The past year has been one of extreme consequence for Yemen. The war has entered a new phase of low-level violence and economic warfare. Casualties are down since a truce was signed in April, and have remained relatively low even after its acrimonious expiration in October. The internationally recognized government has sworn in a new executive body, but it has been unable to bridge internal rifts or reverse the territorial and economic decline of recent years. The United Arab Emirates has fully re-engaged in Yemen through a variety of proxy groups, most importantly the secessionist Southern Transitional Council (STC), which holds sway across much of southern Yemen. Saudi Arabia is pursuing talks of its own with the Houthis, though its willingness to sideline the government and wash its hands of the conflict could have unforeseen, potentially disastrous effects. The Houthi movement remains entrenched in the populous northwest, and though it faces economic and governance challenges of its own, it continues to build and administer a conservative, theocratic state, curtailing the rights of women and appropriating civilian land. It is unclear whether the Houthis can be brought to terms and the country spared further division. But the relative success of the truce and the continuing talks are hopefully a sign that negotiation and mediation can replace the bitter violence that has marked the last decade.

Figure 1. Yemen Zones of Control

Timeline of Major Events

- The UAE-backed Giants Brigades push Houthi forces out of northwest Shabwa and parts of southern Marib, foiling Houthi efforts to capture Marib city and nearby oil and gas infrastructure.

- Houthi forces launch drones and missiles at an oil facility and the airport in Abu Dhabi, killing three civilians, the first such attack in the UAE since 2018. Two further attacks cause no damage.

- The outbreak of war in Ukraine leads to increased economic hardship across Yemen due to spikes in the global prices of oil, wheat, and other commodities. Yemen had imported substantial amounts of wheat from both countries.

- The Houthis step up attacks on Saudi oil facilities, causing a temporary drop in output at a refinery.

- Houthi authorities make a preliminary agreement with the UN to offload 1.1 million barrels of oil aboard the decrepit FSO Safer tanker moored off Hudaydah.

- Saudi Arabia organizes a week-long conference in Riyadh for consultations with Yemeni political leaders.

- A two-month truce is announced by the UN Special Envoy for Yemen.

- Under Saudi and Emirati direction, a Presidential Leadership Council is formed in Riyadh, replacing President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi.

- Saudi Arabia and the UAE pledge US$1 billion each in financial support for the internationally recognized government, with another US$1 billion from Riyadh for development projects and fuel imports.

- Commercial flights resume between Amman and Sana’a as part of the UN-backed truce.

- The truce is extended for two months despite disagreement over reopening roads around the Houthi-blockaded city of Taiz.

- Riyadh commits US$400 million for development projects and US$200 million in oil derivative grants, helping stem a collapse in the value of the rial in government-held territory.

- A popular Islah-affiliated commander of the Special Security forces in Shabwa survives an assassination attempt by members of the UAE-backed Shabwa Defense forces, marking the start of a battle for control over the governorate.

- The UAE-backed Giants Brigades and STC-backed Shabwa Defense forces violently expel Islah-affiliated forces from Shabwa, creating a crisis within the PLC.

- The truce is extended for another two months, though Houthi forces try to take control of the last major government-controlled road out of Taiz city.

- The STC deploys in Abyan in a nominally counterterrorist campaign against Al-Qaeda elements in the governorate. It also forces out Islah-aligned units, disobeying orders from PLC head Rashad al-Alimi.

- Flooding continues to devastate areas across the country, affecting at least 51,000 households since April.

- The STC mobilizes street protests in Hadramawt and Al-Mahra, demanding the removal of Islah-affiliated troops in the 1st Military Region based in Seyoun.

- STC and government forces continue operations in Abyan aimed at driving out Al-Qaeda forces from strongholds in the governorate.

- The truce lapses after the parties fail to agree terms for paying public sector salaries or reopening roads, but there is no return to major fighting.

- Saudi-backed tribes in Hadramawt begin organizing against UAE-backed STC mobilization.

- PLC head Al-Alimi attends the UN climate conference in Egypt, as part of a weeks-long tour abroad that includes visits to the US for the UN General Assembly, the UAE, Jordan, and Algeria.

- The Houthis begin a series of drone and missile attacks on southern ports to scare away oil shippers, creating a new economic crisis for the government.

- Reports emerge of backchannel Saudi-Houthi talks, which are initially presented as discussions on a prisoner exchange.

- The government designates the Houthi movement a terrorist organization following attacks on oil export terminals in Shabwa and Hadramawt, which continue in November.

- The International Monetary Fund agrees to provide US$300 million to the central bank in Aden, with the US facilitating transfers through the Federal Reserve.

- Saudi Arabia and the UAE finally agree to release the financial support pledged in April. The Arab Monetary Fund signs a US$1 billion agreement with the Yemeni government to support economic reforms.

December

- PLC head Al-Alimi spends some two weeks in Aden for the first time in months. Other PLC members continue to avoid the interim capital due to internal tensions, STC security control, and concern over Houthi drone attacks.

