Editorial

Delusions of Victory Laid to Rest

Through most of 2021, the armed Houthi movement appeared unstoppable. As their forces pushed relentlessly toward Marib city, the fall of the last government stronghold in the north began to seem inevitable. Rich in oil and gas, its loss would be a mortal blow to the spiraling economy and political legitimacy of the internationally recognized government. Along frontlines across the country, Houthi forces either held their ground or advanced, showing a cohesiveness, discipline and effectiveness unmatched by the motley array of armed groups opposing them. Houthi drones and ballistic missiles flew across the border into Saudi Arabia, and continued even in the face of retaliatory airstrikes, heightening the cost of conflict for the coalition.

Houthi military efforts were buttressed by developments behind the frontlines and beyond Yemen’s borders. A significant threat to the movement emerged and vanished without the Houthis even having to respond. The group was designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) in January 2021 as a swan song of the Trump administration in Washington, but the decision was rescinded less than a month later by newly inaugurated US President Joe Biden after the United Nations and aid organizations testified it would paralyze humanitarian operations. For Houthi leaders, it was an affirmation of their strategy of holding the wellbeing of the civilian population hostage, giving the international community the poisoned choice of abandoning people in need or propping up the Houthi state. The group has been able to marshal humanitarian assistance to underwrite economic activity in the areas it controls, helping to legitimate its rule and freeing up resources for its war effort. Houthi security forces have successfully suppressed dissent, and an ever-growing number of children and adults are indoctrinated into the group through the rewriting of school curricula and religious teachings at mosques. The economy remained relatively stable in Houthi-held areas, even as searing inflation took hold elsewhere in the country. Its apparent success has furthered the group’s zealotry and sense of impunity, both on display in September with the public executions of eight men and a minor in Sana’a. In sum, the Houthis’ theocratic state-building project continued to gain steam through 2021.

As the year wore on, non-Yemeni stakeholders appeared to abandon hope that Houthi leaders were serious about peace talks. Riyadh has now spent several years trying to extricate itself from its military intervention in Yemen but has been unable to negotiate a settlement. In Washington, President Biden appointed a special envoy for Yemen in February to spearhead US diplomatic efforts to halt the conflict, but to little effect. United Nations Special Envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths, having seen his Joint Declaration proposal for a nationwide cease-fire fail, left to become the UN’s head of humanitarian affairs in May. His successor, Hans Grundberg, assumed the post in September, making the grim assessment that he expected “no quick wins”.

Then, in late November 2021, came news that the Joint Forces were redeploying from their long-held positions south of Hudaydah city on Yemen’s Red Sea coast, and the shape of the conflict very quickly began to change.

In 2018, the United Arab Emirates took the lead in organizing, arming, training and funding three armed groups: the National Resistance Forces, led by Tareq Saleh; the Giants Brigades, consisting mostly of southerners and led by Salafis; and the Tihama Resistance, a local armed group from Yemen’s west coast formed early in the conflict. Collectively known as the “Joint Forces”, they spearheaded a push up the Red Sea coast to liberate the Houthi-held Hudaydah city, home to the country’s busiest port. The UN and international aid agencies decried the assault, arguing that the disruption to commercial and humanitarian imports would spark widespread famine. Saudi Arabia acceded to the pressure, forcing the UAE-backed forces to halt their advance on the southern outskirts of Hudaydah. This localized armistice was then formalized by the December 2018 Stockholm Agreement. In 2019, Abu Dhabi drew down most of its military investment in Yemen, while maintaining its patronage of the Joint Forces, which remained stationed on the west coast.

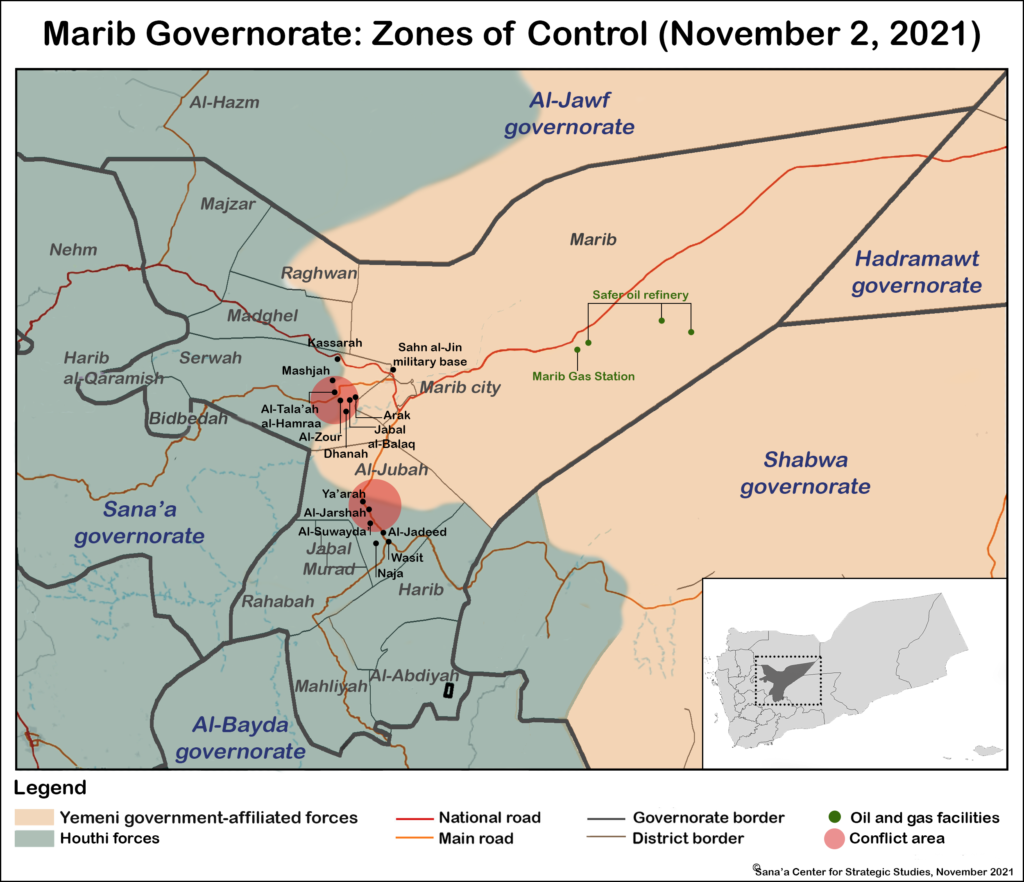

The sudden redeployment of the Joint Forces in November was unexpected and its initial motivation unclear. But then the Giants Brigades began to engage Houthi forces in Shabwa and southern Marib in late December and early January 2022, erasing Houthi aspirations for an imminent takeover of Marib city. Better trained, armed and coordinated than any force the Houthis had faced in their two-year push toward the city, the Giants Brigades accumulated a series of quick victories, retaking territory and cutting Houthi supply lines. That the Emirati-backed forces proved so effective, particularly relative to Saudi-backed groups, was both a source of relief and wounded pride in Riyadh; the most effective military push against Houthi forces since 2018 was again spearheaded by the kingdom’s much smaller neighbor. In Western capitals, the results of the redeployment made clear the respective organizational and military capabilities of the two Gulf states. The Giants Brigades’ string of victories upended the most significant Houthi military initiative of the past two years, in which the group has lost tens of thousands of fighters, dealing a blow to propaganda claiming a divine right to rule. The Houthi drone strike on Abu Dhabi in early January 2022 was not just to impose a cost on the UAE for its re-engagement, but a message to Houthis’ domestic audience, projecting an image of strength after a series of stinging setbacks.

Though the Houthi advance had stalled, the party that fell the farthest in stature and power in 2021 was Islah, particularly after the reengagement of the UAE. As the Yemeni affiliate of the regional Muslim Brotherhood, which Abu Dhabi deems a terrorist organization, Islah has been an Emirati target during the coalition’s intervention, even though it is ostensibly on the same side. A condition of Abu Dhabi’s reengagement was that Riyadh agreed to facilitate the sacking and replacement of the pro-Islah governor of Shabwa, which happened in late December. The speed with which the Giants Brigades racked up victories against Houthi forces in Shabwa, forcing them out of the southern governorate, underscored for many the ineptitude and corruption that had prevented Islah from mounting an effective resistance. Islah’s closest ally in the government, Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, has clearly fallen in standing and appears destined for replacement in 2022. President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, another key Islah ally, appears to be weaker, both politically and in terms of his physical health, than at any other time in the conflict. The party’s only bright news came from abroad, with Saudi Arabia and Qatar, the main Gulf backer of the Muslim Brotherhood, mending their years-long feud. But Islah has never looked weaker in Yemen, and the party’s prospects have appreciably dimmed.

Islah’s primary domestic rival, the Southern Transitional Council (STC), fared better in 2021. A secessionist party used to being in opposition, its participation in the national unity government has been predictably uncomfortable. The STC has had to parse the hypocrisy of attending cabinet functions while rallying its supporters to protest the government and demand a separate state in South Yemen. But in the latter half of 2021, the currency collapsed in areas outside of Houthi control, and the STC’s de facto rule over Aden and other southern areas exposed the group to growing public anger. Backed by the UAE, the STC benefited from Emirati reengagement and the removal of the pro-Islah governor in Shabwa, where the STC was defeated by pro-government forces in 2019. By year’s end, the STC was welcome in both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, and managed to increase its stockpile of money, weapons and political support.

