“Eventually, it should all go back to Yemen.”

Yemen has been at the heart of Helen Lackner’s life for more than half a century. A distinguished and prolific author and non-resident fellow at the Sana’a Center, Lackner has covered topics as diverse as climate change, economic collapse, women’s role in society, and the historical roots of the ongoing conflict. The depth and breadth of her work have made her a respected and authoritative voice on Yemen for many years.

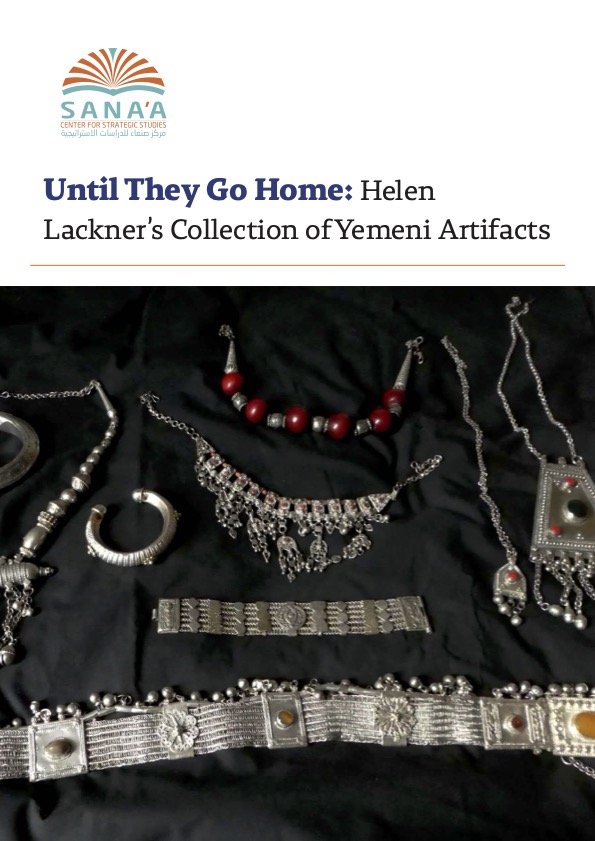

Lackner first visited Yemen in 1973, and in 1977, went to teach in the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), or South Yemen. She later moved to the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR), or North Yemen, and, over the following five decades, spent about 15 years working in Yemen, witnessing its many political transformations. During this time, Lackner worked in teaching and research and carried out development work with rural communities, focused on agriculture and fisheries. While living in Yemen, Lackner also built an impressive collection of Yemeni artifacts, including miniature models of Yemeni buildings, unbaked mud pottery, dresses, jewelry, basketry, and woodwork, bought from across the country. In June 2025, Mabrouklyn hosted an exhibition featuring around 60 pieces from Lackner’s vast collection of around 500 artifacts at the Kunstraum Gallery in London, offering the public a rare glimpse of Yemen beyond the backdrop of war.

For this edition of the Yemen Review, Lackner spoke with Sana’a Center editor Lara Uhlenhaut about why she treasures this important collection and why she wants to preserve it until it returns to its original home.

Lara Uhlenhaut: Helen, what first brought you to Yemen?

Helen Lackner: I first visited Yemen in 1973 and later sought to spend time in the region to learn Arabic. I got a job teaching in South Yemen through the PDRY embassy. I didn’t particularly want to teach, but I ended up teaching English and French at secondary schools and universities in Aden and Abyan. I was one of the few foreigners working for the PDRY government on a government salary, earning less than I could have received here in England on social security benefits. Most recognized voices on Yemen, such as Sheila Carapico, went to the YAR, and many did so because they could not complete their PhD fieldwork in Lebanon, which was in the midst of a civil war. This was back in the 70s. In the PDRY, there were very few expats, mostly Sudanese and Egyptian communists. At the time, the only international NGO allowed to operate in the PDRY on a residential basis was the Swedish Save the Children.