- Tareq Saleh, a PLC member and head of the National Resistance forces, strengthens his position as scion of the Saleh family by leading celebrations marking the death of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh.

- The opening of Al-Mokha airport raises the profile of Saleh’s UAE-backed National Resistance forces, which guard a critical section of the Red Sea Coast.

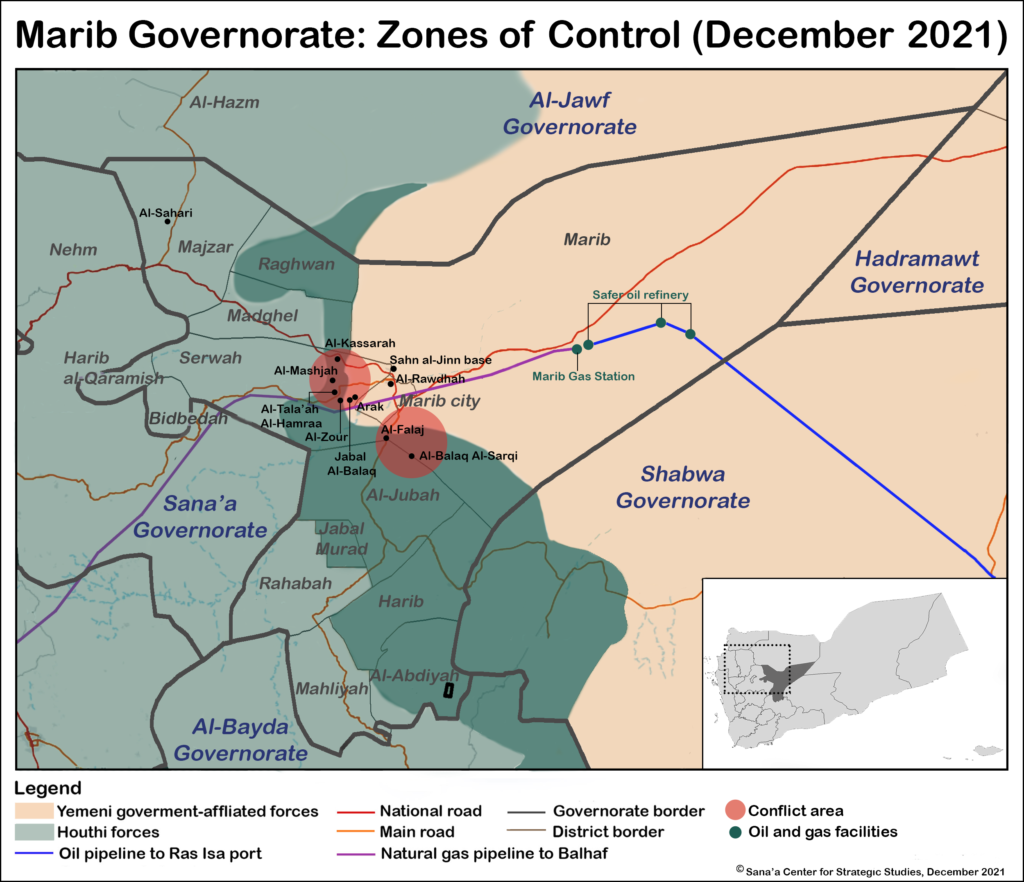

The Battle for Marib

The conflict between the armed Houthi movement and the internationally recognized government hung in the balance at the start of 2022, as Houthi forces continued to press their years-long offensive against Marib city. Houthi attacks had continued unchecked for months, and the war appeared to be entering its final stages, with the group seemingly on the verge of breaking through to the last government stronghold in northern Yemen.[1] Marib’s oil fields and gas infrastructure would secure the movement with long-term revenue to underwrite its de facto state, but the timely intercession of UAE-backed forces over the winter dashed these plans. After pulling back from frontlines on the Red Sea Coast in November 2021, the Giants Brigades counterattacked in Shabwa in early January. The Emirati-backed brigades quickly asserted themselves as the Saudi-led coalition’s most effective fighting force, and supported by airstrikes, drove the Houthis from the southern governorate and expanded the battle to parts of southern Marib and Al-Bayda in a matter of weeks. By late January, the frontlines around Marib had largely stabilized.[2]

Figure 2. The High-Water Mark of the Houthi Offensive

The Houthi’s failed gambit to seize Marib marked a turning point in the conflict. Until that moment, it was unclear how far their territorial ambitions extended, and whether they might ultimately pursue the conquest of the entire country, as their rhetoric suggested. The coalition, riven by infighting and competition, was unwilling or unable to compete on the battlefield. But the repeated assaults on Marib and the confrontation with the Giants Brigades induced an enormous number of Houthi casualties and put to bed any notion of rapid territorial expansion. The failure to take Marib’s oil and gas infrastructure removed an important potential source of revenue, which has forced the movement to look elsewhere for resources to prop up its flailing economy and fund its war machine. The conflict has now taken on a markedly different flavor, distinguished by economic warfare, faltering truces, poisonous negotiations, and continued low-level, targeted violence.