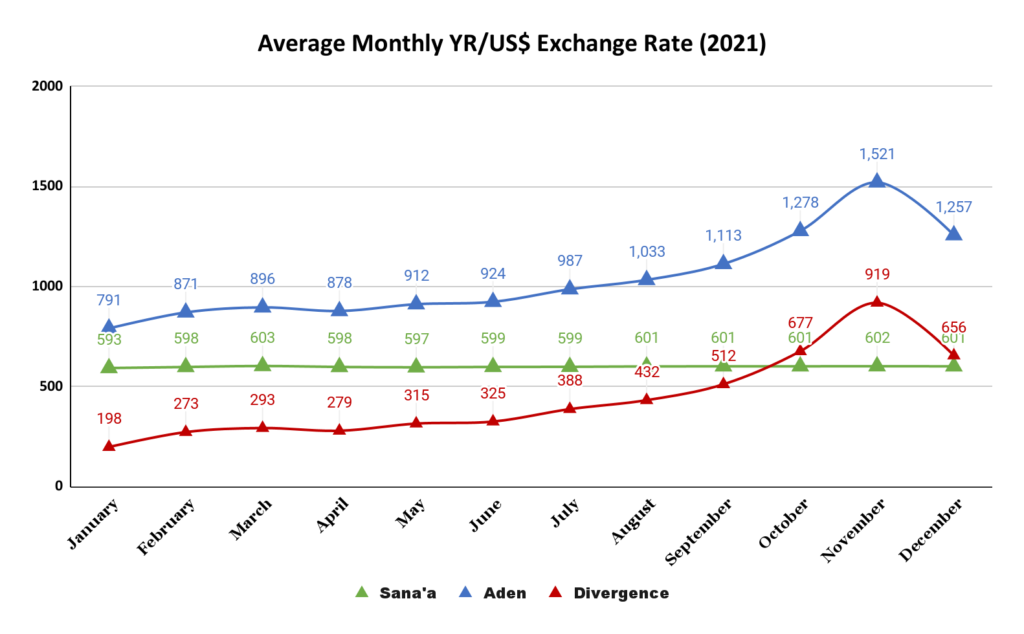

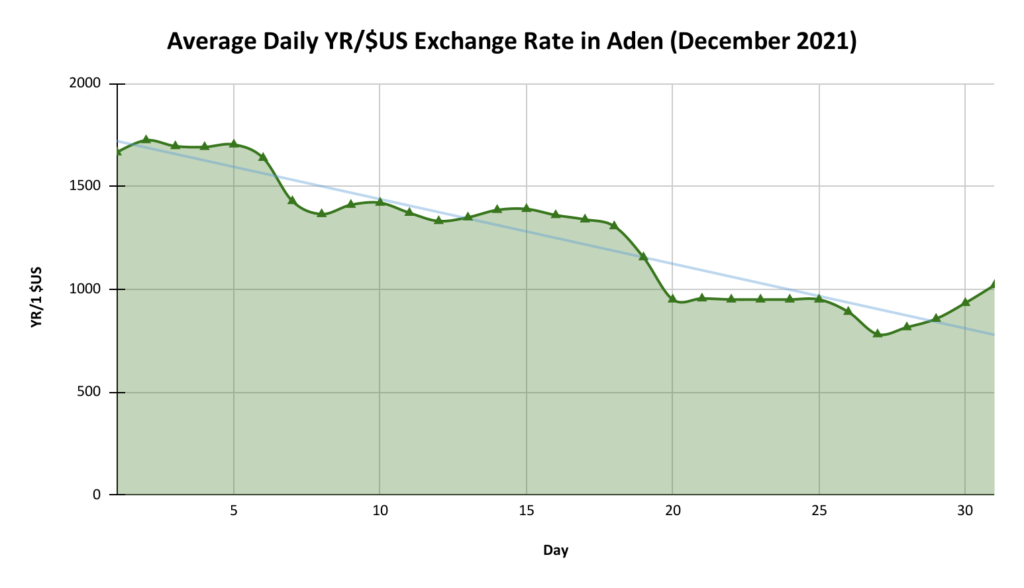

Away from the battlefield, the rapid collapse of the Yemeni rial in non-Houthi areas posed an existential threat to the government. The remnants of the government’s legitimacy could be felt evaporating with the currency’s plummeting value, which led to protests that threatened to dissolve what remained of social and political order. But just as Emirati reengagement dramatically reshaped the conflict, so did the government’s decision to sack the senior leadership of the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden). The bank has long faced accusations of mismanagement and massive corruption – including by the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen in January – and the threat of further graft has been a major obstacle to securing desperately needed financial support. Following the announcement of new leadership at the bank in early December, accompanied by reports that Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries were considering renewing financial support to the bank, the Yemeni rial began a dramatic recovery. While the currency remained unstable, it held onto most of its December gains as 2022 began, with the market clearly pricing in its support of the new administration and the prospect of new external financial assistance. Should the rial’s recovery continue, it would be a dramatic step forward for economic stability, the humanitarian situation and the government’s legitimacy.

Had Houthi forces taken Marib, along with its oil and gas resources, the group would have secured the economic resource base for its de facto state and emerged with even less incentive to negotiate. The diplomatic track will remain fraught in the near term, however, as the redeployment of the Joint Forces increases the probability that other, long-dormant frontlines become active and push peace talks further off the table. Houthi drone and missile strikes against the UAE also threaten further regionalization of the Yemen war.

But the door is still open for common ground and compromise on the dire economic crises the country faces, which negatively impact far more Yemenis than the immediate violence. Diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict have yet to gain traction; there was little incentive for the Houthis to come to the table while their military successes continued. As the war enters its eighth year, the prospect of an economically strengthened Yemeni government, and a possibly chastened Houthi leadership, may offer the UN special envoy and other international stakeholders new avenues for mediation.

Executive Summary

Part I: The Year in Politics

Open warfare between the Yemeni government led by President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and its new junior partner, the Southern Transitional Council (STC), largely quieted in 2021, but their relationship never evolved into a partnership of governance. The fallout from this divide — combined with distrust and hostility that weakened the Islah party, the other key partner within the Hadi government — contributed to the government’s inability to cohesively address a rapidly deteriorating economic situation. As the Yemeni rial plummeted in value throughout 2021, popular protests against rising fuel prices, electricity outages and unpaid salaries roiled southern and central Yemen (see: ‘Declining Currency, Living Standards Spur Unrest’).

In March, one protest, backed by the STC, led to the storming of Aden’s Ma’ashiq Palace, the seat of government. In Hadramawt, on March 30, security forces west of Mukalla city fired on demonstrators, killing one civilian, and leading to the declaration of a state of emergency by Hadramawt’s governor. Protests also occurred in Taiz, beginning in late May, against the local governor, and in mid-September large demonstrations broke out across southern Yemen.

Protesters did not spare the Hadi government’s smaller factions in areas where they dominated local authorities. While the STC painted itself as supportive of the protests, it also cracked down on some of them in Aden; the demonstrations of 2021 were largely a grassroots effort to express outrage at Yemen’s political elites, whatever party or movement they belonged to. Popular protests in Shabwa escalated dramatically against the pro-Islah local authority in the final months of the year; accusations of corruption and poor performance on the battlefield combined with the economic pressure. Ultimately, Hadi fired Shabwa’s pro-Islah governor, Mohammed bin Adio, on December 25. Awadh bin al-Wazir al-Awlaqi, a tribal leader and General People’s Congress member of parliament, replaced him. Al-Awlaqi had been living in the UAE before returning to Shabwa to lead the protest movement (see: ‘The Shabwa Protest Movement and Bin Adio’s Fall’). The turnover highlighted Islah’s diminishing status politically as well as militarily, and furthered the STC-UAE ascent.

The STC’s confidence grew through the year, in part owing to its ability to capitalize on the political and military misfortunes of the Islah party and the more active involvement of the UAE. The return to Aden in May of STC leader Aiderous al-Zubaidi showcased the group’s confidence in its position in the government’s interim capital, and the STC’s leadership was not willing to compromise with the government to implement the remaining provisions of the December 2019 Riyadh Agreement that gave them a formal share of power. Both the government and the STC have obstructed implementation of provisions such as the appointment of new governors for most southern governorates, the redeployment of the majority of government and STC armed forces away from Aden, and the incorporation of STC military and security units into the ministries of Defense and Interior (see: ‘Status Update: The Riyadh Agreement’).

The inclusion of STC members in the Yemeni cabinet was a provision of the Riyadh Agreement, which had been implemented in late 2020. Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed had declared three priorities at the start of the new administration: reform of the economy; an end to the deterioration of the currency; and a fight against corruption. However, the prime minister often worked from outside Aden during the cabinet’s first year and, even when based in Yemen, the government was largely ineffective (see: ‘A ‘Unity Cabinet’ with Myriad Problems, Minimal Presence’).

While Saeed has been largely unsuccessful in implementing policies that would solve some of the economic problems crippling Yemen, he has sought to establish some independence from President Hadi; there has been notable friction between the two, according to political insiders. Saeed represents a separate power center in the government, with his rise coming at the expense of Hadi and Islah. A large part of this has been thanks to Saeed’s own good relations with Saudi Arabia and UAE, the latter which he has visited, unlike Hadi.

Houthis Focus on Consolidating their Position as a Governing Authority

The Houthis have taken advantage of being relatively secure in the areas under their control to focus on entrenching their rule and with it a quasi-restoration of the Zaidi Imamate that ruled northern Yemen prior to 1962. The Houthis’ multi-pronged approach to this focused on education, persecution and the consolidation of power in the hands of Houthi loyalists (see: ‘Houthis Shore Up Mechanisms of State’).

Through the educational system they control in northern Yemen, the Houthis have been able to indoctrinate young people in their ideology. They have changed the curriculum to emphasize concepts such as “defending the homeland” and the history of Yemen’s Zaidi imams. Additionally, the movement has employed extra-curricular education programs to preach their ideology to children, and, as local human rights organizations have argued, to recruit fighters (see: ‘Educational Indoctrination and Child Recruitment‘).

Emboldened with their success on the frontlines through much of 2021, the Houthis were able to persecute rivals with impunity, even civilians of whom they disapproved. In February, a Yemeni model, Intisar al-Hammadi, was detained along with three other women. Ignoring the criticism this unleashed on social media and from human rights organizations, the Houthis sentenced the women in November to up to five years in prison for indecency. An even more chilling event took place in September, when eight men and a teenager were publicly executed in the center of Sana’a, after being found guilty by a Houthi court of their involvement in the April 2018 drone strike that killed then-president of the Houthis’ Supreme Political Council, Saleh al-Sammad. The men were tortured during their time in detention, and the teenager, Abdulaziz Ali al-Aswad, was partially paralyzed by the time of his execution (see: ‘Consolidating Power, Spreading Fear’).

The Houthis also began to install more of their loyalists, particularly those from Sa’ada, in high-ranking ministerial positions. The Houthis had previously allowed non-Houthis to assume figurehead positions with Houthi loyalists in behind the scenes positions, but this appears to be changing. While some details of tensions within the Houthi movement have emerged, the group appeared to still be fairly united in its goals, and the reality is that it long has been difficult to glean much in the way of reliable information on the leadership dynamics within the Houthi movement (see: ‘Houthi State-Building and the War Effort’).

Regional Actors’ Interests, Houthi Disinterest Complicate De-escalation

Anti-Houthi coalition members may all consider the Houthis to be their opponent, but it is hard to argue that they are on the same side. Throughout 2021, the UAE and Saudi Arabia appeared to be seeking to minimize the Saudi-led coalition’s role in the conflict, while protecting their own specific interests (see: ‘UAE Proxies Allow for Continued Influence’). The first controversy was over the island of Mayun (also known as Perim), in the Bab al-Mandab Strait, where UAE forces were present and an airbase was being built. Although the Saudi-led coalition publicly stated that positions in Mayun were being used to support anti-Houthi forces on the Red Sea coast, the UAE’s broader political and economic goals have seen it focus on situating bases along oil and commercial trade corridors. Its presence in Mayun as well as Socotra, where it also has a base, merely exacerbated concerns about the implications for Yemeni sovereignty.

Saudi Arabia, the senior partner in the regional military coalition, was looking for a way out of the war in Yemen throughout 2021 that would prioritize its national security interests, perhaps over the interests of the kingdom’s local allies. In March 2021, Riyadh presented a new peace proposal that involved the lifting of the Saudi-led coalition partial blockade of Hudaydah port, the reopening of Sana’a International Airport, and peace talks among the Yemeni parties involved in the conflict. It was quickly rejected by the Houthis, who insisted the proposal was “nothing new”, but discussions between the two sides continued for the rest of the year, aided by Omani mediation and parallel to Saudi Arabia’s own de-escalation talks with Iran (see: ‘Attempts at Saudi-Iranian Deescalation’).

Despite the talks, Saudi Arabia faced a succession of cross-border Houthi drone and missile attacks throughout the year, mainly targeting military and oil facilities, as well as airports. These strikes, combined with the Houthis’ persistent pressure on Marib, frustrated international actors, who lacked the leverage to interest the battle-confident Houthis in a cease-fire much less in laying groundwork for a peaceful settlement.

Reassessing Strategies: International Players Seek a New Direction

On the international front, both the United States and the United Nations altered course in Yemen in 2021. Newly elected US President Joe Biden promised early in 2021 a stronger US diplomatic role and support to UN cease-fire and peace negotiation efforts (see: ‘Yemen and the US Under the Biden Administration’). He quickly appointed a veteran State Department official, Timothy Lenderking, as US special envoy to Yemen and overturned a last-minute Trump administration designation of the Houthis as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO), hoping to facilitate negotiations. By mid-year, however, the US was “beyond fed up” with Houthi intransigence and “horrified by the repeated attacks on Marib;” by early 2022, Biden was considering reimposing the FTO designation. At the UN, Martin Griffiths, the UN special envoy since February 2018, gave a final, futile push for his Joint Declaration initiative, which was intended to instill a cease-fire, improve the economic and humanitarian situation and provide a framework for peace talks. Griffiths then left the envoy post in mid-2021, taking up a new senior UN position as under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs, replacing Mark Lowcock (see: ‘Yemen and the UN: Dead Ends and Fresh Starts’).

The UN tapped Swedish career diplomat and European Union envoy to Yemen, Hans Grundberg, in August to take over for Griffiths. Grundberg spent weeks meeting with local, regional and international actors before briefing the UN Security Council in December and sketching out his intended approach. Grundberg prioritized deescalation and, in a departure from his predecessor, economic relief; he also urged the warring parties to talk, even if they continued their battles on the ground. Although Grundberg met with many parties inside Yemen, including the Southern Transitional Council, Hadi government officials, military figures, civil society organizations and local government officials, he had not visited the Houthi leadership in Sana’a by the end of the year.

The UN humanitarian response in Yemen, meanwhile, scaled back programs, citing funding shortages as pledges failed to keep pace with recent past years. Donor skepticism combined with pandemic-related economic concerns to hit funding levels hard in 2020, when the UN received US$2 billion (59 percent of its appeal) and recovery was slow in 2021, when US$2.24 billion was received (58 percent of the requested amount). The shortfalls prompted cuts to food, health, clean water and other programs, and warnings of more to come (see: ‘UN Donor Conferences and Humanitarian Funding’).

