The Long March to Peace

Peace talks between Saudi Arabia and the Houthi group (Ansar Allah) dominated Yemeni politics over the last year. The negotiations began as backchannel discussions in October 2022 after the Houthis resisted UN pressure to renew a truce first agreed in April 2022 by making a series of eleventh-hour demands. The talks continued despite Houthi attacks on oil terminals in southern Yemen in late 2022 that effectively put the internationally recognized government under a form of economic blockade. As the months progressed, the government’s increasingly dire economic situation pressured it to accept the Saudi policy of seeking a settlement with Houthi authorities, seemingly at almost any price. The broad terms of a Saudi-Houthi agreement first became public in January, when international media reported that Saudi Arabia had agreed in principle to pay outstanding civil servant salaries in Houthi-run areas, including those of military and security personnel, and to remove restrictions on entry points, including the ports of Hudaydah and Sana’a airport. In return, Saudi Arabia wanted guarantees that there would be no more attacks on its territory and the creation of a buffer zone along the border, an end to the Houthi blockade of southern ports and the siege of Taiz, and for direct Yemeni-Yemeni talks to follow any deal.

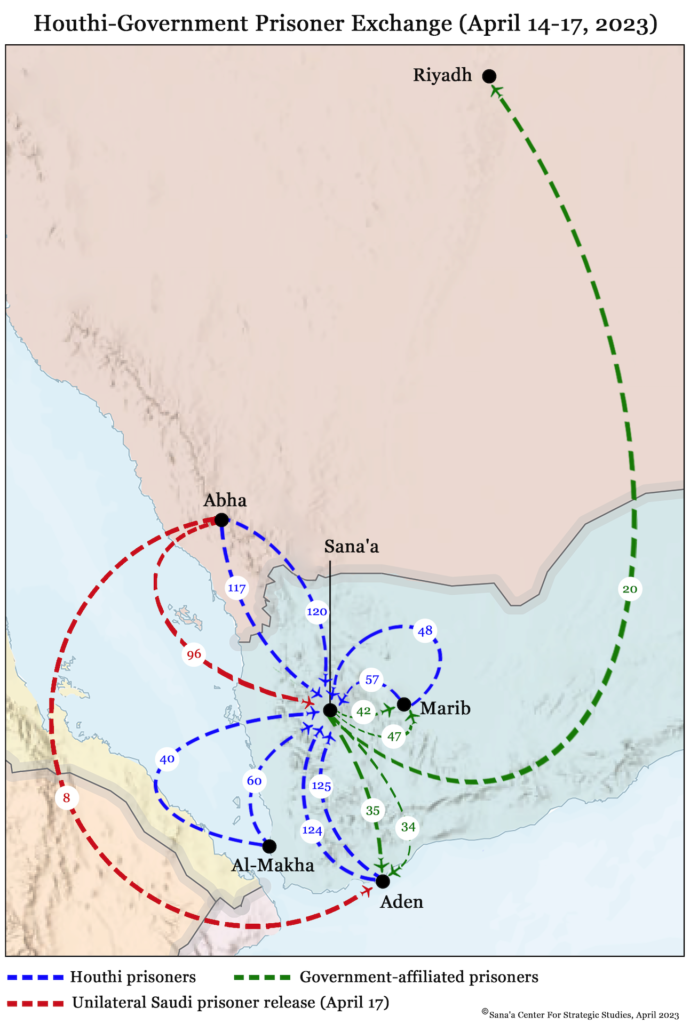

Within a few months, these proposals had morphed into a comprehensive roadmap for peace involving a six-month ceasefire, to be followed by three months of government-Houthi discussions on managing a transitional phase of two years, during which a final resolution of the conflict would be negotiated. A prisoner swap in April arranged by the International Committee of the Red Cross in Switzerland saw around 973 people released, including high-profile figures, and seemed to augur rapid progress. But Saudi Arabia appeared to overplay its hand when Ambassador to Yemen Mohammed al-Jaber led a delegation on a much-feted trip to Sana’a in April. The Houthis again raised their demands, arguing that an agreement must be signed first with Riyadh alone as a party to the conflict, and that Saudi Arabia should agree to pay compensation for war damage and finance postwar reconstruction. Al-Jaber left Sana’a without an agreement, but the basic terms of a formal de-escalation and path toward a resolution of the conflict were nevertheless laid down. Saudi Arabia’s problem now was how to manage resistance from the government’s Presidential Leadership Council (PLC). Ultimately, it was kept in the dark about the details of the proposed arrangement for most of the year, even its chairman Rashad al-Alimi, who was expected to sign off at the end of the process. A Houthi delegation met Saudi officials during a hajj pilgrimage trip in June – posing for photos with Defense Minister Khaled bin Salman – sending the signal that a formal agreement normalizing Saudi-Houthi ties and initiating a Yemeni-Yemeni peace process had become a question not of if, but when.

A complication that emerged early on was US reservations about a peace deal following the Saudi-Iran rapprochement brokered by China in March. This seemed to mark China’s arrival as a diplomatic player in the region, putting the Americans on notice that another global superpower was interested in challenging its role in the Middle East, including, perhaps, in Yemen. There was an irony here, in that rising criticism of Saudi Arabia’s conduct during the war in the US Congress, and threats to halt arms sales, played a role in bringing the Saudi leadership around the idea of getting out of Yemen and ending a foreign military adventure that had damaged its global standing.

Southern Trouble

The main challenge to the Saudi plan came from the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and its backer, the United Arab Emirates. Throughout the year, relations between the STC and Saudi Arabia were tense, and increasingly focused on the governorate of Hadramawt. Saudi Arabia began to deploy units of the Nation’s Shield forces – a Salafist-led militia placed under the control of PLC chief Al-Alimi – in governorates around Aden, giving the STC the sense that it was being hemmed in. At the same time, Saudi leaders relayed messages to the STC that any build-up of its armed forces in Hadramawt would trigger a direct Saudi military response. The STC then responded politically – reordering its governing body and issuing a national charter in May. Two surprise names were announced as deputy chairmen of the STC alongside Ahmed bin Breik: Faraj al-Bahsani, a current PLC member and former governor of Hadramawt, and PLC member Abdelrahman al-Mahrami, who heads the UAE-backed Giants Brigades. Other prominent southern figures were also brought on board, including Fadi Baoum, Ali Haitham al-Gharib, Abdelrauf Zayn al-Saqqaf, and Aiderous al-Yahri. The charter demanded that the southern issue have a special track established in the Saudi-Houthi roadmap, in order to give it “priority in the resolution.” It also said northern parties and forces should have no role in the formation of the southern negotiating body, that talks should take place in a foreign country, and that international actors, such as the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, the Arab League, the Gulf Cooperation Council, and the EU should act as witnesses to the final agreement. Following the announcements, the STC held its sixth national assembly in Mukalla on May 21, accompanied by a show of military force as military vehicles patrolled the streets.