The successful deployment of the Giants Brigades heralded an intensification of Emirati engagement in Yemen. It ended the period of relative peace between the UAE and the Houthis that had persisted since the 2018 Stockholm Agreement, which halted the advance of coalition-backed troops up the Red Sea Coast toward Hudaydah. Oman, the Houthis’ primary interlocutor, had negotiated an unwritten ceasefire with the Emiratis, but this fell apart abruptly with the fighting around Marib. The Houthis were quick to retaliate, launching drone and missile strikes on an oil facility and the Abu Dhabi airport, the first such attacks since 2018. In March, they struck an oil depot in the Saudi city of Jeddah, only days before the city held a Formula One race.[3] The coalition responded with intensive air strikes, which reached their highest levels in months.

The deployment of the Giants Brigades and their rapid success also marked the beginning of the end for the primacy of Yemen’s Islah party. The group enjoyed substantial influence through Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar and had large numbers of affiliated troops deployed to fronts in Marib and Shabwa. The Emirates maintained a longstanding animus toward Islah due to the Islamist party’s ties with the Muslim Brotherhood. Abu Dhabi’s massive increase in support and engagement with its Yemeni proxies, particularly the STC, altered the balance of power among the coalition’s domestic partners and sowed the seeds of further internecine violence.[4]

The Presidential Leadership Council

2021 began in the shadow of an inauspicious Houthi attack on Aden airport as the newly-formed cabinet of the internationally recognized government came under fire before they could even deplane.[5] The return of the government to the interim capital did not instill institutional unity or provide the reforms necessary to reverse battlefield misfortunes or economic decline. With the cabinet ineffective, in 2022 Yemen’s suzerain backers again contemplated formulations that might best represent their interests through the dominant military forces on the ground. The Saudis appeared ready to move on from the conflict. Incumbent President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi had long been perceived as an ineffective leader, and his health appeared increasingly frail. His installation as president was never intended to last a decade. Hadi had been unable to bridge divisions in his government, which had lost huge swathes of territory to the Houthis, and spent most of his term in enforced exile.[6] The longer he remained in power, the less legitimacy the government was able to claim.

Yemen’s leaders were summoned to Riyadh in late March for consultations. After a series of hasty backroom talks, an eight-member Presidential Leadership Council was announced under the auspices of the Gulf Cooperation Council in the early hours of April 7. Headed by former interior minister Rashad al-Alimi, the council gave new roles and authority to a number of prominent military chiefs, including Aiderous al-Zubaidi, the leader of the STC, and Tareq Saleh, head of the National Resistance Forces. Ostensibly designed as a representative Yemeni body, its creation was intended to bring together Saudi and Emirati proxies so that the Gulf states could better coordinate the war and negotiations as they charted Yemen’s future.[7]

Figure 3. The Presidential Leadership Council

Presidential councils have historical precedent in Yemen, but there was no provision for such a body in the constitution. Its legitimacy and authority were widely accepted on a de facto, rather than de jure basis, both by the international community and the UN Special Envoy, reflecting both dissatisfaction with the previous administration and a tacit acknowledgment of Saudi interests. Rather than a multi-party executive representing Yemeni interests, the council, envisioned and installed by Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, was a fragile coalition of foreign-backed warlords. For his part, Hadi readily complied, firing Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar and turning over power.[8]

The optimism that accompanied the transition was less prescient than suspicions of further Saudi and Emirati interference and control.[9] Competition between the council’s members undermined the government from its inception and has at times devolved into violence, notably in Shabwa. PLC chief Al-Alimi owed his authority entirely to the Saudis, and unlike other council members, had no military forces of his own. His primacy was repeatedly challenged, most often by Al-Zubaidi, who made a point of receiving visitors and even hosting a cabinet meeting when Al-Alimi was out of the country. STC security control over the interim capital Aden posed a further obstacle to the council’s success. At times, Al-Alimi appeared to align himself with Al-Zubaidi, perhaps seeking a powerful ally. But when he took independent action, albeit with the support of his Saudi sponsors, Al-Alimi was often met with a chorus of objections from other council members.

The creation of the council was an admission that the Saudis had made a mistake in backing Hadi’s foundering regime for so long, but the results were similar – a fractured and divided anti-Houthi camp. Council members were beholden to their suzerain backers for their positions and military strength, and had different priorities and political visions. They were often called away to Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to receive instructions, or kept there to keep them from meddling. Early attempts by the Emiratis to extend influence through the council faced pushback, so they encouraged their proxies to make moves on the ground instead, leading to further destabilization. As an executive body, the PLC failed to centralize authority or delegate responsibilities between its members. In sum, the council appeared incapable of organized, collective action, and unable to contest the division of the country or negotiate its reunification.