For complete coverage and analysis of political developments in Yemen in 2021, including local, regional and international actors’ roles, see the full section, Part I: The Year in Politics, which includes:

- Political Developments in Government-Held Areas

- A ‘Unity Cabinet’ with Myriad Problems, Minimal Presence

- STC Struggles with Balancing Act

- Yemeni Parliament Fails to Reconvene

- Declining Currency, Living Standards Spur Unrest

- The Government-STC Conflict in Shabwa

- Islah: In Search of Allies

- Saleh’s Forces Enter the Political Fray

- Eastern Power Struggles: Al-Mahra, Socotra and Hadramawt

- Politics and Governance in Houthi-Held Areas

- Regional and International Developments in 2021

Part II: Military Developments in Yemen

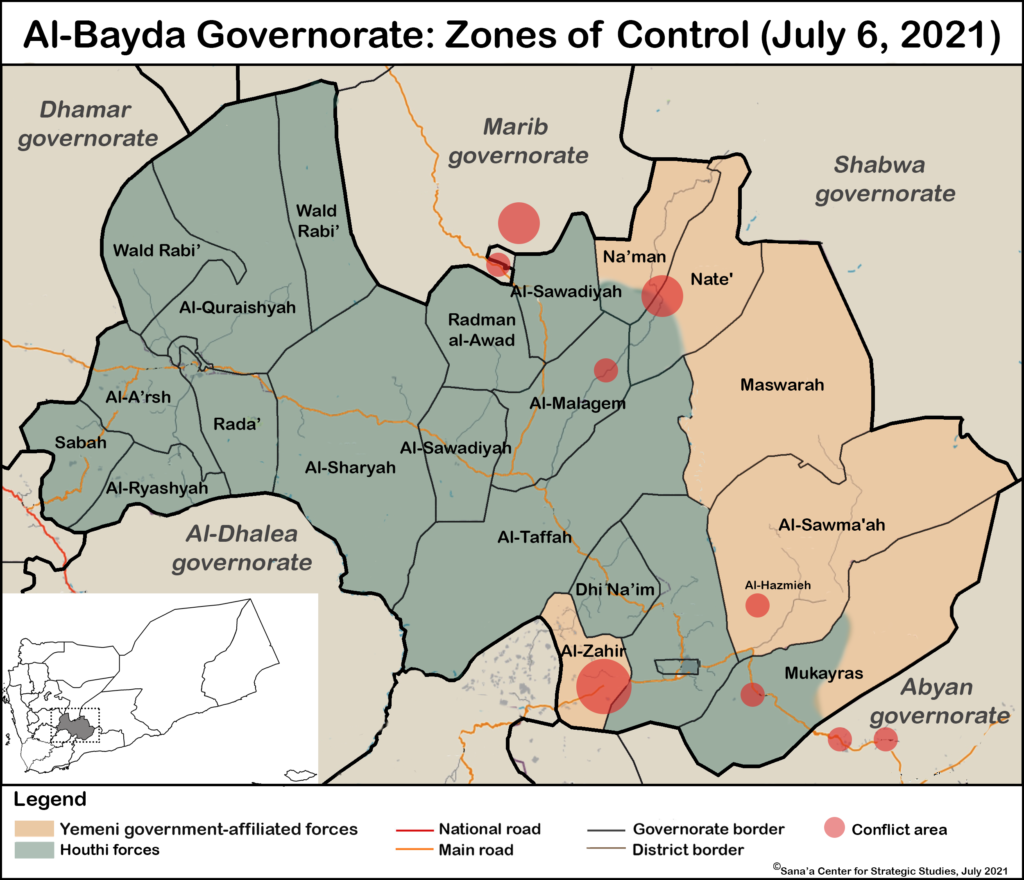

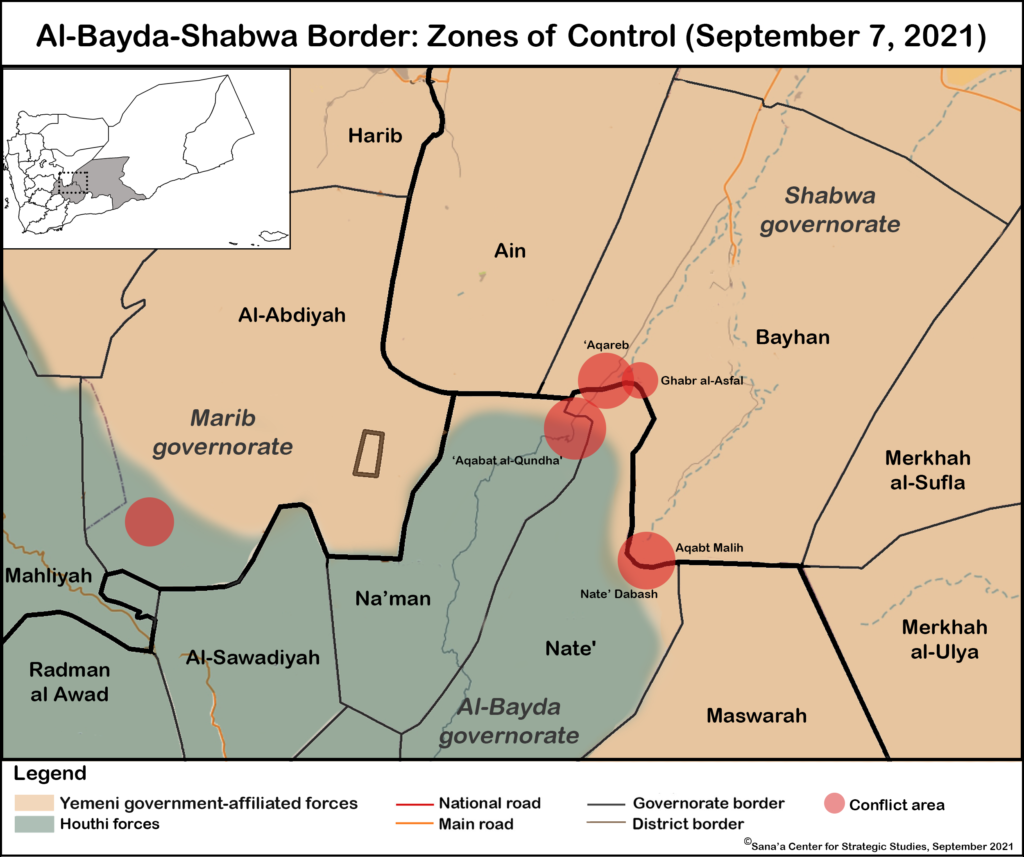

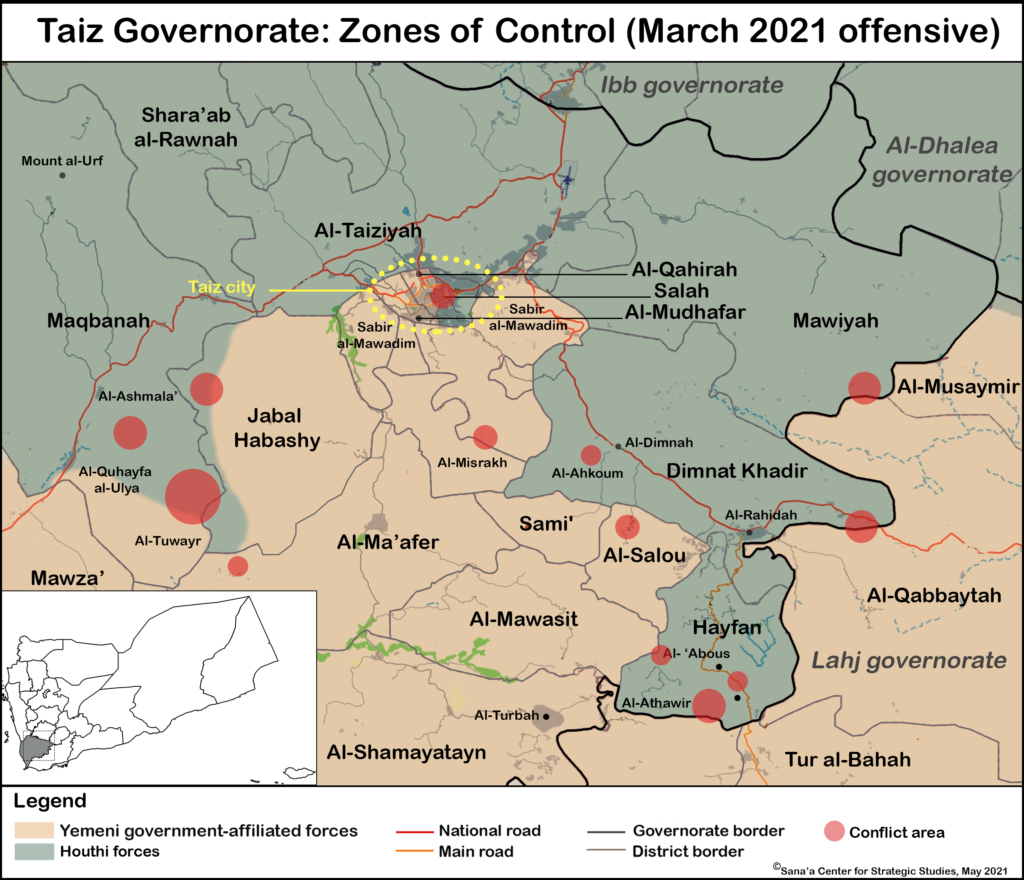

On Yemen’s battlefields, it is hard to argue that 2021 was anything other than a year of victories for the armed Houthi movement. In Marib, Houthi forces advanced on Marib city from the west and the south, taking control of the heartlands of the main government-allied tribes fighting them. In Al-Jawf, the Houthis pushed government forces almost entirely to the governorate’s eastern deserts, leaving only one base still precariously in the hands of government forces. In Taiz, a government offensive designed to take the pressure off forces defending Marib eventually led to a Houthi counterattack, in which the latter took back many of the areas lost. That scenario was repeated, to greater effect, in Al-Bayda, where government forces set out to capture a key city only to lose the entire governorate, positioning the Houthis well for some of their most dramatic advances on the ground in recent years (see: ‘How the Govt Offensive in Al-Bayda Backfired, Jeopardizing Marib’). Even in Shabwa, in Yemen’s south, the Houthis were able to seize three districts, their first victories in the hydrocarbon-rich governorate before being forced out at the turn of the new year.