Tensions increased over the summer as Saudi, US, and British diplomats signaled they felt that the STC was beginning to act as a state within a state. STC leader Aiderous al-Zubaidi, a member of the PLC, increasingly acted as an executive in his own right, facilitated in part by the STC’s control of the interim capital Aden. Concern over the STC’s assertiveness also revealed an underlying Saudi-UAE rift centered on Yemen, which international media soon began to pick up on. One report quoted Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman threatening to institute a Qatar-style boycott of the UAE. Saudi Arabia’s immediate response was to call Hadrami political, business, and social leaders to Riyadh for a conference in June, which led to the formation of the Hadramawt National Council as a rival to the STC-aligned groups in the governorate. Later that month, Al-Zubaidi traveled to the UK to press the argument that since a de facto Houthi state exists in the north, a revived southern one would be a natural complement. “The new reality is that the Houthis control the north and the STC governs in the south,” he said, adding that the south would be a state of “moderate nationalists” working with the international community. He had a chance to relay this message to the British government via a meeting with the British minister of state for the Middle East, Tariq Ahmad. During an appearance at Chatham House, a British think tank, he also talked respectfully of the need for coexistence with the Houthis as a “Yemeni Arab movement” that had succeeded in establishing their own state. After this, Al-Zubaidi reportedly had trouble obtaining a US visa for a similar publicity tour, but he was ultimately able to attend the UN General Assembly with Al-Alimi in September.

Gaza Gamechanger

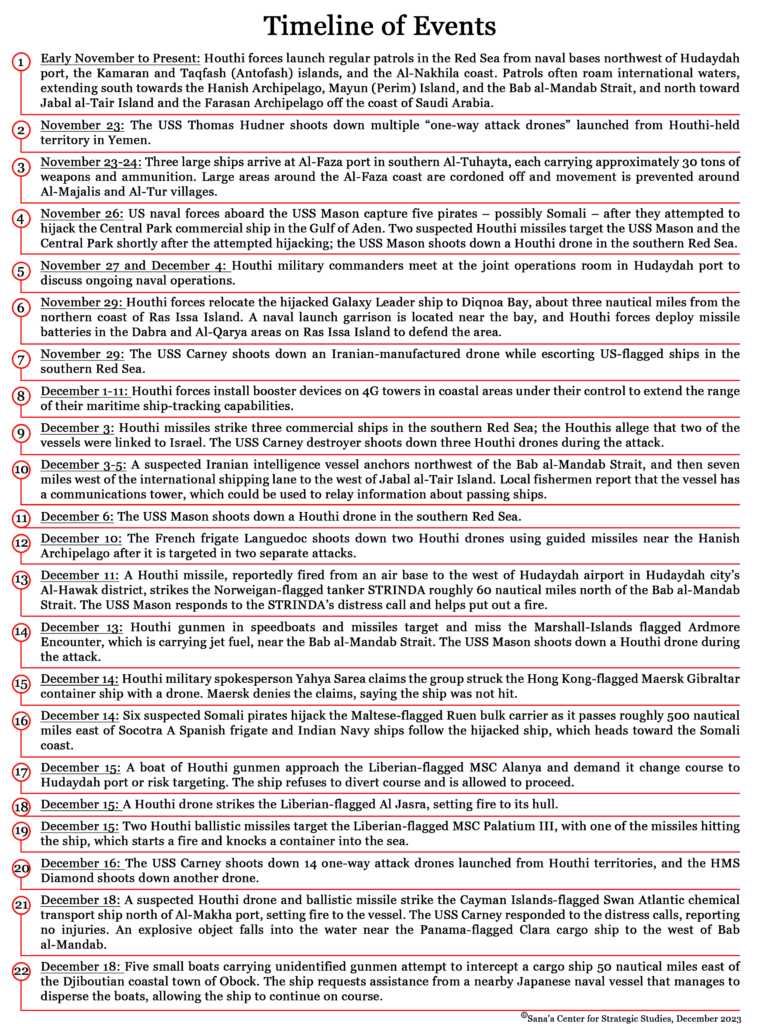

The October 7 Hamas attacks in Israel set in motion a chain of events that turned the Yemeni political scene upside down. The Israeli military campaign against Gaza, and the Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping in purported solidarity with the Palestinians, effectively brought the Saudi-Houthi peace talks to a standstill, returned the Houthis to pariah status in the West, and allowed the STC to cast itself as a responsible member of the anti-Houthi coalition. The crisis put Saudi Arabia in an awkward position as a US ally that opposed the disruption to global trade but was not willing to run afoul of the Houthis lest they begin targeting giga-projects that had spread down Saudi Arabia’s coast during two years of de-escalation. When the US and Britain began military strikes against Houthi targets in January 2024, Saudi Arabia issued a statement on the importance of ensuring safe maritime passage but expressing “great concern” over any acts making a tense regional situation even worse.

Seizing the opportunity to present the STC as a useful force against the Houthis, Al-Zubaidi appeared in January at the World Economic Forum in Davos, where he publicly criticized the harassment of Red Sea shipping, saying it had put a question mark over the nascent peace process in Yemen and hurt the economy. In an interview, Al-Zubaidi advised the US-British coalition to consider a ground operation against the Houthis – essentially reviving the war – that government forces could lead if the US would provide the arms, training, and intelligence. He added that the main lesson of the conflict is that airstrikes alone don’t work. The comments came in stark contrast to Al-Zubaidi’s earlier position when he tried to sell the idea of a division of Yemen into a Houthi north and STC-ruled south. PLC member Tareq Saleh and his UAE-backed National Resistance forces also became subjects of increased interest to the United States, as a frontline force facing off against the Houthis around the Bab al-Mandab Strait.

Military Maneuvers

Throughout 2023, Houthi forces boosted their presence along key frontlines in Taiz and Marib governorates but without major confrontation. The authorities in Sana’a also continued a litany of military parades, including a June march from Dhamar to Taiz that STC-aligned media denounced as a subterfuge for strengthening Houthi frontlines with thousands of extra soldiers. There were occasional incidents on the Saudi border in which Saudi-led coalition forces were killed – five Bahrainis died in September in what may have been hardliners within the Houthi leadership expressing opposition to the terms of a seemingly imminent Saudi-Houthi peace. But Saudi media for the most part kept quiet about such incidents in order to keep peace talks on track.

The major development on the security front during 2023, however, was the revival of Al-Qaeda in Yemen as a functioning, relevant force. This is partly due to the rising influence of Iran-based Egyptian operative Saif al-Adel, who is poised to become the official successor to Ayman al-Zawahiri as the overall emir of Al-Qaeda. His preference for attacks on Western, Saudi, and Emirati interests, and avoiding targeting Houthi forces, appears to dominate Al-Qaeda in Yemen’s current thinking. But a rift has emerged within Al-Qaeda in Yemen between leader Khaled Batarfi, who is Saudi, and a younger Yemeni group centered around Saad al-Awlaki. The dispute is reportedly over whether to follow Saif al-Adel’s approach or Al-Awlaki’s preference for targeting the Houthis.

On the ground, Al-Qaeda in Yemen has been far more effective. In May, the group carried out two drone attacks against the Shabwa Defense forces, the first time it had used such weapons. Al-Qaeda then managed to stage a series of attacks in Abyan that killed dozens of the STC’s Security Belt forces, including commander Abdellatif al-Sayed, indicating that the group was no longer confined to remote mountain hideouts. Al-Qaeda may have received large sums of money in exchange for the August release of the director of the UN Office of Security and Safety in Aden, Akam Sofyol, who was kidnapped in 2022 along with four Yemenis. Batarfi has spoken publicly about the need for financial support, asking southern tribes to help. When the Gaza conflict erupted, both Al-Qaeda and the Houthis began recruitment campaigns, though in each case the new fighters were intended for Yemen’s internal conflicts. For Al-Qaeda, its main enemies are still STC and US forces, and for the Houthis, the main battlegrounds are Marib, Taiz, and Al-Dhalea.