The Truce

On April 2, UN Special Envoy for Yemen Hans Grundberg announced a truce had been agreed between the government and Houthi movement. The deal ushered in the longest period of sustained abstinence from major conflict during the war, and casualties dropped precipitously.[10] The truce quickly provided for the long-awaited resumption of commercial flights out of Sana’a airport and the reopening of the port of Hudaydah.[11] The deal also included framework agreements for the opening of roads in and around the besieged frontline city of Taiz, and for the payment of long-overdue public sector salaries in both government and Houthi-controlled areas. Employees in the bloated public sector had gone unpaid for long stretches during the conflict, and across Yemen civilians were in dire need of financial assistance.

The truce was renewed for two months in June, and again in August. Discussions over road reopenings and access to the Houthi- blockaded city of Taiz made little progress, with proposals and counterproposals passed back and forth without agreement.[12] During the negotiations, the Houthis continued military operations to take control of the last remaining road connecting the city with the interim capital Aden. The provision of public sector salaries, to be paid by Saudi Arabia and government oil revenues, appeared at one point to be imminent, as a step toward a broader deal. But a last-minute Houthi demand for the payments to include military and security personnel hired during the war scuttled the talks, allowing the truce to lapse on October 2.[13]

Much was made of the truce, and there was widespread hope that it would presage further dialogue toward a final settlement or alleviate the war’s humanitarian and economic consequences.[14] Such hopes were given credence by the truce’s extension and the decline in casualties. But when Houthi brinksmanship led to the breakdown of talks,[15] recriminations were quick to follow.[16] The Houthis were widely seen as having negotiated in bad faith and making maximalist demands. If they return to a UN-backed peace process, which seems unlikely, they will meet a far more skeptical audience.

Despite the formal end of the truce, there was no rapid resumption of hostilities.[17] There were no major ground offensives conducted by either side after the agreement expired, and an informal ceasefire took its place. Low- level violence on the frontlines, which persisted during the truce, carried on. The lack of major fighting may hint at why a deal was struck in the first place. The PLC was installed by Saudi Arabia in part to work to end the war. The council was fragmented and its existence nearly derailed by infighting. It was unable to address persistent economic deterioration in government controlled-areas, which led to local protests. At no point did it appear capable of unified military action. The Houthis suffered massive casualties in their attempt to seize Marib and its oil fields, and were incapable of mounting another large-scale offensive in the short term. And the status quo served their interests – the longer they hold on to populous northwest Yemen, and the longer their state-building project continues, the more entrenched their rule becomes.

The pause in hostilities did, however, sow fissures in the Houthi camp, as commanders returning from the frontlines came into conflict with officials in Sana’a, each laying claim to their share of the spoils of war. Poor economic conditions in the north, exacerbated by unpaid salaries and the suspension of imports, increased competition for resources, provoked political bickering and greater exploitation of the vulnerable populace. Houthi forces increasingly came into conflict with locals over the requisition of farmland and other property.

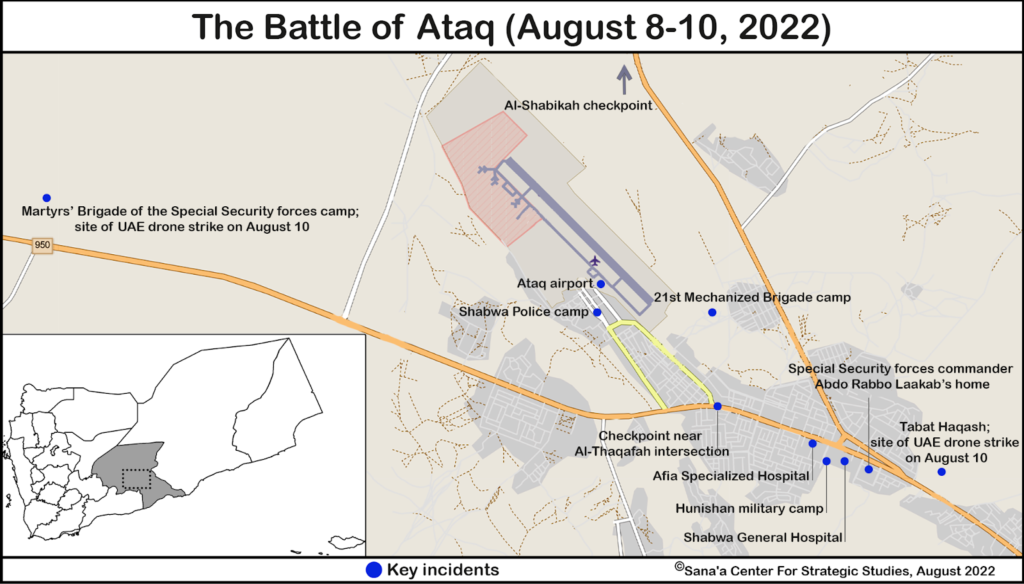

The Fight for Shabwa

Divisions among the anti-Houthi alliance exploded into violence in early August, when the confrontation between the Islah party and the STC finally boiled over into pitched battles in Shabwa. Hostilities began when the Islah-affiliated commander of the Special Security forces in Shabwa, Brigadier General Abd Rabbo Laakab, survived an assassination attempt by members of the UAE-backed Shabwa Defense forces in July.[18] On August 8, wholesale fighting broke out between Islah and STC-affiliated forces in and around the governorate capital Ataq. Shabwa is strategically important for its oil and gas reserves, including the Balhaf LNG facility, occupied by Emirati troops. The fighting ended decisively after the intervention of the UAE-backed Giants Brigades, and Islah-affiliated forces were driven north to Shabwa’s border with Marib.