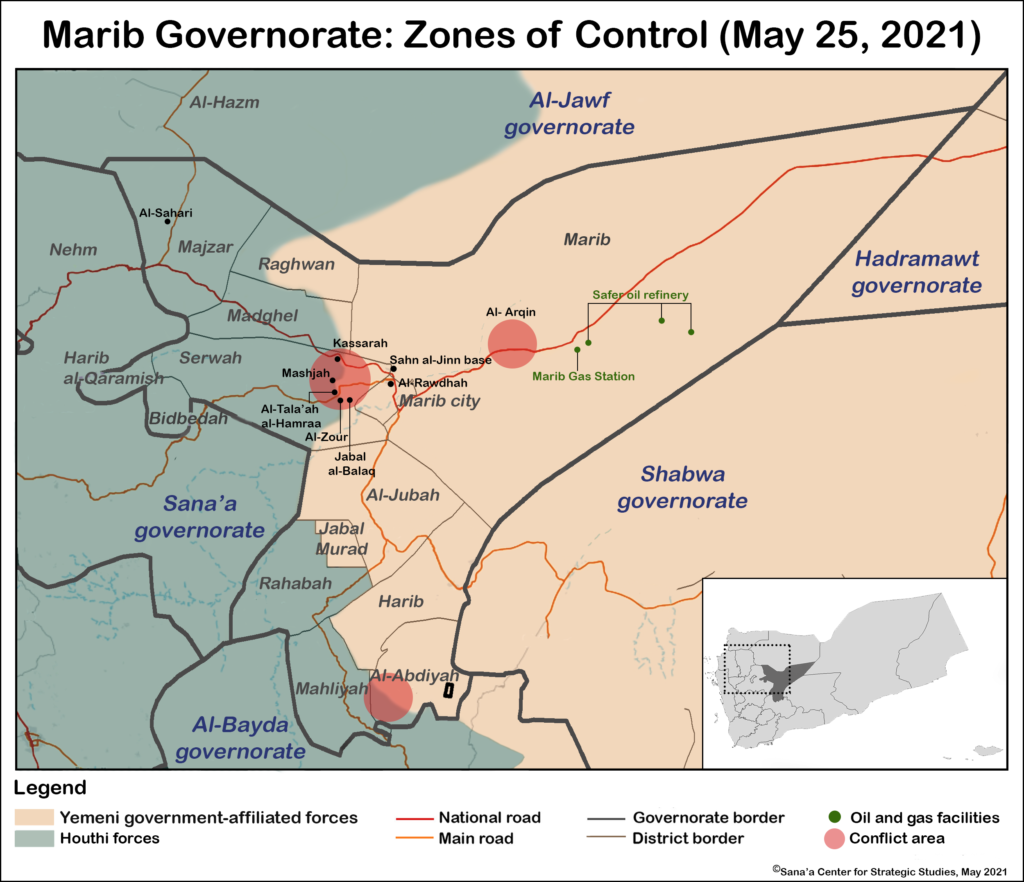

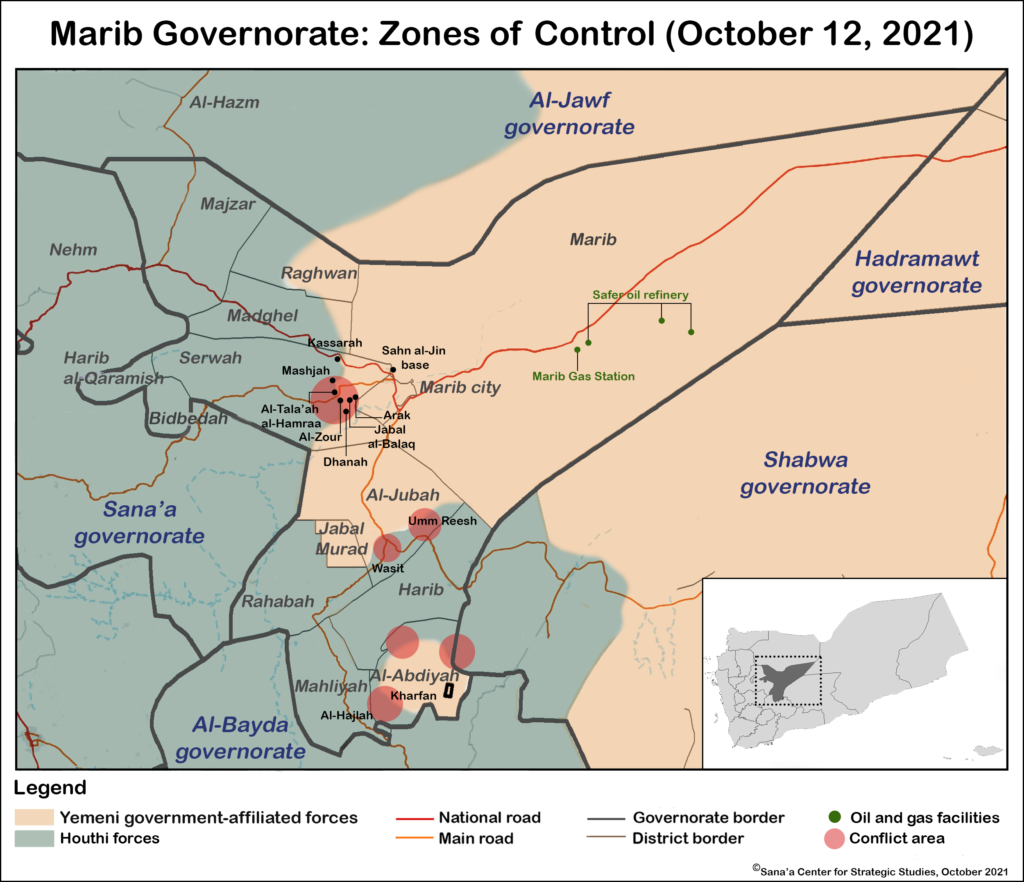

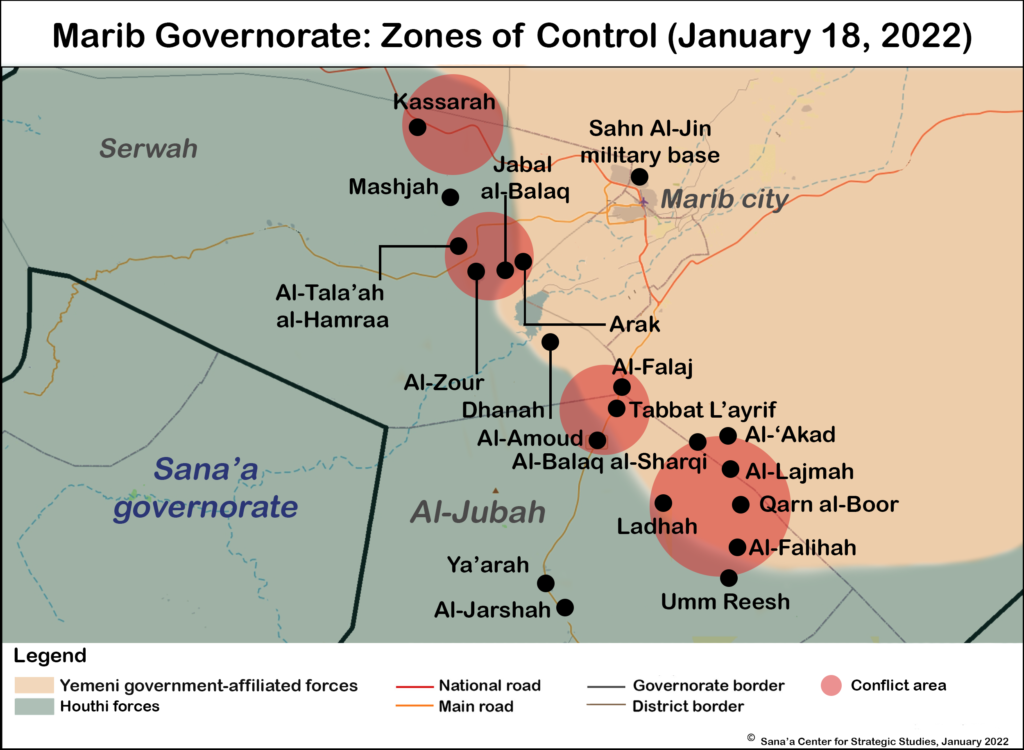

The Houthis benefited throughout 2021 from their cohesiveness, their ability to continually send a greater number of fighters to the frontline and divisions among their opponents. A case in point is the battle for Marib (see: ‘The Road to Marib City’), the government’s main stronghold in northern Yemen, where tribal fighters supported by government troops struggled to keep Houthi forces at bay. A February offensive brought the Houthis to the Balaq mountains, the gateway to Marib city from the southwest, prompting a wave of displacement as families fled frontline areas (see: ‘The Other War: Missile Strikes, Assassinations and Displacement’). While that offensive stopped there as a result of the excellent defensive position the Balaq mountains gave government defenders, the Houthis later found another route from which to push toward Marib city.

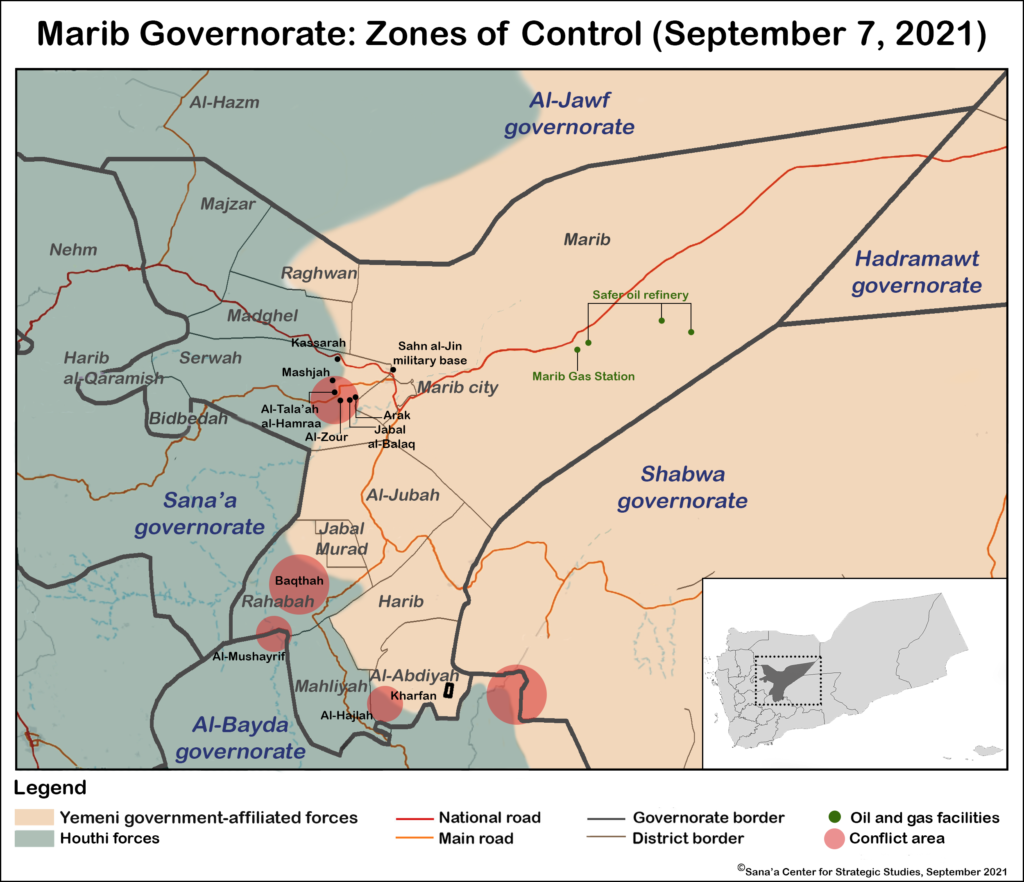

Southern Marib is the home of the Murad and Bani Abd tribes, the backbone of pro-government forces fighting in the governorate. However, after years of fighting, the deaths of hundreds of tribesmen, and complaints about the lack of salaries and effective support from the government and Saudi-led coalition, the tribal areas of Al-Abdiyah, Al-Jubah and Jabal Murad fell to the Houthis in quick succession in October 2021 (see: ‘The Southern Offensive’). The advance brought the Houthis within 15 kilometers of Marib city, as close as they would come in 2021 to conquering a city coveted as a game-changer before Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates shook up the anti-Houthi coalition’s military strategy.

Islah’s Fortunes Fade: Left Out of Marib, Marginalized in Taiz, Replaced in Shabwa

While gleaning information about the inner workings of the armed Houthi movement remained difficult as ever in 2021, it clearly maintained a broadly united force. Despite heavy casualties sustained throughout the year, the Houthis were able to recruit and send more fighters to the frontlines, including child soldiers (see: ‘Child Soldiers in Yemen’). In stark contrast to the Houthis’ united front, Yemen’s anti-Houthi forces were riven by divisions, the impact of which clearly was felt on the frontlines.

Supporters of the Islamist Islah party long have dominated government military forces in Marib, Taiz and Shabwa governorates. Opponents of Islah within the coalition, therefore, blamed the party for the poor performance of those military forces in 2021, accusing the group of focusing on its own goals rather than cooperating with others. For their part, pro-Islah media and political figures have accused the United Arab Emirates of undermining Yemen’s sovereignty and sowing division within the anti-Houthi coalition by backing paramilitary forces aligned with the secessionist Southern Transitional Council (STC). Saudi and Emirati priorities as well as the key regional powers’ distrust of some of their local partners on the ground also complicated the military campaign throughout the year.

Islah supporters maintained that the Saudi-led coalition did not properly back government forces fighting in Marib. Salary payments to government soldiers in Marib were notoriously late, and often not paid in full; whether the coalition was providing government forces in Marib the weapons they needed also was a point of contention. At the same time, offers by Tareq Saleh, the leader of the UAE-backed Joint Forces, to have his troops help fight the Houthis in Marib were rejected. In Taiz, when the pro-Islah Taiz Military Axis carried out an offensive against the Houthis in March, there was little support from the Joint Forces or the Saudi-led coalition. The coalition even refused to provide weapons to Islah-affiliated government forces lest those weapons be used in the future against Saleh, who maintains good relations with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi (see: ‘The Taiz Front’). It was little surprise, then, when a Joint Forces’ offensive against the Houthis in western Taiz later in the year received no support from the Taiz Military Axis.