Tareq Saleh’s National Resistance forces have also boosted their status throughout the year. With Emirati funding they opened their own airport in Al-Mokha, which allows them to receive weapons directly. Tareq strengthened his position as a scion of the Saleh family, with ambitions to take leadership of the General People’s Congress (GPC), which he sees as the natural party of government. The party is currently split between anti-Houthi factions, with exiled members in regional capitals, and those working with the Houthi authorities in Sana’a. Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi appeared to sideline the latter when he announced a planned government reshuffle in September, in an apparent effort to reorder internal power dynamics ahead of a deal with Saudi Arabia and to respond to rising street protests over economic conditions. However, no further announcements came and plans to form a new cabinet in Sana’a appear to be on hold. But Saleh’s plan to use the GPC to vault himself into power has been a cause of tension with PLC chief Al-Alimi, who was a GPC member himself when he served in governments under Ali Abdullah Saleh. Throughout the year, Saleh has stood out for his strident anti-Houthi speeches, denouncing the Saudi-Houthi talks and vowing a return to Sana’a.

Economic Deterioration

The internationally recognized government flirted with bankruptcy for much of the year, as public sector revenues dried up and promised aid was postponed, exacerbating ongoing economic deterioration. The fiscal crisis began in October 2022, following the expiration of a UN-sanctioned truce. Houthi drones and missiles targeted southern oil terminals, effectively blocking the export of the government’s primary source of revenue and foreign currency.

Through its bilateral negotiations with Saudi Arabia, the Houthis secured the easing of inspections and other restrictions on goods imported through the ports of Hudaydah. Having done so, they began to block overland trade of imported goods, threatening traders that they must now direct their shipments through Houthi-controlled ports. On August 6, they formalized the arrangement by announcing additional taxes on all goods brought overland from government-controlled areas. The result has been a transfer of customs revenue from the government to Houthi authorities, which the CBY-Aden estimated could reach more than US$40 million a month. This was compounded by a further Houthi ban on domestically produced cooking gas, produced in government-held territory at the Safer facility in Marib.

The precipitous decline in oil, gas, and tax revenues in 2023 has produced enormous budget deficits and reduced the government’s capacity to cover essential expenditures. The August 2023 announcement of a new US$1.2 billion grant from Saudi Arabia provided a measure of relief, with the first tranche of US$267 million already released, but the vast public sector cannot subsist on irregular handouts, and private investment is limited by conflict and political fragmentation.

The government’s near-insolvency has led to repeated deterioration of the Yemeni rial in the territories it controls, and with the collapse of the electricity sector and the suspension of public sector salaries. By the end of the year, the central bank was no longer able to hold foreign currency auctions to support the value of the rial and finance the import of basic commodities, including foodstuffs. Absent the rejuvenation of revenue streams or massive, sustained external financial support, economic conditions will likely deteriorate further.

Electric Dreams

The shortage of electricity services in the south reached crisis proportions during 2023. The government’s falling revenues and the expiration of a Saudi fuel grant in April precipitated a collapse of the system. Although Yemenis living in Houthi-run territories are subject to many deprivations, a lack of electricity is not one of them – the system is mostly privatized, meaning that while electricity is expensive, at 234 Yemeni rials (YR) per kilowatt hour, it is at least available to those who can afford it in most urban areas. In Aden, things could not be more different. With the approach of summer, with its intense heat and humidity, life becomes almost unbearable for millions of people as rolling blackouts become longer and longer. Even in late October, residents of Aden were getting only two hours of electricity a day due to a shortage of fuel for power plants. The shortage persists despite massive subsidies to private sector suppliers of US$75 million to US$100 million a month, the largest government expenditure by far and double the public sector salary bill. The government uses this money – which usually comes from Saudi Arabia – to buy diesel, which is then given away for free to traders, who produce electricity from private generators and sell it back to the government for cut-price distribution.

The government’s fear is that removing subsidies, which keep the price at only YR12 per kilowatt hour for households when it’s available, will stoke public anger. It was mass protests against a hike in fuel prices that helped the Houthis to seize power in Sana’a in September 2014. A parliamentary report presented to the government of Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed in August described the electricity sector as a “black hole swallowing public money as a result of corruption.” The report stated that “it’s not a crisis of resources, it’s a crisis of managing resources.” Frustrated by the corruption, and determined to keep the PLC on a tight leash as the Houthi talks proceeded, the Saudi authorities withheld funding to the government for electricity, salaries, and other key budgetary matters throughout the year.

2023 Timeline

January

6: Sheikh Sadeq al-Ahmar, chief of the powerful Hashid tribal confederation, dies from cancer in Jordan at the age of 66. Al-Ahmar served as a member of the General People’s Congress during the rule of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, but also played a pivotal role in the 2011 uprising against him. Thousands of people, including dozens of important tribal leaders, attend his funeral in Sana’a.

17: Public reports reveal that the Saudi government is engaging Houthi representatives in backchannel talks with Omani mediators, as earlier reported by the Sana’a Center, in an effort to renew the UN-brokered truce.

29: Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) chief Rashad al-Alimi formally announces the formation of the Nation’s Shield forces, a Saudi-funded military force reporting directly to him. It consists of eight battalions led by Salafi commander Bashir al-Madrabi and started to deploy from Saudi Arabia to southern governorates in September 2022. Its members were reconstituted from some units of the Al-Yemen Al-Saeed brigades.

February

4: Al-Rayyan Airport, located in Hadramawt’s capital Mukalla, receives its first international civilian passenger flight in eight years, arriving from Jeddah. The airport was shuttered in 2016 and had been converted into a military base by Emirati forces.

5: A group of 25 influential women call on Houthi authority Prime Minister Abdelaziz bin Habtoor to end a series of policies that encourage gender discrimination, including mahram (guardianship) restrictions, segregation of women in official spaces, and discouraging girls from working and studying. A month prior, a well-known female broadcaster was arrested with two female colleagues for violating the mahram law. On February 12, a Houthi-run court upholds a five-year sentence for a female model and actress on allegations of violating public morality and carrying drugs. She is reportedly tortured in prison in Sana’a.

19: Saudi Arabia agrees to deposit US$1 billion into the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Aden as part of an agreement with the Arab Monetary Fund first announced in November 2022. The funds come as public revenues are plummeting due to the halt in hydrocarbon exports and falling customs revenues, following Houthi attacks on southern ports and pressure on importers to source goods via Hudaydah.

The Yemen Review January and February 2023: Saudi-Houthi Talks Sow Cracks in Coalition

March

2-17: Heavy clashes break out in southern Marib, with Houthi forces killing dozens of soldiers from the UAE-backed Saba Axis of the Giants Brigades. The Houthis advance and take strategic areas overlooking Harib district, including Jabal Buwara. Dozens of families are displaced due to the fighting.