Figure 4. The Battle of Ataq

The fighting marked the continued marginalization of the once powerful Islah party and its affiliates, and the growing influence of the UAE and its proxies in southern Yemen.[19] It produced a political crisis within the PLC, which failed to head off the brewing dispute and struggled to manage its fallout.[20] But even as a broader crisis appeared to have been averted, the STC pressed its advantage. The group launched a series of nominally counter-terrorist operations in Abyan and Shabwa, seeking to extend their influence.[21] These succeeded in displacing a number of camps run by Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in Abyan, but also targeted Islah troops for removal, over the strong objections of PLC head Al-Alimi. It is unclear if the sweeps will accomplish lasting change: AQAP has retaliated with increased IED attacks against counterterrorism forces.

The STC also expanded its influence through non-violent means. It repeatedly agitated against the presence of 1st Military Region forces in Hadramawt, which are dominated by Islah-affiliated troops. As the year drew to a close, the STC orchestrated increasingly organized and regular protests, which drew counter demonstrations by local groups wary of the party’s encroachment. These have drawn support from Saudi Arabia, revealing the competing interests and influence of the two main coalition partners.

The Economic War

The cessation of major ground hostilities pushed the conflict into other realms, notably control over Yemen’s economy.[22] When their eleventh-hour demand for the payment of military and security salaries was rejected, the Houthis were deprived of a much-needed source of revenue. In retaliation, they deprived the government of the same, targeting oil tankers at ports on the southern coast in late October and November.[23],[24] The strikes effectively halted the export of oil and gas, as ships could no longer safely dock, and suspended the government’s primary source of revenue indefinitely.[25],[26] Senior government officials estimated the strikes had cost the government some US$500 million by the start of January 2023, and the loss has been even more consequential than this figure suggests: the country’s economy has been deteriorating for years, and the value of the new rials that circulate in the south is fragile. Fluctuating prices and shortages of petrol, gas, and electricity sparked protests in southern Yemen in June.[27]

The government immediately recognized the existential threat posed by the strikes, but had limited options for response. Alone, it was incapable of countering such operations, and lacked the military means to retaliate with compellence. They may have been warned off such action by their Saudi and Emirati backers, who were keen to avoid a military escalation as global attention turned to the World Cup in Qatar in November.

Faced with such constraints, the government designated the Houthis a terrorist organization.[28] The move initially appeared as if it might backfire – the Saudis had little appetite for it, and the US repealed its own designation in early 2021. Yemen’s economy remained relatively integrated in some sectors, and any damage visited on Houthi-held areas would ultimately affect the whole country. But the government was careful, moving ahead with targeted sanctions against individuals and businesses affiliated with the Houthi movement.[29]

Nevertheless, the bifurcation and deterioration of the economy continued.[30] The Central Banks of Yemen (CBY), split between Sana’a and Aden, increasingly pursued different policies. The CBY-Aden requested that banks hand over data as part of government efforts to enforce sanctions and to meet requirements by the International Monetary Fund for compliance with Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) statutes.[31] The Houthis threatened organizations that comply, and pushed ahead with their own directives to move banks into compliance with a strict and likely unfeasible version of Islamic finance.

Yemen’s road system remains a mess, with frontlines and landmines making large swathes of the country’s transportation network off limits. Deprived of other revenue streams, armed forces have set up numerous checkpoints to extract illegal tolls from private cars and commercial transport. More than one hundred bridges and approximately one-third of the paved roads have been destroyed in military operations over the course of the war.[32] Negotiations to open roads to besieged cities – notably Taiz – have stalled.[33] The weaponization of the transport network – by both sides – has compounded the damage caused by the war, and exacerbated economic decline.

The government has received substantial financial support from abroad to prop up the currency and finance imports. At year’s end, a combined US$2 billion in promised Saudi and Emirati funding appeared as if it would finally be disbursed, after being held up by the government’s purported slowness in instituting requisite reforms. In November, the Arab Monetary Fund signed a $1 billion dollar deal to support economic reforms, and the International Monetary Fund agreed to release $300 million in Special Drawing Rights, facilitated by the US Federal Reserve.[34] But the government will need massive and sustained assistance to survive the combined misery wrought by the wartime economy and the suspension of hydrocarbon exports.

Restrictions on Women’s Rights

The past year saw a marked increase in repressive measures against women, particularly in Houthi-controlled areas. The Houthis enforced a policy whereby the approval or accompaniment of a male guardian, or mahram, was required for women to conduct all manner of activities, including travel. Yemenia Airways began to request not just the officially authorized approval of a guardian, but for a male member of the family to accompany a woman on a flight.