In late September, when Houthi forces crossed from Al-Bayda governorate into Shabwa, a stronghold of the Yemeni government in southern Yemen, Islah-aligned government forces soon withdrew. This allowed the Houthis to gain control of Ain, Bayhan and Usaylan districts in northwestern Shabwa, from where they were able to mount their second big push toward Marib city in 2021 (see: ‘The Bayhan Offensive and Its Aftermath’).

Islah’s quick retreat prompted accusations from its political opponents, most notably the Southern Transitional Council (STC), of a Houthi-Islah conspiracy. Shabwa governorate had seen confrontations between the Islah-affiliated local administration and STC supporters throughout 2021, despite the presence of pro-STC, UAE-backed Shabwani Elite forces being limited to the Balhaf LNG terminal and Al-Alam military camp. Shabwani Elite members were detained at several points in the year by local government forces, and the tension between the two sides culminated in a stand-off over Al-Alam after the UAE withdrew from the camp in October. Pro-government forces ultimately took Al-Alam by force on October 30 (see: ‘The Conflict in Shabwa’).

Despite that success against the STC, Islah’s power in Shabwa had been intrinsically weakened by the loss of northwestern Shabwa to the Houthis. It was units from the UAE-backed Giants Brigades, a constituent of the Joint Forces brought in from the Red Sea coast and backed by a coalition air campaign, that ultimately forced the Houthis out of Shabwa. By the time the dust had settled in January 2022, Islah had lost both political control and military dominance in Shabwa, and members of the disbanded Shabwani Elite were reactivated, reconstituted and rebranded as the Shabwani Defense forces.

Eyeing the Exits? Coalition Redeployments and the Hudaydah Withdrawal

The UAE withdrawal of its forces from Al-Alam camp and other positions in Shabwa came within weeks of Houthi forces entering the governorate’s northwestern districts. Saudi forces had already withdrawn from positions in Al-Mahra, Aden and Hadramawt governorates. Although the Saudi-led coalition described the troop movements as redeployments rather than withdrawals, they added to speculation that the coalition was preparing for an exit from Yemen (see: ‘Coalition Shifts’).

Another withdrawal — the coalition-backed Joint Forces’ unilateral retreat from large swathes of Hudaydah governorate, including Hudaydah city — also raised questions, even within the Joint Forces’ ranks (see: ‘The Hudaydah Front: Ceding Ground to the Houthis’). Regular bouts of fighting persisted even though there had been little movement on the frontlines in Hudaydah for much of 2021. It was, therefore, surprising when the Joint Forces unilaterally withdrew 90 kilometers south from Hudaydah city to Al-Khawkhah district. The Joint Forces’ leadership linked the decision to withdraw to the 2018 UN-brokered Stockholm Agreement, which ended a coalition offensive on Hudaydah city, explaining that any advance by the Joint Forces in Hudaydah city and its environs would lead to accusations that the forces were obstructing implementation of the deal. The fact that the withdrawal came three years after the agreement raised eyebrows, and the withdrawal was confused, with some fighters criticizing the decision to abandon territory they had fought to gain. The Joint Forces eventually established new positions in southern Hudaydah governorate and from there launched fresh offensives in southeastern Hudaydah and northwestern Taiz governorates. These petered out in December, however, as UAE-backed Giants Brigade units redeployed to Shabwa to counter the Houthi advance there.

If the UAE and Saudi Arabia had withdrawn their forces as steps toward extricating themselves from the Yemen War, leaving behind a multi-sided civil war, they were effectively pulled back in by the Houthi presence in Shabwa and threat to Marib. The final weeks of 2021 required hands-on strategic involvement of Abu Dhabi and Riyadh, not to mention significant coalition air support, to execute an effective counterattack against the Houthis. The UAE itself, despite its announced military withdrawal from Yemen in 2020, exerted significant influence in 2021 that was arguably growing at the start of 2022. With the UAE-backed Giants Brigades leading the fight against the Houthis on the battlefield, it was clear that the pendulum had swung sharply away from Islah to UAE-supported forces in Shabwa. This was compounded by the quick and effective performance of the Giants Brigade forces in early January 2022; backed by coalition airstrikes, they were able to push the Houthis out of Shabwa in less than two weeks.

While Islah would argue that its allies within regular government forces would have had the same successes with the same coalition support, it appeared likely that Islah’s opponents would take charge in 2022 of the fight against the Houthis in Al-Bayda, and potentially in Marib. Whether the UAE would lend the same support as it did in Shabwa remained to be seen. The Houthis, their march on Marib having sustained a serious blow, were unhappy with the UAE’s reemergence on Yemen’s frontlines; they made that abundantly clear at the start of 2022 with a drone attack on Abu Dhabi International Airport that killed three people.

For complete coverage and analysis of military developments in Yemen in 2021, see the full section, Part II: Military Developments in Yemen, which includes:

- The Road to Marib City

- Failed Government Offensives

- Intra-Coalition Flashpoints

- Coalition Shifts

- The Air War

Part III: Economic Developments

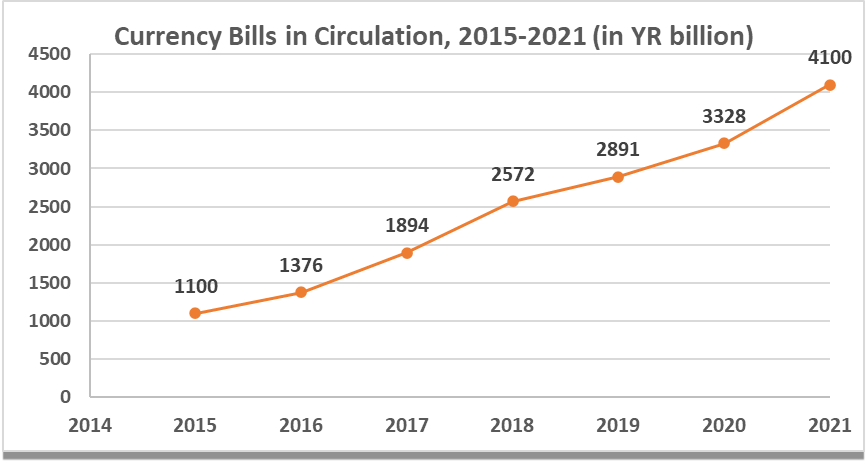

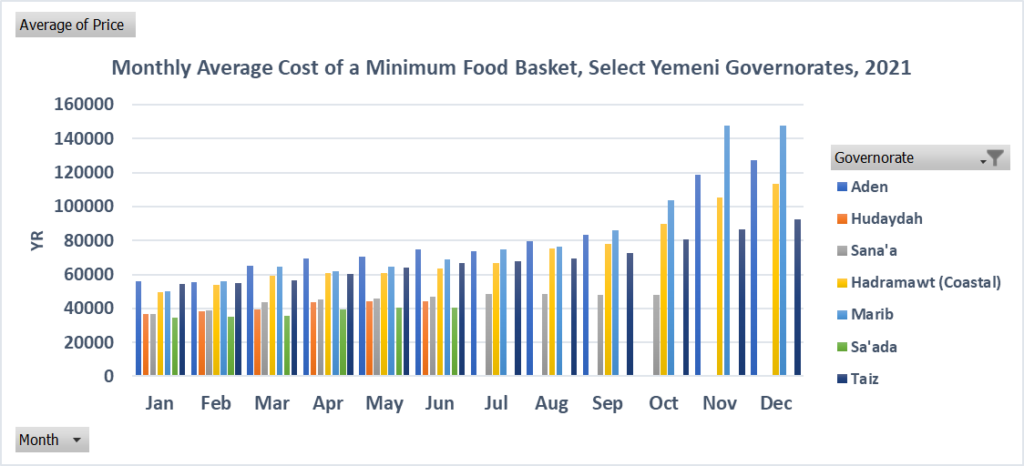

Among the most important economic developments in 2021 was the dramatic depreciation of the Yemeni rial (YR) in government-controlled areas, followed by its just-as-dramatic recovery as the year ended. This caused rapid price spikes, declining living standards and civil unrest, particularly from August through November. A primary factor in the rial’s decline has been that the Yemeni government, facing massive budget shortfalls, has continued to monetize the public deficit by having the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden print new rials to cover recurrent expenses, largely public sector salaries. The increasing supply of domestic currency in government-held areas has been exacerbated by dwindling hard currency stocks. This comes in sharp contrast to northern areas where Houthi authorities have largely abdicated their responsibility for paying civil servant salaries while continually strengthening their revenue collection through customs, taxes and coercive fee collection. Controlling the majority of the Yemeni population and business centers, the Houthi authorities also benefit from the economic leverage of having most of the country’s current foreign currency inflows, in the form of remittances and humanitarian aid funds, arriving in areas the group controls. Other contributing factors behind the depreciation of the rial in government areas include the escalating struggle over monetary policy with the Houthi-controlled Central Bank of Yemen in Sana’a (CBY-Sana’a), and Houthi battlefield advances, which undermined faith that currency printed by the government-run Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) – which the Houthi authorities have banned – would maintain its value. The potential implementation of an electronic currency and e-payment ecosystem was increasingly contested, with Houthi authorities and CBY-Sana’a attempting to push forward a minimally regulated model that largely circumvents the formal banking sector, while the Yemeni government and the CBY-Aden sought to oppose these efforts, and adhere to the pre-conflict legal mandate for a highly regulated, bank-led system.

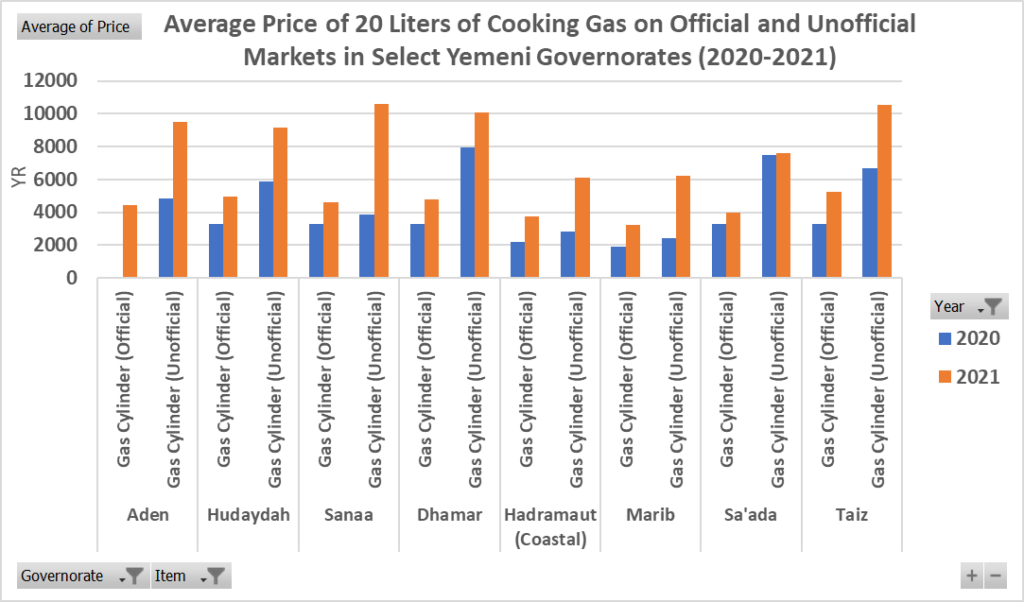

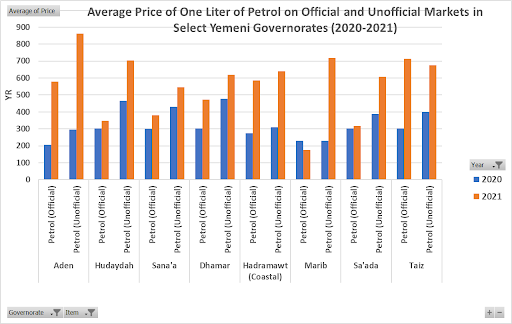

The tussle for economic preeminence between the warring sides continued across the various sectors in 2021. This included a struggle over fuel imports, with the Yemeni government significantly reducing clearances for commercial fuel shipments through the Houthi-controlled port of Hudaydah, redirecting them to its own ports where it could collect customs revenue. Traders quickly adapted their supply chains, trucking fuel overland to Houthi-controlled areas in sufficient quantities – based on import data and anecdotal evidence – to keep the overall supply of fuel stable in Houthi areas. However, Houthi market manipulation and a second layer of customs tariffs imposed at land crossings led to price spikes and fuel shortages in northern areas, which Houthi authorities then used to build international pressure against the government’s policies. Houthi authorities and the Yemeni government have also both raised their respective customs duties on many non-fuel commodities. Higher tariffs and higher fuel prices left millions of Yemenis facing prices for basic commodities they could ill afford.