10: Saudi Arabia and Iran agree to formally reestablish diplomatic relations for the first time in seven years in an agreement brokered by China, sparking hope among some observers that the deal could help bring the conflict in Yemen to an end.

21: Houthi authorities ban interest-based transactions in an effort to Islamize the Yemeni banking sector. The law, first drafted in September 2022, was reportedly pushed through by religious hardliners who refused to wait for a feasibility study.

23: Massive protests break out in Ibb at the funeral of social media activist Hamdi Abdelrazzaq, who died in Houthi custody. Following the demonstrations, Houthi authorities bring in a new security director for Al-Mashanah district in the Old City of Ibb.

25: Taiz Governor Nabil Shamsan survives an assassination attempt after his car is hit by an anti-tank missile and shelled in the Al-Kadha area in Al-Ma’afer district from Houthi-controlled areas overlooking the main road. A separate explosives-laden drone attack simultaneously targets the convoy of Minister of Defense Mohsen al-Daeri and Chief of Staff Saghir bin Aziz, who were traveling through Al-Wazi’yah district after attending a meeting with Shamsan and PLC member and National Resistance forces commander Tareq Saleh in Al-Makha.

The Yemen Review March 2023: Saudi-Houthi Talks Move Toward Ceasefire

April

4: Aden Governor Ahmad Lamlas announces an easing of import restrictions in the government-held port of Aden, allowing ships to sail directly to the port without stopping for inspection by the Saudi-led coalition. Hundreds of items are also removed from an embargo list. On April 8, the Blue Nile is the first ship to forgo the inspection process.

9: A delegation of Saudi and Omani negotiators arrives in Sana’a ahead of bilateral Saudi-Houthi talks. No agreement is signed, but both sides signal a willingness to move forward with a deal. Several days prior, Riyadh summoned the PLC to brief them on the deal, to which they are not a formal party.

14-17: The Saudis and Houthis exchange 973 detainees in a prisoner swap facilitated by the International Committee for the Red Cross. Among those released by the Houthis are the son and brother of PLC member Tareq Saleh, the brother of former president Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, a son and three relatives of former vice president Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, and four journalists previously sentenced to death. Following the swap, one of the journalists accuses the head of the Houthi National Committee for Prisoner Affairs, Abdelqader al-Murtada, of torture.

The Yemen Review April 2023: Saudis Visit Sana’a as Warring Parties Conduct Prisoner Exchange

May

5-17: After a series of meetings, Nation’s Shield forces assume control of the Al-Wadea crossing between Hadramawt and Saudi Arabia. In response, units of the UAE-backed, Southern Transitional Council (STC)-affiliated Shabwa Defense forces deploy on roads linking Shabwa to the crossing, giving them a strategic position from which to potentially cut off supplies or reinforcements.

8: The STC announces a major leadership reshuffle during its four-day-long Southern Consultative Meeting in Aden. STC chief Aiderous al-Zubaidi appoints three deputies: PLC members Faraj Al-Bahsani and Abdelrahman ‘Abu Zaraa’ al-Mahrami, and former Hadramawt governor Ahmed bin Breik.

21: The STC holds the sixth session of its National Assembly in Mukalla, coinciding with the 29th anniversary of the declaration of southern secession. Several influential Hadrami leaders pledge support for the STC during the event, including Ghalib Bin Saleh al-Quaiti, the last of the Al-Quaiti sultans of Hadramawt.

23: Houthi authorities ban the sale of domestically-produced cooking gas from Marib’s Safer plant, in favor of gas imported through the Houthi-held port of Hudaydah. This is a major blow to government revenues, as Safer is under government control. The first shipment of imported gas arrives in Hudaydah on July 6.

27-29: The evacuation of nearly 2,900 adult Yemenis from Sudan is completed following the outbreak of conflict in Khartoum.

The Yemen Review May 2023: A Southern Reshuffle

June

1: Houthi gunmen storm the Chamber of Commerce and Industry (CCI) in Sana’a and overthrow its leadership, following a dispute over price caps. Following the raid, Houthi authorities appoint loyalist Ali al-Hadi as head of the chamber, who has no background with the CCI or experience in commercial private sector activity.

12: Aden Governor Lamlas directs officials to stop paying revenues to the central bank in protest of a lack of services provided by the central government, namely electricity. Several STC-aligned governors follow suit, including Shabwa’s Awad bin al-Wazir al-Awlaki, and STC authorities use the dispute to push self-administration in the southern governorates. But Lamlas quickly falls in line and instructs that revenues again be directed to CBY-Aden.

17: CBY-Aden liquidates the second batch of funds from the International Monetary Fund Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), which come as part of US$665 million in SDR support announced in August 2021.

17: More than 270 Yemeni nationals fly from Sana’a to Saudi Arabia for the hajj pilgrimage, in the first such commercial flights in more than seven years. Among those traveling to Mecca are several Houthi leaders, including Yahya al-Razemi.

20: The Hadramawt National Council is formed in Riyadh, as a Saudi-backed entity intended to rival UAE- and STC-backed groups in the governorate. Following the announcement, PLC chief Al-Alimi travels to Hadramawt where he inaugurates dozens of development projects, coinciding with the announcement of US$320 million in Saudi funding.

20: Houthi forces increase naval patrols off the coast of Hudaydah, with boats crossing into the international shipping lanes and approaching ships near Al-Salif port and Kamaran Island.

July

18: The government-aligned House of Representatives objects to the sale of the state-run internet service, Aden Net, to the Emirati-owned NX Digital Technology company. Despite the objection, the government later approves the establishment of a joint telecommunications company with NX Group.

21: Jordanian national Moayed Hameidi, the head of the World Food Programme (WFP) in Taiz governorate, is assassinated in Al-Turbah, near the southern border with Lahj. Security services arrest more than 20 suspects, claiming many have ties to Al-Qaeda, and the group responds by threatening local authorities in Taiz. An investigator working on Hamdeidi’s case is later killed after receiving death threats.

27: The WFP announces it will suspend malnutrition prevention services in Yemen as early as August. Officials insist that the decision is driven by a lack of funding and not political or security considerations, citing warnings made as early as January 2022.

The Yemen Review June and July 2023: Temperatures, Tensions Roil Government

August

1: Saudi Arabia announces US$1.2 billion in new funding for the internationally recognized government, in an attempt to finance the public budget and support the Yemeni rial. The following day, the first tranche of nearly US$267 million is received by the CBY-Aden.

2: Government officials move to transfer public salaries through commercial banks, rather than via money exchange companies, justifying the move as an attempt to limit corruption. The decision is met with harsh criticism in the following months, with protests erupting across government-held territories.

6: Security services in Abyan’s Mudiya district launch Operation Swords of Haws, a counterterrorism operation designed to complement Operation Arrows of the East. The campaign is undertaken by STC-affiliated Security Belt forces, Abyan Military Axis forces, Support and Backup Brigades, and local security and pro-government forces. The operation has relative success in securing sites around the Omayran Valley.

11: Five UN employees kidnapped by Al-Qaeda in Abyan in February 2022 are released after 18 months in captivity.

13: Giants Brigade forces loyal to PLC member Al-Mahrami raid the Maashiq Presidential Palace in an attempt to confront Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed. Details of the incident are murky and Giants Brigades-affiliated media deny it altogether, insisting the forces were simply following up on security issues.