Although restrictive gender norms are common in Yemen, such measures are unprecedented and risk entirely removing women from public life. The restrictions reflect the severe and conservative theocratic state being constructed by the Houthis in the territories they control. The longer they hold power, the more institutionalized such oppressive measures become. Houthi efforts to enforce the celebration of religious holidays, police women with female militias, change school curriculums, hold indoctrination camps for youths, and their continued use of child soldiers all reflect a readiness to impose a specific ideological program.

While the Houthi project is the most extreme, the government has done little to include women, either in governance or in peace negotiations. Despite women playing critical roles in peacebuilding and reconciliation at the local and national levels,[35] they have been largely excluded from efforts by the government to bridge internal divisions or negotiate with the Houthis. Yemen’s own National Dialogue Conference (2013-2014) found acceptance of a 30 percent minimum threshold for women’s participation in government institutions, but this has been roundly ignored. The newly installed PLC notably did not include any women, and the government has not even paid lip service to prioritizing their inclusion.

The consequences of such deepening repression are dire. Not only are they a fundamental attack on the rights of Yemeni women – they remove the agency of half of Yemeni society at the time when it is most needed. The country is in want of peacemakers, and yet it marginalizes women with ample experience in these roles. The economy has cratered, and yet the women who have moved into the workforce to support their families may now be pushed back out again.[36] To date, the government and the international community have failed to adequately prioritize women’s rights and participation.

Saudi-Houthi Talks

The Houthis and Saudis have had ongoing contact since the outset of the conflict,[37] but talks took on new prominence and publicity after the expiration of the truce.[38] By the end of the year, a deal between the two parties was reported to be imminent in some quarters, with provisions for the payment of public sector salaries and discussions of a final settlement. The talks, facilitated by Oman, represented the changing calculus of the sides. Saudi leader Mohammed bin Salman is still young, and keen to extricate his country from a conflict that has been a military and public relations disaster. The Saudis perhaps now view the Houthi presence on their southern border as an unpleasant political reality rather than a problem that can be removed militarily. Negotiating independently could speed their exit, unencumbered by the divergent motives of the UAE, the squabbling government, and a stalled UN peace process.

Some Houthis believe that they have succeeded in defeating a coalition of seventeen countries through divine intervention, and are now out to dictate the terms of the peace.[39] Their costly failure to take Marib may also have limited their aspirations to the massive territory they already hold. Equally, they may have considered the demographic burden of population centers like Taiz and Marib, and that residents might forever be too difficult to control. Negotiating directly with a sovereign state has provided the movement with a degree of legitimacy as the government in place in northwest Yemen – the Houthis are acutely aware of this fact, and request that the Saudi delegation responds to their demands in writing.

The bilateral negotiations leave the Yemeni government in a very dangerous position. The country is now suffering the rule of yet another Saudi- imposed executive, and in its diminished state it is entirely depending on Saudi Arabia and the UAE for financial and military support. In previous talks, the Saudis insisted that the government be at the table. This time, they have been further marginalized and will have little choice but to acquiesce to whatever terms are agreed.

If the Saudis do cut a deal, it will likely entail an agreement for the payment of public sector salaries and reconstruction aid, in effect a bribe for the Houthis to stop targeting Saudi territory and oil facilities. But this leaves in place the government’s other backer: the UAE has adamantly refused to negotiate with the Houthis and has reportedly rejected overtures from intermediaries. Their increased involvement in Yemen over the past year does little to suggest they will be quick to abandon their proxies or relinquish their hard-won influence. Apart from their financial commitments to the Yemeni state, they have recently begun to pursue a large arms deal to better equip government forces. But the Emirati’s primary proxy remains the Southern Transitional Council. A Saudi deal recognizing Houthi control might push the STC to advance its secessionist project. The Emirati position on such designs remains ambiguous.

This outcome could be a disaster, posing new, perhaps insurmountable challenges for Houthi authorities and the STC. Large parts of the population now living under Houthi rule do not share its religious zeal or approve of its repressive measures. Dissent has spilled into the open as conditions worsen, and the group has come down hard on activists, lawyers, and even comedians who speak out. The STC is equally unpopular among some constituencies in the south – as the mobilization campaigns now being waged in Hadramawt attest. It is wholly unclear whether the Houthi north is economically viable on its own or whether it would, in time, deteriorate into further violence and humanitarian disaster. Should the STC attempt to declare an independent state in the former South Yemen , the internal divisions it already faces would take center stage. But with the Saudis exercising their leverage on their own behalf, rather than the government’s, the prospect of a divided Yemen comes quickly into focus.