Civil servants in Houthi-controlled areas saw only minimal salary payments in 2021. Most workers on the Yemeni government payroll, meanwhile, received their monthly salaries regularly, though their value was rapidly eroded throughout the year as the Yemeni rial depreciated in government-held areas. Exceptions to this were various military units in southern Yemen, mostly affiliated with the Southern Transitional Council (STC), which have not seen regular salary payments since 2020 due to issues related to the stalled implementation of the Riyadh Agreement between the STC and Yemeni government. Other major economic developments also included the United States continuing to target the Houthi movement and affiliated actors with sanctions, and one of Yemen’s largest telecommunications operators, MTN Yemen, selling its shares to an Omani company suspected of being a Houthi front.

For complete coverage and analysis of the economic situation in Yemen in 2021, see the full section, Part III: Economic Developments, which includes:

- From Fragile to Failing: Economic Developments Pre-Conflict to 2021

- Dramatic Exchange Rate Depreciation in Govt-Held Areas

- Fuel Market Dynamics and Oil Production

- Public Sector Salaries

- Uncertainty Surrounds Remittances and Expat Expulsion from Saudi Arabia

- US Sanctions Against the Houthis and Affiliated Parties

- E-Rial Developments

- Telecoms: MTN Yemen Exits Amid Controversy

Part I: The Year in Politics

After more than a year of negotiations, a government unity cabinet representing Yemen’s anti-Houthi political factions flew into Aden International Airport on December 30, 2020, to begin governing from the interim capital. Its problems began before everyone could get off the plane. Three missiles launched by Houthi forces struck the airport as passengers disembarked, killing at least 25 people and injuring more than 100.[1] The Aden airport attack presaged a difficult year for the cabinet, led by Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed, and the broader anti-Houthi coalition, backed by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Beset by economic protests and infighting over control of state institutions, the unity government, once trumpeted as the solution to the coalition’s problems, has thus far failed to effectively address the major issues facing Yemenis.

Saudi Arabia’s declining faith in the Islamist Islah party, both in terms of its battlefield capability and capacity for local governance, became increasingly apparent as the year wore on. This further complicated the perennially tense relationship between the Islah-backed government and the secessionist Southern Transitional Council (STC) as the latter increased in relative power. After grudgingly incorporating the STC into the unity cabinet, the government has become ever more beholden to it, politically and militarily. In Aden, the STC has continued to use its control of the city to consolidate authority within government institutions, which it has presented as the basis of a future southern state. At the same time, as an internal opposition movement wielding real power, the STC faces significant challenges in balancing the need to administer territory, appease coalition backers and placate its secessionist base.

In the north, the Houthis have continued to expand their control, with the movement’s intent to recast the Yemeni state and society in accordance with its Zaidi revivalist ideology gaining further momentum. Empowered by battlefield successes, the Houthi leadership has fine tuned its control over state institutions and public revenues, cracked down on competing power centers and inculcated the public with its ideology. The intensive consolidation of the de facto state’s bureaucracy entailed shifting large numbers of loyalists from the Houthi heartland of Sa’ada governorate to Sana’a. While in the past Houthi officials would be appointed to oversee non-Houthi personnel, increasingly loyalists have been installed to simply replace less-trusted members of the administration. This has ensured more direct, efficient implementation of security and bureaucratic measures and improved control through a more unified state-like apparatus which in turn has allowed for relaxation of the more visible restrictions in Houthi-held areas, such as security checkpoints.

Political Developments in Government-Held Areas

A ‘Unity Cabinet’ with Myriad Problems, Minimal Presence

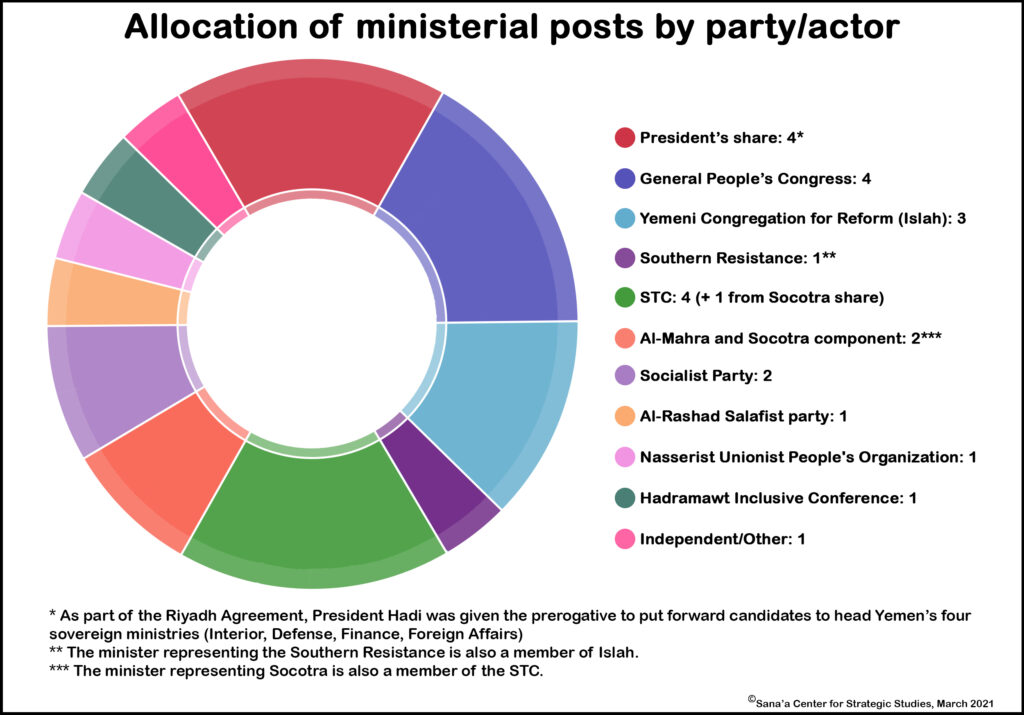

At its inception, the unity cabinet prescribed by the 2019 Riyadh Agreement (see: ‘Status Update: The Riyadh Agreement’) and announced in December 2020 in Saudi Arabia was composed of 24 ministers — 12 from northern Yemen and 12 from southern Yemen — with seats distributed among Yemen’s main anti-Houthi parties, including the STC, the General People’s Congress (GPC) and the Islah party. Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed identified the unity cabinet’s top priorities at the outset: “reform the economy, stop the deterioration of the currency and fight corruption.”[2] On top of that was an expectation that the cabinet would help mend the rift between the government of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and the STC, after more than a year of open conflict. Presenting a united political, military and diplomatic front against the Houthi movement was intended to head off disputes and obstacles any in future negotiations to end the broader war, increasing the chance for more comprehensive, lasting results.[3] A year later, it is difficult to see progress on any of these fronts.

Several challenges prevented the unity cabinet from carrying out its mandate, the most apparent being its absence from Aden for half the year. Although the cabinet was publicly committed to addressing deteriorating economic conditions and unpaid salaries, the early months of 2021 were characterized by rising fuel prices and electricity outages in government-held territory.[4] These hardships in turn gave rise to persistent and widespread protests (see: ‘Declining Currency, Living Standards Spur Unrest’), and on March 16, STC-backed demonstrators stormed the seat of government at Aden’s Ma’ashiq Palace.[5] While no ministers were hurt, and newly empowered Aden security director Mutaher al-Shuaibi was able to convince protesters to leave the palace compound without violence, the incident highlighted the precarious security situation the cabinet faced in Aden. Within a week, Saeed left Aden for Saudi Arabia.[6] Although several STC-aligned ministers remained in the city, others decamped to Riyadh, Cairo and other parts of Yemen. Hadi-appointed Interior Minister Major General Ibrahim Haydan later accused factions within the STC of obstructing security arrangements that would allow the cabinet to safely operate in Aden.[7] The STC denied the allegations and called for the government’s return, promising to provide the necessary security.[8]

Saeed spent most of the next six months in the Saudi capital, apart from a tour of Yemeni government-held areas in late April and early May.[9] He returned to Aden on a permanent basis in late September, following major Houthi advances in Shabwa and Marib governorates that raised concern that government strongholds across the country would fall (see: ‘The Road to Marib City’ and ‘The Conflict in Shabwa’).[10] Despite its stated emphasis on economic issues, the government was unable to arrest the deterioration of the Yemeni rial in government-controlled areas until early December, when Hadi appointed new leadership to the government-aligned Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (see: ‘Dramatic Exchange Rate Depreciation in Govt-Held Areas’).

Saeed’s return exacerbated the tension between himself and Hadi, who opposed the move.[11] Saeed’s relationship with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, the STC and other factions that have become increasingly hostile to Hadi’s leadership (and to the marginalized Islah party that he favors) has given the prime minister more room to maneuver and pursue his own agenda. This has put Saeed, a technocrat appointed in 2018 to fix the economy and rebuild state institutions, at loggerheads with Hadi’s sons, Nasser and Jalal, and others in the president’s Riyadh-based entourage. As Saeed’s power has grown, so has his conflict with Hadi. The extent of the rift was perhaps best illustrated by the prime minister’s decision in late December to monopolize the import and distribution of fuel products through the state-owned Yemen Petroleum Company.[12] This directly impacted Hadi’s inner circle, including billionaire businessman Ahmad al-Essi, who has derived significant wealth from the existing fuel import system.

Status Update: The Riyadh AgreementNascent hopes that the unity cabinet would implement the remaining political, economic, military and security requirements of the Riyadh Agreement have been dashed by infighting. Originally signed in November 2019, the Saudi-brokered deal for the government and STC to share power was agreed following the STC’s August 2019 takeover of Aden and the spread of fighting into Abyan and Shabwa governorates. The agreement contains 20 provisions settling differences between the government and STC, with the intention of allowing the two nominal allies to refocus on fighting Houthi forces.[13] The most notable accomplishments of the agreement include:

But important provisions remain unfulfilled:

Steps to further implement the Riyadh Agreement have proven short-lived, partial and open to reversal. Although the government’s 1st Presidential Protection Brigade entered Aden to take up positions on Sirah Island in late January, the redeployment of STC forces away from Aden and Abyan and government forces from Abyan and Shabwa did not occur. Nor were STC-aligned forces incorporated into state military and security structures.[14] As a result, the STC has retained effective control of Aden, emboldening the party to unilaterally institute changes strengthening its influence within state institutions (see: ‘The Push for Control of State Institutions’). Saudi Arabia invited the STC and Yemeni government to implementation talks in Riyadh on May 29, but hours before talks were to begin, fresh controversy erupted over the appointment of Major General Shallal Ali Shayea, the controversial STC-aligned ex-security director for Aden, as commander of the Counter-Terrorism Force.[15] A face-to-face session was postponed until June 14, then abruptly broken off by the STC.[16] Although Saudi Arabia has periodically called for implementation of the Riyadh Agreement, and both the government and STC remain publicly committed to it, no significant progress was made until the last week of 2021, when President Hadi appointed a new governor for Shabwa governorate under coalition pressure (see: ‘The Shabwa Protest Movement and Bin Adio’s Fall’).[17] |

STC Struggles with Balancing Act

The Southern Transitional Council attempted to pull off a risky balancing act in 2021, potentially alienating both its secessionist base and the international powers backing the government it had fought successfully to join. Its leader, Aiderous al-Zubaidi, had been based in the UAE since 2019. Bolstered by his return to Aden in May, the STC tried to negotiate the dual role it took on when joining the unity cabinet. Officially part of the government, it was now partnered with President Hadi and the very state from which it advocates secession, yet it still presents itself as an opposition movement that advocates for the southern people. The STC has to present different attributes to different audiences: if it is too radical it will alienate Saudi Arabia and the international community and risk being left out of future peace talks, if it is too pliant it will lose domestic support and legitimacy. This balancing act has led to contradictory messaging. In May, Al-Zubaidi called for the government to return to Aden. In the same speech, he called the government’s presence in Sayoun, Shabwa and Al-Mahra an “occupation”.[18]

The STC’s efforts to present itself as a viable alternative have been undermined by its inability to improve the economic and security situation in the south, where it operates both as a local administration and as part of the government. This dual role has cast the STC as responsible for both its own failures and those of the government in which it now participates. Deteriorating living conditions in southern Yemen have led to protests throughout the year. Despite attempts by the STC to co-opt the demonstrations, popular dissatisfaction was directed at the political elite of which they are now part. It is now much less tenable for the STC to cast blame elsewhere for any deterioration of law and order and the worsening economic conditions.