17: An Omani delegation accompanied by four Saudi negotiators and two Iranian diplomats arrives in Sana’a at the request of the Houthi negotiating team to continue bilateral discussions. In the preceding days, a flurry of diplomatic activity occurs between PLC members, US Special Envoy Tim Lenderking, and UN Special Envoy Hans Grundberg, with the latter briefing the UN Security Council.

20: Nearly 80 percent of public and private-owned power stations in government-held territories shut down due to lack of fuel. Throughout the summer, cities across the country experience major blackouts, with electricity available for only a few hours a day in some governorates. Despite government attempts to import fuel through the port of Aden, widespread protests break out. The provision of electricity remains unstable, with warnings of a complete electrical grid shutdown repeated again in late October.

25: The government-aligned House of Representatives issues a report detailing alleged corruption across multiple public institutions, following an investigation of the government’s decision to approve the sale of Aden Net to NX Digital Technology. Prime Minister Saeed denies the allegations.

28: Two Doctors Without Borders (MSF) employees are kidnapped in Marib by unidentified gunmen while traveling from Hadramawt’s Seyoun city.

29: The United Nations completes the transfer of over 1.14 million barrels of oil from the decrepit FSO Safer tanker, which has been moored off the coast of Hudaydah for years. The operation takes nearly a month and involves transferring the oil to the Yemen, a replacement ship under Houthi control.

The Yemen Review August 2023: Saudi-Houthi Talks Resume

September

14: A Houthi delegation led by Mohammed Abdelsalam arrives in Riyadh for the first time since the outbreak of the conflict, meeting with Saudi Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman over five days of talks. The Saudi government subsequently announces it is preparing a roadmap for peace in Yemen.

25: A Houthi drone strike near the Saudi-Yemen border kills five Bahraini soldiers serving as part of the Saudi-led coalition, in the first acknowledged fighting between the two sides since a UN-brokered truce was signed in April 2022.

21: Houthi forces stage a military display in Sana’a on the 9th anniversary of the group’s takeover of the capital. Replicas of Iranian missiles and drones are displayed during the event alongside thousands of soldiers, and an F-5 fighter jet flies overhead for the first time during the war.

26: Houthi security forces arrest hundreds of civilians in Sana’a for celebrating Revolution Day, which commemorates the overthrow of the Zaidi imamate. Viral videos emerge of Houthis damaging cars and beating people waving the republican flag, and dozens of people, including women, are held in prolonged detention.

October

1: Yemenia Airlines suspends commercial flights from Sana’a to Jordan following a dispute with Houthi officials over company funds held in a Sana’a-based bank, closing the only route out of Sana’a. Flights resume on October 17 for humanitarian reasons, despite continued Houthi efforts to block the funds’ disbursement.

7: Hamas launches surprise attacks on southern Israel, leaving hundreds dead and taking hostages back to Gaza. In the following days, Israeli forces initiate a military campaign in the Gaza Strip, sparking outcry from both the Yemeni government and the Houthis.

8: Houthi intelligence arrests Abu Zaid al-Kumaim, head of the Yemeni Teachers Club, for organizing protests demanding the payment of teachers’ salaries.

10: Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi publicly threatens Israel. On October 19, the USS Carney intercepts four Houthi missiles and drones over the Red Sea, the first attempted Houthi strikes since the outbreak of the Gaza conflict. The group subsequently claims four separate attacks targeting the Israeli port of Eilat.

23-24: Cyclone Tej brings torrential rainfall and heavy winds to parts of Yemen, resulting in loss of life, displacement, and infrastructure damage. Over 41,000 people are impacted by the destruction caused by the storm, with thousands displaced and hundreds of homes and roads destroyed across multiple districts.

24: At least four Saudi soldiers are killed in clashes with Houthi fighters near the border between Saudi Arabia’s Jizan district and Yemen’s Hajjah governorate, following a Houthi attempt to destroy new surveillance cameras near the border.

26: Save the Children announces the death of its Security and Safety Director for Yemen, Hisham al-Hakimi, who reportedly died in a Houthi prison after being forcibly disappeared a month prior. The group suspends activities in Yemen, resuming work on November 7.

The Yemen Review September and October 2023: Houthis Target Israel Amid Gaza Conflict

November

7: Army Chief of Staff Saghir bin Aziz survives an assassination attempt in Marib’s Wadi Abidah district after meeting with Marib Governor and PLC member Sultan al-Aradah. Government officials blame the Houthis for the attack. At the same time, Houthi forces launch a major offensive along the Al-Kasara front northwest of Marib city, killing at least eight pro-government soldiers.

9: Houthi forces shoot down an American MQ-9 drone over the Red Sea on grounds that it was operating in Houthi airspace. US defense officials deny the claim.

19: The Houthis hijack the Galaxy Leader, a Japanese-operated cargo ship with links to a wealthy Israeli businessman. In the following weeks, the ship and its crew are held hostage as Houthi naval forces relocate the vessel several times. The ship is made into a major tourist attraction, with dozens of civilians posting trips to the deck on social media.

26: Hadramawt Governor Mabkhout bin Madi directs local officials to stop sending revenues to the central bank, similar to the protest staged by Aden Governor Lamlas in June.

28: The presidium of the Hadramawt National Council is announced nearly six months after the council’s formation in June. Following the statement, PLC chief Al-Alimi meets its 23 members in Riyadh.

30: Yemen participates in COP28 with a delegation led by PLC chief Al-Alimi. An agreement is made with key private sector actors to act as intermediary parties for climate finance.

December

5: The WFP suspends food distribution in Houthi-controlled territories due to a lack of funding and interference by Houthi officials. Humanitarian and non-governmental organizations criticize the decision, arguing that up to 9.5 million people will be affected in northern Yemen.

7: The US Treasury sanctions 13 individuals and entities associated with the Houthis via a financial facilitator known as Sa’id al-Jamal.

9: Following an intense period of Houthi attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea with multiple ships being hit, Houthi naval forces begin targeting all ships sailing to Israel, regardless of ownership. In the following days, dozens of major international shipping companies reroute in order to avoid passing through the Red Sea.

19: The White House formally launches Operation Prosperity Guardian, a coalition of over 20 countries aimed at defending ships in the Red Sea from Houthi attack. This entity is distinct from the coalition led by the US and UK which will repeatedly strike Houthi targets in Yemen in 2024.

23: The Office of the UN Special Envoy for Yemen announces plans to establish a UN roadmap for peace after talks with the PLC in Riyadh and the Houthis in Muscat. The proposal will largely be based on direct Saudi-Houthi talks mediated by Oman.

The Yemen Review November and December 2023: The Red Sea Front

Yemen in 2024: Sana’a Center Experts Look Ahead

The Yemeni State in 2024

2023 started with high, albeit totally misplaced, optimism regarding a peace agreement between the warring parties in Yemen. In late 2022, Saudi Arabia initiated peace overtures toward the Houthi group (Ansar Allah). By April 2023, a Saudi delegation led by Ambassador Mohamed Saeed al-Jaber was in Sana’a, exchanging warm hugs and smiles with Houthi leaders. After further talks, including a well-publicized visit by a Houthi delegation led by Mohamed Abdelsalam to Riyadh, received with pomp and circumstance and a meeting with Defense Minister Prince Khaled bin Salman, preparations began for the internationally recognized government and the Houthis to sign a roadmap for peace, which would include payment of public sector salaries for one year, organize a transitional power-sharing arrangement, and begin a two-year transitional period during which a political dialogue would settle the details of state structure and the final status of the south. This was to be followed by national elections. But the roadmap left the boundaries of such a political agreement open and did not stipulate building on what was agreed at the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) in 2013-14, such as the adoption of decentralization or limiting the size of the active armed forces to 1-1.5 percent of the total population. The plan was, in effect, leading to no place in particular; a roadmap to nowhere.

It was a formula for failure for three key reasons. The first is that it ignores Yemen’s cumulative political heritage of coexistence, accommodation, and consensus-building, leaving the door open for divisive issues to be mobilized again. Relinquishing the few, precious successes of the NDC invites unnecessary instability that could fracture the Yemeni state.

The second is the short time frame. Yemen is so divided that bringing it back together will take time. Restructuring the state is now a prerequisite to national elections. While the Houthis have maintained and further centralized the simple state model that existed under the rule of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, the model has fractured in the areas nominally under the control of the internationally recognized government. Local governments have assumed the competencies of the central government on an ad hoc basis, but also in the spirit of the NDC, which responded to the popular demands of greater local autonomy. The two-year transition period was also too short to implement the outcomes of the NDC. Now, with a fractured state and warring factions dominating the scene, carrying out another, more complex transition in two years is an impossible mission.

These two challenges are amplified by a third divisive issue: the imbalance between the two sides of the conflict. While the Houthis enjoy a strong unified leadership and have control over central state institutions that were built over decades, the internationally recognized government has neither unity of leadership nor the institutional capacity to govern. Negotiations between these two sides, with such an imbalance in favor of the Houthis, make it impossible to reach a balanced and equitable power-sharing arrangement.

The most likely scenario of peace negotiations under these circumstances is that the Houthis will offer no concessions, and negotiations will drag on for years, during which the internationally recognized government will slowly falter under the pressure of its own divisions. The Houthis will win at the negotiation table what they could not win on the battlefield: a total victory. The Houthis will become the dominant power in Yemen, but it is inconceivable that the South, Taiz, or Marib will agree to surrender to the harsh conditions of Houthi control. The Yemeni state will disintegrate into the respective fiefdoms of armed groups.

Southern ambitions of restoring their state, or Houthi ambitions of having their own Zaidi, Taliban-style country are unrealistic, given that before 2011 Yemen was already teetering on the edge of state failure due to massive demographic pressure, lack of human capital, over-militarization, festering corruption, eroding regime legitimacy, and massive environmental challenges, including the worst water poverty in the world. Since then, these challenges have gotten worse, and are compounded by the conflict among the parties and their need to arm and prepare to fight each other. All indications lead to one conclusion. Yemen is on its way to Somaliazation, with the caveat that Somalia has already adjusted to its fragmentation. Yemen will be much worse than what Somalia is today.

The Gaza war and conflict in the Red Sea may have changed that scary trajectory. In solidarity with the Palestinian people of Gaza, the Houthis have enforced a blockade on ships destined to or otherwise linked with Israel. This military action serves as a clear example that, in the absence of an inclusive peace and equitable and balanced political settlement, there will be no check on the militancy of the most extreme faction of the Houthi group, and no guarantee that marine traffic through Bab al-Mandab will not be disrupted again. Regional and international actors are now coming to accept the basic fact that only an inclusive peace in a unified Yemen can guarantee the long-term stability of the Red Sea. The Houthis’ actions have gripped the attention of the world and may ultimately force the group to curb its excessive ambitions, saving themselves from themselves.

The Economic Outlook in 2024

Yemen’s economic situation in 2024 remains deeply concerning, marked by the devastating effects of a protracted conflict, a fragile truce, and ongoing humanitarian needs. Developments in the Red Sea threaten to deepen Yemen’s economic woes and weaken prospects for peace. Recent military confrontations, culminating in Houthi attacks on international shipping, have sent ripples through the global economy, disrupting vital trade routes and raising concerns about energy security and supply chain resilience. The situation is still evolving, and its full economic impact is difficult to predict. The long-term effects will depend on how quickly the situation is resolved and what measures are taken to ensure the safety of shipping. International cooperation and diplomatic efforts are crucial to de-escalate the situation and prevent further economic harm.

For Yemen, the Houthi attacks on international shipping could throttle its already fragile economic lifelines, pushing the war-torn nation toward catastrophic collapse. In the case of escalated conflict, port closures become a possibility, which would cause significant disruptions to shipments and trade, leading to losses and higher costs. Over 90 percent of Yemen’s essential imports, including food, fuel, and medical supplies, traverse the Red Sea. Disruptions cripple trade flows, pushing basic necessities beyond the reach of millions. In the light of ongoing military confrontations, marine shipping and insurance costs for goods arriving at the ports of Hudaydah have been rising. Ultimately, these increased costs are likely to be passed on to consumers, further exacerbating the already dire humanitarian situation.

The recent designation of the Houthis as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGT) by the US, scheduled to come into effect on February 16, also carries economic implications. While the intended goal is to pressure the Houthis to cease their attacks and engage in peace talks, the economic consequences are multifaceted and potentially counterproductive. US sanctions will restrict financial transactions with the Houthis and individuals and entities associated with them. Aid organizations undertaking distribution in Houthi-controlled areas may face difficulties, potentially impacting millions in need. Businesses and individuals engaged in trade with Houthi-controlled areas could face legal and financial challenges. Disruptions to trade and aid could exacerbate food shortages and malnutrition, especially in Houthi-held areas. The existing economic divide between Houthi- and government-controlled areas may widen, hindering future reunification efforts. Increased risk and uncertainty continue to deter foreign investment crucial for Yemen’s recovery. While sanctions may not significantly affect core Houthi funding, they add further strain on their ability to provide basic services.

The Houthis may perceive the designation as an escalation, leading to increased attacks and further hindering economic activity. Heightened tensions with Iran could also impact regional trade and investment flows. The long-term impact on the Yemeni population, already facing immense hardship, remains a major concern. The international community’s response to the designation and its effectiveness in mitigating negative impacts are factors to be monitored.

Existing challenges also pose continued risks. The suspension of oil exports since the Houthi military attacks on oil exporting port infrastructure in late 2022 will likely continue, shrinking government revenues and exacerbating the fiscal crisis. Depleted foreign reserves limit Yemen’s ability to import essential goods and stabilize the currency. Disruptions to port activities and export limitations stifle economic activity, depriving Yemen of crucial revenue needed for basic services and reconstruction.

The future remains precarious. Renewed violence or the complete collapse of the truce could erase fragile gains and worsen the crisis. However, sustained peace efforts, increased international aid, and economic reforms could unlock latent potential. Rebuilding infrastructure and essential services would create jobs and stimulate growth. Creating a stable environment could attract investment, boosting key sectors like agriculture. Sustained aid is crucial to address immediate needs and support long-term development. However, without a lasting peace agreement, economic recovery remains elusive.

Environment and Water in 2024

The current situation in Yemen presents both challenges and opportunities relating to water security, environmental sustainability, and climate resilience. In the coming year, these issues must be placed at the forefront of political discussions. Several areas require close attention to help integrate these considerations into future plans and policies.

Shortages in freshwater resources are expected to escalate due to war, climate change, demand increase, and poor management. Local water disputes, long a part of Yemen’s history, could also escalate if not properly managed. Cooperation among local authorities, UN bodies, and mediators might help mitigate conflicts and build trust between the opposing sides, especially in Taiz. Community-level experience in mediation and lessons from past resolution of water-related conflicts should be studied and replicated where possible.

As the impacts of climate change intensify, strengthening Yemen’s ability to adapt critical infrastructure, agricultural systems, and flood management measures should be a priority this year. Ensuring a just transition on environmental and climate questions will help avoid disproportionate impacts on vulnerable regions and communities. Research by Columbia University on climate justice frameworks could be helpful for national strategies and discussions conducted by policymakers and international partners.

Yemen also needs help accessing global funds earmarked for climate resilience projects. It must engage international financial institutions and solicit their support for the development and implementation of national adaptation plans. Such programs must be implemented through a climate justice lens that empowers marginalized groups and favors just transition policies. Traditional coping strategies and innovations from similar contexts should be investigated to ensure adaptation works on a local level. Egypt and Morocco’s climate financing models could provide useful insights for Yemen.

Lastly, the current conflict in the Red Sea seems likely to harm the livelihoods of fishermen and the security of marine life. What environmental effects might there be if warfare escalates, or if a military ship or oil tanker is bombed? Monitoring and documenting the potential impacts of such scenarios will help raise awareness and provide timely data to concerned stakeholders.

The Houthis in 2024

2024 marks a watershed for both the Houthi group (Ansar Allah) and Yemen. The growth of the Houthis’ military capabilities and its emergence as the self-proclaimed defender of Palestinians through its attacks in the Red Sea were not foreseen by most observers. But these developments have far-reaching consequences, perhaps most notably threatening to derail the peace process between the group and Saudi Arabia.

Domestically, the Houthis will attempt to capitalize on the popularity gained through their attacks in the Red Sea, which give credence to their slogan depicting America and Israel as their main enemies. The US-UK strikes have cast the group as national heroes being targeted for standing with the people of Gaza – a sensitive issue that strikes a chord worldwide, particularly in Arab and Muslim countries. But a decade of bombardment by the Saudi-led coalition has left few targets to hit. Hence, the recent strikes have so far had limited military effect on the Houthis, but bolster its claim to be a staunch defender of Palestine.

Their newfound momentum has not only allowed the Houthis to circumvent the popular discontent that has been escalating over the last two years due to unpaid public sector salaries (which had prompted the group to crack down on dissent); it has seen their popularity surge to the extent that their critics now stand accused of being agents of the US and Israel.

On the other side, the internationally recognized government is growing weaker by the day, as the economy and security sector collapse. This may push the Houthis to make the most of the opportunity to mobilize newly recruited fighters, establishing popular forces like those in Amran governorate and moving them to frontlines in Marib, Shabwa, the west coast, and Taiz.

From the Houthis’ point of view, these developments help it position itself as the party most capable of defending the sovereignty of Yemen. The group may push to take control of oil fields in the east; should it succeed, it could seek to expand further, especially if the Saudis maintain their current neutrality. Saudi Arabia is keen to end its war with the Houthis and strike a deal, even if that means sidelining its allies in the Yemeni government.

The Houthis may assent to Saudi Arabia’s core demand – security of its border – in exchange for greater domestic clout. However, such an arrangement would be threatened by direct Western intervention to remove the Houthis. This is currently unlikely, as the participation of local forces would cast them as agents of the US and Israel in the eyes of many Yemenis. The only development likely to change the current situation is an end to the Israeli offensive in Gaza.

The key issue remains how far the US will go to deter the Houthis, weaken their power, and prevent their rearmament. This could also impact the terms and likelihood of a Houthi agreement with Riyadh. In regional and international calculations, it is impossible to discuss a settlement with the Houthis without taking the interests of its Iranian backers into consideration, despite the relative independence the group claims to enjoy in local decision-making. The Houthis have been Iran’s most visible ally of late, and Western engagement with Tehran could be a key determinant of the Houthis’ actions in the Red Sea, on the Saudi border, or against US interests in the Gulf.

Unless the balance of power changes on the ground, Houthi control could expand beyond its current borders in 2024. Military gains could in turn lead the Houthis to change their approach towards Riyadh and the region. If, on the other hand, international actors escalate further in an effort to degrade the group’s capabilities, the Houthis could still return to war. For them, conflict is a means of political survival, not simply a policy choice.

The International View on Yemen in 2024

Few observers of Yemeni politics could have imagined that the year would end in such a manner. 2023 began with negotiations between Saudi Arabia and the Houthi group (Ansar Allah) to end Saudi involvement in the war. It ended with the Houthis attacking Red Sea shipping and a US-led military escalation that changed the trajectory of the conflict and placed a question mark over any peace settlement.

When he became president in 2021, Joe Biden said ending the war in Yemen was a foreign policy priority, and removed the designation of the Houthis as a terrorist group. Now, he approaches the end of his term by striking Houthi military targets and redesignating the Houthis as a terrorist organization. The US and Britain now lead a coalition to counter Houthi attacks on Red Sea trade.

Both countries cooperated in the past to target Al-Qaeda in Yemen, but in recent years they have begun to rely more on regional powers for counterterrorism efforts, such as the UAE, and their political approach has tended to align with that of Saudi Arabia. The US and UK initially supported the Saudi-led war in Yemen but put pressure on Saudi and Emirati forces to halt their advance up the western coast in 2018, following the outcry over the murder of Jamal Khashoggi and concerns that an assault on Hudaydah city would escalate an already dire humanitarian crisis. Perhaps tired of bad press, the Saudis became determined to end their involvement in the Yemeni war and rebrand as a luxury tourist destination and investment hub. This required an end to Houthi missile attacks on Saudi targets.

During 2023, Saudi Arabia and the Houthis were close to striking a deal to end hostilities between them. Leaks showed that the Houthis were finding acceptance of most of their demands in return for vague security promises, while other Yemeni parties who had been supported by Saudi Arabia and the UAE were sidelined. The Gaza war changed these political calculations. The Red Sea attacks have raised the profile of the Houthis in Western eyes, and they are now perceived as an active regional power, part of the Iran-led “Axis of Resistance,” and a threat to global shipping. Before the attacks, the US and UK appeared relatively unconcerned about the Houthis as the de facto authority in north and west Yemen or the potential expansion of their territory following a deal with Saudi Arabia.

The Houthis have their own mini-state in north Yemen with independent financial resources through a large taxation base, consisting of some 20 million people. Yet their unpopularity in areas under their control is rising as they rely heavily on oppression to impose their authority and follow a policy of divide and rule to maintain control of a complex society.

It’s impossible to predict what’s coming next. The Gaza war could expand to new, surprising localities, or alarm in the Biden administration over the state of regional disintegration could finally spur the US to act to restore calm. But what is clear is that the role of the Houthis has changed, from a local Yemeni group to a regional player. This risks turning Yemen into an international battleground and postponing the possibility of a peace agreement that just a few months ago was seen as almost inevitable.