Other Developments in Brief

The War in Ukraine

Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Yemen imported 46 percent of its wheat from the two countries,[40] which produce the low-cost varieties used for humanitarian aid and imported into food insecure environments. The outbreak of war provoked a global spike in food prices, and the blockading of Ukrainian ports by Russian naval forces jeopardized the delivery of food to Yemen and other countries in need. Concern by Yemen’s warring parties over the knock-on effects of the war in Ukraine may have contributed to the signing of the April truce. With the help of the World Food Programme, the government was able to arrange grain shipments from other sources, and an agreement brokered by Ankara provided for the renewed export of some Ukrainian grain by August.[41]

FSO Safer

The FSO Safer, a derelict offshore oil storage vessel floating in the Red Sea, continues to menace the region despite a framework UN deal to safely decommission the ship and offload its cargo. In September, the UN announced that it had made an agreement with the Houthis to remove the oil to another vessel, and later that it had secured the funds for the first phase of this operation to go ahead.[42] Backtracking by Houthi authorities and a shortage of funds have repeatedly stalled the project, and the operation has yet to commence.[43] The failure to remove the oil is extremely risky; if the vessel breaks up it would be a catastrophe for the Red Sea ecosystem and devastate related industries, including Yemen’s fisheries.

Flooding

Yemen was stricken by flooding throughout the summer, destroying crops and houses and causing more than a hundred fatalities.[44] More than 50,000 households were affected, as rains collapsed roofs and destroyed homes from Sana’a to Hudayah.[45] The ramifications were felt particularly in IDP camps, where rudimentary and temporary shelters were washed away. Nor did the misery subside with the floodwaters: rain and flooding displaced numerous landmines from known minefields and frontline areas, redepositing them in roads, fields, and villages.

The 2022 Yemen Annual Review was prepared by:

Lead writer – Ned Whalley

Analysis – Yasmeen al-Eryani, Abdulghani al-Iryani, Farea al-Muslimi, Maged al-Madhagi, Osamah al-Rawhani, Maysaa Shuja al-Deen, Wadhah Al-Awlaqi

Editorial – Ryan Bailey, Andrew Hammond, Lara Uhlenhaut

Graphics and Maps – Ghaidaa al-Rashidy

Translation – Elham Omar

PDF design- Khadiga Hashim

This analysis is part of a series of publications produced by the Sana’a Center and funded by the government of the Kingdom of The Netherlands. The series explores issues within economic, political, and environmental themes, aiming to inform discussion and policymaking related to Yemen that foster sustainable peace. Views expressed within should not be construed as representing the Dutch government.

- “After al-Bayda, the Beginning of the Endgame for Northern Yemen?,” International Crisis Group, October 14, 2021, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/yemen/b84-after-al-bayda-beginning-endgame-northern-yemen

- “State of the War, The Yemen Review, January-February 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 15, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/jan-feb-2022/17005

- Hassan Ammar, Jerome Pugmire, and Jon Gambrell, “Yemen rebels strike oil depot in Saudi city hosting F1 race,” Associated Press, March 26, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/business-sports-united-arab-emirates-saudi-arabia-yemen-a0673736ceddfd5f498deb16a4254d64

- “Clashes in oil-rich Shabwa test Yemen’s new presidential council,” Reuters, August 11, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/clashes-oil-rich-shabwa-test-yemens-new-presidential-council-2022-08-11/

- Mohammed Mukhashaf, “Twenty-two killed in attack on Aden airport after new Yemen cabinet lands,” Reuters, December 30, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-idUSKBN29413E

- “Factional chaos, missteps brought down Yemen president Hadi,” Reuters, April 7, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/factional-chaos-missteps-brought-down-yemen-president-hadi-2022-04-07/

- Ghaida Ghantous, “Explainer: Saudi Arabia shakes up Yemen alliance in bid to exit quagmire,” Reuters, April 7, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/saudi-arabia-shakes-up-yemen-alliance-bid-exit-quagmire-2022-04-07/

- Mohamed Ghobari and Ahmed Tolba, “Yemen president cedes powers to council as Saudi Arabia pushes to end war,” Reuters, April 8, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/yemen-president-relieves-deputy-his-post-2022-04-07/

- “Hadi Out, Presidential Council Takes Over,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 8, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/17378

- “Ramadan Truce Largely Holding, The Yemen Review, April 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 3, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/april-2022/17711

- “First commercial flight takes off from Sanaa, raising hopes for Yemen peace,” Reuters, May 16, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/first-commercial-flight-takes-off-sanaa-raising-yemen-peace-prospects-2022-05-16/

- “Taiz Siege Continues as Talks Face Roadblocks, The Yemen Review, June 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 11, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/june-2022; Suleiman Al-Khalidi, “Yemen’s Houthis must act on Taiz to show commitment to truce, minister says,” Reuters, August 8, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/yemen-fm-says-iran-aligned-houthis-not-committed-key-parts-un-brokered-truce-2022-08-08/

- “Houthis Target Southern Ports, The Yemen Review, October 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 14, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/october-2022

- Omar Munassar, “Failed Truce Reflects Houthi Willingness to Leverage Gov’t Divisions, Global Needs,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 14, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/october-2022/18996

- “Houthis Scuttle Truce Talks with Last-Minute Demands, The Yemen Review, September 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 13, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/september-2022/18807