The party has attempted to strengthen the power of local authorities in Aden, as these report to the governor, former STC Secretary-General Ahmed Lamlas. However, this is a delicate process: the STC does not wish to antagonize Saudi Arabia or the international community by overly undermining the government. The party has also sought to expand its reach. In Hadramawt and Al-Mahra, the STC has allied with the tribal leaders and local political elites of the Inclusive Hadramawt Conference,[19] and with Abdullah Issa bin Afrar, head of the Council of the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra.[20] In Shabwa, the new governor (see: ‘Islah: In Search of Allies’) and the arrival of the UAE-backed Giants Brigades has allowed the pro-STC Shabwani Elite forces to return to the governorate (see: ‘Shabwani Elite Forces, Sabotage and Suppression’).

The STC has sought to strengthen its position as the representative of Yemen’s south, but the group’s difficult 2021 has impacted its popularity, especially among those who had been sympathetic to the party, though not outright supporters. But the STC is still seen as the only force able to protect the south against the Houthis, and anti-Islah southerners worry about the return of Islah should the STC fail. While the STC found it difficult to present itself as an alternative political authority in 2021, it successfully portrayed itself as the defender of the south, and this is the foundation of its strength.

The Push for Control of State Institutions

Infighting between factions associated with President Hadi and the STC over control of state institutions has continued since the government’s return to Aden. Contentious negotiations in 2020 resulted in STC Secretary-General Ahmad Hamad Lamlas’ appointment as Aden’s governor in July 2020 and Mutaher al-Shuaibi as security director in December 2020. However, multiple disputes erupted over appointments and the seizure of government buildings throughout 2021. On January 15, Hadi appointed several government officials without consulting with the STC leadership — most importantly former Prime Minister Ahmad bin Dagher as Shura Council speaker and Ahmad Ahmad Saleh al-Musay as attorney general.[21] The STC rejected the appointments as a unilateral “departure from what was agreed upon” and a “blow to the Riyadh Agreement.”[22] The Yemeni Socialist Party and Nasserist Unionist People’s Organization, both represented in the unity cabinet, also criticized the appointments, describing them as a “flagrant violation of the constitution… and the law of the judiciary.”[23] Despite these criticisms, and STC threats to retaliate, Bin Dagher and other Shura Council officials were sworn in before President Hadi on January 19.[24]

The response came on February 3, when the STC-affiliated Southern Judges Club, an association of judiciary members from southern governorates, issued a statement ordering the suspension of all judicial work until the Supreme Judicial Council was dismissed and restructured. The Judges Club said it was responding to the Judicial Council’s support for Al-Musay’s “illegal” appointment as attorney general.[25] On February 7, STC-aligned security forces began enforcing the decision, preventing judges and other employees from entering the Aden Judicial Complex in Khormaksar district.[26] Tensions escalated again in early July, when the president of the government-aligned Supreme Court, Judge Hamud al-Hitar, ordered the reopening of courts and referred Southern Judges Club leaders for investigation, while in response the Southern Judges Club announced it would begin managing judicial affairs in southern governorates.[27] In mid-August, the Judges Club announced the formation of a new body to manage judicial affairs and lifted its suspension on judicial work, although it continued to deny the legitimacy of Al-Musay’s appointment.[28]

Takeover of State Media

STC-aligned officials quickly used their new, formalized standing in Aden to impose their authority on news outlets in the interim capital. The struggle over media began in early May 2021, shortly after STC President Aiderous al-Zubaidi returned to the city.[29] On May 2, local authorities under the control of Lamlas issued a circular demanding all private media, broadcasting and production companies obtain licenses from the Aden Media Office, and warned that those failing to comply within two weeks would be subject to “administrative and legal measures” and fined.[30] Hadi’s information minister, Muammar al-Iryani, ordered local ministry offices not to comply with the circular, maintaining that media licensing was under his remit. STC-aligned authorities responded on May 20 with a requirement that journalists also register with the Aden Media Office.[31]

The dispute escalated in mid-June, coinciding with the start of renewed negotiations in Saudi Arabia over outstanding provisions of the Riyadh Agreement.[32] STC-aligned forces, reportedly acting on orders of Al-Zubaidi, took control of the headquarters of the Saba state news agency in Aden, expelling its employees.[33] In the following days, additional raids on Saba and the headquarters of the government-owned Thawra newspaper were reported,[34] and over objections from information minister Al-Iryani and the Yemeni Journalists Syndicate, the locations were seized and not returned.[35] On June 13, the STC announced the Saba headquarters as the new home of the Aden News Agency, framed as a resurrection of South Yemen’s pre-1990 state news organization; two days later, the STC-aligned National Southern Media Authority announced its intention to consolidate control over state media outlets in southern Yemen.[36]

Raids on State Institutions and Contested Appointees

STC attempts to take control of state institutions in Aden continued in late June and early July, prompting Saudi Arabia to publicly intervene. On June 30, Lamlas appointed Brigadier General Anwar Ali Yahya al-Omari director of the Aden branch of the Yemen Economic Corporation (YEC).[37] The YEC refused to work under Al-Omari, prompting forces from the STC-aligned 4th Military Region to storm the YEC’s main offices in Aden on July 4.[38] Similar disputes regarding security sector appointments resulted in protests and deadly clashes in Lawdar, Abyan governorate (see: ‘The Fight for Administrative Control’).

On July 2, Saudi Arabia issued a rare public statement criticizing the STC’s “political and media escalation,” calling the group’s appointments inconsistent with the Riyadh Agreement.[39] The government welcomed the intervention, and the STC responded with a statement reiterating its commitment to implementing the Riyadh Agreement “despite obstacles fabricated by the other party.”[40]

Despite the Saudi reprobation, the STC’s move on state institutions in Aden continued, with Lamlas appointing Saleh al-Jariri, an associate professor and head of the business administration department at the University of Aden, general manager of the Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) branch on July 8. The move prompted protests from the YPC union and a July 10 prime minister’s order canceling the appointment.[41] The issue reemerged in early November with Al-Jariri once again appointed by Lamlas to the post while President Hadi appointed former Water and Environment undersecretary Ammar al-Awlaqi as YPC executive director and Yaslam Saleh as head of the Aden Refinery Company.[42] The STC rejected the appointments as a unilateral decision in violation of the Riyadh Agreement, prompting Saudi Arabia to summon STC President Al-Zubaidi for consultations in Riyadh.[43]

Yemeni Parliament Fails to Reconvene

Following the return of the unity cabinet to Aden, there were growing calls for the return of the government-aligned parliament to resume its work. Theoretically composed of 301 seats, the House of Representatives last held elections in 2003; MP deaths and by-elections in the interim have left it with just 273 members. Like most state institutions, Yemen’s parliament fragmented following the events of 2014-2015, with the Houthi movement and government each claiming its support. While Houthi-aligned parliamentarians meet regularly in Sana’a, the government-aligned parliament last convened in Sayoun in April 2019. 118 MPs attended, 20 short of the quorum required by Yemen’s constitution.[44]

Attempts to reconvene the parliament to approve of the new unity cabinet’s agenda failed in early 2021. The issue resurfaced in May, when the leadership of the House of Representatives announced plans to reconvene parliament following the Eid al-Adha holiday in July.[45] On July 27, House Speaker Sultan al-Barakani arrived in Sayoun to prepare for a new session.[46] However, the STC refused to allow a parliamentary gathering to be held in Hadramawt governorate and demanded the government return to Aden.[47] Although the parliamentary leadership convened on July 28, no larger sessions had been held by year’s end.

Declining Currency, Living Standards Spur Unrest

Driven by electricity outages, rising food and fuel prices and a continued depreciation of the Yemeni rial, protesters took to the streets in waves throughout 2021 to demand action from the Hadi government, the STC and the Saudi-led coalition (see: ‘Dramatic Exchange Rate Depreciation in Govt-Held Areas’). Demonstrations began on March 2 near the Central Bank in Aden, where protesters demanded the payment of salaries for the military and security services. They were soon joined by others demanding the government address fuel shortages and electricity outages. Similar protests quickly spread to Abyan, Lahj and Hadramawt governorates.[48]

The protests reached a crescendo in mid-March. Government-aligned security forces in Sayoun fired on demonstrators on March 15. The next day protesters backed by the STC stormed the seat of government in Aden’s Ma’ashiq Palace, forcing local officials to flee.[49] On March 30, security forces in Mayfa’a, west of Mukalla city in Hadramawt governorate, again fired on demonstrators, killing one and injuring several others. Hadramawt Governor Faraj al-Bahsani promptly declared a state of emergency, justifying it as a COVID-19 protection measure (see: ‘Hadramawt Unrest’).[50] The same day, Saudi Arabia announced it would grant US$422 million worth of petroleum products to the Yemeni government for use in power stations and to support public services.[51]

The STC came out in support of the protests in Aden in March.[52] But political support was not always so forthcoming, and the STC and other parties cracked down on demonstrations throughout the year. Protestors’ demands ranged from resolving economic concerns to removing senior political officials.[53] Local media often emphasized the spontaneous, grassroots nature of the protests, and many demonstrators said they held all of the major parties responsible for not addressing the needs of the population.[54]

Another wave of protests broke out with the approach of summer. In late May, hundreds of people gathered outside the headquarters of the Saudi-led coalition in the Buraiqa district of Aden for days of protests calling for better services and economic conditions. In Taiz city, hundreds more called for the replacement of Taiz Governor Nabil Shamsan and other local officials accused of corruption, amid rising electricity prices and service outages.[55] Protests broke out again in Taiz in August and September, part of the strongest, most widespread and sustained demonstrations of 2021, which came during a precipitous drop in the Yemeni rial’s value in government-held territories. Thousands gathered to protest deteriorating economic and security conditions in the city, which is controlled by rival militias, and to demand the dismissal of corrupt officials, this time including the prime minister.[56]

Demonstrations erupted again across southern Yemen in mid-September, in Aden, Lahj, Abyan, Shabwa and Hadramawt. Authorities cracked down, and three protesters were killed in Aden and Mukalla on September 15.[57] Later that day, STC President Al-Zubaidi declared a state of emergency in Aden.[58] Despite the state of emergency, intermittent protests were reported in Aden and other government-held areas through the rest of the year.[59]

The Government-STC Conflict in Shabwa

Shabwa governorate, located in central-southern Yemen, lies at the nexus of the government-STC conflict over primacy in the south and the coalition-Houthi conflict for control of the country. Its strategic position and oil wealth mean that developments in Shabwa have the potential to disproportionately affect the broader war and any final settlement. Its central importance has intensified the political contestation between the Islah-aligned local authorities and an STC-supported protest movement, and made Islah’s loss of the governorship at the end of 2021 an especially strong blow to the party.

Shabwa emerged as a fulcrum of the conflict in 2019. In August, STC forces took control of Aden and began advancing east, seeking to bring all of southern Yemen under their control. After advancing quickly through Abyan, the STC was stopped in Shabwa by government-aligned forces and pushed all the way back to the gates of Aden. Following the government victory in Shabwa, the UAE-backed, STC-aligned Shabwani Elite forces largely demobilized, with many fighters returning to their homes. For Governor Mohammad Saleh bin Adio, a Shabwa native of the Laqmoush tribe and a leader in the Islah party, it was a significant success against not just the STC but also Islah’s regional nemesis, the UAE.[60]

Shabwa under Bin Adio, like Marib under Governor Sultan al-Aradah, had been touted as a bastion of relative peace and development in Yemen. The local authorities’ revenue sharing agreement with the government on oil production helped fund services and development projects, providing a degree of financial support most other governorates lacked.[61] However, this narrative of effective administration was fiercely disputed by the STC and its supporters, who characterized the rule of local authorities under Bin Adio as corrupt, oppressive and ineffective at stopping Houthi incursions.[62]

Qana Port Controversy

These competing narratives diverged prominently over the Qana port project on the governorate’s southern coast, which reportedly received its first shipment of diesel on January 10.[63] Qana was a centerpiece of Islah’s development rhetoric, with the project presented as giving government-aligned authorities an independent port, something they lacked given the STC’s control of the port of Aden, the substantial influence of the UAE and STC over the commercial port city of Mukalla[64] and Houthi control of the ports at Hudaydah, Ras Issa and Salif.[65] In a well-publicized ceremony, Bin Adio inaugurated the first phase of the Qana port’s construction on January 13, stating it would first be used to import fuel and later expanded to other types of commercial goods.[66]

The project quickly became a source of tension. STC-aligned ministers in the unity cabinet reportedly attempted to prevent ships from arriving at the port, alleging it was not properly supervised by the government, but only by the Islah-aligned local authorities.[67] Pro-STC media outlets accused local authorities of attempting to use the port to illegally smuggle in oil and weapons.[68] With the port only semi-operative, in April local authorities canceled the construction contract with the QZY company, owned by Yemeni billionaire and Hadi ally Ahmad al-Essi. Officials interviewed by the pro-Islah outlet Al-Masdar Online cited QZY’s apparent lack of seriousness in completing construction as well as “numerous violations” as reasons for terminating the contract.[69] However, Marib Press, quoting what it said was an official source at QZY, reported that the company had been doing extensive preparation and infrastructure work for upcoming stages of construction. The official said QZY had objected to a “special percentage” demanded by local authorities outside the terms of the agreement, suggesting had been the reason for its termination.[70] The QZY official said only one fuel shipment had been received since work began at the port, though the extent of other traffic wasn’t clear. The dispute, and the lack of transparency surrounding operations at the port, fed into the popular protests against Bin Adio and other Islah-aligned officials.[71]

The Shabwa Protest Movement and Bin Adio’s Fall

Throughout 2021, Shabwa was the site of an increasingly active STC-supported protest movement against the Islah-aligned authorities. The controversy over the Qana port and deteriorating economic conditions contributed to the unrest, as did military factors, including tension between Islah-aligned and UAE-backed forces at Balhaf and Al-Alam camp and the Houthi incursion into Shabwa (see: ‘The Conflict in Shabwa’). Multiple clashes erupted between security forces and protesters. Local authorities claimed they were preventing STC-supported militants from fomenting instability in the governorate, while protestors alleged the government was suppressing peaceful demonstrations.[72]

The protests intensified from September, when Houthi forces took control of the Bayhan, Ain and Usaylan districts in northwest Shabwa as part of their offensive in Marib (see: ‘The Road to Marib City’). Pro-STC media framed the losses as the result of Islah sidelining qualified military commanders in favor of party loyalists, or even as part of a secret pact with the Houthis.[73] Although protests were reported across southern and western Shabwa, the Nissab district emerged as a focal point following the October return of Sheikh Awadh bin al-Wazir al-Awlaqi, a GPC member of parliament and adviser to President Hadi who had been living in the UAE.[74] Al-Awlaqi held multiple protests calling for the removal of the Islah-aligned authorities, including a large gathering that drew people from across Shabwa on November 16.[75] Although the STC supported these protests and stood to benefit from Bin Adio’s ouster, it is worth noting that Al-Awlaqi did not explicitly express support for the STC. Rather, he condemned the local authorities and emphasized the need to unite all Shabwanis against the external threat of Houthi invasion.

The protests continued through December, as did the redeployment of UAE-backed forces from south of Hudaydah city, with the latter’s shift to engage Houthi forces in Shabwa coming after Riyadh agreed to an Emirati condition that Bin Adio be replaced. In late December, President Hadi obliged his Saudi patrons and dismissed Bin Adio as governor and appointed Al-Awlaqi. Although Hadi publicly offered Bin Adio a position as a presidential adviser — a recurring gesture to ousted allies — Bin Adio turned it down.[76] Within a week, Al-Awlaqi began releasing protestors and detainees, including pro-STC figures and members of the UAE-backed Shabwani Elite forces. This group was reconstituted in January 2022 as the Shabwa Defense Forces and assumed control of positions throughout the governorate, while the Giants Brigades launched an offensive into Bayhan and Marib (see: ‘The Conflict in Shabwa’).[77] Analysts considered this development as a major blow to the increasingly marginalized Islah party and a win for the newly assertive UAE. The STC, meanwhile, welcomed the appointment of Al-Awlaqi as governor.[78]

Islah: In Search of Allies

While ostensibly a political party, Islah’s difficult year stemmed largely from events on the battlefield. Government military units aligned with the Islamist movement performed poorly against the Houthis, most importantly in Marib but also in Taiz and Shabwa governorates (see: ‘Failed Government Offensives‘ and ‘The Bayhan Offensive and Its Aftermath’). Islah’s supporters blamed its military difficulties on weak support from the Saudi-led coalition and the outright demonization of the party by the UAE, STC and government-allied National Resistance Forces (NRF) led by Tareq Saleh, nephew of late President Ali Abdullah Saleh. This was especially the case in Shabwa, where Islah’s rapid retreat from three northwestern districts prompted accusations it was in league with the Houthis (see: ‘The Conflict in Shabwa’).[79] Military failures, combined with corruption allegations and economic protests, eased the way for the eventual sacking and replacement of Islah Governor Bin Adio. Divisions within the party were kept in check through the year, but early signs that members may be hedging their bets emerged as Islah’s political and military influence declined.

Marib city and government-controlled rural areas in the governorate remain a bastion of power for Islah, whose members dominate the local administration and security forces. However, the Houthi advance on Marib in late 2021 (see: ‘The Road to Marib City’) cost Islah both territory and tribal support. In Taiz, a March offensive by Islah-aligned forces ultimately failed to gain much territory, and throughout the year coalition efforts were complicated by self-interest and a lack of trust between the parties (see: ‘The Taiz Front’).

The divisions within the party itself are not overt. The old guard, such as party chairman Mohammed al-Yadoumi and its secretary-general Abdulwahab al-Ansi, consider the relationship with Saudi Arabia – where they both reside – important and a form of protection for Islah.[80] The Saudis themselves, while unwilling to fully trust Islah, understand that continued support for the group prevents it from becoming an out-and-out Qatari proxy. However, the younger generation of leaders, such as MP Hameed al-Ahmar, or Hamoud al-Mikhlafi, former head of the anti-Houthi resistance in Taiz, are closer to Qatar, and Qatari funding for media organizations and unofficial militia training camps is funneled through them. Doha’s interest in these training camps, and in Islah more generally, stems from a desire to have a local proxy that can be mobilized, if necessary, to influence events in line with its objectives.[81]

For now, it seems the Islah party is tied to President Hadi. Hadi represents the continued legitimacy of the Yemeni government of which Islah is part. Islah is important to Hadi too, as the party can be relied upon to provide a large number of fighters and political support. Islah, however, appears to be considering its options. In December, rumors of meetings between Islahi figures and the Houthis were confirmed when a Houthi leader shared pictures of a meeting with Fathi al-Azab, a leading member of Islah who had previously been imprisoned by the Houthis.[82] While a deal between the Houthis and Islah may seem far-fetched, the party appears to be considering its next steps in light of the increased strength of UAE-backed forces, such as the Giants Brigades and Tareq Saleh’s NRF. Both Saleh and the STC have an interest in weakening Islah. The importance of Marib to this dynamic cannot be overstated; if Islah finds itself losing control of the governorate to UAE-backed forces, it may grow fearful of being targeted itself, paving the way for a potential deal with the Houthis.

Saleh’s Forces Enter the Political Fray

To the south of Hudaydah city, Yemen’s west coast was technically under government control throughout the first 11 months of the year. In reality, this area along the Red Sea was held by the UAE-backed Joint Forces, an umbrella group consisting of several distinct militias originally formed for the 2018 coalition offensive against Hudaydah city. At least publicly, the Joint Forces has claimed since its inception that it is an apolitical organization dedicated to defeating the Houthi movement. That began to change in 2021.

On March 25, the National Resistance Forces, one of the Joint Forces groups backed by Abu Dhabi, announced the formation of a political bureau in Mokha. The move appeared to signal the NRF’s growing political ambitions, specifically those of its leader, Tareq Saleh.[83] Explaining the rationale for the political bureau, Saleh stressed that it was formed to provide a political entity to represent the West Coast in negotiations. He said it was not meant to replace the General People’s Congress (GPC), Yemen’s former ruling party, of which he remains a member. But in recent years the GPC has fragmented into several different factions.[84]

Following the founding of the political bureau, the NRF engaged in diplomatic and political activities. Saleh led an NRF delegation to Russia in June, with news outlets claiming he had unsuccessfully petitioned Moscow to help lift UN sanctions against his cousin, Ali Ahmad Saleh.[85] The late president’s eldest son has been in exile in the UAE, living under semi-house arrest since 2015. The NRF also publicly welcomed the appointment of new UN Special Envoy Hans Grundberg in August.[86] Tareq Saleh met with Grundberg in Mokha on November 11 during the latter’s tour of Taiz governorate, just days before the Joint Forces unexpectedly withdrew from Hudaydah city (see: ‘The Hudaydah Front’).[87] The UN said later that it had been given no prior notice of the withdrawal. The NRF has publicly expressed solidarity with both the Yemeni government and the STC, and has called for a united front against Houthi forces.[88]

While Saleh and the NRF have cast themselves as representing the West Coast, this claim has not gone undisputed. In recent years, Saleh has attempted to marginalize the local Tihama Resistance movement to consolidate his position, resulting in ongoing demonstrations.[89] In January 2021, tensions boiled over into armed conflict, with the NRF and Tihama Resistance fighting in Mokha, killing two.[90] Although no further clashes were reported in 2021, tensions resurfaced following the Joint Forces’ withdrawal from Hudaydah in November, which effectively ceded most of southern Hudaydah governorate to Houthi forces. The Tihama Resistance denounced the withdrawal as “vague and unjustified” given its detrimental effect on the local civilian population.[91] Forces aligned with Saleh have also clashed with Zayd al-Kharj, a notable tribal sheikh and merchant in Mokha with a significant share of the smuggling operations on the west coast.[92] In April, they reportedly stormed Kharj’s house and abducted his brother after Kharj prevented Saleh from holding an event to announce the establishment of a local NRF political bureau.[93]

Eastern Power Struggles: Al-Mahra, Socotra and Hadramawt

Power struggles among the internationally recognized government, the STC and local groups were apparent in Yemen’s easternmost governorates throughout 2021. Early in the year, the Hadrami Tribal Alliance called on President Hadi to create a “Hadramawt region”, which would include the governorates of Hadramawt, Shabwa, Al-Mahra and the Socotra archipelago.[94] The request echoed the federal system envisioned by the National Dialogue Conference, which concluded in 2014 under Hadi’s leadership. However, the STC has rejected calls for a federal, unified state structure, seeking instead to establish an independent southern state similar to the former People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) that would include these governorates.[95]

Socotra became a particular flashpoint following the STC’s seizure of the archipelago in the summer of 2020. On March 28, STC forces arrested protesters affiliated with the Peaceful Sit-In Committee of the Archipelago of Socotra, which opposes the Saudi-led coalition and the UAE-backed STC in particular.[96] On May 15, STC forces arrested prominent Socotri tribal sheikh Ali Suleiman Mohammed bin Malek after he called for protests against Emirati and Saudi interference on the archipelago.[97] The following month, STC forces in Socotra detained Yemeni activist Abdullah Bidahen for four days after he criticized Emirati influence over the group on Facebook.[98]

On June 8, prominent Mahri businessman and politician Abdullah Issa bin al-Afrar announced plans to launch a ferry service between Al-Mahra, Hadramawt and Socotra. Al-Afrar, son of the last leader of the former Sultanate of Al-Mahra and Socotra, which was annexed by the PDRY in 1967, purchased a 40-meter ferry ship with the help of late Omani leader Sultan Qaboos bin Said. Over the past decade, Al-Afrar has carefully navigated competing political interests in Al-Mahra and Socotra, with the aim of boosting his stature and perhaps establishing an autonomous region within the borders of the sultanate his family had ruled since the 16th century (see: ‘Dueling Mahri Scions Reveal Gulf Competition in Eastern Yemen’).

On November 2, Omani Economic Minister Said Mohammed al-Saqri called for the revival of plans to build an oil and gas pipeline linking Saudi oil fields to an export terminal on Oman’s southern coast on the Arabian Sea.[99] Anti-Saudi protest groups in Al-Mahra, formed following the deployment of Saudi forces to the governorate and aligned with Muscat, have strongly opposed rumored plans to construct a similar pipeline through their governorate. (see: ‘Has Riyadh Woken Up From Its Al-Mahra Pipe Dream?’).

Hadramawt Unrest