Southern Yemen in 2024

The year 2023 was an eventful one, with many dramatic developments, from the revival of ambitious peace talks (the draft roadmap for Yemen, Saudi-Iranian rapprochement, and the progress of Saudi-Israeli normalization talks), to unprecedented escalation following Hamas’ Operation Al-Aqsa Flood attack in October. Throughout this regional volatility and its domestic reverberations, southern Yemen has been a key element.

In the first half of 2023, the status of the south emerged as a critical issue, exposing the limitations of a Saudi-led peace initiative subsequently adopted by the UN Special Envoy’s office and referred to in the media as the “roadmap.” Southern Yemen was the scene of repeated episodes of escalation by the Southern Transitional Council (STC), which aimed to improve its negotiating terms. These were met by escalatory moves from the Saudis and their local allies, with polarization peaking in Hadramawt during May and June.

However, the regional and international community re-assessed its position toward southern Yemen during the last quarter of 2023, following the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, one of the most important international maritime trade routes. Supporting the forces responsible for protecting Yemen’s southern and western coasts has now become an important consideration in securing the region. Against this backdrop, the international community has intensified its coordination with members of the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), especially the STC.

Polarization will likely continue in Southern Yemen due to two opposing dynamics. On the one hand, it could become a ticking time bomb for the sponsors of any hasty peace agreement with the Houthis. On the other hand, it could become an important actor whose capabilities are strengthened to provide deterrence against Iran’s destabilizing behavior in the Red Sea, the Bab al-Mandab Strait, and the Gulf of Aden. Developments in the first quarter of 2024 favor the second dynamic, seeing the South receiving support as a geopolitical actor, rather than a political dilemma. But this will not prevent political polarization, given the series of threats that feed existing tensions.

The first threat is the widespread economic collapse taking place amid the declining value of the Yemeni rial, the economic repercussions of the Houthi escalation in the Red Sea, and the severe financial hardship that the government has been facing following the suspension of oil exports in late 2022. As is usual during the hot summer months, southern governorates witnessed popular protests in 2023. This year, the protests began early as residents of Aden struggle with the almost total disruption of services even before the end of cooler winter months. This has put pressure on the STC leadership and may make it inclined to adopt an escalatory approach to assuage its disgruntled base.

The second threat is the continued geopolitical rivalry between Saudi Arabia and UAE playing out in Yemen, especially in Hadramawt. While Riyadh continues to empower the Nation’s Shield forces, the UAE is supporting loyal military forces in the 2nd Military Region and encouraging their wider deployment in Wadi Hadramawt as a challenge to the Islah-affiliated 1st Military Region based in Seyoun. The persistence of this competition will likely lead to new rounds of political escalation.

The last threat comes from the political and social consequences of returning to a peace process without improving the terms of the proposed settlement in a way that guarantees broader inclusiveness or a real balance of interests, and without providing meaningful guarantees on the southern issue. The Saudi-Houthi talks have been dangerously exclusive and may sow the seeds of further discord.

With these ongoing challenges, the situation in southern Yemen appears increasingly fragile and volatile and could explode at any time. There are a number of variables that may emerge as a result of conflict dynamics that could reshape conditions in southern Yemen into a more consolidated and stable environment. But overall, these dynamics are dependent on the Houthis’ rogue behavior and how determined they are to threaten local and international actors.

Deepening the Houthis’ isolation and imposing sanctions will create an opportunity to divert regional and international support – especially economic and humanitarian support – to Aden and other southern governorates. This would slow the pace of economic decline in southern Yemen. The keenness of international and regional partners to adjust the strategic balance of power in Yemen to fight the Houthis will require strengthening Aden’s role as the capital and center for political and legal decision-making. Political support could be directed to help reduce polarization in the government camp. International actors could also seek to influence events through direct military support. If the various military forces affiliated with the government were to redirect their attention north toward confronting the Houthis, the risk of internal conflict in the south would be reduced.

At the local level, a number of recent indicators have emerged that reflect PLC’s desire to develop common understandings to address the deteriorating situation in the government-held areas and to strengthen its capacity to fight the Houthis. One is the formation of a unified intelligence service and a special security apparatus to combat terrorism, as well as the appointment of a new prime minister. If these moves become a part of a broader effort to build political consensus and restructure the state apparatus, it could enhance stability in southern Yemen in the coming period.

The Yemeni Government in 2024

Unlike the start of 2023, Yemen entered 2024 in tumultuous circumstances in light of the stand-off between Western countries and the Houthis over the threat to Red Sea shipping. As a result, the Yemen war was no longer limited to the regional parties but had become an issue of global concern. Consequently, the world will witness more economic and political pressures as a result of the escalation in the Red Sea. This creates new challenges for Yemen’s internationally recognized government.

After months of speculation, Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed was replaced by Foreign Minister Ahmed Awadh bin Mubarak in early February, in a move that appears to be technically unconstitutional since it was not accompanied by any cabinet reshuffle and was done without parliamentary approval. Bin Mubarak has been close to Saudi Arabia in the past, but he does not have a close relationship with Riyadh-backed Presidential Leadership Council chief Rashad al-Alimi. He is also a problematic figure for the UAE’s allies, especially the STC, despite being a southerner, which will certainly complicate his task of leading the government.

The Houthi escalation has strengthened UAE-backed components of the government such as Tareq Saleh and his National Resistance forces, and the Giants Brigades. If there is a ground operation to confront the Houthis – a distant possibility for now – it will depend on these forces based on the Red Sea coast, instantly restoring depleted Emirati influence in Yemen.

Divisions within the PLC remain deep, reflecting disagreements between Saudi Arabia and the UAE over how to deal with the Houthis. For now, Al-Alimi is able to benefit from these political and personal disputes to maintain his influence and hold the PLC together under his leadership, despite the fact that he is not backed by a major military force or a strong party like the rest of the PLC members. One of the council’s purposes is to provide a rubber stamp for the Saudi-Houthi peace deal, if it comes, and manage members’ divergent interests (whether personal or reflective of their regional backers. Al-Alimi’s chairmanship of this heterogeneous council remains a very difficult task.

This issue of the Annual Yemen Review was prepared by (in alphabetical order): Musaed Aklan, Murad Al-Arefi, Ryan Bailey, William Clough, Casey Coombs, Yasmeen Al-Eryani, Tawfeek Al-Ganad, Hamza Al-Hammadi, Andrew Hammond, Khadiga Hashem, Abdulghani Al-Iryani, Yazeed Al-Jeddawy, Maged Al-Madhaji, Elham Omar, Hussam Radman, Ghaidaa Al-Rashidy, Miriam Saleh, Maysaa Shuja Al-Deen, Lara Uhlenhaut, Ned Whalley, and the Sana’a Center Economic Unit.

The Yemen Annual Review 2023 is part of a series of publications produced by the Sana’a Center and funded by the government of the Kingdom of The Netherlands. The series explores issues within economic, political, and environmental themes, aiming to inform discussion and policymaking related to Yemen that foster sustainable peace. Views expressed within should not be construed as representing the Sana’a Center or the Dutch government.