- Ahmed Al-Haj, “Yemen’s warring sides fail to extend UN-backed truce,” Associated Press, October 2, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-united-nations-yemen-civil-wars-sanaa-ba7d97673e3330ba85a34e6b11560c31; Jack Jeffery, “US envoy blames Houthis for failure to extend cease-fire,” Associated Press, October 5, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-yemen-sanaa-houthis-308e604fabc9ed568c4d9cfed1aa7e79

- “Frontlines Remain Relatively Calm Despite Houthi Drone Attacks Against Southern Ports, The Yemen Review, November 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 16, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/november-2022/19203

- “Tensions between Islah- and STC-Affiliated Forces in Shabwa Explode with Assassination Attempt, The Yemen Review, July 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 12, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/july-2022/18396

- Maged Al-Madhaji, “Defeat in Shabwa Forces Islah to Reckon With New Political Reality,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 18, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/18497

- “Showdown in Shabwa Shakes Government, The Yemen Review, August 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 8, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/august-2022

- “Yemeni southern separatists launch military campaign in Abyan,” Reuters, August 23, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/yemeni-southern-separatists-launch-military-campaign-abyan-2022-08-23/

- Mohammed Alghobari and Reyam Mokhashef, “Yemen rivals ramp up economic war as U.N.-backed truce efforts limp,” Reuters, December 8, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/yemen-rivals-ramp-up-economic-war-un-backed-truce-efforts-limp-2022-12-08/

- Ahmed Al-Haj, “Yemeni rebel drones target Greek ship in government-run port,” Associated Press, October 22, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/iran-houthis-middle-east-sanaa-yemen-04ce841d3268f200e393bf7d71e767e3

- Ahmed Al-Haj, “Yemen: Houthi drones attack ship at oil terminal,” Associated Press, November 21, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-business-yemen-sanaa-houthis-c115994692a5c2db28f14d74895e00c3

- “Oil Exports Remain Halted as Govt Agrees Terms for International Support, The Yemen Review, November 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 16, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/november-2022/19204

- “Oil Port Attacks Threaten Government Finances, The Yemen Review, October 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 14, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/october-2022/19013

- “PLC President Faces Aden Protests After Regional Tour, The Yemen Review, June 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 11, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/june-2022/18142

- “Houthi Strikes Prompt Government Terrorism Designation, The Yemen Review, October 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 14, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/october-2022/19003

- Ibid.

- “Deescalate the Economic War, The Yemen Review, October 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 14, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/october-2022/19002

- “Oil Exports Remain Halted as Govt Agrees Terms for International Support, The Yemen Review, November 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 16, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/november-2022/19204

- Casey Coombs and Salah Ali Salah, “The War on Yemen’s Roads,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 16, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/19304

- Samy Magdy, “Rights groups urge Yemen’s Houthis to end Taiz blockade,” Associated Press, August 29, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-yemen-blockades-sanaa-human-rights-watch-01be29656956d4823255ab8c48f08a19

- “Arab Monetary Fund signs $1 bln agreement to support Yemeni government reforms – Saudi state media,” Reuters, November 27, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/arab-monetary-fund-signs-1-bln-agreement-support-yemeni-government-reforms-saudi-2022-11-27/

- Maryam Alkubati, “Women’s Voices in Yemen’s Peace Process: Priorities, Recommendations, and Mechanisms for Effective Inclusion,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 25, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/19400

- Fawziah Al-Ammar, Hannah Patchett, and Shams Shamsan, “A Gendered Crisis: Understanding the Experiences of Yemen’s War,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 15, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/19400

- Hussam Radman, “Local Deadlock and Regional Understandings: Analyzing the Houthi-Saudi and Islah-UAE Talks,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 16, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/november-2022/19208

- Samy Magdy, “Yemen rebels, Saudis in back-channel talks to maintain truce,” Associated Press, January 17, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/politics-yemen-government-saudi-arabia-houthis-2b3a40079aaf6ce6bac9817d86d8c52a; “How Huthi-Saudi Negotiations Will Make or Break Yemen” International Crisis Group, December 29, 2022, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/yemen/b089-how-huthi-saudi-negotiations-will-make-or-break-yemen

- Abdulghani Al-Iryani, “The Saudi Overture to the Houthis,,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 14, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/october-2022/18992

- Samy Magdy, “UN: First grain shipment departs Ukraine for war-torn Yemen,” Associated Press, August 30, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-middle-east-united-nations-black-sea-81a6d5e52940412d1c0033958292b8a4

- “WFP Secures Ukrainian Grain Shipment for Yemen, The Yemen Review, August 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 8, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/august-2022/18645

- Ellen Knickmeyer, “UN: Pledge goal reached for averting oil disaster off Yemen,” Associated Press, September 19, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-united-nations-yemen-32f9e9b1832e1a2d5f1e652d2a3cef0b

- Edith M. Lederer, “UN: Cost is new obstacle to oil transfer from Yemen tanker,” Associated Press, January 18, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/oil-spills-united-nations-yemen-business-4ec17509e2284b3412a35438a0b38d00

- “Summer Flooding Affects Thousands, The Yemen Review, August 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 8, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/august-2022/18644

- Ibid.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية