prophet: “Avoid sitting on roadsides.”

On my way to the square, I was called over by one of the masked gunmen. I recognized him and asked: “Where are you going with a weapon? It would be horrible for you to be involved in bloodshed.” He showed me the ammunition in his gun, saying: “Don’t worry, these are all blanks, we just want to scare them.” As I continued walking near the wall, both sides began throwing rocks.

A few minutes later, a transport truck arrived, carrying soldiers wearing the uniforms of Thunderbolt Forces. They were young, and their shaved heads suggested they were new recruits. They were only carrying clubs, no other weapons, helmets, or protective vests. These were the victims, the sacrificial lambs the regime sent to antagonize the protesters.

The protestors responded with rocks, and the soldiers were bloodied. The regime had the images it wanted. It wanted to show that the protestors struck first.

Some of the regime supporters defending the wall grabbed one of the retreating soldiers, yelling: “Where are you going! Go back and defend the country!” The soldier responded: “Those sons of dogs sent us here with just sticks, as if we came to play golf.”

On the other side of the wall, I heard someone on a megaphone yelling, encouraging the protestors to break through the wall. “Heaven awaits you on the other side.” But I was on the other side, and I was not in heaven.

Some of the upper parts of the wall started to collapse, and the sounds of gunfire towards the protestors were getting louder. There were masked regime gunmen on top of a number of buildings, some of whom were snipers, in addition to the gunmen on the ground, including my friend with the ‘blanks’.

Outside the walls, we were not afraid of the bullets, because all the shooting was all coming from our side.

At that time, we did not know what was happening inside the square. One of the residents of the neighborhood came to talk to the “non-participants” who had gathered, including myself. He said: “Look how much these people in the square lie. They just said on television that there have been more than 30 people martyred!” It seemed many people believed the story that only blanks would be used to scare the protestors.

The situation continued to escalate. After a while, well-equipped security forces arrived, along with a water cannon truck and tear gas. The soldiers started to spray the protestors with water and tear gas as the wall broke apart.

I went back home because of the tear gas and to see the news on the other side. What I saw was shocking. There were more than 54 martyrs from these clashes.

Ali Abdullah Saleh said in a statement that the killings were carried out by neighborhood residents negatively affected by the protests. A group of snipers accused of killing the protestors were taken to the headquarters of the First Armored Division, commanded by Ali Mohsen al-Amhar. There are no accurate reports about their identities or what happened to them, but it is likely that they were released. Certainly, they never faced any trial. There are still many secrets surrounding the Friday of Dignity and the 2011 Revolution.

A few days before that Friday, Khalid al-Hazmi had visited me at my home. An enthusiastic and cultured young man, he passionately tolds me about the importance of change and establishing an organized youth bloc to save Yemen. He was one of the martyrs inside the square that day.

Was his blood and that of his fellow protesters shed for nothing? Will Yemen one day be able to achieve the change that they dreamed of and sacrificed for? Who knows. There are no answers to these questions. Just as there are no answers to as to when this war will end or when peace will come to Yemen.

Salah Ali Salah is a researcher at the Sana’a Center. He previously served as director general of the monitoring and technical inspection unit at the Supreme National Authority for Combating Corruption.

The Yemen Uprising: The View from Turtle Bay

By: Casey Coombs

In January 2011, as Yemen’s Arab Spring-inspired protests were taking root, I was just starting out as a journalist at UN headquarters in New York. The revolutions spreading across the Middle East and North Africa had breathed new life into the UN Security Council (UNSC), whose responsibility to tackle threats to international peace and security had taken a back seat during the US-led war in Iraq.

But Yemen’s uprisings didn’t make it onto the agenda of the 15-nation UNSC until October 2011, when Tawakkol Karman, a 32-year-old pro-democracy activist and member of Yemen’s main opposition party, Islah, visited UN headquarters to lobby for action against the latest violent crackdown on peaceful protestors. Karman had just been awarded the Nobel Peace prize for her role in the youth-led uprising against 33-year ruler President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had survived an assassination attempt in June 2011 after loyalists shot and killed at least 50 protesters in March. In late September, Saleh resurfaced in Yemen’s capital Sana’a after several months recovering in a hospital in Saudi Arabia. His unexpected return coincided with yet another bloody crackdown on peaceful protestors and open street battles between Saleh’s Republican Guard and forces loyal to General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, who had defected months earlier.

While Yemen’s revolution was taking a turn for the worse, UNSC work back in New York had ground to a halt over fallout from the council’s authorization of a NATO-enforced no-fly zone over Libya to protect civilians against forces loyal to President Muammar Qadhafi. The no-fly zone quickly morphed into a bombing campaign aimed at regime change in the eyes of Russia and China, whose UN ambassadors accused their counterparts from the United States, France and the United Kingdom of taking advantage of the humanitarian intervention. Together, they represented the five permanent members of the council and the only ones with veto power, meaning any one of them could block interventions in similar contexts, like Syria. Indeed, Russia and China both vetoed Western-drafted UNSC resolutions aimed at curbing Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s nascent crackdown, which had killed an estimated 2,600 people by mid-September. The UN estimates that the death toll from the conflict in Syria now stands at least 400,000.

The ensuing diplomatic deadlock among the permanent five members limited the chances that the UNSC would heed Karman’s demands to reject a Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) plan to offer President Saleh immunity in return for his resignation. Karman also asked the council to freeze the assets of Saleh and his inner circle and refer them to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Three days after Karman’s arrival, the UNSC unanimously passed Resolution 2014, which endorsed the GCC initiative and mapped out the political transition that UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s recently dispatched special advisor to Yemen, Jamal Benomar, would promote.

“The importance of this resolution is that it’s unanimous,” U.K. Ambassador Mark Lyall Grant, the “penholder” of the Yemen file at the UNSC, said at the time. “It’s a very strong condemnation, a very strong call from the united international community. And I think that’s what gives the power to this resolution.”

Of course, that resolution along with the UN-backed political transition ultimately collapsed three years later when Saleh allied with the armed Houthi movement and overtook the capital in a military coup on September 21, 2014. The Security Council sanctioned Saleh and Houthi leaders within a few months of the coup and imposed an arms embargo in April 2015, but the measures did little to stop the alliance. Today, Yemen has a third UN Special Envoy and the Security Council continues to reiterate condemnations and calls to end the war and rebuild Yemen as a functioning state.

Casey Coombs is an independent journalist focused on Yemen and a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. He tweets @Macoombs

How the Fractious Elite Hijacked the Yemeni Uprising

By Abdulghani Al-Iryani

The Yemen Youth Uprising of 2011 lasted for just a few weeks until it was taken over by traditional political forces. Leading these forces was the Islah party, whose leaders were partners with the regime, sharing economic benefits with then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh through most of his tenure. A large faction of Saleh’s own camp, led by General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, also defected to the side of Islah. From that moment – March 18, 2011 – the uprising became a power play between two factions of Yemen’s ruling elite. Their tense confrontation deteriorated into military conflict and an assassination attempt on Saleh, before wisdom prevailed and a deal for a transfer of power from Saleh to his vice president was reached.

A national dialogue conference sponsored by the UN stipulated an ambitious progressive power and wealth-sharing arrangement, but failed in three key areas. It lost credibility by violating its own bylaws, it lost relevance to the general public by omitting meaningful outreach, and most important of all, it tried to take from the ruling elite more than what was really needed to carry out a successful transition, triggering strong resistance.

The power-sharing arrangement that followed was dominated by members of the ruling elite who had defected from Saleh, namely the wealthy businessman and politician Hameed Al-Ahmar and army General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, ensuring the continuation of the same corrupt system but with fewer people to share the benefits. Disaffected parties such as Al-Hirak, or the Southern Movement, gave up on the political transition and demanded outright secession for the South. The two confessional components of the Yemeni body politic, the armed Houthi movement and the Islah party, seeing that the central state had weakened, raced to take over military camps in Sa’ada and Al-Jawf, giving us a glimpse of what was to follow: violent conflict and polarization along identity lines.

Yemen has five main identity blocks. They are geographically and economically defined, and each has developed its own distinct social, cultural and linguistic features. These identity blocks, each of which has deep historical roots, have been vehicles for mobilization and conflict through the ages. Starting from the east, they are defined geographically as follows:

- Hadramawt

- The Mashreq (Bedouins of the desert region from the Saudi border to the Arabian Sea, including Al-Jawf, Marib, Shabwa and eastern Abyan governorates)

- The Northern Highlands

- Middle Yemen (the region historically called Yamnat or Yemen, includes a mix of tribes and peasants in Ibb, Taiz, Lahj, Aden, Al-Dhalea and western Abyan);

- The Tehama, the western coastal plain that historically extended deep into current Saudi Arabia).

These identities competed throughout history, as great dynasties rose and fell in each one, sometimes controlling all the territory historically defined as Yemen. During the past century, the Northern Zaidi tribes of the highlands dominated North Yemen. In the South, protection treaties with Great Britain helped maintain 23 autonomous entities until independence in 1967.

Since independence, the Bedouins of Abyan-Lahj have clashed with the tribes of the western governorates, culminating in the bloody 1986 civil war. The 1994 civil war followed a similar course, with the Bedouins of Abyan-Shabwa fighting on the side of the central government (Northern) forces against the Yemen Socialist Party’s (Southern) forces.

The events of 2011 and subsequent war followed the historical pattern of political movements that attempted to break the monopoly of power held by the Northern-Tribal-Zaidi (NTZ) elite. Previous examples of such attempts include the 1948 Constitutional Revolution and the 1962 Republican Revolution.

But the 2011 popular uprising, and the international support it received, was the greatest challenge to NTZ elite dominance in modern history. This was not because of the strength of the opposition, but rather because of the divisions within the NTZ elite that paralyzed it and made it possible for other political components to claim a share of power.

Saleh is often lauded for surrendering power peacefully. It is time to dispel this myth. According to Dr. Abdul Karim Al-Eryani, a former prime minister and leading political figure in Yemen (full disclosure: he is also my uncle), Saleh met with his generals for three consecutive days prior to signing the GCC initiative in November 2011, asking them to study military options for breaking the youth sit-in in Sana’a’s Change Square. At the end of each meeting, their assessment was that the military option was not viable and only the political option was acceptable. In a sense, Saleh was asking them if they would stay loyal if he resorted to force. They were saying no. On the third day, the meeting ended mid-day, and by 4 p.m. Saleh was already in Riyadh, ready to sign the GCC initiative.

The NTZ elite was so fractured after defections to the opposition that it was not possible for Saleh to convince his loyalists to fight. He resigned, and while he left office, as first promised in a public speech during the 2006 presidential election campaign, he also kept the transitional government dizzy with all manner of political sabotage.

The NTZ elite defectors dominated the two-year transition. Hameed al-Ahmar in particular acted as heir-apparent to the transitional president. The new president, Saleh’s former deputy Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, made feckless and failed attempts to assume control by removing powerful figures of the old regime, succeeding only in convincing the NTZ elite to close ranks to defend their privileges.

However, Saleh was not ready to forgive the defectors. Saleh also believed he did not need them. He had a better alternative — allying with the NTZ elite faction that had never been part of the republican state: the Houthis. (Sa’adah was the royalists’ base during the 1960s. After the 1970 peace agreement that ended the North Yemen Civil War, the royalist tribes surrounding Sana’a were fully incorporated into the republican state while others further north were left out of the deal.) According to an eyewitness, Saleh gathered a large number of NTZ tribal sheikhs in November 2011 and told them that if they wanted to stay in power, they must go to the “Sayyed”, meaning Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi.

Saleh’s alliance with the Houthis reversed the changes of 2011-12, but his hope to control the Houthi movement and become the leading partner was quickly dashed by the Houthis’ organizational strength, their ideological commitment and their unconditional loyalty to their temporal and religious leader, the ‘Sayyed”.

Eighty years of trying to break that dominance model should be enough for Yemenis to realize that the problem is not in the nature of the NTZ demographic. It is in the concentration of power in Sana’a (or, in the case of southern Yemen, in Aden). There is no conceivable way to achieve stable and meaningful power-sharing in a centralized state. The power and economic benefits it reaps need to be diffused to prevent a power monopoly from emerging again.

The determined fists and the bare chests of the protesters of 2011 did much to dismantle the old regime that was decaying and leading the country to economic and political breakdown. But the disastrous mistakes and failures that followed have brought the Yemeni state to the brink of destruction. The two factions of the elite, the one that resisted change and the one that hijacked Change Square, bear the responsibility for that.

Abdulghani Al-Iryani is Senior Researcher at Sana’a Center. He has served as senior Advisor to UNDP Yemen and to the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary General to Yemen.

A Decade of Shattered and Betrayed Dreams

By Mohammed Al-Qadhi

Like most things, Yemen’s 2011 uprisings can be divided into a before and an after: The world that existed before March 18, 2011, and the one that remained after. Before that Friday, anything – no matter how big or outlandish – seemed possible. That January we watched as Tunisian president, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, fled his country for exile. Days later, on February 11, lightning struck again. Hosni Mubarak, who had ruled Egypt for nearly 30 years, resigned the presidency. Could Yemen be next? Would Ali Abdullah Saleh follow his fellow presidents-for-life in stepping down?

I remember those early days in Sana’a, watching the vanguard of the uprising – young students and activists – take to the streets in front of Sana’a University. They believed in miracles. What started as a protest of solidarity and support for the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt quickly took on a local flavor.

The small nucleus of students and activists attracted more protesters, who in turn attracted others, all of whom chanted: “Leave, Leave.” That refrain echoed down Ring Road, spreading throughout the city.

Soon, people had pitched tents of different shapes, sizes, and colors, as diverse as the protestors themselves. Everyone wanted a change, a new beginning. There was momentum, hopes and dreams, and the belief that what had happened in Tunisia and Egypt might happen in Yemen as well.

Then came that Friday, March 18, 2011. The protestors called it Juma’at al-Karamah, the Friday of Dignity, but the Saleh regime had other ideas. Shortly after noon prayers, snipers stationed around the square opened fire on the protesters, gunning down dozens in a politically motivated massacre.

That was the day everything changed. The snipers succeeded in killing the peaceful protest that day, but they also sowed the seeds of the regime’s destruction. Shortly after the massacre, as the wounded were still being attended to, Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, the most powerful military commander in the country and one of Saleh’s closest allies, announced that he was breaking with the president to stand with the protesters. Ali Mohsen’s defection opened the floodgates. Within the hour, dozens of government officials, ambassadors abroad, military commanders and tribal sheikhs publicly declared their support for Yemen’s uprising.

For a moment, it looked like the end of Saleh’s regime and victory for the peaceful protests. But the defections from the army militarized the peaceful uprising. Eventually, the protests were co-opted by the opposition – the Joint Meeting Parties (JMP) – and Change Square was turned into one more piece of political leverage. The JMP went to negotiations as if they represented all the protesters across the country. Ali Mohsen’s men in the 1st Armored Division moved in to protect the protesters at Change Square. I remember wondering at the time why peaceful protestors needed to be protected by armed units. That was the trap. When you militarize a peaceful uprising you don’t get victory; you get conflict.

The fighting started in Al-Hasabah neighborhood and around the protesters then spread within Sana’a, eventually culminating in the blast at the presidential palace mosque, which nearly killed Saleh, who was airlifted to Saudi Arabia for surgery.

It took months of negotiations to implement the Gulf Cooperation Council Initiative for a transfer of power and for Saleh to agree to step down. Finally, in February 2012, Saleh resigned in favor of Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who was supposed to serve as interim president for two years. The National Dialogue Conference was held, plans were discussed, and the future began to take shape. Then, the entire project blew up. There is plenty of blame to go around, but much of it was the fault of the Houthis.

The JMP, which depended on the support of the international community, was so busy competing over portfolios and positions that they forgot Saleh had not gone into exile or to prison. He was at home, waiting and plotting. Saleh’s revenge would eventually embroil the country in a civil war and lead to its collapse.

In late 2014, Saleh allied with his former enemies, the Houthis, to take Sana’a and as they placed Hadi and his cabinet under house arrest. Hadi eventually managed to escape to Aden and then Saudi Arabia, but the Houthi-Saleh forces were on the warpath, storming into Aden and bombing the presidential palace with fighter jets. Days later, in March 2015, Saudi Arabia launched Operation Decisive Storm. The operation, which was supposed to last a few weeks and restore Hadi to power, has dragged on and on. We are in the seventh year of this conflict, which has destroyed Yemen and made it the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

A decade on, Yemen’s 2011 generation has mostly either been killed, wounded, displaced, made homeless or helpless. The students and activists lost and war won. As soon as the peaceful protests were hijacked by influential political, military and tribal groups, it was over.

I’ve spoken to many of these young activists, most of whom do not regret what they did, only that the revolution was betrayed and manipulated. And the same parties that hijacked the revolution have also hijacked the armed resistance against the Houthis. The result is the current catastrophe.

After six years of suffering and this ill-fated war, the issues that the peaceful protesters brought up a decade ago still need to be addressed, primarily building a state based on the rule of law and equal citizenship. If they are not, all attempts at peace will fail. There is still hope a decade after the Friday of Dignity. One day this conflict will end and a state will be built again, rising from the ashes. When that day comes perhaps then the protesters will emerge victorious.

Mohammed Al-Qadhi is a Yemeni journalist and analyst. He has reported for Yemen for more than two decades. He is currently a reporter for Bloomberg News and a political advisor at the Geneva-based Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. His twitter account is @mohammedalqadhi.

Dignity is in Aspirations, Not in a Wall

By Bilqis Lahabi

Years have passed since March 18, 2011. Yemenis continue to shed their blood against a wall that they believe represents their dignity, a wall that will never be satisfied. It is a wall built by decades of repressive regimes that institutionalized ignorance and corruption in the societies they ruled. Yemen, as a land and as a people, is being destroyed as it attempts to bring down this wall. Anyone that confronts this wall either wastes away, disappears, or becomes a part of the wall and its system.