LU: Standard question to anyone who lived in Yemen. Did you chew qat?

HL: Under the PDRY regime, chewing qat was only allowed on weekends and holidays. I had decided that if I was going to properly live in Yemen, I just had to learn how to chew. As you probably know, the stuff tastes absolutely foul, so I spent months training myself to tolerate it. I practiced and occasionally chewed with some Yemeni families. Then I moved to the YAR in 1982 and discovered everyone was chewing qat practically every single day! I decided then that my only solution to that problem and its side effects, such as lack of sleep, was to chew only on Thursdays. I am neither militantly anti-qat nor am I pro. I recognize it as a major element of the Yemeni economy, particularly for smallholders and those working in its value chain.

LU: You are often interviewed about Yemen’s political and social issues, but today we will discuss something more personal: your extensive collection of Yemeni artifacts. How did this collection come about?

HL: When I was living in Seyoun, the entertainment facilities were a little limited, and I am not a night person anyway, so on Fridays, when there was nothing much else to do, I would go to the handicraft souq. There was a woman named Sultana who was selling beautiful Hadrami dresses. So I kept buying them. I got about 20-30 of them. These highly decorated dresses, especially the Hadrami ones, were worn by Yemeni women even whilst working in the field. Others, such as the loose-fitting Tihami black or white ones, are impossible to find. Four from my collection have been accepted by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. I also have many cloths from Bait al-Faqih, a town in Tihama renowned for its weaving. Of course, over the years, the style and colours used have changed a lot. But I always used to buy what was in fashion that year. The mawaz, for example, (a traditional garment worn by men) went through many different trends. One year, they had tanks and guns woven into the pattern.

LU: You also have a rare collection of unbaked mud pottery from Hadramawt.

I first bought these pieces of pottery when I traveled to Hadramawt in 1977. The style has changed a lot since then, so you can’t find these anymore. Much of it comes from Tarim in Hadramawt, and was produced by a specific family there. They had created unique styles and paint patterns that evolved over the years. Unfortunately, after the senior woman of the family died, they stopped making them, and they are now a unique heritage collection. They also made beautiful unbaked incense holders and little toy sets, like tea and coffee sets, for children. A colleague in France wrote her master’s thesis on the pottery from this family in Tarim.

LU: I have noticed that whenever I see you speak about Yemen, you are always wearing this incredible Yemeni jewelry.

HL: I would say ninety-five percent of my jewelry is Yemeni, all of it made of silver. I make it a point of principle to wear Yemeni jewelry whenever I am talking about Yemen. And I never take off my Yemeni bracelets. Over time, I accumulated a large quantity; friends used to ask me to buy Yemeni jewelry for them whenever I was visiting Yemen, and I somehow ended up with sacks full of it. In Seyoun, I had my preferred jeweler, from whom I bought most of my pieces. The Seyoun silver souq was as good as the one in Sana’a, if not better. As far as I know, these are the only two cities in Yemen with good and sizeable silver souqs. Over the decades, I noticed that many jewelers in Sana’a switched to gold. When I first visited, most of the souqs sold silver, and there were only a few gold shops. Later, it was mostly tourists who were buying silver in the souq. Yemenis buy gold. But the quality is changing. I went to my “silver man” in Sana’a in 2013, and he was absolutely furious. “The Chinese are coming, buying our stuff, going home to make copies of it,” he said, “then coming back to sell it as Yemeni silver.”

LU: Many of the objects you collected reflect Yemen’s rich regional diversity. How do they speak to a broader sense of Yemeni identity and unity?

HL: You can’t drive in Yemen for more than two hours without a massive change of scenery. Yemen is so diverse – from the mountains to the terraces, to the desert, to the sea. A person from Al-Mahra is very different from someone from Sa’ada, from diet to culture to clothing to cultural expressions. Even though I accept the argument that, for example, Hadramis are very different from the rest of Yemen, there are also differences within Hadramawt itself, between the wadi and the coast. But those who know the country well can tell a Yemeni from someone from other parts of the peninsula.

Ultimately, there is something all Yemenis share, and even in these diverse artifacts, there is something distinctly Yemeni that you won’t find, let’s say, in Oman or Saudi Arabia. The difficulty is defining exactly what makes it Yemeni.

LU: Are there any pieces in the collection that hold special significance for you?

HL: It would have to be the model of the Seyoun Palace displayed at the exhibition in London. There was a brief period during which I had the keys to the Seyoun Palace. I was working there classifying documents that were found in its basement, just rolled up pieces of paper, mostly land tenure documents from the 19th and 20th centuries. I worked at the time with Jaafaar al-Saqqaf, a well-known cultural figure in Wadi Hadramawt. We cleared one room in one of the towers and put mats on the floor. We would go every morning with our flasks of tea and sit on our mats (I have a black-and-white picture somewhere). I couldn’t read the writing, so he would read to me. When we needed a break, I would wander around the palace. I learned my way around, as it is quite complicated with many apartments and divisions. No one was using it at the time, and it was between the PDRY regime’s plan to turn it into a hotel and the much better idea to turn it into a museum, but the work had not started yet. I even figured out which part of the palace I would have wanted to live in — my own private quarters. I would have to show you on the model.

LU: Yemen has experienced an assault on its cultural heritage during the past decade of war, a crisis that has not received significant attention in the media. Are you concerned about the future of Yemen’s cultural heritage?

HL: I spend more time worrying about the future of these artifacts, to be honest, as this is something that I personally need to deal with. But this is certainly a major concern that Yemenis should address with greater urgency. What has changed about Yemeni culture isn’t so much due to the war. If anything, these changes would be accelerating if it were not for the war. Of course, people are not thinking about these shifts because they are focused on more urgent matters, such as survival and coping with all the economic and humanitarian challenges. External influences, particularly the spread of globalized, mass market media and the use of artificial intelligence, pose a greater risk to the integrity of Yemeni culture than any conflict could. An example that comes to mind is how Yemeni music, for instance, is increasingly being Gulf-ized. The authenticity of local culture risks being eroded by this wave of artificial multimedia, which, while attractive to younger generations in particular, threatens to displace traditional forms of expression. This isn’t unique to Yemen — it’s a global trend. Many are not interested in preserving traditional culture. Understandably, they want to be modern and be part of the global system. This shift touches everything, from customs to clothing and artifacts.

LU: So, what message do you have for the younger generation of Yemenis who are trying to sustain and engage with these traditional practices and crafts?

HL: In 1980, I was walking around the Al-Qa’a souq in Sana’a. A couple of kids somehow found out that I was living in Aden. They all got very excited. “Aden must be wonderful,” they said. And I was thinking to myself, why would they be so excited about socialist Aden? And then they said, “All those modern buildings!” It turns out Aden’s block of flats, many of which were built by the Brits in the early 60s, had an allure. “We should destroy all of this lot here,” they added, gesturing widely at the old souq. The attractions of the “modern world” were as pronounced then as they are now. Today, many contemporary artists blend the old with the new. It’s creative, but it’s different from preserving heritage. This is about creating something new. And whyever not! Why should painters, for example, limit themselves to reproducing 18th-century styles when they can offer modern interpretations? The problem lies when you stop being proud of your own traditions. And from my experience, Yemen was a place where people had pride in their own culture and traditions. Yes, Taizis and Adenis were the first to start wearing suits, but many Yemeni men still proudly walked around in their mawaz. It is true of any culture: preserving and keeping heritage alive doesn’t mean walking around in loincloths. It is about valuing tradition, not being overly zealous about innovating or modernizing practices at the expense of traditions honed over centuries. I might be wrong, but I suspect there are significant numbers of younger generations who have perhaps lost that pride, and I am not sure it is because of the war. Some people want to emulate Elon Musk and have a Tesla. Others don’t.

LU: What is next for your collection?

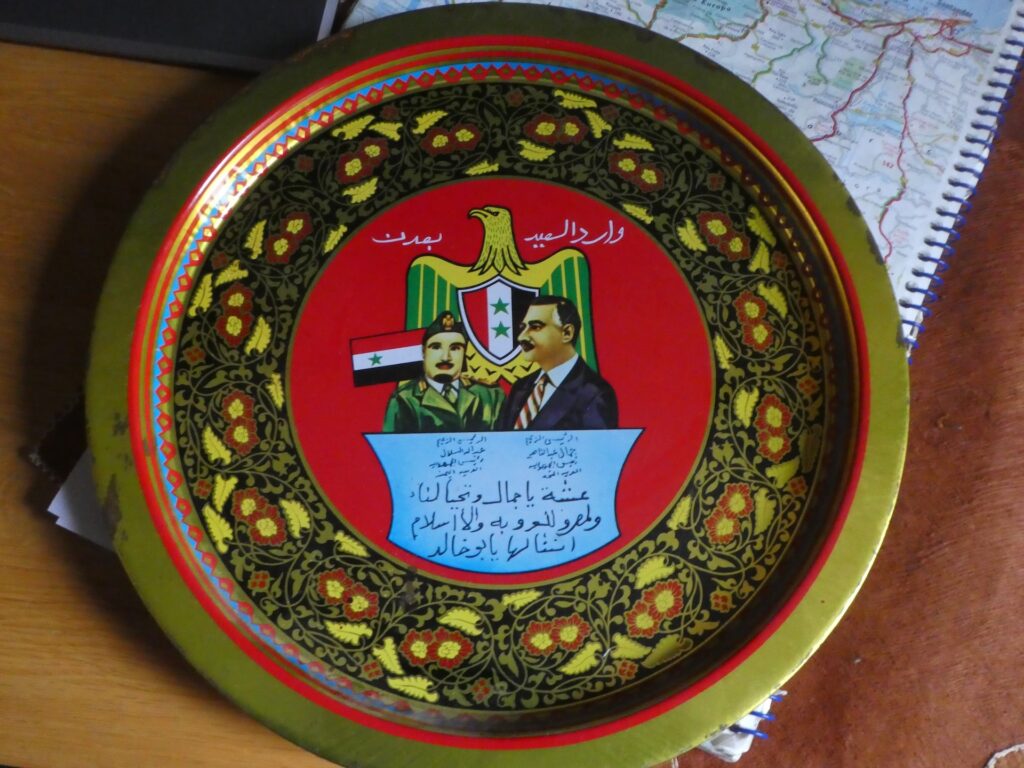

HL: For me, what matters most is finding a solution for the future of these artifacts. Arwa Othman had a small museum in Sana’a, filled with a far bigger and better collection of the kind of artifacts I have, including folk memorabilia. The Houthis came in and destroyed the whole lot. Returning my collection to Yemen in the current situation is not feasible. My focus is to catalogue and prepare these pieces so that, when the time is right, they can be returned to Yemen. It is important to hold on to these treasures. If you ever visit me in my house, where I have it all displayed, you will see I don’t go for high art, but for folk art. There is not enough of it to open an entire museum, but there is a lot there, including political memorabilia such as socialist-era badges, historical items like memorial trays, and even bits and pieces from the national dialogue. All this is part of history, and it should be in Yemen and available to Yemenis. It’s sitting in my house, which is all very nice, but I am not having the public enjoy these artifacts there. By doing this interview, I also look forward to good suggestions. I will keep the collection and find ways to store it until it goes to Yemen. Eventually, it should all go back to Yemen.

This article is part of a series of publications produced by the Sana’a Center and funded by the government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The series explores issues within economic, political, and environmental themes, aiming to inform discussion and policymaking related to Yemen that foster sustainable peace. Any views expressed within should not be construed as representing the Sana’a Center or the Dutch government.